Breaking the Barrier: Advanced Strategies to Overcome Catalytic Scaling Relationships for Enhanced Efficiency

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of scaling relationships, a fundamental limitation in heterogeneous catalysis where the binding energies of reaction intermediates are linearly correlated, capping catalytic performance.

Breaking the Barrier: Advanced Strategies to Overcome Catalytic Scaling Relationships for Enhanced Efficiency

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of scaling relationships, a fundamental limitation in heterogeneous catalysis where the binding energies of reaction intermediates are linearly correlated, capping catalytic performance. Tailored for researchers and scientists, we explore the theoretical foundations of these relationships, detail innovative strategies to circumvent them—including dynamic site regulation and dual-site mechanisms—and discuss experimental validation through operando techniques. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with cutting-edge methodological advances, this review serves as a critical resource for the rational design of next-generation high-efficiency catalysts, with profound implications for energy conversion and sustainable chemical processes.

The Scaling Relationship Dilemma: Foundations, Origins, and Catalytic Limitations

Defining Linear Scaling Relationships (LSRs) in Catalysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are Linear Scaling Relationships (LSRs) in catalysis? Linear Scaling Relationships (LSRs) are observed correlations where the adsorption energies of different reaction intermediates on a catalyst surface are linearly related [1]. This means that the binding strength of one intermediate (e.g., *OH) can predict the binding strength of another (e.g., *OOH). These relationships arise because the adsorption energies of chemically similar intermediates (like *OH, *O, and *OOH in the oxygen evolution reaction) are correlated and often cannot be adjusted independently on a single active site [1].

2. Why are LSRs a fundamental limitation in catalytic design? LSRs impose an intrinsic limitation on a catalyst's maximal achievable performance and/or selectivity [1]. In multi-step reactions, it becomes thermodynamically challenging to optimally adjust the adsorption energy for every intermediate simultaneously. A catalyst that binds one intermediate strongly will often bind another too weakly, creating a compromise that limits the overall catalytic activity. This is often visualized on a theoretical overpotential volcano plot, where the summit represents the best possible activity under these constraints.

3. What strategies exist to overcome LSRs? Conventional strategies involve engineering heterogeneity into the catalyst to selectively stabilize certain intermediates over others. This can be done by confining intermediates within nanoscopic channels or creating multifunctional surfaces and interfacial sites [1]. An emerging, unconventional paradigm is the dynamic structural regulation of active sites [1]. This approach involves active sites that change their coordination and electronic structure during the catalytic cycle, thereby modulating adsorption energies for different intermediates independently and circumventing the static limitations of LSRs.

4. Can you provide a real-world example of breaking LSRs? A 2025 study demonstrated the breaking of LSRs in the electrochemical oxygen evolution reaction (OER) using a model Ni-Fe₂ molecular catalyst [1]. During the catalytic cycle, dynamic evolution of the Ni-adsorbate coordination, driven by intramolecular proton transfer, altered the electronic structure of the adjacent Fe active center. This dynamic dual-site cooperation simultaneously lowered the free energy change for O–H bond cleavage and O–O bond formation, thereby disrupting the inherent scaling relationship [1].

5. What experimental techniques are used to study LSRs and dynamic sites? Studying dynamic sites requires advanced operando or in situ techniques that can probe the catalyst under working conditions. Key methodologies include:

- Operando X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (XAFS): Used to verify local structural transformations and coordination environments of metal atoms during electrochemical activation and reaction [1].

- Electrokinetic Studies: Analyze reaction kinetics to infer mechanistic pathways and rate-determining steps.

- Density Functional Theory (DFT) & Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD) Simulations: Computational methods used to model reaction pathways, free energy changes, and the dynamic evolution of active sites [1].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inconsistent catalytic performance when attempting to replicate dynamic catalyst systems.

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low activity and no redox shift in CV | Failed formation of the target molecular complex (e.g., Ni-Fe trimer). | Ensure precise control during in situ electrochemical activation. Verify the purity of the electrolyte (e.g., use Fe-free KOH) and the concentration of intentionally added metal ions (e.g., 1 ppm Fe) [1]. |

| Formation of nanoparticles instead of atomically dispersed sites. | Overly harsh synthesis or activation conditions. | Optimize thermal annealing temperature and atmosphere. Use a support with high defect density (e.g., holey graphene nanomesh) to anchor single atoms and prevent aggregation [1]. |

| Poor reproducibility of operando XAFS data. | Unstable catalyst structure or inconsistent electrochemical conditioning. | Standardize the activation protocol (e.g., using consistent CV cycles, anodic chronopotentiometry). Ensure the electrochemical cell for operando measurements is properly designed to maintain potential control and electrolyte flow. |

Experimental Protocol: Constructing a Dynamic Ni-Fe Molecular Catalyst

This protocol summarizes the methodology for constructing a dynamic Ni-Fe₂ OER catalyst, as reported in recent literature [1].

1. Synthesis of Ni Single-Atom Pre-catalyst (Ni-SAs@GNM)

- Material: Prepare a graphene oxide (GO) aqueous suspension.

- Assembly: Seal the GO suspension in a Ni vessel at 80°C to spontaneously assemble a 3D Ni(OH)₂/graphene hydrogel.

- Drying: Subject the hydrogel to freeze-drying to obtain an aerogel.

- Annealing: Thermally anneal the aerogel at 700°C under an Ar atmosphere. This step reduces Ni(OH)₂ and etches the graphene into a holey graphene nanomesh (GNM).

- Purification: Treat the product with acid to remove nanoparticles, yielding a sample of Ni single atoms trapped on GNM (Ni-SAs@GNM). Confirm the atomic dispersion using aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM.

2. In Situ Electrochemical Activation to Form Ni-Fe Complex

- Electrode Preparation: Load the Ni-SAs@GNM pre-catalyst onto a glassy carbon working electrode.

- Electrolyte Preparation: Use a purified Fe-free 1 M KOH electrolyte with a deliberate addition of a low concentration (e.g., 1 ppm) of Fe ions (present as Fe(OH)₄⁻ anions) [1].

- Activation Procedure: Perform electrochemical activation using Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), typically between 1.1 and 1.65 V vs. RHE. Alternatively, anodic chronopotentiometry or chronoamperometry can be employed. The electrical field drives Fe(OH)₄⁻ to anchor onto Ni sites, forming the active Ni-Fe molecular complex.

The following table summarizes key quantitative data related to the Ni-Fe catalyst system and LSRs.

Table 1: Key Experimental Parameters and Findings from a Study on Breaking LSRs [1]

| Parameter | Value / Description | Significance / Function |

|---|---|---|

| Fe ion concentration | 1 ppm in 1 M KOH | Deliberate addition to form the heteronuclear active site during electrochemical activation. |

| Ni content in pre-catalyst | 0.82 wt% (determined by ICP-OES) | Quantifies the loading of the single-atom pre-catalyst. |

| Specific surface area | 266.9 m² g⁻¹ (for Ni-SAs@GNM) | Indicates a mesoporous structure beneficial for mass transport. |

| Ni/Fe atomic ratio | ~5.2:1 (after activation) | Determined by SXRF and ICP-OES, confirming Fe incorporation. |

| Primary characterization | Operando XAFS, HAADF-STEM, Electrokinetics | Techniques used to identify dynamic structural change and mechanism. |

| Key mechanistic insight | Dynamic Ni-adsorbate coordination alters Fe site electronics | The proposed mechanism for simultaneously optimizing O-H cleavage and O-O formation, thereby breaking the LSR. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Their Functions for Dynamic Catalyst Studies

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Graphene Oxide (GO) suspension | Starting material for creating the 3D conductive support structure. |

| Ni Vessel | Serves as a source of Ni ions for the spontaneous formation of Ni(OH)₂ during hydrogel assembly. |

| Purified KOH electrolyte | Provides the alkaline reaction environment; purity is critical to avoid unintended metal contamination. |

| Fe salt (e.g., Fe(NO₃)₃) | Source of Fe ions added at ppm levels to the electrolyte for in situ active site formation. |

| Synchrotron Radiation Source | Enables high-resolution operando XAFS measurements to probe the local structure of atoms under reaction conditions. |

