AI and Robotics in Catalyst Discovery: From Self-Driving Labs to Clinical Breakthroughs

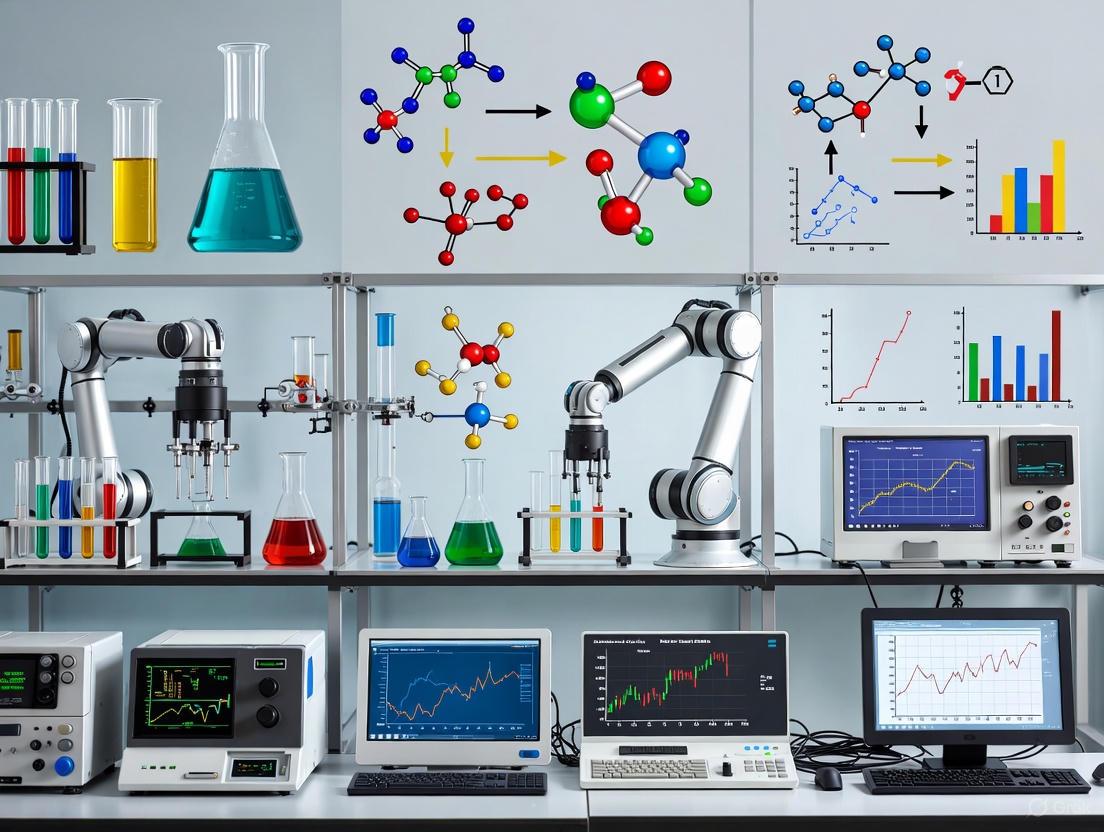

This article explores the transformative integration of artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and advanced data science into catalyst discovery, a field critical for pharmaceutical development and sustainable energy.

AI and Robotics in Catalyst Discovery: From Self-Driving Labs to Clinical Breakthroughs

Abstract

This article explores the transformative integration of artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and advanced data science into catalyst discovery, a field critical for pharmaceutical development and sustainable energy. We examine the foundational shift from manual, trial-and-error methods to autonomous, self-driving laboratories (SDLs) that operate with minimal human oversight. The scope covers core methodological components—from robotic hardware and AI-driven decision-making to real-world applications in drug development and electrocatalyst discovery. It also addresses key challenges in optimization, data scarcity, and model generalizability, while providing a comparative analysis of validation frameworks and performance metrics. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current advancements and future trajectories for accelerating biomedical innovation.

The Paradigm Shift: From Manual Experiments to Autonomous Discovery

Defining Autonomous Catalyst Discovery and Self-Driving Labs (SDLs)

Autonomous discovery represents a transformative paradigm in scientific research, where artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and automation converge to plan, execute, and analyze experiments with minimal human intervention [1]. At the heart of this paradigm are Self-Driving Labs (SDLs)—fully integrated research systems that combine automated instrumentation, data infrastructures, and AI-guided decision-making to enable closed-loop, iterative experimentation [2] [3]. In the specific domain of catalysis, autonomous catalyst discovery refers to the application of these SDLs to rapidly identify and optimize new catalytic materials and reactions, dramatically accelerating research that is fundamental to chemical manufacturing, environmental sustainability, and energy applications [2].

These systems function as robotic co-pilots for scientists, automating the entire research workflow from initial hypothesis generation to experimental execution, data analysis, and subsequent experimental planning [3]. By leveraging AI to dynamically learn from outcomes, SDLs continuously refine their understanding and exploration strategies, enabling them to navigate complex experimental parameter spaces with exceptional efficiency [4]. This approach shifts the traditional, human-centered trial-and-error methodology toward an information-rich, data-driven process that can achieve discoveries 10 to 100 times faster than conventional methods, with the potential to reach 1,000-fold acceleration in the future [3].

Core Components and Workflows of SDLs

The operational framework of a Self-Driving Lab is built upon three foundational pillars that work in concert: automated hardware, computational models, and intelligent decision-making algorithms.

Core Component Table

Table 1: Essential Components of a Self-Driving Lab for Catalyst Discovery

| Component Category | Specific Examples | Function in Autonomous Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Automation & Robotics | Fixed-in-place robots [1], Mobile human-like robots [1], High-throughput synthesis platforms [2] | Executes repetitive physical tasks such as liquid handling, material synthesis, and sample characterization with high precision and reproducibility. |

| AI & Decision-Making | Bayesian optimization [4], Reinforcement learning [5], Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) [6] | Plans experiments by predicting the most informative conditions to test, thereby minimizing the number of trials needed to reach a goal. |

| Data Infrastructure | FAIR data principles [4], Cloud-based data storage [4], Scientific Large Language Models (LLMs) [4] | Manages large volumes of experimental data, ensuring it is Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable for both humans and AI models. |

Standardized Workflow for Autonomous Catalyst Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the closed-loop, iterative process that defines the operation of a Self-Driving Lab.

Diagram 1: Autonomous Catalyst Discovery Workflow.

This workflow operates as a continuous cycle:

- Objective Definition: A human researcher defines the primary goal, such as discovering a catalyst that maximizes yield for a specific reaction [2].

- AI Proposal: An AI algorithm, such as a Bayesian optimizer, analyzes all existing data and proposes a set of experimental conditions (e.g., catalyst composition, temperature, pressure) that are most likely to advance toward the goal [4] [6].

- Robotic Execution: Automated platforms and robots perform the material synthesis and catalytic testing, ensuring high reproducibility and operating 24/7 [1] [2].

- Data Analysis: Integrated analytical instruments automatically collect and process results, feeding structured data back to the AI [3].

- AI Learning: The AI model incorporates the new results, updates its internal understanding of the catalyst landscape, and uses this refined knowledge to propose the next most informative experiment [4]. This loop continues until the performance objective is achieved.

Quantitative Performance and Application Data

SDLs have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in accelerating materials and catalyst research. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from real-world implementations.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Self-Driving Labs in Materials and Catalyst Research

| Application Area | SDL System / AI | Key Performance Achievement | Experimental Throughput / Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy-Absorbing Materials | MAMA BEAR (BU) [4] | Discovered a material with 75.2% energy absorption efficiency, a record high. | Over 25,000 experiments conducted autonomously. |

| Mechanical Structures | BU SDL with Cornell Algorithms [4] | Achieved 55 J/g energy absorption, doubling the previous benchmark of 26 J/g. | Rapid evaluation of novel Bayesian optimization algorithms. |

| Electronic Polymer Films | Polybot (Argonne) [1] | Produced high-conductivity, low-defect electronic polymer thin films. | AI-driven automation of material synthesis and testing. |

| Chip Design (TPU) | AlphaChip (Google) [5] | Generated superhuman chip layouts used in commercial hardware. | Reduced design time from months to hours. |

Experimental Protocols for SDL-Based Catalyst Discovery

Protocol 1: Bayesian Optimization for Catalyst Screening

This protocol is adapted from workflows used to discover high-performance energy-absorbing materials and can be adapted for catalyst optimization [4].

