Advanced Catalyst Design for Biomass Gasification and Tar Reforming: Recent Breakthroughs and Future Pathways

This comprehensive review synthesizes cutting-edge advancements in catalyst design for efficient and sustainable biomass gasification and tar reforming, tailored for researchers and scientists in energy technology and chemical engineering.

Advanced Catalyst Design for Biomass Gasification and Tar Reforming: Recent Breakthroughs and Future Pathways

Abstract

This comprehensive review synthesizes cutting-edge advancements in catalyst design for efficient and sustainable biomass gasification and tar reforming, tailored for researchers and scientists in energy technology and chemical engineering. We explore the fundamental mechanisms of tar formation and catalytic reforming, detailing the development and performance of novel catalytic systems including transition bimetallic, carbon-based, and waste-derived catalysts. The article provides a deep dive into sophisticated strategies for catalyst structure optimization, anti-deactivation mechanisms, and regeneration protocols. Further, it critically evaluates methodological applications through process modeling, techno-economic analysis, and sustainability assessments, offering a validated comparison of catalytic performance to guide the development of robust, cost-effective, and environmentally benign next-generation catalysts for carbon-neutral energy systems.

The Catalyst Frontier: Unraveling Tar Formation and Fundamental Reforming Mechanisms

Tar formation presents a major technical challenge that impedes the widespread commercialization of biomass gasification technologies. Tars are complex, condensable hydrocarbons whose deposition can lead to equipment blockage, catalyst deactivation, and systemic operational failures. Within the broader context of catalyst design for biomass gasification and tar reforming research, understanding tar composition, behavior, and mitigation strategies is fundamental. This application note provides a structured overview of tar characteristics, classifications, and impacts, supplemented with experimental protocols for tar analysis and catalyst evaluation to support researchers in developing effective tar management solutions. The persistent issue of tar formation affects both the economic viability and technical reliability of gasification systems, necessitating continued research into advanced catalytic solutions.

Tar Composition and Classification

Chemical Composition

Biomass tar constitutes a complex mixture of organic compounds resulting from the incomplete decomposition of biomass during the gasification process. Its composition varies significantly depending on feedstock and operational conditions but primarily includes polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), phenols, aldehydes, and other oxygenated species [1]. The molecular complexity of tar stems from the differential thermal degradation of biomass components: cellulose and hemicellulose produce lighter tar compounds, while the complex aromatic structure of lignin yields heavier, more recalcitrant polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons that are particularly challenging to remove [2]. Tars also contain heteroatoms including sulfur, chlorine, and fuel-bound nitrogen, alongside alkali metals that contribute to their corrosive potential [3].

Table 1: Major Chemical Constituents of Biomass Tar

| Compound Class | Representative Species | Characteristics | Relative Reactivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aromatics | Toluene, Benzene, Naphthalene | Single to multi-ring structures | Variable; lighter aromatics more reactive |

| Phenolic Compounds | Phenol, Cresols, 4-methoxy-2-methylphenol | Oxygen-containing, water-soluble | Moderate |

| Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) | Anthracene, Pyrene | Multi-ring, high molecular weight | Low, highly stable |

| Heterocyclic Compounds | Pyridine | Contain nitrogen, sulfur, or oxygen | Variable |

Classification Systems

Several classification systems have been established to categorize tars based on different physicochemical properties. The International Energy Agency (IEA) Bioenergy definition categorizes tars as "hydrocarbons of higher molecular weight than benzene" [3]. A more functional classification system, as outlined in Table 2, categorizes tars based on their chemical behavior and condensability:

Table 2: Tar Classification Based on Condensability and Properties

| Tar Category | Description | Key Properties | Impact on Operations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Tars | Products of initial pyrolysis; highly oxygenated | High reactivity, lower condensation temperature | Less problematic due to reactivity |

| Secondary Tars | Products of conversion at intermediate temperatures | Stable phenolic compounds, olefins | Moderate operational impact |

| Tertiary Tars | Products of conversion at high temperatures (>800°C) | Highly stable PAHs, low reactivity | Severe operational issues; difficult to remove |

Another critical property is the tar dew point, defined as the temperature at which tar partial pressure equals its saturation vapor pressure, initiating condensation. Heavier polyaromatic hydrocarbons significantly elevate the dew point, increasing the risk of condensation in downstream equipment at higher temperatures [3]. The specific application of the syngas dictates the required tar cleanliness levels: for internal combustion engines, tar content must be below 100 mg/Nm³, while gas turbines require less than 5 mg/Nm³, and fuel cells or methanol production demand even stricter levels below 1 mg/Nm³ [3].

Operational Impacts of Tar in Gasification Systems

Tar accumulation in gasification systems manifests multiple detrimental effects that compromise efficiency, reliability, and economic viability. The most immediate impact is mechanical fouling through pipeline blockage and filter clogging, which restricts gas flow and increases pressure drops [2] [3]. This fouling necessitates frequent maintenance shutdowns and chemical cleaning, driving up operational costs.

Tars also induce corrosion of downstream equipment, particularly when condensed tars combine with moisture to form aggressive electrochemical environments that attack metal surfaces [3]. Furthermore, the presence of tars leads to catalyst deactivation in downstream processes such as syngas cleaning and biofuel synthesis. Tar compounds physically block active sites and undergo coking reactions that deposit solid carbon, effectively poisoning catalysts designed for reforming, water-gas shift, or synthesis reactions [4] [3].

The reduction in gasification efficiency represents another significant impact, as the carbon and hydrogen bound in tar molecules represent chemical energy that fails to contribute to the useful syngas energy content [3]. This energy loss directly diminishes the cold gas efficiency of the process. Additionally, tar condensation creates environmental and health concerns through the formation of phenolic species that contaminate process water, requiring expensive treatment while posing potential health risks [3].

Experimental Protocols for Tar Analysis and Catalyst Evaluation

Tar Sampling and Characterization Workflow

A standardized protocol for tar analysis ensures reproducible results across different research groups. The following workflow outlines key procedural steps:

Protocol 1: Tar Sampling and Quantification

System Stabilization: Ensure the gasification system operates at steady-state conditions (stable temperature, pressure, and flow rates) for at least 30 minutes before sampling.

Isokinetic Sampling: Draw a representative gas sample through a heated probe and particulate filter maintained at 350°C to prevent tar condensation. Use an impinger train containing dichloromethane (DCM) or acetone cooled in an ice bath.

Solvent Extraction: Combine the contents of all impingers and rinse with additional solvent to ensure complete transfer of tar compounds. Filter if necessary to remove any particulate matter.

Sample Concentration: Carefully evaporate the solvent using a rotary evaporator at controlled temperature (≤40°C) to avoid loss of volatile tar components. Transfer the concentrated tar to a pre-weighed vial and complete solvent removal under a gentle nitrogen stream.

Gravimetric Analysis: Weigh the vial to determine total tar content. Calculate concentration in mg/Nm³ based on the sampled gas volume.

GC-MS Characterization: Dissolve a portion of the tar in appropriate solvent for gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis to determine individual tar components. Use a DB-5 or equivalent column with temperature programming from 40°C to 300°C.

Catalyst Activity Testing for Tar Reforming

Evaluating catalyst performance for tar reforming requires standardized testing protocols. The following methodology employs model tar compounds to ensure reproducibility:

Protocol 2: Catalyst Performance Evaluation for Tar Reforming

Catalyst Preparation:

- Support Selection: Use γ-Al₂O₃ with high surface area (>150 m²/g) as support material [1] [3].

- Active Metal Loading: Employ wet impregnation with aqueous solutions of Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O and Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O to achieve target metal loading (typically 5-15 wt% Ni with varying Ni/Fe ratios) [1].

- Calcination: Dry at 110°C for 2 hours followed by calcination at 500-700°C for 4 hours in air atmosphere.

Catalyst Characterization:

- Textural Properties: Determine surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution using N₂ physisorption (BET method).

- Crystalline Structure: Identify crystalline phases using X-ray diffraction (XRD).

- Acid-Base Properties: Characterize using temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) of NH₃ and CO₂.

Catalytic Activity Testing:

- Reactor System: Use a fixed-bed or fluidized-bed reactor system capable of operating at 600-900°C [3].

- Model Tar Compound: Select appropriate model compounds (toluene for aromatics, 4-methoxy-2-methylphenol for phenolic tars) dissolved in water or delivered via syringe pump [1] [3].

- Reaction Conditions: Maintain gas hourly space velocity (GHSV) of 5,000-20,000 h⁻¹, with steam-to-carbon ratio of 1-3 and CO₂ concentration of 5-20% when evaluating CO₂ reforming [1].

- Product Analysis: Use online gas chromatography (GC) with TCD and FID detectors to quantify permanent gases (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄) and residual tar compounds.