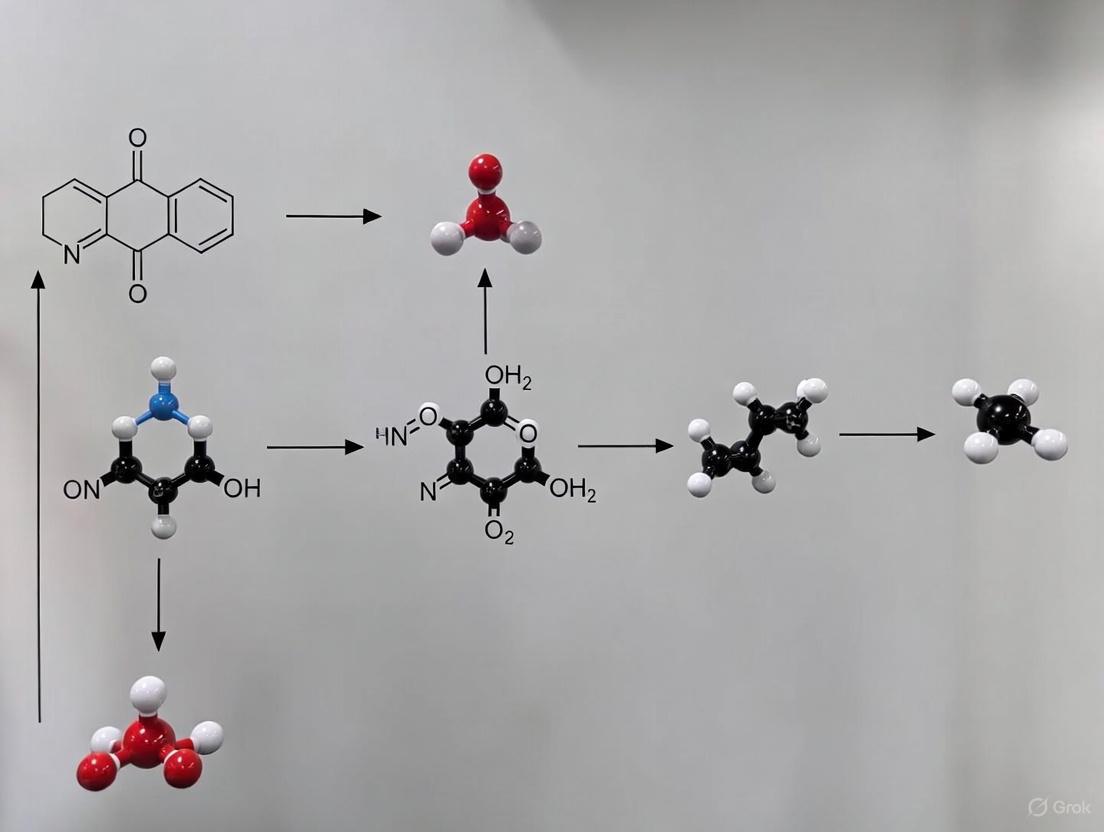

Conceptual Diagrams of LSRs and Breaking Strategies

LSR Limitation in OER

Dynamic Site Regulation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental principle of Bond Order Conservation (BOC) in catalysis?

Bond Order Conservation is a theoretical principle stating that the total bond order between a central atom and its ligands remains constant. When an adsorbate binds to a catalyst surface, the formation of new adsorbate-surface bonds occurs at the expense of the internal bond orders within the adsorbate itself. The sum of these bond orders is conserved. This principle is the foundational origin for the observed scaling relationships in heterogeneous catalysis, which linearly relate the adsorption energies of different reaction intermediates across various catalyst surfaces [2] [3] [4].

Q2: How do scaling relationships limit catalytic performance?

Scaling relationships create a fundamental limitation known as the "catalytic ceiling" or "volcano plot" relationship. Because the adsorption energies of different reaction intermediates are linearly correlated, it becomes impossible to independently optimize the binding strength for all intermediates involved in a reaction. Strengthening the binding of one intermediate inevitably strengthens the binding of others, often stabilizing rate-limiting transition states too much or destabilizing key intermediates. This interdependence places a maximum on the theoretical catalytic activity for a given class of materials, such as transition metals [5].

Q3: What strategies can be used to overcome the limitations of scaling relationships?

Advanced strategies focus on breaking the linear constraints imposed by simple scaling:

- Using BOC-derived Microkinetic Modeling: Applying BOC principles to calculate transition state energies and construct microkinetic models helps identify the specific reaction components that determine overall activity, as demonstrated for NH₃ decomposition [3].

- Designing Integrative Catalytic Pairs (ICPs): These feature spatially adjacent, electronically coupled dual active sites that function cooperatively yet independently. This functional differentiation allows for concerted reactions involving multiple intermediates, moving beyond the limitations of uniform active sites [6].

- Exploring Unconventional Catalytic Environments: Applying electromagnetic fields, using plasma catalysis, or leveraging plasmonic effects can alter the energy landscape and potentially circumvent the constraints of thermal catalysis scaling relationships [7].

Q4: How is the bond order quantified and used in practice?

The bond order parameters (( \lambdai )) for individual bonds are normalized (( \gammai = \lambdai / x{max} )) so that their sum is unity when the central atom satisfies its octet rule or reaches its maximum bond order [4]: [ \sum{i}^{K} \gammai = 1 ] Here, ( K ) is the number of bonds and ( x{max} ) is the maximum number of ligands. This formalism allows for the prediction of adsorption energies for intermediates (e.g., C₂Hₓ species) on different metals based on the adsorption energy of a central atom (e.g., carbon), with a valence parameter ( \gamma(x) = (x{max} - x)/x_{max} ) describing the slope of the scaling relation [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Predictive Accuracy of Scaling Models

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Predicted adsorption energies significantly deviate from experimental or DFT-calculated values. | Model is applied to adsorbates with complex internal bonding (e.g., multiple double/triple bonds) not accounted for in simple AHₓ schemes [4]. | Classify surfaces as "reactive" (π-bond destroying) or "noble" (π-bond preserving) and adjust the internal bond orders of the adsorbate accordingly before applying scaling relations [4]. |

| Model does not account for species-specific differences in key metabolizing enzymes, transporters, or protein binding between different test systems (common in allometric scaling for drug development) [8]. | Incorporate in vitro data (e.g., drug metabolism, plasma protein binding) using In Vitro/In Vivo Extrapolation (IVIVE) or move to more complex Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling [8]. | |

| Inconsistent transition state energy predictions. | Using linear fits to a set of calculated transition state energies can introduce error [3]. | Apply a BOC-based scheme that requires a limited set of input data to achieve lower errors in transition state energies as a function of simple descriptors [3]. |

Issue 2: Identifying and Modeling Beyond Linear Scaling Relationships

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst optimization hits a performance plateau predicted by a volcano plot. | The catalyst material class (e.g., pure transition metals) is constrained by inherent scaling relationships between key intermediates [5]. | Shift catalyst design strategy. Explore materials with different coordination environments, such as single-atom alloys, oxides, sulfides, or nitrides, which can alter adsorption sites and break simple linear scaling [6] [7]. |

| The catalyst shows poor selectivity in a complex reaction network. | Uniform active sites on single-atom catalysts or simple metals cannot optimally interact with multiple, different intermediates [6]. | Design Integrative Catalytic Pairs (ICPs) or dual-atom sites where spatially adjacent, electronically coupled active sites function cooperatively to handle different reaction steps independently [6]. |

Key Experimental & Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing a Scaling Relationship for Hydrocarbon Intermediates

This protocol is based on the methodology used to establish scaling relations for C₂Hₓ species on transition metal surfaces [4].

1. Objective: To determine the linear scaling relationship between the adsorption energies of various C₂Hₓ intermediates and the adsorption energy of a central carbon atom across multiple transition metal surfaces.

2. Methodology:

- Computational Setup: Perform Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations using a plane-wave basis set and ultrasoft pseudopotentials (e.g., with the RPBE functional). Use a plane-wave cut-off energy of 340 eV [4].

- Surface Models: Perform calculations on a representative set of transition metal surfaces, including close-packed surfaces (e.g., fcc(111), hcp(0001), bcc(110)) and stepped surfaces (e.g., fcc(211)) [4].

- Energy Calculations:

- Calculate the adsorption energy (( \Delta E_{M}^{A} )) of a carbon atom on each metal surface

M. - Calculate the adsorption energy (( \Delta E{M}^{AHx} )) for a series of C₂Hₓ intermediates (e.g., x = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6) on the same set of surfaces.

- Calculate the adsorption energy (( \Delta E_{M}^{A} )) of a carbon atom on each metal surface

- Data Analysis:

- For each intermediate C₂Hₓ, plot its adsorption energy on different metals against the adsorption energy of carbon on those same metals.

- Perform a linear regression for each intermediate. The slope of the line is the valence parameter, ( \gamma ).

- The relationship is given by: [ \Delta E{M2}^{AHx} = \Delta E{M1}^{AHx} + \gamma(x)(\Delta E{M2}^{A} - \Delta E{M1}^{A}) ] where ( \gamma(x) = (x{max} - x)/x{max} ), and ( x_{max} ) is the maximum number of hydrogen atoms needed to satisfy the octet rule for the atom forming the bond to the surface [4].

Protocol 2: Applying BOC to Microkinetic Modeling of a Reaction

This protocol outlines how to use BOC to model the kinetics of a catalytic reaction, such as ammonia decomposition [3].

