Adsorption and Transition State Energy Relationships: From Fundamental Theory to Advanced Applications in Catalysis and Drug Design

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical relationship between adsorption energy and transition state energy, a cornerstone concept in chemical kinetics with profound implications for catalyst and drug...

Adsorption and Transition State Energy Relationships: From Fundamental Theory to Advanced Applications in Catalysis and Drug Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical relationship between adsorption energy and transition state energy, a cornerstone concept in chemical kinetics with profound implications for catalyst and drug design. We explore the foundational principles of Transition State Theory and the thermodynamic definition of adsorption energy, establishing how their interplay dictates reaction rates and pathways. The scope extends to a detailed examination of both traditional computational methods, like Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) and the Dimer method, and cutting-edge machine learning approaches for predicting transition states and adsorption energies. We address common challenges in computational workflows, including data scarcity and convergence issues, and present benchmarking strategies for validating results against experimental data. Aimed at researchers and professionals in catalysis and pharmaceutical development, this review synthesizes theoretical insights, methodological advances, and practical troubleshooting to guide the rational design of molecules and materials with tailored reactivity.

Core Concepts: Unraveling the Energetic Link Between Adsorption and the Transition State

Transition State Theory (TST), also referred to as activated-complex theory or absolute-rate theory, provides a fundamental framework for understanding and calculating the rates of elementary chemical reactions [1]. Developed simultaneously in 1935 by Henry Eyring at Princeton University and by Meredith Gwynne Evans and Michael Polanyi at the University of Manchester, TST represents a significant advancement over the earlier empirical Arrhenius rate law by incorporating mechanistic considerations of how reactions occur at the molecular level [1]. The theory has proven particularly valuable in qualitative understanding of chemical reactions and in calculating thermodynamic activation parameters (ΔG‡, ΔH‡, ΔS‡) when experimental rate constants are available [1].

In the context of adsorption energy and transition state energy relationships, TST provides the critical link between the thermodynamic strength of surface adsorption and the kinetic rates of catalytic transformations. This connection is essential for research aimed at designing improved catalysts and optimizing reaction conditions in heterogeneous catalysis and drug development [2] [3]. For researchers investigating molecular interactions at surfaces, TST offers both a conceptual model and quantitative tools for relating the energy landscape of reactions to their observable rates.

Theoretical Foundations of TST

Core Principles and Basic Equations

Transition State Theory is built upon several key postulates about the behavior of reacting systems. The theory assumes that during the conversion of reactants to products, molecular systems must pass through a special high-energy configuration known as the transition state or activated complex [1] [2]. This transition state represents the point of highest potential energy along the minimum energy pathway connecting reactants and products. A second fundamental assumption is that the activated complexes are in a special quasi-equilibrium with the reactant molecules, distinct from the overall equilibrium between reactants and products [1]. Finally, TST assumes that the rate of the reaction is determined by the concentration of these transition state complexes multiplied by the frequency at which they convert to products [1].

The mathematical formulation of TST leads to the Eyring equation, which provides a theoretical expression for the reaction rate constant [2]:

Where:

kis the reaction rate constantk_Bis Boltzmann's constantTis absolute temperaturehis Planck's constantQ‡is the partition function of the transition stateQ_Ris the partition function of the reactantsΔG‡is the Gibbs free energy of activationRis the universal gas constant

The term k_BT/h represents the universal frequency of barrier crossing attempts, typically on the order of 10^12-10^13 s⁻¹ at room temperature [2]. The partition function ratio Q‡/Q_R relates to the probability of forming the transition state, while the exponential term describes the energy requirement for reaching the transition state.

Comparison with Arrhenius Theory

While the empirical Arrhenius equation (k = A × exp(-E_a/RT)) predates TST and was derived from experimental observations, the Eyring equation provides a theoretical foundation for both the pre-exponential factor A and the activation energy E_a [1] [2]. The Arrhenius activation energy E_a relates approximately to the enthalpy of activation (ΔH‡) in TST, while the pre-exponential factor A encompasses both the frequency factor k_BT/h and the entropy of activation (ΔS‡) through the relationship A ∝ (k_BT/h) × exp(ΔS‡/R) [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Arrhenius and Transition State Theory Parameters

| Parameter | Arrhenius Theory | Transition State Theory |

|---|---|---|

| Rate Constant | k = A × exp(-E_a/RT) |

k = (k_BT/h) × (Q‡/Q_R) × exp(-ΔG‡/RT) |

| Activation Energy | Empirical parameter E_a |

Related to enthalpy of activation ΔH‡ |

| Pre-exponential Factor | Empirical parameter A |

Related to entropy of activation (k_BT/h) × exp(ΔS‡/R) |

| Theoretical Basis | Empirical | Derived from statistical mechanics |

Potential Energy Surfaces and the Reaction Coordinate

The conceptual foundation of TST relies on the existence of a potential energy surface (PES) that describes how the energy of a molecular system changes with nuclear configuration [1]. The progress of a reaction can be visualized as a point moving across this multidimensional surface from the reactant valley to the product valley, necessarily passing through a saddle point known as the transition state [1]. The reaction coordinate represents the lowest-energy pathway connecting reactants and products through this transition state [2].

In 1931, Henry Eyring and Michael Polanyi constructed the first potential-energy surface for the reaction H + H₂ → H₂ + H, based on quantum-mechanical principles and experimental data [1]. This work established the importance of visualizing chemical reactions as motions on potential energy surfaces, with the transition state located at the saddle point or "col" between reactant and product basins [1].

Advanced Theoretical Developments

Limitations of Conventional TST and Modern Extensions

While conventional TST provides a powerful framework, it relies on several simplifying assumptions that limit its accuracy for certain systems. The theory assumes no recrossing of the transition state dividing surface—meaning that any system that reaches the transition state proceeds to products without turning back [2]. It also treats motion along the reaction coordinate classically, neglecting quantum mechanical effects such as tunneling through the energy barrier rather than passing over it [2]. Additionally, the quasi-equilibrium assumption between reactants and the transition state may break down for very fast reactions [2].

To address these limitations, several advanced theoretical extensions have been developed:

Variational Transition State Theory (VTST): This approach variationally optimizes the location of the dividing surface between reactants and products to minimize the flux of recrossing trajectories, thereby improving rate constant predictions [2] [4].

Variable Reaction Coordinate TST (VRC-TST): Specifically designed for barrierless reactions (such as radical recombinations), VRC-TST employs variable, multifaceted dividing surfaces to properly describe reactions without a well-defined saddle point [4].

Quantum Transition State Theory: Incorporates quantum mechanical effects such as tunneling, particularly important for reactions involving hydrogen transfer at low temperatures [2].

Dynamical Corrections to TST: Uses molecular dynamics simulations to calculate transmission coefficients that account for dynamical effects not captured by static TST [2].

NN-VRCTST: Machine Learning Enhanced TST

Recent advances have integrated artificial intelligence with TST to overcome computational bottlenecks. The NN-VRCTST approach fits the potential energy surface with physics-inspired artificial neural network (ANN) models to be used as surrogate potentials in VRC-TST simulations [4]. This method has demonstrated accuracy within 20% of traditional VRC-TST while reducing the number of required single-point energy evaluations by at least a factor of four [4]. The decoupling of ANN training from VRC-TST calculations enables optimization of computational resources and quality inspection of the data points used in the simulations [4].

Table 2: Advanced Transition State Theory Methodologies

| Methodology | Key Features | Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variational TST (VTST) | Variational optimization of dividing surface | Reactions with significant recrossing | Improved accuracy for recrossing-dominated reactions |

| Variable Reaction Coordinate TST (VRC-TST) | Variable dividing surfaces anchored on reactive centers | Barrierless reactions, radical recombinations | Accurate treatment of reactions without saddle points |

| Quantum TST | Incorporates quantum tunneling effects | Reactions involving H-atom transfer, low temperatures | Accounts for quantum mechanical effects |

| NN-VRCTST | Neural network potentials for PES | Complex barrierless reactions | Reduces computational cost by 4x while maintaining accuracy |

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Determining TST Rate Constants Using Quantum Chemistry

The application of Transition State Theory to predict reaction rates typically follows a well-defined computational workflow that combines quantum chemistry calculations with kinetic theory. A representative methodology for determining TST rate constants involves several key steps [5]:

System Selection and Reaction Mechanism Definition: Identify the elementary reaction steps and define the stoichiometry. For example, in studying mercury oxidation in combustion systems, researchers defined an 8-step mechanism involving reactions with Cl, Cl₂, HCl, and HOCl species [5].

