Artificial Neural Networks for Catalyst Performance: A Comprehensive Guide to Modeling, Optimization, and Validation

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) in modeling and predicting catalyst performance, a transformative approach accelerating discovery in energy and chemical sciences.

Artificial Neural Networks for Catalyst Performance: A Comprehensive Guide to Modeling, Optimization, and Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) in modeling and predicting catalyst performance, a transformative approach accelerating discovery in energy and chemical sciences. It covers the foundational paradigm shift from trial-and-error methods to data-driven discovery, detailing the specific workflow of ANN development from data acquisition to model training. The content delves into advanced methodological applications across diverse catalytic reactions, including hydrogen evolution and CO2 reduction, and addresses critical challenges such as data quality and model interpretability through troubleshooting and optimization strategies. A dedicated section on validation and comparative analysis equips researchers to evaluate model robustness and generalizability against traditional methods and other machine learning algorithms. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and development professionals, this guide synthesizes current innovations to bridge data-driven discovery with physical insight for efficient catalyst design.

The ANN Revolution in Catalysis: From Trial-and-Error to Data-Driven Discovery

The field of catalysis research is undergoing a profound transformation, shifting from traditional development modes that relied heavily on experimental trial-and-error and high-cost computational simulations toward an intelligent prediction paradigm powered by machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) [1]. This paradigm shift addresses fundamental limitations in traditional catalyst development, which has been characterized by extended cycles, high costs, and low efficiency [2] [3]. The integration of machine learning, particularly artificial neural networks (ANNs), has begun to unravel the complex, non-linear relationships between catalyst composition, electronic structure, reaction conditions, and catalytic performance [4].

The emergence of this new research paradigm aligns with broader digital transformation trends across process industries, where organizations progress through stages of digital maturity from basic data collection to advanced, data-driven decision making [5]. In catalysis research, this evolution has manifested as three distinct, progressive stages of ML integration that represent increasing levels of sophistication and capability. These stages form a comprehensive framework for understanding how machine learning, especially neural network technologies, is fundamentally reshaping catalyst performance modeling and discovery.

This application note details these three stages of ML integration in catalysis research, providing structured protocols, quantitative performance comparisons, and practical toolkits for implementation. By framing this transformation within the context of artificial neural networks for modeling catalyst performance, we aim to equip researchers with the methodological foundation needed to navigate this rapidly evolving landscape.

The Three Stages of ML Integration in Catalysis

Stage 1: Data-Driven Catalyst Screening and Performance Prediction

The initial stage of ML integration focuses on establishing data-driven approaches for catalyst screening and performance prediction, moving beyond traditional trial-and-error methods. This stage leverages supervised learning algorithms to identify hidden patterns in high-dimensional data, enabling rapid prediction of catalyst properties and activities without resource-intensive experimental or computational methods.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Catalyst Screening with ANN

Data Acquisition and Curation: Compile a standardized dataset from computational and experimental sources. Essential databases include Catalysis-Hub, Materials Project, and OQMD [6]. For COâ‚‚ hydrogenation catalysts, collect features such as adsorption energies, d-band centers, coordination numbers, and elemental properties (electronegativity, atomic radius) [4].

Feature Engineering: Transform raw data into meaningful descriptors. For alloy catalysts, calculate features like d-band center, surface energy, and work function. Apply dimensionality reduction techniques (PCA, t-SNE) to mitigate the curse of dimensionality [2] [6].

Model Architecture and Training: Implement a feedforward neural network with 2-3 hidden layers using hyperbolic tangent activation functions. For initial screening, structure the network with 50-100 neurons per hidden layer. Use a 80:20 train-test split and apply L2 regularization (λ = 0.001) to prevent overfitting [6].

Performance Validation: Evaluate model performance using k-fold cross-validation (k=5-10) and calculate standard metrics: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and coefficient of determination (R²). For catalytic performance prediction, target RMSE < 0.05 eV for adsorption energy prediction [4].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of ANN Models for Catalyst Screening

| Catalytic System | Prediction Target | Best Algorithm | MAE | RMSE | R² | Data Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu-Zn Alloys [4] | Methanol yield | ANN | 0.02 eV | 0.03 eV | 0.96 | 92 DFT |

| FeCoCuZr [7] | Alcohol productivity | Gaussian Process | 8.2% | 10.5% | 0.89 | 86 experiments |

| Single-atom Catalysts [1] | COâ‚‚ to methanol | ANN + Active Learning | 0.03 eV | 0.04 eV | 0.94 | 3000 screening |

Stage 2: Active Learning and Multi-Objective Optimization

The second integration stage employs active learning strategies to iteratively guide experimental design and optimization. This approach creates a closed-loop system between data generation and model refinement, dramatically reducing the number of experiments required to identify optimal catalysts. This stage is particularly valuable for navigating complex, multi-component catalyst systems with vast compositional spaces.

Experimental Protocol: Active Learning for Catalyst Optimization

Initial Sampling and Space Definition: Define the chemical and parameter space for exploration. For a FeCoCuZr higher alcohol synthesis catalyst system, this encompasses approximately 5 billion potential combinations of composition and reaction conditions [7]. Begin with a diverse initial dataset (10-20 samples) using Latin Hypercube Sampling to ensure broad coverage.

Acquisition Function and Model Update: Implement a Gaussian Process (GP) model as the surrogate function. Use Bayesian Optimization (BO) with an Expected Improvement acquisition function to select the most informative subsequent experiments. After each iteration (typically 4-6 experiments), update the GP model with new data [7].

Multi-Objective Optimization: For complex performance requirements, implement multi-objective optimization. For higher alcohol synthesis, simultaneously maximize alcohol productivity while minimizing COâ‚‚ and CHâ‚„ selectivity. The algorithm identifies Pareto-optimal solutions that balance these competing objectives [7].

Experimental Validation and Closure: Execute the proposed experiments from the acquisition function. Measure key performance metrics (e.g., STYâ‚•â‚ for higher alcohols) and incorporate results into the dataset. Continue iterations until performance targets are met or saturation occurs (typically 5-8 cycles) [7].

Table 2: Impact of Active Learning on Experimental Efficiency

| Catalyst System | Traditional Approach | Active Learning | Reduction in Experiments | Performance Improvement | Cost Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FeCoCuZr HAS [7] | 1000+ experiments | 86 experiments | 91.4% | 5x higher alcohol productivity | 90% |

| COâ‚‚ to Methanol SAC [1] | 3000 DFT calculations | 300 DFT + ML | 90% | Identified novel SACs | 85% |

| Surface Energy Prediction [1] | 10,000 DFT calculations | ML with active learning | 99.99% | 100,000x speedup | 95% |

Stage 3: Predictive Dynamics and Fundamental Mechanism Elucidation

The most advanced stage of ML integration focuses on predicting dynamic catalytic behavior and elucidating fundamental reaction mechanisms. This involves using neural networks to explore complex reaction pathways, transition states, and microkinetics, providing atomic-level insights that were previously computationally prohibitive. Neural network potentials (NNPs) enable accurate molecular dynamics simulations at significantly reduced computational cost compared to traditional density functional theory (DFT).

Experimental Protocol: Transition State Screening with Neural Network Potentials

Reaction Network Exploration: For the target catalytic system (e.g., Cu and Cu-Zn surfaces for COâ‚‚ hydrogenation), define the scope of possible reaction intermediates and pathways. The MMLPS (Microkinetic-guided Machine Learning Path Search) framework enables autonomous exploration without prior mechanistic assumptions [4].

Neural Network Potential Training: Train a global neural network (G-NN) potential on a diverse set of DFT calculations encompassing various adsorbate configurations and surface structures. For Cu-Zn systems, include 500-1000 DFT calculations covering key intermediates (*CO₂, *H, *O, *HCOOH, *CH₃OH) [4].

Transition State Search and Validation: Implement the CaTS (Catalyst Transition State screening) framework that combines neural network potentials with dimer method or nudged elastic band calculations for transition state search. Validate identified transition states through frequency calculations confirming a single imaginary frequency [1].

Microkinetic Modeling and Analysis: Integrate the neural network-predicted energies and transition states into a microkinetic model to determine dominant reaction pathways and rate-determining steps under realistic conditions. For COâ‚‚ hydrogenation on Cu-Zn, this revealed the formate pathway dominance and Zn decoration effects on Cu(211) step edges [4].