1. Objective: To establish a microkinetic model for the formation of products (e.g., N₂ and H₂ from NH₃) to identify the reaction components that determine catalytic activity.

2. Methodology:

- Energetics Input: Use a BOC-based scheme to calculate the transition state energies and structures of reaction intermediates on a series of transition metal surfaces. This requires only a limited set of input data (e.g., atomic adsorption energies) and is more accurate than simple linear fits [3].

- Model Construction:

- Map the full reaction pathway, identifying all elementary steps (e.g., for NH₃ decomposition: successive dehydrogenation steps and N₂ recombination).

- Use the BOC-derived energies for intermediates and transition states as input parameters for the microkinetic model.

- Simulation & Analysis:

- Run the microkinetic model to simulate reaction rates and product distributions under various conditions (temperature, pressure).

- Analyze the model to identify the rate-determining steps and surface coverages that control the overall activity across different metals. This provides insight for rational catalyst design [3].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Scaling Relation Valence Parameters (γ) for Selected Intermediates

This table summarizes the valence parameter γ for different adsorbate types, which defines their scaling relationship with the atomic adsorbate according to the equation ( \Delta E{M}^{AHx} \propto \gamma \cdot \Delta E_{M}^{A} ) [4].

| Adsorbate Type | Example Intermediates | Valence Parameter (γ) | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogenated Atoms | CH₃, NH₂, OH | ( \gamma = (x{max} - x)/x{max} ) | The parameter x is the number of H atoms in the intermediate. x_max is 4 for C, 3 for N, and 2 for O [4]. |

| C₂ Species (on noble metals) | C₂Hₓ (with intact π-bonds) | Slope depends on preserved internal multiple bonds. | On noble metal surfaces, internal π-bonds of the hydrocarbon are not broken upon adsorption, affecting the slope [4]. |

| C₂ Species (on reactive metals) | C₂Hₓ (with destroyed π-bonds) | Slope depends on the saturation of the bonding carbon atom. | On reactive metals, the π-system is destroyed, and the scaling is determined by the saturation level of the carbon atom bonded to the surface [4]. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Catalysis Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) Codes (e.g., Dacapo, VASP) | Calculating adsorption energies, transition states, and electronic structures of catalyst surfaces [4]. |

| Transition Metal Surfaces (fcc, hcp, bcc) & Stepped Surfaces (e.g., fcc(211)) | Serving as model systems to study structure-sensitivity and establish scaling relationships across the periodic table [3] [4]. |

| Microkinetic Modeling Software (e.g., Python, MATLAB scripts) | Simulating the overall reaction rate and selectivity based on elementary step energetics to identify performance descriptors [3]. |

| Plasmonic Nanoparticles (e.g., Au, Ag) | Generating strong local electromagnetic fields and hot carriers to drive reactions via unconventional pathways [7]. |

Conceptual Diagrams

Diagram 1: BOC Principle and Scaling Relationship

BOC and Scaling Principle

This diagram illustrates the core principle. During adsorption, new surface bonds (blue) are formed, weakening the adsorbate's internal bonds (yellow). The Bond Order Conservation principle dictates that the total bond order is maintained. This leads to a linear scaling relationship (green-to-red gradient) where the adsorption energies of different intermediates on weak-binding metals predict their energies on strong-binding metals.

Diagram 2: Overcoming Scaling Limitations

Breaking the Scaling Limit

This workflow outlines the problem and solutions. Conventional single-site catalysts (top path) are constrained by linear scaling relationships, leading to performance plateaus. To overcome this, researchers can employ strategies (bottom path) such as designing Integrative Catalytic Pairs (ICPs) with dual sites or using unconventional catalytic environments, which can break the scaling constraints and enhance performance.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is a Linear Scaling Relationship (LSR) and how does it limit catalyst activity? In multi-step catalytic reactions like the oxygen evolution reaction (OER), the adsorption energies of different reactive intermediates (such as *OH, *O, and *OOH) are often linearly correlated on conventional single-site catalysts. These Linear Scaling Relationships (LSRs) create a fundamental constraint, making it impossible to independently and optimally adjust the adsorption strength of every intermediate to achieve the maximum theoretical activity [1].

2. How can a Volcano Plot visualize the limitations set by LSRs? A volcano plot is a scatterplot that visualizes the relationship between catalyst activity (often represented as the reaction rate or overpotential) and a descriptor variable (typically the adsorption energy of a key intermediate). The "volcano" shape arises because activity increases as the descriptor energy approaches an optimal value, and then decreases as the energy becomes too strong or too weak. The peak of the volcano represents the maximum activity achievable within the constraints of the LSRs [1].

3. Our experimental data shows points far from the volcano curve. What does this mean? Data points that lie significantly above the predicted volcano curve are highly significant. They indicate that your catalyst system may be successfully circumventing the classic LSRs. This is often achieved through advanced catalyst design strategies, such as creating dynamic active sites or dual-site cooperation, which allow for a more independent adjustment of intermediate binding energies [1].

4. What are the key considerations for creating a statistically sound volcano plot? The two most critical variables are the measure of activity (e.g., log of the turnover frequency) and the descriptor (e.g., adsorption energy). Ensure your statistical thresholds for significance (p-value) and magnitude of change (e.g., log2 fold change) are chosen appropriately for your specific dataset and research question. Incorrect thresholds can misrepresent the number and identity of significant "hits" [9].

5. What strategies exist to break LSRs and reach the top of the volcano? Recent research has demonstrated that LSRs are not absolute barriers. Successful strategies include:

- Dynamic Structural Regulation: Constructing catalysts where the active site dynamically changes its coordination during the catalytic cycle, thereby altering the electronic structure for different reaction steps [1].

- Dual-Site Cooperation: Employing adjacent metal centers that work in concert, where one site participates in the reaction to modulate the electronic structure of the other active site [1].

- Confinement Effects: Using nanoscopic channels or introducing proton acceptors to selectively stabilize certain intermediates over others [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No significant points on the volcano plot after Differential Gene Expression (DGE) analysis. | Overly stringent statistical thresholds (p-value or fold change). | Re-evaluate threshold choices based on your experimental system. Consider using adjusted p-values to control for false discoveries [9]. |

| Poor separation between significant and non-significant data points. | The chosen descriptor does not effectively correlate with activity for your catalyst system. | Explore alternative descriptor variables that may have a more fundamental relationship with the catalytic activity for your specific reaction. |

| Unexpected clustering of data points in a single region of the plot. | Underlying similarity in the electronic or geometric structure of the tested catalysts. | This can be a valuable finding, indicating a common limitation or shared property across your catalyst library that warrants further investigation. |

| Catalyst performance in experiments does not align with volcano plot predictions. | The assumed reaction mechanism (e.g., Adsorbate Evolution Mechanism) may not be operative. The catalyst may undergo surface reconstruction under operating conditions. | Perform operando characterization (e.g., XAFS) to identify the true active site and mechanism under reaction conditions [1]. |

Experimental Protocol: Generating a Volcano Plot from DGE Data

This protocol outlines the steps to create a basic volcano plot using R, based on differential gene expression results.

Step 1: Environment Setup and Data Import Load the necessary R libraries and import your dataset. The dataset should contain columns for gene identifiers, p-values, and log2 fold change values.

Step 2: Define Significance Thresholds Add a new column to classify each gene (or catalyst) based on your chosen thresholds for statistical significance and magnitude of effect.

Step 3: Construct the Basic Volcano Plot

Use ggplot2 to create the plot, adding threshold lines to guide interpretation.

Step 4: Customize and Export the Plot Refine the plot's appearance by setting a theme and adjusting visual elements. Finally, export the plot for publication.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Role in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Graphene Oxide (GO) Suspension | Serves as a precursor for creating a 3D conductive carbon support structure, facilitating the formation of hydrogels and aerogels [1]. |

| Ni Vessel / Ni Salt Precursor | The source of Nickel atoms. Used to construct single-atom pre-catalysts (e.g., Ni-SAs@GNM) which can be dynamically transformed into active sites [1]. |

| Fe Ion Solution (e.g., Fe(OH)₄⁻) | Introduced at ppm levels into the electrolyte for in situ electrochemical doping. Essential for forming heterobinuclear active sites (e.g., Ni-Fe complexes) [1]. |

| Purified KOH Electrolyte | Provides the alkaline reaction environment for OER. Must be purified to be Fe-free to control the incorporation of Fe ions and ensure experimental reproducibility [1]. |

| DGE Results File (.csv) | A comma-separated values file containing the essential data columns: gene/catalyst identifier, p-value, and log2 fold change, which serve as the direct input for volcano plot generation [9]. |

Conceptual Workflow: From Catalyst Design to Overcoming LSRs

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key concepts involved in moving from a traditional catalyst limited by LSRs to an advanced design that can circumvent these relationships.