Quantum Chemistry Calculations: Perform high-level quantum chemistry calculations using software such as Gaussian 03W to determine molecular structures, vibrational frequencies, and energies of reactants, products, and transition states [5]. These calculations typically employ:

- Electron correlation methods (e.g., MP2, CCSD(T))

- Appropriate basis sets with polarization and diffuse functions

- Effective core potentials (ECP) for heavy elements

Transition State Validation: Validate the identified transition state by confirming that it has exactly one imaginary vibrational frequency (negative eigenvalue in the Hessian matrix) corresponding to motion along the reaction coordinate [5].

Rate Constant Calculation: Apply the appropriate TST formulation based on reaction type. For bimolecular reactions, conventional TST (CTST) takes the form [5]:

Where

Lis a statistical factor,Q_TS,Q_A,Q_Bare partition functions for the transition state and reactants, andE_0is the barrier height.RRKM Theory for Unimolecular Reactions: For unimolecular decomposition reactions, employ Rice-Ramsperger-Kassel-Marcus (RRKM) theory with variational transition state theory to locate the transition state along the reaction coordinate, particularly for barrierless reactions [5].

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Methods for TST Research

| Tool/Method | Function | Application in TST Research |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software (Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem) | Performs electronic structure calculations | Determines molecular geometries, energies, and vibrational frequencies of reactants and transition states [5] |

| Potential Energy Surface Scanners | Maps multidimensional energy landscapes | Locates transition states and minimum energy paths for reactions [1] [4] |

| Partition Function Calculators | Computes statistical mechanical properties | Evaluates translational, rotational, and vibrational partition functions for TST rate expressions [5] |

| Variational TST Implementations (VaReCoF, PolyRate) | Performs advanced TST calculations | Handles barrierless reactions and optimizes dividing surfaces [4] |

| Machine Learning Potentials (NN-VRCTST) | Accelerates PES evaluation | Reduces computational cost of high-level TST calculations [4] |

| High-Performance Computing Clusters | Provides computational resources | Enables demanding quantum chemistry and dynamics simulations [4] |

Applications in Adsorption Energy and Catalysis Research

Connecting Adsorption Energies to Transition State Energies

In heterogeneous catalysis, Transition State Theory provides the critical framework linking adsorption energies to reaction rates—a relationship central to catalyst design and optimization. Density functional theory (DFT) predictions of binding energies and reaction barriers provide invaluable data for analyzing chemical transformations in heterogeneous catalysis [3]. The accuracy of these predictions directly impacts the reliability of computed reaction rates through TST.

The challenge in this field lies in achieving a balanced description of both strong covalent interactions and weaker non-covalent (dispersion) interactions on transition metal surfaces [3]. Different exchange-correlation functionals (such as BEEF-vdW, RPBE, MS2, SCAN) show varying performance for different types of adsorption, with no single functional currently providing optimal accuracy for all systems [3]. For instance, in methanol decomposition on Pd(111) and Ni(111), different functionals (optB86b-vdW, PBE+D3, PBE) show dramatically varying accuracy depending on the specific reaction step, highlighting the complexity of achieving balanced accuracy [3].

Recent approaches combining periodic DFT calculations with higher-level quantum chemical corrections on cluster models have shown promise in improving the accuracy of adsorption energies and activation barriers [3]. For example, applying corrections from higher-level calculations to small metal clusters can improve periodic band structure adsorption energies and barriers, with demonstrated mean absolute errors of 2.2 kcal mol⁻¹ for covalent adsorption, 2.7 kcal mol⁻¹ for non-covalent adsorption, and 1.1 kcal mol⁻¹ for activation barriers [3].

Case Study: Mercury Oxidation in Combustion Systems

A practical application of TST in environmental chemistry involves predicting the rate constants for mercury oxidation in combustion systems [5]. Researchers applied quantum chemistry and TST to determine rate constants for eight Hg-Cl reaction steps in the temperature range of 298-2000 K [5]. The methodology involved:

- Using high-level quantum chemistry calculations with effective core potential basis sets for Hg and all-electron basis sets with polarization and diffuse functions for Cl/O/H species [5].

- Validating computational methods by comparing calculated molecular structures, vibrational frequencies, and reaction enthalpies with reliable reference data [5].

- Applying conventional TST for bimolecular reactions and RRKM theory for atom-atom recombination reactions [5].

- Determining that Hg/HgCl recombination reactions with Cl were the fastest mercury-chlorine reactions, while Hg/HgCl reactions with HCl were the slowest, providing mechanistic insight into mercury oxidation pathways [5].

This application demonstrates how TST enables predictions of environmentally important reaction rates that would be challenging to measure experimentally across all relevant conditions.

Future Perspectives and Research Directions

The continued evolution of Transition State Theory is marked by several promising research directions. The integration of machine learning approaches, as demonstrated by NN-VRCTST, is likely to expand to more complex reaction systems, potentially enabling accurate rate predictions for reactions involving large molecular systems or complex interfaces [4]. The development of multiscale modeling strategies that combine high-level electronic structure methods, efficient TST implementations, and microkinetic modeling will further enhance our ability to predict reaction rates across diverse chemical environments [5] [3].

For researchers focused on adsorption energy and transition state energy relationships, ongoing efforts to improve the accuracy of density functionals for both strong covalent and weak non-covalent interactions will be crucial [3]. The combination of periodic DFT with wavefunction-based corrections for cluster models represents a promising path toward achieving chemical accuracy (errors < 1 kcal/mol) in adsorption and activation energies [3].

As these methodological advances continue, Transition State Theory will maintain its central role in connecting molecular-level interactions to macroscopic reaction rates, enabling more rational design of catalysts and optimization of reaction conditions in fields ranging from industrial catalysis to pharmaceutical development.

Adsorption energy is a fundamental thermodynamic descriptor that quantifies the interaction strength between an adsorbate (a molecule, atom, or ion) and a surface. This parameter is critical for understanding and predicting the behavior of materials across a vast range of technologies, including catalysis, gas separation, sensors, and drug development [6] [7]. The significance of adsorption energy extends beyond equilibrium properties to the kinetics of surface processes, as it shares an intimate relationship with the energy of transition states in catalytic reactions [1] [8]. A precise definition and reliable methods for determining adsorption energy are therefore foundational to research aimed at designing new functional materials.

This article provides an in-depth technical guide to the conceptual definition, computational and experimental determination, and thermodynamic significance of adsorption energy, with particular emphasis on its role in transition state theory and reaction kinetics.

Fundamental Definition and Thermodynamic Formulation

Conceptual Definition

Adsorption energy (ΔEads) is fundamentally defined as the energy change associated with the process of a molecule (the adsorbate) binding to a surface (the adsorbent). A negative adsorption energy indicates an exothermic, favorable process. The strength of this interaction dictates key properties such as surface coverage, adsorbate stability, and the facility of subsequent surface reactions [6].

Quantitative Formulation

The standard quantum-mechanical expression for calculating adsorption energy is given by:

ΔEads = Esys - Eslab - Egas [6]

Where:

- ΔEads is the adsorption energy.

- Esys is the total energy of the combined adsorbate-surface system in its relaxed, minimum-energy configuration.

- Eslab is the energy of the clean, relaxed surface (slab) without the adsorbate.

- Egas is the energy of the isolated, gas-phase adsorbate molecule.

Table 1: Components of the Adsorption Energy Equation.

| Symbol | Quantity | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Esys | System Energy | Total energy of the relaxed adsorbate-surface complex |

| Eslab | Slab Energy | Energy of the pristine, relaxed surface structure |

| Egas | Gas Phase Energy | Energy of the adsorbate molecule in its isolated state |

This deceptively simple formula necessitates accurate calculations of its constituent terms. The critical step is identifying the global minimum-energy configuration for the adsorbate-surface system (Esys), which involves exploring numerous potential binding sites and molecular orientations [6]. Furthermore, the reference states must be carefully considered; for instance, the energy of the clean surface (Eslab) should be structurally consistent with the surface in the adsorbed state to avoid artifacts [9].

Computational Determination of Adsorption Energy

Computational methods, particularly first-principles calculations based on Density Functional Theory (DFT), are the most common tools for predicting adsorption energies. These methods enable researchers to model interactions at the atomic scale and screen large numbers of materials in silico [6] [7].

Workflow for Accurate Computational Determination

A robust computational protocol for determining adsorption energy involves several key stages, as visualized below.

Diagram 1: Workflow for computational determination of adsorption energy. ML: Machine Learning.

Step 1: Surface and Adsorbate Preparation. The catalyst surface is modeled as a periodic slab, and its geometry is fully relaxed to a minimum energy state to establish the reference Eslab. The gas-phase adsorbate is also optimized to obtain Egas [6].