Performance Metrics Calculation:

- Tar Conversion (%) = [(Ctar,in - Ctar,out)/C_tar,in] × 100

- Gas Yield (mol/g_tar) = moles of product gas component per gram of tar converted

- H₂/CO Ratio = molar ratio of hydrogen to carbon monoxide in product gas

- Carbon Balance = (carbon in products)/(carbon in feed) × 100

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Tar Reforming Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specifications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nickel Nitrate Hexahydrate | Precursor for active metal in catalysts | Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, ≥98.5% purity; primary source of Ni for reforming catalysts |

| Iron Nitrate Nonahydrate | Promoter for bimetallic catalyst systems | Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O, ≥98% purity; enhances carbon resistance and redox properties |

| γ-Alumina Support | High-surface-area catalyst support | Surface area >150 m²/g, pore volume >0.4 mL/g; provides mechanical stability |

| Toluene | Model tar compound for experimental studies | Analytical standard, ≥99.9%; represents aromatic fraction of biomass tar |

| 4-methoxy-2-methylphenol | Model compound for oxygenated tars | Surrogate for lignin-derived tars; contains methoxy and hydroxyl functional groups |

| Dichloromethane | Solvent for tar sampling and extraction | HPLC grade, ≥99.9%; effective for dissolving diverse tar compounds |

| Ceria Promoter | Catalyst promoter for oxygen storage | CeO₂, enhances redox properties and catalyst stability |

| Dielectric Barrier Discharge Reactor | Plasma-assisted catalytic reforming | Non-thermal plasma source; enables low-temperature tar reforming [1] |

Addressing the tar challenge in gasification systems requires comprehensive understanding of tar composition, classification, and operational impacts. This application note has outlined standardized protocols for tar analysis and catalyst evaluation to support reproducible research in this critical area. The development of advanced catalytic materials, particularly bimetallic systems such as Ni-Fe alloys supported on modified alumina, shows significant promise for efficient tar reforming while mitigating catalyst deactivation. Future research directions should focus on enhancing catalyst durability under real gasification conditions, integrating plasma-catalytic processes for low-temperature operation, and developing multifunctional materials that combine tar reforming with in-situ CO₂ capture. Such advances will contribute substantially to the realization of efficient, economically viable, and sustainable biomass gasification systems aligned with global carbon reduction goals.

Application Note: Fundamental Principles and Current Research Landscape

Biomass gasification represents a pivotal renewable energy technology for sustainable fuel and chemical production, yet its efficiency is critically hampered by the formation of tar, a complex mixture of condensable hydrocarbons [3] [5]. Tar causes severe operational issues including pipeline blockage, equipment corrosion, and catalyst deactivation, ultimately reducing process efficiency and syngas quality [3]. Catalytic tar reforming has emerged as the most effective hot-gas cleaning strategy, converting problematic tars into valuable syngas (H₂ and CO) through steam reforming, CO₂ reforming (dry reforming), and catalytic cracking pathways [6] [1] [3]. This application note details the core principles, experimental protocols, and reagent solutions essential for researcher implementation, framed within advanced catalyst design for biomass gasification research.

Tar Composition and Classification

Biomass tar composition varies significantly based on feedstock and gasification conditions, but primarily contains aromatic hydrocarbons, phenolic compounds, and heterocyclic species [3]. Tar is typically classified based on molecular structure and condensability, as shown in Table 1. For research purposes, model compounds like toluene, benzene, naphthalene, and 4-methoxy-2-methylphenol (4M2MP) are employed to simulate the complex reactions of actual biomass tar in controlled environments [1] [3].

Table 1: Classification and Properties of Biomass Tar

| Class | Representative Compounds | Key Characteristics | Research Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary & Secondary | Phenols, Cresols, Xylene [3] | Mixed functional groups (OH, CH₃, OCH₃) [3] | Good surrogates for lignin-derived tars; 4M2MP is a common model compound [3] |

| Tertiary (Alkyl-PAHs) | Methyl-naphthalene [3] | Light Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) [3] | -- |

| Tertiary (Heterocyclic) | Pyridine, Quinoline [3] | Contain nitrogen or oxygen atoms [3] | -- |

| Tertiary (Condensed PAHs) | Pyrene, Anthracene [3] | Heavy, multi-ring aromatics with high dew points [3] | Major contributors to equipment fouling and clogging [3] |

Application Note: Core Reforming Pathways and Catalyst Systems

Steam Reforming (CSR)

Catalytic Steam Reforming (CSR) is a well-established, thermodynamically efficient process for hydrogen production from biomass-derived tars and bio-oil [6]. The fundamental steam reforming reaction for a generic tar molecule (CₙHₘOₖ) is highly endothermic:

CₙHₘOₖ + (n-k)H₂O → nCO + (n + m/2 - k)H₂ [6]

The produced CO can further react with steam via the exothermic Water-Gas Shift (WGS) reaction to maximize H₂ yield:

CO + H₂O CO₂ + H₂ [6]

The overall combined reaction becomes:

CₙHₘOₖ + (2n-k)H₂O → nCO₂ + (2n + m/2 - k)H₂ [6]

CSR requires high temperatures (700–1100 °C), high steam-to-carbon (S/C) ratios (5-20), and metal-based catalysts (typically nickel) to achieve high conversion efficiencies [6]. A major challenge is coke formation through decomposition or the Boudouard reaction, which deactivates catalysts [6].

CO₂ Reforming (Dry Reforming)

CO₂ reforming utilizes CO₂ as an oxidant to convert tar into syngas, offering a pathway for CO₂ valorization and reducing the carbon footprint of the gasification process [1]. The general reaction is:

CₙHₘOₖ + nCO₂ → (x/2)H₂ + 2nCO [1]

This approach is advantageous as it consumes CO₂, often available from renewable or waste streams, and produces syngas with a lower H₂/CO ratio, suitable for specific synthesis processes [1]. When coupled with innovative technologies like Non-Thermal Plasma (NTP), CO₂ reforming can achieve high tar conversion at significantly lower temperatures (e.g., 250 °C) than conventional thermal processes [1].

Catalytic Cracking

Catalytic cracking involves the thermal decomposition of large tar molecules into smaller, non-condensable gases like H₂, CH₄, CO, and CO₂ in the presence of a catalyst, without the addition of steam or CO₂ [6] [3]. The reaction can be simplified as:

pCₙHₓ (tar) → qCₘHᵧ (smaller tar) + rH₂ [6]

This pathway is often accompanied by undesirable carbon formation reactions (CₙHₓ → nC + (x/2)H₂), which lead to catalyst deactivation [6].

Table 2: Operational Parameters for Different Tar Reforming Pathways

| Parameter | Steam Reforming (CSR) | CO₂ Reforming | Catalytic Cracking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Temperature | 700–1100 °C [6] | 250 °C (Plasma-Catalytic) to 700-900 °C (Thermal) [1] | 550–800 °C [6] |

| Key Reagent | Steam (H₂O) | Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) | -- |

| Molar Ratio (Reagent/C) | S/C = 5–20 [6] | CO₂/C₇H₈ = ~1.5 (for toluene) [1] | -- |

| Primary Products | H₂, CO (with subsequent CO₂ from WGS) [6] | CO, H₂ [1] | H₂, CH₄, CO, CO₂, and smaller hydrocarbons [6] [3] |

| Main Challenge | Coke formation, high energy demand [6] | Catalyst coking and sintering [1] | Coke formation, leading to deactivation [6] |

Catalyst Systems for Tar Reforming

Catalyst design is paramount for efficient tar conversion and resistance to deactivation. Performance hinges on the synergy between active metals, supports, and promoters [7] [5].

- Active Metals: Ni-based catalysts are widely used due to their high activity and cost-effectiveness [6] [1]. To mitigate deactivation, bimetallic systems like Ni-Fe, Ni-Co, and Ru-Ni are developed, which enhance carbon resistance and H₂ selectivity [1] [5].

- Supports: The support material (e.g., γ-Al₂O₃, CeO₂, SBA-15) provides high surface area, stabilizes metal particles, and influences reactivity via strong metal-support interactions (SMSI) [1] [3] [5].

- Promoters: Additives like CeO₂ or La₂O₃ increase oxygen mobility on the catalyst surface, facilitating the gasification of carbon deposits and improving stability [3] [5].

Protocol: Experimental Methodology for Plasma-Enhanced Catalytic CO₂ Reforming of Tar

This protocol details the methodology for plasma-enhanced CO₂ reforming of toluene, a model tar compound, using bimetallic Nix-Fey/Al₂O₃ catalysts, based on recent research [1].

Catalyst Synthesis: Incipient Wetness Impregnation

- Objective: To prepare bimetallic Ni-Fe catalysts with varying molar ratios (e.g., 3:1, 2:1, 1:1, 1:2, 1:3) supported on γ-Al₂O₃.

- Materials:

- Support: γ-Al₂O₃

- Metal Precursors: Nickel nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O), Iron nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O)

- Solvent: Deionized water

- Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Calculate the required masses of metal precursors to achieve the target Ni/Fe molar ratios and total metal loading. Dissolve the precursors in deionized water, using a volume of water approximately equal to the pore volume of the γ-Al₂O₃ support.

- Impregnation: Slowly add the aqueous solution dropwise to the γ-Al₂O₃ support while stirring continuously to ensure uniform distribution.

- Aging: Allow the impregnated material to age at room temperature for 12 hours.

- Drying: Dry the sample in an oven at 105 °C for 6 hours.

- Calcination: Calcine the dried material in a muffle furnace at 500 °C for 5 hours in static air to decompose the nitrates and form the metal oxides.

Catalyst Characterization

- X-Ray Diffraction (XRD): Analyze the crystalline phases of the calcined catalysts. Identify characteristic peaks for γ-Al₂O₃, NiO, Fe₂O₃, and any mixed phases like NiAl₂O₄ [1].

- N₂ Physisorption: Determine the surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution using BET and BJH methods. Expect type IV isotherms with H3 hysteresis loops, confirming mesoporous structures [1].

- Additional Techniques (Optional): Temperature-Programmed Reduction (TPR) to assess reducibility, and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) to determine surface composition.

Plasma-Catalytic Activity Test

- Objective: To evaluate the performance of Nix-Fey/Al₂O₃ catalysts in a Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) non-thermal plasma reactor for toluene reforming.