In the quest for efficient energy conversion technologies, such as water electrolyzers and fuel cells, the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) and oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) are pivotal. These reactions are constrained by a fundamental catalytic principle: linear scaling relationships (LSRs). These are linear correlations between the adsorption energies of key oxygenated intermediates—*OH (hydroxyl), *O (oxygen), and *OOH (hydroperoxyl)—on catalyst surfaces. Because these intermediates are chemically similar, their adsorption strengths cannot be adjusted independently [10]. This inherent scaling imposes a thermodynamic overpotential, creating an "activity cliff" that limits the performance of even the most promising catalysts. This technical support article, framed within the broader thesis of overcoming these scaling relationships, provides a practical guide for researchers navigating the experimental challenges in OER and ORR catalyst development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are linear scaling relationships (LSRs) and why are they a problem for the Oxygen Evolution Reaction (OER)?

LSRs describe the linear correlations between the adsorption energies of different reaction intermediates on a catalyst surface. In the OER, which follows the Adsorbate Evolution Mechanism (AEM), the key intermediates are *OH, *O, and *OOH [11]. The problem arises because the adsorption energy of *OOH is almost always linearly correlated with the adsorption energy of *OH on conventional single-site catalysts [10] [11]. This correlation means that if a catalyst binds *OH optimally, it will bind *OOH too weakly, or vice-versa. This creates a fundamental thermodynamic limitation, preventing the simultaneous optimization of all reaction steps and capping the maximum achievable activity [11].

Q2: Is the *O vs. *OH scaling relation more important than the *OOH vs. *OH relation for OER trends?

Emerging research suggests that the scaling relation between *O and *OH has been largely overlooked but is critically important for understanding OER activity trends. While the *OOH vs. *OH relationship has been the primary focus in the literature, the *O vs. *OH relationship is equally significant for identifying material motifs and constructing accurate volcano plots to guide catalyst discovery [10]. A comprehensive descriptor approach should consider both relationships to effectively capture catalytic trends.

Q3: Why do my measured ORR activities on platinum show a strong dependence on the electrochemical scan rate?

This is a common experimental challenge rooted in the dynamic nature of the platinum surface. Common half-cell measurements using the rotating disk electrode (RDE) protocol deliver ORR activities that are intrinsically linked to the chosen scan rate. This is because the Pt surface is not static; surface oxygen species (*OH and *O) form and reduce as a function of potential and time. At different scan rates, the surface is in a different state of oxidation, which physically blocks active sites and electronically alters the binding energy of ORR intermediates. Therefore, the measured current is not purely kinetic but is convoluted with these surface processes, making the choice of scan rate somewhat arbitrary from a fundamental perspective [12].

Q4: What are the key strategies for breaking the scaling relationships in OER catalysis?

The most effective strategies involve moving beyond static, single-site catalysts. The primary approach is to engineer heterogeneity to selectively stabilize the *OOH intermediate over *OH. This can be achieved through:

- Dynamic Structural Regulation: Creating active sites that dynamically change their coordination during the catalytic cycle to modulate electronic structure [11].

- Dual-Site Cooperation: Employing multi-functional surfaces or interfaces where different sites cooperate to stabilize different intermediates [11].

- Confinement Effects: Using nanoscopic channels or pockets to confine intermediates.

- Introducing Proton Acceptors: Incorporating functional groups that can act as proton acceptors during the reaction [11].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent ORR kinetics on Pt | Scan rate dependency and undefined surface oxygen state [12]. | Use a deconvolution protocol to extract intrinsic kinetics from surface oxygen effects. Perform measurements at multiple scan rates and extrapolate. |

| Poor OER activity in base | Strong scaling relationships on a single-site catalyst [11]. | Develop bimetallic catalysts (e.g., Ni-Fe) that enable dynamic dual-site cooperation to circumvent LSRs. |

| Low reproducibility of catalyst performance from lab to scale | Variations in physicochemical properties (surface area, porosity) and heat/mass transfer issues during scale-up [13]. | Implement pilot-scale testing and advanced simulation/modeling. Design for scalability from the initial R&D phase [13]. |

| Fe impurity contamination in OER tests | Unintentional incorporation of Fe from electrolytes or apparatus, altering active sites [11]. | Use high-purity KOH electrolytes and ensure all glassware is meticulously cleaned. Control Fe addition for systematic study. |

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their functions for key experiments in oxygen electrocatalysis.

| Research Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Polycrystalline Pt Electrode / RDE | The model system for fundamental ORR studies, providing a well-defined and reproducible surface for kinetic analysis [12]. |

| Holey Graphene Nanomesh (GNM) | A support material for single-atom catalysts, offering high surface area and defect-rich sites for anchoring metal atoms [11]. |

| Ni-Fe Molecular Complex | A model bimetallic catalyst system constructed via in situ electrochemical activation, used to study dynamic site cooperation for breaking OER scaling relationships [11]. |

| High-Purity KOH Electrolyte | Essential for reliable OER testing in alkaline conditions, preventing false activity from trace metal impurities (e.g., Fe) [11]. |

| Three-Electrode Electrochemical Cell | The standard setup for half-cell measurements, consisting of a Working Electrode, Reference Electrode (e.g., RHE), and Counter Electrode (e.g., Pt wire) [14]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Extracting Intrinsic ORR Kinetics on Polycrystalline Platinum

Objective: To deconvolute the intrinsic ORR kinetics from the effects of surface oxygen on Pt(pc) [12].

Methodology:

- Electrode Preparation: Use a polished glassy carbon rotating disk electrode (RDE). Clean the Pt(pc) electrode through potential cycling in a deaerated supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M HClO₄ or H₂SO₄) within a defined potential window (e.g., 0.05 - 1.4 V vs. RHE) until a stable cyclic voltammogram (CV) is obtained [14].

- Surface Characterization: Record a CV at multiple scan rates (e.g., 20-100 mV/s) in the supporting electrolyte to characterize the hydrogen underpotential deposition (H-upd) and oxygen underpotential deposition (O-upd) regions. Use techniques like scanning potential electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (SPEIS) to separate the charge associated with reversible *OH formation from irreversible *O species [12].

- ORR Activity Measurement: Saturate the electrolyte with oxygen. Record ORR polarization curves using the RDE at a rotation speed of 1600 rpm (or similar) at multiple scan rates (e.g., 1-50 mV/s). Correct all data for background and mass transport contributions to obtain the kinetic current (i_kin) [12] [14].

- Data Deconvolution: Analyze the kinetic current as a function of potential and scan rate. The intrinsic ORR current on a metallic Pt surface can be extracted by accounting for the blocking and electronic effects of surface oxygen using an equation of the form [12]:

i_ORR(E) = T_Blocking * T_Electronic * i_kin(E)

Key Quantitative Data from Protocol: Table: Intrinsic ORR Kinetic Parameters for Pt(pc) [12]

| Parameter | Value | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Tafel Slope | ~120 mV/decade | Extracted intrinsic value |

| Exchange Current Density (i₀) | 13 ± 4 µA/cm² | |

| Specific Activity | 7 mA/cm² | at 900 mV vs. RHE |

| O-upd Charge | ||

| - Reversible *OH | 40 ± 5 µC/cm² | |

| - Total Irreversible *O | Dominates O-upd region |

Protocol: Constructing a Ni-Fe Molecular Complex for OER

Objective: To synthesize a dynamic dual-site OER catalyst via in situ electrochemical activation and study its mechanism [11].

Methodology:

- Pre-catalyst Synthesis: a. Synthesize a Ni single-atom pre-catalyst (Ni-SAs@GNM). Create a 3D Ni(OH)₂/graphene oxide hydrogel. b. Freeze-dry the hydrogel to form an aerogel. c. Thermally anneal the aerogel at 700°C under an inert atmosphere (Ar) to form a holey graphene nanomesh (GNM) with Ni/NiO nanoparticles. d. Remove nanoparticles via acid treatment, leaving atomically dispersed Ni single atoms anchored on the GNM support [11].

- Electrochemical Activation: a. Load the Ni-SAs@GNM onto a glassy carbon working electrode. b. Use a standard three-electrode setup in a Fe-free 1 M KOH electrolyte with a deliberate addition of a low concentration (e.g., 1 ppm) of Fe ions (Fe(OH)₄⁻). c. Perform activation using cyclic voltammetry (CV) between 1.1 and 1.65 V vs. RHE. This drives Fe species to anchor onto Ni sites, forming an O-bridged Ni-Fe₂ trimer molecular complex [11].

- Characterization: a. Use operando X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) to verify the formation of the Ni-Fe molecular complex and track structural changes during catalysis. b. Employ density functional theory (DFT) and ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations to understand the dynamic coordination evolution during the OER cycle [11].