Step 2: Configuration Sampling. Multiple initial adsorbate-surface configurations are generated. This can be based on heuristic methods (e.g., high-symmetry sites) or stochastic sampling to ensure comprehensive exploration of the potential energy surface (PES) [10] [6]. For complex or flexible molecules, this step is critical.

Step 3: Structure Relaxation. Each initial configuration is relaxed to its nearest local energy minimum. While DFT is the standard for final accuracy, the process is computationally expensive. Machine learning potentials (MLPs) are increasingly used for pre-screening, performing relaxations ~2000 times faster to identify promising candidate structures for subsequent DFT refinement [6].

Step 4: Energy Calculation and Validation. After identifying the global minimum configuration (lowest Esys), the adsorption energy is calculated. The final structure must be validated to ensure the adsorbate is not desorbed or dissociated, which would render the result invalid [6].

Advanced and High-Throughput Approaches

The computational field is rapidly evolving toward high-throughput screening. The Open DAC 2025 (ODAC25) dataset exemplifies this, comprising nearly 70 million DFT calculations for gas adsorption in metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [9]. Tools like Xsorb automate the sampling and optimization process for finding the most stable adsorption configuration [10]. Furthermore, hybrid algorithms like AdsorbML leverage machine learning to achieve a spectrum of accuracy-efficiency trade-offs, dramatically accelerating the discovery of low-energy adsorbate configurations [6].

Experimental Methodologies for Measuring Adsorption Energy

Experimental validation is essential to complement computational predictions. Several techniques can be used to probe adsorption energies, each with its own methodology and scope.

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for Adsorption Energy Determination.

| Technique | Core Principle | Measurable Parameters | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reversed-Flow Gas Chromatography (RF-GC) [11] | Measures perturbations in analyte retention caused by adsorption/desorption on a solid stationary phase. | Adsorption isotherms, probability density functions for adsorption energies, lateral interaction energies. | Suitable for characterizing heterogeneous solid surfaces under conditions near atmospheric. |

| Scanning Kelvin Probe (SKP) [12] | Measures contact potential difference, related to work function changes induced by adsorbate bonding. | Relative changes in adsorption energy trends, metal-hydrogen bond energy. | Operates at solid/liquid interfaces; provides indirect energy estimates based on electronic structure changes. |

| Temperature-Programmed Desorption (TPD) | Monitors desorption rate of an adsorbate as temperature is linearly increased. | Desorption activation energy, which relates to the adsorption strength. | A well-established technique not featured in the search results but widely used in the field. |

Detailed Protocol: Reversed-Flow Gas Chromatography

RF-GC is a powerful method for measuring adsorption energies on heterogeneous surfaces, as it can determine energy distributions and lateral molecular interactions [11].

1. Apparatus and Materials:

- Chromatograph: Equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID).

- Sampling Column: Packed with the solid adsorbent of interest (e.g., calcium oxide, 10-30 mesh).

- Carrier Gas: Ultra-high-purity nitrogen.

- Analytes: Pure samples of the adsorbate molecules (e.g., hydrocarbons C2-C4).

2. Experimental Procedure:

- The sampling column containing the solid adsorbent is placed in the chromatograph oven.

- A small amount of the adsorbate vapor is injected into the carrier gas stream.

- The flow direction is periodically reversed. The resulting chromatographic peaks ("sample peaks") are recorded as a function of time.

- The height (H) of these sample peaks and their corresponding time (t) are the primary raw data [11].

3. Data Analysis and Calculations:

- The peak heights and times are fitted to an equation of the form: H1/M = Σ Ai exp(Bit), where M is the detector response factor, and Ai and Bi are fitting coefficients [11].

- From the pre-exponential factors and exponential coefficients, physicochemical quantities are extracted using specialized software (e.g., a "LAT PC program"). These include the adsorption energy (ε), local adsorption isotherm, local monolayer capacity, and a parameter (β) characterizing lateral interactions between adsorbed molecules [11].

The Thermodynamic Link to Transition State Theory

The thermodynamic significance of adsorption energy is profoundly linked to the kinetics of surface reactions through Transition State Theory (TST). TST explains reaction rates by positing that reactants form an activated transition state complex, which is in quasi-equilibrium with the reactants [1].

The Role of Adsorption in Catalytic Cycles

In a catalytic reaction, the adsorption of reactants is the first critical step. The adsorption energy of a reaction intermediate is a powerful descriptor for catalytic activity, embodying the Sabatier principle: the optimal catalyst binds reactants neither too strongly nor too weakly [12]. For instance, in the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), the adsorption energy of the hydrogen intermediate (M-H) directly correlates with the reaction rate [12].

Adsorption Energy and Activation Barriers

The energy required to form the transition state is intrinsically linked to the stability of the adsorbed initial state. This connection is formalized in the Eyring equation, derived from TST, which expresses the reaction rate constant as: k = (kBT / h) exp(-ΔG‡ / RT)

Here, ΔG‡ is the standard Gibbs energy of activation, which is the difference in free energy between the transition state and the reactants [1]. The adsorption energy directly influences the initial state energy, thereby affecting ΔG‡. This relationship is leveraged in studies of surface reactions, such as the adsorption and desorption of acetone on TiO2 clusters, where the Gibbs free energy of adsorption is a key input for applying TST to calculate desorption rates and sensor recovery times [8].

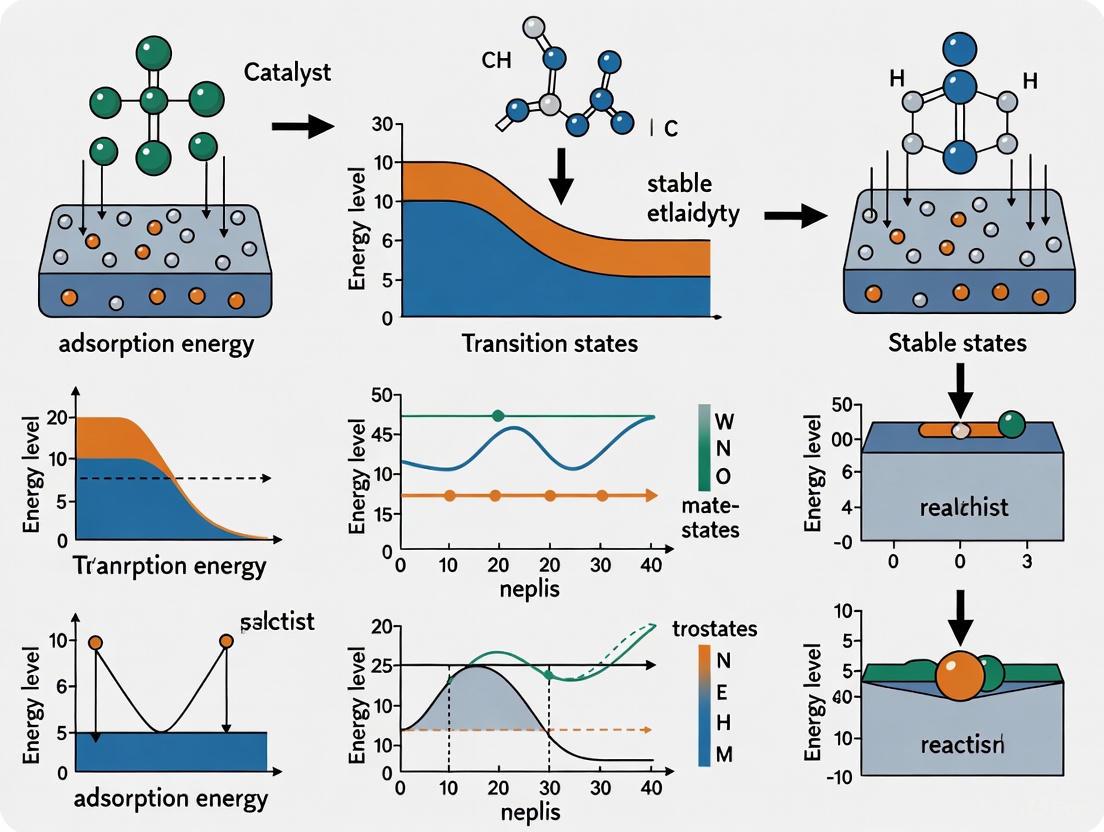

The following diagram illustrates the energetic pathway of a surface reaction, highlighting the central role of adsorption energy.

Diagram 2: Energetic pathway of a catalytic surface reaction, showing the relationship between adsorption energy (ΔEads) and the activation barrier (ΔG‡). The diagram shows how the adsorption energy of the initial state sets the baseline for the activation barrier of the subsequent surface reaction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This section details key computational and experimental resources essential for research in adsorption science.