Objective: To efficiently identify the catalyst composition and reaction conditions that maximize product yield within a predefined chemical space.

Materials and Reagents:

- Precursor Solutions: Stocks of metal salts and ligand solutions.

- Solvent Library: A range of polar and non-polar solvents.

- Substrates: High-purity reactants for the catalytic reaction.

- Analytical Standards: Pure samples for GC/MS or HPLC calibration.

Procedure:

- Define Search Space: Establish the parameters and their bounds (e.g., metal molar ratio (0-100%), ligand concentration (0.1-10 mol%), temperature (25-150 °C), reaction time (1-24 h)).

- Initialize with Design of Experiments (DoE): Perform a small set of initial experiments (e.g., 10-20) using a space-filling design like Latin Hypercube Sampling to gather baseline data.

- Build Surrogate Model: Train a Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) model on the collected data to create a statistical surrogate of the catalyst performance landscape [6].

- Select Subsequent Experiment: Use an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) to identify the single set of conditions that promises the largest performance gain or information gain.

- Execute Experiment Automatically: The robotic platform prepares the catalyst and runs the reaction at the specified conditions.

- Analyze and Update: Automatically quantify the product yield and feed the result back to the GPR model. Repeat from step 4 until a performance target is met or the experimental budget is exhausted.

Protocol 2: Closed-Loop Kinetic Profiling of Catalytic Reactions

This protocol leverages AI and robotics for in-depth mechanistic studies, crucial for catalyst development [2] [6].

Objective: To autonomously map the reaction kinetics and understand the mechanism of a catalytic process.

Materials and Reagents:

- Catalyst Library: A series of related catalyst candidates.

- Reactant Solutions: Prepared at various concentrations.

- Quenching Agents: To stop reactions at precise times for analysis.

- Internal Standards: For accurate quantitative analysis.

Procedure:

- Automated Time-Point Sampling: The robotic system initiates the reaction and automatically withdraws aliquots at pre-defined time intervals.

- High-Throughput Analysis: Each aliquot is automatically quenched and injected into an online GC or HPLC for analysis.

- Data Stream Integration: Concentration-time data for each experiment is automatically parsed and stored in a central database.

- Kinetic Model Proposal: An AI agent (potentially an LLM fine-t on chemical knowledge) suggests plausible kinetic models (e.g., Langmuir-Hinshelwood, Eley-Rideal) based on the reaction data [6].

- Model Fitting and Validation: The system fits the proposed models to the data, comparing goodness-of-fit metrics (e.g., AIC, BIC) to identify the most probable mechanism.

- Design Optimal Discriminatory Experiment: The AI uses the model uncertainties to design a new experiment (e.g., at specific concentrations) whose results will best distinguish between competing kinetic models.

- Iterate: The loop (steps 1-6) continues until the kinetic model is sufficiently validated and the parameters are determined with high confidence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent and Solution Essentials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Autonomous Catalysis SDLs

| Item | Function / Role in Autonomous Workflow |

|---|---|

| Modular Reactor Systems | Enable rapid testing of reactions under different conditions (pressure, temperature, flow) with minimal manual reconfiguration [2]. |

| High-Throughput Characterization | Integrated analytical tools (e.g., inline spectroscopy, autosamplers for GC/LC) that provide real-time or rapid-turnaround data for closed-loop decision-making [3]. |

| FAIR-Compliant Database | A centralized digital repository that adheres to Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable principles, ensuring all experimental data is structured for AI consumption [4]. |

| AI Planning Software | Core algorithms (e.g., for Bayesian optimization or reinforcement learning) that direct the experimental campaign by deciding which experiment to perform next [4] [5]. |

| Precursor Chemical Libraries | Comprehensive, well-organized collections of chemical building blocks (metal salts, ligands, substrates) that the robotic system can access and dispense automatically [2]. |

Implementation and Strategic Considerations

System Architecture and Human-in-the-Loop Design

While fully autonomous operation is the goal, human oversight remains critical. The most effective SDLs are designed for human-AI-robot collaboration [2]. Researchers provide high-level direction, validate machine-generated hypotheses, and oversee safety. The architecture must also prioritize data quality and curation, as AI models are only as good as the data they train on [3]. Implementing a cloud-connected, community-driven platform, as explored at Boston University, can transform an SDL from an isolated instrument into a shared resource, amplifying its impact [4].

Addressing Key Challenges

Deploying a functional SDL requires overcoming several interdisciplinary challenges:

- Hardware Reliability and Integration: Creating robust, interoperable systems that execute complex workflows with high precision and minimal downtime is a significant engineering hurdle [3].

- Workforce Development: A skilled workforce capable of designing, maintaining, and operating these sophisticated platforms is essential for widespread adoption [3].

- Legal and Safety Standards: Establishing clear policies for safe handling of hazardous materials, intellectual property rights, and responsible AI use is fundamental for building trust and ensuring responsible deployment [3].

The integration of AI, robotics, and automation into the scientific process marks a fundamental shift in research methodology. Autonomous catalyst discovery within Self-Driving Labs is poised to dramatically accelerate the development of new materials and chemicals, offering a powerful solution to address urgent global challenges in energy, sustainability, and healthcare [3].

The empirical process of scientific discovery, traditionally guided by researcher intuition and characterized by lengthy timelines, is undergoing a fundamental transformation. The urgent challenges in energy conversion and sustainable raw material use now demand radically new approaches in fields like catalysis research [7]. Autonomous discovery systems, particularly self-driving laboratories (SDLs), have emerged as a powerful strategy to meet this need by dramatically accelerating the pace of materials and chemical innovation. These systems integrate artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and automation technologies into a continuous closed-loop cycle, enabling efficient scientific experimentation with minimal human intervention [8]. By turning processes that once took months of trial and error into routine high-throughput workflows, autonomous laboratories represent a paradigm shift in experimental science, potentially reducing discovery timelines from decades to mere years.

The core power of these systems lies in their ability to operate as continuous closed loops. In an ideal implementation, an AI model trained on literature data and prior knowledge generates initial synthesis schemes for a target molecule or material. Robotic systems then automatically execute every step of the synthesis recipe, from reagent dispensing and reaction control to product collection and analysis. Characterization data are analyzed by software algorithms or machine learning models, which then propose improved synthetic routes using techniques like active learning and Bayesian optimization [8]. This tight integration of design, execution, and data-driven learning minimizes downtime between manual operations, eliminates subjective decision points, and enables rapid exploration of novel materials and optimization strategies at unprecedented scales.

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

The acceleration enabled by autonomous discovery systems is demonstrated by concrete experimental results across multiple domains, from materials science to heterogeneous catalysis. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent implementations:

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of Autonomous Discovery Systems

| System/Platform | Application Domain | Key Performance Metrics | Experimental Throughput | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAMA BEAR (BU) | Energy-absorbing materials | Achieved 75.2% energy absorption; discovered structures absorbing 55 J/g (doubling previous 26 J/g benchmark) | >25,000 experiments conducted | [4] |

| A-Lab (2023) | Solid-state synthesis | Synthesized 41 of 58 predicted materials (71% success rate) over 17 days of continuous operation | 58 materials attempted | [8] |

| AFE with Active Learning | Oxidative coupling of methane (OCM) | MAE of 1.69% in C2 yields during training; 1.73% in cross-validation | 80 new catalysts added over 4 active learning cycles | [9] |

| Automatic Feature Engineering | Ethanol to butadiene conversion | MAE of 3.77%-3.93% in butadiene yield predictions | Applied to supported multi-element catalyst datasets | [9] |

| Automatic Feature Engineering | Three-way catalysis | MAE of 11.2°C-11.9°C in T50 of NO conversion | Applied to supported multi-element catalyst datasets | [9] |

These quantitative results demonstrate the dual advantage of autonomous systems: significantly increased experimental throughput combined with enhanced discovery efficiency. The MAMA BEAR system's discovery of materials with unprecedented mechanical energy absorption (55 J/g) opens new possibilities for advanced lightweight protective equipment [4], while the A-Lab's ability to successfully synthesize 71% of targeted materials demonstrates the feasibility of autonomous materials discovery at scale [8].

