Bridging Theory and Experiment: A Practical Guide to Validating Computational Catalyst Descriptors

The integration of computational catalyst descriptors with experimental validation is revolutionizing catalyst discovery, creating a powerful, iterative design loop.

Bridging Theory and Experiment: A Practical Guide to Validating Computational Catalyst Descriptors

Abstract

The integration of computational catalyst descriptors with experimental validation is revolutionizing catalyst discovery, creating a powerful, iterative design loop. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists navigating this interdisciplinary landscape. We first explore the foundational role of descriptors like adsorption energies and their evolution with machine learning. The discussion then progresses to advanced methodological frameworks, including high-throughput workflows and generative models, that accelerate screening. A critical examination of current challenges—from data quality to model interpretability—is provided, alongside robust validation protocols and comparative analyses of emerging techniques. By synthesizing insights from recent benchmarks and case studies, this review serves as a strategic roadmap for the rigorous experimental validation that is essential for deploying computational predictions in real-world catalytic applications, including those relevant to pharmaceutical development.

The Bedrock of Catalytic Understanding: From Traditional Descriptors to AI-Enhanced Proxies

Catalytic descriptors are quantitative or qualitative measures that capture key properties of a system, serving as essential tools for understanding the relationship between a material's structure and its function [1]. These descriptors facilitate the design and optimization of new catalytic materials and processes, creating a crucial link between electronic structure and macroscopic performance. The evolution of descriptors began in the 1970s with Trasatti's pioneering work using the heat of hydrogen adsorption on different metals to describe the hydrogen evolution reaction [1]. This established the fundamental paradigm of using descriptors to connect atomic-scale properties to catalyst activity and selectivity.

In modern chemical and energy industries, descriptors serve as core tools for enabling precision catalysis by guiding atomic-scale design to enhance selectivity and efficiency while reducing precious-metal usage and pollution [1]. They underpin sustainable processes such as green synthesis and wastewater treatment, while also optimizing performance of key materials in fuel cells, water electrolysis, and related technologies [1]. This review examines the evolution of catalytic descriptors from early energy-based models to contemporary electronic and data-driven approaches, focusing on their experimental validation and practical application in catalyst design.

The Evolution of Catalytic Descriptors: From Energy-Based to Data-Driven Approaches

Energy Descriptors: The Foundation

Energy descriptors represent the foundational approach to quantifying catalytic properties, primarily analyzing the Gibbs free energy or binding energy of reaction intermediates [1]. These descriptors emerged from Trasatti's early work on hydrogen atom adsorption energies for the hydrogen evolution reaction, which demonstrated that optimal catalyst activity occurs when adsorption energy reaches approximately 55 kcal/mol [1]. This established the fundamental relationship between catalyst activity and adsorption energy that continues to inform catalyst design.

A critical development in energy descriptors was the recognition of "scaling" relationships between adsorption free energies of surface intermediates, expressed as ΔG₂j = A × ΔG₁j + B, where A and B are constants dependent on the geometric configuration of the adsorbate or adsorption site [1]. These relationships simplified material design but also revealed inherent limitations in electrocatalytic efficiency. The Brønsted-Evans-Polanyi (BEP) relationship further established linear connections between dissociation activation energy and chemisorption free energy across various metal reaction sites [1]. Both adsorption energy and transition state energy in catalytic reactions are strongly influenced by these relationships, which limit the ability of energy descriptors to fully capture the electronic properties of metal surfaces.

Table 1: Types of Energy Descriptors and Their Applications

| Descriptor Type | Key Formulation | Catalytic Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption Energy | ΔG of intermediates | HER, ORR, ammonia synthesis | Limited electronic structure information |

| Scaling Relationships | ΔG₂j = A × ΔG₁j + B | Material design simplification | Constrains efficiency optimization |

| BEP Relationship | Linear connection between Eₐ and ΔG | Prediction of activation energies | Does not capture full surface electronic properties |

Electronic Descriptors: The d-Band Center Theory

In the 1990s, Jens Nørskov and Bjørk Hammer introduced the d-band center theory for transition metal catalysts, marking a significant advancement in electronic descriptors [1]. This theory demonstrated how the position of the d-band center relative to the Fermi level influences adsorption capacity of adsorbates on metal surfaces, providing crucial insights into catalyst activity and selectivity from a microscopic perspective [1]. The d-band center theory established a groundbreaking correlation between the average energy of d-orbital levels and adsorption strength, offering valuable information about electronic structure across different scales.

