Optimizing Catalyst Pore Structure and Surface Area: Strategies for Enhanced Performance and Stability

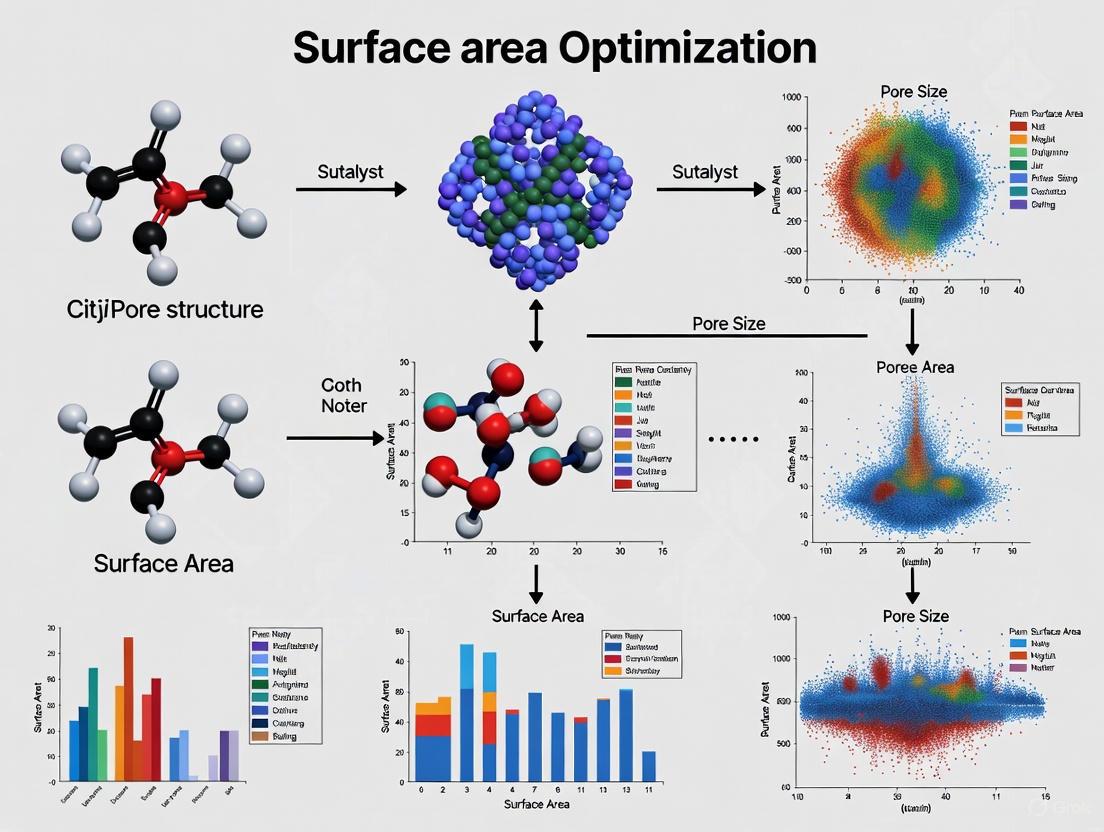

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies for optimizing catalyst pore structure and specific surface area, critical determinants of activity, selectivity, and longevity.

Optimizing Catalyst Pore Structure and Surface Area: Strategies for Enhanced Performance and Stability

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies for optimizing catalyst pore structure and specific surface area, critical determinants of activity, selectivity, and longevity. Tailored for researchers and scientists, we explore foundational principles linking pore architecture to mass transfer and reactivity. The content details advanced synthesis methodologies, characterization techniques, and data-driven optimization approaches. A strong emphasis is placed on troubleshooting common deactivation mechanisms and implementing stability-enhancing designs. The review synthesizes experimental and computational validation frameworks, offering a holistic guide for the rational design of next-generation high-performance catalysts across energy, environmental, and chemical synthesis applications.

The Fundamental Principles of Catalyst Porosity and Surface Area

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between pore size distribution and porosity? Porosity is a single value representing the total void volume fraction in a solid material. In contrast, pore size distribution (PSD) describes the relative abundance of pores of different sizes within the total pore space, providing a much more detailed characterization of the pore network [1] [2]. While porosity indicates how much fluid a material can hold, PSD helps predict how easily that fluid can move through the material and access the internal surface area.

Q2: Which technique should I use to characterize nanopores in my catalyst sample? For nanopores (pore widths typically less than 2 nm), low-pressure gas adsorption analysis is the most suitable method. The technique uses gases like N₂ or CO₂ and is based on the Kelvin equation, allowing for the characterization of pores in the range of ~0.35 nm to ~400 nm [3] [4]. Density Functional Theory (DFT) analysis of the adsorption data is the modern method for obtaining accurate pore size distributions in this range.

Q3: My mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) results seem to underestimate the volume of large pores. Why could this be? This is a common limitation of MIP known as the "ink-bottle effect." Mercury intrusion is controlled by pore throat sizes, not the pore body sizes. A large pore body that is accessible only through a narrow pore throat will be misinterpreted by MIP as having the volume of the large pore but the size of the small throat. This can lead to an underestimation of the volume fraction of larger pores [2].

Q4: How does pore connectivity impact my catalyst's performance? Pore connectivity directly influences mass transport and permeability. A material can have high porosity, but if the pores are poorly interconnected (e.g., many blind or closed pores), reactant molecules cannot efficiently reach, or product molecules cannot leave, the active catalytic sites on the internal surface. This can significantly reduce the catalyst's apparent activity and efficiency [5] [4].

Q5: Can I use the BET method to measure closed pores? No, the BET method and other gas adsorption techniques cannot measure closed pores. These methods rely on the physical adsorption of gas molecules onto surfaces that are accessible via an open pore network. Closed pores, being completely isolated from the external surface, are not probed by the adsorbate gas [5] [3].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Low reproducibility in BET surface area measurements.

- Potential Cause 1: Inadequate or inconsistent sample degassing.

- Solution: Ensure a rigorous and standardized degassing protocol before analysis. This involves applying heat and vacuum to the solid sample to remove any initially adsorbed contaminants like water vapor and carbon dioxide [3].

- Potential Cause 2: Sample heterogeneity.

- Solution: Increase the number of replicate measurements. Ensure the sample is ground and mixed thoroughly to obtain a representative sub-sample for analysis.

Problem: Discrepancies between pore size distributions from different techniques (e.g., MIP vs. Gas Adsorption).

- Potential Cause: Different physical principles and inherent limitations of each technique.

- Solution: Understand that each method measures a different aspect of the pore system. MIP tends to be sensitive to pore throat sizes and is ideal for macropores and mesopores. Gas adsorption is excellent for micropores and mesopores and provides information about pore bodies. Use these techniques complementarily, not as direct replacements. For instance, MIP covers a pore size range from approximately 3 nm to 600 µm, while gas adsorption is best for pores from 0.35 nm to 400 nm [5] [3] [2].

Problem: Sample deformation during Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry.

- Potential Cause: High mercury intrusion pressure damaging the delicate pore structure.

- Solution: Be aware that this is a known risk, especially for soft or compressible materials. The high pressure required to intrude mercury into very small pores can compress the sample skeleton, leading to inaccurate data [2] [4]. Consider using alternative, lower-pressure methods like gas adsorption for fragile microporous and mesoporous materials, or use imaging techniques like micro-CT [2].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Standard Protocol for BET Surface Area and Pore Size via Gas Adsorption

This protocol is based on the principles of gas physisorption analysis [3].

- Sample Preparation: A solid sample of known mass is placed in a sealed analysis tube.

- Degassing: The sample is heated under vacuum for a specified duration to remove all adsorbed contaminants (e.g., water, CO₂) from its surface and pores.

- Cooling: The sample is cooled to cryogenic temperature (typically using liquid nitrogen, 77 K).

- Analysis:

- The sample is exposed to increments of an adsorbate gas (usually N₂).

- After each dose, the system is allowed to reach equilibrium, and the quantity of gas adsorbed is measured.

- The pressure is increased incrementally until saturation pressure is approached, completing the adsorption branch.

- The pressure is then incrementally decreased, and the quantity of gas desorbed is measured to create the desorption branch.

- Data Analysis:

- The data is plotted as an adsorption/desorption isotherm (quantity adsorbed vs. relative pressure).

- The BET (Brunauer, Emmett, and Teller) equation is applied to the low-pressure region of the isotherm to calculate the specific surface area.

- The DFT (Density Functional Theory) or BJH (Barrett, Joyner, Halenda) method is applied to the full isotherm to determine the pore size distribution and pore volume.

Protocol for Investigating Pore Structure in Cementitious Materials using NMR

This protocol is derived from a study on magnetic slurry [6].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare cement-based slurry samples (e.g., with and without magnetic field treatment, and with varying admixture content like 15-25% magnetic powder).

- Curing: Allow the samples to set and cure under controlled conditions.