Table 3: Neural Network Applications in Catalytic Mechanism Studies

| Application Area | ML Framework | Traditional Method | ML Performance | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Path Search [4] | MMLPS with G-NN | DFT-based sampling | Near-DFT accuracy, 1000x faster | Zn atoms preferentially decorate Cu(211) step edges |

| Transition State Screening [1] | CaTS with transfer learning | DFT frequency calculations | 10,000x efficiency gain | Enabled screening of hundreds of catalytic systems |

| Descriptor Identification [4] | SISSO | Linear regression | Identified non-linear descriptors | Methanol yield tied to temperature and adsorption balance |

| Surface Property Prediction [1] | SurFF foundation model | DFT surface calculations | 100,000x speedup | High-throughput surface energy prediction |

The Research Toolkit: Essential Solutions for ML-Driven Catalysis

Successful implementation of artificial neural networks in catalyst performance research requires both computational tools and experimental frameworks. This section details essential research reagents and solutions that form the foundation for modern, data-driven catalysis research.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Driven Catalyst Studies

| Category | Solution/Reagent | Specifications | Research Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Databases | CatalysisHub [6] | Reaction energies, activation barriers | Training data for activity prediction | Screening adsorption properties |

| Feature Generation | d-band center calculator [6] | Electronic structure descriptor | Predicts adsorption strength | Metal alloy catalyst design |

| ML Algorithms | ANN with Bayesian optimization [7] | Python (scikit-learn, PyTorch) | Non-linear pattern recognition | Complex composition-performance relationships |

| Active Learning Platform | Gaussian Process Regression [7] | Uncertainty quantification | Guides iterative experimentation | FeCoCuZr catalyst optimization |

| Reaction Analysis | CaTS framework [1] | Transition state screening | Accelerates kinetic analysis | Identifies rate-determining steps |

| Performance Validation | High-throughput reactor [7] | Parallel testing capability | Experimental validation of predictions | Confirm ML-predicted optimal catalysts |

| 1,3-Dibromo-1,3-dichloroacetone | 1,3-Dibromo-1,3-dichloroacetone|CAS 62874-84-4 | 1,3-Dibromo-1,3-dichloroacetone is a halogenated disinfection byproduct (DBP) for research. This product is for Research Use Only. Not for human or personal use. | Bench Chemicals | |

| 6-Hydroxy-7-methoxydihydroligustilide | 6-Hydroxy-7-methoxydihydroligustilide|High-Purity | 6-Hydroxy-7-methoxydihydroligustilide is a high-purity phthalide for research on neurodegeneration and vascular function. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

The integration of machine learning in catalysis research has evolved through three distinct stages—from initial data-driven screening to active learning optimization and finally to predictive dynamics and mechanism elucidation. This progression represents a fundamental paradigm shift from traditional trial-and-error approaches to rational, AI-guided catalyst design. Artificial neural networks have proven particularly valuable in modeling the complex, non-linear relationships inherent in catalyst performance, enabling researchers to navigate vast chemical spaces with unprecedented efficiency.

As these methodologies continue to mature, the catalysis research landscape is transforming into a more integrated, data-driven discipline. Future developments will likely focus on strengthening the connections between these three stages, creating seamless workflows from initial screening to mechanistic understanding. The researchers and organizations who successfully master and integrate these three stages of ML adoption will be positioned at the forefront of catalytic science, capable of addressing critical challenges in energy sustainability and chemical production with accelerated, intelligent design capabilities.

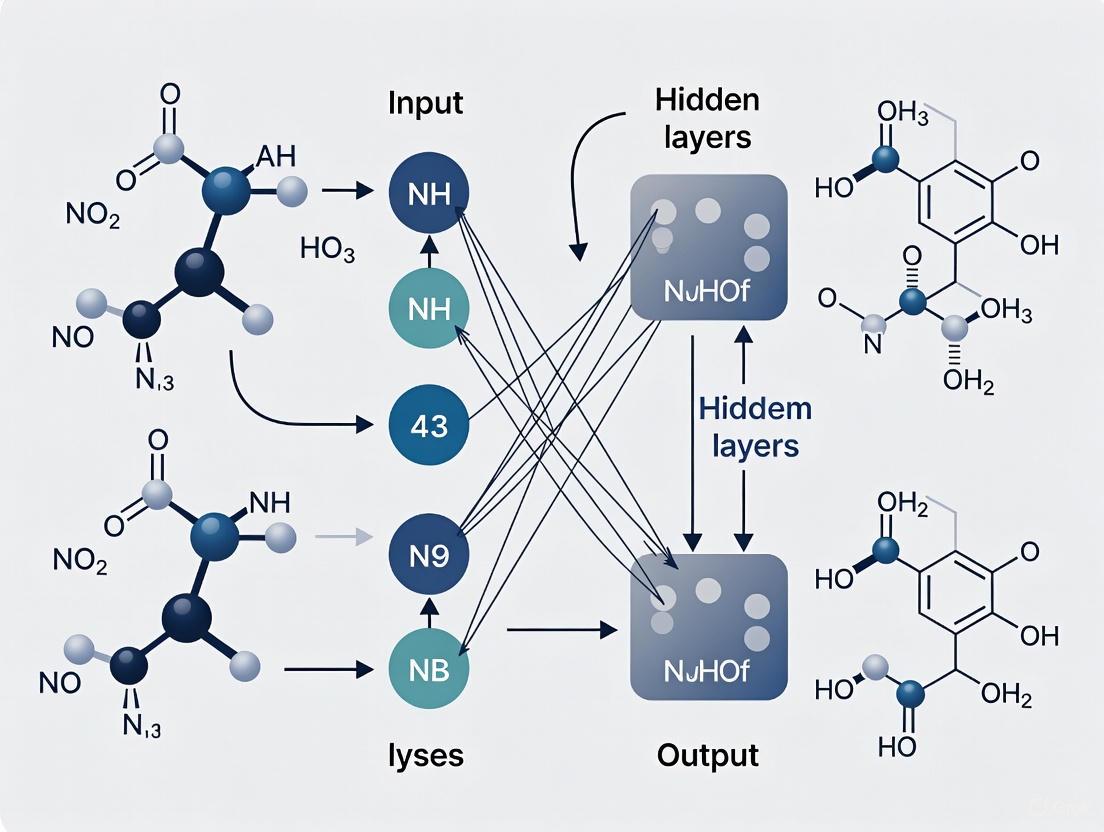

A Feedforward Neural Network (FNN) is the most fundamental architecture in deep learning, characterized by its unidirectional information flow. In an FNN, connections between nodes do not form cycles, meaning information moves exclusively from the input layer, through potential hidden layers, to the output layer in a single direction. This structure is formally known as a directed acyclic graph [8].

This one-way flow distinguishes FNNs from more complex architectures like recurrent neural networks (RNNs), which can have feedback loops, creating an internal memory. The simplicity of FNNs makes them more straightforward to train and analyze, providing an essential foundation for understanding broader neural network concepts [8]. They serve as powerful, universal function approximators, capable of mapping complex, non-linear relationships between inputs and outputs, which is highly valuable for predictive modeling in scientific research.

Core Architectural Principles

The architecture of a feedforward neural network is built upon several key components and principles that work in concert to transform input data into a predictive output.

Fundamental Components

- Input Layer: The network's entry point, which receives the feature data. Each node (or neuron) in this layer represents a single feature.

- Hidden Layers: These intermediate layers sit between the input and output layers. Each neuron in a hidden layer performs a weighted sum of its inputs, adds a bias, and passes the result through a non-linear activation function. Deep networks contain multiple hidden layers.

- Output Layer: The final layer that produces the network's prediction. The nature of its activation function (e.g., linear, softmax) depends on the task (regression or classification).

- Connections: Every connection between neurons has an associated weight (

W). During training, these weights are adjusted to minimize prediction error [9].

The Mathematical Engine of a Single Neuron

The operation of a single neuron can be mathematically represented as:

Y = f ( Σ (Wn • Xn) ) [9]

Where:

- Y is the neuron's output.

- f is the non-linear activation function.

- Wn is the weight associated with the n-th input connection.

- Xn is the n-th input value.

The summation (Σ) is the weighted sum of all inputs plus a bias term. This calculation is fundamental to the network's ability to learn complex patterns.

Advanced Concepts and Theoretical Limits

Memory Capacity in Single-Layer FNNs

For binary single-layer FNNs, the theoretical maximum memory capacity—the number of patterns (P) that can be stored and perfectly recalled—is not infinite. It is governed by the network's size and the sparsity of the data [10].