For transition metals, the total electronic band structure divides into sp, d, and other bands, with the d-band playing a crucial role in adsorption behavior [1]. Higher d-band center energies generally lead to stronger adsorbate bonding due to elevated anti-bonding state energies, while catalysts with low d-state energies often fill anti-bonding states, weakening adsorption bonds [1]. The d-band center is typically calculated using density functional theory (DFT) by analyzing the density of states for d-orbitals, mathematically expressed as εd = ∫Eρd(E)dE / ∫ρd(E)dE, where E is the energy relative to the Fermi level [1]. Despite its limitations with strongly correlated oxides or systems where reaction kinetics outweigh thermodynamics, the d-band center remains a cornerstone in understanding how metal surfaces interact with adsorbates.

Data-Driven Descriptors: The Machine Learning Revolution

Recent advances in computational methods and big data integration have catalyzed the development of data-driven descriptors in catalytic site design [1]. By integrating machine learning, high-throughput screening, and in situ characterization, descriptors are evolving into dynamic, intelligent tools that propel catalytic materials from empirical design to a theory-driven industrial revolution [1]. These approaches enable precise predictions of catalytic performance by incorporating key physicochemical properties such as electronegativity and atomic radius to establish mathematical relationships between catalyst structure and adsorption energy [1].

A novel approach in this domain is the Adsorption Energy Distribution descriptor, which aggregates binding energies for different catalyst facets, binding sites, and adsorbates [2]. This versatile descriptor can be adjusted to specific reactions through careful selection of key-step reactants and reaction intermediates, providing a more comprehensive representation of catalyst behavior than single-facet descriptors [2]. Machine learning force fields have been instrumental in enabling large-scale screening with these complex descriptors, offering speed increases of 10⁴ or more compared to traditional DFT calculations while maintaining quantum mechanical accuracy [2].