- Durability Testing (Optional but correlated): Subject samples to accelerated durability tests, such as:

- Freeze-thaw cycles: Typically 50 cycles between -20 °C and 20 °C. Measure strength and mass loss rates after cycling [6].

- Sulfate erosion exposure: Immerse samples in a sulfate solution and monitor changes.

- Pore Structure Analysis: Use Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) technology on the samples to quantitatively analyze the evolution of the pore structure. NMR is effective at measuring parameters like micro-pore throat volume [6].

- Data Correlation: Correlate the changes in pore size distribution (e.g., reduction in capillary pores) from NMR data with the performance results from durability tests.

Quantitative Data from Material Studies

Table 1: Pore Structure Modification in Magnetic Field-Treated Slurry [6]

| Magnetic Powder Content | Magnetic Field | Key Pore Structure Result | Durability Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15% | 0.5 T | Micro-pore throat volume decreased by 23.35% (via NMR) | Data not specified in abstract |

| 20% | Applied | Reduction in capillary channels and porosity | Strength loss rate after 50 freeze-thaw cycles was 2.14% |

| 25% | Applied | Data not specified in abstract | Resistance to sulphate erosion improved by 14.4% compared to control group |

Table 2: Overview of Common Pore Structure Characterization Techniques [5] [3] [2]

| Technique | Typical Pore Size Range | Measured Principle | Ideal For | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas Adsorption (BET/DFT) | ~0.35 nm – 400 nm | Physisorption of gas molecules | Micropores and mesopores; specific surface area measurement | Cannot detect closed pores; lower limit on absolute surface area (~0.5 m²) [3] |

| Mercury Intrusion (MIP) | 3 nm – 600 µm | intrusion of a non-wetting liquid | Macropores and mesopores; pore throat sizes | "Ink-bottle" effect; high pressure may damage sample; measures pore throats, not bodies [5] [2] |

| Capillary Flow Porometry | 0.015 µm – 500 µm | Gas displacement of a wetting liquid | Through-pores in membranes and sheets; bubble point measurement | Only characterizes through-pores [5] |

| Digital Image Analysis | Wide range, depends on image resolution | Direct measurement from CT or SEM images | Pore geometry and connectivity; allows visualization of pore network in 3D | Resolution limits; complex algorithms required [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Pore Structure and Surface Area Experiments

| Material / Reagent | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Nitrogen Gas (N₂), 99.999% | The most common adsorbate gas for BET surface area and pore size analysis. It is used at cryogenic temperatures to physisorb onto solid surfaces [3]. |

| Liquid Nitrogen | Used to maintain the sample at a constant cryogenic temperature (77 K) during gas adsorption analysis, which is crucial for achieving stable physisorption [3]. |

| Micron-sized Fe₃O₄ | Used as a magnetic particle admixture in cementitious materials research. Under an external magnetic field, it can form ordered arrangements to densify the microstructure and reduce harmful pore volume [6]. |

| Degassed, High-Purity Mercury | The intrusive non-wetting fluid used in Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry. Its high surface tension requires pressure to enter pores, which is correlated to pore size [5]. |

| Waterborne Epoxy Resin | Used as an admixture in construction material studies to enhance slurry adhesion, toughness, and water resistance, which indirectly affects pore structure formation and durability [6]. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | A common chemical activator in the synthesis of geopolymers or activated materials from industrial by-products like slag and ash, significantly altering the pore network [7]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: Gas Adsorption Workflow for Surface Area and Pore Size.

Diagram 2: Technique Selection Guide for Different Pore Types.

In porous catalysts, the journey of a reactant molecule to an active site is as critical as the chemical reaction itself. The pore structure creates a physical landscape that governs mass transfer, creating a fundamental trade-off: high surface area often comes at the expense of accessible diffusion pathways. Hierarchical porous materials, which combine micropores ( 2 nm) with larger transport pores (mesopores 2-50 nm or macropores >50 nm), aim to resolve this conflict by providing both high surface area and efficient mass transfer [8] [9]. Understanding and optimizing this reaction-diffusion relationship is essential for advancing catalyst performance across industrial applications, from emission control to pharmaceutical synthesis.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Why does my catalyst with high surface area show lower-than-expected activity? Your catalyst is likely experiencing internal mass transfer limitations. While high surface area provides numerous active sites, reactants cannot reach them efficiently if the pore structure lacks interconnectivity or contains diffusion barriers [10]. The reactant concentration decreases significantly from the particle surface to its interior, leaving internal active sites underutilized [11]. To diagnose this issue, compare the reaction rates of your pellet catalyst versus its powdered form; a significant rate reduction in pellet form indicates severe diffusional limitations [11].

FAQ 2: How can I determine if my system is limited by reaction kinetics or mass transfer? The Thiele modulus and effectiveness factor are key diagnostic parameters [11] [10]. When increasing agitation speed or flow rate significantly enhances reaction rate, your system suffers from external mass transfer limitations [10]. If reducing catalyst particle size improves reaction rate, internal diffusion limitations are present [12] [11]. For a rigorous analysis, the Damköhler number (α) represents the ratio of reaction rate to diffusion rate; values greater than 1 indicate diffusion-limited regimes [10].

FAQ 3: What is the optimal pore size distribution for maximizing catalytic performance? A hierarchical structure with bimodal pore size distribution typically delivers optimal performance [8] [9]. Macropores or large mesopores ( 20 nm) act as "diffusion highways" to transport reactants deep into the particle [8]. Micropores provide high surface area for reactions and shape selectivity [9]. The optimal macroporosity depends on your specific reaction; for CO oxidation, increasing macroporosity from 33% to 58% significantly enhanced conversion by facilitating internal diffusion [13].

FAQ 4: How does catalyst particle size affect selectivity in porous catalysts? Smaller particles reduce diffusion path length, increasing reaction rates but potentially decreasing geometric selectivity [12] [14]. Larger particles enhance selectivity by creating longer, more discriminatory diffusion paths but reduce overall activity [12]. There exists a critical diffusion length (Lc) where geometric selectivity maximizes [12] [14]. For precise control, consider thin film configurations with programmable thickness to decouple selectivity from particle size constraints [12] [14].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Template-Assisted Spray Synthesis for Interconnected Macropores

This method creates spherical porous catalyst particles with controlled interconnected pore structures [13].

- Materials: Catalyst nanoparticles (e.g., TWC NPs), template particles (e.g., PMMA, 0.36 μm), ultrapure water, tubular furnace with temperature zones (250°C, 350°C, 500°C, 500°C), ultrasonic nebulizer, bag filter (150°C), nitrogen gas supply.

- Procedure:

- Prepare precursor by mixing catalyst nanoparticles (1 wt%) and PMMA template particles (0.1-3 wt%) in ultrapure water [13].

- Mechanically stir for 15 minutes followed by ultrasonication for 15 minutes to ensure uniform dispersion [13].

- Feed precursor into spray dryer using nitrogen carrier gas (0.1 MPa, 5 L/min) [13].

- Pass generated droplets through tubular furnace zones to remove solvent and form composite particles [13].

- Remove remaining template by calcination at 900°C (5°C/min heating rate) in air for 1 hour [13].

- Key Parameters: PMMA concentration controls macroporosity and framework thickness; higher concentrations increase interconnection but may cause structural collapse beyond optimal levels [13].

Protocol 2: Single-Particle Accessibility Measurement via Microfluidics

This technique directly assesses mass transfer and accessibility within individual porous particles [15].

- Materials: Microfluidic chip with observation chambers, fluorescent probe molecules, porous particles of interest, fluorescence microscope, syringe pump, image analysis software.

- Procedure:

- Immobilize a single porous particle within the microfluidic chamber [15].

- Introduce fluorescent probe molecules at controlled concentration and flow rate using syringe pump [15].

- Monitor and record fluorescence intensity within the particle over time using microscopy [15].

- Quantify uptake kinetics and spatial distribution of fluorescence using image analysis [15].

- Repeat with different probe sizes to assess size-dependent accessibility [15].

- Applications: Direct visualization of intraparticle diffusion, identification of mass transfer heterogeneities, evaluation of pore blockage effects [15].

Protocol 3: Controlling Diffusion Length in Thin-Film Catalysts

This approach programs reactant diffusion by controlling catalyst thickness in a microfluidic reactor [12] [14].

- Materials: MOF catalyst precursors, substrate for film deposition, microfluidic reactor cell, precision pump, cross-flow circulation system.

- Procedure:

- Deposit catalyst as monolithic thin film with controlled thickness using layer-by-layer epitaxy, chemical vapor deposition, or solution processing [12] [14].

- Mount thin film in cross-flow microfluidic reactor cell [12] [14].

- Control reactant solution volume ( 80 μL) in direct contact with catalyst layer [12] [14].

- Connect to larger circulating reservoir with cross-flow direction along catalyst bed [12] [14].

- Adjust flow rate (0.1-15 mL/min) to prevent pore blockage and control residence time [12] [14].