The performance of AI-driven catalyst design is particularly notable when working with small datasets, which are common in experimental catalysis research. Automatic Feature Engineering (AFE) techniques have achieved remarkable accuracy in predicting catalytic performance across three types of heterogeneous catalysis: oxidative coupling of methane, conversion of ethanol to butadiene, and three-way catalysis [9]. The mean absolute error (MAE) values obtained through AFE were significantly smaller than the span of each target variable and comparable to respective experimental errors, enabling effective catalyst optimization with limited data.

Experimental Protocols for Autonomous Catalyst Discovery

Protocol: Autonomous Workflow for Solid-State Materials Synthesis

Based on: A-Lab Implementation for Inorganic Materials [8]

- Objective: To autonomously synthesize and optimize novel, theoretically stable inorganic materials predicted by computational methods.

- Primary Components:

- Target Selection: Novel materials are selected using large-scale ab initio phase-stability databases from the Materials Project and Google DeepMind.

- Synthesis Recipe Generation: Natural-language models trained on literature data propose initial synthesis recipes, including precursor selection and temperature parameters.

- Robotic Synthesis: Automated solid-state synthesis platforms handle weighing, mixing, and calcination of precursor powders.

- Phase Identification: X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns are analyzed by machine learning models (convolutional neural networks) for phase identification and quantification.

- Active Learning Optimization: The ARROWS³ algorithm uses results from previous iterations to propose improved synthesis routes for failed or suboptimal syntheses.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Computational targets are imported into the autonomous workflow management system.

- AI-generated synthesis recipes are translated into robotic execution commands.

- Robotic systems execute powder handling, mixing, and heat treatment according to recipe parameters.

- Synthesized materials are automatically transported to XRD instrumentation for characterization.

- ML models analyze diffraction patterns to determine synthesis success and product purity.

- Active learning algorithms update the recipe models based on outcomes.

- The cycle continues with improved recipes for failed targets or proceeds to new targets.

- Key Parameters:

- Success Criterion: Successful synthesis of target material with correct crystal structure as determined by XRD.

- Optimization Variables: Precursor identities, precursor ratios, grinding time, heating rates, reaction temperatures, reaction durations.

- Decision Logic: Heuristic rules combined with Bayesian optimization to prioritize synthesis parameter adjustments.

Protocol: Closed-Loop Optimization for Catalyst Design

Based on: Automatic Feature Engineering with Active Learning [9]

- Objective: To discover and optimize multi-element heterogeneous catalysts through iterative experimentation and machine learning.

- Primary Components:

- Automatic Feature Engineering (AFE): Generates numerous candidate features through mathematical operations on general physicochemical properties of catalyst components.

- Feature Selection: Identifies optimal feature subsets that maximize predictive performance in supervised machine learning.

- Active Learning: Combines exploration (farthest point sampling) and exploitation (high-error sampling) to select informative subsequent experiments.

- High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE): Robotic platforms enable rapid preparation and testing of catalyst candidates.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Initialization: Begin with limited catalyst performance dataset (typically <100 observations).

- Feature Engineering:

- Assign primary features using commutative operations (maximum, weighted average) on elemental properties.

- Synthesize higher-order features through mathematical functions to capture nonlinearities.

- Generate 10³-10⁶ candidate features from a library of elemental properties.

- Model Building: Select 5-10 features that minimize cross-validation error using robust regression (Huber regression).

- Experimental Design:

- Select ~90% of next experiments via farthest point sampling in feature space to diversify composition space.

- Select ~10% of next experiments based on highest prediction errors to refine uncertain regions.

- HTE Execution: Prepare and evaluate designed catalysts using automated synthesis and testing platforms.

- Model Update: Incorporate new data and repeat from step 2.

- Key Parameters:

- Regression Method: Huber regression with leave-one-out cross-validation to minimize overfitting.

- Feature Space: 5,568+ first-order features generated from 58 elemental properties via 8 commutative operations and 12 mathematical functions.

- Stopping Criterion: Model convergence (minimal change in cross-validation error) and/or depletion of experimental resources.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Components for Autonomous Catalyst Discovery

| Category | Component | Function & Application | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI/ML Infrastructure | Bayesian Optimization Algorithms | Guides experimental parameter selection by balancing exploration and exploitation; maximizes information gain from each experiment. | MAMA BEAR system for energy-absorbing materials [4] |

| Automatic Feature Engineering (AFE) | Automatically generates and selects relevant physicochemical descriptors from elemental properties without prior catalytic knowledge. | Catalyst design for oxidative coupling of methane, ethanol-to-butadiene conversion [9] | |

| Large Language Models (LLM) | Serves as "brain" for autonomous research: plans experiments, accesses literature, controls robotic systems via natural language. | Coscientist, ChemCrow, and ChemAgents systems [8] | |

| Robotic Hardware | Solid-State Synthesis Platforms | Automated weighing, mixing, and heat treatment of powder precursors for inorganic materials. | A-Lab implementation with robotic furnaces and powder handling [8] |

| Mobile Robot Transport Systems | Free-roaming robots transport samples between specialized instruments (synthesizers, chromatographs, spectrometers). | Modular platform with mobile robots connecting Chemspeed ISynth, UPLC-MS, benchtop NMR [8] | |

| Liquid Handling Robots | Precise dispensing of liquid reagents for solution-phase synthesis and catalyst preparation. | Robotic organic synthesis platforms for cross-coupling reactions [8] | |

| Analytical Integration | In Situ/Operando Characterization | Real-time monitoring of catalysts under working conditions to identify active species and mechanistic pathways. | Essential for autonomous catalyst development [7] |

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) with ML | Automated phase identification and quantification of crystalline materials using machine learning models. | Convolutional neural networks for XRD analysis in A-Lab [8] | |

| Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry | Online analysis of reaction products and yields for organic transformations and catalytic testing. | UPLC-MS systems in modular autonomous platforms [8] | |

| Data Infrastructure | FAIR Data Practices | Ensures data are Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable for community-driven science. | BU Libraries public dataset downloaded 89+ times [4] |

| Cloud-Based Science Portals | Shared platforms for collaborative experimentation, data sharing, and community-driven research. | AI Materials Science Ecosystem (AIMS-EC) portal [4] |

Implementation Challenges and Future Directions

Despite their promising results, autonomous discovery systems face several significant constraints that must be addressed for widespread deployment. The performance of AI models depends heavily on high-quality, diverse data, yet experimental data often suffer from scarcity, noise, and inconsistent sources [8]. Most current autonomous systems and AI models are highly specialized for specific reaction types or materials systems, struggling to generalize across different domains [8]. Hardware limitations also present barriers, as different chemical tasks require different instruments, and current platforms lack modular architectures that can seamlessly accommodate diverse experimental requirements [8].

Looking ahead, several strategic developments will be crucial for advancing autonomous discovery systems. Enhancing AI generalization will require training foundation models across different materials and reactions, using transfer learning to adapt to limited new data [8]. Developing standardized hardware interfaces will allow rapid reconfiguration of different instruments, extending mobile robot capabilities to include specialized analytical modules [8]. Community-driven platforms, inspired by cloud computing models, will open SDLs to broader research communities, accelerating discovery through shared resources and combined knowledge [4]. Finally, addressing data scarcity will necessitate standardized experimental data formats, augmented by high-quality simulation data and uncertainty analysis [8].

As these systems evolve, the role of human researchers will transform rather than diminish. The future of accelerated discovery lies in collaborative human-machine systems where AI and automation handle high-throughput experimentation while researchers contribute creativity, intuition, and strategic oversight [4]. This partnership represents the most promising path for achieving the urgent goal of compressing discovery timelines from decades to years, ultimately enabling rapid solutions to pressing global challenges in energy, sustainability, and human health.

Autonomous discovery systems represent a paradigm shift in scientific research, replacing traditional, human-driven laboratory workflows with integrated, self-driving laboratories. These systems synergistically combine artificial intelligence (AI), advanced robotics, and closed-loop workflows to accelerate the pace of discovery in fields ranging from chemistry and materials science to drug development. By creating a continuous cycle of computational design, robotic execution, and data-driven learning, these platforms can conduct scientific experiments with minimal human intervention, compressing discovery timelines that traditionally required decades into mere years [8] [10]. This document details the core components, protocols, and practical implementations of these systems, providing researchers with a framework for deploying autonomous discovery in catalyst development and beyond.