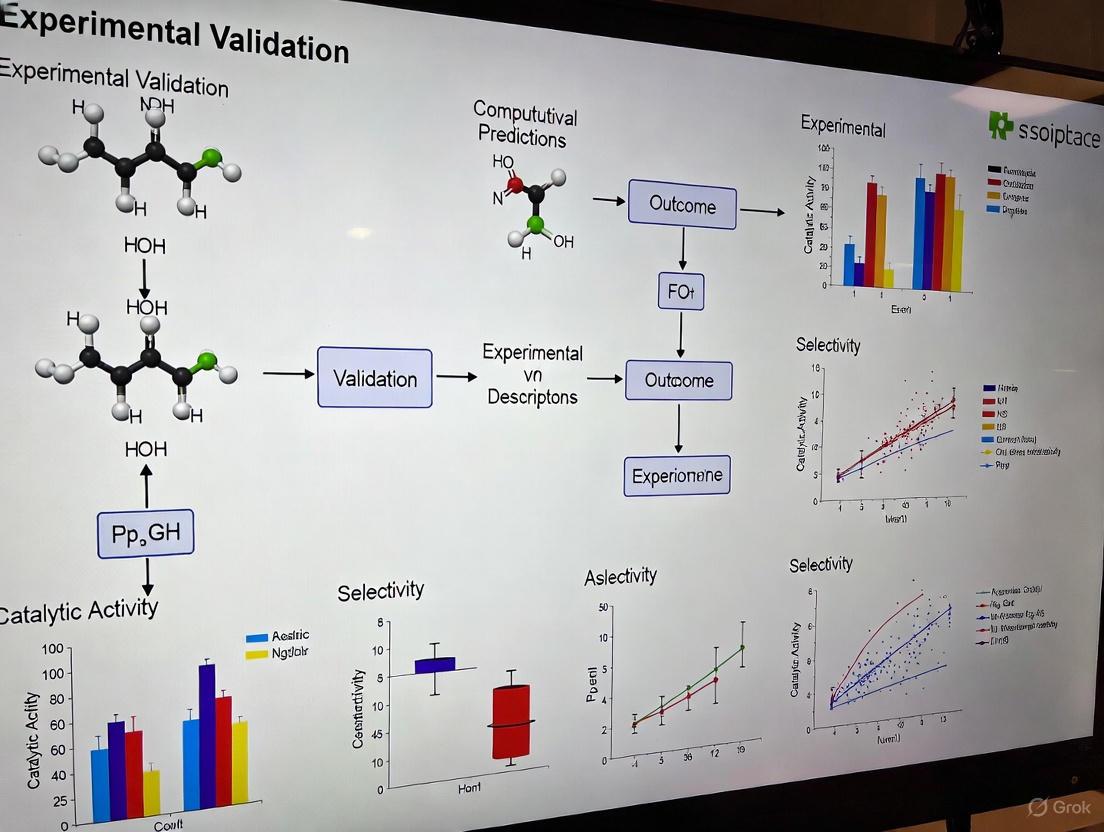

Experimental Validation of Descriptor-Based Predictions

Volcano Plot Paradigm and Experimental Confirmation

The volcano plot paradigm represents a widely validated approach in descriptor-based catalyst design, where binding strength of one or few simple adsorbates estimates catalytic rate based on the principle that binding strength should be neither too strong nor too weak [3]. This approach has demonstrated remarkable success across various reactions. For NH₃ electrooxidation, a volcano plot based on bridge- and hollow-site N adsorption energies correctly predicted that Pt₃Ir and Ir would be more active than Pt [3]. Subsequent screening for Ir-free trimetallic electrocatalysts featuring {100}-type site motifs forecasted site reactivity, surface stability, and catalyst synthesizability descriptors, leading to the experimental realization of Pt₃Ru₁/₂Co₁/₂ catalysts which demonstrated superior mass activity toward ammonia oxidation compared to Pt, Pt₃Ru, and Pt₃Ir catalysts [3].

Similar success has been achieved in volcano plot applications for alkane dehydrogenation. For ethane dehydrogenation, C and CH₃ adsorption energies were chosen as computationally facile descriptors [3]. Using a decision map to screen beyond the volcano plot, Ni₃Mo was identified as a promising candidate. Experimental validation confirmed that Ni₃Mo/MgO achieved an ethane conversion of 1.2%, three times higher than the 0.4% conversion for Pt/MgO under identical reaction conditions [3]. For propane dehydrogenation, DFT calculations combined with machine learning identified CH₃CHCH₂ and CH₃CH₂CH as optimal descriptors, leading to the experimental confirmation that NiMo/Al₂O₃ showed better performance over Pt/Al₂O₃ in selectivity, activity, and stability over time [3].

Table 2: Experimentally Validated Descriptor Predictions in Catalyst Design

| Catalytic System | Descriptor Used | Predicted Performance | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pt₃Ru₁/₂Co₁/₂ | N adsorption energies | Superior NH₃ oxidation activity | Higher mass activity vs Pt, Pt₃Ru, Pt₃Ir [3] |

| Ni₃Mo/MgO | C and CH₃ adsorption energies | Enhanced ethane dehydrogenation | 3× higher conversion than Pt/MgO [3] |

| NiMo/Al₂O₃ | CH₃CHCH₂ and CH₃CH₂CH adsorption | Better propane dehydrogenation | Superior selectivity, activity, stability vs Pt/Al₂O₃ [3] |

| RhCu/SiO₂ SAA | Transition state energy for C–H scission | High activity and stability | More active and stable than Pt/Al₂O₃ [3] |

Advanced Workflows for Descriptor Validation

Sophisticated computational workflows have been developed to enhance the predictive power and experimental relevance of descriptor-based approaches. For CO₂ to methanol conversion, a comprehensive workflow incorporating adsorption energy distributions (AEDs) as descriptors has been established [2]. This workflow begins with search space selection, isolating metallic elements previously experimented with for CO₂ thermal conversion that are also part of the Open Catalyst 2020 database [2]. Following materials compilation, crucial adsorbates including *H, *OH, *OCHO, and *OCH₃ are selected based on experimental identification as essential reaction intermediates [2].