- Advantages: Film thickness directly defines diffusion length (LD), enabling precise optimization of both turnover frequency and geometric selectivity [12] [14].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Effect of Pore Structure on CO Oxidation Performance in Porous TWC Particles

| PMMA Template (wt%) | Macroporosity (%) | Framework Thickness (nm) | CO Conversion (%) | Primary Pore Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 [13] | ~33 [13] | ~85 [13] | ~65 [13] | Limited interconnection |

| 0.5 [13] | ~42 [13] | ~65 [13] | ~78 [13] | Moderate interconnection |

| 1.0 [13] | ~50 [13] | ~52 [13] | ~88 [13] | Developed interconnection |

| 2.0 [13] | ~58 [13] | ~38 [13] | ~95 [13] | Optimal interconnection |

| 3.0 [13] | N/D | N/D | Reduced [13] | Broken structure |

Table 2: Impact of Catalyst Loading on Pore Textural Properties and HCl Removal

| Catalyst Loading (Cu wt%) | Specific Surface Area (m²/g) | Total Pore Volume (cm³/g) | HCl Removal Efficiency (%) | Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw ACF [16] | 1565.1 [16] | 0.78 [16] | ~70 [16] | ~10,000 [16] |

| 0.04 [16] | 1498.3 [16] | 0.74 [16] | 83.6 [16] | 12,354.6 [16] |

| 0.06 [16] | 1452.7 [16] | 0.71 [16] | ~75 [16] | ~11,000 [16] |

| 0.08 [16] | 1398.5 [16] | 0.68 [16] | ~68 [16] | ~9,500 [16] |

| 0.10 [16] | 1342.7 [16] | 0.65 [16] | ~62 [16] | ~8,200 [16] |

Table 3: Pore Network Modeling Parameters for Hierarchical Porous Particles

| Structural Parameter | Impact on Net Reaction Rate | Optimal Range | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macroporosity [8] | Strong positive correlation; higher porosity enhances diffusion [8] | 40-60% [13] [8] | Cross-sectional FIB-SEM image analysis [13] |

| Pore Size Ratio (macro:nano) [8] | Critical parameter; higher ratios dramatically improve performance [8] | 10-100 [8] | Pore network modeling [8] |

| Particle Size [8] | Inverse relationship; smaller particles higher reaction rate [8] | <100 μm [8] | Single-particle microfluidic analysis [15] |

| Pore Connectivity [8] | High connectivity reduces tortuosity, enhances accessibility [8] | 4-6 coordination number [8] | Pore network modeling [8] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Pore Structure Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| PMMA Template Particles (0.36 μm) [13] | Creates macroporous structure after calcination | Generating interconnected pore networks in spray-dried catalysts [13] |

| CuMnOx Hopcalite Catalyst [16] | Redox-active mixed metal oxide for catalytic reactions | Modifying activated carbon fibers for enhanced HCl capture via chemisorption [16] |

| Fluorescent Probe Molecules [15] | Visualizing and quantifying mass transfer in pores | Single-particle accessibility studies in microfluidic devices [15] |

| Zr-based MOF Precursors (UiO-66-NH2) [12] [14] | Creating well-defined porous catalysts with tunable functionality | Diffusion-programmed catalysis in thin-film configurations [12] [14] |

Diagnostic Diagrams

Pore Structure Impact Pathways

Troubleshooting Workflow

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between geometric surface area and electrochemical active surface area (ECSA)?

Geometric surface area is the macroscopic, physical area of an electrode material. In contrast, the Electrochemical Active Surface Area (ECSA) refers to the effective surface area capable of participating in electrochemical reactions, representing the sites that are both electrically and electrolytically connected. For non-porous, flat electrodes, these values may be similar. However, for nanocatalysts or porous electrodes, the ECSA can be orders of magnitude larger than the geometric area, as it accounts for the intricate pore structure and nanoscale features that expose more active sites [17].

Q2: Why does a high surface area not always lead to high catalytic activity?

A high surface area is beneficial only if it translates to a high density of catalytically active sites and if those sites are accessible to reactants. A material may have high surface area, but if the active site density is low (few atoms/molecules are actually catalytic), the overall activity will be poor. Furthermore, if the pore structure is not interconnected or is too narrow, reactants cannot diffuse to the internal active sites, rendering them useless. Research on porous three-way catalyst (TWC) particles has confirmed that an interconnected pore structure is crucial for allowing gaseous reactants to effectively reach internal active sites, thereby linking high surface area to high catalytic performance [13].

Q3: How can I quantify the density of active sites in a catalyst?

The methodology depends on the catalyst type. For precious metals like Pt, methods like Hydrogen Underpotential Deposition (HUPD) or CO-stripping voltammetry are standard [17]. For non-precious metal catalysts, such as Me-N-C single-atom catalysts, techniques include:

- Cyanide Poisoning: An in situ method where the decrease in catalyst performance is correlated to the adsorption of cyanide ions on metal-based active sites, allowing for spectrophotometric quantification [18].

- Pulse Chemisorption/TPD: Low-temperature CO pulse chemisorption or temperature-programmed desorption can quantify surface adsorption sites [19].

- Nitrite-stripping Voltammetry: An electrochemical method that quantifies the charge from the reduction of nitrosyl ligands formed on active sites [18].

- Spectroscopic Techniques: Mössbauer spectroscopy can identify and quantify bulk iron species in Fe-N-C catalysts [19].

Q4: What is Turnover Frequency (TOF) and why is it a better metric than overall reaction rate?

The overall reaction rate (e.g., in mA/cm²_geo) depends on both the intrinsic activity of each active site and the total number of sites. Turnover Frequency (TOF) is defined as the number of reactant molecules converted per active site per unit time. It is a measure of the intrinsic activity of a catalytic site, independent of the total number of sites. This allows for a direct comparison of the fundamental performance of different catalytic materials. TOF is calculated as TOF = Overall Reaction Rate / Active Site Density [18].

Q5: How does pore structure optimization enhance catalytic activity?

Optimizing the pore structure, particularly by creating a highly interconnected macroporous network, enhances molecular diffusion and convective mass transfer of reactants. This ensures that the high internal surface area of a catalyst particle is fully utilized. Studies on porous TWC particles have shown that particles with an interconnected pore structure, thin framework walls, and high macroporosity exhibit superior CO oxidation performance because gaseous reactants can easily penetrate and utilize the internal active sites [13].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Poor correlation between measured surface area (BET) and catalytic activity.

- Potential Cause 1: The BET method measures the total surface area accessible to gas molecules (N₂) under vacuum, which may not reflect the surface area wetted by and accessible to liquid electrolytes or larger reactant molecules in a real application [17] [18].

- Solution: Use electrochemical methods like double-layer capacitance (Cdl) to estimate the ECSA, which is the surface area relevant to the electrochemical environment [17].

- Potential Cause 2: A significant portion of the surface area is located in micropores that are inaccessible to reactants or are not catalytically active.

- Solution: Perform pore size distribution analysis and correlate macropore/mesopore volume with activity. Design catalysts with hierarchical pore structures to facilitate mass transport [13].

Problem: Low measured Turnover Frequency (TOF).

- Potential Cause 1: Inaccurate quantification of active site density (SD). If the SD is overestimated (e.g., by including inactive sites), the calculated TOF will be artificially low [18].

- Solution: Validate your site density quantification method. For novel catalysts, using multiple complementary techniques (e.g., chemisorption and a spectroscopic method) can provide more reliable SD values [19] [18].

- Potential Cause 2: The intrinsic activity of the active sites is low due to electronic or geometric factors.

- Solution: Focus on catalyst synthesis strategies that optimize the electronic structure of the active sites, such as doping with heteroatoms or creating bimetallic sites, which have been shown to enhance intrinsic activity and stability [19].

Problem: Catalyst performance degrades rapidly during stability testing.

- Potential Cause 1: Loss of active sites due to leaching, agglomeration, or poisoning.

- Solution: Use inductively coupled plasma (ICP) spectroscopy to check for leached metals in the electrolyte. Post-stability-test characterization (e.g., TEM, XPS) can identify agglomeration or chemical changes.

- Potential Cause 2: Carbon support corrosion, especially in high-potential electrochemical applications [19].

- Solution: Explore more stable support materials or graphitized carbons. Bimetallic catalysts have sometimes been shown to improve stability, possibly through synergistic effects that protect the active sites [19].