Table 3: Key Resources for Adsorption Energy Research.

| Category / Name | Function / Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Software & Databases | ||

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) [6] [7] | First-principles method for computing electronic structure, energies, and forces of atomistic systems. | Gold standard for calculating accurate adsorption energies; used in codes like Quantum ESPRESSO [10]. |

| Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) [9] [6] | ML models (e.g., EquiformerV2) trained on DFT data to predict energies/forces at a fraction of the cost. | High-throughput pre-screening of adsorption configurations; implemented in tools like AdsorbML [6]. |

| iRASPA [13] | GPU-accelerated visualization software for materials science. | Visualizing crystal structures (MOFs, zeolites), adsorption sites, and energy surfaces. |

| Xsorb [10] | Python-based program that automates sampling of adsorption configurations on crystal surfaces. | Identifying the most stable adsorption geometry and energy for molecule-surface systems. |

| Experimental Materials & Tools | ||

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [9] | Highly tunable, porous crystalline materials with vast surface areas. | Promising sorbents for direct air capture (DAC) and gas separation; subject of high-throughput screening. |

| Transition Metal Dichalcogenides (TMDs) [7] | Two-dimensional (2D) materials like MoS₂ and WSe₂. | Model systems for studying adsorption and defect chemistry in memristors and catalysis. |

| Reversed-Flow GC Setup [11] | Specialized gas chromatograph with flow reversal capabilities and FID detection. | Experimental determination of adsorption energy distributions and isotherms on solid powders. |

Adsorption energy, rigorously defined by the energy difference ΔEads = Esys - Eslab - Egas, is a cornerstone property for the design and understanding of functional materials. Its accurate determination, whether through sophisticated computational workflows combining DFT and machine learning or through meticulous experimental techniques like reversed-flow gas chromatography, remains an active and evolving field of research. The thermodynamic significance of adsorption energy is profoundly amplified by its direct connection to the activation energies that govern surface reaction kinetics, as described by Transition State Theory. A deep understanding of this relationship, encapsulated by the Sabatier principle, enables the rational design of catalysts, sorbents, and sensors, guiding researchers in selecting and optimizing materials for enhanced performance across chemical engineering, materials science, and drug development.

In computational catalysis and materials science, the concept of the energy landscape provides a fundamental framework for understanding and predicting the rates and selectivity of surface reactions. At the heart of this landscape lies a critical relationship: the strength with which adsorbates bind to a catalyst surface directly influences the geometry and energy of transition states—the highest-energy configurations along reaction pathways. This intimate connection between adsorption strength and transition state geometry serves as a cornerstone for rational catalyst design, enabling researchers to predict catalytic activity without exhaustive experimental screening.

The theoretical foundation for this relationship rests on unifying principles such as the Brønsted-Evans-Polanyi (BEP) relations and the d-band model, which correlate adsorption energies with activation barriers across diverse catalytic systems [14] [15]. As this whitepaper will demonstrate, adsorption energy functions as a powerful descriptor that efficiently correlates with catalytic activity and selectivity by dictating how reaction intermediates and transition states interact with catalyst surfaces [16] [14]. Through detailed case studies and computational methodologies, we explore how atomic-scale surface chemistry governs macroscopic kinetic observables across heterogeneous catalysis, energy storage, and electronic device applications.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Principles

Electronic Structure Descriptors of Adsorption Strength

The electronic structure of a catalyst surface fundamentally determines its interaction with adsorbates. Among various theoretical frameworks, the d-band model has emerged as a particularly effective descriptor for predicting adsorption energies and, by extension, transition state geometries. This model quantifies adsorption behavior by treating the d-band center (the average energy of the d-band states) as a key parameter [14]. When the d-band center shifts closer to the Fermi level, the anti-bonding states formed between the surface and adsorbate become partially filled, resulting in stronger adsorption (more negative adsorption energy) [14]. This electronic principle provides a powerful predictive capability: a decrease in the number of valence electrons correlates with a positive shift in the d-band structure, strengthening adsorption interactions and subsequently influencing transition state configurations.

Complementing the d-band model, the Friedel model offers additional insights through the parabolic relationship between sublimation energy and the number of valence electrons [14]. These electronic descriptors enable researchers to establish structure-property-performance relationships that guide catalyst development without requiring exhaustive computational screening of every possible material composition.

Correlation Between Adsorption Energy and Transition State Energy

The intrinsic link between adsorption energy and transition state energy finds its theoretical basis in linear free energy relationships, most notably the Brønsted-Evans-Polanyi (BEP) relations [15]. These principles establish that the transition state energy of an elementary reaction step correlates linearly with the adsorption energy of its reaction intermediates. This relationship emerges because transition states often resemble reaction products or intermediates in their bonding configuration with the catalyst surface.

The practical implication of this correlation is profound: adsorption energies can serve as effective descriptors for predicting catalytic activity across diverse reactions [14]. According to the Sabatier principle, optimal catalysts exhibit moderate adsorption energies—strong enough to activate reactants but weak enough to allow product desorption [14]. This principle generates characteristic "volcano plots" where catalytic activity reaches a maximum at intermediate adsorption strengths, highlighting how adsorption energy directly influences the overall reaction kinetics through its effect on transition state energies.

Quantitative Relationships: Experimental and Computational Evidence

Adsorption Energy Trends Across Material Systems

Table 1: Measured Adsorption Energies of Selected Adatom-TMD Systems

| Adsorbate | TMD Substrate | Adsorption Energy (eV) | Charge Transfer ( | e | ) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold (Au) | MoS₂ | -2.64 | ~0.5 | [7] | ||

| Silver (Ag) | MoS₂ | -2.19 | ~0.3 | [7] | ||

| Copper (Cu) | MoS₂ | -2.96 | ~0.6 | [7] | ||

| Scandium (Sc) | MoS₂ | -5.57 | >1.0 | [7] | ||

| Yttrium (Y) | MoS₂ | -5.83 | >1.0 | [7] | ||

| Hydrogen (H₂) | SnS₂ | -0.049 to -0.063 | Minimal | [17] | ||

| Hydrogen (H₂) | S-vacancy SnS₂ | -0.086 | Significant | [17] |

The data in Table 1 reveals fundamental trends in adsorption energetics. For transition metal adsorbates on TMDs, early transition metals (Sc, Y) exhibit unexpectedly weaker adsorption energies despite greater charge transfer, while middle transition metals (Ti, Zr, Hf) show stronger adsorption interactions [7]. This indicates that charge transfer alone cannot fully describe adsorption behavior; the ability of the adsorbate to hybridize effectively with the substrate plays a crucial role in determining adsorption strength. Metals with fully filled d-orbitals (Zn, Cd, Hg) consistently display the weakest adsorption energies, sometimes even positive values, reflecting their limited hybridization capability [7].

Adsorption-Transition State Relationships in Catalytic Reactions

Table 2: Adsorption Energy Effects on Reaction Kinetics in Selected Systems

| Reaction System | Key Finding | Impact on Activation Barrier | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| NH₃ decomposition on Pt(100) vs Pt(111) | Pt(100) has superior activity due to lower barriers | Reduced barriers on Pt(100) surface | [18] |

| H₂ adsorption on pristine vs defective SnS₂ | S-vacancy increases adsorption energy by ~70% | Not measured directly | [17] |

| Co-adsorbed H on Pt(111) | Inhibits NH₃ decomposition at high coverage | Significant barrier increase on Pt(111) | [18] |

| Co-adsorbed H on Pt(100) | Minimal impact on NH₃ decomposition | Stable reaction energetics | [18] |

The structure-sensitivity of adsorption-strength relationships emerges clearly from comparative studies. For ammonia decomposition, Pt(100) facets maintain stable reaction energetics even under high hydrogen coverage, while Pt(111) facets exhibit significant inhibition with increased reaction barriers and destabilized intermediates [18]. This facet-dependent behavior demonstrates how transition state geometry responds differently to adsorption strength variations depending on the atomic arrangement of the catalyst surface. The identification of N-N coupling and N₂ desorption as rate-limiting steps further highlights how specific elementary reactions exhibit distinct sensitivities to adsorption strength variations [18].

Diagram 1: Transition State Evolution with Adsorption Strength. The diagram illustrates how transition state geometry shifts from early (reactant-like) to late (product-like) configurations as adsorption strength increases, following the Bell-Evans-Polanyi principle.