Core Architectural Components

The architecture of an autonomous laboratory is built upon three interconnected technological pillars that form a continuous, adaptive discovery engine.

Artificial Intelligence: The Central Decision-Maker

AI serves as the cognitive center of autonomous laboratories, encompassing several specialized functions:

- Experimental Planning and Design: AI models, particularly large language models (LLMs), can design novel synthesis schemes and predict viable experimental parameters by drawing upon vast scientific literature and existing datasets. Systems like Coscientist and ChemCrow demonstrate LLM-driven agents capable of autonomously planning and controlling robotic operations for chemical experiments [8].

- Knowledge Extraction and Integration: AI systems construct comprehensive biological and chemical representations by fusing multi-modal data. For instance, Insilico Medicine's Pharma.AI platform leverages natural language processing to extract information from over 40 million documents and integrates this with omics data to identify novel therapeutic targets [11].

- Generative Design: Generative models create novel molecular structures or materials configurations optimized for specific properties. Generative adversarial networks (GANs) and reinforcement learning algorithms can design drug-like molecules balanced for potency, metabolic stability, and bioavailability [12] [11].

- Data Analysis and Interpretation: Machine learning models, including convolutional neural networks, automatically interpret complex analytical data, such as X-ray diffraction patterns or NMR spectra, to identify reaction products and quantify yields [8] [13].

Robotic Systems: The Physical Execution Layer

Robotic systems provide the physical interface for conducting experiments with precision and reproducibility:

- Fixed Automation Systems: Integrated robotic workstations handle specific tasks like liquid handling, synthesis, and sample preparation. The A-Lab for solid-state synthesis employs robotic arms for weighing, mixing, and pelletizing precursor powders, followed by automated transfer to furnaces for heating [8].

- Mobile Robotics: Free-roaming mobile robots transport samples between fixed instrumentation stations. The modular platform demonstrated by Dai et al. uses mobile robots to operate a synthesizer, UPLC-MS system, and benchtop NMR, creating a flexible laboratory configuration [8].

- Integrated Analytical Instrumentation: Automated systems incorporate analytical techniques including ultraperformance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and other characterization methods that provide real-time feedback on experimental outcomes [8] [13].

- Additive Manufacturing: High-resolution 3D printing enables rapid fabrication of custom reactor geometries with complex internal structures optimized for specific catalytic applications [13].

The Closed-Loop Workflow: Integrating Components

The true power of autonomous laboratories emerges from the tight integration of AI and robotics into a continuous Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) cycle:

- Design Phase: AI models propose candidate materials, molecules, or experimental conditions based on prior knowledge and optimization algorithms.

- Make Phase: Robotic systems automatically execute the synthesis, preparation, or fabrication of the proposed designs.

- Test Phase: Integrated analytical instruments characterize the products and measure their properties or performance.

- Analyze Phase: AI processes the experimental results, updates its models, and uses active learning or Bayesian optimization to propose improved designs for the next iteration [8] [11].

This closed-loop approach minimizes downtime between experiments, eliminates subjective decision points, and enables rapid exploration of parameter spaces that would be intractable through manual methods.

Case Study & Experimental Protocol: The Reac-Discovery Platform for Catalytic Reactor Optimization

The Reac-Discovery platform exemplifies the application of autonomous systems to catalyst and reactor discovery, specifically for multiphase continuous-flow reactions [13].

Reac-Discovery is a semi-autonomous digital platform that integrates the design, fabrication, and optimization of catalytic reactors with periodic open-cell structures (POCS). It aims to simultaneously optimize both reactor geometry (topology) and process parameters to enhance performance in complex multiphasic transformations, where variables such as surface-to-volume ratio, flow patterns, and thermal management strongly influence heat and mass transfer [13].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Module 1: Reactor Geometry Generation (Reac-Gen)

- Objective: Digitally construct and parametrically define advanced reactor geometries.

- Procedure:

- Select a base structure from the predefined library of 20 surface equations, including Triply Periodic Minimal Surfaces like Gyroid, Schwarz, and Schoen-G.

- Set the three key parameters that define the topology using implicit equations (e.g., for a Gyroid:

sin(x)·cos(y) + sin(y)·cos(z) + sin(z)·cos(x) = L):- Size (S): Defines the spatial boundaries and number of periodic units.

- Level Threshold (L): Sets the isosurface cutoff, controlling porosity and wall thickness.

- Resolution (R): Specifies sampling point density, controlling geometric fidelity.

- Execute the algorithm to generate the 3D model and compute geometric descriptors (void area, hydraulic diameter, local porosity, specific surface area, wetted perimeter, total surface area, free volume, tortuosity).

Module 2: Reactor Fabrication (Reac-Fab)

- Objective: Translate digital designs into physical reactors.

- Procedure:

- Validate the structural printability using a dedicated ML model to avoid fabrication failures.

- Employ stereolithography (SLA) for high-resolution 3D printing of the reactor structure.

- Functionalize the printed structure with the catalytic material (e.g., through immobilization of molecular catalysts or coating with catalytic suspensions).

Module 3: Evaluation and Optimization (Reac-Eval)

- Objective: Autonomously evaluate reactor performance and refine parameters.

- Procedure:

- Install multiple 3D-printed reactors in the parallel self-driving laboratory setup.

- Initiate continuous-flow reactions with real-time monitoring using benchtop NMR spectroscopy.

- Vary key process descriptors (temperature, gas/liquid flow rates, concentration) according to an active learning or Bayesian optimization algorithm.

- Collect reaction conversion and yield data from NMR analysis.

- Train two interconnected ML models:

- A process optimization model to identify optimal reaction conditions.

- A reactor geometry refinement model to correlate topological descriptors with performance and suggest improved geometries.

- Feed the results back to Reac-Gen to initiate the next design iteration.

Key Performance Metrics and Outcomes

Table 1: Quantitative Results from Reac-Discovery Platform Application [13]

| Reaction | Key Optimized Parameter | Achieved Performance | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogenation of Acetophenone | Space-Time Yield (STY) | Significant enhancement over conventional reactors | Demonstrated platform efficacy for a benchmark transformation |

| CO₂ Cycloaddition to Epoxides | Space-Time Yield (STY) | Highest reported STY for a triphasic reaction using immobilized catalysts | Validated platform for thermodynamically challenging, industrially relevant reactions |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams illustrate the core closed-loop workflow and the specific architecture of the Reac-Discovery platform.

Generalized Closed-Loop Workflow

Reac-Discovery Platform Architecture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful implementation of autonomous discovery systems requires careful selection of hardware, software, and laboratory infrastructure.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Autonomous Discovery

| Item | Function/Role | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| AI/ML Models for Planning | Generate initial synthesis schemes, predict properties, and plan experiments. | Coscientist LLM agent; Insilico's Chemistry42 for generative molecule design [8] [11]. |

| Robotic Synthesis Workstation | Automates the execution of chemical synthesis with precision and reproducibility. | Chemspeed ISynth synthesizer; A-Lab's robotic arms for solid-state synthesis [8]. |

| Mobile Robots | Transport samples between fixed instruments, enabling flexible lab configurations. | System by Dai et al. using free-roaming robots to connect synthesizer, UPLC-MS, and NMR [8]. |

| Integrated Analytical Instruments | Provide real-time, automated characterization of reaction outcomes and products. | Benchtop NMR for real-time monitoring; UPLC-MS systems; XRD for phase identification [8] [13]. |

| High-Resolution 3D Printer | Fabricates custom reactor geometries with complex internal structures. | Stereolithography (SLA) printer in Reac-Fab module for creating POCS reactors [13]. |

| Data Management Platform | Handles large, multi-modal datasets and facilitates model training and data exchange. | Recursion OS platform managing ~65 petabytes of proprietary biological and chemical data [11]. |

| Optimization Algorithms | Guide the iterative search for optimal conditions or designs using experimental data. | Bayesian optimization; Active learning (e.g., ARROWS3 algorithm in A-Lab) [8]. |

The integration of AI, robotics, and closed-loop workflows constitutes the technological foundation of modern autonomous discovery systems. As demonstrated by platforms like Reac-Discovery and A-Lab, this integration enables a fundamental reimagining of scientific research—shifting from human-guided, sequential investigation to AI-orchestrated, parallel discovery campaigns. While challenges remain, including data scarcity, model generalizability, and hardware interoperability, the continued advancement of these core components promises to dramatically accelerate innovation across catalysis, materials science, and pharmaceutical development. The protocols and architectures detailed herein provide a roadmap for researchers embarking on the development and implementation of these transformative technologies.