Table 1: Common Electrochemical Methods for Active Surface Area and Site Density Estimation

| Method | Applicable Catalysts | Key Principle | Representative Conversion Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| HUPD [17] | Pt, Pt-alloys, Ru, Ir | Charge from adsorption/desorption of a monolayer of hydrogen atoms. | ECSA = Q_H / (0.21 mC cm⁻²) |

| CO Stripping [17] | Pt, Pd | Charge from oxidation of a pre-adsorbed monolayer of CO. | ECSA = Q_CO / (0.42 mC cm⁻²) |

| Double-Layer Capacitance (Cdl) [17] | Broadly applicable (metals, oxides, carbon) | Measurement of capacitive current in a non-Faradaic potential region at multiple scan rates. | ECSA = Cdl / Cs (C_s is specific capacitance) |

| Cyanide Probe [18] | Me-N-C SACs (Fe, Co, Mn, Ni), Pt-SAC | Spectrophotometric measurement of CN⁻ uptake correlated to loss of ORR activity. | SD = ( moles of CN⁻ adsorbed ) / ( mass of catalyst ) |

| CO Cryo Chemisorption [18] | Me-N-C (Fe, Mn) | Gas-phase CO adsorption at low temperatures (e.g., 193 K). | SD = ( moles of CO adsorbed ) / ( mass of catalyst ) |

Table 2: Turnover Frequencies of Selected Enzymes and Catalysts

| Catalyst / Enzyme | Reaction | Turnover Frequency (TOF) | Context / Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonic Anhydrase [20] | CO₂ + H₂O → HCO₃⁻ | 600,000 s⁻¹ | Exemplary high-activity biocatalyst. |

| Fe–N–C Catalyst [19] | Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR) | Quantified in study | TOF derived from combined Mössbauer spectroscopy and chemisorption data. |

| Catalase [20] | 2H₂O₂ → 2H₂O + O₂ | 93,000 s⁻¹ | Biocatalyst for peroxide decomposition. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Estimating ECSA via Double-Layer Capacitance (Cdl) using Cyclic Voltammetry

This is a widely used method for estimating the ECSA of various electrocatalysts [17].

- Electrode Preparation: Prepare a uniform working electrode with your catalyst material deposited on an inert substrate (e.g., glassy carbon).

- Electrolyte Selection: Choose an appropriate inert electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M KOH for base, 0.5 M H₂SO₄ for acid).

- Identify Non-Faradaic Region: Run a initial CV over a wide potential range to identify a window where no Faradaic (redox) reactions occur. A recommended starting point is 1.05–1.15 V vs. RHE [17].

- Multi-Scan Rate CV:

- In the selected non-Faradaic potential window, record CV curves at a series of scan rates (e.g., 5, 10, 20, 50, 100 mV s⁻¹).

- Ensure the CV curves are stable and symmetrical about the current-zero axis. If not, cycle the electrode until a stable capacitive current is obtained [17].

- Data Analysis:

- At a fixed potential (e.g., the middle of the scan window), plot the absolute value of the charging current (|ic|) against the scan rate (V).

- Fit the data to a linear regression. The slope of this line is equal to the double-layer capacitance (Cdl).

- ECSA Calculation:

- Calculate the ECSA using the formula: ECSA = Cdl / Cs, where C_s is the specific capacitance of a smooth standard surface of the same material. A typical value used for flat, standard surfaces is 20-60 µF cm⁻² [17].

Protocol 2: Quantifying Active Site Density in Fe–N–C Catalysts using the Cyanide Probe Method

This is an in situ method suitable for single-atom catalysts in electrolyte environments [18].

- Baseline ORR Activity:

- Measure the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) activity (e.g., via rotating disk electrode) of the Fe–N–C catalyst in an O₂-saturated electrolyte to establish a baseline performance.

- Cyanide Adsorption:

- Prepare an identical electrolyte but deaerated with N₂/Ar to remove O₂.

- Add a known, significantly high concentration of cyanide (CN⁻) to this deaerated electrolyte.

- Expose the catalyst to this CN⁻-containing solution for a sufficient time to allow for adsorption onto the Fe–Nₓ sites.

- CN⁻ Uptake Measurement:

- Use ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) spectrophotometry to measure the decrease in cyanide concentration in the solution. This is done by reacting the cyanide with a reagent like p-nitrobenzaldehyde to form a photoactive compound [18].

- The difference in CN⁻ concentration before and after adsorption gives the moles of CN⁻ irreversibly adsorbed on the active sites.

- Poisoned ORR Activity:

- After adsorption, thoroughly rinse the catalyst electrode to remove loosely bound CN⁻.

- Re-measure the ORR activity of the catalyst in a fresh, O₂-saturated electrolyte.

- Site Density (SD) Calculation:

- The moles of CN⁻ adsorbed is directly used to calculate the active site density: SD = (moles of CN⁻ adsorbed) / (mass of catalyst).

- The validity of the method is confirmed by the correlation between the amount of CN⁻ adsorbed and the relative decrease in ORR activity [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Catalytic Site Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Cyanide (KCN) [18] | Molecular probe for quantifying active site density in Me-N-C single-atom catalysts. | Highly toxic. Requires careful handling and disposal. Adsorption is performed in deaerated solutions to avoid competition with O₂. |

| Carbon Monoxide (CO) [19] [18] | Probe molecule for gas-phase chemisorption (low-temperature) to estimate site density. | Can be specific to certain metals (Fe, Mn). Requires thermal pre-treatment to clean catalyst surfaces, which may alter the material. |

| Anthraquinone-2-sulfonate (AQS) [21] | Redox-active probe molecule for electrochemical estimation of active site density on carbon-based catalysts. | Can be easily adsorbed and then removed from the electrode surface by potential cycling, allowing for reusable electrodes. |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) PMMA Template [13] | Sacrificial template for creating porous catalyst particles with controlled, interconnected pore structures. | Particle size and concentration in the precursor solution determine the final macroporosity and framework thickness of the catalyst. |

| Nafion Ionomer | Binder for preparing catalyst inks for electrochemical testing, providing proton conductivity. | The Nafion-to-catalyst ratio must be optimized, as too much can block active sites and pores, leading to underestimated activity [19]. |

Experimental and Conceptual Workflows

Diagram 1: Diagnostic Workflow for Catalyst Optimization. This flowchart outlines a systematic approach to deconvolute the factors limiting catalyst performance, guiding researchers from initial characterization to targeted synthesis improvements.

Diagram 2: Relationship Between Catalyst Structure and Activity. This diagram illustrates the logical chain connecting a catalyst's physical structure to its final performance, highlighting that high geometric surface area must be paired with good pore interconnectivity to be effective.

Pore Size Classification and Fundamental Concepts

What is the standard classification for pore sizes?

The most widely recognized classification system is defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), which categorizes pores based on their internal width or diameter [22]:

- Micropores: < 2 nm

- Mesopores: 2 nm - 50 nm

- Macropores: ≥ 50 nm

How does pore size distribution impact catalytic performance?

Pore size distribution describes the range and volume filled by different pore sizes within a material. This parameter is critical to catalytic performance because it influences:

- Surface area: Smaller pores increase surface area, boosting reaction sites and rates [23]

- Mass transfer efficiency: Pore networks govern the movement of reactants and products [23]

- Diffusion limitations: Smaller pores can slow analyses by limiting diffusion [23]

- Active site accessibility: Pores serve as conduits for transport to active sites [22]

Optimal Pore Size Ranges for Specific Reactions

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Optimal Pore Sizes for Various Catalytic Reactions

| Reaction Type | Catalyst Material | Optimal Pore Size Range | Key Performance Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-Butyl Levulinate Synthesis | Acid ion exchange resins | Enhanced mass transfer with macropores | Superior catalytic performance achieved with enhanced mass transfer properties [24] | |

| Electrochemical CO₂ Reduction | Porous Ag electrodes | 300-400 nm | Intrinsic CO production increases from ~100 nm to ~300 nm; plateaus above ~300 nm [25] | |

| Hydrodenitrogenation (HDN) | Mo sulfide-based catalysts | 6-18 nm | Appropriate pore diameter range identified for HDN process [26] | |

| Esterification Reactions | Hierarchically porous catalysts | Macropores introduced via templating | Achieved rapid esterification due to superior mass transfer performance [24] |

Research Reagent Solutions for Pore Structure Analysis

Table 2: Essential Materials and Methods for Pore Structure Characterization

| Technique | Measurement Range | Best For | Key Reagents/Equipment | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas Physisorption | 0.3-50 nm (Micropores to Mesopores) | High surface area powders, MOFs, zeolites [23] | N₂, Ar, CO₂; Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH), Density Functional Theory (DFT) models [23] | Measures gas adsorbed at different pressures to derive pore size distribution [23] |

| Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry (MIP) | 3 nm-1000 μm (Mesopores to Macropores) | Broad distributions including large pores; rigid solids [23] | Mercury, Washburn equation [22] | Mercury forced into pores under pressure; pore size inferred from intrusion volume [22] |

| Synchrotron CT | 1.48 nm-365 μm (Full scale) | Complex pore networks, 3D structural analysis [22] | Synchrotron radiation, 3D reconstruction algorithms | Non-destructive 3D imaging of internal pore structure [22] |

| FIB-SEM | Nanometers to hundreds of nanometers | Quantitative 3D porosity analysis, pore connectivity [25] | Ga⁺ ion source, SEM, 3D watershed algorithms | Serial sectioning for 3D reconstruction of pore networks [25] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Why do my catalyst performance results disagree with pore size measurements from a single technique?