Computational Methodologies for Characterizing Energy Landscapes

First-Principles Density Functional Theory

Density Functional Theory (DFT) serves as the foundational computational method for calculating adsorption energies and mapping transition state geometries at the atomic scale. Modern DFT protocols employ carefully parameterized exchange-correlation functionals to balance accuracy with computational feasibility:

Van der Waals Corrections: For systems dominated by weak interactions, such as H₂ adsorption on SnS₂, the revPBE-vdW functional explicitly includes dispersion forces [17]. This approach yields adsorption energies in the range of -49 to -63 meV for H₂ on pristine SnS₂, increasing to approximately -86 meV for sulfur-deficient surfaces [17].

Spin-Polarized Calculations: Magnetic elements (Fe, Co, Ni, etc.) require spin-polarized DFT to accurately capture their electronic structure and adsorption properties [15]. The AQCat25 dataset represents a significant advancement in this regard, incorporating spin polarization for magnetic systems to improve prediction fidelity [15].

Plane-Wave Basis Sets: Typical calculations employ plane-wave cutoffs of 500-650 eV with projector augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials to describe electron-ion interactions [17] [15]. Brillouin zone integration uses Monkhorst-Pack k-point grids, typically 4×4×1 for 2D materials, with convergence thresholds of 10⁻⁵ eV for energy and 0.01 eV/Å for forces [17].

Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials

The computational expense of DFT has motivated development of Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) that approach quantum accuracy at significantly reduced cost. Frameworks like CatBench systematically benchmark MLIP performance across diverse adsorption reactions, with best-performing models achieving ~0.2 eV accuracy in adsorption energy predictions [16]. Universal MLIPs trained on massive datasets (e.g., the Open Catalyst Project's nearly 300 million DFT calculations) enable large-scale screening of catalyst materials while maintaining transferability across chemical space [15].

Recent multi-fidelity approaches integrate limited high-fidelity data (including spin polarization) with larger lower-fidelity datasets, achieving accuracy comparable to single-fidelity models with eight times less costly high-fidelity data [15]. These advances address critical gaps in previous datasets, particularly for industrially relevant catalytic processes involving earth-abundant first-row transition metals that exhibit strong spin polarization effects [15].

Microkinetic Modeling and Kinetic Monte Carlo

Connecting atomic-scale adsorption energetics to macroscopic reaction rates requires microkinetic modeling based on DFT-calculated parameters. For complex systems like NH₃ decomposition on Pt surfaces, this approach reveals how co-adsorbed hydrogen species inhibit reaction kinetics by increasing activation barriers and destabilizing intermediates [18].

Kinetic Monte Carlo (kMC) simulations extend this capability by modeling stochastic processes of adsorption, desorption, and surface diffusion. For H₂ adsorption on SnS₂, kMC implementations utilize desorption energies equal to the negative of adsorption energies and diffusion barriers derived from transition state theory [17]. These simulations track surface coverage evolution under varying temperature and pressure conditions, providing insights into operational performance under realistic environments.

Case Studies in Applied Systems

Resistive Switching in Transition Metal Dichalcogenides

In non-volatile resistive switching (NVRS) devices based on monolayer TMDs (MoS₂, MoSe₂, WS₂, WSe₂), adsorption and desorption of metal adatoms modulate resistivity through point defect formation and dissolution [7]. The adsorption energy of transition metal adatoms (Au, Ag, Cu) onto chalcogen vacancies directly correlates with switching energy—the energy required to change the resistive state of the device [7]. First-principles calculations reveal consistent periodic trends across TMDs, with adsorption energies following the order Cu (-2.96 eV) > Au (-2.64 eV) > Ag (-2.19 eV) on MoS₂ [7]. This structure-property relationship enables rational selection of TMD-adsorbate pairs to optimize NVRS device performance for next-generation computing technologies.

Hydrogen Storage and Sensing Applications

Two-dimensional SnS₂ exhibits promising characteristics for hydrogen storage applications, with vdW-DFT calculations revealing adsorption energies of -49 to -63 meV on pristine surfaces [17]. While these weak interactions limit storage capacity at room temperature, sulfur vacancies increase adsorption energies to approximately -86 meV through enhanced charge transfer and orbital hybridization [17]. The repulsive interaction between adjacent H₂ molecules further limits surface coverage, presenting both challenges and opportunities for material design. Kinetic Monte Carlo simulations built on DFT parameters enable prediction of coverage dynamics under operational temperature and pressure conditions, guiding material optimization for practical storage applications [17].

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Adsorption and Transition State Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Implementation | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT Codes | VASP [17] [15] | Electronic structure calculation | Adsorption energy computation |

| Quantum ESPRESSO [19] | DFT with plane-wave basis | Drug-nanoparticle interactions | |

| Machine Learning Potentials | CatBench [16] | MLIP benchmarking | Adsorption energy prediction |

| Universal Model for Atoms (UMA) [15] | Multi-task surrogate modeling | Catalyst restructuring effects | |

| Catalysis Databases | Catalysis-hub.org [14] | Adsorption energy repository | Transition metal screening |

| AQCat25 Dataset [15] | Spin-polarized reference data | Magnetic catalyst modeling | |

| Analysis Tools | Bader Charge Analysis [7] [17] | Electron partitioning | Charge transfer quantification |

| Microkinetic Modeling [18] | Reaction kinetics simulation | NH₃ decomposition pathways |

Diagram 2: Integrated Workflow for Adsorption-Transition State Research. The diagram outlines the iterative computational and experimental pipeline for establishing adsorption-strength relationships, from first-principles calculations to experimental validation.

The fundamental relationship between adsorption strength and transition state geometry represents a unifying principle across diverse domains of materials science and catalysis. As demonstrated through the case studies presented herein, adsorption energy serves as a powerful descriptor for predicting and rationalizing catalytic activity, materials functionality, and device performance. The consistency of this relationship across different material systems—from transition metal catalysts to 2D materials—underscores its robustness as a design principle.

Future advances in this field will likely emerge from several key directions: (1) increased incorporation of high-fidelity electronic structure effects, particularly spin polarization, in machine learning potentials; (2) development of multi-scale modeling frameworks that connect atomic-scale adsorption phenomena to device-level performance; and (3) systematic experimental validation of predicted structure-property relationships across well-defined material systems. As computational methodologies continue evolving toward greater accuracy and efficiency, the fundamental principles governing adsorption strength and transition state geometry will remain essential for rational design of advanced materials and catalysts addressing pressing energy and technological challenges.

In synthetic chemistry and drug development, predicting and controlling the rate at which reactants convert into products is a fundamental challenge. The central concept governing this transformation is the activation energy (Ea), the energy barrier that must be overcome for a reaction to proceed [20]. Reaction kinetics provides the framework for quantifying this process, directly determining the feasibility, scalability, and efficiency of chemical syntheses, including the production of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). The empirical relationship between temperature and reaction rate was first captured by the Arrhenius equation, ( k = A e^{-E_a/RT} ), where ( k ) is the rate constant, ( A ) is the pre-exponential factor (or frequency factor), ( R ) is the universal gas constant, and ( T ) is the absolute temperature [1] [21]. A higher activation energy signifies a reaction rate that is more sensitive to temperature changes, a critical consideration for optimizing industrial and laboratory processes.

This guide explores the intrinsic connection between adsorption energy and transition state energy, a relationship pivotal for understanding and designing catalytic cycles in heterogeneous catalysis. The energy required for an adsorbate to bind to a catalyst surface directly influences the height of the energy barrier for the subsequent chemical transformation [3]. Recent advances in computational chemistry and high-temperature experimental techniques are now enabling researchers to access and manipulate reaction pathways previously considered inaccessible, thereby expanding the synthetic toolbox available to scientists [22] [3]. The following sections provide a detailed examination of the theoretical foundations, experimental protocols, and contemporary research frontiers that define this field.

Theoretical Foundations: From Arrhenius to Transition State Theory

While the Arrhenius equation successfully describes the temperature dependence of reaction rates, Transition State Theory (TST) provides a more profound physical interpretation of the parameters involved. TST posits that reactions proceed through a high-energy, quasi-equilibrium transition state (or activated complex) located at the saddle point of the potential energy surface connecting reactants to products [1] [21]. The formation of this transition state acts as the kinetic bottleneck for the reaction.