Key Performance Metrics:

- The catalyst exhibits a notable intrinsic OER activity due to its ability to disrupt the conventional scaling relationships [11].

- The dynamic coordination of the Ni site with adsorbates (OH and H₂O) modulates the electronic structure of the adjacent Fe active site.

- This dual-site cooperation simultaneously lowers the free energy for O-H bond cleavage and *OOH formation, breaking the linear scaling relationship [11].

Signaling Pathways & Workflows

Diagram: Dynamic Catalyst Workflow for Breaking OER Scaling.

Diagram: OER/ORR Shared Constraint.

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental origin of the performance ceiling in single-site catalysts?

The performance ceiling in single-site catalysts arises from a fundamental constraint known as the adsorption-energy scaling relation [15] [16].

In electrocatalytic reactions like the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) or oxygen evolution reaction (OER), the reaction proceeds through multiple intermediates (e.g., *OOH, *O, and *OH). On a catalyst with only one type of active site, the adsorption-free energies of these different intermediates are strongly linearly correlated [15]. This means the binding strength of one intermediate dictates the binding strength of all others; you cannot independently optimize the adsorption energy for each reaction step [16]. This scaling relation creates an inherent thermodynamic overpotential, as the ideal balance of energies for all intermediates cannot be achieved on a single site, leading to sluggish reaction kinetics and a performance plateau [15].

FAQ 2: How can we experimentally diagnose the limitations imposed by scaling relations?

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful technique to probe kinetic limitations. However, traditional EIS requires equilibrium conditions, which may not reflect the catalyst's behavior during actual operation. Operando EIS, performed under real working conditions, provides more relevant insights into dynamic processes and resistances, such as charge transfer barriers linked to intermediate adsorption [17]. Furthermore, in situ synchrotron spectroscopy techniques, such as X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) and Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, can directly identify reaction intermediates and the electronic structure of active sites during catalysis [16]. For instance, the absence of a *OOH intermediate and the observation of a key M1–O–O–M2 intermediate can provide direct evidence for a reaction mechanism that circumvents the conventional scaling relation [16].

FAQ 3: What catalyst design strategies can break the scaling relation?

Advanced catalyst designs move beyond single-site models to break the scaling relation. Key strategies include:

| Strategy | Mechanism | Key Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Dual-Site Mechanisms [16] | Two adjacent but distinct metal atoms (e.g., Pt and Fe) adsorb an O₂ molecule in a "side-on" configuration (M1–O–O–M2), enabling direct O–O bond breakage without forming the *OOH intermediate. | In situ SR-FTIR identified the Pt–O–O–Fe intermediate; XAFS confirmed the atomic-scale structure of N-bridged Pt = N₂ = Fe sites [16]. |

| High-Entropy Alloys (HEAs) [18] | The complex local environments created by mixing multiple metal elements (e.g., Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu) creates a broad adsorption energy landscape, allowing different intermediates to be stabilized optimally on different local sites. | DFT calculations showed charge redistribution and a wide range of d-band center positions, enabling optimal adsorption for multiple NO₃RR intermediates [18]. |

| High-Density Single-Atom Catalysts [19] | Creating high loadings of stable single atoms on a support via atomic-scale self-rearrangement from metastable phases. The strong metal-support interaction can modulate electronic structure. | AC-HAADF-STEM images confirmed high-density Ir single atoms; Operando XAFS tracked charge redistribution and strong p-d-f orbital couplings during OER [19]. |

Experimental Protocol: Investigating a Dual-Site Catalyst

The following protocol outlines the synthesis and characterization of a N-bridged Pt=Fe atomic-scale bimetal assembly (ABA) designed to break the ORR scaling relation [16].

1. Synthesis of Amino-Functionalized Carbon Nanoflakes (CNF–NH₂)

- Method: Nitrate pyrene (C₁₆H₁₀) in hot HNO₃ to form trinitropyrene. Subsequently, replace the nitro groups (-NO₂) with amino groups (-NH₂) to obtain CNF–NH₂.

- Purpose: The amino groups serve as anchoring sites for metal ions.

2. Metal Precursor Chelation and Pyrolysis

- Method: Prepare a precursor solution of Fe³⁺ and [PtCl₆]²⁻ in glycol solvent. Mix this solution with the CNF–NH₂, allowing the metal cations to chelate with the -NH₂ groups during freeze-drying. Finally, pyrolyze the material in an inert atmosphere at 700°C.

- Purpose: The pyrolysis step forms the stable, nitrogen-bridged atomic-scale Pt=Fe structure.

3. Structural and Electronic Characterization

- Aberration-Corrected HAADF-STEM: Use this technique to confirm the atomic dispersion of Pt and Fe atoms and measure the intermetallic distance (typically ~2.8-2.9 Å is targeted for the dual-site mechanism).

- X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS): Perform XANES and EXAFS to determine the oxidation states of the metals and confirm the coordination environment (e.g., the absence of metal-metal bonds and presence of metal-nitrogen bonds).

4. In Situ Mechanistic Probe during ORR

- In Situ Synchrotron Radiation FTIR: Use this sensitive technique to monitor the formation (or absence) of reaction intermediates on the catalyst surface under operating conditions. The key observation is the detection of a Pt–O–O–Fe vibration and the absence of *OOH signals.

- Electrochemical Polarization Curves: Record linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves in an O₂-saturated electrolyte to evaluate ORR activity. Calculate the kinetic current density (Jₖ) at a specific potential (e.g., 0.95 V vs. RHE) to quantify performance gains.

5. Device Integration Test

- Method: Integrate the best-performing catalyst as an air cathode in a practical device, such as a zinc-air battery.

- Metrics: Measure the peak power density (e.g., mW cm⁻²) and cycling stability to assess real-world viability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Catalyst Research |

|---|---|

| Amino-Functionalized Carbon Support (e.g., CNF–NH₂) | Provides anchoring sites for metal precursors, enabling the formation of atomically dispersed metal sites after pyrolysis [16]. |

| Metal Salts (e.g., H₂PtCl₆, FeCl₃) | Serve as precursors for the active metal components. The choice of anion (e.g., Cl⁻) can influence the synthesis and final structure [16] [19]. |

| Synchrotron Radiation Beamtime | Essential for performing in situ/operando XAS and FTIR to determine atomic structure and track reaction intermediates in real-time [16]. |

| Three-Electrode Electrochemical Cell | The standard setup for fundamental electrochemical measurements. A stable reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) is critical for accurate potential control and measurement [17] [20]. |

| Ion-Exchange Membrane | Used in the assembly of advanced testing devices like anion-exchange-membrane water electrolyzers (AEMWE) to evaluate catalyst performance under industrially relevant conditions [19]. |

Visualizing the Scaling Relation and Breakthrough Strategies

The following diagrams illustrate the core problem and the catalyst design solutions.

Diagram 1: The single-site catalyst performance limitation cascade.

Diagram 2: Catalyst design strategies to overcome scaling relations.

Beyond the Limit: Methodological Strategies for Disrupting Adsorption-Energy Scaling Relations

Dynamic Structural Regulation of Active Sites via Intramolecular Proton Transfer

Linear scaling relationships (LSRs) impose fundamental limitations on multi-step catalytic reactions by creating inherent correlations between the adsorption energies of different reaction intermediates. This prevents the independent optimization of each catalytic step, thereby placing a ceiling on achievable activity and selectivity [1] [21]. Dynamic structural regulation of active sites via intramolecular proton transfer represents an emerging strategy to circumvent these limitations. By enabling real-time modulation of the electronic structure and coordination environment of catalytic centers, this approach allows simultaneous optimization of multiple reaction steps that would traditionally compete within constrained scaling relationships [1].

This technical support resource provides experimental methodologies and troubleshooting guidance for researchers investigating dynamic proton transfer processes in catalytic systems, with particular emphasis on applications in oxygen electrocatalysis and related fields where breaking scaling relationships offers transformative potential [16].

Key Concepts and Fundamental Mechanisms

Understanding Scaling Relationships in Catalysis

In conventional heterogeneous catalysis, the adsorption energies of key intermediates (e.g., *OH, *O, and *OOH in oxygen evolution reaction) are linearly correlated, creating an inherent trade-off that limits optimal catalyst design [1] [16]. For instance, strengthening *OOH adsorption typically strengthens *OH adsorption to a similar degree, making it impossible to independently optimize both interactions. This scaling relationship manifests as a fundamental bottleneck across numerous catalytic processes, including oxygen evolution reaction (OER), oxygen reduction reaction (ORR), and CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR) [1] [22] [16].