- Reactor Setup: A coaxial DBD reactor consisting of a high-voltage electrode, a ground electrode, and a quartz dielectric barrier. The catalyst is packed in the discharge zone.

- Experimental Conditions:

- Reaction Temperature: 250 °C (maintained by an external furnace)

- Pressure: Ambient

- Discharge Power: 20–60 W (variable frequency or voltage)

- Feed Composition: Toluene (C₇H₈), CO₂, and balance gas (e.g., N₂ or Ar). A typical CO₂/C₇H₈ molar ratio is 1.5 [1].

- Gas Hourly Space Velocity (GHSV): Maintain a constant flow rate.

- Procedure:

- Catalyst Pre-treatment: Reduce the catalyst in situ under a H₂/Ar stream at 500 °C for 2 hours before reaction.

- Plasma Activation: Initiate the DBD plasma at the desired discharge power.

- Product Analysis: Analyze the effluent gas using online Gas Chromatography (GC) equipped with a TCD and FID to quantify permanent gases (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄) and any residual hydrocarbons.

- Performance Metrics: Calculate toluene conversion, H₂ selectivity, CO selectivity, and syngas (H₂+CO) yield.

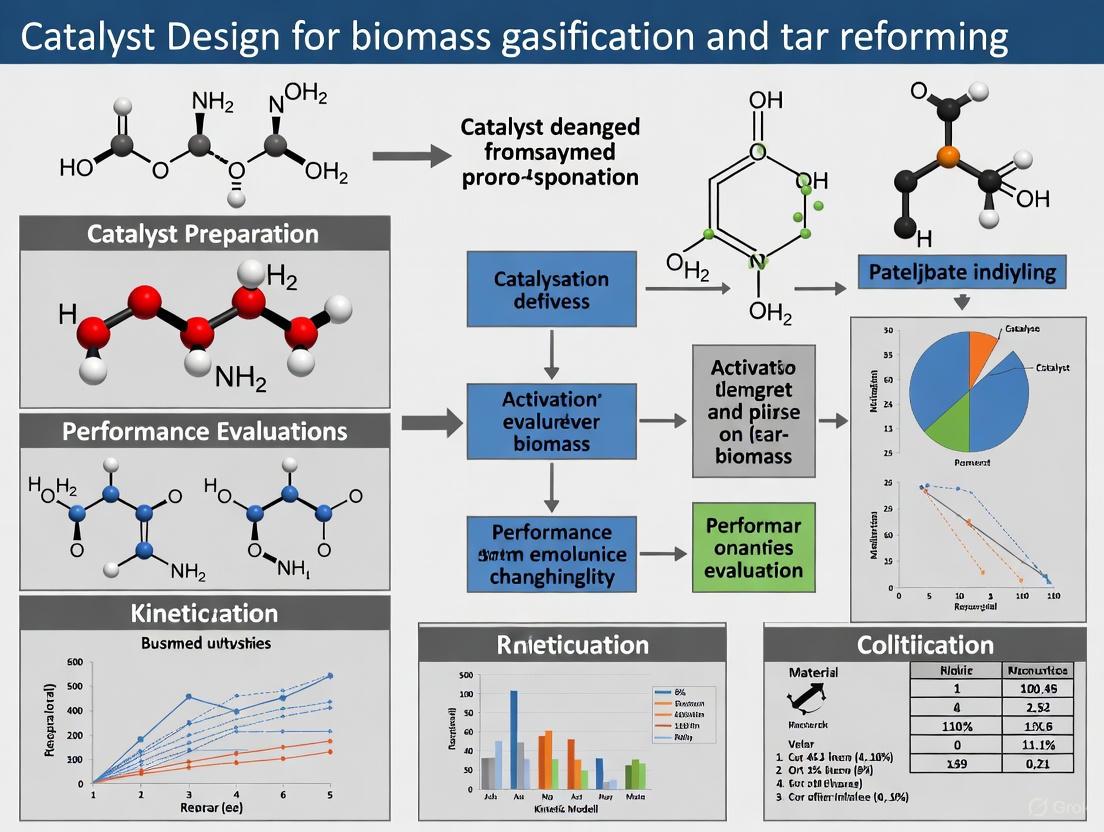

Diagram 1: Plasma-Catalytic Reforming Experimental Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key steps for evaluating catalysts in plasma-enhanced CO₂ reforming, from preparation to performance analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Tar Reforming Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nickel Nitrate (Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) | Active metal precursor for catalyst synthesis [1] | High-purity grade; forms NiO upon calcination, reducible to metallic Ni [1] |

| Iron Nitrate (Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O) | Co-metal precursor for bimetallic catalysts [1] | Used with Ni to form Ni-Fe alloys; enhances carbon resistance [1] |

| γ-Alumina (γ-Al₂O₃) | Catalyst support [1] [3] | Provides high surface area and mesoporous structure; interacts strongly with Ni [1] |

| Ceria (CeO₂) | Catalyst promoter or support [3] | Enhances oxygen storage and transfer, gasifying carbon deposits and improving stability [3] [5] |

| Toluene (C₇H₈) | Model tar compound [1] | Represents alkylated aromatic hydrocarbons in real tar; common for standardized testing [1] |

| 4-Methoxy-2-methylphenol | Model tar compound [3] | Surrogate for lignin-derived, oxygen-containing tars; contains key functional groups (OH, OCH₃) [3] |

| Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) Reactor | Non-thermal plasma source [1] | Generates reactive species (electrons, ions, radicals) to activate reactions at low bulk temperatures [1] |

Diagram 2: Core Pathways and Components of Catalytic Tar Reforming. This diagram illustrates the interaction between tar, reforming agents, and catalyst components, leading to syngas production while highlighting the universal challenge of coke formation.

In the thermochemical conversion of biomass via gasification, the formation of tar represents a significant challenge, causing operational issues and reducing process efficiency. Catalytic reforming has emerged as a promising solution for tar elimination and conversion into valuable syngas (H₂ and CO). Within this domain, active metal systems based on nickel (Ni), cobalt (Co), and iron (Fe) play a pivotal role, primarily through their unique abilities to activate C-C and C-H bonds, which are the foundational chemical linkages in stable tar molecules. This application note details the roles, performance, and practical application of these metals within the broader context of advanced catalyst design for biomass gasification and tar reforming, providing researchers with structured data and reproducible protocols.

Performance Comparison of Active Metal Systems

The catalytic performance of Ni, Co, and Fe is governed by their intrinsic properties and their interactions within catalyst formulations. The table below summarizes their distinct roles and quantitative performance in tar reforming.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Ni, Co, and Fe in Tar Reforming Catalysis

| Metal | Primary Role in Bond Activation | Key Catalytic Features | Reported Performance Highlights | Common Deactivation Issues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nickel (Ni) | High activity for C-C, C-H, C-O, and O-H bond activation; facilitates hydrogenation reactions. [8] | High activity-to-cost ratio; forms effective alloys (e.g., with Fe). [1] [9] | Toluene conversion of 98.11% over Ni-Fe/CaO. [8] Ni₃-Fe₁/Al₂O3 showed highest H₂/CO selectivity in plasma-catalytic reforming. [1] | Susceptible to coke deposition and metal sintering. [1] [9] |

| Iron (Fe) | Strong activity for C-C bond activation; provides redox capacity. [8] | Enhances carbon resistance; migrates to remove carbon deposits; cost-effective. [1] [8] | Fe/CaO-Ca₁₂Al₁₄O₃₃ showed a 58.5% increase in 1-methylnaphthalene conversion vs. CaO alone. [8] | |

| Cobalt (Co) | Similar reforming activity to Ni; often used in bimetallic systems. | Used in bi-metallic Ni-Co systems to enhance stability and resistance to coke. [9] | Ni-Co/Mg(Al)O catalysts achieve complete tar elimination under tested conditions, though with eventual coke deactivation. [9] | Deactivation by coke formation, with morphology dependent on conditions. [9] |

| Ni-Fe Bimetallic | Synergistic effect; Ni activates C-H bonds, while Fe handles C-C cleavage and carbon removal. | Strong basicity of Ni₃-Fe₁/Al₂O₃ enhances CO₂ adsorption and carbon resistance. [1] | DFT studies show Ni-Fe/CaO can reduce the energy barrier of toluene cracking by 61.3%. [8] | Enhanced resistance to carbon deposition compared to monometallic Ni. [1] [8] |

| Ni-Co Bimetallic | Aims to combine high activity of Ni with improved stability from Co. | Hydrotalcite-derived Ni-Co/Mg(Al)O systems are targeted for low-cost, high-performance alloys. [9] | Performance is sensitive to operating parameters (temperature, S/C ratio, tar composition). [9] | High-molecular-weight tar enhances formation of metal-encapsulating coke. [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Catalyst Evaluation

Protocol: Plasma-Enhanced Catalytic CO₂ Reforming of Tar using Nix-Fey/Al₂O3 Catalysts

This protocol outlines the experimental procedure for evaluating bimetallic Ni-Fe catalysts in a dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) non-thermal plasma reactor, adapted from foundational research [1].

- Primary Objective: To investigate the performance of Nix-Fey/Al₂O₃ catalysts in the CO₂ reforming of toluene (a common tar model compound) for syngas production.

- Materials & Reagents:

- Catalysts: Nix-Fey/Al₂O₃ catalysts with varying Ni/Fe molar ratios (e.g., 3:1, 2:1, 1:1, 1:2, 1:3), synthesized via wet impregnation.

- Reactants: Toluene (≥99.9%, tar model compound), CO₂ (≥99.995%).

- Equipment: DBD non-thermal plasma reactor, syringe pump, gas chromatograph (GC), mass flow controllers.