Table 1: Factors Influencing Neural Network Storage Capacity

| Factor | Symbol | Description | Impact on Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Size | N |

Number of input/output units. | Increases exponentially as (N/S)^S where S is sparsity [10]. |

| Pattern Sparsity | S |

Number of active elements in each input pattern. | Higher sparsity (fewer active units) generally increases capacity [10]. |

| Pattern Differentiability | D |

Minimum Hamming distance between any two stored patterns. | Higher differentiability (more orthogonal patterns) reduces interference but limits the pool of candidate patterns [10]. |

Exceeding this capacity leads to catastrophic forgetting, where learning new patterns interferes with or erases previously learned ones. This is a significant challenge in continual learning scenarios [10].

The Tabular Foundation Model (TabPFN)

A recent innovation demonstrating the evolving application of FNN principles is the Tabular Prior-data Fitted Network (TabPFN). TabPFN is a transformer-based foundation model designed for small-to-medium-sized tabular datasets. It leverages in-context learning (ICL), the same mechanism powering large language models, to perform Bayesian inference in a single forward pass [11].

- Methodology: TabPFN is pre-trained on millions of synthetic tabular datasets generated from a defined prior distribution. When presented with a new dataset, it uses the training samples as context to directly predict the labels of test samples without traditional iterative training [11].

- Significance: This approach can outperform gradient-boosted decision trees on datasets with up to 10,000 samples, and does so thousands of times faster, showcasing the potential for rapid, accurate analysis common in scientific research [11].

Experimental Protocols for FNN Application

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for developing a predictive model using a Feedforward Neural Network, adaptable for tasks like modeling catalyst performance.

Protocol 1: Building a Predictive FNN Model

Objective: To construct and train an FNN for predicting material properties or catalytic performance based on process parameters.

Workflow Overview: The diagram below illustrates the end-to-end workflow for this protocol.

Materials and Reagents:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

| Item | Type | Function/Description |

|---|---|---|

| Process Parameter Dataset | Data | Input features (e.g., temperature, pressure, precursor concentrations). Serves as the model's input (X) [9]. |

| Performance Metric Data | Data | Target output (y) for supervised learning (e.g., yield strength, catalytic activity, conversion efficiency) [9]. |

| Python with PyTorch/TensorFlow | Software | Core programming environment and libraries for building, training, and evaluating neural network models. |

| Scikit-learn | Software | Provides essential utilities for data preprocessing (e.g., StandardScaler), model evaluation, and train-test splitting. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) or GPU | Hardware | Accelerates the computationally intensive model training process. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Preparation and Feature Selection

- Collect Data: Assemble a dataset where each row represents an experiment and columns represent input parameters and the corresponding target output(s). For example, a catalyst study might use inputs like

feed speed ratio,temperature, andprecursor concentration, with an output likereaction yield[9]. - Preprocess Data: Clean the data by handling missing values and outliers. Normalize or standardize the input features to a common scale (e.g., using

StandardScalerfrom Scikit-learn) to ensure stable and efficient training. - Split Dataset: Partition the data into three sets: Training Set (~70%) for model learning, Validation Set (~15%) for hyperparameter tuning, and Test Set (~15%) for final, unbiased evaluation.

- Collect Data: Assemble a dataset where each row represents an experiment and columns represent input parameters and the corresponding target output(s). For example, a catalyst study might use inputs like

Model Architecture Design

- Define Layers: Specify the number of hidden layers (depth) and the number of neurons in each layer (width). Start with a simple architecture (e.g., 1-2 hidden layers) and increase complexity if necessary.

- Select Activation Functions: Choose non-linear activation functions for the hidden layers (e.g., ReLU - Rectified Linear Unit) to enable the network to learn complex patterns. The output layer's activation function should match the task: a linear function for regression or sigmoid/softmax for classification.

- Initialize Model: Create the FNN model in your chosen framework (e.g., PyTorch or TensorFlow).

Model Training and Validation

- Choose Loss Function and Optimizer: Select a loss function appropriate for the task (e.g., Mean Squared Error (MSE) for regression). Choose an optimizer like Adam or SGD (Stochastic Gradient Descent) to update the network weights.

- Train the Model: Iteratively present batches of training data to the model. The optimizer adjusts the weights to minimize the loss between the model's predictions and the true target values.

- Validate and Tune: After each training epoch (a full pass through the training data), use the validation set to monitor performance and prevent overfitting. Use these results to tune hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate, number of layers/neurons, batch size).

Model Evaluation and Inference

- Final Testing: Evaluate the final, tuned model on the held-out test set to obtain an unbiased estimate of its performance on new, unseen data.

- Deploy for Prediction: Use the trained model to predict outcomes for new experimental conditions, aiding in catalyst design and optimization.

Application Notes in Scientific Research

FNNs have proven to be versatile and effective tools across diverse scientific domains. The following case studies highlight their practical utility.

Table 3: Case Studies of FNNs in Scientific Modeling

| Field | Study Objective | FNN Architecture & Performance | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Engineering [9] | Predict mechanical properties (Yield Strength, UTS, Elongation) of flow-formed AA6082 tubes. | FNN vs. Elman RNN vs. Multivariate Regression. FNN achieved the lowest avg. prediction error of 7.45%. | FNNs can effectively model complex, non-linear relationships in manufacturing processes, outperforming both traditional regression and certain recurrent architectures for this static prediction task [9]. |

| Epidemiology [12] | Predict the 2025 measles outbreak case numbers in the USA. | A simple FNN using historical data features. Achieved a Mean Squared Error (MSE) of 1.1060 over 34 weeks of testing. | Relatively simple FNN architectures can provide accurate, real-time predictions for public health crises, offering a valuable tool for resource planning and intervention strategies [12]. |

| Computer Science [13] | Investigate the emergence of color categorization in a neural network trained for object recognition. | A CNN (a specialized FNN for images) was probed for its internal representation of color. | Higher-level categorical representations can emerge in FNNs as a side effect of being trained on a core visual task (object recognition), suggesting that task utility can shape internal feature organization [13]. |

Visualization of a Basic Feedforward Network

The following diagram depicts the core architecture of a simple Feedforward Neural Network, showing the connections and data flow between its layers.

Application Notes

The development of high-performance catalysts is pivotal for advancing energy and chemical technologies. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) have emerged as a powerful machine learning technique to navigate the complex, high-dimensional challenges of optimizing heterogeneous catalysts, significantly accelerating the discovery process [14] [15]. ANNs are particularly valuable for establishing non-linear relationships between a catalyst's properties—such as its geometric and electronic structure—and its performance metrics, enabling predictive modeling that can guide experimental efforts [15]. This document outlines a standardized workflow for employing ANNs in catalyst performance modeling, ensuring robust, reproducible, and reliable outcomes.

The standardized workflow for ANN-based catalyst research is a sequential, iterative process. It begins with the acquisition and rigorous cleaning of data from both experimental and theoretical sources. This high-quality data is then prepared for model ingestion, followed by the careful design and training of the ANN architecture. The model is thoroughly evaluated using relevant metrics, and the insights generated are effectively visualized to guide catalyst design and optimization, potentially closing the loop by informing new data acquisition campaigns.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Data Acquisition and Cleaning for Catalytic Properties

Objective

To gather a consistent, high-quality dataset on catalyst properties and performance, and to preprocess this data to mitigate the negative effects of data contamination on ANN model training.

Materials and Reagents

- Data Sources: High-throughput experimental setups, computational databases (e.g., from Density Functional Theory calculations), and scientific literature [14] [15].

- Computing Software: Python environment with libraries such as Pandas for data manipulation, NumPy for numerical operations, and Scikit-learn for basic outlier detection.

- Specialized Tools: Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for advanced data cleaning involving relational data structures [16].

Methodology

Data Collection:

- Compile a dataset of catalyst properties. A typical dataset, as used in modern studies, may include ~235 unique heterogeneous catalysts [14].

- For each catalyst, record key performance metrics (e.g., adsorption energies for C, O, N, H) and electronic structure descriptors (e.g., d-band center, d-band filling, d-band width, d-band upper edge relative to the Fermi level) [14].

- Ensure the data range for each variable is sufficiently wide to enable the ANN to learn generalizable patterns [15].