Dynamic Structural Regulation Principle

The dynamic structural regulation strategy employs intramolecular proton transfer to trigger coordinated structural changes that simultaneously optimize the energetics of multiple catalytic steps. In the Ni-Fe system, proton transfer drives Ni-adsorbate coordination changes that modulate the electronic structure of adjacent Fe centers, thereby lowering energy barriers for both O–H bond cleavage and O–O bond formation within the same catalytic cycle [1]. This mechanism operates through:

- Real-time coordination evolution of metal centers during catalysis

- Electronic structure modulation of active sites via proton-coupled electron transfer

- Dual-site cooperation enabling simultaneous optimization of competing reaction steps

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of Dynamic Regulation in Model Catalytic Systems

| Catalytic System | Reaction | Performance Metric | Improvement vs. Conventional | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni-Fe₂ molecular complex [1] | OER | Intrinsic activity | Notable enhancement | Dynamic Ni-adsorbate coordination alters Fe electronic structure |

| Pt = N₂ = Fe atomic-bridge assembly [16] | ORR | Kinetic current density @ 0.95V | ~100× vs. Pt/C | Direct O–O breakage via Pt–O–O–Fe intermediate |

| Fe-Ni@BN dual-atom catalyst [22] | CO₂RR | Selectivity to CH₄ | Enhanced | Breaks scaling between OCHO* and OCHOH* adsorption |

Experimental Protocols

Synthesis of Ni-Fe Molecular Complex Catalyst

Objective: Construct a dynamically regulated Ni-Fe molecular catalyst via in situ electrochemical activation [1].

Materials:

- Graphene oxide (GO) aqueous suspension

- Nickel vessel (for hydrothermal assembly)

- High-purity KOH electrolyte

- Fe ion source (e.g., FeCl₃·6H₂O)

- Argon gas for inert atmosphere

Procedure:

- Pre-catalyst Synthesis:

- Seal GO suspension in Ni vessel at 80°C to assemble 3D Ni(OH)₂/graphene hydrogel

- Freeze-dry resulting hydrogel to form aerogel

- Thermally anneal at 700°C under Ar atmosphere to form Ni single atoms trapped in holey graphene nanomesh (Ni-SAs@GNM)

- Apply acid treatment to remove nanoparticles, leaving atomically dispersed Ni sites

- Electrochemical Activation:

- Load Ni-SAs@GNM pre-catalyst onto glassy carbon working electrode

- Employ standard three-electrode system with purified Fe-free 1 M KOH electrolyte

- Deliberately add 1 ppm Fe ions to electrolyte

- Perform cyclic voltammetry between 1.1 and 1.65 V vs. RHE until activation complete

- Alternative: Use anodic chronopotentiometry or chronoamperometry for activation

Validation:

- Confirm atomic dispersion via aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM

- Verify Fe incorporation via synchrotron-based X-ray fluorescence (SXRF)

- Determine local structure changes via operando XAFS

Diagram 1: Ni-Fe Catalyst Synthesis Workflow

Operando XAFS Characterization

Objective: Probe dynamic structural evolution of active sites during catalysis [1].

Materials:

- Synchrotron radiation source

- Electrochemical cell with X-ray transparent windows

- Potentiostat/galvanostat

- Reference electrodes (RHE)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare thin electrode films for transmission measurements

- Ensure appropriate metal loading for optimal signal-to-noise

Data Collection:

- Acquire XANES spectra at metal K-edges under operating conditions

- Collect EXAFS data across relevant potential range

- Perform quick-scanning EXAFS for time-resolved studies

Data Analysis:

- Process data using standard demethylation procedures

- Fit EXAFS spectra to determine coordination numbers and bond distances

- Monitor changes in oxidation state via edge position shifts

Troubleshooting:

- If radiation damage occurs, reduce beam intensity or use faster scanning

- For poor signal quality, optimize sample thickness or increase integration time

Electrokinetic Analysis for Proton Transfer Studies

Objective: Quantify kinetics and identify rate-determining steps in proton-coupled electron transfer processes.

Materials:

- Potentiostat with high current resolution

- Rotating disk electrode (RDE) or rotating ring-disk electrode (RRDE)

- High-purity electrolytes with controlled proton concentrations

Procedure:

- Tafel Analysis:

- Measure steady-state polarization curves

- Plot overpotential vs. log(current density)

- Extract Tafel slopes to identify possible rate-determining steps

Reaction Order Determination:

- Measure current density at fixed overpotential while varying reactant concentration

- Plot log(current) vs. log(concentration) to determine reaction orders

Isotope Effect Studies:

- Compare kinetics in H₂O vs. D₂O-based electrolytes

- Calculate kinetic isotope effect (KIE) as kH/kD

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs

Q1: Our catalyst shows negligible improvement in OER activity after Fe incorporation. What could be wrong?

A1: Several factors could explain limited activity enhancement:

- Insufficient Fe anchoring: Ensure your Ni pre-catalyst has adequate anchoring sites. Characterize pre-catalyst with HAADF-STEM to confirm atomic dispersion [1].

- Improper electrochemical activation: Extend activation cycles or try potentiostatic activation at intermediate potentials (1.3-1.4 V vs. RHE) [1].

- Fe contamination in electrolyte: Use ultra-high purity KOH and validate Fe-free conditions before deliberate Fe addition.

Q2: Operando XAFS shows no evidence of dynamic structural changes during catalysis. What are potential causes?

A2: The absence of observable dynamics may stem from:

- Insufficient time resolution: Dynamic coordination changes can be transient. Implement quick-scanning EXAFS or dispersive XAFS for better time resolution [1].

- Inappropriate potential window: Ensure you're scanning potentials relevant to the catalytic turnover.

- Limited proton mobility: Incorporate proton donors/acceptors in proximity to active sites to facilitate intramolecular proton transfer [1] [23].

Q3: The catalyst exhibits excellent initial activity but rapid degradation. How can stability be improved?

A3: Stability issues in dynamically regulated catalysts often originate from:

- Metal dissolution: Implement strong metal-support interactions through appropriate coordination environments (e.g., N-bridging) [16].

- Structural collapse: Ensure support stability by using corrosion-resistant materials like heteroatom-doped carbons [24].

- Active site aggregation: Introduce spatial confinement through molecular scaffolds or coordination templates [1] [16].

Q4: How can we distinguish intramolecular proton transfer from intermolecular pathways?

A4: Several experimental approaches can differentiate these mechanisms:

- Isotope effect studies: Intramolecular proton transfer typically exhibits smaller KIE (2-4) versus intermolecular pathways (>7) [23].

- Solvent dependence: Intramolecular processes show minimal solvent dependence compared to intermolecular pathways [23].

- Structural constraints: Systematically vary distance between proton donor and acceptor sites; intramolecular transfer requires precise spatial arrangement [1] [23].

Q5: Our theoretical calculations suggest broken scaling relationships, but experimental performance remains limited. Why?

A5: This discrepancy may arise from:

- Non-ideal reaction pathways: The catalyst may follow alternative mechanisms that bypass the theoretically optimized pathway.

- Mass transport limitations: Ensure measurements are conducted in kinetically controlled regime using RDE at appropriate rotation rates.

- Incomplete active site formation: Characterize actual active sites under working conditions; theoretical models often assume ideal structures that may not form experimentally [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Dynamic Proton Transfer Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Atom Pre-catalysts | Ni-SAs@GNM, Fe-SAs@GNM [1] | Foundation for constructing molecular complexes | Atomic dispersion critical; characterize with HAADF-STEM |

| Metal Precursors | H₂PtCl₆, FeCl₃·6H₂O, Ni salts [16] | Introduce active metal centers | Purity essential to avoid unintended doping |

| Molecular Bridges | Nitrogen-containing ligands [16] | Create defined atomic spacing for dual-site mechanisms | Coordination strength affects stability under potential cycling |

| High-Purity Electrolytes | Fe-free KOH, purified H₂SO₄ [1] | Provide reaction environment and protons | Trace metal contaminants can poison active sites |

| Isotope-labeled Solvents | D₂O, H₂¹⁸O [23] | Mechanistic studies through KIE and oxygen tracking | Exclusion of atmospheric contaminants critical |

| Support Materials | Graphene nanomesh, N-doped carbon [1] [16] | Anchor single atoms and facilitate electron transfer | Defect engineering enhances metal-support interactions |

Advanced Applications and Mechanism Elucidation

Dual-Site Mechanism in Oxygen Reduction

The N-bridged Pt = N₂ = Fe atomic-scale assembly exemplifies how dynamic regulation enables alternative reaction mechanisms that circumvent conventional scaling relationships. This system promotes direct O–O bond breakage without forming *OOH intermediates, following a dual-site mechanism characterized by a key Pt–O–O–Fe transition state [16]. The interatomic distance between Pt and Fe (∼2.8-2.9 Å) is critical for enabling this pathway, which demonstrates nearly two orders of magnitude enhancement in kinetic current density compared to conventional Pt/C catalysts [16].