The development of autonomous catalyst discovery systems represents a paradigm shift in materials science and pharmaceutical development. This transition from manual, intuition-driven research to automated, data-driven experimentation addresses fundamental challenges in catalyst discovery, where the structural complexity of drug intermediates often renders conventional catalytic methods ineffective [14]. The integration of high-throughput experimentation (HTE) with artificial intelligence (AI) has created a foundation for fully autonomous systems capable of navigating high-dimensional material design spaces beyond human capabilities [15]. These systems have proven particularly valuable in pharmaceutical synthesis, where they solve challenging problems in process chemistry and medicinal chemistry development [14]. This article examines critical lessons from historical HTE and automation approaches, providing detailed application notes and protocols to inform the next generation of autonomous catalyst discovery platforms.

Key Historical Developments and Quantitative Insights

The evolution of chemical high-throughput experimentation demonstrates a clear trajectory toward increased miniaturization, automation, and computational integration. Early HTE systems focused primarily on homogeneous asymmetric hydrogenation using chiral precious-metal catalysts [14]. Success in these early applications motivated expansion to other high-value catalytic chemistries, necessitating significant advances in reactor design, workflow automation, and analytical techniques [14].

Table 1: Evolution of HTE Capabilities in Pharmaceutical Catalyst Discovery

| Development Phase | Primary Screening Focus | Typical Format | Key Technological Enablers | Material Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early HTE (Pre-2010) | Homogeneous hydrogenation | 96-well plates | Predefined catalyst libraries, basic automation | Moderate (mg scale) |

| Intermediate HTE (c. 2010-2017) | Cross-coupling, phase-transfer catalysis | 384-well plates | Advanced reactor design, high-throughput analytics | Improved (μg-mg scale) |

| Advanced HTE (Post-2017) | Photoredox catalysis, C-H functionalization | 1536-well plates | Miniaturization, cheminformatics, "nanoscale" screening | High (nano-μg scale) |

| AI-Driven Autonomous Systems | Multi-objective optimization | Continuous flow/HTE integration | Bayesian optimization, LLMs, robotic workflows | Optimal (minimal material consumption) |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Catalyst Discovery Methodologies

| Discovery Methodology | Time per Catalyst Evaluation | Material Consumption per Experiment | Success Rate for Complex Pharmaceutical Intermediates | Informatics Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Trial-and-Error | Days to weeks | Gram scale | Low (<10%) | Limited to laboratory notebooks |

| Early HTE Approaches | Hours to days | Milligram scale | Moderate (10-30%) | Basic database integration |

| DFT-Guided HTE | Hours | Milligram scale | Improved (30-50%) | Computational screening |

| AI-Empowered Autonomous Discovery | Minutes to hours | Nanogram to microgram scale | High (50-80%) | "Big data" informatics, predictive modeling |

The quantitative progression illustrated in Tables 1 and 2 highlights how early automation enabled the exploration of catalyst design spaces orders of magnitude larger than previously possible. The implementation of "nanoscale" reaction screening in 1536-well plates represented a critical breakthrough, dramatically reducing both time and material requirements while generating data density sufficient for informatics-driven approaches [14]. This evolution continues with AI techniques progressing from classical machine learning to graph neural networks and large language models (LLMs), with LLMs particularly promising for their ability to comprehend textual descriptions of catalyst systems and integrate diverse observable features [16].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Nanoscale Catalyst Screening in 1536-Well Plates for Pharmaceutical Applications

Based on evolved HTE techniques for challenging problems in pharmaceutical synthesis [14]

Setting Up

Pre-experiment Preparation (Timeline: 24 hours before screening)

- Reboot control computer and robotic handling systems to clear memory caches and ensure optimal performance.

- Verify environmental controls: maintain laboratory temperature at 23°C ± 0.5°C and relative humidity at 40% ± 5%.

- Calibrate liquid handling systems using fluorescent dye dilution series, verifying accuracy within 2% coefficient of variation.

- Pre-condition 1536-well plates by inert gas purging (N2 or Ar) for 12 hours to remove oxygen and moisture.

Reagent Preparation (Timeline: 4 hours before screening)

- Prepare catalyst libraries at 100mM concentration in appropriate anhydrous solvents under inert atmosphere.

- Formulate substrate solutions at 50mM concentration with internal standard (0.1mM dodecane for GC-MS analysis).

- Verify solution integrity via UV-Vis spectroscopy, rejecting any solutions with evidence of precipitation or degradation.

Automated Screening Execution

Plate Layout and Liquid Handling

- Program robotic platform to dispense 50nL catalyst solutions using non-contact piezoelectric dispensers.

- Add 100nL substrate solutions to appropriate wells, maintaining inert atmosphere throughout.

- Seal plates with gas-permeable membrane for oxygen-sensitive reactions or solid seals for volatile solvent systems.

- Initiate thermal cycling protocol with precise temperature control (±0.1°C) across the entire plate.

Reaction Monitoring and Quenching

- For time-course experiments, program automated sampling at t=5, 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes.

- Quench reactions by addition of 200nL quenching solution (typically 1% trifluoroacetic acid in acetonitrile).

- Transfer 1μL aliquots from each well to analysis plates using positive displacement capillaries.

High-Throughput Analysis

Analytical Method Integration

- Implement UPLC-MS methods with cycle times of <3 minutes per sample.

- Utilize multi-channel injection systems for parallel analysis of 4-8 samples simultaneously.

- Apply automated data processing with peak integration, identification, and conversion calculations.

Quality Control Measures

- Include control wells with known catalysts in every plate to monitor system performance.

- Implement automated flagging of samples with internal standard deviation >15%.

- Apply background subtraction using blank wells containing all components except catalyst.

Data Management and Analysis

- Experimental Record Keeping

- Automatically log all experimental parameters to centralized database with timestamps.

- Apply cheminformatics analysis using Chemistry Informer Libraries to assess reaction generality.

- Implement Bayesian optimization algorithms to identify promising regions of catalyst space for subsequent iterations.

Exception Handling and Troubleshooting

- Common Issues and Resolution

- Evaporation Effects: If well volumes decrease >10%, increase humidity control or switch to lower vapor pressure solvents.

- Precipitation Events: Automatically flag and exclude wells showing light scattering indicative of precipitation.

- Instrument Drift: Implement periodic recalibration every 100 samples during extended runs.

Protocol: Bayesian Optimization with Gaussian Processes for Autonomous Catalyst Discovery

Based on active learning techniques for handling complex optimization problems [15]

Pre-optimization Setup

Experimental Design Phase

- Define parameter spaces: catalyst composition (5-15 mol%), temperature (25-150°C), pressure (1-50 atm), solvent composition (binary mixtures).

- Establish objective functions: conversion (>80%), selectivity (>90%), turnover number (>1000).

- Set constraints: reaction time (<24h), catalyst cost (<$100/mmol), safety parameters.

Initial Dataset Generation

- Create space-filling design (Sobol sequence) with 20-50 initial data points covering parameter space.

- Execute initial experiments using automated protocols (Section 3.1).

- Validate data quality, removing statistical outliers with studentized residuals >3.0.

Optimization Loop Execution

- Gaussian Process Model Updating

- Update surrogate model with all available data using Matern 5/2 kernel function.

- Calculate acquisition function (Expected Improvement) across parameter space.

- Select next experiment(s) by maximizing acquisition function.

- Execute experiments using automated platforms.

- Iterate until convergence criteria met (improvement <1% over 10 iterations).

Validation and Model Assessment

- Performance Verification

- Validate optimized conditions in triplicate at 10x scale to confirm reproducibility.

- Assess model accuracy by comparing predicted vs. actual performance for validation set.

- Document optimization trajectory and final results in electronic laboratory notebook.