Data Cleaning:

- Anomaly Detection: Identify and address anomalous data originating from sensor drifts or signal transmission issues. Techniques include calculating statistical metrics like the Thompson tau-local outlier factor or using a group anomaly detector that incorporates data graph structure and local density [16].

- Label Verification: Correct mislabeled data, a common issue due to expert error or environmental noise. Employ a graph clustering model (e.g., GNNs) to rectify mislabels by leveraging the underlying graph structure of the data, which is less susceptible to initial label noise [16].

- Standardization: Handle missing values by removal or imputation (e.g., filling with mean values or NAN) and check for consistency in formats and units across all variables [17].

Protocol 2: Data Preparation and Feature Selection

Objective

To transform the cleaned data into a format suitable for ANN training and to identify the most salient features for predicting catalytic performance.

Materials and Reagents

- Software: Python with Scikit-learn for data transformation and decomposition.

- Analysis Tools: Libraries for statistical analysis (e.g., SciPy) and feature importance calculation (e.g., SHAP).

Methodology

- Data Splitting: Partition the dataset into three subsets: Training (~60-70%), Validation (~15-20%), and Test (~15-20%). This separation is crucial for unbiased model evaluation and preventing overfitting [17].

- Data Transformation: Normalize or scale input features to a similar range (e.g., [0, 1] or [-1, 1]) to stabilize and accelerate the ANN training process [17].

- Feature Selection & Analysis:

- Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce dimensionality and identify dominant patterns in the electronic structure features [14].

- Use feature importance analysis, such as Random Forest or SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), to identify critical descriptors. For instance, d-band filling may be critical for predicting the adsorption energies of C, O, and N, while the d-band center is more important for H adsorption [14].

Protocol 3: ANN Model Architecture Design and Training

Objective

To construct and train an ANN model that accurately maps catalyst descriptors to performance metrics.

Materials and Reagents

- Deep Learning Frameworks: TensorFlow/Keras or PyTorch.

- Computing Hardware: Computers with GPUs for accelerated training.

Methodology

Architecture Selection:

- Design a network with input, hidden, and output layers. The input and output layers correspond to the number of features and target variables, respectively.

- Determine the number of hidden layers and neurons through iterative testing. A common starting point is a single hidden layer, with the number of neurons potentially determined by a sensitivity test to avoid under-fitting or over-fitting [15].

- Use non-linear activation functions (e.g., sigmoid, ReLU) in the hidden layers to enable the network to learn complex patterns [15].

Model Training:

- Compilation: Choose an optimizer (e.g., Adam, SGD), a loss function (e.g., Mean Squared Error for regression, Cross-Entropy for classification), and evaluation metrics (e.g., accuracy) [17].

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Optimize key parameters using the validation set.

- Fitting: Train the model on the training set and monitor its performance on the validation set to implement early stopping and prevent overfitting [17].

- Checkpointing: Save the model at intervals to retain the best-performing version [17].

Protocol 4: Model Evaluation and Interpretation

Objective

To assess the trained ANN model's predictive performance on unseen data and to interpret the model to gain physical insights into catalytic behavior.

Materials and Reagents

- Evaluation Metrics: Standard statistical measures (e.g., RMSE, R², Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score).

- Interpretation Tools: SHAP, LIME, or built-in feature importance methods.

Methodology

- Performance Validation: Use the held-out test set to generate final, unbiased performance metrics. Calculate the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) or other relevant scores to quantify prediction accuracy [15].

- Error Analysis: Examine where the model makes mistakes to identify potential areas for improvement in data quality or feature engineering [17].

- Model Interpretation: Apply techniques like SHAP analysis to understand the contribution of each input descriptor (e.g., d-band properties) to the model's predictions, transforming the "black box" model into a source of fundamental insight for catalyst design [14].

Data Presentation

Key Electronic Structure Descriptors for Catalytic Adsorption Energies

Table 1: Key electronic structure descriptors and their relative importance for predicting the adsorption energies of various atoms on heterogeneous catalysts, as identified through SHAP analysis [14].

| Descriptor | Description | Primary Influence on Adsorption Energy |

|---|---|---|

| d-band filling | The extent to which the d-electron band is occupied. | Critical for C, O, and N adsorption energies. |

| d-band center | The average energy of the d-electron states relative to the Fermi level. | Most important for H adsorption energy. |

| d-band width | The energy breadth of the d-electron band. | Secondary influence on all adsorption energies. |

| d-band upper edge | The position of the upper edge of the d-band. | Secondary influence on all adsorption energies. |

Standard Evaluation Metrics for ANN Models in Catalysis Research

Table 2: Common metrics used for evaluating the performance of regression and classification ANN models in catalysis research [17] [15].

| Metric | Formula | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | (\sqrt{\frac{\sum{i=1}^{n}(Pi - A_i)^2}{n}}) | Regression tasks (e.g., predicting adsorption energy, reaction yield). |

| Accuracy | (\frac{\text{Number of Correct Predictions}}{\text{Total Predictions}}) | Classification tasks (e.g., identifying high/low activity catalysts). |

| Precision | (\frac{\text{True Positives}}{\text{True Positives + False Positives}}) | Classification tasks where false positives are critical. |

| Recall | (\frac{\text{True Positives}}{\text{True Positives + False Negatives}}) | Classification tasks where false negatives are critical. |

| F1-Score | (2 \times \frac{\text{Precision} \times \text{Recall}}{\text{Precision} + \text{Recall}}) | Overall measure for binary classification models. |

Mandatory Visualization

ANN Catalyst Modeling Workflow

ANN Model Development & Training Process

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential computational tools and data sources for building ANN models in catalyst performance research.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Calculations | Data Source | Provides high-fidelity data on electronic structure descriptors (d-band properties) and reaction energies [14]. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation | Data Source | Generates large-scale, consistent experimental data on catalyst activity and selectivity under various conditions [14]. |

| Python (Pandas/NumPy) | Software | Core environment for data manipulation, cleaning, and numerical computations [17]. |

| TensorFlow/PyTorch | Software | Deep learning frameworks used for building, training, and deploying flexible ANN architectures [17]. |

| SHAP Analysis | Software | Provides post-hoc model interpretability, identifying the most critical catalyst descriptors for a given prediction [14]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Software/Method | Advanced method for data cleaning and modeling complex relationships in non-Euclidean data, such as material graphs [16]. |

| 2-Bromobenzoic acid-d4 | 2-Bromobenzoic acid-d4, MF:C7H5BrO2, MW:205.04 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 8-Hydroxy-ar-turmerone | 8-Hydroxy-ar-turmerone, MF:C15H20O2, MW:232.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Application Note: High-Throughput Screening of Catalytic Materials

The integration of Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) with high-throughput screening (HTS) methodologies has revolutionized the discovery and optimization of catalytic materials. This paradigm shift moves research beyond traditional "trial-and-error" approaches, enabling the rapid computational assessment of vast material libraries to identify promising candidates for experimental validation [18]. This application note details the implementation of ANN-driven HTS for catalytic materials, such as Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) for gas separation and catalytic electrodes for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER) [18] [19].

Key Quantitative Findings

Table 1: Performance Metrics of ANN Models in High-Throughput Screening Studies

| Catalytic System | Machine Learning Model | Key Performance Metric | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOF Mixed-Matrix Membranes (He/CHâ‚„ Separation) | eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) | Predictive Accuracy for MMMs Performance | Best among 4 tested models | [18] |

| CI Engine with Biofuel Blend | Levenberg-Marquardt Back-Propagation ANN | Regression Coefficient (R²) for BTE | 0.99859 | [20] |

| CI Engine with Biofuel Blend | Levenberg-Marquardt Back-Propagation ANN | Regression Coefficient (R²) for BSFC | 0.99814 | [20] |

| CI Engine with Biofuel Blend | Levenberg-Marquardt Back-Propagation ANN | Regression Coefficient (R²) for NOx | 0.92505 | [20] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Computational Screening of MOF Mixed-Matrix Membranes

This protocol describes the creation of a large-scale dataset for machine learning by integrating high-throughput computer simulations (HTCS) with polymer data, as applied to helium separation [18].

- Database Curation: Source a database of experimentally synthesized porous materials. For example, use the CoRE MOF 2019 database, which contains 10,143 MOF structures [18].

