The d-Band Center Theory in Heterogeneous Catalysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Catalyst Design

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the d-band center theory, a foundational electronic descriptor in heterogeneous catalysis.

The d-Band Center Theory in Heterogeneous Catalysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Catalyst Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the d-band center theory, a foundational electronic descriptor in heterogeneous catalysis. Tailored for researchers and scientists, we detail the theory's core principles, its application in predicting catalyst activity for reactions like hydroformylation and water electrolysis, and advanced methodologies for its calculation and integration with machine learning. The content further addresses the theory's limitations, including its performance on magnetized surfaces and single-atom catalysts, and presents modern validation techniques that complement it with data-driven approaches. This guide synthesizes foundational knowledge with cutting-edge developments to empower the rational design of next-generation catalysts.

Unlocking Catalytic Activity: The Fundamentals of d-Band Center Theory

The pursuit of a unifying principle that can bridge the molecular-level understanding of homogeneous catalysts with the practical durability of heterogeneous systems represents a cornerstone of modern catalytic research. For decades, the field has been challenged by the absence of a common descriptor that transcends these categories. The d-band center theory has emerged as a powerful, transferable electronic descriptor that is reshaping this landscape, enabling the predictive design of catalysts from first principles and offering a cohesive framework for understanding catalytic activity across diverse reactions. [1] [2]

The d-band center theory, pioneered by Hammer and Nørskov, provides a critical link between the electronic structure of a transition metal catalyst and its surface reactivity. The theory posits that the mean energy of the d-band electron states, known as the d-band center (εd), dictates the strength of adsorbate binding on the catalyst surface. [2] [3]

A higher d-band center (closer to the Fermi level) strengthens the adsorption of reactive intermediates due to enhanced overlap and repulsion between the adsorbate's states and the metal's d-states. Conversely, a lower-lying d-band center results in weaker adsorption. This fundamental relationship creates a "volcano plot" dependence of catalytic activity on adsorption strength, formalized by the Sabatier principle: the optimal catalyst binds intermediates neither too strongly nor too weakly. [2] [4] By quantitatively adjusting the d-band center, researchers can precisely control adsorption energies to maximize catalytic activity. [5]

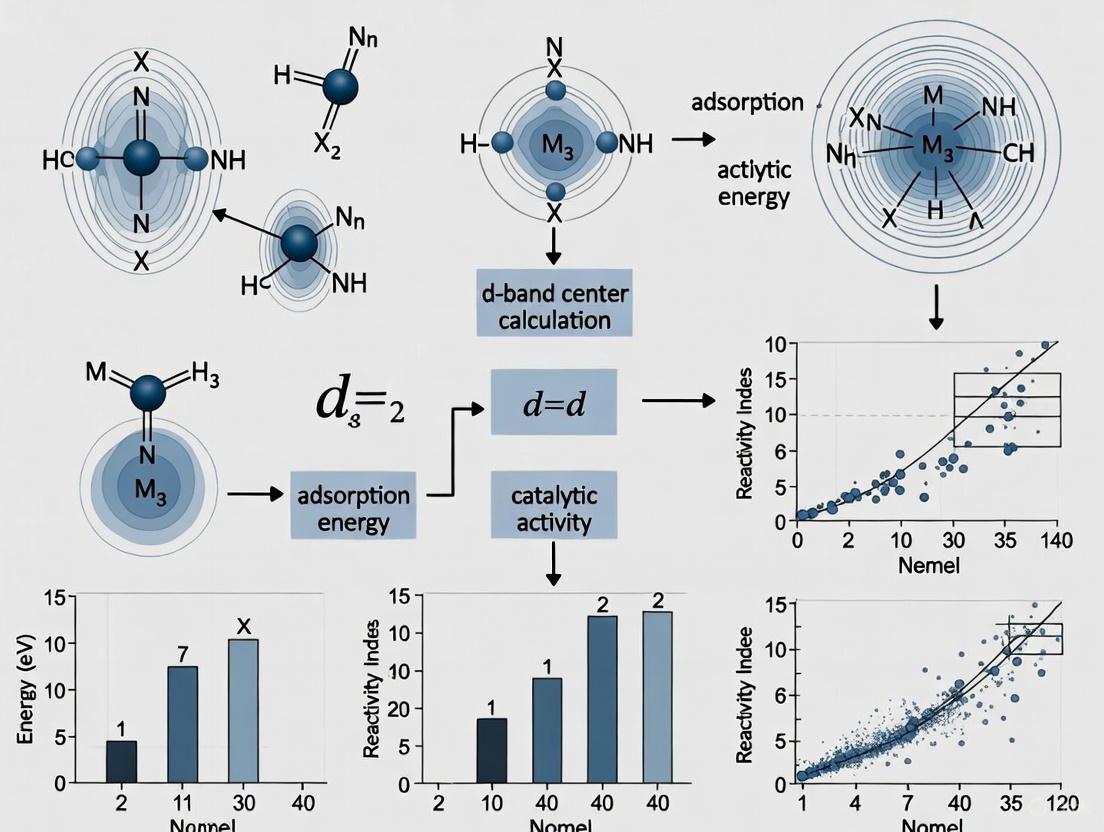

Diagram 1: The core principle of d-band center theory and its key influencing factors.

Quantitative Framework and Key Experimental Data

The predictive power of d-band center theory is demonstrated through quantitative correlations across various catalytic systems. The following table summarizes key experimental and computational findings that validate its role as a unifying descriptor.

Table 1: Quantitative Correlations of d-Band Center with Catalytic Performance

| Catalytic System | Reaction | Optimal d-Band Center (εd) | Key Performance Metric | Correlation (R²) | Reference/Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rh–P Nanoparticles | Hydroformylation | Aligned with homogeneous Rh-phosphine complex | Reaction Rate: 13,357 h⁻¹ (25% increase over state-of-art) | 0.994 | Computation-guided framework [1] |

| Mn-RuO₂ (MRO) Dual-Site Catalyst | Lithium-Sulfur Batteries (SRR/SER) | Complementary sites for HOMO/LUMO alignment | Balanced redox kinetics; superior cell performance under limited electrolyte | Dual d-band model | Extended d-band theory [6] |

| Fe-, Co-, Ni-based Electrocatalysts | Water Electrolysis (OER/HER) | Tailored via doping, vacancies, nanostructuring | Reduced overpotential; enhanced stability | Established descriptor | Review of iron-series metals [5] |

| Transition Metal Surfaces (Cu, Pt, Ni, etc.) | C1–C2 Species Thermochemistry | Position relative to Fermi level | Adsorption energy of intermediates | MAE comparable to DFT | Statistical learning model [3] |

Methodological Toolkit: Probing and Applying the d-Band Center

The rational design of catalysts using d-band center theory relies on a suite of computational and experimental techniques.

Core Computational and Experimental Characterization Methods

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Methods for d-Band Center Analysis

| Method/Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Key Insight Provided |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Computational Simulation | Calculates electronic structure and total energy of systems. | Provides absolute εd values and predicts adsorption energies. [1] [3] |

| Machine Learning (ML) | Data Analysis | Accelerates discovery and maps structure-property relationships. | Identifies promising catalyst compositions; reduces DFT load. [1] [7] [8] |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Experimental Characterization | Probes surface elemental composition and chemical state. | Validates surface chemistry and electronic environment. |

| Ultraviolet Photoelectron Spectroscopy (UPS) | Experimental Characterization | Measures the valence band structure. | Experimentally determines the d-band center position. |

| Transition Metal Precursors (e.g., Rh, Ru, Fe, Co, Ni salts) | Catalyst Synthesis | Serves as the source of the active metal component. | Forms the core catalytic site with tunable d-electron configuration. [1] [5] |

| Dopants / Alloying Elements (e.g., P, Mn, heteroatoms) | Catalyst Synthesis | Modifies the electronic structure of the host metal. | Shifts the εd via strain and ligand effects. [1] [2] [6] |

A Unified Workflow for Catalyst Design

The integration of these tools into a coherent workflow enables the targeted design of catalysts, as exemplified by the development of Rh₃P nanoparticles for hydroformylation. [1]

Diagram 2: The unified catalyst design workflow leveraging d-band center alignment.