The core equation of TST, the Eyring equation, directly relates the rate constant to thermodynamic parameters of activation: [ k = \kappa \frac{kB T}{h} e^{-\Delta G^{\ddagger}/RT} ] where ( \kappa ) is the transmission coefficient (often approximated as 1), ( kB ) is Boltzmann's constant, ( h ) is Planck's constant, and ( \Delta G^{\ddagger} ) is the standard Gibbs free energy of activation [1]. This equation can be expanded to: [ k = \frac{kB T}{h} e^{\Delta S^{\ddagger}/R} e^{-\Delta H^{\ddagger}/RT} ] where ( \Delta S^{\ddagger} ) is the entropy of activation and ( \Delta H^{\ddagger} ) is the enthalpy of activation. In this framework, the entropic term ( \frac{kB T}{h} e^{\Delta S^{\ddagger}/R} ) provides a physical interpretation for the Arrhenius pre-exponential factor ( A ), while ( \Delta H^{\ddagger} ) relates closely to the empirical activation energy ( E_a ) [1] [21].

The reaction progress can be visualized on a potential energy surface. For a simple reaction, the path from reactants to products involves overcoming the activation energy barrier, ( Ea ), corresponding to the formation of the transition state. The adsorption energy of reactants onto a catalyst surface, a key parameter in heterogeneous catalysis, directly modifies this landscape by stabilizing the transition state and thus lowering ( Ea ), which dramatically increases the reaction rate [3].

[caption]Figure 1. Energy landscape for a chemical reaction[/caption]

The Critical Role of Adsorption in Catalysis

In surface-mediated reactions, the interaction between gas-phase molecules and the catalyst surface is described by adsorption and desorption processes. The strength of this interaction, quantified by the adsorption energy, is a primary descriptor for catalytic activity [23] [3]. Accurate prediction of adsorption energies on transition metal surfaces remains a significant challenge for computational methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT). Inaccuracies can lead to large errors in predicted activation barriers because the transition state often closely resembles the final chemisorbed state [3]. As shown in benchmark studies, even modern functionals like BEEF-vdW and RPBE can struggle to simultaneously describe both strong covalent bonds and weak dispersion interactions accurately, highlighting the need for advanced corrective schemes [3].

Experimental Determination of Activation Energy

A core experimental methodology for determining activation energy involves measuring reaction rates at different temperatures. The following section details a standard protocol for this determination.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Temperature-Dependent Kinetics

This procedure outlines the measurement of the activation energy for the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide catalyzed by the enzyme catalase, a model system for enzyme kinetics [20].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Glass Pressure Tube | Sealed reaction vessel to monitor gas evolution. |

| Teflon Threaded Plug | Seals the pressure tube; equipped with a rubber O-ring. |

| Gas Pressure Sensor | Measures the pressure of evolved O₂ gas in real-time. |

| Computer with Logger Pro | Interfaces with the gas pressure sensor for data collection. |

| Temperature-Controlled Water Bath | Maintains a constant temperature for each kinetic run. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) Stock | Reactant whose decomposition is studied (H₂O₂ → H₂O + ½O₂). |

| Phosphate Buffer | Maintains a constant pH for the enzymatic reaction. |

| Catalase Enzyme Stock | Biological catalyst that lowers the activation energy for H₂O₂ decomposition. |

| Magnetic Stir Plate & Stir Bar | Provides vigorous stirring to ensure rapid mixing and O₂ evolution. |

Step-by-Step Workflow [20]:

- Apparatus Setup: Assemble the reaction system as illustrated in Figure 2. The core component is a glass pressure tube seated in a temperature-controlled water bath. The tube is sealed with a Teflon plug connected via a luer lock to a gas pressure sensor.

- Temperature Equilibration: Heat the water bath to a target temperature between 5°C and 40°C (multiple temperatures, e.g., 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35°C, are required). Monitor the temperature with a thermometer and maintain it constant using ice or heat as needed.

- Reaction Initiation and Data Acquisition: For each trial, load the pressure tube with fixed volumes of stock H₂O₂ (e.g., 1.00 mL) and phosphate buffer (e.g., 23.00 mL). Start the Logger Pro data collection and then rapidly inject the stock enzyme solution (e.g., 1.00 mL) to initiate the reaction. Ensure the stir bar is set to a consistent, vigorous speed for all trials.

- Data Collection Replication: Perform at least seven independent kinetic runs, each at a different temperature within the specified range.

- Data Analysis: a. From the pressure vs. time data for each run, determine the initial rate of the reaction. b. Since the enzyme concentration is constant, the initial rate is proportional to the rate constant ( k ). Thus, ( k \propto \text{initial rate} ). c. Apply the linearized form of the Arrhenius equation: ( \ln k = \ln A - \frac{Ea}{R} \left( \frac{1}{T} \right) ). d. Plot ( \ln k ) (y-axis) against ( \frac{1}{T} ) in Kelvin (x-axis). The data should approximate a straight line. e. The slope of the best-fit line is ( -Ea/R ), from which the activation energy is calculated: ( E_a = -\text{slope} \times R ).

[caption]Figure 2. Experimental workflow for determining activation energy[/caption]

Advanced and High-Temperature Methodologies

Beyond conventional solution-phase chemistry, specialized techniques enable the study of reactions with extremely high activation barriers. Recent research demonstrates that high-temperature synthesis in solution (up to 500°C) can overcome formidable activation energies of 50–70 kcal mol⁻¹, which are unreachable under standard conditions. Using sealed capillaries and solvents like p-xylene, this method has achieved product yields up to 50% in minutes for reactions like the isomerization of N-substituted pyrazoles, bridging a significant gap in synthetic methodology [22].

In solid-state and materials chemistry, techniques like thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) are coupled with isoconversional methods such as the Kissinger–Akahira–Sunose (KAS) method to determine the apparent activation energy of complex processes like the hydrogen reduction of metal oxides during the fabrication of high-entropy alloys [24].

Contemporary Research and Data Presentation

Current research focuses on achieving a more accurate and balanced description of the energies governing surface reactions, particularly adsorption energies and activation barriers.

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Activation Energies in Diverse Systems

| Reaction/System | Experimental Method | Activation Energy (Ea) | Key Finding/Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isomerization of N-substituted pyrazoles [22] | High-temperature solution synthesis (up to 500°C) | 50 – 70 kcal mol⁻¹ | Demonstrates the accessibility of very high barriers under extreme but practical conditions. |

| Hydrogen reduction of Cr₂O₃ in CoCrFeNi HEA [24] | Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) & KAS method | Not explicitly stated (Apparent Ea determined) | Extended ball milling (30 h) reduced the temperature needed for reduction by ~115°C, enhancing feasibility. |

| Acetone adsorption/desorption on Ti₁₀O₂₀ clusters [8] | DFT with dispersion corrections & TST | Gibbs free energy of activation calculated | Theoretical framework links thermodynamic energies to sensor performance metrics (response/recovery time). |

Table 2: Performance of Computational Methods for Adsorption Energies on Transition Metal Surfaces [3]

| Computational Method/Functional | Type | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for Adsorption Energies | Notes on Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| BEEF-vdW | GGA (with dispersion) | > 2.7 kcal mol⁻¹ | Widely used; good for chemisorption but has room for improvement with physisorption. |

| RPBE | GGA | > 2.7 kcal mol⁻¹ | Tends to overestimate chemisorption energies. |

| RPBE + D3 | GGA (with dispersion) | ~2.7 kcal mol⁻¹ | Performance similar to BEEF-vdW when dispersion is applied selectively. |

| SW-R88 | Hybrid (RPBE + optB88-vdW) | < 2.7 kcal mol⁻¹ | Lower errors but lacks a specific functional form, complicating force calculations. |

| Cluster-Correction Scheme | PBC-DFT + higher-level QC | 2.2 kcal mol⁻¹ (Covalent), 2.7 kcal mol⁻¹ (Non-covalent), 1.1 kcal mol⁻¹ (Barriers) | Corrects periodic DFT with cluster calculations; offers a balanced and accurate description. |

A major frontier in the field is the development of more accurate computational methods. A 2022 study presented a cluster-correction scheme that combines periodic DFT calculations with higher-level quantum chemical calculations on small metal clusters. This approach significantly improves the accuracy of predicted adsorption energies and activation barriers, achieving a mean absolute error of just 1.1 kcal mol⁻¹ for activation barriers [3]. This precision is vital for the in silico design of new catalysts and materials, as it allows for reliable predictions of reaction energy paths.

The choice of theoretical model also critically impacts the interpretation of kinetic data. For instance, the pre-exponential factor ( A ) in desorption kinetics can vary by orders of magnitude depending on whether the adsorbate is modeled as a 2D ideal gas or a 2D ideal lattice gas, which in turn affects the derived desorption energy and lifetime [23]. This underscores the necessity of clearly stating the underlying model when reporting and comparing kinetic parameters.