This common issue often stems from technique-specific limitations and complex pore geometry effects [22]:

- Ink-bottle effect: MIP tends to measure pore throat dimensions rather than the actual pore body, potentially misclassifying volume in complex geometries [22]

- Isolated pores: Fluid invasion methods (MIP, gas adsorption) cannot effectively probe isolated, dead-end pores within the material [22]

- Method-specific ranges: Each technique has optimal measurement ranges, potentially missing critical pore size regimes [23]

Solution: Implement a multiscale multi-technique approach as demonstrated in Ni-Fe catalyst studies, which integrated synchrotron multiscale CT, MIP, and nitrogen adsorption to achieve comprehensive analysis across 1.48 nm to 365 μm [22].

How can I overcome diffusion limitations in mesoporous catalysts for liquid-phase reactions?

For esterification reactions like n-butyl levulinate synthesis, research indicates that enhancing mass transfer performance through pore structure regulation is a viable approach [24]:

- Traditional limitation: Experimental adjustment through trial-and-error is labor-intensive and lacks direction

- Simulation-guided solution: Use lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) numerical simulation to identify key pore structure parameters for optimal mass transfer before synthesis [24]

- Advanced templating: Employ MOFs (e.g., UiO-66) as sacrificial templates during suspension polymerization to achieve precise pore structure control matching simulation predictions [24]

What causes the "optimal pore size" phenomenon in electrochemical CO₂ reduction?

For porous Ag electrodes in CO₂ reduction, intrinsic CO production increases with pore diameter up to ~300 nm, then plateaus [25]. FIB-SEM analysis reveals this results from competing factors:

- Smaller pores (<200 nm): Higher tortuosity (up to 2.41) creates longer pore networks, causing additional potential drops that lower the effective driving force [25]

- Larger pores (>300 nm): Reduced tortuosity minimizes potential drop, but may reduce available surface area

- Balance point: ~300 nm pores provide optimal balance between sufficient surface area and minimal transport limitations [25]

Experimental Protocol: Template-Based Pore Structure Control

Principle: Use polymer sphere templates to create well-defined model catalysts for understanding pore size effects.

Workflow:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

PMMA Sphere Synthesis (Template Preparation)

- Prepare methyl methacrylate (MMA, Sigma Aldrich, >99%) in MilliQ water

- Vary MMA concentration (0.5 M to 1.9 M), stirring rate (450-600 rpm), and reaction temperature (70°C or 80°C) to control sphere diameter [25]

- Characterize sphere size distribution using ImageJ analysis of SEM images; ensure polydispersity index <0.04 for monodisperse distribution [25]

Template Formation

- Dry PMMA sphere suspensions on carbon paper (Toray TGP-H-060) on heating plate at 80°C [25]

- Verify ordered template structure via SEM before proceeding

Electrodeposition of Ag

- Prepare electrodeposition solution: 0.05 M AgNO₃ (Alfa Aesar, 99.9+%), 0.5 M NH₄OH (Emsure, 28-30%), 1.0 M NaNO₃ (Alfa Aesar, 99.0%), and 0.01 M EDTA (Sigma Aldrich, 98-103%) [25]

- Use three-electrode setup: Pt anode, 3 M Ag/AgCl reference, glassy carbon disc with PMMA electrode as cathode

- Apply potential of -0.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl until total charge of 2 C cm⁻² passes [25]

- Rinse with MilliQ water and air dry

Template Removal

- Soak electrode in ~10 mL acetone for ≥1 hour to remove PMMA template [25]

- Dry in air to obtain final porous Ag electrode

Characterization: Use FIB-SEM for quantitative 3D porosity analysis and pore connectivity assessment [25]

Principle: Utilize inherent structural collapse of MOFs in strong acid environments to create precisely controlled pore architectures during resin sulfonation.

Procedure:

- Incorporate UiO-66 (zirconium-based MOF) during suspension polymerization

- Leverage π-π interactions between MOF organic ligands and monomers

- Remove MOF template during sulfonation process via acid-induced structural collapse

- Achieve pore structures matching LBM numerical simulation predictions

Advantage: Overcomes limitations of traditional porogen methods, enabling precise match to simulation-optimized pore structures for enhanced mass transfer [24].

The Impact of Interconnected Pore Networks on Reactant Flow and Utilization

## FAQs: Pore Network Fundamentals

1. What is the primary role of an interconnected pore network in a catalyst? The primary role is to enhance mass transfer efficiency and accessibility to active sites, thereby increasing reaction rates and product yields. A well-designed pore network ensures that reactant molecules can easily travel to, and product molecules can escape from, the catalytic active sites. For example, in electrified CO2 capture and conversion systems, a 3D interconnected nanopore network was crucial for confining and enriching in-situ generated CO2, preventing it from escaping and significantly boosting conversion efficiency at high current densities [27].

2. How does pore size distribution affect catalytic performance? Pore size distribution directly influences which reactant molecules can access the catalyst's interior and how quickly they can move through it. The classification is:

- Micropores ( < 2 nm): Provide high surface area for reactions but can be prone to clogging.

- Mesopores (2-50 nm): Efficiently facilitate mass transfer for many molecular reactions.

- Macropores ( ≥ 50 nm): Act as transport arteries to the interior of catalyst particles.

An optimal catalyst often features a hierarchical structure combining these types. For instance, a study on Ni single-atom catalysts found that a structure combining multidirectional diffusion with <2 nm nanopores was far more effective at retaining reactant CO2 than those with only larger mesopores [27]. Multiscale characterization of Ni-Fe catalysts highlights that understanding the full pore size spectrum from nanometers to micrometers is critical for performance [22].

3. What are common experimental techniques for characterizing pore networks? No single technique can fully characterize the complex, multi-scale nature of pore networks. A combination is required [28] [22]:

| Technique | Typical Pore Size Range | Key Information Provided |

|---|---|---|

| Gas (N2) Physisorption | 0.4 - ~200 nm | Specific surface area, micro/mesopore volume and distribution [22]. |

| Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry (MIP) | ~3 nm - 800 μm | Meso/macropore volume and distribution, interconnectivity [22]. |

| Synchrotron X-ray CT | ~50 nm - hundreds of μm | 3D non-destructive visualization and quantification of pore space, connectivity, and complex geometries (e.g., "ink-bottle" pores) [22]. |

4. What is the difference between "Directional" and "Isotropic" pore networks? This distinction refers to the geometric arrangement of pores:

- Directional Pore Networks: Feature pores with a preferred orientation (e.g., unidirectional channels). These can facilitate fast flow in one direction but may be inefficient if reactants need to access sites from different angles [27].

- Isotropic Pore Networks: Feature pores with no directional preference, providing multidirectional pathways for reactants. This can lead to better overall distribution and utilization of active sites, especially in flooded environments or with viscous reactants [27]. Research on carbonate electrolysis showed that isotropic networks with nanopores outperformed directional mesoporous networks [27].

## Troubleshooting Guides

### Problem 1: Poor Product Yield Despite High Catalyst Activity

Symptoms: The catalyst shows high intrinsic activity in initial tests, but the overall product yield or Faradaic efficiency drops significantly at higher current densities or flow rates.

Possible Cause: Mass Transfer Limitations. Reactants cannot reach, or products cannot leave, the active sites fast enough. The pore network may be dominated by small, poorly connected pores that create diffusion barriers.

Solutions:

- Rethink Pore Architecture: Redesign the catalyst to have a hierarchical or isotropic pore structure. For example, consider introducing macropores as transport highways to feed mesopores and micropores where reactions occur.

- Increase Macropore Content: As demonstrated in resin catalyst development, introducing macropores can significantly enhance the internal mass transfer performance, leading to higher conversion rates [24].

- Verify with Simulation: Use pore-network modeling (e.g., PoreFlow) or Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM) simulations to predict mass transfer coefficients and identify optimal pore structure parameters (e.g., porosity, pore size ratios) before embarking on complex synthetic procedures [24] [28] [29].

### Problem 2: Rapid Catalyst Deactivation

Symptoms: Catalyst performance (activity/selectivity) declines quickly over time.

Possible Cause: Pore Blockage. This can be caused by coke formation, precipitation of side products, or physical clogging from large molecules in the feedstock. "Ink-bottle" pores (large cavities accessible only through narrow necks) are particularly susceptible [22].

Solutions:

- Characterize Pore Geometry: Use a combination of MIP and Synchrotron CT to identify the presence of ink-bottle pores and other problematic geometries [22].

- Minimize Tortuosity: Design pore networks with higher connectivity and lower tortuosity to facilitate the removal of condensable products or coke precursors before they block pores.

- Optimize Pore Size for Reaction: For reactions involving large molecules, such as polymer cracking, ensure the average pore size is sufficiently large to allow entry and exit. Interestingly, for polypropylene cracking, small catalyst particle size and high external acidity were more critical than internal mesopore size [30].

### Problem 3: Inconsistent Results Between Characterization Techniques

Symptoms: MIP and gas adsorption analysis provide conflicting data about the pore size distribution or total porosity.