Step 1: Electronic Structure Alignment. The process begins by using the d-band center as a transferable descriptor to align the electronic structure of a target heterogeneous system with that of a high-performance benchmark catalyst—in this case, a homogeneous Rh-phosphine complex. [1]

Step 2: High-Throughput Computational Screening. A compositional library of potential candidates (e.g., Rh-P phases) is screened using a workflow that integrates machine learning-accelerated molecular dynamics and DFT calculations. This step identifies the composition whose d-band center most closely matches the target. [1] [8]

Step 3: Experimental Validation and Performance Assessment. The top candidate from the screening process, Rh₃P, is synthesized and evaluated. The experimental result was a reaction rate of 13,357 h⁻¹, a 25% increase over the previously most active phase, confirming the predictive power of the d-band center alignment. [1]

Advanced Applications and Evolving Theories

The application of d-band center theory continues to expand and evolve, driven by new catalytic challenges.

- Decoupling Redox Kinetics: In lithium-sulfur batteries, the classical model has been extended to a "dual d-band model." This framework uses two distinct catalytic sites with complementary d-band centers: one aligned with the LUMO of sulfur species to optimize the sulfur reduction reaction (SRR), and another aligned with the HOMO to accelerate the sulfur evolution reaction (SER). This approach effectively balances complex redox kinetics. [6]

- Moving Beyond with Statistical Learning: While powerful, the d-band model is not exhaustive. Statistical learning approaches, such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA), applied to massive DFT thermochemical datasets have shown that adsorption energy is controlled by a combination of covalent (d-band center) and ionic terms (e.g., reduction potential), further modulated by conjugation and conformational effects. [3] This allows for the accurate prediction of vast reaction networks with a minimal number of DFT calculations.

- Generative AI for Catalyst Design: Generative machine learning models are now being applied to the inverse design problem—creating novel catalyst structures with desired properties from scratch. These models can propose new surface structures and adsorption site motifs, exploring chemical spaces far beyond human intuition. [8]

The d-band center theory has firmly established itself as a foundational and unifying principle in catalysis. It provides a quantifiable electronic descriptor that successfully bridges the traditional divide between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis, between thermal and electrochemical processes, and between fundamental surface science and applied reactor engineering. While advanced statistical learning and AI are revealing additional layers of complexity, the d-band center remains a cornerstone for the rational, predictive, and accelerated design of next-generation catalysts. Its continued evolution promises to further unify the field, guiding the quest for more efficient, selective, and sustainable chemical transformations.

In the field of heterogeneous catalysis, the d-band center theory stands as a foundational model for understanding and predicting the chemical reactivity of transition metal surfaces. Proposed by Professor Jens K. Nørskov and colleagues, this theory provides a powerful electronic descriptor that correlates the electronic structure of a catalyst with its adsorption properties and catalytic activity [2] [9]. The theory fundamentally addresses how the energy distribution of d-electron states in transition metals influences their interaction with adsorbate molecules, thereby governing key catalytic processes [2].

The core premise of d-band center theory lies in its ability to establish a direct connection between the position of the d-band center (εd) and the adsorption strength of reactants or intermediates on transition metal surfaces [10]. This relationship has proven indispensable in rational catalyst design, enabling researchers to systematically engineer materials with optimized catalytic performance for reactions ranging from water electrolysis to hydroformylation [1] [2]. The theory has been extensively generalized to a broad class of transition metal-based systems, including alloys, oxides, sulfides, and other complexes, making it a versatile tool across various catalytic applications [10].

Electronic Structure Fundamentals

Quantum Mechanical Origins

The electronic band structure of a solid describes the range of energy levels that electrons may occupy, derived from the quantum mechanical wave functions for electrons in a periodic lattice of atoms [11]. In transition metals, the formation of d-bands occurs when atoms approach each other to form a solid crystal structure. As N identical atoms come together, the atomic orbitals of each atom overlap with those of its neighbors [11].

Each discrete atomic d-orbital energy level splits into N closely spaced levels, forming a continuous energy band [11]. Since a macroscopic solid contains approximately 10²² atoms, the adjacent energy levels are so closely spaced (on the order of 10⁻²² eV) that they can be considered a continuum [11]. The d-band center represents the weighted average energy of these d-electron states relative to the Fermi level, mathematically defined as the first moment of the d-band density of states (DOS) [10].

The d-band center position is calculated using the formula: [ \epsilond = \frac{\int{-\infty}^{\infty} E \cdot \rhod(E) dE}{\int{-\infty}^{\infty} \rhod(E) dE} ] where (\rhod(E)) is the projected density of states (PDOS) for the d-orbitals [10]. This quantitative descriptor can be derived from Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations, providing a powerful parameter for predicting catalytic behavior.

D-Band Center and Adsorption Strength

The fundamental relationship between d-band center position and adsorption strength follows a systematic trend [10]:

- Higher d-band center (closer to the Fermi level): Stronger bonding interactions between d-orbitals and adsorbate s/p orbitals, leading to increased adsorption strength

- Lower d-band center (further below Fermi level): Weaker interactions due to increased population of anti-bonding states, resulting in reduced adsorption energies

This behavior is rooted in the principles of orbital hybridization and electronic filling, where the position of the d-band center relative to the Fermi level determines the filling of anti-bonding states formed during adsorption [10]. When the d-band center is closer to the Fermi level, the anti-bonding states shift upward, becoming less filled and thus strengthening the adsorbate-substrate bond [9].

Table 1: D-Band Center Correlation with Catalytic Properties

| D-Band Center Position | Adsorption Strength | Catalytic Activity Trend | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| High (close to Fermi level) | Strong | Enhanced for reactions requiring strong intermediate binding | Oxygen Evolution Reaction (OER) [2] |

| Medium (optimal range) | Moderate | Maximum activity (Sabatier principle) | Hydroformylation [1], Nitrogen Reduction [12] |

| Low (far from Fermi level) | Weak | Enhanced for reactions requiring facile desorption | Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER) [2] |

Computational Characterization Methods

Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations

Density Functional Theory serves as the primary computational method for determining the d-band center of catalytic materials. The standard workflow involves:

- Structure Optimization: Geometry optimization of the catalyst surface model using plane-wave DFT codes such as VASP [13]

- Electronic Structure Calculation: Self-consistent field calculation to obtain the converged electronic structure

- Projected Density of States (PDOS) Analysis: Projection of the total density of states onto the d-orbitals of the relevant transition metal atoms

- D-Band Center Calculation: Integration of the d-PDOS using the established formula to determine εd [10]

Standard DFT parameters typically include:

- Exchange-correlation functional: GGA-PBE (Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof) [13] [10]

- Plane-wave cutoff energy: 500 eV [13]

- k-point sampling: Monkhorst-Pack grid (e.g., 3×3×1 for surfaces) [13]

- Van der Waals correction: DFT-D3 method of Grimme [13]

- Pseudopotential: Projector Augmented Wave (PAW) method [13] [10]

For systems with strong electron correlations, such as those containing transition metal oxides, the DFT+U approach (incorporating Hubbard model corrections) may be employed to improve accuracy [10].

Workflow for D-Band Center Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive computational workflow for d-band center calculation and application in catalyst design:

Diagram 1: Computational workflow for d-band center analysis in catalyst design.

Advanced Machine Learning Approaches

Recent advances have integrated machine learning with d-band center theory to accelerate materials discovery. Deep generative models such as diffusion models have been developed for inverse materials design conditioned on target d-band center values [10]. For instance, the dBandDiff model generates novel crystal structures with specified d-band centers and space group symmetry, demonstrating that 72.8% of generated structures are geometrically and energetically reasonable based on high-throughput DFT validation [10].

Artificial neural networks (ANNs) have also been successfully trained using d-band features to predict catalytic activity. In screening bimetallic alloy catalysts for the nitrogen reduction reaction (NRR), ANNs achieved a mean absolute error of 0.23 eV for limiting potential predictions compared to DFT references [12].

Experimental Characterization Techniques

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS)

Experimental determination of d-band parameters presents significant challenges but can be achieved through synchrotron-based spectroscopic techniques. A recently developed methodology employs X-ray Absorption Near Edge Structure (XANES) fitting to accurately determine d-band width and d-band center positions in metallic nanoparticles [14].