The validation phase employs machine learning force fields from the Open Catalyst Project, enabling rapid computation of adsorption energies across multiple facets and binding sites [2]. To ensure reliability, a robust validation protocol benchmarks MLFF predictions against explicit DFT calculations, with reported mean absolute error of 0.16 eV for adsorption energies falling within acceptable accuracy ranges [2]. The resulting AEDs capture the spectrum of adsorption energies across various facets and binding sites of nanoparticle catalysts, providing a more realistic representation of industrial catalysts composed of nanostructures with diverse surface facets and adsorption sites [2]. This approach has identified promising candidate materials such as ZnRh and ZnPt₃ for CO₂ to methanol conversion [2].

Methodologies and Protocols for Descriptor Analysis

Computational Framework and Workflow

The integration of machine learning force fields (MLFFs) has revolutionized descriptor-based catalyst screening by enabling rapid computation of adsorption energies across multiple material facets and configurations. The typical workflow for adsorption energy distribution analysis involves several key stages [2]:

- Search Space Selection: Identification of metallic elements with prior experimental validation for the target reaction that are also represented in training databases such as OC20 [2].

- Materials Compilation: Gathering stable and experimentally observed crystal structures from materials databases, followed by bulk DFT optimization to ensure structural consistency [2].

- Surface Generation: Creating surfaces with various Miller indices and selecting the most stable terminations for further analysis [2].

- Adsorbate Configuration: Engineering surface-adsorbate configurations for key reaction intermediates across all relevant facets and binding sites [2].

- Energy Calculation: Optimizing configurations and calculating adsorption energies using MLFFs, with selective validation against explicit DFT calculations [2].

- Descriptor Analysis: Applying unsupervised learning techniques to analyze AEDs, including similarity quantification using metrics like Wasserstein distance and hierarchical clustering to group catalysts with similar AED profiles [2].

This workflow enables the generation of extensive datasets, such as the collection of over 877,000 adsorption energies across nearly 160 materials relevant to CO₂ to methanol conversion, providing comprehensive energy landscapes for catalyst evaluation [2].

Experimental Validation Protocols

Experimental validation of computationally designed catalysts requires careful characterization to ensure correspondence between predicted and synthesized materials. Successful validation protocols typically incorporate multiple complementary techniques [3]:

- Structural Characterization: High-angle annular dark-field-scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) confirm predicted nanostructures and crystal phases [3].

- Surface Analysis: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) provides information about surface composition and oxidation states [3].

- Performance Testing: Reactor experiments under controlled conditions measure conversion rates, selectivity, and stability over time [3].

- Electrochemical Evaluation: For electrocatalysts, cyclic voltammetry in standardized electrolytes quantifies mass activity and compares performance against reference catalysts [3].

A critical consideration in experimental validation is ensuring that experiments probe materials and surface structures similar to those proposed by computations, as discrepancies can lead to serendipitous agreement rather than true validation of design principles [3]. Additionally, material stability is crucial when experimental validation is desired but not necessarily required when investigating fundamental trends in chemical properties [3].

Essential Research Tools and Solutions

The advancement of descriptor-based catalyst design relies on specialized computational tools and platforms that enable efficient calculation and analysis. Key resources include:

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Descriptor-Based Catalyst Design

| Tool/Platform | Function | Application in Descriptor Design |

|---|---|---|

| Open Catalyst Project (OCP) | Provides machine learning force fields | Enables rapid calculation of adsorption energies with 10⁴ speed increase vs DFT [2] |

| Materials Project Database | Repository of crystal structures and properties | Source of stable and experimentally observed structures for screening [2] |

| DFT Software (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) | Quantum mechanical calculations | Benchmarking MLFF predictions and calculating electronic descriptors [1] [2] |

| DeepAutoQSAR | Machine learning platform | Training predictive models for molecular properties beyond small molecules [4] |

| Symbolic Regression | Identifies mathematical relationships | Creates models for adsorption energies based on fundamental properties [3] |

Experimental Characterization Techniques

Validating computationally designed catalysts requires sophisticated characterization methodologies to confirm predicted structures and performance:

- High-Resolution Microscopy: HAADF-STEM provides atomic-resolution imaging of nanoparticle catalysts, confirming predicted structures and compositions [3].

- Surface Spectroscopy: XPS analyzes surface composition and oxidation states, verifying the presence of predicted active sites [3].

- X-ray Diffraction: Confirms crystal phases and structural matches to computational models [3].