Diagram 2: Dual-Site vs Single-Site ORR Mechanisms

Computational Modeling Guidance

DFT Protocol for Proton Transfer Systems:

- Model Construction:

- Build cluster models with explicit second-sphere coordination

- Include sufficient support environment to capture metal-support interactions

- Model solvation effects using implicit or explicit solvent models

Reaction Pathway Mapping:

- Identify possible proton transfer pathways and associated energy barriers

- Calculate scaling relationships between key intermediates

- Model dynamic structural changes through constrained optimization or ab initio MD

Electronic Structure Analysis:

- Compute projected density of states to identify orbital interactions

- Calculate Bader charges to track electron redistribution during proton transfer

- Analyze charge density differences to visualize bonding changes

Machine Learning Integration:

- Use descriptor-based models to rapidly screen candidate systems

- Implement neural network potentials for accurate dynamics simulations

- Apply symbolic regression to discover new scaling relationships

The strategic application of dynamic structural regulation via intramolecular proton transfer represents a paradigm shift in catalyst design that directly addresses the fundamental limitations imposed by linear scaling relationships. The experimental protocols, troubleshooting guidelines, and mechanistic insights provided in this technical resource establish a foundation for systematic investigation of these complex dynamic systems. As research in this field advances, the integration of sophisticated operando characterization with computational modeling will continue to unravel the intricate interplay between proton transfer, structural dynamics, and catalytic function, enabling the rational design of next-generation catalysts with transformative performance capabilities across energy conversion and chemical transformation technologies.

FAQs: Understanding the Mechanism and Its Challenges

Q1: What is the primary kinetic advantage of bypassing the *OOH intermediate in the Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR)?

A1: Bypassing the *OOH intermediate via a dissociative mechanism avoids the rate-limiting step of its formation, which traditionally requires overcoming a high Gibbs free energy barrier (ΔG) [25]. This mechanism facilitates direct O-O bond cleavage, enabling rapid ORR kinetics. In practice, catalysts employing this pathway, such as those with abundant sp3-hybridized carbon defects, have demonstrated excellent performance with onset potentials of 1.02 V and half-wave potentials of 0.90 V [25].

Q2: How do dual-site catalysts fundamentally differ from single-atom catalysts in managing reaction intermediates?

A2: Single-atom catalysts feature uniform active sites, which can limit performance in complex reactions involving multiple intermediates because they cannot optimally adjust the adsorption of every intermediate simultaneously [6]. In contrast, dual-site catalysts, or Integrative Catalytic Pairs (ICPs), feature spatially adjacent, electronically coupled active sites that function cooperatively [6]. This allows for functional differentiation within the catalytic ensemble, enabling the system to stabilize different transition states or intermediates at different sites, thereby circumventing the linear scaling relationships (LSRs) that constrain single-site catalysts [6] [11].

Q3: What are the key characterization techniques for verifying a direct O-O cleavage pathway and the dynamic nature of active sites?

A3: A combination of advanced techniques is required:

- Operando X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (XAFS): Essential for probing the local coordination environment of metal active sites during electrochemical operation. This technique can verify dynamic structural changes, such as the evolution of a Ni-Fe2 trimer structure during OER [11].

- Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations: Used to map reaction pathways, calculate the free energy (

ΔG) of reaction steps, and identify the critical role of orbital interactions. For instance, DFT can show how sp3 carbon provides electrons to oxygen's π* and σ* anti-bonding orbitals, facilitating O2 adsorption and OH desorption [25]. - Electrokinetic Studies: Analyzing parameters like Tafel slopes can help distinguish between different reaction mechanisms and rate-determining steps [11].

Troubleshooting Guides for Experimental Research

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

When working with advanced catalytic systems designed for direct O-O cleavage, researchers may encounter several challenges. The table below outlines common issues, their potential causes, and recommended corrective actions.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Catalytic Activity | • Insufficient density of active sites.• Incorrect electronic structure of metal centers.• Catalyst surface area is too low. | • Optimize synthesis to increase sp3 carbon content or dual-site density [25].• Fine-tune the coordination environment of metal centers via precursor selection [11].• Use template-assisted strategies to achieve high specific surface area (e.g., 1120 m²/g) [25]. |

| Poor Stability During Electrolysis | • Degradation or agglomeration of active sites.• Structural collapse of the support material.• Unfavorable reaction intermediates causing poisoning. | • Implement a stabilizing matrix (e.g., holey graphene nanomesh) [11].• Perform operando characterization to identify degradation pathways [11]. |

| Inability to Detect Key Intermediates | • Intermediates are too short-lived.• Low concentration of intermediates on the surface.• Inappropriate characterization technique. | • Utilize computational methods (DFT) to predict intermediate stability and binding energies [25].• Employ surface-sensitive in situ techniques (ATR-SEIRAS). |

| Failure to Break Scaling Relationships | • Active sites are too uniform (single-site limitation).• Lack of dynamic cooperation between adjacent sites.• Inter-site distance is not optimal for bridge-model bonding. | • Design catalysts with integrative catalytic pairs (ICPs) for functional differentiation [6].• Aim for systems that exhibit dynamic structural regulation under reaction conditions [11]. |

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol: Synthesis of N-doped Defective Carbon with sp3-Hybridized Defects

This protocol is adapted from the synthesis of a metal-free carbon electrocatalyst with high sp3 content, which demonstrated high ORR activity via a dissociative mechanism [25].

Objective: To fabricate graphene-like, N-doped defective carbon with abundant pentagonal sp3 carbon structures via high-temperature pyrolysis of silk using a vaporized-salt template.

Materials:

- Silk (source of carbon and nitrogen)

- Deionized (DI) water

- KCl (2 M solution)

- LiCl (2 M solution)

- Tube furnace with N2 atmosphere

- Aqueous HCl (1 M)

Procedure:

- Silk Pre-treatment: Immerse the silk in DI water for 24 hours. Afterwards, dry it at 60°C for 6 hours.

- Salt Impregnation: Cut the washed silk into pieces (2 cm x 2 cm). Immerse them in a 60 mL mixed solution containing 2 M KCl and 2 M LiCl for 24 hours.

- Drying: Transfer the mixture to a culture dish and dry at 60°C.

- Pyrolysis: Place the dried sample in a tube furnace and anneal at 900°C for 2 hours under a continuous N2 atmosphere to form graphene-like carbon (GC).

- Purification: To remove potential metal impurities, treat the obtained sample with 1 M aqueous HCl solution, followed by thorough washing with DI water and drying.

Key Characterization:

- The successful incorporation of sp3-hybridized carbon (content can reach 43.7%) can be confirmed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and Raman spectroscopy [25].

- The specific surface area (BET method) of the final material can be as high as 1120.83 m²/g [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents used in the synthesis and testing of advanced catalysts for direct O-O cleavage, as featured in the cited research.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Silk (as a biomass precursor) | Serves as a source of both carbon and nitrogen for creating N-doped carbon frameworks with inherent heteroatoms and molecular structures that can form topological defects [25]. |

| KCl / LiCl (mixed salt template) | Acts as a vaporized-salt template during high-temperature pyrolysis. This process helps create ultra-thin, high-surface-area carbon structures with abundant defects [25]. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) Suspension | Used as a foundational support material for constructing single-atom pre-catalysts. It can be formed into a 3D hydrogel and subsequently processed into a holey graphene nanomesh [11]. |

| Fe ions (e.g., from Fe salts) | Deliberately added in ppm quantities to an electrolyte to enable the in situ electrochemical construction of bimetallic active sites, such as the O-bridged Ni-Fe2 trimer complex [11]. |

| Purified KOH Electrolyte | Used for electrochemical activation and testing under alkaline conditions. High purity is critical to avoid unintended contamination by trace metals that could influence catalyst formation [11]. |

Catalytic Pathway Visualization

Diagram 1: Dissociative ORR pathway bypassing *OOH intermediate.

Diagram 2: Dynamic cooperation mechanism in Ni-Fe catalyst for OER.

Engineering Multifunctional Surfaces and Interfacial Sites for Intermediate Stabilization

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers developing advanced catalysts to overcome linear scaling relationships (LSRs) in multi-step reactions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our catalyst synthesis consistently yields inconsistent Ni-Fe distributions. What could be the cause? Inconsistent atomic distribution in bimetallic catalysts like Ni-Fe complexes often stems from non-uniform precursor deposition or inadequate control during the electrochemical activation step. Ensure your graphene oxide support has uniform defect sites for metal anchoring and control the Fe ion concentration precisely in the ppm range during electrochemical activation. Using a purified KOH electrolyte is essential to prevent unintended metal contamination that competes with active site formation [11].