Workflow Visualization

Autonomous Catalyst Discovery Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Autonomous Catalyst Discovery

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes | Storage & Handling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Precursors (Pd, Cu, Ni, Fe salts) | Catalytic centers for cross-coupling and other key transformations | Use pre-weighed aliquots in sealed vials for automated dispensing; concentration typically 50-100mM in anhydrous solvents | Store under inert atmosphere (glove box); protect from light |

| Ligand Libraries (Phosphines, diamines, N-heterocyclic carbenes) | Modulate catalyst activity, selectivity, and stability | Organize in transformation-specific screening kits; include diverse steric and electronic properties | Store at -20°C under argon; minimize freeze-thaw cycles |

| Solvent Systems (DMF, DMSO, THF, toluene, MeCN) | Reaction medium influencing solubility and reactivity | Include anhydrous grades with <50ppm water content; use molecular sieves for maintenance | Store under inert atmosphere with continuous purging systems |

| Substrate Solutions (Pharmaceutical intermediates, building blocks) | Target molecules for catalytic transformation | Formulate at standardized concentrations (typically 25-50mM) with internal standards | Store according to stability requirements; use within validated shelf life |

| Quenching Solutions (TFA, AcOH, aqueous bases) | Stop reactions at precise timepoints for accurate kinetics | Compatibility with analytical methods is critical; include precipitation agents for enzyme quenching | Store in automated dispensers with regular replacement (every 2 weeks) |

| Internal Standards (dodecane, mesitylene, deuterated analogs) | Enable quantitative analysis and normalization | Select compounds with minimal interference with analytes; use consistent concentration across experiments | Store in sealed containers; verify stability periodically |

Application Notes for Specific Pharmaceutical Contexts

Hydrogenation of Complex Drug Intermediates

Early HTE successes in homogeneous asymmetric hydrogenation demonstrated the power of automated approaches for pharmaceutical applications [14]. The protocol follows the general nanoscale screening approach (Section 3.1) with these modifications:

- Pressure Considerations: Implement specialized reactors capable of maintaining H2 pressure (1-100 atm) with continuous monitoring.

- Oxygen Sensitivity: Extend inert gas purging to 24 hours and include oxygen scavengers in glove boxes (<1ppm O2).

- Chiral Analysis: Incorporate chiral stationary phases for UPLC-MS to simultaneously determine conversion and enantiomeric excess.

Cross-Coupling for Fragment Assembly

The application of evolved HTE techniques to Pd- and Cu-catalyzed cross-coupling chemistry addressed significant challenges in pharmaceutical synthesis [14]. Key adaptations include:

- Handling Heterogeneous Systems: Implement continuous agitation to maintain suspensions of solid bases or heterogeneous catalysts.

- Gas Management: For reactions involving CO or other gases, use pressurized systems with gas concentration monitoring.

- Byproduct Analysis: Include method for detecting homocoupling and other common side products.

The historical progression from early high-throughput experimentation to modern autonomous discovery systems provides critical insights for the future of catalyst development in pharmaceutical applications. The protocols and applications detailed herein demonstrate how integration of automation, miniaturization, and artificial intelligence—particularly Bayesian optimization and emerging LLM approaches [16]—enables navigation of complex catalyst design spaces that defy traditional research methodologies. These approaches have fundamentally transformed pharmaceutical synthesis, moving from labor-intensive, sequential experimentation to parallelized, informatics-driven discovery. As autonomous systems continue to evolve, the lessons from early HTE implementation will remain essential for developing robust, reproducible, and efficient catalyst discovery platforms capable of addressing the escalating global need for sustainable chemical synthesis.

The convergence of global challenges in energy sustainability and human health demands a transformative approach to research and development. Traditional methods are often too slow to address the urgent needs in clean energy transition and drug discovery. Autonomous discovery systems, which integrate robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), and high-throughput experimentation, are emerging as a pivotal solution to accelerate innovation in both fields. These systems leverage self-driving laboratories (SDLs) and AI-driven data analysis to rapidly identify new materials and molecules, dramatically reducing the time from hypothesis to solution. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for implementing these advanced technologies, framed within the context of autonomous catalyst discovery and pharmaceutical development.

Application Notes: Sustainable Energy

The transition to a sustainable energy economy requires the rapid development of novel materials, particularly catalysts for energy conversion and storage. Autonomous discovery systems are uniquely positioned to meet this challenge.

Quantitative Landscape of U.S. Sustainable Energy, 2024

The following data illustrates the current state and growth of key sustainable energy technologies in the United States, highlighting sectors where accelerated material discovery is critical [17].

Table 1: Key U.S. Sustainable Energy Metrics and Growth Drivers (2024)

| Metric | 2024 Value or Status | Year-on-Year Change | Implication for Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power Generation Mix (Renewables) | 24% of total generation | +10.2% | Drives need for efficient electrocatalysts for H₂ production and energy storage. |

| Power Generation Mix (Natural Gas) | 42.9% of total generation | Remained stable | Highlights need for catalysts for cleaner NG combustion and carbon capture. |

| Energy Storage Additions | 11.9 GW (record) | +55% | Urgent requirement for new battery materials and catalysts for flow batteries. |

| Corporate Clean Power Purchases (PPAs) | 28 GW (record) | +26% vs. 2022 | Signals massive demand, putting pressure on supply chains and material innovation. |

| Electric Vehicle (EV) Sales | 1 in 10 new cars | +6.5% | Accelerates need for better fuel cell catalysts, battery materials, and rare-earth-free motors. |

| U.S. Energy Productivity | Record high | +2.0% | Underscores the economic benefit of energy-efficient technologies and materials. |

| U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions | +0.5% (15.8% below 2005) | Increase in Industry sector | Focuses effort on decarbonizing industrial processes (e.g., green steel, cement) via catalysis. |

Protocol: Autonomous Workflow for Heterogeneous Catalyst Discovery

This protocol outlines a closed-loop workflow for the discovery and optimization of heterogeneous catalysts, such as those for carbon dioxide reduction or hydrogen evolution.

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Discovery of Energy Catalysts

- Objective: To autonomously synthesize, test, and optimize solid-state catalyst compositions for a target energy application.

Principles: This protocol uses Bayesian optimization to guide experiments, minimizing the number of iterations needed to find a high-performing material [4].

Materials and Reagents:

- Precursor Libraries: Digital inventory of metal salts (e.g., nitrates, chlorides), ligand solutions, and solid supports (e.g., TiO₂, ZrO₂, Carbon).

- Synthesis Platform: Robotic liquid handler for precursor dispensing, automated tube furnace for calcination/annealing.

- Characterization Module: In-line Raman spectrometer or X-ray diffractometer for rapid structural analysis.

- Testing Reactor: High-throughput parallel plug-flow reactor system for catalytic performance evaluation.

- AI Controller: Computer running Bayesian optimization software (e.g., Python with

scikit-optimizeorGPyOpt).

Procedure:

- Hypothesis & Design: Define the experimental search space (e.g., elemental ratios, annealing temperature). The AI proposes an initial set of candidate compositions from a vast chemical space [18].

- Autonomous Synthesis: a. The robotic liquid handler dispenses precursor solutions onto a well-plate or into individual reactor tubes. b. The sample array is transferred to an automated furnace for drying and calcination under a programmed atmosphere.

- High-Throughput Characterization: The synthesized material library is analyzed via in-line characterization to confirm phase purity and obtain preliminary structural data.

- Performance Testing: The sample array is transferred to the testing reactor. Catalytic activity (e.g., conversion, selectivity) is measured in parallel under standardized conditions.

- Data Integration & AI Decision: Performance and characterization data are automatically fed into the AI model. The Bayesian optimization algorithm analyzes the results and proposes the next, most informative set of experiments to get closer to the performance target [4].

- Iteration: The loop (Steps 2-5) continues autonomously until a performance threshold is met or the budget is exhausted.

Workflow Visualization: Autonomous Energy Materials Discovery

Figure 1: Closed-loop workflow for autonomous catalyst discovery.

Application Notes: Pharmaceutical Development

The pharmaceutical industry is leveraging similar autonomous and AI-driven approaches to overcome rising R&D costs and stagnating productivity, focusing on prevention, personalization, and prediction [19].