The experimental protocol involves:

- Sample Preparation: Synthesis of well-defined transition metal nanoparticles (e.g., Pd NPs) with controlled size and composition

- XANES Measurements: Collection of high-resolution XANES spectra at the relevant absorption edges using synchrotron radiation

- Valence Band XPS: Complementary valence band X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (VBXPS) to calibrate the XANES spectrum

- Spectral Fitting: Numerical fitting of the XANES spectrum to extract d-band parameters while minimizing effects of instrumental and core-hole broadening [14]

This element-specific XANES fitting analysis provides direct experimental validation of computational d-band models and enables the study of structure-property relationships in monometallic and multimetallic nanoparticles under realistic conditions [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Experimental and Computational Resources for D-Band Center Research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Software | VASP [13], Materials Project [10] | DFT calculations, database mining | Plane-wave basis set, PAW pseudopotentials [13] |

| Analysis Tools | pymatgen [10], PyXtal [10] | Materials analysis, symmetry handling | Python-based, open-source [10] |

| Experimental Facilities | Synchrotron XAS [14], XPS [14] | Electronic structure characterization | Element-specific, surface-sensitive [14] |

| Catalyst Materials | Rh-P nanoparticles [1], Pd NPs [14] | Model catalyst systems | Well-defined structure, tunable composition [1] [14] |

| Reference Data | DFT-calculated PDOS [12], adsorption energies [9] | Model training, validation | High-throughput datasets [12] |

Applications in Heterogeneous Catalysis

Catalyst Design and Optimization

D-band center theory has been successfully applied to design high-performance catalysts for various industrially relevant processes. In one notable example, a computation-guided framework was used to design heterogeneous Rh-P nanoparticles that emulate the catalytic properties of homogeneous catalysts for hydroformylation [1]. By employing the d-band center as a transferable electronic descriptor, researchers aligned the electronic structure of Rh-P nanoparticles with that of benchmark Rh-phosphine complexes, enabling predictive control over catalytic activity [1].

The study established a strong quantitative correlation between the deviation in d-band center and catalytic activity (R² = 0.994) [1]. Experimental evaluation revealed that Rh₃P, identified as the optimal composition through electronic structure matching, exhibited superior catalytic activity with a reaction rate of 13,357 h⁻¹, representing a 25% increase over the state-of-the-art RhP nanoparticle system [1].

Water Electrolysis

In renewable energy applications, d-band center theory has proven invaluable in designing electrocatalysts for water splitting. The theory provides a systematic framework for optimizing the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER) by controlling the adsorption strength of reaction intermediates [2].

Common strategies for d-band center modulation in electrocatalysts include [2]:

- Doping: Introducing heteroatoms to modify the local electronic structure

- Strain engineering: Applying tensile or compressive strain to shift d-band center position

- Nanostructuring: Creating low-coordination sites with modified electronic properties

- Alloying: Forming bimetallic or multimetallic systems with optimized d-band characteristics

For example, enhancing the d-band center modulation in carbon-supported CoP via exogenous nitrogen dopants has been shown to significantly boost the ampere-level hydrogen evolution reaction performance [2].

Limitations and Complementary Descriptors

Despite its widespread utility, the d-band center model has recognized limitations, particularly for complex multi-metallic systems [13] [9]. The "abnormal phenomena" of d-band center theory refer to cases where materials with high d-band center positions exhibit weaker than expected adsorption capabilities, or vice versa [13].

These limitations arise because the d-band center carries no information about the band dispersion or asymmetries in the electronic structure introduced by alloying [9]. To address these shortcomings, researchers have developed more comprehensive models such as the Bonding and Anti-bonding Orbitals Stable Electron Intensity Difference (BASED) theory, which achieves higher accuracy (R² = 0.95) for predicting adsorption capability across single-atom catalysts and bulk systems with different adsorption methods [13].

Additionally, the Newns-Anderson model has been extended to account for perturbations in both substrate and adsorbate electronic states upon interaction, revealing a second-order response in chemisorption energy with the d-filling of neighboring atoms [9]. This improved model demonstrates a mean absolute error of 0.13 eV versus DFT reference chemisorption energies for O, N, CH, and Li adsorbates on bi- and tri-metallic surface alloys [9].

The d-band center remains a fundamental electronic descriptor in heterogeneous catalysis research, providing critical insights into the relationship between electronic structure and catalytic function. While the core theory establishes a powerful framework for understanding adsorption trends on transition metal surfaces, contemporary research continues to refine and extend these concepts through integrated computational and experimental approaches.

The ongoing development of machine learning methods, advanced spectroscopic techniques, and more comprehensive electronic structure models ensures that d-band center theory will continue to evolve, addressing its limitations while expanding its applicability to increasingly complex catalytic systems. These advances solidify the position of d-band center analysis as an indispensable tool in the rational design of next-generation catalysts for energy and sustainability applications.

The d-band center theory, originally proposed by Professor Jens K. Nørskov and colleagues, provides a foundational descriptor in the field of surface catalysis that has revolutionized the understanding and design of heterogeneous catalysts [10]. This theory defines the d-band center as the weighted average energy of the d-orbital projected density of states (PDOS) for transition metals and their alloys, typically referenced relative to the Fermi level [10]. This quantity plays a crucial role in determining the adsorption strength of reactants or intermediates on transition metal surfaces, thereby serving as an essential electronic descriptor for adsorption behavior in heterogeneous catalysis [10].

The fundamental principle underlying this model states that a higher d-band center (closer to the Fermi level) correlates with stronger bonding interactions between the d orbitals of the transition metal and the s or p orbitals of adsorbates [10]. Conversely, a lower d-band center (further below the Fermi level) results in weaker interactions due to the increased population of anti-bonding states, thereby reducing adsorption energies [10]. This behavior is fundamentally rooted in the principles of orbital hybridization and electronic filling, creating a powerful predictive framework for catalyst design.

Fundamental Principles of the Hammer-Nørskov d-Band Model

Theoretical Foundation

The Hammer-Nørskov d-band model represents a simplified yet powerful approach to understanding chemisorption on transition metal surfaces, conceptually derived as a narrow d-band limit of the Newns-Anderson model [15]. In this framework, the continuous band of d-states participating in the surface-adsorbate interaction is approximated by a single state at energy εd, known as the center of the d-band [15]. According to this model, variations in adsorption energy from one transition metal surface to another correlate with the upward shift of this d-band center relative to the Fermi energy [15].

The underlying electronic mechanism can be summarized as follows: an upward shift in the d-band center indicates the potential formation of a larger number of empty anti-bonding states, leading to stronger binding energy [15]. This upward shift of the d-band center therefore serves as a reliable descriptor of catalytic activity across different transition metal surfaces and has been successfully applied to explain both experimental and first-principles theoretical results for various ligands and molecules on diverse transition metal surfaces [15].

Mathematical Formulation

The d-band center is typically calculated using an energy-weighted integration of the projected density of states (PDOS) of the d orbitals within a selected energy window [10]. Mathematically, this is represented as a moment of the density of states distribution, where the first moment (center of mass) of the d-band provides the d-band center position. The PDOS required for this calculation is derived from density functional theory (DFT) calculations, which involve solving the Kohn-Sham equations using numerical methods such as diagonalization techniques to obtain the wavefunctions of the system, which are then projected onto the d orbital [10].

Table 1: Key Relationships in d-Band Center Theory

| d-Band Center Position | Interaction with Adsorbate | Adsorption Strength | Underlying Electronic Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Higher (closer to Fermi level) | Stronger bonding interactions | Increased adsorption energy | More empty anti-bonding states |

| Lower (further from Fermi level) | Weaker interactions | Reduced adsorption energy | Increased population of anti-bonding states |

Limitations and Extensions of the Conventional Model

The Spin-Polarization Challenge

While the conventional d-band model has demonstrated remarkable success across various catalytic systems, it exhibits significant limitations when applied to magnetically polarized transition metal surfaces [15]. Research has revealed that the model is inadequate for capturing the complete catalytic activity of surfaces with high spin polarization, necessitating its generalization [15]. This limitation becomes particularly evident for 3d transition metals (V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, and Zn) where spin effects substantially influence adsorption behavior [15].

For magnetic surfaces, adsorption energies can differ significantly between spin-polarized and non-spin-polarized calculations [15]. This occurs because when spin polarization is considered, the system effectively exhibits two d-band centers: one for spin-up states (εd↑) and another for spin-down states (εd↓) [15]. These centers shift in opposite directions relative to the unpolarized d-band center, with εd↑ moving downward and εd↑ moving upward with respect to εd [15]. The interaction of these spin-separated centers with adsorbate orbitals leads to a competition between spin-dependent metal-adsorbate interactions, resulting in non-linear dependencies of adsorption energy that the conventional single d-band center cannot capture [15].