- Electrochemical Characterization: Cyclic voltammetry and related techniques quantify catalytic activity under standardized conditions for fair comparison between predicted and reference catalysts [3].

- Reactor Testing: Measures conversion, selectivity, and stability under operational conditions, providing critical validation of predicted performance [3].

The evolution of catalytic descriptors from simple energy-based measures to sophisticated data-driven representations has fundamentally transformed catalyst design methodologies. The successful experimental validation of descriptor-based predictions across diverse catalytic systems—from hydrogen evolution and ammonia oxidation to alkane dehydrogenation and CO₂ conversion—demonstrates the maturity of these approaches [1] [2] [3]. The integration of machine learning force fields with comprehensive descriptor frameworks such as adsorption energy distributions has addressed critical limitations of traditional single-facet descriptors, enabling more realistic representation of complex industrial catalysts [2].

Future advancements in descriptor development will likely focus on increasing dynamic and operational relevance by incorporating environmental factors such as electrolyte composition, pH, solvent properties, and interfacial electric fields that regulate descriptor applicability [1]. The integration of experimental data with computational predictions will be essential for developing descriptors that accurately reflect realistic reaction conditions rather than idealized computational environments [5]. As these trends continue, catalytic descriptors will evolve into increasingly intelligent tools that propel catalyst design from empirical exploration toward predictive science, ultimately accelerating the development of sustainable energy technologies and chemical processes.

In the rational design of catalysts, three interconnected concepts form a foundational canon: adsorption energies, the d-band center, and scaling relations. Adsorption energy, quantifying the strength of interaction between a reaction intermediate and a catalyst surface, is a direct determinant of catalytic activity and selectivity. [6] The d-band center theory, a powerful electronic descriptor, provides a predictive framework for understanding and computing these adsorption energies by relating them to the local electronic structure of the catalyst's surface. [7] [8] Furthermore, linear scaling relationships (LSRs) are observed universal correlations between the adsorption energies of different intermediates on catalytic surfaces. [9] [10] These relationships simplify catalyst screening but also impose fundamental limitations on achieving peak catalytic performance for multi-step reactions. [11] This guide objectively compares the performance of these conceptual "tools" and their interplay, framing the discussion within the critical context of experimental and computational validation.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Principles

The d-Band Center Theory

The d-band center theory, pioneered by Hammer and Nørskov, has become a cornerstone in surface science and catalysis. It posits that the weighted average energy of the d-band electronic states (εd) relative to the Fermi level is a key descriptor for a transition metal's surface reactivity. [7] The principle is that an up-shifted d-band center (closer to the Fermi level) strengthens the adsorption of reactive intermediates due to enhanced coupling between adsorbate states and metal d-states, while a down-shifted d-band center typically leads to weaker binding. [7] [12] This theory provides a mechanistic explanation for catalytic activity trends across different transition metals and their alloys.

Scaling Relations in Catalysis

Scaling relations are linear correlations between the adsorption energies of different adsorbates on a series of catalytic surfaces. For instance, the adsorption energies of *AHx intermediates (e.g., *OH, *NH2, *CH3) often scale linearly with the adsorption energy of the central atom *A (e.g., *O, *N, *C). [9] [10] These relations arise because the variation in adsorption energy from one metal to another is proportional to the surface-adsorbate bond order. [10] A key parameter is the valence parameter γ(x), defined as (x~max~ - x)/x~max~, where x~max~ is the maximum number of hydrogen atoms satisfying the octet rule for the atom A. [10] This model has been successfully extended from simple hydrogenated atoms to more complex C~2~ hydrocarbon species. [10]

Comparative Performance Analysis of Catalytic Descriptors

The table below provides a quantitative comparison of the three core concepts, their performance as predictors, and their validated limitations.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Core Catalytic Descriptors

| Descriptor | Fundamental Principle | Predictive Performance & Limitations | Experimental/Computational Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption Energy | Strength of interaction between adsorbate and catalyst surface. [6] | Direct determinant of activity; high-fidelity benchmark for theory. [6] | Benchmark databases of experimental values exist for validating DFT functionals. [6] |

| d-Band Center | Reactivity correlates with energy of d-states relative to Fermi level. [7] | Explains trends for simple surfaces; less accurate for complex systems with strong correlations or magnetism. [7] [12] | Used to design Rh–P nanoparticles; activity correlated with d-band center deviation (R² = 0.994). [8] |

| Scaling Relations | Linear correlations between adsorption energies of different intermediates. [9] [10] | Simplify screening but limit optimization of multi-step reactions. [9] [11] | Hold for *AH~x~ on uniform surfaces; [10] can break on alloys with different site symmetries. [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Descriptor Validation

Protocol for d-Band Center Modulation and Activity Measurement

This protocol outlines the process of tuning the d-band center via alloying and measuring its effect on catalytic performance, as demonstrated in bimetallic nickel-based compounds.