Q2: We observe a gradual decline in catalyst conversion efficiency during oxygen evolution reaction (OER). What troubleshooting steps should we follow? A gradual decline in activity often indicates catalyst deactivation. Systematically check these parameters [26]:

- Thermal degradation: Verify operating temperatures haven't exceeded design limits causing sintering

- Chemical poisoning: Analyze feed composition for contaminants (sulfur compounds commonly poison metal catalysts)

- Structural changes: Perform post-reaction characterization to check for active site agglomeration or carbon buildup

- Operando analysis: Implement techniques like X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) to monitor active site evolution under reaction conditions [11]

Q3: What is the significance of the water/chloride molar ratio in catalytic reforming, and how is it controlled? Maintaining proper water/chloride balance (typically 15-25 molar ratio) is crucial for balancing the acidic and metal functions of reforming catalysts. This is controlled through:

- Online monitoring systems for water and chloride concentrations in recycle gas

- Sample facilities for regular compositional analysis

- Following licensor-specific equilibrium curves for chloride management

- Adjusting water injection rates based on catalyst chloride content and operating temperature [27]

Q4: How can we verify if channeling is occurring in our fixed-bed catalytic reactor? Channeling in fixed-bed reactors can be confirmed through these diagnostic methods:

- Measure temperature variations across the reactor bed - variations exceeding 6-10°C indicate flow maldistribution

- Monitor differential pressure trends - unexpected DP changes often signal channeling

- Check for difficulty meeting product specifications despite normal operating parameters

- Implement a well-designed pattern of radial bed thermocouples for accurate monitoring [26]

Troubleshooting Guides

Catalyst Synthesis and Characterization Issues

| Symptom | Possible Causes | Diagnostic Methods | Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low catalytic activity | Incorrect metal coordination, Sintering of active sites, Poisoning by feed impurities [26] | XAFS, XPS, ICP-OES [11] | Optimize electrochemical activation, Use purified electrolytes, Control feed quality [11] |

| Poor stability | Phase transformations, Carbon buildup, Active species volatilization [26] | In-situ XAFS, TEM, TPO [11] | Modify support interactions, Introduce protective layers, Control reaction severity [28] |

| Unselective product distribution | Unbalanced acid/metal sites, Incorrect intermediate stabilization [26] | Kinetic analysis, Isotope labeling, DFT calculations [11] | Tune water/chloride ratio, Engineer dual active sites, Optimize operating conditions [27] [11] |

Reactor Operation and Performance Issues

| Symptom | Possible Causes | Diagnostic Methods | Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature runaway | Loss of quench gas, Hot spots from flow maldistribution, Feed composition changes [26] | Radial temperature profiling, Feed analysis, Pressure monitoring [26] | Install better flow distributors, Implement feed quality control, Ensure adequate cooling capacity [26] |

| Rapid pressure drop increase | Catalyst fines from poor loading, Feed precursors for polymerization, Channeling [26] | DP monitoring, Catalyst sampling, Radioactive tracing | Improve catalyst loading procedures, Implement feed pre-treatment, Add in-line filters [26] |

| Unexpected selectivity changes | Feed contaminants, Altered water/chloride balance, Catalyst poisoning [26] [27] | Recycle gas analysis, Catalyst characterization, Feed impurity testing | Install guard beds, Adjust water injection rates, Implement stricter feed specifications [27] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Ni-Fe Molecular Complex Catalyst via Electrochemical Activation

Principle: Construct dynamic dual-site catalysts through in situ electrochemical conversion of single-atom precursors to achieve intermediate stabilization beyond LSRs [11].

Materials:

- Graphene oxide (GO) aqueous suspension

- High-purity Ni vessel

- Argon atmosphere furnace

- Purified Fe-free 1 M KOH electrolyte

- Fe standard solution for precise ppm-level addition

- Standard three-electrode electrochemical cell

Procedure:

- Pre-catalyst Preparation:

- Seal GO suspension in Ni vessel at 80°C for 24 hours to form 3D Ni(OH)₂/graphene hydrogel

- Freeze-dry the resulting hydrogel to preserve structure

- Thermally anneal at 700°C under Ar atmosphere to form Ni single atoms on holey graphene nanomesh (Ni-SAs@GNM)

- Apply acid treatment to remove nanoparticles, leaving only atomic Ni dispersions

Electrochemical Activation:

- Load Ni-SAs@GNM onto glassy carbon working electrode

- Use purified 1 M KOH electrolyte with deliberate addition of 1 ppm Fe ions

- Perform cyclic voltammetry between 1.1 and 1.65 V vs. RHE until stable OER performance achieved

- Alternative activation methods: anodic chronopotentiometry or chronoamperometry

Characterization:

- Confirm atomic dispersion via aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM

- Determine oxidation states through XPS and L₂,₃-edge XAS

- Verify local structure via operando XAFS measurements

- Elemental distribution analysis through SXRF spectroscopy and EDS mapping [11]

Protocol 2: Operando XAFS Analysis for Dynamic Active Site Monitoring

Principle: Track the coordination evolution of active sites during catalysis to understand dynamic structural changes that enable LSR circumvention [11].

Materials:

- Synchrotron radiation facility with operando electrochemical cell

- Custom-designed Teflon cell with X-ray transparent windows

- Potentiostat for potential control during measurements

- Reference electrodes (RHE) calibrated immediately before experiments

Procedure:

- Cell Assembly:

- Prepare electrode with catalyst loading optimized for X-ray absorption

- Integrate working, counter, and reference electrodes in operando cell

- Ensure precise alignment for X-ray path through electrode interface

Data Collection:

- Acquire Ni K-edge and Fe K-edge spectra under open circuit conditions

- Collect data at progressively increasing applied potentials covering OER region

- Perform quick-scanning EXAFS to capture transient intermediates

- Record simultaneous electrochemical data (current, potential)

Data Analysis:

- Process data using standard procedures (background subtraction, normalization)

- Perform linear combination analysis to identify species evolution

- Extract structural parameters (coordination numbers, bond distances) through EXAFS fitting

- Correlate structural changes with electrochemical performance [11]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Graphene Oxide Support | Provides high-surface-area with defined anchoring sites | Ensure uniform holey structure with 20-60 nm pores for optimal metal dispersion [11] |

| Ni-Fe Molecular Complex | Dynamic dual-site OER catalyst | Synthesized via electrochemical activation; enables intramolecular proton transfer [11] |

| Operando XAFS Setup | Monitors atomic-scale structural changes during operation | Requires synchrotron source; provides real-time coordination environment data [11] |

| Purified KOH Electrolyte | Prevents contamination during electrochemical activation | Essential for controlled Fe incorporation at ppm levels [11] |

| Single-Atom Pre-catalysts | Precursors for complex active sites | Ni-SAs@GNM provides defined starting point for electrochemical transformation [11] |

Performance Metrics for Advanced Catalysts

| Catalyst System | OER Activity | Stability | Key Innovation | LSR Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni-Fe Molecular Complex [11] | Notable intrinsic OER activity | Maintained under operation | Dynamic dual-site cooperation | Intramolecular proton transfer alters electronic structure |

| Cu₃N (001) Surface [29] | Better HER than Pt-based catalysts | Not specified | Multifunctional capability | Unique N and Cu atom coordination |

| Integrative Catalytic Pairs [6] | Enhanced multi-step reaction efficiency | Improved selectivity | Spatially adjacent dual sites | Functional differentiation within ensemble |

| LDH-Based Composites [28] | Enhanced photocatalytic H₂ production | Tunable stability | Surface and interface engineering | Band alignment tailoring and defect creation |

Diagnostic Diagrams

Catalyst Troubleshooting Diagnostic Flow

Breaking Scaling Relationships via Surface Engineering

Utilizing Confinement Effects and Proton Acceptors to Alter Adsorption Geometries

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance for researchers working to overcome catalytic scaling relationships by manipulating adsorption geometries.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

Q1: My catalyst shows unwanted adsorption geometry, leading to poor selectivity. How can I influence this?

- Problem: The reactant molecules adsorb onto the active site in a geometry that leads to an undesired reaction pathway or product.

- Solution & Protocol: Implement spatial confinement using 1D nanochannels.

- Select a Confining Support: Choose a support material with well-defined, tunable nanochannels, such as ultra-thin C4N3 nanotubes [30] or Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) [31].

- Functionalize the Nanochannel: Anchor single-atom catalytic sites (e.g., Transition Metal (TM) atoms like Mn, Cr, or Mo) to the inner wall of the nanochannels to create a confined reaction environment [30].

- Mechanism: The nanoscale walls of the channel physically constrain how reactant molecules can approach and orient themselves on the active site. This can force a switch from an "end-on" to a more favorable "side-on" adsorption geometry for molecules like N₂, which is crucial for activating strong covalent bonds [30].

Q2: My highly reactive catalyst deactivates rapidly during operation. How can confinement improve stability?

- Problem: The catalyst, especially those used in aggressive reactions like Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs), loses activity due to leaching of active species or over-oxidation.