Extended Two-Centered d-Band Model

To address these limitations, a generalized two-centered d-band model has been developed [15]. In this extended framework, the adsorption energy accounts for spin-dependent interactions through the expression:

[ \Delta E{ads} = \sum{\sigma} \left[ \sum{i} \frac{|V{ak,d\sigma}|^2 (1 - f{\sigma})}{\varepsilon{ak} - \varepsilon{d\sigma}} - \sum{j} \frac{|V{aj,d\sigma}|^2 f{\sigma}}{\varepsilon{aj} - \varepsilon{d\sigma}} \right] + \alpha \left( \sum{i} |V{ak,d\sigma}|^2 + \sum{j} |V{aj,d\sigma}|^2 \right) ]

Where σ represents spin channels (↑, ↓), fσ is the fractional filling of the metal state with spin σ, εak and εaj are energies of unoccupied and occupied adsorbate states respectively, V represents coupling matrix elements, and α is an adjustable parameter with units of eV⁻¹ [15].

This generalized model reveals that for surfaces with high spin polarization, the minority spin d-bands bind more strongly to adsorbates, while binding with majority spin states is weaker [15]. This phenomenon results from the asymmetric distribution of anti-bonding states across spin channels and explains significant changes in adsorption energies for magnetic elements like Mn and Fe that the conventional model cannot accurately predict [15].

Computational Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Density Functional Theory Calculations

The reliable determination of d-band centers and adsorption energies relies on well-established density functional theory protocols. The following methodology represents standard practice in the field:

Data Set Construction and Computational Parameters:

- Structures containing transition metal elements and their corresponding projected density of states (PDOS) data are typically sourced from materials databases such as the Materials Project [10]

- DFT calculations are generally performed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) [10]

- Exchange-correlation functionals: GGA (Generalized Gradient Approximation) or GGA+U for systems with strong electron correlations [10]

- Core-electron interactions: Projector-Augmented Wave (PAW) method [10]

- Plane-wave kinetic energy cutoff: 520 eV [10]

- k-point mesh: Automatic generation with density of 60/ų [10]

- Electronic self-consistent loop energy convergence: 10⁻⁶ eV [10]

- Ionic relaxation convergence: 0.01 eV/Å force on each atom [10]

d-Band Center Calculation Workflow:

- Perform full geometry optimization of the crystal structure

- Calculate the electronic density of states with higher precision

- Project the density of states onto d-orbitals of transition metal atoms

- Compute the d-band center using the energy-weighted integration of d-projected DOS:

[ \varepsilond = \frac{\int{-\infty}^{\infty} E \cdot \text{PDOS}d(E) dE}{\int{-\infty}^{\infty} \text{PDOS}_d(E) dE} ]

where the energy reference is set to the Fermi level [10]

Machine Learning Approaches

Recent advancements have introduced machine learning methodologies to address computational bottlenecks in high-throughput screening:

DOSnet Architecture:

- Utilizes convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to automatically extract relevant features from density of states data [16]

- Input: Site and orbital projected DOS of relevant surface atoms participating in chemisorption [16]

- For top-site adsorption: DOS of one surface atom split into nine channels (s, py, pz, px, dxy, dyz, dz², dxz, dx²-y²) [16]

- For bridge-site adsorption: DOS of two bridging surface atoms (18 channels) [16]

- For hollow-site adsorption: DOS of three nearest neighbor surface atoms (27 channels) [16]

- Achieves mean absolute error of approximately 0.1 eV for adsorption energy prediction across diverse adsorbates and surfaces [16]

DOTA (DOS Transformer for Adsorption) Framework:

- Implements transformer architecture with multi-head self-attention mechanisms [17]

- Leverages local density of states (LDOS) as input to predict adsorption energies [17]

- Pretrained on PBE-level DFT data, then fine-tuned with minimal high-fidelity experimental or hybrid functional data [17]

- Allocates 32 angular momentum-projected DOS embedding channels per surface atom and 8 PDOS embedding channels per adsorbate atom [17]

- Capable of resolving longstanding challenges such as the "CO puzzle" [17]

Table 2: Computational Methods for d-Band Center and Adsorption Energy Calculation

| Method | Key Features | Accuracy | Computational Cost | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard DFT (GGA/PBE) | Well-established, widely adopted | Functional-dependent errors (e.g., CO puzzle) | High for large-scale screening | Systematic errors in adsorption energies |

| DFT with Hybrid Functionals (HSE06) | Improved electronic structure description | Higher accuracy for molecular adsorption | ~10-100× GGA | Prohibitively expensive for high-throughput screening |

| Machine Learning (DOSnet) | Automatic feature extraction from DOS | MAE ~0.1 eV for adsorption energies | Low after training | Requires large training datasets |

| Deep Learning (DOTA) | Transfer learning across quantum methods | Chemically accurate after fine-tuning | Low after training | Complex architecture, requires expertise |

Computational Workflow for d-Band Center Analysis

Advanced Applications and Research Frontiers

Inverse Materials Design with Generative Models

The integration of d-band center theory with advanced deep generative models represents a cutting-edge frontier in computational catalysis research. The dBandDiff framework exemplifies this approach, implementing a conditional generative diffusion model for crystal structure design guided jointly by target d-band center values and space group symmetry [10]. This model builds upon the DiffCSP++ unconditional generation framework, adopting the Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (DDPM) paradigm [10].

Key features of this advanced approach include:

- Incorporation of a periodic feature-enhanced Graph Neural Network as a denoiser [10]

- Enforcement of Wyckoff position constraints during both forward and denoising stages [10]

- Generation of novel structures that adhere to target space group symmetry with 98.7% compliance [10]

- High-throughput DFT validation confirming 72.8% of generated structures as geometrically and energetically reasonable [10]

- Significantly smaller deviations of calculated d-band centers from target values compared to random sampling [10]

In practical demonstration, dBandDiff successfully identified novel materials with target d-band centers of 0 eV (associated with strong adsorption capability), with 17 reasonable materials exhibiting computed d-band centers within ±0.25 eV of the target value [10]. This approach offers substantial advantages in both efficiency and computational cost compared to conventional element substitution workflows [10].

Electrocatalytic Water Splitting Applications

The d-band center theory has found particularly valuable applications in the design of non-noble metal-based electrocatalysts for enhanced electrocatalytic water splitting [18]. Tuning the d-band center of iron-series (Fe, Co, Ni) metal-based materials has emerged as a strategic approach for developing efficient electrocatalysts [18].

Table 3: d-Band Center Optimization in Iron-Series Electrocatalysts

| Material Class | Representative Catalysts | d-Band Center Optimization Strategy | Catalytic Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickel Oxide | NiO nanorods with O-vacancies | Introduction of oxygen vacancies | ~110 mV overpotential @ 10 mA cm⁻² for HER [18] |

| Cobalt Oxide | Defect-rich Co₃O₄ nanosheets | Oxygen defects engineering | Reduced band gap, improved OER kinetics [18] |

| Iron Oxide | Ni-doped Fe₃O₄ on iron foil | Cation doping to modify electronic structure | Enhanced OER through coexistence of Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ [18] |

| Hydroxides | Co(OH)₂, Ni(OH)₂, Fe(OH)₃ | In situ transformation to active phases | Transformation to Co₃O₄/CoOOH (OER), Ni(OH)₂ stability (HER) [18] |

| Oxyhydroxides | FeOOH, CoOOH, NiOOH | Binary metal combinations (Fe-Co, Fe-Ni, Ni-Co) | Enhanced OER: FeOOH > CoOOH > NiOOH [18] |

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for d-Band Center Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in d-Band Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| VASP | Software | Ab initio DFT calculations | Electronic structure calculation, PDOS determination [10] |

| Materials Project | Database | Crystallographic and DFT data | Source of structural models and reference calculations [10] |

| PyXtal | Library | Crystal structure generation and symmetry analysis | Structure manipulation and symmetry constraint implementation [10] |

| pymatgen | Library | Materials analysis | Structure and DOS analysis utilities [10] |

| DOSnet | ML Model | Adsorption energy prediction | Feature extraction from DOS for adsorption energy prediction [16] |

| DOTA | ML Framework | Transformer-based adsorption prediction | Chemically accurate adsorption energies using LDOS inputs [17] |

| dBandDiff | Generative Model | Inverse materials design | Generating structures with target d-band centers [10] |

Research Applications and Future Directions of d-Band Center Theory

The Hammer-Nørskov d-band model has evolved from its original formulation as a correlation between d-band center position and adsorption strength into a comprehensive theoretical framework that continues to guide catalyst design. While the fundamental relationship—that higher d-band centers correlate with stronger adsorption—remains valid, contemporary research has significantly expanded this paradigm to account for spin effects [15], machine learning enhancements [17] [16], and generative inverse design [10]. The theory has proven particularly valuable in developing earth-abundant alternatives to noble metal catalysts, especially in electrocatalytic water splitting applications where iron-series metal-based compounds show particular promise [18].