- Material Characterization via Simulation: For each MOF structure, calculate key structural and performance characteristics using molecular simulations:

- Structural Descriptors: Calculate geometric properties using tools like Zeo++, which include:

- Largest Cavity Diameter (LCD)

- Pore Limiting Diameter (PLD)

- Density (Ï)

- Accessible Surface Area (VSA)

- Accessible Pore Volume (Vp)

- Porosity (ɸ)

- Performance Metrics: Use Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) and Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to calculate:

- Gas Permeability

- Gas Selectivity (e.g., He/CHâ‚„ selectivity)

- Structural Descriptors: Calculate geometric properties using tools like Zeo++, which include:

- Polymer Data Collection: Compile a set of polymer properties from experimental literature, including gas permeability and selectivity.

- Dataset Generation for MMMs: Combine the MOF and polymer data to create a large virtual library of Mixed-Matrix Membranes (MMMs). The Maxwell model is a suitable theoretical framework for predicting the overall gas permeability of the composite membrane based on the properties of its polymer matrix and MOF fillers [18]. This process can generate a dataset of over 450,000 MMM samples [18].

- Machine Learning Model Development:

- Input Features: Use the calculated MOF descriptors, polymer properties, and MOF loading fraction as input features for the model.

- Model Training & Selection: Train multiple machine learning models (e.g., XGBoost, Random Forest, DNN) on the dataset. Evaluate their performance using metrics like Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and R² to select the best-performing model (e.g., XGBoost) [18].

- Validation: Validate the computational strategy by comparing the simulated gas permeability of known MOFs with existing experimental data to ensure accuracy [18].

Application Note: Uncovering Structure-Performance Relationships

A critical advantage of advanced machine learning models, particularly Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), is their ability to decode complex Structure-Performance Relationships in catalysis. These models can predict catalytic properties and provide human-interpretable insights into which structural features of a catalyst lead to high performance, thereby guiding rational design [21].

Key Quantitative Findings

Table 2: Capabilities of ANN/GNN Models in Elucidating Structure-Performance Relationships

| Model / System | Catalytic Reaction | Key Predictive Capability | Interpretability Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCat-GNet [21] | Rh-catalyzed Asymmetric 1,4-Addition | Predicts enantioselectivity (ΔΔG‡) and absolute stereochemistry | Identifies atoms/fragments in ligand affecting selectivity |

| HCat-GNet [21] | Asymmetric Dearomatization; N,S-Acetal Formation | Generalizability across different reaction types | Highlights key steric/electronic motifs |

| ANN [20] | CI Engine Performance and Emissions | Regression R² > 0.92 for NOx, Smoke, BTE, BSFC | "Black-box" prediction of performance from operational inputs |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Protocol 2: Predicting Enantioselectivity with a Graph Neural Network (HCat-GNet)

This protocol uses the Homogeneous Catalyst Graph Neural Network (HCat-GNet) to predict the enantioselectivity of asymmetric reactions catalyzed by metal-chiral ligand complexes, using only the SMILES representations of the molecules involved [21].

- Data Preparation and Molecular Representation:

- Input Data: Compile a dataset of catalytic reactions, including the SMILES strings of the substrate, reagent, and chiral ligand, along with the experimentally measured enantioselectivity (e.g., as ΔΔG‡ or ee).

- Graph Construction: For each molecule (ligand, substrate, reagent), automatically generate a graph representation where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges.

- Node Feature Encoding: For each atom (node), encode its chemical properties into a feature vector. This includes:

- Atomic identity (element)

- Degree (number of connected non-hydrogen atoms)

- Hybridization

- Membership in an aromatic system

- Membership in a ring

- Absolute configuration (R, S, or none) of stereocenters

- Model Training and Interpretation:

- Graph Assembly: Concatenate the individual molecular graphs into a single, disconnected reaction graph.

- Model Training: Train the GNN on the assembled reaction graphs to predict the enantioselectivity value.

- Explainability Analysis: Apply explainable AI (XAI) techniques, such as atom-based attention mechanisms, to the trained model. This analysis identifies which specific atoms within the chiral ligand the model deems most critical for achieving high or low enantioselectivity. This provides a data-driven, human-interpretable guide for ligand optimization [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ANN-Driven Catalysis Research

| Item / Solution | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CoRE MOF Database | A curated database of experimentally synthesized Metal-Organic Frameworks, providing atomic-level structures for simulation and ML. | Source of material structures for high-throughput screening of adsorbents and catalysts [18]. |

| Zeo++ Software | An algorithm for high-throughput analysis of porous materials; calculates geometric descriptors like PLD, LCD, and surface area. | Generating key input features for ML models predicting adsorption and catalytic performance [18]. |

| Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) | A molecular simulation technique used to study adsorption and separation equilibria in porous materials at a fixed chemical potential. | Calculating gas uptake and selectivity for MOFs in the dataset [18]. |

| SMILES Representation | A line notation system for representing molecular structures using short ASCII strings. | Serves as a simple, universal input for GNNs to build molecular graphs without complex DFT calculations [21]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | A class of deep learning models designed to perform inference on data described by graphs. | Mapping the complex relationship between molecular structure of catalysts and their performance (e.g., enantioselectivity) [21]. |

| Explainable AI (XAI) Techniques | Methods that help interpret the predictions of complex "black-box" models like ANNs and GNNs. | Identifying which substituents on a chiral ligand most influence enantioselectivity in asymmetric catalysis [21]. |

| 7,15-Dihydroxypodocarp-8(14)-en-13-one | 7,15-Dihydroxypodocarp-8(14)-en-13-one, MF:C17H26O3, MW:278.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Neutrophil elastase inhibitor 6 | Neutrophil elastase inhibitor 6, MF:C38H48N3O12PS3, MW:866.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Building and Applying ANN Models: From Hydrogen Evolution to CO2 Reduction

The application of artificial neural networks (ANNs) in catalyst performance research represents a paradigm shift from traditional trial-and-error experimentation to a data-driven discovery process. A critical factor determining the success of these models is input feature engineering – the strategic selection and construction of numerical descriptors that effectively capture the underlying physical and chemical properties governing catalytic behavior. This protocol provides a comprehensive framework for identifying, evaluating, and implementing key descriptors derived from electronic structure and geometric characteristics, enabling researchers to build more accurate, generalizable, and interpretable neural network models for catalyst design.

A Framework for Catalyst Descriptors

Descriptors for catalytic systems can be systematically categorized into three primary classes based on their origin and computational requirements. The table below outlines these categories, their bases, and key examples.

Table 1: Categories of Foundational Descriptors for Catalysis

| Descriptor Category | Basis | Key Examples | Typical Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic Statistical [22] | Fundamental elemental properties | Elemental composition, atomic number, valence orbital information, ionic characteristics, ionization energy [22] | Low (readily available from databases) |

| Electronic Structure [22] | Quantum mechanical calculations | d-band center ($\epsilond$) [22], spin magnetic moment [22], orbital occupancies, charge distribution, non-bonding electron count (e.g., $Ni{e-d}$) [23] | High (requires DFT calculations) |

| Geometric/Microenvironmental [24] [22] | Local atomic arrangement and structure | Interatomic distances [22], coordination numbers [22], local strain [22], surface-layer site index [22], area of metal-adsorbate triangles (e.g., $S_{M-O-O}$) [22] | Medium to High (may require structural optimization) |

Electronic Structure Descriptors

Core Concepts and Physical Basis

Electronic structure descriptors encode information about the electron density distribution and energy levels of a catalyst, which directly influence its ability to bind reaction intermediates and lower activation barriers. These descriptors are typically derived from Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations, which serve as the computational foundation for modern quantum mechanical modeling [23]. The accuracy of neural network predictions for complex properties, such as Hamiltonian matrices, is significantly enhanced when the model architecture respects fundamental physical symmetries, such as E(3)-equivariance, ensuring predictions are invariant to translation, rotation, and reflection [25] [26].