Possible Cause: Technique-Specific Limitations. MIP can underestimate the presence of "ink-bottle" pores by only measuring the narrow entry necks. Gas adsorption may not accurately characterize large macropores.

Solutions:

- Adopt a Multimodal Approach: Correlate data from multiple techniques. Use gas adsorption for micro/mesopores, MIP for meso/macropores, and synchrotron CT for direct 3D visualization and to resolve discrepancies [22].

- Leverage 3D Imaging: CT scanning can directly reveal complex structural features like cavity structures and distinguish between connected and isolated pores, providing a ground truth for interpreting other data [22].

Table 1: Performance of Ni Single-Atom Catalysts with Engineered Pore Structures in CO2 Electroreduction [27]

| Catalyst Type | Key Pore Structure Features | Average Pore Diameter | Faradaic Efficiency to CO (FECO) at 300 mA/cm² |

|---|---|---|---|

| DirectionalMeso | Unidirectional channels, linear array | ~15 nm | Declined to below 30% |

| IsotropicMeso | Multidirectional mesopores | 2-50 nm | Below 35% |

| IsotropicNano | Multidirectional with <2 nm nanopores |

~3 nm | 50% ± 3% |

Table 2: Pore Network Modeling and Simulation Tools [24] [28] [29]

| Tool/Method | Primary Application | Key Advantage | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pore Network Models (PNM) | Simulating multi-phase flow, reactive transport, and constitutive properties. | Computationally efficient for studying meso-scale phenomena and upscaling. | Predicting relative permeability and saturation relationships [28] [29]. |

| Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM) | Simulating fluid flow and mass transfer in complex pore geometries. | Handles complex boundaries effectively; high parallel efficiency. | Optimizing mass transfer performance in resin catalysts for esterification [24]. |

| COMSOL "Reacting Flow in Porous Media" | Modeling heterogeneous catalysis with coupled fluid dynamics and chemical reactions. | User-friendly multiphysics interface for designing reactor geometry. | Analyzing species mixing and injection needle placement in a porous reactor [31]. |

## Experimental Protocols

Objective: To create a catalyst with a defined pore structure (DirectionalMeso, IsotropicMeso, or IsotropicNano) for enhanced reactive capture of CO2.

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Silica Templates: To define the pore channel topology and diameter.

- Nickel Precursor (Ni²⁺): The metal source for active sites.

- Ethylenediamine and Carbon Tetrachloride: Coordination and polymerization agents.

- NH₃ (gas): For post-synthesis treatment to modify surface properties.

Workflow:

- Coordination: Coordinate Ni²⁺ with ethylenediamine in solution.

- Polymerization: Polymerize the complex with carbon tetrachloride within the nanoconfined spaces of a selected silica template.

- Carbonization: Heat the composite under inert atmosphere to form a nitrogen-doped carbon matrix with atomically dispersed Ni.

- Template Removal: Etch away the silica template using HF or NaOH, leaving behind a porous carbon structure with the inverse morphology of the template.

- Integration: Airbrush the catalyst powder onto a hydrophilic carbon paper substrate to create the gas diffusion electrode.

Objective: To obtain a comprehensive, full-scale analysis of a catalyst's pore network, spanning nanometers to hundreds of micrometers.

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Liquid Nitrogen: Required for N₂ adsorption analysis at -196°C.

- High-Purity Mercury: The intrusive fluid for Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry (MIP).

- Capillary Tubes: For mounting samples for synchrotron CT.

Workflow:

- N₂ Physisorption:

- Degas: Pre-treat the catalyst sample under vacuum at 150°C to remove moisture and contaminants.

- Analyze: Measure the volume of N₂ gas adsorbed onto the catalyst surface at various pressures at -196°C.

- Calculate: Use models (e.g., BET for surface area, BJH for pore size) to determine micro/mesopore characteristics.

- Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry (MIP):

- Intrude: Place the sample in a penetrometer and incrementally increase mercury pressure, forcing it into the pores.

- Measure: Record the volume of mercury intruded at each pressure step.

- Calculate: Apply the Washburn equation to convert pressure data to pore size distribution, primarily for meso- and macropores.

- Synchrotron X-ray Computed Tomography (CT):

- Mount: Pack catalyst particles into a thin capillary tube.

- Image: Rotate the sample under a high-flux, high-coherence synchrotron X-ray beam, collecting projection images from multiple angles.

- Reconstruct: Use computational methods to reconstruct a 3D volumetric image of the catalyst's internal structure.

- Quantify: Apply image analysis to calculate porosity, pore connectivity, pore size distribution, and identify specific features like "ink-bottle" pores.

## Visualizations

### Pore Network Optimization Workflow

### The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents for Pore-Structured Catalyst Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| Silica Nanosphere Templates | Acts as a sacrificial solid template to create ordered mesopores and macropores with controlled size and geometry. | Creating DirectionalMeso, IsotropicMeso, and IsotropicNano Ni-SAC catalysts [27]. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) e.g., UiO-66 | Used as a nano-template that can be easily removed during acid treatment (sulfonation) to create hierarchical pores in polymer-based catalysts. | Preparing high-performance resin catalysts for esterification reactions [24]. |

| Crosslinker (Divinylbenzene) & Porogen | Forms the rigid polymer skeleton and creates pores during suspension polymerization of resin catalysts. The amounts determine pore structure. | Synthesizing resin catalysts (DmHn-SO3H) with tunable mass transfer properties [24]. |

| High-Purity Mercury & Liquid Nitrogen | Essential for pore structure characterization via MIP and N₂ physisorption, respectively. | Determining the full-scale pore size distribution of Ni-Fe industrial catalysts [22]. |

Advanced Synthesis and Engineering Techniques for Pore Structure Control

Template-Assisted Methods for Designing Ordered and Hierarchical Pores

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between hard and soft templating methods?

Hard templating, or nanocasting, uses rigid solid materials (e.g., silica, polystyrene spheres, anodic aluminum oxide) as a mold. The precursor material infiltrates the template's pores, and after solidification, the template is removed via chemical etching or calcination, leaving a replica of its structure [32] [33]. This method excels at creating precisely defined, highly ordered porous structures.

In contrast, soft templating employs non-rigid, molecular assemblies (e.g., block copolymers, surfactants, micelles) as structure-directing agents. These templates co-assemble with the precursor material and are typically removed during calcination [34] [32]. Soft templates are advantageous for creating materials with tunable mesopores but may offer less long-range order than hard templates.

FAQ 2: Why is creating hierarchically ordered pores (macro-, meso-, micro-) important for catalyst performance?

Hierarchical pore structures enhance catalytic performance by fulfilling multiple roles simultaneously:

- Micropores (< 2 nm) provide a high specific surface area, maximizing the density of exposed active sites [35].

- Mesopores (2–50 nm) facilitate efficient mass transport of reactants and products to and from the active sites, reducing diffusion limitations [35] [36].

- Macropores (> 50 nm) function as transport highways, allowing bulky molecules or particles (like soot) to access the catalyst's interior and further improving flow kinetics [37] [36].

This synergy results in superior activity, selectivity, and stability, as demonstrated in applications from oxygen reduction reactions to soot oxidation [35] [36].

FAQ 3: My porous structure collapses after template removal. What could be the cause?

Pore collapse is often linked to insufficient mechanical strength of the precursor framework during template removal. To mitigate this:

- Strengthen the Framework: Ensure complete precursor condensation/polymerization before template removal. For carbon-based materials, optimizing the pyrolysis temperature can enhance graphitization and mechanical stability [37].

- Use a Robust Template: Hard templates with interconnected 3D pore networks (e.g., KIT-6 silica) provide better structural support during replication than isolated pore systems [35].

- Gentle Removal: For hard templates, use a controlled etching process. For soft templates, a slow, programmed calcination rate helps prevent structural damage from rapid gas evolution [33].

FAQ 4: How can I control the coordination environment of single-atom sites using templating?

The local coordination of metal single-atoms can be engineered using specialized templates. For instance, using NaCl as a template allows for precise coordination control:

- At lower pyrolysis temperatures, the NaCl crystal lattice confines metal precursors, favoring symmetric M–N₄ coordination [38].

- At temperatures above NaCl's melting point (900 °C), the dissociated Cl⁻ ions can coordinate with the metal atom, creating asymmetric M–N₄–Cl sites [38]. This method provides a powerful tool for tailoring active sites at the atomic level for specific catalytic reactions.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Incomplete Template Filling or Non-Uniform Replication

Issue: The precursor does not fully infiltrate the template's pores, leading to fragmented or incomplete porous structures in the final material.

Solutions:

- Precursor Solution Optimization: Reduce the viscosity of the precursor solution by adjusting the solvent ratio. This improves its wettability and capillary force-driven infiltration into the template pores [35].

- Advanced Infiltration Techniques: Employ incipient wetness impregnation, which carefully matches the precursor solution volume to the total pore volume of the template. For better infiltration, use repeated vacuum-and-backfilling cycles during the impregnation process [35].