Future directions in d-band center research will likely focus on addressing the remaining limitations of current models, including dynamic changes under operational conditions, more sophisticated treatments of spin effects in complex magnetic systems, and integration with multi-descriptor approaches that capture complementary aspects of surface reactivity. The ongoing integration of machine learning and generative models promises to further accelerate the discovery and optimization of novel catalytic materials with tailored electronic structures for specific applications, solidifying the d-band center's role as a cornerstone descriptor in heterogeneous catalysis research.

Why d-Orbitals? The Role of Transition Metals in Catalytic Bonding

The unique catalytic properties of transition metals are fundamentally rooted in the electronic structure of their d-orbitals. This whitepaper examines the central role of d-orbitals in catalytic bonding, with a specific focus on the d-band center theory as a unifying principle in heterogeneous catalysis research. The ability of transition metals to facilitate complex chemical transformations stems from their partially filled d-orbitals, which enable precise adsorption of reactant molecules and formation of reaction intermediates. By exploring the fundamental electronic properties, theoretical frameworks, and experimental evidence connecting d-orbital characteristics to catalytic activity, this review provides researchers with a comprehensive understanding of how d-orbital engineering enables the rational design of advanced catalysts for energy and chemical applications.

Transition metals are defined as elements whose atoms have a partially filled d sub-shell or that can form cations with incomplete d orbitals [19] [20]. This electronic configuration provides them with unique catalytic properties that distinguish them from other elements in the periodic table.

Fundamental Electronic Characteristics

The electronic structure of transition metals follows the general configuration [noble gas] (n−1)d¹⁻¹⁰ns⁰⁻², where the d orbitals are the next-to-last subshell and are denoted as (n−1)d [20]. A critical aspect of transition metal chemistry is that when d-block elements form ions, the 4s electrons are always lost first before the 3d electrons [19]. For example, cobalt (Co, [Ar] 3d⁷4s²) forms Co²⁺ ([Ar] 3d⁷) through the loss of the two 4s electrons, preserving the d-electron count that is essential for catalytic functionality.

The defining characteristic of transition metals is their partially filled d orbitals, which enable variable oxidation states, complex ion formation, colored ions, and catalytic activity [19]. Elements such as zinc (which has a full d¹⁰ configuration) are generally not considered transition metals under the strict definition because they do not form ions with incomplete d orbitals [19] [20].

Table 1: Electronic Configuration of First-Row Transition Metals

| Element | Atomic Number | Electronic Configuration | Incomplete d-shell? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sc | 21 | [Ar] 3d¹4s² | Yes |

| Ti | 22 | [Ar] 3d²4s² | Yes |

| V | 23 | [Ar] 3d³4s² | Yes |

| Cr | 24 | [Ar] 3d⁵4s¹ | Yes |

| Mn | 25 | [Ar] 3d⁵4s² | Yes |

| Fe | 26 | [Ar] 3d⁶4s² | Yes |

| Co | 27 | [Ar] 3d⁷4s² | Yes |

| Ni | 28 | [Ar] 3d⁸4s² | Yes |

| Cu | 29 | [Ar] 3d¹⁰4s¹ | Yes (Cu²⁺: [Ar] 3d⁹) |

| Zn | 30 | [Ar] 3d¹⁰4s² | No (Zn²⁺: [Ar] 3d¹⁰) |

d-Band Center Theory: Fundamentals and Principles

The d-band center theory, originally proposed by Professor Jens K. Nørskov, provides a foundational framework for understanding and predicting catalytic activity in transition metal systems [10]. This theory defines the d-band center as the weighted average energy of the d-orbital projected density of states (PDOS) for transition metal systems, typically referenced relative to the Fermi level [10].

Theoretical Foundation

The d-band center (ε_d) is mathematically calculated using the formula that involves performing an energy-weighted integration of the PDOS of the d orbitals within a selected energy window [10]. This electronic descriptor plays a crucial role in determining the adsorption strength of reactants or intermediates on transition metal surfaces, serving as an essential parameter for understanding adsorption behavior in heterogeneous catalysis [10].

The fundamental relationship established by d-band center theory states that:

- A higher d-band center (closer to the Fermi level) correlates with stronger bonding interactions between the d orbitals of the transition metal and the s or p orbitals of adsorbates

- A lower d-band center (further below the Fermi level) results in weaker interactions due to increased population of anti-bonding states, thereby reducing adsorption energies [10]

This behavior is fundamentally rooted in the principles of orbital hybridization and electronic filling, providing a powerful predictive tool for catalytic design.

Extension to Homogeneous-Heterogeneous Catalysis Unification

Recent advances have demonstrated that the d-band center serves as a transferable electronic descriptor that can unify molecular-level reactivity across homogeneous and heterogeneous catalytic systems [1]. In a groundbreaking study, researchers established a strong quantitative correlation between the deviation in d-band center and catalytic activity (R² = 0.994) for Rh-P nanoparticles designed to emulate homogeneous Rh-phosphine complexes [1].

This unification enables predictive control over catalytic activity, as demonstrated by the identification of Rh₃P as the optimal composition through electronic structure matching with benchmark homogeneous catalysts. Experimental validation confirmed that Rh₃P achieved a reaction rate of 13,357 h⁻¹, representing a 25% increase over the state-of-the-art RhP nanoparticle system [1].

d-Orbital Engineering Strategies in Catalytic Design

The strategic manipulation of d-orbital electronic properties has emerged as a powerful approach for designing advanced catalysts with enhanced activity and selectivity.

Coordination Engineering

Coordination engineering enables precise control over the geometric and electronic structure of metal active sites by manipulating their coordination environment. Research on Cu single-atom catalysts (SACs) has demonstrated that reducing coordination number from Cu-N₄ to Cu-N₃ significantly enhances catalytic performance for benzene oxidation [21].

The tri-coordinated Cu SAC (Cu-N₃-33.2) exhibited exceptional performance with 85.8% benzene conversion and a turnover frequency of 680.3 h⁻¹ at 60°C [21]. Experimental and computational analyses revealed that this enhanced activity stems from dynamically formed Cu-O intermediates, driven by p-d orbital hybridization between Cu (d orbitals) and O (p orbitals), which lowered the H₂O₂ activation barrier by 0.98 eV compared to Cu-N₄ sites [21].

Orbital Hybridization Strategies

Orbital hybridization represents another powerful strategy for tuning the electronic properties of transition metal catalysts. Unlike conventional d-d hybridization, d-sp hybridization between transition metals and p-block elements can result in surprising electronic properties and catalytic activities [22].

This approach has been successfully implemented in various catalyst architectures including:

- p-block element-doped metal catalysts

- Intermetallic catalysts

- Supported metal catalysts

The d-sp hybridization strategy has shown particular promise for energy-related electrocatalytic applications, offering enhanced control over surface chemisorption properties [22].

Bimetallic Systems and Electronic Modulation

Incorporating bimetallic systems provides additional dimensions for d-orbital engineering through strong electronic interactions between different metal centers. Studies on Fe-N₄/Gr and bimetallic FeN₄-MN₄/Gr systems have revealed that encapsulation of bimetallic atoms has a prominent effect on catalytic activity due to strong electronic interactions between bimetallic atoms, which alter spin states, electron transfer paths, and energy barriers [23].

In diatomic systems, whether composed of similar or different metal atoms, collaborative effects change adsorption energy, chemical bonds, reaction energy barriers, and reaction paths of intermediates [23]. These modifications enable fine-tuning of catalytic properties beyond what is achievable with single-metal systems.