- Catalyst Synthesis: Construct bimetallic compounds (e.g., Ni~3~X where X = V, Mn, Fe, Co, Cu, Zn) using controlled deposition or synthetic alloying methods. [12]

- Electronic Structure Characterization:

- Perform X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) to determine surface oxidation states.

- Use synchrotron-based X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) to probe the local electronic structure.

- Calculate the d-band center (ε~d~) from the density of states derived from DFT calculations using the formula: ε~d~ = ∫~-∞~^E~F~^ ε n~d~(ε) dε / ∫~-∞~^E~F~^ n~d~(ε) dε. [12]

- Adsorption Energy Measurement: Calorimetrically measure adsorption energies of probe molecules (e.g., glycerol) or use DFT computations to calculate binding strengths on different surfaces. [12]

- Catalytic Performance Testing: Evaluate activity for target reactions (e.g., glycerol electro-oxidation) in an electrochemical cell, measuring metrics such as reaction rate and overpotential. [12]

- Correlation Analysis: Statistically correlate the measured d-band center values with experimental adsorption energies and catalytic activity metrics to establish predictive relationships. [12]

Protocol for Probing Scaling Relations on Complex Alloy Surfaces

This methodology assesses the fidelity of scaling relationships on non-uniform surfaces like high-entropy alloys (HEAs), combining machine learning and DFT.

- High-Throughput Data Generation:

- Perform ~25,000 DFT calculations on slab models with varied chemical compositions and adsorption sites to generate adsorption energies for intermediates like *AH~x~. [9]

- Machine Learning Model Development:

- Train a deep neural network (DNN) using the DFT database. Input features should include element-specific data (e.g., electronegativity), metal-specific features (e.g., d-band center), and geometrical site information. [9]

- Use the validated model to rapidly predict adsorption energies across a vast spectrum of local environments on the HEA surface (e.g., CoMoFeNiCu). [9]

- Analysis of Scaling:

- Plot adsorption energies of different intermediates (e.g., *N vs. *NH~2~) against each other.

- Analyze whether linear correlations hold for sites with identical symmetry and across the configuration-averaged energies for the entire HEA composition. [9]

- Identify the emergence of "local scaling relationships," a weaker form of scaling that still restricts catalyst optimization. [9]

Breaking the Scaling Relations: Emerging Strategies and Experimental Validation

The limitations imposed by LSRs have motivated research into strategies for circumventing them. The table below summarizes key approaches and their experimental support.

Table 2: Experimental Strategies for Disrupting Linear Scaling Relationships

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Experimental System & Validation | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Structural Regulation | Active site undergoes coordination evolution during catalysis, altering electronic structure for different steps. [11] | Ni-Fe~2~ molecular catalyst for OER; validated by operando XAFS and AIMD. [11] | Dynamic Ni-adsorbate coordination modulates adjacent Fe site, simultaneously lowering energy barriers for O–H cleavage and O–O formation. [11] |

| Utilization of Different Site Symmetries | Different intermediates prefer distinct adsorption geometries on alloy surfaces, breaking universal correlations. [9] | CoMoFeNiCu HEA surfaces; validated by a site-specific DNN model trained on DFT. [9] | Scaling between *A and *AH~x~ only holds with identical site symmetry, unlike on uniform surfaces. [9] |

| Dual-Site or Multifunctional Cooperation | Different intermediates bind to different sites or are stabilized by nearby chemical groups (e.g., proton acceptors). [11] | Ni-Fe~2~ trimer for OER. [11] | Enables simultaneous stabilization of OOH and destabilization of *OH, breaking the *OH-OOH scaling relation. [11] |