Key Trends Driving Pharma R&D Innovation

Table 2: Transformative Trends and Technologies in Pharmaceutical R&D (2025)

| Trend | Key Driver | Impact on R&D | Required Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI in Drug Discovery | Machine Learning & Data Analytics | Reduces discovery time/cost; predicts molecular interactions & trial outcomes [20]. | AI platforms for target identification; digital agents for clinical trial simulation. |

| Personalized Medicine | Genomics & Molecular Biology | Shifts focus to targeted therapies for smaller patient populations, requiring more efficient trials [19] [20]. | Companion diagnostics; RWE integration; in silico trial models for patient stratification. |

| In Silico Trials | Advanced Computing & Simulation | Reduces need for animal/human trials; accelerates timelines and lowers costs [20]. | Validated computational disease models; regulatory acceptance of digital evidence. |

| Real-World Evidence (RWE) | Wearables & Health Records | Provides post-market effectiveness data; informs regulatory decisions and new indications [20]. | Data harmonization tools; NLP for analyzing unstructured EHR data. |

| Sustainability | Environmental Regulation & ESG | Drives innovation in green chemistry, energy-efficient manufacturing, and waste reduction [20]. | Life-cycle assessment software; continuous flow manufacturing systems. |

Protocol: AI-Augmented Synthesis Planning for Small Molecules

This protocol utilizes large language models (LLMs) to extract and standardize synthetic procedures from literature, facilitating the rapid planning of molecule synthesis, including pharmaceutical intermediates.

Protocol 2: Natural Language Processing for Synthesis Protocol Extraction

- Objective: To automatically convert unstructured text descriptions of chemical synthesis into a structured, machine-readable sequence of actions.

Principles: Transformer-based language models are fine-tuned on annotated corpora of scientific text to recognize chemical entities and synthesis actions [21].

Materials and Software:

- Text Corpus: Digital collection of scientific publications and patents (e.g., in PDF or HTML format).

- Annotation Software: Tool for manual annotation of action terms (e.g., BRAT, Prodigy).

- ACE Model: Fine-tuned transformer model for action sequence extraction (e.g., based on BART or T5 architectures) [21].

- Web Application: User-friendly interface for researchers to input text and receive structured output.

Procedure:

- Data Curation and Annotation: a. Compile a dataset of synthesis paragraphs from the target literature (e.g., for a specific catalyst or molecule). b. Manually annotate the text to identify and label key action terms (e.g., "mix", "heat", "stir", "filter") and their associated parameters (e.g., temperature, duration, atmosphere) [21].

- Model Fine-Tuning: a. Use the annotated dataset to fine-tune a pre-trained language model. This teaches the model the specific language of chemical synthesis. b. Validate model performance using metrics like Levenshtein similarity and BLEU score to ensure accurate translation of text to action sequences [21].

- Deployment and Extraction: a. Deploy the fine-tuned model via a web application or API. b. Input new, unstructured synthesis protocols into the tool. c. The model outputs a structured list of synthesis steps with extracted parameters, ready for database entry or direct use by an SDL.

- Standardization (Guidelines): To improve machine-readability, adopt reporting guidelines such as specifying all numerical parameters with units, using standardized action verbs, and clearly separating sequential steps [21].

Workflow Visualization: AI-Driven Pharmaceutical Research

Figure 2: AI-driven extraction and application of synthesis knowledge.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The implementation of the aforementioned protocols relies on a suite of core reagents and platforms.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Autonomous Discovery Systems

| Item / Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Optimization Software | AI algorithm that models experimental space and suggests the most informative next experiments to find an optimum [4]. | Core to the decision-making engine in self-driving labs for both energy materials and pharma. |

| Precursor Chemical Library | A comprehensive, digitized collection of high-purity starting materials (metal salts, ligands, building blocks). | Provides the physical "alphabet" for constructing new materials and molecules in high-throughput. |

| Liquid Handling Robotics | Automated systems for precise, nanoliter-to-milliliter dispensing of liquid reagents. | Enables reproducible and rapid synthesis of large sample libraries in microtiter plates or vials. |

| Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) | AI technique that grounds a Large Language Model (LLM) in a specific, private database (e.g., internal research reports) [4]. | Allows researchers to query complex datasets and propose experiments based on proprietary data. |

| Annotated Synthesis Corpora | Datasets of scientific text where chemical actions and parameters have been manually labeled. | Serves as the training data for fine-tuning domain-specific language models for synthesis extraction [21]. |

Inside the Self-Driving Lab: AI Architectures and Robotic Applications

The integration of robotic hardware and automation is fundamentally transforming scientific discovery, particularly in the fields of chemistry and pharmaceuticals. Autonomous discovery systems represent a paradigm shift, moving beyond simple task automation to create integrated workflows where artificial intelligence (AI) plans, executes, and analyzes thousands of experiments with minimal human intervention. These systems, often called self-driving labs (SDLs), combine robotics, machine learning, and advanced simulation to accelerate the pace of research dramatically [1]. This evolution is critical for tackling complex challenges such as catalyst discovery and drug development, where the experimental parameter space is vast and traditional manual approaches are prohibitively slow and resource-intensive.

The core value of these automated systems lies in their ability to operate continuously, systematically exploring experimental conditions while learning from each result to inform subsequent steps. This closed-loop operation is enabling a new era of scientific inquiry, from the rapid prototyping of new materials to the optimization of pharmaceutical formulations. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for the key robotic technologies powering this revolution, with a specific focus on their application within autonomous catalyst discovery systems and robotics research.

Robotic Hardware Modules and Their Applications

Mobile Robotic Scientists

A significant advancement beyond fixed automation is the development of mobile, "human-like" robotic scientists. These dexterous, free-roaming robots are designed to navigate standard laboratory environments and interact with a wide array of existing instrumentation, much like a human researcher. Their primary function is to automate the scientist, not just the laboratory bench, by performing tasks that require movement between different workstations [1].

Key Application in Materials Discovery: At Boston University, the MAMA BEAR self-driving lab is a prime example. This system has conducted over 25,000 experiments with minimal human oversight, leading to the discovery of a material achieving 75.2% energy absorption—the most efficient energy-absorbing material known to date. This success demonstrates the potential for mobile robots to manage long-duration, high-throughput experimental campaigns for novel material properties [4].

Experimental Protocol for Mobile Robot Integration:

- Lab Space Mapping: Digitally map the laboratory floor plan into the robot's navigation system, identifying key coordinates for instruments (e.g., weigh stations, HPLC, gloveboxes).

- Instrument Interfacing: Establish standardized communication protocols (e.g., API connections, RS-232) between the robot's control system and all target laboratory instruments.

- Task Granularity Definition: Break down complex experimental procedures (e.g., "prepare catalyst sample") into discrete, atomic actions executable by the robot (e.g., "pick up vial A," "transfer 5 mL solvent," "vortex for 30 seconds").

- Safety Protocol Implementation: Program dynamic path planning to avoid obstacles and establish safe operational zones using LiDAR and vision systems to ensure collision-free coexistence with human researchers [1] [4].

Robotic Liquid Handling Systems

Robotic Liquid Handling Devices are foundational to modern laboratory automation, providing unparalleled precision, speed, and reproducibility in liquid transfer tasks. These systems are indispensable in pharmaceuticals, biotech, and diagnostics for applications ranging from high-throughput screening to the synthesis of personalized medicine formulations [22].

Core Operational Flow: The operation of a robotic liquid handler can be distilled into a standardized workflow, as shown in the diagram below.

Detailed Protocol for Liquid Handler Calibration and Operation:

- System Initialization:

- Power on the robotic arm, pipetting head, and deck plate.

- Initialize the control software and verify connectivity with the Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS).

- Pre-run Calibration:

- Liquid-Level Detection: Activate the air displacement sensor to detect the liquid surface in source containers, minimizing tip submersion depth.

- Pipette Accuracy Check: Dispense distilled water onto a microbalance at volumes spanning the operational range (e.g., 1 µL - 1 mL). Calculate accuracy (% of target) and precision (% coefficient of variation); recalibrate if values exceed 2% and 1%, respectively.

- Protocol Execution:

- Load the predefined method file specifying source/target wells, volumes, and liquid classes.

- Mount the required tip type (filtered, conductive, etc.).

- Execute the method, with the system logging all actions and any errors for traceability.

- Post-run Maintenance:

- Discard tips into a waste container.

- Run a decontamination wash cycle with 70% ethanol or a suitable detergent.

- Park the robot in its home position [22].

Integrated Catalytic Reactor Discovery Platforms

The most advanced SDLs integrate robotic fabrication, testing, and AI-driven analysis into a single, continuous loop for discovering and optimizing functional materials and reactors.