The journey from reactants to products, governed by the principles of activation energy and reaction kinetics, is a cornerstone of chemical science. Mastery of these concepts, from the foundational Arrhenius and Transition State Theories to advanced experimental and computational methods, is indispensable for researchers aiming to develop new chemical processes, materials, and therapeutics. The ongoing refinement of techniques for measuring and predicting adsorption and activation energies, particularly through high-level computational corrections and high-temperature experimentation, continues to push the boundaries of accessible chemistry. A deep, quantitative understanding of the relationship between adsorption energy and transition state energy will remain a critical driver of innovation, enabling the rational design of catalytic systems and the synthesis of complex molecules across the pharmaceutical and materials science landscapes.

Energetic relationships, particularly those involving adsorption energies and transition state energies, serve as fundamental quantitative descriptors that bridge the gap between molecular-scale interactions and macroscopic functional outcomes in both catalysis and drug discovery. The principles of Transition State Theory (TST) provide a unified framework to understand and quantify the rates of chemical reactions, whether for a molecule binding to a catalyst surface or a drug ligand binding to a protein target. [1] [23] In catalysis, the interaction strength between an adsorbate and a catalyst surface, quantified by the adsorption energy, directly influences the activation barrier and thus the reaction rate. [25] Similarly, in pharmaceutical research, the binding free energy between a drug candidate and its biological target determines the drug's potency and efficacy. [26] [27] This technical guide explores the profound practical implications of these energetic relationships, detailing how their measurement, calculation, and manipulation are revolutionizing the design of efficient catalysts and potent therapeutics. We place this discussion within the broader context of adsorption and transition state energy relationship research, highlighting the convergent methodologies used across these seemingly distinct fields to control and optimize molecular interactions.

Theoretical Foundations: Transition State Theory and Free Energy Relationships

Core Principles of Transition State Theory

Transition State Theory (TST) explains the reaction rates of elementary chemical reactions by positing a quasi-equilibrium between reactants and an activated transition state complex. [1] The theory provides a direct connection between the thermodynamics of this activated complex and the kinetic rate constant. The central equation derived from TST is the Eyring equation:

[ k = \frac{k_B T}{h} \exp\left(-\frac{\Delta G^\ddagger}{RT}\right) ]

where (k) is the reaction rate constant, (k_B) is Boltzmann's constant, (h) is Planck's constant, (T) is temperature, (R) is the gas constant, and (\Delta G^\ddagger) is the standard Gibbs free energy of activation. [1] This free energy of activation can be decomposed into enthalpic ((\Delta H^\ddagger)) and entropic ((\Delta S^\ddagger)) components:

[ \Delta G^\ddagger = \Delta H^\ddagger - T\Delta S^\ddagger ]

The pre-exponential factor (\frac{k_B T}{h}) in the Eyring equation represents the frequency at which the activated complex converts to products, typically on the order of (10^{12}) to (10^{13}) s⁻¹ at room temperature. [1] For surface processes like adsorption and desorption, the precise form of the pre-exponential factor depends critically on the model chosen for the adsorbed state (e.g., 2D ideal gas vs. 2D ideal lattice gas), which can lead to variations of several orders of magnitude in calculated rates and derived energies. [23]

Linear Free Energy Relationships (LFERs) and Their Applications

Linear Free Energy Relationships (LFERs) are powerful tools that correlate changes in reaction free energies ((\Delta G)) with changes in activation free energies ((\Delta \Delta G^\ddagger)). These relationships emerge from the Bell-Evans-Polanyi principle and the Brensted equation, which formally connect thermodynamics to kinetics. [28] In practical terms, LFERs enable researchers to predict reaction rates or binding affinities based on simpler-to-measure equilibrium properties or molecular descriptors.

A prominent example comes from enzymology, where the electronic properties of the reduced flavin mononucleotide (FMN) coenzyme in isopentenyl diphosphate:dimethylallyl diphosphate isomerase (IDI-2) demonstrated a clear LFER. [29] As shown in Table 1, modifications to the flavin structure systematically altered both the steady-state kinetic parameters and the observed kinetic isotope effects, revealing that the flavin N5 atom serves as a general base catalyst in the isomerization reaction. [29]

Table 1: LFERs in IDI-2 Catalysis with Modified Flavin Cofactors

| Flavin Analogue | (\mathbf{\Sigma\sigma}) | (\mathbf{k_{cat}}) (s⁻¹) | (\mathbf{k{cat}/Km}) (µM⁻¹s⁻¹) | D(\mathbf{k_{cat}}) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7,8-Cl₂-FMN | 0.94 | 0.11 | 0.033 | 2.8 |

| 7-Cl-FMN | 0.37 | 0.029 | 0.018 | 2.2 |

| FMN (native) | 0.00 | 0.47 | 0.11 | 1.9 |

| 8-Me-FMN | -0.17 | 1.1 | 0.21 | 1.6 |

| 7-Me-FMN | -0.17 | 2.2 | 0.43 | 1.6 |

Modern applications of LFERs extend beyond mechanistic analysis to direct catalyst and drug design. Multivariate LFERs that use computationally determined descriptors of ligands or catalysts can predict experimental outcomes such as reaction rate, selectivity, or binding affinity, providing both predictive power and chemical insight into the underlying interactions governing the observed trends. [28]

Energetic Relationships in Heterogeneous Catalysis

Adsorption Energies and Catalytic Activity

In heterogeneous catalysis, the binding strength of reactants, intermediates, and products to the catalyst surface fundamentally determines the overall catalytic activity and selectivity. This relationship is formally described by the Sabatier principle, which posits that an optimal catalyst should bind reactants strongly enough to facilitate the reaction but weakly enough to allow products to desorb. Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations of adsorption energies provide invaluable data for analyzing these chemical transformations. [25]

The immense practical impact of accurately determining adsorption energies is illustrated by the challenge of modeling methanol decomposition on transition metal surfaces. As shown in Table 2, different DFT functionals yield dramatically different adsorption energies for various reaction steps, with no single functional providing accurate estimates across all intermediates. [25] This highlights the critical need for improved computational strategies that reliably describe both strong covalent and weak dispersion interactions on transition metal surfaces.

Table 2: Challenges in Calculating Methanol Decomposition Energies (kcal mol⁻¹) on Pd(111) and Ni(111) [25]

| Surface | Species | Experimental Value | PBE | optB86b-vdW | PBE+D3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pd(111) | CH₃OH | -10.7 | -4.1 | -10.6 | -10.4 |

| Pd(111) | CH₃O | -62.5 | -59.6 | -69.2 | -68.8 |

| Pd(111) | CO | -40.0 | -33.1 | -46.1 | -47.3 |

| Ni(111) | CH₃OH | -10.3 | -3.7 | -10.4 | -10.2 |

| Ni(111) | CH₃O | -66.5 | -65.4 | -74.0 | -73.6 |

| Ni(111) | CO | -32.0 | -26.6 | -38.4 | -39.2 |

Advanced Computational Approaches

To address the limitations of standard DFT functionals, researchers have developed hybrid approaches that combine periodic DFT calculations with higher-level quantum chemical techniques on small cluster models. [25] This method applies a correction from higher-level calculations on small metal clusters to improve periodic band structure adsorption energies and barriers. When benchmarked against 38 reliable experimental covalent and non-covalent adsorption energies and five activation barriers, this approach achieved mean absolute errors of 2.2 kcal mol⁻¹, 2.7 kcal mol⁻¹, and 1.1 kcal mol⁻¹, respectively—lower than widely used functionals like BEEF-vdW and RPBE. [25]

Another application involves using TST to analyze the adsorption and desorption of small molecules like acetone on metal oxide clusters. Ti₁₀O₂₀ clusters have been used with DFT-D calculations to determine Gibbs free energies of adsorption and activation, enabling the calculation of sensor response and recovery times as functions of temperature and acetone concentration. [8] The temperature of maximum response was calculated to be 356°C, providing practical design parameters for acetone sensing applications. [8]

Energetic Relationships in Drug-Target Binding

Binding Free Energy as a Central Determinant of Drug Efficacy

In pharmaceutical research, the binding free energy ((\Delta G)) between a drug candidate and its biological target directly determines therapeutic potency. Accurate prediction of this value has been described as the "holy grail" of computational drug discovery, as it would dramatically reduce the cost and time of drug development. [27] The binding free energy can be decomposed into various components:

[ \Delta G = \Delta E{MM} + \Delta G{solv} - T\Delta S ]

where (\Delta E{MM}) represents the gas-phase molecular mechanics energy, (\Delta G{solv}) is the solvation free energy change, and (T\Delta S) accounts for entropic contributions. [26]