Table 2: d-Orbital Engineering Strategies and Their Effects on Catalytic Properties

| Engineering Strategy | Key Mechanism | Catalytic Impact | Example System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coordination Engineering | Modification of local crystal field and d-orbital splitting | Lowered activation barriers, enhanced selectivity | Cu-N₃ for benzene oxidation [21] |

| d-sp Orbital Hybridization | Electronic interaction between metal d and p-block element sp orbitals | Optimized adsorption strength, improved activity | p-block element-doped metals [22] |

| Bimetallic Incorporation | Electronic modulation through metal-metal interactions | Modified reaction pathways, synergistic effects | FeN₄-MN₄/Gr systems [23] |

| Compositional Tuning | d-band center alignment with reference catalysts | Unified homogeneous-heterogeneous activity | Rh₃P nanoparticles [1] |

Experimental Methodologies and Characterization

Computational Workflows for d-Band Center Analysis

The determination of d-band center properties relies on sophisticated computational workflows integrating multiple theoretical approaches:

Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations

- Methodology: Periodic DFT calculations performed using software packages such as Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) [23] [10]

- Key Parameters: Projector augmented wave (PAW) method, generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation functional, kinetic energy cut-off of 500 eV [23]

- k-point Sampling: Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid for Brillouin zone integration [23]

- PDOS Analysis: Projected density of states (PDOS) calculations for d-orbital contribution analysis [23]

Machine Learning-Accelerated Approaches Recent advances have integrated machine learning with computational materials science to develop regression models that predict electronic properties from structural features [10]. More sophisticated deep generative models, such as diffusion-based frameworks conditioned on target d-band center values, have emerged for inverse materials design [10]. The dBandDiff model exemplifies this approach, generating crystal structures with target d-band centers ranging from -3 eV to 0 eV across 50 common space groups, with 72.8% of generated structures being geometrically and energetically reasonable [10].

Experimental Synthesis Protocols

Preparation of Single-Atom Catalysts with Defined Coordination

- Method: Self-assembly strategy decoupling coordination engineering from metal loading optimization [21]

- Procedure:

- Self-assembly of guanine molecules through supramolecular interactions and π-π stacking

- Binding of metal ions (e.g., Cu²⁺) to N sites in guanine structure

- Controlled pyrolysis under N₂ environment at high temperature (typically 800-900°C)

- Key Control Parameters: Cu²⁺ ion concentration, pyrolysis temperature and atmosphere

- Outcome: Cu SACs with controlled coordination number (Cu-N₃ vs. Cu-N₄) and metal loading up to 33.2 wt% [21]

Workflow for Heterogeneous Catalyst Design Integrating d-Band Center Principles

Advanced Characterization Techniques

A comprehensive suite of characterization methods is essential for correlating d-orbital properties with catalytic performance:

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS)

- Application: Determination of local electronic and geometric structures of metal centers [21]

- Key Measurements: Cu K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) for oxidation state analysis; extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) for coordination environment [21]

Electron Microscopy

- Aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM: Direct visualization of atomic dispersion of metal atoms [21]

- EDX Elemental Mapping: Confirmation of uniform element distribution [21]

Surface Analysis

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Analysis of surface chemical compositions and electronic states [21]

- In-situ ATR-IR Spectroscopy: Monitoring of reaction intermediates and mechanistic pathways [21]

Electronic Structure Analysis

- Partial Density of States (PDOS): Calculation of d-orbital contributions to electronic structure [23]

- Bader Charge Analysis: Investigation of charge transfer effects in bimetallic systems [23]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Experimental Reagents and Computational Tools for d-Orbital Catalysis Research

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) | DFT calculations for electronic structure analysis | [23] [10] |

| dBandDiff (Generative Model) | Inverse design of materials with target d-band center | [10] | |

| Characterization Techniques | X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS) | Probing local electronic structure and coordination | [21] |

| Aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM | Verifying atomic dispersion in single-atom catalysts | [21] | |

| In-situ ATR-IR Spectroscopy | Monitoring reaction intermediates and pathways | [21] | |

| Synthesis Precursors | Guanine molecules | Self-assembly precursor for SACs with defined coordination | [21] |

| Metal salts (e.g., Cu²⁺, Rh³⁺) | Metal precursors for active site formation | [1] [21] | |

| Support Materials | Defective graphene | Substrate for anchoring single metal atoms | [23] |

| N-doped carbon | Support material with tunable electronic properties | [21] |

The pivotal role of d-orbitals in transition metal catalysis is unequivocally established through both theoretical frameworks and experimental validation. The d-band center theory provides a powerful predictive descriptor that enables rational catalyst design across homogeneous and heterogeneous systems. By strategically manipulating d-orbital characteristics through coordination engineering, orbital hybridization, and bimetallic interactions, researchers can precisely control catalytic activity, selectivity, and stability.

Future advancements in this field will likely focus on the integration of machine learning and generative models for accelerated catalyst discovery, combined with sophisticated operando characterization techniques to provide dynamic insights into d-orbital participation during catalytic reactions. The continued unification of fundamental electronic principles across different catalytic paradigms promises to enable the design of next-generation catalysts for sustainable chemical and energy applications.

The rational design of high-performance catalysts is a central pursuit in chemical research, critical for developing sustainable energy solutions and efficient chemical processes. At the heart of this endeavor lies the Sabatier principle, a foundational concept in heterogeneous catalysis that states the optimal catalyst must bind reaction intermediates with neither too strong nor too weak intensity [24]. When graphically represented, this principle yields the characteristic volcano plot that correlates a descriptor of binding strength with catalytic activity, positioning the most active catalysts at the peak [25]. For decades, this principle provided qualitative guidance but lacked the quantitative precision needed for predictive catalyst design.

The advent of d-band center theory has transformed this landscape by providing the crucial electronic structure descriptor that quantifies the Sabatier principle. Introduced by Hammer and Nørskov, this theory establishes that the average energy of the d-electron states (the d-band center, εd) relative to the Fermi level fundamentally governs an adsorbate's binding strength on transition metal surfaces [2] [26] [27]. When the d-band center is closer to the Fermi level, stronger adsorption occurs due to elevated anti-bonding state energies; when farther away, adsorption weakens [26]. This powerful descriptor enables researchers to computationally predict catalytic activities and rationally design new catalysts before synthetic validation [27].

This technical guide explores the fundamental relationship between the d-band center and the Sabatier principle, demonstrating how this electronic descriptor predicts the characteristic volcano-shaped activity relationships across diverse catalytic systems. We examine the theoretical foundations, computational methodologies, and experimental applications of these concepts, with particular emphasis on their implementation in designing advanced catalytic materials for energy-related reactions.

Theoretical Foundations and Relationship

The Quantitative Sabatier Principle and Volcano Plots

The classical Sabatier principle states that the most desirable catalytic activity is located at the peak of the volcano plot, where adsorption is "just right" [25]. The transition from a qualitative principle to a quantitative predictive theory emerged through computational electronic structure methods that systematically treated adsorption energies and activation barriers on metal surfaces [24]. This quantification revealed that a single descriptor—often an adsorption energy—could represent the "bond strength" between catalysts and key intermediates.

The volcano relationship emerges because catalysts with weak binding fail to activate reactants (left side of volcano), while those with strong binding suffer from product desorption limitations (right side of volcano) [24]. The peak represents the optimal compromise between these competing factors. For the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), the hydrogen adsorption free energy (ΔGH) has been established as an excellent descriptor, with ΔGH = 0 eV representing the ideal "just right" bonding scenario [25].

Table 1: Key Energy Descriptors for Selected Catalytic Reactions

| Reaction | Key Intermediate | Descriptor | Optimum Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Evolution (HER) | H* | ΔGH* | 0 eV | [25] |

| Oxygen Reduction (ORR) | O, OH | ΔGO* - ΔGOH* | - | [26] |

| Ammonia Synthesis | N* | ΔGN* | - | [24] |

| CO2 Reduction | COOH* | ΔGCOOH* | - | [26] |

D-Band Center Theory as the Electronic Foundation

The d-band center theory provides the electronic structure basis that explains why different transition metals exhibit distinct adsorption strengths. For transition metals, the total electronic band structure comprises sp-bands and d-bands. The theory posits that the d-band center position relative to the Fermi level primarily determines surface-adsorbate bond strength [2] [26]. Mathematically, the d-band center (εd) is calculated as the first moment of the d-band density of states:

εd = ∫Eρd(E)dE/∫ρd(E)dE

where E is energy relative to the Fermi level and ρd(E) is the density of d-states [26].

When the d-band center is higher (closer to the Fermi level), the anti-bonding states shift upward in energy and become less filled, resulting in stronger adsorption [26]. Conversely, a lower d-band center (further from Fermi level) leads to more filled anti-bonding states and consequently weaker adsorption. This fundamental relationship enables researchers to understand and predict adsorption trends across different transition metal surfaces and their alloys.

Table 2: D-Band Center Values and Corresponding Adsorption Properties

| Catalyst Material | D-Band Center (εd, eV) | Adsorption Strength | Catalytic Implications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt (111) | -1.66 eV (unstained) | Strong H* binding | Baseline HER performance | [25] |

| Pt with 6.8% compressive strain | -2.03 eV | Weaker H* binding | Improved HER kinetics | [25] |

| High entropy alloys | Distribution around μ | Varying adsorption sites | Enhanced spillover effects | [25] |

| FeCoNiMnMoP | Lower than FeCoNiMnP | Optimized intermediate binding | Superior bifunctional activity | [28] |

Connecting d-Band Center to Volcano Plots

The fundamental connection between the d-band center and volcano plots emerges because εd serves as an excellent predictor of adsorption energies, which in turn function as the activity descriptors in volcano relationships. This creates a causal chain: d-band center position → adsorption energy → catalytic activity → volcano plot position.