Key Electronic Descriptors and Measurement Protocols

Table 2: Key Electronic Structure Descriptors and Measurement Methods

| Descriptor | Physical Significance | Measurement Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| d-Band Center ($\epsilon_d$) [22] | Average energy of the d-band electronic states relative to the Fermi level; correlates with adsorption strength. | 1. Perform DFT calculation on the catalyst surface. 2. Project the electronic density of states (DOS) onto the d-orbitals of the metal site. 3. Calculate the first moment (weighted average energy) of the d-band DOS. |

| Spin Magnetic Moment [22] [27] | Measure of unpaired electron spin; influences reaction pathways in radical intermediates. | 1. Conduct a spin-polarized DFT calculation. 2. Integrate the spin density ($\rho{\uparrow} - \rho{\downarrow}$) over the atomic basin of interest. |

| Machine-Learned Hamiltonian [25] [26] | Full quantum mechanical Hamiltonian predicting system energy; provides a complete electronic description. | 1. Use a deep E(3)-equivariant neural network (e.g., NextHAM [25], DeepH-hybrid [26]). 2. Train on a dataset of DFT-calculated Hamiltonians. 3. The model outputs Hamiltonian matrix elements for new structures. |

| Non-Bonding Lone-Pair Electron Count ($Ni_{e-d}$) [23] | Count of non-bonding electrons in specific orbitals; can be used to predict activity trends. | 1. Perform DFT calculation to obtain electron density and orbital projections. 2. Analyze the orbital-projected DOS to identify and count non-bonding states near the Fermi level. |

Geometric and Microenvironmental Descriptors

Core Concepts and Physical Basis

Geometric descriptors quantify the spatial arrangement of atoms around an active site. The local geometry directly affects the steric accessibility for adsorbates and can induce strain that modifies electronic properties. For nanostructured catalysts like nanoparticles and high-entropy alloys, which possess diverse surface facets and binding sites, Adsorption Energy Distributions (AEDs) have been introduced as a powerful descriptor. AEDs aggregate the spectrum of adsorption energies across various facets and sites, providing a more holistic fingerprint of a catalyst's activity than a single energy value from one ideal surface [24].

Key Geometric Descriptors and Measurement Protocols

Table 3: Key Geometric and Microenvironmental Descriptors and Measurement Methods

| Descriptor | Physical Significance | Measurement Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Interatomic Distance [22] | Determines steric effects and metal-metal interactions in multi-site catalysts. | 1. Optimize the catalyst structure using DFT or a Machine-Learned Force Field (MLFF). 2. Calculate the Cartesian distance between specific atomic pairs. |

| Coordination Number [22] | Number of nearest neighbors; a lower number often indicates an under-coordinated, more reactive site. | 1. From an optimized structure, identify all atoms within a cutoff radius (e.g., the first minimum in the radial distribution function) of the central atom. 2. Count these neighbors. |

| Local Strain [22] [27] | Measure of lattice distortion from an ideal structure; strain can shift electronic energy levels. | 1. Define a reference bond length or lattice parameter ($a0$). 2. Measure the actual bond length in the system ($a$). 3. Calculate strain as $\epsilon = (a - a0)/a_0$. |

| Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED) [24] | Characterizes the range of adsorption energies available on a realistic nanoparticle catalyst. | 1. Generate a diverse set of surface slabs representing different facets and terminations. 2. For each slab, create multiple adsorption sites. 3. Use MLFFs (e.g., from OCP [24]) to compute adsorption energies for all configurations. 4. Plot the histogram of energies to form the AED. |

Integrated Workflow for Descriptor Selection and Model Implementation

The process of building a robust ANN model for catalysis involves a structured workflow from initial data collection to final model deployment. The following diagram and protocol outline this integrated approach.

Figure 1: A workflow for descriptor-driven catalyst design, integrating computational and machine learning steps.

Protocol: End-to-End Descriptor Engineering and ANN Training

Objective: To systematically select and apply electronic and geometric descriptors for training an ANN that predicts catalyst performance. Primary Applications: High-throughput screening of catalyst libraries, prediction of adsorption energies, and discovery of structure-property relationships.

Materials and Reagents:

- Computational Software: DFT code (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO), MLFF platform (e.g., Open Catalyst Project (OCP) [24]), atomistic visualization tool (e.g., OVITO, VESTA).

- Data Resources: Materials Project database [24], Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) [23], other curated DFT datasets.

- Computing Hardware: High-performance computing (HPC) cluster with CPUs/GPUs.

Procedure:

Data Acquisition and Curation: a. Define Search Space: Select metallic elements and their stable phases from databases like the Materials Project, filtered by experimental relevance and computational feasibility [24]. b. Generate Ground Truth Data: Perform high-quality DFT calculations to obtain target properties (e.g., adsorption energies, formation energies, reaction overpotentials) for a subset of materials. For geometric descriptors, use DFT or pre-trained MLFFs to relax and optimize catalyst structures [24]. c. Data Cleaning: Validate computational results and remove outliers. Benchmark MLFF-predicted energies against explicit DFT calculations to ensure accuracy (e.g., target MAE < 0.2 eV for adsorption energies) [24].

Descriptor Calculation and Selection: a. Compute Foundational Descriptors: Calculate a broad initial set of descriptors from all three categories (Intrinsic, Electronic, Geometric). b. Feature Engineering: Construct composite descriptors if necessary. For example, the ARSC descriptor integrates Atomic property, Reactant, Synergistic, and Coordination effects into a single, powerful feature [22]. c. Feature Selection: Apply techniques like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) or feature importance analysis from tree-based models (e.g., XGBoost) to identify the most predictive descriptors and reduce dimensionality [22]. The goal is a compact, non-redundant, and physically meaningful descriptor set.

Model Training and Validation: a. Algorithm Selection: Choose an ANN architecture suitable for the data. For complex, geometric input, use E(3)-equivariant graph neural networks [25] [26]. For tabular descriptor data, fully connected networks or tree ensembles like XGBoost are effective [22]. b. Training: Split data into training, validation, and test sets. Train the model, using the validation set for hyperparameter tuning. c. Validation: Evaluate the model on the held-out test set. Use metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and R². Critically, assess extrapolation ability by testing on elements or material classes not seen during training [24] [22].

Iterative Refinement and Application: a. Analysis: Use explainable AI (XAI) techniques (e.g., SHAP, feature importance) to interpret which descriptors are driving predictions [23]. This can reveal new physical insights. b. Active Learning: Deploy the trained model to screen a large virtual library of candidate materials. Select promising candidates for subsequent DFT validation or experimental synthesis, adding these new data points to the training set to improve the model iteratively [24] [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Computational Reagents and Resources

| Tool/Resource | Function/Benefit | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) [23] | Provides high-quality ground truth data for electronic properties and energies. | Calculating target properties (e.g., adsorption energy) and electronic descriptors (e.g., d-band center). |

| Machine-Learned Force Fields (MLFFs) [24] | Enables rapid structural relaxation and energy calculation at near-DFT accuracy. | Generating geometric descriptors and AEDs for large numbers of complex structures. |

| E(3)-Equivariant Neural Networks [25] [26] | Deep learning models that respect physical symmetries for predicting quantum mechanical properties. | Directly learning the Hamiltonian or other electronic properties from atomic structure. |

| Open Catalyst Project (OCP) Datasets & Models [24] | Pre-trained MLFFs and large, curated datasets for catalysis research. | Accelerating the workflow for calculating adsorption energies and generating training data. |

| Explainable AI (XAI) Techniques [23] | Interprets "black-box" models to identify critical features and build trust. | Post-hoc analysis of ANN models to understand descriptor importance and guide feature engineering. |

| Thalidomide-NH-CH2-COO(t-Bu) | Thalidomide-NH-CH2-COO(t-Bu), MF:C19H21N3O6, MW:387.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Mercapto-2-butanone-d3 | 3-Mercapto-2-butanone-d3, MF:C4H8OS, MW:107.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The pursuit of efficient catalysts for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) is a cornerstone of developing sustainable hydrogen production technologies. Traditional methods for catalyst discovery, which often rely on empirical experimentation or computationally intensive density functional theory (DFT) calculations, struggle to navigate the vast chemical compositional space in a time-efficient manner [28]. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) and other machine learning (ML) models have emerged as powerful tools to accelerate this process by learning complex patterns from existing data to predict catalytic performance [29] [30]. A significant challenge in building robust, generalizable models lies in the "curse of dimensionality," where an excessive number of input features can lead to overfitting and reduced interpretability. This case study examines a specific research initiative that successfully developed a high-precision ML model for predicting HER activity across diverse catalyst types using a minimized set of only ten features [28]. The strategies and protocols detailed herein provide a framework for researchers aiming to construct efficient and accurate predictive models for catalyst performance.