- Enhanced Diffusion: Allow extended contact time between the precursor and template (e.g., 24-48 hours) with gentle stirring to facilitate complete diffusion without inducing premature phase separation [37].

Problem: Poor Mass Transfer and Accessibility of Active Sites

Issue: The catalyst has a high surface area but exhibits low activity, indicating that reactants cannot efficiently reach the active sites, often due to a lack of interconnected larger pores.

Solutions:

- Design Hierarchical Porosity: Integrate multiple template types. For example, use polystyrene (PS) spheres to create macropores and a soft template (e.g., F127) to create mesopores simultaneously. The PS burns out during pyrolysis, creating large channels, while the soft template generates the mesoporous walls [37] [36].

- Use 3D Interconnected Templates: Select hard templates like KIT-6 silica or 3DOMM-CZO, which possess 3D bicontinuous pore networks that replicate into highly interconnected catalyst frameworks, drastically improving mass flow [35] [36].

- Verify Pore Interconnectivity: Use techniques like electron tomography and pore size distribution analysis from N₂ sorption to confirm that pores are interconnected rather than isolated [35].

Problem: Metal Aggregation and Loss of Single-Site Dispersion During Synthesis

Issue: Instead of forming isolated single-atom sites, metal precursors aggregate into nanoparticles during pyrolysis, reducing catalytic efficiency.

Solutions:

- Spatial Confinement with Rigid Templates: Use a rigid template (e.g., NaCl crystals, mesoporous silica) to physically separate and confine metal atoms during high-temperature treatment. The template's lattice structure prevents metal migration and aggregation [38].

- Optimize Pyrolysis Conditions: Implement a controlled heating ramp and use an inert atmosphere. The presence of a carbon/nitrogen precursor (e.g., dicyandiamide) during pyrolysis can help trap metal atoms in developing N-doped carbon sites, stabilizing them as M–Nₓ [38].

- Employ a Multi-Step Process: As demonstrated in the soft spray technique, first assemble the organic ligand and metal ion in separate solutions, then combine them via spray onto the template. This minimizes uncontrolled pre-aggregation before the structured assembly occurs [39].

The following tables consolidate key performance data from recent studies on template-synthesized porous materials for catalytic applications.

Table 1: Performance of Hard-Templated Fe-N-C Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR)

| Catalyst | Silica Template | Pore Architecture | Onset Potential (V vs. RHE) | Half-wave Potential (V vs. RHE) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe–N@CMK-3 [35] | SBA-15 | 2D Hexagonal Mesopores | 0.99 (Alkaline) | — | Well-defined mesopores enhance O₂ diffusion, leading to highest activity. |

| Fe–N@CMK-3 [35] | SBA-15 | 2D Hexagonal Mesopores | 0.82 (Acid) | — | Well-defined mesopores enhance O₂ diffusion, leading to highest activity. |

| Fe–N@CMK-8 [35] | KIT-6 | 3D Cubic Micropores | Lower than CMK-3 | — | Limited oxygen accessibility in microporous network reduces activity. |

| Fe–N@CMK-3/8 [35] | SBA-15/KIT-6 | Combined Micro/Mesopores | Intermediate | — | Balanced performance and sustained 4e⁻ pathway in stability tests. |

Table 2: Performance of Template-Assisted Catalysts in Energy and Environmental Applications

| Catalyst | Template Used | Application | Key Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3DOH-Co@NC [37] | PS Spheres | Lithium-Oxygen Batteries | Discharge Specific Capacity | 28,000 mA h g⁻¹ |

| RuPd/3DOMM-CZO [36] | PMMA (Macro) & F127 (Meso) | Simultaneous Soot & CH₄ Oxidation | T₅₀ (Soot Oxidation) | 385 °C |

| RuPd/3DOMM-CZO [36] | PMMA (Macro) & F127 (Meso) | Simultaneous Soot & CH₄ Oxidation | T₅₀ (CH₄ Oxidation) | 465 °C |

| Fe1CNCl (SAC) [38] | NaCl | Peroxymonosulfate Activation | Substrate Degradation | >90% (in 30 min) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Hierarchical ZIF-8 Membrane via Soft Spray and PS Template

This protocol describes the synthesis of a hierarchically ordered pore ZIF-8 membrane using polystyrene (PS) latex as a hard template and soft spray technology [39].

Workflow Diagram: HP ZIF-8 Membrane Fabrication

Materials and Instrumentation:

- Polystyrene (PS) Latex Dispersion (particle size: 400 nm) [39]: Serves as the sacrificial hard template to create macropores.

- Zinc Acetate Anhydrous (Zinc source) [39].

- 2-Methylimidazole (Organic ligand) [39].

- Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) (optional, for forming a mixed matrix membrane) [39].

- Soft Spray Apparatus: Consists of a spray nozzle and solution delivery system.

- Langmuir-Blodgett Trough: For assembling the PS template at the air-water interface.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- PS Template Assembly: Add the PS latex dispersion dropwise to the surface of pure water in a Langmuir-Blodgett trough. The PS spheres will self-assemble into an ordered monolayer at the air-water interface, indicated by the appearance of rainbow colors [39].

- Ligand Introduction: Carefully add a specific amount of 2-methylimidazole solution into the water subphase beneath the PS template. If fabricating a mixed matrix membrane, dissolve PVA in this solution beforehand [39].

- Metal Spray and Membrane Formation: Spray a solution containing zinc ions (from zinc acetate) onto the interface using the soft spray apparatus. This technique minimizes disturbance to the assembled PS template. As spraying proceeds, the ZIF-8 crystal network forms around the PS spheres, generating a ZIF-8/PS composite membrane at the interface [39].

- Template Removal and Collection: Transfer the composite membrane to a solvent (e.g., tetrahydrofuran) that selectively dissolves the PS spheres. This step removes the template, leaving behind the hierarchically porous ZIF-8 membrane [39].

- Characterization: Characterize the final membrane using techniques like scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to confirm the ordered macroporous structure and X-ray diffraction (XRD) to verify ZIF-8 crystallinity [39].

Protocol 2: Synthesis of 3D Ordered Hierarchical Co@N-Doped Porous Carbon (3DOH-Co@NC) Using PS Spheres

This protocol uses PS spheres as a sacrificial template to create a 3D ordered macroporous structure from a ZnCo-ZIF precursor for application in lithium-oxygen batteries [37].

Workflow Diagram: 3DOH-Co@NC Synthesis

Materials and Instrumentation:

- Styrene, Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) [37]: For synthesizing monodisperse PS spheres.

- Zinc Nitrate Hexahydrate & Cobalt Nitrate Hexahydrate: Metal sources for the bimetallic ZIF.

- 2-Methylimidazole: Organic ligand for ZIF formation.

- Ammonia Solution: Used to promote crystallization.

- Tube Furnace: For pyrolysis under an inert gas atmosphere.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- PS Array Synthesis: Synthesize PS spheres via emulsion polymerization. In a reflux system under nitrogen at 85°C, polymerize styrene in water using SDS as a surfactant. This produces a close-packed array of PS spheres [37].

- ZIF Precursor Infiltration: Immerse the PS template in a methanol solution containing cobalt nitrate, zinc nitrate, and 2-methylimidazole. This allows the metal and ligand precursors to infiltrate the voids between the PS spheres [37].

- Crystallization: Transfer the infiltrated template into a mixture of methanol and ammonia to induce the crystallization of ZnCo-ZIF around the PS spheres, forming a ZnCo-ZIF@PS composite [37].

- Pyrolysis and Template Removal: Place the composite in a tube furnace and pyrolyze at 800°C for 2 hours under a nitrogen atmosphere. During this step, the PS template volatilizes, creating the macroporous structure, while the ZnCo-ZIF simultaneously converts into a N-doped carbon framework with embedded cobalt nanoparticles [37].