This relationship enables computational screening of catalysts by calculating their d-band centers and predicting their approximate volcano plot positions without exhaustive experimental testing. For instance, compressive strain in PtFeCoNiCu high-entropy alloys shifts the d-band center downward (from -1.66 eV to -2.03 eV), weakening hydrogen adsorption and moving the catalyst closer to the volcano peak for HER [25]. Similarly, in FeCoNiMnMoP high-entropy electrocatalysts, the introduction of Mo reduces the d-band center and enhances the density of states at the Fermi level, optimizing both HER and OER activities [28].

Computational Methodologies and Experimental Validation

Density Functional Theory (DFT) Protocols

The computational determination of d-band centers and adsorption energies relies predominantly on density functional theory calculations with well-established protocols:

Surface Modeling: Catalytic surfaces are typically modeled as periodic slabs with sufficient vacuum spacing (typically ≥15 Å) to prevent interactions between periodic images. For high-entropy alloys, special quasi-random structures (SQS) or large supercells are employed to capture the inherent disorder and elemental heterogeneity [25].

Electronic Structure Calculation: DFT calculations are performed using plane-wave basis sets with pseudopotentials to describe core electrons. The Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional is commonly employed for exchange-correlation effects. A k-point mesh following Monkhorst-Pack scheme ensures adequate Brillouin zone sampling [25] [26].

D-Band Center Determination: After geometric optimization, the density of states (DOS) is calculated with higher k-point density. The d-band center (εd) is computed as the first moment of the d-band projected density of states (PDOS) using the equation: εd = ∫Eρd(E)dE/∫ρd(E)dE, where the integration spans the d-band energy range [26].

Adsorption Energy Calculations: Adsorption energies (ΔEads) for key intermediates (H, O, OH*, etc.) are calculated as: ΔEads = E(surface+adsorbate) - E(surface) - E(adsorbate), where E(surface+adsorbate) is the total energy of the optimized slab with adsorbate, E(surface) is the energy of the clean slab, and E(adsorbate) is the reference energy of the isolated adsorbate molecule [25]. For electrochemical reactions, adsorption free energies are obtained by incorporating zero-point energy, enthalpy, entropy, and solvation corrections: ΔG = ΔE + ΔZPE - TΔS + ΔGU + ΔGsolv [26].

Advanced Descriptor Implementation

Beyond conventional d-band center analysis, several advanced implementations have enhanced predictive capabilities:

Generalized d-Band Center: For complex nanostructures like low-symmetry Pt nanoparticles, a generalized d-band center normalized by coordination number has been employed to predict CO adsorption energies with mean absolute errors of ~0.23 eV [27].

Multi-Descriptor Approaches: In complex reactions like oxygen evolution, multiple descriptors (δ and ε) have been introduced, where δ is limited by adsorption energy scaling relationships while ε remains unaffected by such limitations, enabling more comprehensive activity predictions [26].

Machine Learning Integration: The d-band center serves as a key feature in machine learning models for catalyst screening. For instance, feed-forward artificial neural networks incorporating d-band centers of bonding metal atoms have successfully predicted adsorption energies of CO and OH on bimetallic surfaces, enabling efficient screening of methanol electro-oxidation catalysts [27].

Experimental Synthesis and Validation Protocols

High-Entropy Alloy Synthesis (PtFeCoNiCu): The PtFeCoNiCu HEA catalyst is synthesized with a dual gradient design. A Pt concentration gradient is established across layers (100.0%, 50.0%, 25.0%, 12.5%, and 12.5% from surface to bulk) to create compositional heterogeneity. Smaller atomic radii elements (Fe, Co, Ni, Cu) induce compressive strain on surface Pt atoms, modulating electronic structure. Materials are characterized using XRD, TEM, and XPS to verify structure, morphology, and surface composition [25].

High-Entropy Intermetallic Compound Synthesis (FeCoNiMnMoP): The FeCoNiMnMoP HEIC is prepared via electrodeposition on nickel foam substrate. Metal precursors (FeCl₃·6H₂O, CoCl₂·6H₂O, NiCl₂·6H₂O, MnCl₂·4H₂O, Na₂MoO₄·2H₂O) and phosphorus source (NaH₂PO₂·H₂O) are dissolved in deionized water. Electrodeposition is performed at controlled potential and temperature with continuous stirring. The resulting material is rinsed with ethanol and water, then dried under vacuum [28].

Electrochemical Performance Evaluation: HER activity is measured in acidic (0.5 M H₂SO₄) or alkaline (1 M KOH) electrolyte using standard three-electrode configuration. Catalysts are deposited on glassy carbon electrodes with Nafion binder. Linear sweep voltammetry is performed from 0.1 to -0.3 V vs. RHE at 2-5 mV/s scan rate. Overpotential at -10 mA cm⁻² and Tafel slope are extracted from polarization curves. Accelerated stability tests are conducted via continuous cycling [25] [28].

Material Characterization: Synchrotron-based X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) validate electronic structure modifications. Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) maps elemental distribution in high-entropy materials [25] [28].

Case Studies and Research Applications

Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER) on High-Entropy Alloys

The hydrogen evolution reaction represents an ideal system for studying the Sabatier principle due to its relatively simple mechanism and the well-established hydrogen adsorption energy (ΔGH) as an activity descriptor. Recent research on PtFeCoNiCu high-entropy alloys has revealed an unusual Sabatier principle where the ΔGH values follow a Gaussian distribution across diverse surface sites rather than exhibiting a single value [25].

DFT calculations on PtFeCoNiCu HEA surfaces with varying compressive strains demonstrated that ΔGH* follows a Gaussian distribution [X ~ N(μ, σ²)], where μ represents the mean adsorption energy and σ represents the standard deviation. The study discovered that catalytic activity improves when μ approaches 0 eV and σ increases, creating sites with ΔGH* < μ - σ that strongly adsorb H* (favorable for Volmer step) and sites with ΔGH* > μ + σ that weakly adsorb H* (favorable for Tafel/Heyrovsky steps) [25]. This spatial variation enables hydrogen spillover with small diffusion barriers (0.232 eV), effectively circumventing the traditional Sabatier principle limitation.

Experimental validation confirmed this theoretical insight, with synthesized PtFeCoNiCu HEA catalysts demonstrating exceptional HER performance with an overpotential of only 10.8 mV at -10 mA cm⁻² and 4.6 times higher intrinsic activity compared to state-of-the-art Pt/C [25]. This case study illustrates how the combination of d-band center analysis and adsorption energy distributions enables breakthrough catalytic performance.

Bifunctional Water Splitting Catalysts

The FeCoNiMnMoP high-entropy intermetallic compound represents another successful application of descriptor-guided design for bifunctional water splitting. Guided by the Sabatier principle and volcano curves, this catalyst was designed by combining elements on both sides of the HER volcano (Fe, Co, Ni on the left; Mo on the right) to create optimal M-H bonding energy [28].

DFT calculations revealed that FeCoNiMnMoP exhibits a lower d-band center and higher density of states at the Fermi level compared to FeCoNiMnP. The synergistic interaction between multiple sites reduced energy barriers for both HER and OER. Theoretical models identified Ni-Mn-Mo and Co-Mn-Mo as the optimal configurations for HER and OER, respectively [28].

Experimentally, the FeCoNiMnMoP catalyst delivered outstanding bifunctional performance in alkaline media, with overpotentials of only 55 mV for HER and 221 mV for OER at 10 mA cm⁻². In overall water splitting configuration, the FeCoNiMnMoP||FeCoNiMnMoP couple required only 1.49 V to achieve 10 mA cm⁻², superior to most reported high-entropy catalysts [28]. This demonstrates the power of descriptor-based design for complex multi-functional catalytic systems.

Extension Beyond Electrocatalysis

The applicability of the Sabatier principle and descriptor-based analysis extends beyond traditional heterogeneous catalysis into emerging fields. Recent research has demonstrated that self-sufficient heterogeneous biocatalysts (ssHBs) for redox biotransformations obey the Sabatier principle, with maximum catalytic efficiency achieved at intermediate cofactor-polymer binding strength [29].