The highlighted study achieved a high-performance predictive model for hydrogen adsorption free energy (ΔGH), a key descriptor for HER activity. The following tables summarize the quantitative outcomes and the minimal feature set used.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Models for ΔGH Prediction (10-Feature Set)

| Machine Learning Model | R² Score | Other Reported Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Extremely Randomized Trees (ETR) | 0.922 | - |

| Random Forest Regression (RFR) | - | - |

| Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR) | - | - |

| Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBR) | - | - |

| Decision Tree Regression (DTR) | - | - |

| Light Gradient Boosting (LGBMR) | - | - |

| Crystal Graph CNN (CGCNN) | Lower than ETR | - |

| Orbital Graph CNN (OGCNN) | Lower than ETR | - |

Table 2: The Minimized 10-Feature Set for HER Catalyst Prediction

| Feature Name | Description / Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Key Feature φ | φ = Nd₀²/ψ₀ - An energy-related feature highly correlated with ΔGH [28]. |

| Other Features | A curated set of nine additional features based on atomic structure and electronic information of the catalyst active sites, without requiring additional DFT calculations [28]. |

The core achievement was the development of an Extremely Randomized Trees (ETR) model that demonstrated superior predictive accuracy (R² = 0.922) using only ten features [28]. This model significantly outperformed two deep learning approaches, the Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Network (CGCNN) and the Orbital Graph Convolutional Neural Network (OGCNN), underscoring that thoughtful feature engineering can be more critical than model complexity alone [28]. Furthermore, the model demonstrated remarkable efficiency, completing predictions in approximately 1/200,000th of the time required by traditional DFT methods, and successfully identified 132 new promising HER catalysts from the Material Project database [28].

Experimental Protocols

Data Acquisition and Curation Protocol

Objective: To assemble a high-quality, labeled dataset for training and validating the HER activity prediction model. Reagents/Resources: Catalysis-hub database [28], Python programming environment, data processing libraries (e.g., Pandas, NumPy). Workflow Diagram:

Procedure:

- Data Collection: Download the initial dataset of 11,068 catalyst structures and their corresponding hydrogen adsorption free energy (ΔGH) values from the Catalysis-hub database [28].

- Energy Range Filtering: Narrow the dataset by retaining only data points where ΔGH falls within the physically meaningful range of [-2, 2] eV. This step aligns with the known principle that optimal HER catalysts have |ΔGH| close to zero [28].

- Structure Validation: Manually or algorithmically inspect and remove data points associated with unreasonable hydrogen adsorption structures (e.g., incorrect bonding geometries) to ensure data integrity.

- Final Dataset: The final curated dataset consists of 10,855 data points encompassing diverse catalyst types (pure metals, intermetallic compounds, non-metallic compounds, perovskites) and involves 42 chemical elements [28].

Feature Engineering and Model Training Protocol

Objective: To extract, select, and minimize the feature set and use it to train a high-performance ETR model. Reagents/Resources: Curated dataset, Python with ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) module, Scikit-learn or similar ML library. Workflow Diagram:

Procedure:

- Initial Feature Extraction: Use the ASE Python module to automatically identify adsorbed hydrogen atoms and material surface structures. Scripts should extract an initial set of 23 features, including electronic and elemental properties of the active site atoms and their nearest neighbors [28].

- Preliminary Model Building: Establish and compare six different ML models (RFR, GBR, XGBR, DTR, LGBMR, ETR) using the full set of 23 features to establish a baseline performance.

- Feature Importance Analysis: Run a feature importance analysis on the best-performing model (e.g., ETR) to identify which of the 23 initial descriptors contribute most significantly to the accurate prediction of ΔGH.

- Feature Set Minimization: Based on the importance analysis, reselect the features to create a new, minimized set of only ten features. This set includes the key energy-related feature φ (φ = Nd₀²/ψ₀) and nine other highly relevant structural/electronic descriptors [28].

- Final Model Training: Retrain the Extremely Randomized Trees (ETR) model using the minimized 10-feature set.

- Model Validation: Evaluate the final model's performance on a held-out test set, reporting the R² score and other relevant metrics to confirm the maintained or improved predictive power.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Driven HER Catalyst Discovery

| Item | Function / Relevance |

|---|---|

| Catalysis-hub Database | Provides a large, peer-reviewed repository of catalyst structures and corresponding adsorption energies for training reliable ML models [28]. |

| Material Project Database | A computational database used as a source of new, unexplored catalyst structures for virtual screening and prediction [28] [30]. |

| Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) | A Python module used to set up, manipulate, run, visualize, and analyze atomistic simulations; crucial for automating feature extraction from catalyst structures [28]. |

| Extremely Randomized Trees (ETR) | The ensemble ML algorithm that demonstrated highest accuracy in this study for predicting ΔGH with a minimal feature set [28]. |

| Key Feature φ (Nd₀²/ψ₀) | A engineered descriptor that encapsulates critical energy-related information and is strongly correlated with HER free energy, reducing reliance on numerous other features [28]. |

| Tubulin polymerization-IN-53 | Tubulin polymerization-IN-53, MF:C19H18ClNO6, MW:391.8 g/mol |

The escalating concentration of atmospheric CO₂ necessitates the development of efficient technologies for its conversion into valuable fuels and chemicals. Photocatalytic CO₂ reduction, which uses sunlight to drive these chemical transformations, presents a promising solution [31]. Among various catalytic materials, ferroelectric materials have emerged as particularly attractive candidates due to their unique switchable polarization, which promotes efficient charge separation—a critical factor in photocatalytic efficiency [32] [33].

The integration of Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) into this field addresses a significant challenge: the traditional trial-and-error approach to catalyst development is often slow and resource-intensive. ANNs serve as powerful predictive tools, enabling researchers to model complex relationships between a catalyst's physical properties and its photocatalytic performance, thereby accelerating the optimization process [34] [32]. This case study details the application of ANN modeling to enhance the photocatalytic COâ‚‚ reduction performance of ferroelectric materials, providing application notes and detailed protocols for researchers.

Key Performance Parameters and Quantitative Relationships

The performance of ferroelectric photocatalysts is governed by several intrinsic and operational parameters. Understanding these relationships is crucial for both experimental design and model development. The following table summarizes the key input parameters and their impact on critical performance metrics, as identified from experimental and modeling studies [32].

Table 1: Key Parameters Influencing Ferroelectric Photocatalyst Performance

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameter | Impact on Photocatalytic Process |

|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic Material Properties | Band Gap (eV) | Determines the range of solar spectrum absorbed; narrower band gaps generally enhance visible light absorption [32]. |

| Polarization (µC/cm²) | The internal electric field from switchable polarization enhances charge separation, reducing electron-hole recombination [32] [33]. | |

| Structural Characteristics | Surface Area (m²/g) | A higher surface area provides more active sites for CO₂ adsorption and surface reactions [32]. |

| Crystal Structure & Phase | Affects polarization strength, charge mobility, and overall catalytic activity. | |

| Performance Metrics | Charge Separation Efficiency (%) | Directly influences the number of available charge carriers for the reduction reaction [32]. |

| Light Absorption Efficiency (%) | Measures the material's effectiveness in utilizing incident light [32]. | |

| Product Selectivity (e.g., CH₄, CO, CH₃OH) | Determined by the interaction of activated CO₂ and intermediates with the catalyst surface. |

ANN modeling has been successfully employed to map these complex, non-linear relationships. For instance, a shallow neural network can predict outputs like charge separation (%), light absorption (%), and surface area based on inputs such as band gap and polarization [32]. The predictive accuracy of such models is often validated using linear regression analysis, correlating predicted values with experimental measurements [32].

Experimental Protocol for Catalyst Synthesis and Evaluation

This section provides a detailed methodology for preparing, characterizing, and testing ferroelectric photocatalysts, forming the foundational dataset for ANN training.

Catalyst Synthesis via Precipitation

The following protocol, adapted from a study on cobalt-based catalysts, can be modified for ferroelectric material synthesis [35].

- Objective: To synthesize a ferroelectric catalyst precursor with controlled composition and morphology.

- Materials:

- Metal precursor salt (e.g., Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, Bi(NO₃)₃, NaTaO₃).

- Precipitating agent (e.g., Oxalic Acid (H₂C₂O₄), Sodium Carbonate (Na₂CO₃), Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH)).

- Deionized Water.

- Procedure:

- Prepare a 0.2 M aqueous solution of the metal precursor salt in 100 mL deionized water.

- In a separate container, prepare a 0.22 M aqueous solution of the precipitating agent in 100 mL deionized water. Note: A slight excess of precipitant ensures complete conversion of the metal precursor [35].

- Under continuous stirring at room temperature, add the precipitant solution dropwise to the metal salt solution. Continue stirring for 1 hour to complete the precipitation reaction.