- Characterization: Use techniques like transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to observe the 3D ordered porous structure and the distribution of Co nanoparticles, and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) to analyze the surface chemical composition [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Template-Assisted Synthesis of Porous Materials

| Reagent/Template | Function | Key Characteristics & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Hard Templates | ||

| Mesoporous Silica (SBA-15, KIT-6) [35] | Creates ordered mesoporous carbons and metal oxides via nanocasting. | SBA-15: 2D hexagonal pores (p6mm). KIT-6: 3D bicontinuous cubic architecture (Ia3d). Removed by HF or NaOH etching. |

| Polystyrene (PS) Spheres [39] [37] | Sacrificial template for 3D ordered macroporous (inverse opal) structures. | Available in highly monodisperse sizes. Removed by calcination or dissolution with THF, leaving behind a periodic macroporous network. |

| NaCl Crystals [38] | Green, recyclable template for 3D honeycomb-like morphologies in single-atom catalysts. | Low-cost, easily removed by washing with water. Its phase change (melting) can be used to tailor metal coordination environments (e.g., M–N₄ vs. M–N₄–Cl). |

| Soft Templates | ||

| Block Copolymers (Pluronic P123, F127) [35] [36] | Structure-directing agents for mesoporous silica and carbon. | Self-assemble into micelles in solution. The PPO/PEO blocks define the mesopore structure (e.g., 2D hex, 3D cubic). Removed during calcination. |

| Ionic Liquids & Surfactants [39] [32] | Soft templates for introducing meso- or macroporosity into MOFs and other materials. | Non-rigid, form dynamic assemblies. Offer tunable pore sizes but may provide less long-range order than hard templates. |

| Precursors | ||

| Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks (ZIFs) [39] [37] | Metal-organic frameworks used as self-sacrificing precursors for N-doped porous carbons. | Contain metal (e.g., Zn²⁺, Co²⁺) and organic imidazolate links. Upon pyrolysis, they form high-surface-area carbons with atomically dispersed metal sites. |

| 1,10-Phenanthroline & Dicyandiamide [35] [38] | Common nitrogen and carbon precursors. | Used in conjunction with metal salts to create M–N–C type catalysts. Dicyandiamide is often a primary N/C source, while 1,10-phenanthroline can chelate metals. |

Solvothermal Synthesis and the Role of Solvents in Pore Architecture

Troubleshooting Guide: Solvent-Related Issues in Solvothermal Synthesis

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when using solvothermal synthesis to control material pore architecture.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Solvent-Related Issues

| Problem Description | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Product Yield [40] | Incomplete reaction or precursor precipitation. | Optimize the mole ratio of metal precursor to organic linker; a higher ligand ratio (e.g., 1:8) can drive the reaction to completion [40]. |

| Low Surface Area or Porosity [40] [41] | Solvent or unreacted linker molecules trapped in pores. | Use solvents with low boiling points for easier removal; implement a sustained solvent exchange protocol with fresh solvent post-synthesis [40] [41]. |

| Poor Crystallinity [41] | Excessively fast nucleation, leading to many small, defective crystals. | Employ a modulating agent (e.g., acetic acid) to competitively slow down nucleation and promote slow, defect-free crystal growth [41]. |

| Formation of Undesired Crystal Phase or Polymorph [42] [43] | Solvent properties (polarity, viscosity) are mismatched for the target phase. | Systematically screen solvents (e.g., THF vs. DME) to find the one that stabilizes the desired polymorph, as solvent free energy of solvation can dictate the final structure [42] [43]. |

| Uncontrolled Crystal Morphology/Size [44] [41] | Inconsistent chemical environment during nucleation and crystal growth. | Utilize a Dynamic Solvent System (DSS), where a chemical reaction (e.g., esterification between 1-butanol and acetic acid) dynamically changes modulator concentration, allowing separate control over nucleation and growth phases [41]. |

| Use of Toxic Solvents (e.g., DMF) [41] | Standard protocols often rely on toxic, non-renewable solvents. | Replace toxic solvents with greener alternatives. For MOFs, a DSS of 1-butanol and acetic acid is effective and produces a value-added ester (butyl acetate) [41]. For ZIF-8, methanol or water-based methods can be used [40]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does the solvent choice fundamentally influence the pore architecture of my material? The solvent directly impacts pore structure by controlling crystallization kinetics and thermodynamics. It affects nucleation speed, crystal growth rate, and ultimately, the final material's surface area, pore size, and volume [41]. Computational studies show that solvents with different kinetic diameters and polarities stabilize frameworks to varying degrees, even influencing which polymorph is most stable [43].

Q2: What is the "Dynamic Solvent System" and how can it improve my synthesis? A Dynamic Solvent System (DSS) is a reactive solvent mixture where a chemical reaction, such as esterification, changes the composition and properties of the reaction medium over time [41]. This allows for high modulator concentration during the nucleation phase to limit nuclei formation, followed by a decrease in concentration to enable optimal crystal growth rates. This provides superior control over crystal size and morphology compared to static solvent systems [41].

Q3: Are there greener alternatives to common toxic solvents like DMF in MOF synthesis? Yes. A prominent green alternative is a mixture of 1-butanol and acetic acid, which acts as a DSS [41]. This system is non-toxic, can be derived from renewable resources, and produces a valuable ester byproduct (butyl acetate), contrasting with DMF, which decomposes into low-value compounds [41]. For some materials like ZIF-8, water or methanol can also be used as a primary solvent [40].

Q4: Why is my product's surface area lower than expected, and how can I improve it? Low surface area often results from residual species blocking the pores. This can be unreacted organic linkers or high-boiling-point solvents trapped within the pores [40]. To mitigate this, ensure proper purification through sustained washing and solvent exchange. Using solvents that are easily removed and optimizing reagent ratios to minimize unreacted precursors can significantly improve the final surface area [40] [41].

Q5: Can the solvent choice affect the crystal phase of my final product? Absolutely. The solvent can direct the synthesis toward specific crystalline phases. For instance, in synthesizing iron oxides, a high water/2-propanol ratio favored magnetite/maghemite, while a low ratio favored hematite [45]. Similarly, in SiOx synthesis, the choice between THF and DME led to materials with different electrochemical properties due to variations in stoichiometry [42].

Experimental Protocols for Pore Structure Optimization

This protocol uses a reactive solvent mixture to achieve superior control over crystal size and morphology, key factors in pore architecture.

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Metal Source: e.g., Ni(II) or Zn(II) salt.

- Organic Linker: e.g., 1,4-bis(1H-pyrazol-4-yl)benzene (H₂bdp).

- Dynamic Solvent System: A mixture of 1-Butanol (solvent and reactant) and Acetic Acid (modulator and reactant).

- Modulator: Acetic acid competes with the linker for metal sites, controlling deprotonation and nucleation.

Methodology:

- Dissolve the metal salt and organic linker in the DSS (1-butanol and acetic acid).

- Transfer the solution to a sealed solvothermal reactor (e.g., Teflon-lined autoclave).

- Heat the reactor to the target temperature (e.g., 120°C). The esterification reaction between 1-butanol and acetic acid will dynamically reduce the acetic acid concentration over time.

- Maintain the temperature for a specified duration (e.g., 24-72 hours).

- Cool the reactor to room temperature.

- Collect the product via centrifugation and wash thoroughly with fresh 1-butanol to remove any residual reactants and byproducts.

- Activate the MOF by removing the guest solvent molecules, typically under vacuum at elevated temperature, to open up the pore structure.

This protocol demonstrates how solvent composition can be used to select for specific material phases.

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Precursors: A mixture of Fe(II) and Fe(III) salts.

- Precipitating Agent: Sodium hydroxide (NaOH).

- Solvent System: A mixture of Water and 2-Propanol in varying volume ratios.

Methodology:

- Prepare a series of reaction mixtures with varying water/2-propanol volume ratios (e.g., from high to low water content).

- Add the mixture of Fe(II) and Fe(III) salts to the solvent system.

- Add the precipitating agent (NaOH) to the solution under stirring.

- Transfer the mixture to a solvothermal reactor and heat to 150°C for a set time.

- Characterize the products from each solvent condition using XRD and VSM. Expect a predominance of magnetite/maghemite at high water ratios and a shift toward hematite at low water ratios [45].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Solvothermal Synthesis Optimization

| Reagent | Function in Synthesis | Key Consideration for Pore Architecture |

|---|---|---|

| Dimethylformamide (DMF) | High-polarity solvent for dissolving diverse precursors. | Common but toxic; decomposes to low-value byproducts. Associated with reproducibility and environmental concerns [41]. |

| Methanol (MeOH) | Common solvent for room-temperature synthesis (e.g., of ZIF-8). | Easily dissolves precursors and can be removed readily, helping to achieve high surface areas [40]. |

| 1-Butanol / Acetic Acid (DSS) | Green, reactive solvent system and modulator. | The dynamic change in composition allows separate control over nucleation and growth, enabling precise morphology and size control [41]. |

| Water (H₂O) | Green, inexpensive solvent for aqueous-based synthesis. | A sustainable choice, though may require additives (e.g., triethylamine) to facilitate deprotonation of linkers [40]. |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) / 1,2-Dimethoxyethane (DME) | Aprotic solvents with different solvation abilities. | The choice can influence the material's final stoichiometry and electrochemical properties, as seen in SiOx synthesis [42]. |

| Modulators (e.g., Acetic Acid) | Monodentate ligands that compete with organic linkers. | Slow down nucleation and crystal growth, leading to larger crystals with fewer defects and potentially more ordered pore systems [41]. |

Visualization of Synthesis Pathways and Solvent Roles

Solvent Role in Pore Formation Pathway

Dynamic Solvent System Mechanism

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary relationship between a catalyst's pore structure and its surface area? The pore structure of a catalyst is intrinsically linked to its specific surface area. Optimizing the pore architecture—including parameters like porosity, pore size distribution, and the ratio of macropores to mesopores—directly enhances the available surface area for reactions and improves mass transfer efficiency. This allows reactants to better access the active sites within the catalyst particle, thereby improving the overall catalytic performance [24].