- Procedure:

- Catalyst Preparation: Synthesize catalysts by depositing Ni and Fe nitrates on a γ-Al₂O₃ support. Dry at 110°C for 12 hours and calcine in air at a specified temperature (e.g., 500-700°C) for 4 hours.

- Reactor Setup: Load the catalyst (e.g., 0.5 g) into the DBD plasma reactor. Dilute the catalyst bed with an inert material like α-Al₂O₃ to manage the reaction exothermicity.

- Reaction Conditions:

- Temperature: 250°C (maintained by an external oven).

- Pressure: Ambient.

- Discharge Power: Vary between 20-100 W to assess its effect.

- Feed Composition: Adjust the CO₂/C₇H₈ molar ratio (e.g., 1.5 is found optimal [1]) and the total gas flow rate to achieve desired space velocity.

- Product Analysis: Direct the reactor effluent to an online GC equipped with a TCD and FID for quantification of permanent gases (H₂, CO, CO₂) and any residual hydrocarbons.

- Key Measurements: Calculate toluene conversion, and H₂ and CO selectivity as a function of time on stream (TOS) for different catalyst compositions and operating parameters.

Protocol: Steam Reforming of Tar with Ni-Co/Mg(Al)O Catalysts

This protocol details the testing of hydrotalcite-derived bimetallic catalysts for tar steam reforming under conditions simulating biomass gasification syngas [9].

- Primary Objective: To study the stability and coke formation of Ni-Co/Mg(Al)O catalysts during steam reforming of various tar model compounds.

- Materials & Reagents:

- Catalysts: Ni-Co/Mg(Al)O (e.g., 20-20 wt% Ni-Co ratio) with hydrotalcite-like precursors prepared by co-precipitation [9].

- Reactants: Model tar compounds (toluene, 1-methylnaphthalene, phenol), model syngas (10/35/25/25/5 mol% CH₄/H₂/CO/CO₂/N₂).

- Equipment: Fixed-bed tubular reactor, syringe pump, online GC, temperature-programmed oxidation with mass spectrometry (TPO-MS), Raman spectrometer.

- Procedure:

- Catalyst Pre-treatment: Reduce the catalyst in situ in 50 mol% H₂ in Ar (200 NmL/min) for 16 hours at 670°C.

- Reaction Conditions:

- Temperature: Test a range from 650°C to 800°C.

- Pressure: Atmospheric.

- Steam-to-Carbon (S/C) Ratio: Vary between 2.0 and 5.0.

- Tar Loading: Test different concentrations (e.g., 10, 20, 30 g/Nm³).

- Gas Hourly Space Velocity (GHSV): Keep constant (e.g., 85,000 NmL/gₐₜmin).

- Stability Test: Run experiments for an extended period (e.g., 8 hours TOS) while monitoring product composition.

- Post-Reaction Analysis (Coke Characterization):

- TPO-MS: Heat spent catalyst samples from 35°C to 900°C in dilute O₂; monitor CO₂ emission to quantify and profile coke.

- Raman Spectroscopy: Analyze the structure of carbon deposits (e.g., D and G bands to distinguish disordered and graphitic carbon).

- STEM: Examine the morphology and location of coke (e.g., filamentous vs. encapsulating).

- Key Measurements: Determine tar conversion, syngas composition, and catalyst deactivation rate. Classify coke types based on TPO-MS and microscopy results.

Computational & Advanced Analysis Protocols

Protocol: DFT Investigation of Tar Catalytic Cracking Mechanisms

Density Functional Theory (DFT) simulations provide atomic-level insight into the interaction between tar molecules and catalyst surfaces, guiding rational catalyst design [8].

- Primary Objective: To investigate the adsorption properties and initial cracking mechanisms of tar model compounds (benzene, toluene, phenol) on pure and transition metal-doped CaO surfaces.

- Computational Methods:

- Software: Use modules like DMol³ within materials studio suites, with spin polarization for magnetic atoms (Ni, Fe).

- Model Setup:

- Build a CaO (100) surface slab from its bulk face-centered cubic structure.

- Create doped surfaces by substituting a Ca atom with a Ni or Fe atom (e.g., Ni-CaO, Fe-CaO).

- Calculations:

- Adsorption Energy: Calculate the energy of tar molecule adsorption on the catalyst surface.

- Reaction Pathway: Locate transition states and calculate activation energy barriers for key bond-breaking steps (e.g., first C-H scission in toluene).

- Electronic Analysis: Compute properties like Partial Density of States (PDOS), bond order population, and Electron Density Difference (EDD) to understand electronic interactions.

- Key Outputs: Adsorption energies and configurations, energy profiles for reaction pathways, and electronic structure data linking catalyst electronic properties to activity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Tar Reforming Catalyst Research

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tar Model Compounds | Represents specific tar components for controlled experiments. | Toluene, 1-Methylnaphthalene, Phenol. These represent mono-aromatics, polyaromatics, and oxygenated tars, respectively. [9] [8] |

| Catalyst Support | Provides high surface area, stabilizes metal particles, and can participate in catalysis. | γ-Al₂O₃, Mg(Al)O, CeO₂, CaO. Al₂O₃ is common; Mg(Al)O from hydrotalcites enhances dispersion; CeO₂ confers redox properties; CaO captures CO₂. [1] [9] [8] |

| Metal Precursors | Source of active metals for catalyst synthesis. | Nitrate Salts (e.g., Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O). Commonly used due to solubility and decomposition properties. [9] |

| Non-Thermal Plasma Reactor | Generates reactive species (electrons, ions, radicals) to activate stable molecules at low temperatures. | Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) Reactor. Used in plasma-catalysis to enhance tar reforming at mild conditions. [1] |

| Coke Characterization Suite | Identifies and quantifies carbon deposits on spent catalysts. | TPO-MS, Raman Spectroscopy, STEM. TPO-MS quantifies coke; Raman identifies graphitic character; STEM visualizes coke morphology. [9] |

Visualization of Pathways and Catalyst Dynamics

Diagram 1: Generalized Workflow of Catalytic Tar Reforming

Diagram 2: Valence-Restrictive MSI Influencing Reaction Pathway

The strategic application of Ni, Co, and Fe, both individually and in bimetallic formulations, is central to designing effective catalysts for biomass tar reforming. Ni excels in C-H bond activation, Fe in C-C bond cleavage and carbon resistance, and Co acts as a stabilizing partner in alloys. The integration of experimental techniques with computational modeling provides a powerful framework for understanding reaction mechanisms and deactivation processes. Future research should focus on optimizing metal-support interactions, exploring the dynamic structural evolution of metal sites under operating conditions [10], and developing robust, multi-functional catalysts that can withstand the complex environment of real biomass gasification gases.

Application Notes: The Role of Supports and Promoters in Tar Reforming Catalysts

Performance Metrics of Promoted Catalysts in Tar Reforming

The strategic application of catalyst supports and promoters significantly enhances catalytic performance in biomass tar reforming by improving metal dispersion, stability, and synergistic effects. The table below summarizes quantitative performance data for various supported and promoted catalysts documented in recent research.

Table 1: Performance of supported and promoted catalysts in tar model compound reforming.

| Catalyst Formulation | Reaction | Temperature (°C) | Conversion / Yield | Key Performance Feature | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 wt.% Ni/5CeO₂-Cr₂O₃ | CO₂ Methanation | 350 | 73.3% CO₂ conversion | Superior activity due to enhanced basicity & Ni dispersion | [11] |

| 10 wt.% La-15 wt.% Ni/Biochar | Toluene Steam Reforming | 400 | 93% conversion, 87% H₂ yield | High basicity & oxygen vacancies enhance low-temperature activity | [12] [13] |

| Ni₃-Fe₁/Al₂O₃ | Plasma-catalytic CO₂ Reforming of Toluene | 250 | High syngas selectivity | Strong basicity and high CO₂ adsorption capacity | [1] |

| 2.4-NiAl-7 (Ordered Mesoporous) | Toluene Steam Reforming | 750 | 99.9% conversion, 181.2 mmol H₂/g | Excellent stability for 30 h; high carbon deposition resistance | [14] |

Functional Mechanisms of Supports and Promoters

- Support Functions: High-surface-area supports like γ-Al₂O₃ and biochar provide a porous structure for high metal dispersion, prevent sintering of active sites, and facilitate reactant access [1] [14]. Biochar supports offer additional advantages including rich surface functional groups, tunable porosity, and cost-effectiveness [13] [5].

- Promoter Effects: Rare earth metal oxides (CeO₂, La₂O₃, Y₂O₃) act as structural and electronic promoters.

- CeO₂ enhances catalytic performance for CO₂ methanation by improving redox properties and increasing surface basicity for CO₂ adsorption [11].

- La₂O₃ doping in Ni/Biochar catalysts creates strong metal-support interaction, increases surface basicity (up to 2.95 mmol/g), and generates abundant oxygen vacancies (84.1%), which promote H₂O adsorption and dissociation, thereby facilitating coke removal and significantly boosting low-temperature toluene reforming activity and stability [12] [13].

- Synergistic Bimetallic Effects: In Ni-Fe/Al₂O₃ catalysts, Fe introduction increases lattice oxygen content and provides redox capacity for effective carbon deposit removal via migration of iron oxide. The Ni₃-Fe₁/Al₂O₃ formulation demonstrates optimal synergy for syngas production [1].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: One-Pot Solid-State Synthesis of Ni/MₓOᵧ-Cr₂O₃ Catalysts

This protocol outlines the synthesis of promoted Ni/Cr₂O₃ catalysts for CO₂ methanation, adapted from [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Metal Precursors: Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O (Merck, 98%), Cr(NO₃)₃·9H₂O (Merck, 98%), and promoter nitrates (e.g., Ce(NO₃)₃·6H₂O, Merck, 99%).