Recent advances have demonstrated the power of combining quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) with free energy calculation methods. In one comprehensive study, researchers developed four protocols that combine QM/MM calculations with the mining minima (M2) method, testing them on 9 targets and 203 ligands. [27] The best-performing protocol achieved a Pearson's correlation coefficient of 0.81 with experimental binding free energies and a mean absolute error of 0.60 kcal mol⁻¹, surpassing many existing methods and achieving accuracy comparable to popular relative binding free energy techniques but at significantly lower computational cost. [27]

The Critical Role of Electronic Polarization

Traditional molecular mechanics force fields often fail to adequately capture electronic polarization effects—the redistribution of electron density when a ligand binds to a protein. This limitation can be addressed by incorporating QM/MM methodologies, where the ligand is treated quantum mechanically while the protein environment is handled with molecular mechanics. [26] [27]

The importance of electronic effects is highlighted in the QM/MM-PB/SA (Poisson-Boltzmann/Surface Area) method, which introduces a QM/MM interaction energy term accounting for ligand polarization upon binding. [26] Studies comparing semi-empirical methods (DFTB-SCC, PM3, MNDO, etc.) found that implementation of a DFTB-SCC semi-empirical Hamiltonian derived from Density Functional Theory provided superior results, confirming the importance of accurate electronic contributions in binding free energy calculations. [26]

Diagram 1: QM/MM Mining Minima Workflow for Binding Free Energy Prediction

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Protocol: Adsorption Energy Correction Using Cluster Models

This protocol improves the accuracy of adsorption energy calculations for transition metal surfaces by combining periodic DFT with higher-level cluster calculations. [25]

Materials and Computational Methods:

- Periodic DFT Code: Software such as VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, or CASTEP for bulk surface calculations.

- Wavefunction-Based Code: Software such as MOLPRO, ORCA, or TURBOMOLE for high-level cluster calculations.

- Cluster Generation: Creation of small metal clusters representing the local binding site.

Procedure:

- Periodic Calculation: Perform a standard DFT calculation of the adsorption energy ((E_{ads}^{DFT, periodic})) using an appropriate exchange-correlation functional.

- Cluster Model Calculation:

- Construct a cluster model (e.g., M₁₀-M₂₀ atoms) representing the local adsorption site.

- Calculate the adsorption energy ((E{ads}^{DFT, cluster})) at the same DFT level.

- Recalculate the adsorption energy ((E{ads}^{high, cluster})) using a higher-level method (e.g., CCSD(T), DLPNO-CCSD(T)) on the same cluster.

- Correction Application:

- Compute the energy correction: (\Delta E{corr} = E{ads}^{high, cluster} - E{ads}^{DFT, cluster})

- Apply to the periodic result: (E{ads}^{corrected} = E{ads}^{DFT, periodic} + \Delta E{corr})

- Validation: Benchmark against reliable experimental data or higher-level calculations.

Protocol: QM/MM-Mining Minima for Binding Free Energy Estimation

This protocol enhances binding free energy predictions by incorporating QM-derived charges into a conformational sampling framework. [27]

Materials and Computational Methods:

- Software: VeraChem VM2 software, AMBER or GROMACS for MD simulations, Gaussian or ORCA for QM calculations.

- System Preparation: Protein and ligand structures in appropriate file formats (PDB, MOL2).

Procedure:

- Initial Conformational Sampling: Perform classical mining minima (MM-VM2) calculation to identify probable conformers and their weights.

- Conformer Selection: Select either the most probable conformer or multiple conformers representing a significant probability mass (e.g., >80%).

- QM/MM Charge Derivation:

- For each selected conformer, set up a QM/MM calculation with the ligand in the QM region and the protein in the MM region.

- Calculate the electrostatic potential (ESP) and derive restrained ESP (RESP) charges for the ligand atoms.

- Charge Replacement and Free Energy Calculation: Replace the force field atomic charges in the selected conformers with the newly derived ESP charges.

- Final Free Energy Processing: Perform free energy processing (FEPr) on the charge-corrected conformers to obtain the final binding free energy estimate.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Energetic Relationship Studies

| Reagent/Software | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO | Periodic DFT calculations | Adsorption energy on surfaces |

| ORCA, Gaussian | Wavefunction-based QM calculations | High-level cluster corrections |

| AMBER, GROMACS | Molecular dynamics simulations | Protein-ligand binding |

| VeraChem VM2 | Mining minima calculations | Conformational sampling for binding free energy |

| BEEF-vdW, RPBE | Exchange-correlation functionals | DFT for surface science |

| CCSD(T), DLPNO-CCSD(T) | High-level electron correlation methods | Benchmark quality cluster calculations |

| PLUMED | Enhanced sampling plugin for MD | Free energy calculations |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of energetic relationship research is rapidly evolving, with several emerging trends poised to significantly impact both catalysis and drug discovery:

AI-Powered Trial Simulations: Quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) models and "virtual patient" platforms are now simulating thousands of individual disease trajectories, allowing researchers to test dosing regimens and refine inclusion criteria before a single patient is dosed. AI-powered digital twins are transforming clinical development, with companies like Unlearn.ai validating digital twin-based control arms in Alzheimer's trials that can reduce placebo group sizes considerably. [30]

Advanced Protein Degradation Modalities: PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs) represent a novel therapeutic paradigm that leverages energetic relationships differently from traditional inhibitors. These small molecules drive protein degradation by bringing together the target protein with an E3 ligase. Over 80 PROTAC drugs are currently in development pipelines, with research expanding beyond the four most commonly used E3 ligases to include new targets like DCAF16, DCAF15, DCAF11, KEAP1, and FEM1B. [30]

Multivariate LFERs for Rational Design: The application of multivariate LFERs using purely computational data is gaining traction for both catalyst design and drug optimization. These approaches isolate features of complex chemical systems, achieving both quantitative prediction of interaction energetics and clear interpretability, providing chemical insight into the underlying interactions that influence observed trends. [28]

Diagram 2: Interdisciplinary Connections in Energetic Relationship Research

Energetic relationships, particularly those involving adsorption energies and transition state energies, serve as fundamental design parameters that transcend the traditional boundaries between heterogeneous catalysis and pharmaceutical research. The unified framework provided by Transition State Theory enables researchers in both fields to connect molecular-level interactions to functional outcomes, whether reaction rates or binding affinities. Advanced computational methodologies—from cluster-corrected DFT for surface science to QM/MM mining minima for drug binding—are progressively enhancing our ability to accurately predict and optimize these energetic relationships. As emerging trends in AI, multivariate LFERs, and novel therapeutic modalities continue to evolve, the strategic manipulation of energetic relationships will undoubtedly remain central to the rational design of next-generation catalysts and therapeutics. The convergent approaches across these disciplines highlight the power of physical organic chemistry principles to address diverse challenges in molecular design and optimization.

Computational Strategies: From DFT to Machine Learning for Energy Profiling

Density Functional Theory (DFT) represents a computational quantum mechanical modelling method widely employed in physics, chemistry, and materials science to investigate the electronic structure of many-body systems, particularly atoms, molecules, and condensed phases [31]. For researchers studying adsorption processes and reaction barriers, DFT serves as an indispensable tool that enables the prediction of material behavior from first principles without requiring empirical parameters. The fundamental premise of DFT lies in using functionals of the spatially dependent electron density to determine system properties [31]. This approach transforms the intractable many-body problem of interacting electrons into a tractable single-body problem through the Kohn-Sham equations, making complex surface interactions computationally feasible [31].

In the context of adsorption energy and transition state calculations, DFT provides atomic-level insights that are often challenging to obtain experimentally. The theory's versatility allows researchers to model the interaction between adsorbates and substrate surfaces, quantify the strength of these interactions through adsorption energies, and identify the transition states that dictate reaction pathways and rates. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical guide to applying DFT for adsorption and barrier calculations, framed within ongoing research into the relationship between adsorption energy and transition state energy.

Theoretical Foundations

Fundamental DFT Principles

The theoretical foundation of DFT rests on two seminal theorems proved by Hohenberg and Kohn. The first theorem demonstrates that the ground-state properties of a many-electron system are uniquely determined by an electron density that depends on only three spatial coordinates [31]. This revolutionary insight reduces the many-body problem of N electrons with 3N spatial coordinates to just three spatial coordinates, significantly simplifying computational complexity. The second HK theorem defines an energy functional for the system and proves that the ground-state electron density minimizes this energy functional [31].

The Kohn-Sham equations, developed later, form the practical basis for most modern DFT calculations [31]:

[\hat{H}^{\text{KS}} \psii = \left[ -\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2 + V{\text{eff}}(\mathbf{r}) \right] \psii = \epsiloni \psi_i]