Reac-Discovery Platform Protocol:

The Reac-Discovery platform is a digital framework for autonomous catalyst reactor discovery, combining three integrated modules [13]:

Module 1: Reactor Design (Reac-Gen)

- Objective: Digitally generate and characterize reactor geometries.

- Procedure:

- Select a base structure from a library of mathematical models (e.g., Gyroid, Schwarz).

- Define parameters:

size(spatial dimensions),level(porosity/wall thickness), andresolution(mesh fidelity). - Execute the slicing routine to compute geometric descriptors: void area, hydraulic diameter, local porosity, specific surface area, and tortuosity.

- Output a validated digital design file ready for fabrication [13].

Module 2: Reactor Fabrication (Reac-Fab)

- Objective: Manufacture the designed reactor via high-resolution 3D printing.

- Procedure:

- Receive the digital design file from

Reac-Gen. - Employ stereolithography (SLA) with a high-resolution (e.g., < 50 µm) 3D printer.

- Use a chemically resistant resin compatible with the target reaction conditions.

- Functionalize the printed structure by immobilizing the catalyst (e.g., through surface adsorption or coating with a catalytic slurry) [13].

- Receive the digital design file from

Module 3: Autonomous Evaluation (Reac-Eval)

- Objective: Autonomously test and optimize the fabricated reactors.

- Procedure:

- Install the 3D-printed reactor in a continuous-flow system.

- Define the parameter space: temperature, gas/liquid flow rates, and concentration.

- Initiate the autonomous loop:

- The AI selects a set of conditions from the parameter space.

- The robotic system sets the flows and temperature.

- Real-time monitoring (e.g., via benchtop NMR) tracks reaction conversion/yield.

- Performance data is fed to the machine learning model.

- The model updates its internal surrogate model and selects the most informative set of conditions to run next.

- Continue until a performance target is met or the experimental budget is exhausted [13].

Quantitative Data and Market Context

The adoption of robotic automation is supported by strong market growth and clear performance metrics. The following tables summarize key quantitative data relevant for researchers and professionals in the field.

Table 1: Global Robotics Market Overview and Adoption Trends (2025)

| Metric | Value | Context & Source |

|---|---|---|

| Global Robotics Market Size (2024) | $94.54 Billion | 14.7% growth from 2023 [23]. |

| Projected Market Size (2034) | >$372 Billion | Anticipated CAGR of 14.7% [23]. |

| Pharmaceutical Robots Market (2024) | ~$215 Million | Projected to reach ~$460M by 2033 (CAGR ~9%) [24]. |

| Average Industrial Robot Cost | $21,350 | As of 2024 [23]. |

| Robot Density (Global Average) | 151 robots / 10,000 employees | South Korea leads with 1,012 [23]. |

| Life Sciences Robot Order Growth | 35% Increase | Year-over-year growth in key sector [25]. |

Table 2: Documented Performance Gains from Robotic Automation

| Application Area | Performance Improvement | Context & Source |

|---|---|---|

| Production Throughput | 30-50% Increase | Compared to traditional methods [26]. |

| Product Defect Reduction | Up to 80% | Due to robotic precision [26]. |

| Process Cost Savings | 25-75% Reduction | From successful automation implementation [25]. |

| Energy Absorption Material | 75.2% Efficiency | Record achieved by MAMA BEAR SDL [4]. |

| CO₂ Cycloaddition STY | Highest Reported | Achieved by Reac-Discovery platform [13]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of the protocols above relies on a set of core materials and software solutions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Robotic Automation

| Item | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Resolution 3D Printer | Fabricates complex reactor geometries with defined pore architectures. | Stereolithography (SLA) for <50 µm features [13]. |

| Chemically Resistant Resins | Raw material for printing reactors stable under reaction conditions. | Must be validated for solvent/pH/temperature resistance [13]. |

| Periodic Open-Cell Structure (POCS) Library | Digital templates for generating superior heat/mass transfer geometries. | Includes Gyroid, Schwarz, and Schoen-G surfaces [13]. |

| Immobilized Catalyst Systems | Solid catalysts fixed within reactor structures for continuous-flow reactions. | e.g., for hydrogenation or CO₂ cycloaddition [13]. |

| Bayesian Optimization Software | AI core for autonomous experimental design and optimization. | Balances exploration and exploitation in parameter space [4] [13]. |

| Robotic Liquid Handler | Automates precise liquid transfer for high-throughput screening. | Key for assay preparation and catalyst testing [22]. |

| Collaborative Robot (Cobot) | Works alongside humans for tasks like sample prep and instrument loading. | e.g., Standard Bots' RO1 for flexible, barrier-free operation [26]. |

| Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) | Manages sample metadata, experimental data, and workflow orchestration. | Critical for data integrity and connecting hardware modules [22]. |

Application Note: Accelerating Catalyst Discovery with Active Learning and Bayesian Optimization

The development of high-performance catalysts is a complex challenge due to the vastness of the chemical and compositional space. Traditional methods, which rely on iterative, human-guided experimentation, are often slow, resource-intensive, and can miss optimal solutions. Autonomous discovery systems, which integrate robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), and advanced computational frameworks, are reimagining the future of scientific discovery by transforming this process [1] [4]. This application note details the implementation of a closed-loop, active learning strategy powered by Bayesian optimization (BO) to streamline the development of high-performance catalysts for Higher Alcohol Synthesis (HAS) and other critical reactions [27]. By leveraging AI to guide experimental workflows, researchers can achieve a dramatic reduction in the number of experiments required, significantly accelerating the pace of discovery while improving economic and environmental sustainability [27].

Core Principles and Quantitative Impact

Active learning creates a closed-loop relationship between data acquisition, machine intelligence, and physical experimentation [27]. In this framework, an AI model is used to guide the selection of subsequent experiments based on existing data. The core of this data-driven model often combines Gaussian Process (GP) models with Bayesian Optimization (BO) algorithms [27]. The GP model serves as a surrogate, predicting the performance of unexplored candidates and quantifying the uncertainty of its predictions. The BO acquisition function, such as Expected Improvement (EI) or Predictive Variance (PV), then uses this information to balance exploration (probing uncertain regions of the search space) and exploitation (focusing on areas predicted to be high-performing) [27].

The quantitative benefits of this approach are substantial, as demonstrated in recent research on FeCoCuZr catalysts for HAS [27]. The table below summarizes the key performance metrics achieved through active learning compared to traditional methods.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Active Learning in Catalyst Development

| Metric | Traditional Methods | Active Learning Approach | Improvement/Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Experiments | Hundreds to thousands [27] | 86 experiments [27] | >90% reduction in experiments [27] |

| Search Space Coverage | Limited, intuitive sampling | Systematic exploration of ~5 billion combinations [27] | Identified optimal regions in a vast space [27] |

| Higher Alcohol Productivity (STYHA) | ~0.3 gHA h⁻¹ gcat⁻¹ [27] | 1.1 gHA h⁻¹ gcat⁻¹ [27] | 5-fold improvement, highest reported for direct HAS [27] |

| Stability | Varies | Stable operation for >150 hours [27] | Confirmed long-term performance [27] |

| Multi-objective Optimization | Challenging, trade-offs poorly defined | Enabled identification of Pareto-optimal catalysts [27] | Uncovered intrinsic trade-offs between productivity and selectivity [27] |

Integrated Workflow for Autonomous Catalyst Discovery

The application of active learning and BO extends beyond a single reaction. Another powerful implementation is Multifidelity Bayesian Optimization (MF-BO), which integrates data from experiments of differing costs and accuracies (e.g., computational docking, single-point inhibition assays, and full dose-response curves) [28]. This approach mimics the traditional experimental funnel but uses AI to iteratively and optimally select which molecule to test at which fidelity level, maximizing the information gain per unit of resource spent [28]. In a prospective search for new histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACIs), an MF-BO integrated platform docked over 3,500 molecules, automatically synthesized and screened more than 120 molecules, and identified several new inhibitors with submicromolar potency, all within a constrained budget [28].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of such a closed-loop, autonomous discovery system.

Protocol: Implementation of an Active Learning Campaign for Catalyst Optimization

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for conducting an active learning campaign to optimize a multicomponent catalyst, as exemplified by the development of FeCoCuZr catalysts for higher alcohol synthesis [27]. The process is divided into distinct phases, allowing for progressive complexity from composition optimization to multi-objective analysis.

Materials and Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Role in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|