- Precipitating Agent: (NH₄)₂CO₃ (Merck, 95.3%).

- Equipment: Mortar and pestle, muffle furnace, tube furnace.

Procedure

- Grinding: Combine salt precursors of Ni, Cr, and the chosen promoter (e.g., Ce, La, Y) with a stoichiometric amount of (NH₄)₂CO₃ in a mortar.

- Reaction: Grind the mixture continuously for 20 minutes. The combination will become moist and pasty, indicating the reaction has initiated.

- Drying: Dry the resulting paste at 120°C for 12 hours.

- Calcination: Calcine the dried solid in a muffle furnace at 400°C for 4 hours.

- Reduction: Prior to catalytic testing, reduce the catalyst in a tube furnace under a hydrogen flow (40 mL/min) at 800°C for 3 hours.

Protocol 2: Wetness Impregnation of La-Promoted Ni/Biochar Catalyst

This protocol details the preparation of biochar-supported catalysts for low-temperature steam reforming of tar, as described in [12] [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Support: Wood chip biochar produced from a gasifier.

- Active Metal Precursor: Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O.

- Promoter Precursor: La(NO₃)₃·6H₂O.

- Equipment: Rotary evaporator, drying oven, muffle furnace.

Procedure

- Support Preparation: Sieve the raw biochar to the desired particle size (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mm).

- Impregnation Solution: Prepare an aqueous solution containing stoichiometric concentrations of Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O and La(NO₃)₃·6H₂O to achieve the target metal loadings (e.g., 15 wt.% Ni and 10 wt.% La).

- Incipient Wetness Impregnation: Slowly add the aqueous solution to the biochar support under continuous stirring until the incipient wetness point is reached.

- Aging: Allow the impregnated catalyst to age at room temperature for 12 hours.

- Drying: Dry the catalyst in an oven at 105°C for 12 hours.

- Calcination: Calcine the dried catalyst in a muffle furnace at a temperature of 500°C for 5 hours under a static air atmosphere.

Protocol 3: Synthesis of Ordered Mesoporous Ni-Al₂O₃ via EISA

This protocol describes the Evaporation-Induced Self-Assembly (EISA) method for creating catalysts with enhanced metal-support interaction and superior stability, based on [14].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Metal Precursors: Aluminum isopropoxide (Al(OiPr)₃, 98%), Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O (99%).

- Structure-Directing Agent: Triblock copolymer Pluronic P123 ((PEO)₂₀(PPO)₇₀(PEO)₂₀).

- Solvent & Catalyst: Anhydrous ethanol (99.5%), nitric acid (HNO₃, 68-70 wt%).

- Equipment: Closed container, muffle furnace.

Procedure

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve 2.0 g of Pluronic P123 in 40 mL of anhydrous ethanol. Then, add 4.08 g of Al(OiPr)₃ and a specified amount of Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O (for 10 wt.% Ni loading).

- Acid Hydrolysis: Add a controlled molar ratio of HNO₃ to Al(OiPr)₃ (e.g., H/Al = 0.07) to the solution under vigorous stirring.

- Gelation and Aging: Continue stirring for 5 hours until a homogeneous solution forms. Transfer the solution to a closed container and allow it to undergo gelation and age at 40°C for 48 hours.

- Drying: Dry the resulting gel at 100°C for 24 hours.

- Calcination: Remove the template and crystallize the material by calcining in a muffle furnace. The temperature and duration should be optimized (e.g., 600-700°C for 4 hours).

Visualization of Catalyst Design Principles

Catalyst Design Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for the rational design of supported and promoted catalysts, from synthesis to performance optimization.

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for the design of supported and promoted catalysts, highlighting key decisions in support and promoter selection.

Structure-Activity Relationships

This diagram maps the critical catalyst properties engineered by supports and promoters to the resulting performance enhancements in tar reforming.

Diagram 2: Structure-activity relationships linking engineered catalyst properties to performance outcomes in tar reforming.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key research reagents and their functions in catalyst synthesis for tar reforming.

| Reagent/Material | Example Function in Catalyst Synthesis | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Pluronic P123 | Structure-directing agent for creating ordered mesoporous supports via EISA. | Synthesis of Ni-Al₂O₃ with controlled pore size and strong metal-support interaction [14]. |

| Biochar (Wood Chip) | Catalyst support providing high surface area, porosity, and surface functional groups for metal dispersion. | Support for Ni and La-Ni catalysts in low-temperature steam reforming of toluene [12] [13]. |

| Rare Earth Nitrates | Precursors for promoters (Ce, La) that enhance basicity, oxygen vacancy concentration, and metal dispersion. | La-doping to boost activity and stability of Ni/Biochar catalysts [12] [13]. |

| Nickel Nitrate Hexahydrate | Common precursor for the active Ni metal phase, responsible for C-C/C-H bond cleavage. | Primary active metal in most reforming catalysts discussed [11] [13] [1]. |

| Iron Nitrate Nonahydrate | Precursor for a secondary metal to form bimetallic systems, enhancing carbon resistance. | Creation of Ni-Fe alloys in Al₂O₃-supported catalysts for plasma-catalytic CO₂ reforming [1]. |

| Ammonium Carbonate | Precipitating agent in solid-state synthesis for catalyst preparation. | Used in one-pot mechanochemical synthesis of Ni/MₓOᵧ-Cr₂O₃ catalysts [11]. |

The thermochemical conversion of biomass and solid waste through gasification is a cornerstone technology for producing renewable syngas (H₂ and CO). A significant challenge impeding its commercialization is the formation of tar, a complex mixture of condensable hydrocarbons, which can block and deactivate downstream systems [7] [15]. Catalytic tar reforming has emerged as the most efficient strategy to convert these undesirable tars into additional syngas, thereby enhancing both yield and process efficiency [7] [16]. The performance of this process is intrinsically linked to the design of the catalyst. This article details the application and experimental protocols for three emerging material platforms—biochar, mineral catalysts, and waste-derived systems—which are pivotal for advancing catalyst design in biomass gasification and tar reforming research.

The selection of a catalyst platform involves trade-offs between activity, cost, stability, and ease of fabrication. The table below provides a comparative analysis of the three emerging platforms.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Emerging Catalyst Platforms for Tar Reforming

| Platform | Key Active Components | Primary Advantages | Major Challenges | Representative Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biochar-based | • Transition Metals (Fe, Ni)• Persistent Free Radicals (PFRs)• Inherent Alkali & Alkaline Earth Metals | • Inexpensive & renewable feedstock [17]• Tunable surface functionality & porosity [18]• Can act as catalyst & catalyst support [17] [18]• Potential for self-healing properties [7] | • Variable composition based on feedstock & pyrolysis conditions [17]• Susceptibility to attrition & combustion [19]• Deactivation from coking & ash deposition [7] | • Effective in activating peroxymonosulfate for contaminant degradation [17]• High surface area (up to 3263 m²/g after activation) [18] |

| Mineral Catalysts | • Natural Olivines & Dolomites• Synthetic Ni-based & Noble Metals (Pt, Ru)• Mixed Metal Oxides | • High catalytic activity (esp. Ni & noble metals) [16]• Dolomites are low-cost and widely available [16]• Good thermal stability | • Noble metals are expensive [16]• Ni-based catalysts prone to coking & sulfur poisoning [16] |

• Ni-based catalysts are highly effective for steam reforming [16]• Steam reforming process efficiency: 74–85% [16] |

| Waste-Derived Systems | • Ash from Biomass/MSW• Red Mud (Bauxite Residue)• Fe-rich Industrial Slags | • Ultralow-cost or negative-cost feedstock [15]• Promotes waste valorization & circular economy [19]• Often contains inherent catalytic metals (e.g., Fe, Ca) [15] | • Highly variable & complex composition [15]• Limited long-term stability data• May require pre-treatment to enhance activity/durability | • Social, Technological, Economic, Environmental, and Political (STEEP) analysis supports sustainability [16] |

Application Notes for Emerging Platforms

Biochar-based Catalysts

Biochar is a carbon-rich porous solid produced from the pyrolysis of biomass, serving as both a catalyst and an excellent catalyst support [17] [18]. Its catalytic activity stems from its surface functional groups, persistent free radicals (PFRs), and the presence of inherent or impregnated inorganic species [17]. In tar reforming, biochar facilitates cracking and reforming reactions. The PFRs on its surface can generate reactive oxygen species (e.g., •OH) that participate in tar degradation [17]. When loaded with transition metals like Ni or Fe, the catalytic performance is significantly enhanced through a synergistic effect where biochar provides a high-surface-area, reducing environment that minimizes coke deposition on the active metal sites [7] [19].

Key application areas include:

- In-situ Tar Reforming: Biochar can be directly used within a gasifier or in a secondary reformer bed to convert tars, simplifying the reactor design [7].

- Peroxymonosulfate (PMS) Activation: In environmental remediation, biochar composites are highly effective in activating PMS to generate sulfate radicals (SO₄•⁻) for degrading organic contaminants in water and soil, a mechanism analogous to tar breakdown [17]. Biochar's adsorption properties concentrate pollutants near active sites, enhancing degradation efficiency [17].

Mineral Catalysts

This platform encompasses both natural minerals and synthetically engineered inorganic catalysts.