- Separate the resulting precipitate by centrifugation.

- Wash the precipitate repeatedly with deionized water until the washings reach a neutral pH.

- Transfer the washed precipitate to a Teflon-lined autoclave and heat at 80°C for 24 hours for hydrothermal treatment.

- Recover the solid via centrifugation and dry it in an oven at 80°C overnight.

- Finally, calcine the dried precursor in a furnace under a static air atmosphere at a temperature and duration specific to the target ferroelectric phase (e.g., 500-700°C for 2-4 hours).

Photocatalytic COâ‚‚ Reduction Testing

- Objective: To evaluate the performance of the synthesized ferroelectric catalyst in reducing COâ‚‚ under simulated sunlight.

- Materials:

- Photocatalytic reactor system with a gas-closed circulation setup.

- Light source (e.g., 300 W Xe lamp simulating solar spectrum).

- High-purity COâ‚‚ gas.

- Water vapor source.

- Gas Chromatograph (GC) equipped with a Flame Ionization Detector (FID) and Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD).

- Procedure:

- Disperse 20 mg of the photocatalyst powder in a designated area of the reaction chamber.

- Seal the reactor and evacuate the system to remove all air.

- Introduce a mixture of COâ‚‚ and water vapor into the reactor. The total pressure should be maintained at ambient or slightly elevated levels.

- Turn on the light source to initiate the photocatalytic reaction. Ensure consistent cooling to maintain room temperature.

- At regular intervals (e.g., every hour), withdraw a small volume of gas from the reaction chamber using a gas-tight syringe.

- Inject the gas sample into the GC for quantitative analysis of reaction products (e.g., CH₄, CO, CH₃OH).

- Calculate key performance indicators such as product evolution rate (µmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹) and product selectivity (%).

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational workflow for optimizing photocatalysts.

ANN Modeling Protocol for Performance Prediction

This protocol outlines the process of developing an ANN model to predict and optimize ferroelectric photocatalyst performance.

- Objective: To construct a robust ANN model that maps ferroelectric material properties to photocatalytic COâ‚‚ reduction efficiency.

Software/Tools: Python (with libraries like Scikit-Learn, TensorFlow, or PyTorch) or a custom Fortran program [35] [32].

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition and Curation:

- Compile a high-quality dataset from experimental results (see Section 3). The dataset should include input features (e.g., band gap, polarization, surface area) and target outputs (e.g., charge separation efficiency, yield of specific products like CHâ‚„) [34].

- Clean the data by handling missing values and removing outliers.

- Normalize or standardize the dataset to ensure all features are on a similar scale, which improves model training stability and convergence.

- Model Architecture and Training:

- Network Selection: A feedforward neural network with one hidden layer (a "shallow" network) has been successfully applied in similar studies [32].

- Input/Output Layers: The number of nodes in the input and output layers should match the number of selected features and target variables, respectively.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Systematically vary hyperparameters such as the number of neurons in the hidden layer, learning rate, and activation functions (e.g., ReLU, Sigmoid). One study trained 600 different ANN configurations to identify the optimal model [35].

- Training: Split the dataset into training, validation, and test sets (e.g., 70/15/15). Use the training set to adjust the model weights and the validation set to monitor for overfitting and tune hyperparameters.

- Model Evaluation and Optimization:

- Evaluate the final model on the held-out test set. Common metrics include Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for regression tasks. A well-trained model should show MAEs for energy predictions within ± 0.1 eV/atom and for forces within ± 2 eV/Å, as demonstrated in advanced neural network potentials [36].

- Use the trained model for in-silico screening and optimization. By providing desired performance targets, the model can reverse-predict the optimal combination of material properties.

- Data Acquisition and Curation:

ANN Optimization Pathway

The logical flow of the ANN-driven optimization process is depicted below.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The following table catalogs key materials and their functions for research in ferroelectric photocatalyst development and testing.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cobalt Nitrate Hexahydrate | Metal precursor for synthesizing cobalt-based oxide catalysts (e.g., Co₃O₄) [35]. | Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O (Sigma-Aldrich, 98% purity). A common starting material for precipitation. |

| Oxalic Acid | Precipitating agent for generating specific catalyst precursors with controlled morphology [35]. | H₂C₂O₄•2H₂O (Alfa Aesar, 98% purity). Reacts with metal salts to form insoluble oxalates. |

| Sodium Carbonate | Precipitating agent for generating carbonate precursors [35]. | Na₂CO₃ (Sigma-Aldrich, 99% purity). |

| Titanium Dioxide (TiOâ‚‚) | Benchmark photocatalyst for performance comparison [32]. | P25 (Degussa) is widely used as a reference material. |

| Ferroelectric Powder (e.g., BiFeO₃) | Model ferroelectric photocatalyst for fundamental studies [33]. | Bismuth Ferrite is a popular multiferroic material studied for CO₂ reduction. |

| High-Purity COâ‚‚ Gas | Reactant source for photocatalytic reduction experiments [31]. | Enables testing under controlled atmospheres, including low-concentration (5-20%) simulations. |

| Xenon Lamp Light Source | Simulates the solar spectrum for laboratory-scale photocatalytic testing [32]. | 300 W Xe lamp is commonly used to provide full-spectrum or filtered light. |

Application Note: Leveraging Advanced Neural Networks in Catalytic Research

The integration of artificial intelligence, particularly graph neural networks (GNNs) and conditional variational autoencoders (CVAEs), is revolutionizing catalyst design by moving beyond traditional trial-and-error and computational methods. These architectures enable accurate prediction of catalytic properties and the generative design of novel catalyst candidates, significantly accelerating the discovery pipeline [37] [38]. This note details their operational principles, performance benchmarks, and practical implementation protocols to equip researchers with the tools needed for modern, data-driven catalyst development.

GNNs are exceptionally suited for chemical problems because they operate directly on graph representations of molecules, where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges. This allows them to inherently capture structural information that is crucial for understanding catalytic behavior [38]. The Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN) framework is a dominant paradigm, where information from neighboring atoms is iteratively aggregated to build informative molecular representations [39] [38]. For generative tasks, CVAEs offer a powerful framework for creating novel molecular structures. They learn a compressed, continuous latent space of catalyst designs and can generate new candidates from this space when conditioned on specific reaction contexts or desired properties [37] [40].

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Table 1: Performance of GNN Architectures for Catalytic Yield Prediction

| GNN Architecture | Application Context | Performance (R²) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN) | Cross-coupling reactions | 0.75 [39] | Highest predictive accuracy on heterogeneous datasets |

| Graph Attention Network (GAT) | Cross-coupling reactions | Benchmarkable [39] | Dynamic attention weights for neighbors |

| Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN) | Cross-coupling reactions | Benchmarkable [39] | High expressive power for graph structures |

| Residual Graph Convolutional Network (ResGCN) | Cross-coupling reactions | Benchmarkable [39] | Mitigates vanishing gradients in deep networks |

Table 2: Capabilities of Conditional Generative Models for Catalyst Design

| Model Architecture | Core Function | Conditioning Input | Key Outcome/Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|

| CatDRX (CVAE-based) [37] | Catalyst generation & yield prediction | Reaction components (reactants, reagents, etc.) | Generates novel catalysts for given reaction conditions |

| ICVAE (Interpretable CVAE) [40] | De novo molecular design | Target molecular properties (e.g., HBA, LogP) | Establishes a linear mapping between latent variables and properties |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Training a GNN for Catalytic Property Prediction

Objective: To train a Graph Neural Network for predicting reaction yields or other catalytic performance metrics. Key Reagents & Computational Tools: See Table 4 in Section 5.

Workflow:

- Dataset Curation: Assemble a dataset of catalytic reactions with annotated outcomes (e.g., yield, enantioselectivity). Representative examples include the Open Reaction Database (ORD) [37] or specialized datasets for cross-coupling reactions [39].

- Graph Representation: Convert each molecular species (catalyst, reactant, product) into a graph. This involves:

- Node Features: Atomic number, chirality, formal charge, etc.

- Edge Features: Bond type, conjugation, stereochemistry [38].

- Model Architecture Selection: Choose a GNN variant (e.g., MPNN, GIN, GAT). The MPNN framework is a robust starting point [39].

- Training & Validation:

- Split the data into training, validation, and test sets.

- Train the model using a regression loss function (e.g., Mean Squared Error) to predict the target property.

- Use the validation set for hyperparameter tuning and early stopping.