In these systems, adjustment of pH and ionic strength modulates the electrostatic interactions between enzymes/cofactors and cationic polymer supports, resulting in the characteristic volcano-shaped activity relationship [29]. This confirms the universal nature of the Sabatier principle across diverse catalytic systems and provides design strategies for optimizing binding thermodynamics in biocatalytic applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for d-Band Center and Volcano Plot Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Precursors (FeCl₃·6H₂O, CoCl₂·6H₂O, NiCl₂·6H₂O, etc.) | Synthesis of alloy catalysts via various methods | Preparation of high-entropy alloys and intermetallic compounds | [28] |

| NaH₂PO₂·H₂O | Phosphorus source for phosphide catalysts | Synthesis of FeCoNiMnMoP high-entropy intermetallic compound | [28] |

| Nafion Binder | Ionomer for electrode preparation | Fabrication of working electrodes for electrochemical testing | [25] |

| Acidic/Alkaline Electrolytes (H₂SO₄, KOH) | Reaction medium for electrocatalytic testing | Evaluation of HER/OER performance in different pH conditions | [25] [28] |

| Cationic Polymers (e.g., Polyethylenimine) | Support functionalization for biocatalysts | Creating electrostatic interactions for cofactor immobilization | [29] |

| Nickel Foam/ Carbon Paper | Conductive substrate for catalyst loading | Providing high surface area support for electrocatalyst deposition | [28] |

The integration of the Sabatier principle with d-band center theory has fundamentally transformed catalyst design from empirical exploration to rational prediction. The quantitative relationship between electronic structure descriptors and catalytic activity enables targeted materials development with reduced trial-and-error cycles. Several emerging trends are shaping the future of this field:

Machine Learning Acceleration: The d-band center is increasingly serving as a key feature in machine learning models for high-throughput catalyst screening. These approaches can predict adsorption energies and catalytic activities across vast compositional spaces, dramatically accelerating the discovery of novel materials [27].

Complex System Design: The discovery of unusual Sabatier behavior in high-entropy alloys with Gaussian-distributed adsorption energies opens new pathways for circumventing traditional scaling relationships [25]. This approach leverages spatial heterogeneity and spillover effects to achieve activities beyond conventional volcano plot limitations.

Multi-Descriptor Frameworks: As catalytic systems grow in complexity, single-descriptor analysis becomes increasingly limited. Future methodologies will likely employ multiple complementary descriptors that capture electronic, geometric, and environmental factors, providing more comprehensive activity predictions [26].

Cross-Disciplinary Applications: The demonstration of Sabatier principle governance in biocatalytic systems [29] suggests broader applicability across chemical domains, potentially enabling unified design strategies for heterogeneous, homogeneous, and enzymatic catalysis.

In conclusion, the d-band center provides the crucial electronic structure link that quantifies the century-old Sabatier principle, enabling predictive catalyst design through volcano plot relationships. This theoretical framework continues to evolve through integration with computational screening, advanced materials synthesis, and cross-disciplinary applications, offering powerful tools for addressing global energy and sustainability challenges through catalytic innovation.

From Theory to Practice: Calculating and Applying the d-Band Center

The d-band center theory stands as a foundational pillar in modern heterogeneous catalysis research, providing a powerful framework for understanding and predicting the catalytic activity of transition metal surfaces. First introduced by Hammer and Nørskov, this theory elegantly bridges the electronic structure of catalysts with their surface reactivity by establishing a direct correlation between the d-band center position and adsorption properties of intermediate species [2] [15]. At its core, the theory posits that the energy position of the d-band center relative to the Fermi level dictates the strength of adsorbate-surface interactions, which ultimately governs catalytic efficiency [15]. For transition metal catalysts, this descriptor has proven invaluable in rational catalyst design, enabling researchers to systematically engineer materials with optimized binding energies for target reactions.

The profound significance of the d-band center extends across diverse catalytic applications, from traditional thermal catalysis to electrocatalysis. In thermal catalysis, the d-band center helps explain trends in activity across transition metal series, while in electrocatalysis, it informs the design of advanced materials for energy conversion processes [2]. More recently, the d-band center has emerged as a crucial descriptor in machine learning pipelines for high-throughput catalyst screening, dramatically accelerating the discovery of novel catalytic materials by reducing reliance on computationally expensive simulations [27]. This theoretical framework has become particularly indispensable for designing non-precious metal catalysts, where electronic structure modulation offers a pathway to achieve performance metrics rivaling those of noble metal-based systems [18].

Theoretical Foundation

Fundamental Principles of the d-Band Model

The theoretical underpinnings of the d-band center model originate from the Newns-Anderson model and effective medium theory, which collectively describe the interaction between adsorbate states and metal surface orbitals [15]. According to the conventional d-band model, when an adsorbate approaches a transition metal surface, its molecular orbitals interact with the broad sp-band and the more localized d-states of the metal. While the sp-band contributes to a relatively constant binding energy background, the d-states generate distinctive bonding and antibonding states whose occupancy and energy separation determine the ultimate adsorption strength [15].

The model simplifies the complex density of d-states by representing it with a single energy value—the d-band center (εd)—defined as the first moment of the d-projected density of states (PDOS) relative to the Fermi level. A key predictive principle emerges: surfaces with higher d-band center positions (closer to the Fermi level) exhibit stronger adsorbate binding, while those with lower d-band centers (further from the Fermi level) demonstrate weaker interactions [15]. This relationship arises because an upward-shifted d-band center generates higher-lying antibonding states that remain less occupied, resulting in reduced Pauli repulsion and consequently stronger adsorption. This fundamental insight provides researchers with a powerful electronic descriptor for catalyst design, enabling predictive control over surface reactivity.

Advanced Theoretical Considerations: Spin Polarization Effects

While the conventional d-band model provides excellent correlations for numerous systems, its limitations become apparent when dealing with magnetically polarized transition metal surfaces such as Fe, Co, and Ni [15]. For these systems, a more sophisticated spin-polarized d-band center model is necessary to accurately capture surface-adsorbate interactions. In this generalized framework, the spin-averaged d-band center is replaced by two distinct centers: one for majority spin (εd↑) and another for minority spin (εd↓) [15].

Under spin polarization, these centers shift in opposite directions relative to the non-magnetic case, with εd↑ moving downward and εd↓ moving upward in energy. This separation creates a spin-dependent reactivity profile where minority and majority spin channels contribute asymmetrically to adsorption bonds [15]. For instance, on ferromagnetic Fe surfaces, only minority spin electrons participate significantly in H2 bond formation, resulting in weaker metal-hydrogen binding compared to antiferromagnetic configurations where both spin channels contribute equally [15]. This refined model successfully explains anomalous adsorption trends across the 3d transition metal series that the conventional model fails to capture, particularly for early transition metals with high spin polarization such as Mn and Fe [15].

Table 1: Key Theoretical Models for d-Band Center Analysis

| Model | Fundamental Principle | Applicability | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional d-Band Model | Single d-band center position predicts adsorption strength | Non-magnetic metals, noble metals, nearly-filled d-band systems | Fails for highly spin-polarized surfaces |

| Spin-Polarized d-Band Model | Separate d-band centers for majority and minority spin channels | Magnetic transition metals (Fe, Co, Ni, Mn) | Increased computational complexity |

| Generalized d-Band Center | d-band center normalized by coordination number | Nanoparticles, low-symmetry surfaces | Requires additional structural parameters |

Computational Methodology

Workflow for d-Band Center Calculation

The calculation of d-band centers follows a systematic computational workflow that integrates first-principles simulations with electronic structure analysis. The standardized procedure ensures consistent, reproducible results across different material systems and research groups. Below is a comprehensive overview of the key stages in this methodology:

Structure Preparation initiates the workflow with the construction of atomic models representing the catalytic surface of interest. For surface calculations, this typically involves creating slab models with sufficient vacuum layers to eliminate spurious interactions between periodic images [30]. The convergence testing of parameters such as k-point mesh density, plane-wave cutoff energy, and slab thickness is essential at this stage to ensure accuracy without excessive computational cost.

The DFT Calculation phase employs quantum mechanical simulations to solve for the electronic structure of the prepared system. The Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) represents one of the most widely utilized software packages for this purpose, though other DFT codes with plane-wave basis sets are equally applicable [30]. Critical considerations during this phase include the selection of appropriate exchange-correlation functionals (e.g., PBE, RPBE), inclusion of van der Waals corrections for weakly bonded systems, and for magnetic materials, implementation of spin-polarized calculations [30] [15].