- Natural Catalysts (Dolomite, Olivine): These are primarily non-metallic catalysts (Ca/Mg-based) used for primary tar cracking due to their low cost. They are often employed in-bed to reduce tar yields but are less effective for complete tar reforming to syngas and suffer from poor mechanical strength [16] [15].

- Synthetic Metal Catalysts: Ni-based catalysts are the most widely studied and effective for steam reforming due to their high activity for C-C bond cleavage [16]. However, they are prone to deactivation by sintering and coking. Strategies to mitigate this include using appropriate supports (e.g., Al₂O₃, ZrO₂) and promoters (e.g., MgO, K) to improve dispersion and stability [7] [16]. Noble metals (Pt, Ru) offer superior activity and coke resistance but are cost-prohibitive for large-scale applications [16].

Waste-Derived Systems

This platform focuses on leveraging industrial by-products and waste materials as catalytic precursors, aligning with circular economy principles [19]. Examples include:

- Ash from Biomass or Municipal Solid Waste (MSW): This material often contains catalytic oxides (K₂O, CaO, MgO) that can catalyze tar cracking [15].

- Red Mud: A residue from alumina production, rich in Fe₂O₃, which can act as an active component for reforming [15]. These waste-derived materials typically require pre-treatment, such as calcination, to remove volatile content and stabilize the active phases. Their main advantage is ultra-low cost, but their heterogeneous nature requires rigorous quality control for consistent performance [19] [15].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Preparation of a Ni/Biochar Catalyst for Steam Tar Reforming

This protocol describes the synthesis of a nickel-impregnated biochar catalyst for application in steam reforming of biomass-derived tar.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Ni/Biochar Catalyst Synthesis

| Item | Specification / Function |

|---|---|

| Biomass Feedstock | Wood chips, agricultural residue (e.g., rice husk, straw). Precursor for biochar. |

| Nickel Nitrate Hexahydrate (Ni(NO₃)₂•6H₂O) | ≥98.5% purity. Source of active nickel metal. |

| Tube Furnace | Capable of reaching 900°C with programmable temperature ramp and inert gas (N₂) flow. |

| Muffle Furnace | For calcination in air atmosphere. |

| Rotary Evaporator | For efficient solvent removal during impregnation. |

| Deionized Water | Solvent for impregnation solution. |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Biochar Production via Slow Pyrolysis:

- Feedstock biomass is dried at 105°C for 24 hours and ground to a particle size of 0.5-1.0 mm.

- Load 50 g of the ground biomass into a quartz boat and place it in the tube furnace.

- Purge the system with nitrogen (N₂) at a flow rate of 200 mL/min for 30 minutes to ensure an oxygen-free environment.

- Pyrolyze the biomass by heating the furnace to 500°C at a rate of 10°C/min and maintain this temperature for 60 minutes under continuous N₂ flow [17] [18].

- After holding, allow the system to cool to room temperature under N₂. Collect the resulting biochar and note the yield.

Wet Impregnation with Nickel:

- Prepare a 1M aqueous solution of Ni(NO₃)₂•6H₂O.

- Add the biochar to the nickel solution using a volume sufficient to achieve the desired nickel loading (e.g., 5-15 wt.%). Ensure the biochar is fully submerged.

- Stir the mixture for 4 hours at room temperature.

- Remove the water using a rotary evaporator at 60°C to ensure uniform distribution of the nickel precursor within the biochar pores.

- Dry the impregnated material overnight in an oven at 105°C.

Catalyst Activation (Calcination & Reduction):

- Calcination: Place the dried catalyst in a muffle furnace and heat to 400°C in air for 2 hours to decompose the nickel nitrate to nickel oxide (NiO).

- Reduction (In-situ or Ex-situ): The NiO/Biochar is typically reduced in-situ within the reformer. This involves heating the catalyst to 600-800°C under a flow of H₂ or H₂/N₂ mixture (e.g., 20% H₂ in N₂) for 1-2 hours to reduce NiO to metallic Ni (Ni⁰), the active phase for reforming.

Protocol: Activity Testing for Tar Reforming in a Fixed-Bed Reactor

This protocol outlines a standard procedure for evaluating the performance of a prepared catalyst in tar reforming.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Catalytic Activity Testing

| Item | Specification / Function |

|---|---|

| Fixed-Bed Reactor System | Quartz or stainless-steel tube reactor, furnace, temperature controller, gas feeding system. |

| Tar Model Compound | Toluene, naphthalene, or phenol. Represents key components of real tar. |

| Syringe Pump | For precise delivery of liquid tar model compound and water. |

| Online Gas Chromatograph (GC) | Equipped with TCD and FID detectors for quantifying H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄, and light hydrocarbons. |

| Gas Mass Flow Controllers | For precise control of carrier gas (N₂) and other gaseous feeds. |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Catalyst Loading and System Check:

- Load 1.0 g of the catalyst (sized to 250-500 μm) into the center of the fixed-bed reactor, supported by quartz wool.

- Pressurize the system with N₂ and perform a leak check. Set the N₂ flow to the desired space velocity (e.g., 5000 h⁻¹ GHSV).

In-situ Catalyst Reduction:

- Heat the reactor to the reduction temperature (e.g., 600°C) under N₂ flow.

- Switch the gas flow to a reducing gas (e.g., 20% H₂ in N₂) for 1-2 hours to activate the catalyst.

Tar Reforming Reaction:

- After reduction, adjust the reactor temperature to the desired reforming temperature (e.g., 700-900°C).

- Use a syringe pump to inject a mixture of the tar model compound (e.g., toluene) and water (steam) into the pre-heating zone of the reactor. A typical steam-to-carbon (S/C) molar ratio is 3.5 [16].

- Allow the system to stabilize for at least 30 minutes.

Product Analysis and Data Collection:

- Connect the reactor outlet to the online GC.

- Collect gas product samples at regular intervals (e.g., every 30 minutes) for at least 3 hours to monitor catalyst stability.

- Analyze the composition of the product gas (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄).

Performance Calculation:

- Tar Conversion (%): Calculated based on the carbon balance from the tar feed and unreacted tar/hydrocarbons in the product.

- Hydrogen Yield (%): (Moles of H₂ produced) / (Theoretical maximum moles of H₂ from complete reforming) × 100%.

- Gas Selectivity (%): Selectivity towards H₂ or CO is calculated from the dry gas composition, excluding N₂.

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate the catalyst development workflow and the relationship between catalyst properties and performance.

Diagram 1: Catalyst development workflow.

Diagram 2: Catalyst properties and performance relationships.

Designing Next-Generation Catalysts: Synthesis, Characterization, and Process Integration

Application Notes

Bimetallic catalysts are pivotal in advancing the efficiency of biomass gasification and tar reforming processes, primarily by enhancing syngas production and mitigating catalyst deactivation. The strategic combination of metals, such as Ni-Fe and Ni-Co, creates synergistic effects that improve catalytic activity, stability, and resistance to carbon deposition, which is a common challenge in tar reforming reactions [20] [4].

Ni-Fe Bimetallic Catalysts demonstrate exceptional performance in tar cracking and reforming. Supported on materials like MgO–Al2O3 and La0.8Ca0.2CrO3/MgO–Al2O3, they achieve high hydrogen yields and exhibit significant resistance to carbon formation at temperatures around 700°C [21]. The addition of Fe to Ni catalysts enhances oxygen species coverage and provides redox properties, which facilitate the removal of carbon deposits [1] [22]. Furthermore, in plasma-enhanced CO2 reforming of toluene, Ni-Fe/Al2O3 catalysts with a Ni/Fe molar ratio of 3:1 show superior CO and H2 selectivity, leveraging strong CO2 adsorption capacity to reduce carbon buildup [1].

Ni-Co Bimetallic Catalysts, particularly when supported on hydrotalcite-derived Mg(Al)O, are highly effective for steam reforming of tar impurities. These catalysts achieve complete tar elimination across a range of operating conditions (650–800°C) [9]. The Ni-Co synergy enhances catalyst stability, although operational parameters must be optimized to minimize deactivation from coke formation. Characterization of spent catalysts reveals various carbon morphologies, underscoring the importance of managing coke formation to maintain long-term activity [9].

Ru-Ni Alloys, while not explicitly detailed in the provided search results, are recognized in the broader literature for their high activity and stability in reforming reactions. Their inclusion here is based on their established potential in catalytic biomass processing, warranting further investigation within this specific application context.

Table 1: Performance Summary of Bimetallic Catalysts in Tar Reforming

| Catalyst System | Optimal Support | Key Reaction Conditions | Tar Conversion/Performance | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni-Fe | MgO-Al2O3, La0.8Ca0.2CrO3/MgO-Al2O3 [21] | 700°C, Steam or CO2 co-feed [21] | High H2 yield, >90% biomass conversion to gases [21] [22] | Excellent resistance to carbon deposition [21] [1] |

| Ni-Fe | SBA-15 [22] | 600°C, Steam reforming [22] | ~90% biomass conversion to gases [22] | High metal dispersion, strong metal-support interaction [22] |

| Ni-Fe | Al2O3 (Plasma-catalytic) [1] | 250°C, CO2 reforming [1] | High toluene conversion & syngas selectivity [1] | Effective at low temperatures, high CO2 adsorption [1] |

| Ni-Co | Mg(Al)O [9] | 650-800°C, S/C = 2-5 [9] | Complete tar elimination [9] | High activity-to-cost ratio, effective tar removal [9] [4] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Data from Key Studies

| Catalyst | Reaction | Temperature | Conversion/ Yield | Carbon Deposition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni-Fe/MgO-Al2O3 [21] | Naphthalene Cracking | 700 °C | ~95% initial conversion | Low, further reduced with H₂O/CO₂ co-feed |

| 6Ni-1Fe/SBA-15 [22] | Steam Reforming of Biomass Tar | 600 °C | ~90% biomass conversion | Lower than monometallic Ni catalyst |

| Ni3-Fe1/Al2O3 [1] | Plasma-catalytic CO₂ Reforming of Toluene | 250 °C | High syngas selectivity | High resistance due to strong basicity |

| Ni-Co/Mg(Al)O [9] | Steam Reforming of Tar | 750 °C | Complete tar elimination | Coke formation dependent on T and S/C ratio |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Highly Dispersed Ni-Fe/SBA-15 Catalysts via Oleic-Acid Assisted Impregnation

This protocol describes the synthesis of highly dispersed bimetallic Ni-Fe nanoparticles on mesoporous SBA-15 silica, achieving high activity and stability in steam reforming of biomass tar [22].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Support Material: Mesoporous silica SBA-15.

- Metal Precursors: Nickel nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O), Iron(III) nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O).

- Dispersing Agent: Oleic acid (OA).

- Template: Triblock copolymer P123.

- Silica Source: Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS).

- Solvents: Deionized water, Hydrochloric acid (HCl, 2.0 M).

Procedure:

- Synthesis of SBA-15 Support: a. Dissolve 4.0 g of P123 in 30 mL of deionized water. b. Add 120 mL of 2.0 M HCl solution to the mixture while maintaining temperature between 35–40°C. c. Introduce 8.5 g of TEOS under constant stirring for 20 hours. d. Transfer the solution to a polypropylene bottle and hydrothermally treat it at 90°C for 48 hours in a static oven. e. Recover the solid product via vacuum filtration, wash thoroughly with deionized water, and dry overnight at 60°C. f. Calcinate the dried material at 550°C for 8 hours in air to obtain the final SBA-15 support [22].

Incipient Wetness Impregnation: a. Prepare an aqueous solution of Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O and Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O to achieve the target metal loading (e.g., 6 wt% Ni and 1 wt% Fe). b. Mix the metal precursor solution with a small, specified amount of oleic acid. c. Impregnate the SBA-15 support with the mixed metal-OA solution dropwise until incipient wetness is achieved. d. Dry the impregnated catalyst overnight at 60°C. e. Calcinate the catalyst in air at a specified temperature (e.g., 550°C) to decompose the nitrates and OA, forming the active metal oxides [22].

Catalyst Reduction: a. Prior to the reaction, reduce the calcined catalyst in a flow of hydrogen (e.g., 50% H₂ in Ar) at a elevated temperature (e.g., 670°C) for several hours (e.g., 16 h) to convert the metal oxides to the active metallic state [9].

Synthesis Workflow for Ni-Fe/SBA-15 Catalyst

Protocol 2: Synthesis and Testing of Ni-Co/Mg(Al)O Catalysts from Hydrotalcite Precursors

This protocol outlines the preparation of Ni-Co bimetallic catalysts derived from hydrotalcite-like precursors, which exhibit high performance and well-defined properties for steam reforming of tar impurities [9].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Cation Solution: Nitrate salts of Nickel (Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O), Cobalt (Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O), Magnesium (Mg(NO₃)₂·6H₂O), and Aluminum (Al(NO₃)₃·9H₂O) dissolved in deionized water.

- Anion Solution: Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and Sodium carbonate (Na₂CO₃) dissolved in deionized water.

- pH Adjuster: Nitric acid (HNO₃, 68%).

Procedure:

- Co-precipitation of Hydrotalcite Precursor: a. Prepare a cation solution by dissolving stoichiometric amounts of the nitrate salts in 400 mL deionized water to maintain a (Ni + Co + Mg)/Al molar ratio of 6/2. b. Prepare an anion solution by dissolving NaOH and a 50 mol% excess of Na₂CO₃ in 400 mL deionized water. c. Pump the anion solution into the stirred cation solution at a controlled rate (e.g., 200 mL/h). d. Maintain the reaction mixture at 80°C and adjust the pH to 8–9 using HNO₃. e. Age the resulting slurry overnight (~16 h) at 80°C. f. Cool to room temperature, recover the precipitate by vacuum filtration, and wash extensively with deionized water until the filtrate pH is neutral. g. Dry the precursor overnight at 80°C [9].

Calcination to Form Mixed Oxide Catalyst: a. Place the dried hydrotalcite precursor in a furnace. b. Heat to 600°C at a ramp rate of 5°C/min and hold for 6 hours in a flow of air (e.g., 60 NmL/min) to form the final Ni-Co/Mg(Al)O mixed oxide catalyst [9].

Catalyst Testing in Steam Reforming: a. Load a small amount of catalyst (e.g., 10.0 mg, sieved to 75–150 μm) into a reactor, diluted with an inert material like α-Al₂O₃. b. Reduce the catalyst in situ in a 50% H₂/Ar stream at 670°C for 16 hours. c. Switch to the model syngas feed (e.g., containing CH₄, H₂, CO, CO₂, N₂) and introduce steam and model tar compounds (e.g., toluene, 1-methylnaphthalene, phenol) via a syringe pump. d. Operate at atmospheric pressure, varying parameters such as temperature (650–800°C), steam-to-carbon ratio (2.0–5.0), and tar loading (10–30 g/Nm³). e. Analyze effluent gases and condensable products using gas chromatography (GC) and GC-MS [9].

Protocol 3: Plasma-Enhanced CO2 Reforming of Tar using Nix-Fey/Al2O3 Catalysts

This protocol details the testing of Ni-Fe catalysts in a dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) non-thermal plasma reactor for low-temperature CO2 reforming of tar, demonstrating a novel approach to process intensification [1].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Catalyst: Nix-Fey/Al2O3 catalysts with varying Ni/Fe molar ratios (e.g., 3:1, 1:1, 1:3).

- Tar Model Compound: Toluene.

- Reforming Agent: Carbon dioxide (CO₂).

Procedure:

- Catalyst Preparation: a. Prepare a series of Nix-Fey/Al2O3 catalysts with fixed total metal loading but varying Ni/Fe molar ratios via impregnation or co-precipitation. b. Dry and calcine the catalysts at appropriate temperatures (e.g., 500°C) to form the active phases [1].

Plasma-Catalytic Reactor Setup: a. Place the catalyst in the discharge zone of a DBD plasma reactor. b. Maintain the reactor at a low temperature (e.g., 250°C) and ambient pressure.

Reaction and Analysis: a. Feed a mixture of toluene vapor and CO₂ into the reactor, controlling the CO₂/C7H8 molar ratio (e.g., 1.5). b. Apply a range of discharge powers to generate the non-thermal plasma. c. Analyze the gaseous products using online GC to determine toluene conversion and the selectivity of H₂ and CO [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Bimetallic Catalyst Synthesis and Testing

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nickel Nitrate Hexahydrate | Active metal precursor for C-C bond cleavage and tar cracking [4]. | Ni-Fe/SBA-15 [22], Ni-Co/Mg(Al)O [9]. |

| Iron Nitrate Nonahydrate | Promoter metal precursor; enhances carbon resistance via redox properties and alloy formation [1] [22]. | Nix-Fey/Al2O3 [1], Ni-Fe/Palygorskite [21]. |

| Cobalt Nitrate Hexahydrate | Promoter metal precursor; improves cracking capacity and catalytic activity, especially at lower temperatures [9] [4]. | Ni-Co/Mg(Al)O catalysts [9]. |

| Triblock Copolymer P123 | Structure-directing agent for synthesizing ordered mesoporous SBA-15 silica support [22]. | Synthesis of SBA-15 support [22]. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Dispersing and capping agent to prevent agglomeration, yielding highly dispersed nano-catalysts [22]. | Ni-Fe/SBA-15 synthesis [22]. |

| Toluene / Naphthalene | Model tar compounds representing single-ring and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in biomass tar [21] [1] [9]. | Catalyst screening in reforming reactions [21] [1]. |

| Hydrotalcite Precursors | Layered double hydroxide precursors forming mixed oxides with high surface area and stable metal dispersion upon calcination [9]. | Ni-Co/Mg(Al)O catalyst synthesis [9]. |

In catalyst design for biomass gasification and tar reforming, achieving high efficiency and stability requires a deep understanding of the catalyst's structure-activity relationship and the reaction mechanism at the atomic level. Advanced characterization techniques—specifically in situ Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy (DRIFTS), X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS), and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)—provide powerful, complementary tools for obtaining such mechanistic insights. These techniques enable researchers to probe catalytic surfaces, analyze electronic and coordination structures, and visualize morphological features under operational conditions, moving beyond static observations to dynamic monitoring of catalytic processes [5] [23] [24]. This document outlines detailed application notes and standardized protocols for employing these techniques within biomass tar reforming research.

The table below summarizes the core functionalities, applications, and technical aspects of the three characterization techniques.

Table 1: Comparative overview of advanced characterization techniques

| Technique | Core Information Provided | Primary Applications in Tar Reforming | Spatial Resolution | Detection Limits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Situ DRIFTS | Identification of surface-adsorbed reaction intermediates and species, functional groups, and reaction pathways [5]. | Identifying intermediate species during tar (e.g., toluene, phenol) cracking and reforming; probing active sites and deactivation (e.g., coke formation) [5]. | ~1-10 µm (macroscopic surface area) | Sub-monolayer sensitivity for surface species. |

| XAS (XANES/EXAFS) | Oxidation state (XANES), elemental composition, local coordination environment, bond distances, and coordination numbers (EXAFS) [23]. | Determining the electronic state and coordination of active metals (e.g., Ni, Fe) in catalysts; identifying alloy formation in bimetallic systems (e.g., Ni-Fe) [5] [23] [1]. | ~1 µm (bulk-sensitive) | 0.1-1 at.% for most elements. |

| TEM/AC-STEM | Morphology, particle size distribution, dispersion, crystallinity (HR-TEM), and elemental mapping (STEM-EDS) [23] [24]. | Visualizing metal nanoparticle dispersion, sintering, and carbon nanotube/filament formation leading to catalyst deactivation [5] [23]. | ~0.05 nm (sub-atomic) for AC-STEM [23]. | Single atoms detectable via HAADF-STEM [23]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for In Situ DRIFTS of Tar Reforming Reactions

1. Objective: To identify the surface intermediates and reaction pathways during the steam reforming of toluene (a model tar compound) over a Ni-Fe/Al₂O₃ catalyst.

2. Research Reagent Solutions: Table 2: Essential materials for in situ DRIFTS experiments

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Sample | ~50 mg, powdered Ni-Fe/Al₂O₃, sieved to <100 µm [1]. | The solid catalyst being investigated for its surface chemistry. |

| Toluene | Analytical standard (>99.9% purity) [1]. | Model tar compound representing biomass tar. |

| Water (H₂O) | HPLC grade, degassed. | Source of steam for steam reforming reactions. |

| Inert Gas | High-purity Argon (Ar) or Nitrogen (N₂), 99.999%. | Purge gas and carrier gas for creating an inert atmosphere. |

| Reaction Gas | 10% H₂ in Ar (for reduction), 5% H₂O in Ar (for reaction). | Pre-treatment and reaction gas mixtures. |

| DRIFTS Cell | High-temperature, environmental chamber with ZnSe windows. | Allows for controlled temperature and atmosphere during IR measurement. |

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Sample Loading. Place the catalyst powder into the sample cup of the high-temperature DRIFTS cell. Ensure a smooth, level surface for optimal diffuse reflectance.

- Step 2: In Situ Pre-treatment. Heat the sample to 500°C under a 10% H₂/Ar flow (30 mL/min) for 1 hour to reduce the metal oxides (NiO, Fe₂O₃) to their metallic states [1]. Cool to the desired reaction temperature (e.g., 400-600°C).

- Step 3: Background Collection. Under a continuous flow of inert Ar at the reaction temperature, collect a background single-beam spectrum.

- Step 4: Reaction Initiation & Data Acquisition. Switch the gas flow to a mixture of Ar saturated with H₂O and toluene vapor (e.g., using a saturator held at 30°C). Immediately begin collecting time-resolved IR spectra (e.g., 4 cm⁻¹ resolution, 32 scans per spectrum) over the course of the reaction (e.g., 60 minutes).

- Step 5: Data Processing. Convert the collected single-beam spectra to absorbance units using the background spectrum. Analyze the spectra for the appearance and disappearance of absorption bands corresponding to surface species (e.g., carbonates, formates, carbonyls, coke precursors) [5].

Diagram 1: In Situ DRIFTS Workflow

Protocol for XAS Analysis of Bimetallic Catalysts

1. Objective: To determine the oxidation state and local coordination environment of Ni and Fe in a fresh and spent Nix-Fey/Al₂O₃ catalyst.

2. Research Reagent Solutions: Table 3: Essential materials for XAS experiments

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Sample | ~100 mg, powdered, pressed into a pellet for transmission mode [23]. | The material under investigation for its electronic and atomic structure. |

| Reference Foils | High-purity Ni and Fe metal foils. | For energy calibration of the X-ray beam. |

| Ionization Chambers | Standard for synchrotron beamlines. | Detectors for incident (I0) and transmitted (I1) X-ray intensity. |

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Sample Preparation. Homogenize the catalyst powder and press it into a self-supporting pellet of appropriate thickness to achieve an edge jump (Δμx) of ~1 for the element of interest.

- Step 2: Data Collection. Perform the experiment at a synchrotron beamline. Collect data in transmission mode for the metal foils and in fluorescence mode for the catalyst samples if metal loading is low.

- XANES Region: Collect data around the absorption edge of the element (e.g., Ni K-edge at 8333 eV, Fe K-edge at 7112 eV) with fine energy steps (0.3-0.5 eV) to resolve pre-edge and edge features.

- EXAFS Region: Collect data from ~50 eV below the edge to ~15 k (Å⁻¹) above the edge [23].

- Step 3: Data Processing.

- XANES: Normalize the absorption spectra and compare the edge position and shape with reference compounds (NiO, Ni foil, Fe₂O₃, Fe foil) to determine average oxidation states.

- EXAFS: Extract the χ(k) function, Fourier transform it to R-space, and fit the data using theoretical models to obtain coordination numbers, bond distances, and disorder factors for the first coordination shells (e.g., Ni-Ni, Ni-Fe, Ni-O) [23] [1].

- Step 4: In Situ/Operando Option. For dynamic studies, place the pellet in an in situ cell, reduce it under H₂ flow at high temperature, and collect data under reaction conditions (e.g., in a flow of CO₂ and toluene) [5].

Diagram 2: XAS Analysis Workflow

Protocol for TEM Analysis of Catalyst Morphology and Deactivation

1. Objective: To characterize the morphology, metal particle size distribution, and evidence of deactivation (coking, sintering) in a spent tar reforming catalyst.

2. Research Reagent Solutions: Table 4: Essential materials for TEM analysis

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Sample | Powder, few milligrams. | The material to be imaged at high resolution. |

| Ethanol | Anhydrous, 200 proof. | Solvent for dispersing the catalyst powder. |

| Lacey Carbon Grid | 300-mesh copper or gold grid. | Electron-transparent support film for the sample. |

| Ultrasonic Bath | Standard laboratory cleaner. | For dispersing catalyst powder in solvent. |

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Sample Preparation. Disperse a small amount of catalyst powder in ethanol via gentle ultrasonication for 10-30 seconds to separate particles. Drop-cast a small volume (~5 µL) of the suspension onto a lacey carbon TEM grid and allow it to dry in air.

- Step 2: Microscope Setup. Load the grid into the TEM holder. For aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM, align the microscope according to standard protocols.

- Step 3: Imaging and Analysis.

- Low-Magnification TEM: Survey the grid at various locations to assess overall morphology and identify representative areas.

- HR-TEM: Acquire high-resolution images to observe lattice fringes of the support (e.g., γ-Al₂O₃) and metal nanoparticles, confirming crystallinity [1].

- HAADF-STEM & EDS Mapping: In STEM mode, acquire Z-contrast HAADF images where brighter spots correspond to heavier atoms (e.g., Ni/Fe). Perform energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping to visualize the spatial distribution of Ni, Fe, Al, and O elements, confirming the formation of bimetallic particles or alloys [23] [1].

- Step 4: Post-Processing. Use image analysis software to measure the particle size distribution from multiple HAADF-STEM images. Identify and document deactivation features such as agglomerated (sintered) metal particles and filamentous or encapsulating carbon deposits [5] [25].

Diagram 3: TEM/STEM Analysis Workflow

Integrated Workflow for Comprehensive Catalyst Characterization

A powerful approach in modern catalyst design involves the correlated use of these techniques on the same catalyst samples to build a complete picture from atomic structure to macroscopic function.

Diagram 4: Integrated Characterization Approach

The targeted application of in situ DRIFTS, XAS, and TEM provides an unparalleled toolkit for deconstructing the complex mechanisms at play in biomass tar reforming catalysts. By following the detailed protocols outlined herein, researchers can systematically uncover the nature of active sites, track reaction pathways in real-time, and identify the root causes of catalyst deactivation. Integrating these insights is paramount for the rational design of more active, selective, and durable next-generation catalysts, ultimately advancing the efficiency and commercial viability of biomass gasification technologies.

Carbon-based catalysts (CBCs) represent a class of materials derived from biomass or other carbonaceous sources that exhibit remarkable multifunctionality in biomass gasification systems. These catalysts simultaneously address two critical challenges in syngas production: tar contamination and CO₂ emissions. Their intrinsic catalytic activity drives tar cracking/reforming and water-gas shift reactions, while their tunable porous structures and surface chemistries enable in-situ CO₂ adsorption [5]. This dual functionality positions CBCs as pivotal materials for advancing efficient, low-carbon biomass gasification technologies, particularly in sorption-enhanced gasification (SEG) configurations that achieve higher hydrogen yield and purity while concentrating CO₂ for capture [5].

The following diagram illustrates the multifunctional role of CBCs in a biomass gasification system, integrating both catalytic tar reforming and CO₂ capture processes:

Mechanisms of Multifunctionality

Tar Cracking and Reforming Mechanisms

CBCs facilitate tar decomposition through both physical and chemical pathways. The hierarchical pore structure of advanced CBCs physically adsorbs heavy tar compounds (e.g., fluorene), while inherent mineral species (e.g., Ca, Al, K) catalytically reform light tar components (e.g., phenol, toluene) [5]. The catalytic reforming process involves breaking C–C and C–H bonds in stable aromatic hydrocarbons, with the carbon surface acting as a catalyst to produce H₂, CO, and lighter hydrocarbons [26].

Ding et al. demonstrated that activated biochar (A-biochar) catalysts achieved 96.4% tar conversion through this combined approach [5]. The presence of oxygenated functional groups on the carbon surface further enhances radical reactions that initiate tar decomposition, while doped heteroatoms (e.g., N, S) create active sites that lower the activation energy required for tar reforming [5].

In-Situ CO₂ Capture Mechanisms