The following diagram illustrates the logical pathway from the problem posed by scaling relations to the strategies developed to overcome them, highlighting the dynamic structural regulation mechanism.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This section details key computational and experimental tools essential for research in this field.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Computational Tools for Catalyst Descriptor Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function & Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Quantum mechanical method for computing adsorption energies, electronic structures, and reaction pathways. [9] [10] | Using RPBE functional to calculate adsorption energies of C~2~H~x~ species on transition metals. [10] |

| Machine Learning (ML) Models | Accelerate prediction of material properties and discovery of patterns in large datasets beyond DFT. [9] [5] | Deep neural network (DNN) trained on ~25k DFT calculations to predict HEA adsorption energies. [9] |

| Operando Spectroscopy | Characterizes the structure and electronic state of catalysts under actual working conditions. [11] | Operando X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) to identify Ni-Fe~2~ trimer active site during OER. [11] |

| High-Entropy Alloy (HEA) Nanoparticles | Platform with complex surface environments to test breaking of traditional scaling relations. [9] | CoMoFeNiCu HEA nanoparticles synthesized via carbothermal shock or aerosol methods. [9] |

| Bimetallic Promoters (Ni~3~X) | Tune the d-band center and magnetic properties of a host metal to optimize adsorption. [12] | Ni~3~Co and Ni~3~Cu for tuning glycerol chemisorption in electro-oxidation. [12] |

The established canon of adsorption energies, the d-band center, and scaling relations provides a powerful, interconnected framework for understanding and predicting catalytic behavior. While d-band center theory offers a foundational electronic descriptor, and scaling relations reveal universal thermodynamic constraints, their limitations in complex systems are now clear. Experimental and computational advances demonstrate that these relationships are not immutable. The emergence of dynamic active sites and engineered heterogeneity in alloys and high-entropy systems offers viable paths to circumvent these constraints. The future of rational catalyst design lies in integrating high-fidelity computational models, including machine learning, with robust experimental validation using operando techniques, ultimately enabling the tailored design of catalysts that break the traditional scaling rules for superior performance.

The discovery and optimization of catalysts have long been governed by empirical trial-and-error approaches and theoretical simulations, both of which face significant limitations when navigating vast chemical spaces and complex catalytic systems [13]. In this challenging landscape, catalytic descriptors—key parameters that correlate with catalytic activity—have served as essential compass points, guiding researchers toward promising candidates. Traditional descriptors, such as the d-band center for metal surfaces or adsorption energies of key intermediates, have provided valuable insights but often remain constrained to specific material families or surface facets [2] [14].

The emergence of machine learning (ML) has catalyzed a fundamental transformation in descriptor discovery, shifting the paradigm from intuition-driven design to data-driven computational frameworks. This evolution spans three distinct phases: initial data-driven screening, physics-based modeling, and the current stage characterized by symbolic regression and theory-oriented interpretation [13]. ML techniques now enable researchers to not only predict known descriptors with quantum mechanical accuracy but also to uncover novel, complex descriptors that capture the multifaceted nature of catalytic systems, from single-atom catalysts to high-entropy alloys and supported nanoparticles [14] [15]. This article examines the experimental validation of this computational revolution, comparing the performance of traditional and ML-accelerated approaches across diverse catalytic scenarios.

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. ML-Enhanced Descriptor Frameworks

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional and ML-Enhanced Descriptor Approaches

| Aspect | Traditional Descriptors | ML-Enhanced Descriptors | Performance Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development Approach | Theory-driven or empirical intuition | Data-driven discovery from large datasets | Automated pattern recognition |

| Computational Cost | High (requires extensive DFT calculations) | Low (after model training) | 3-4 orders of magnitude acceleration [14] |

| Scope & Transferability | Often limited to specific material families or facets | Broad applicability across diverse materials | Universal models for complex systems (HEAs, nanoparticles) [15] |

| Complexity Handling | Simple, single-property descriptors | Multi-faceted, composite descriptors | Captures non-linear relationships and complex interactions |

| Interpretability | High physical/chemical intuition | Variable (from black-box to explainable AI) | XCAI frameworks maintain interpretability [16] |

| Accuracy | Varies with approximation quality | Near-DFT accuracy for energies | MAEs <0.1 eV for adsorption energies [2] [15] |

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks of ML Models for Descriptor Prediction

| ML Model | Application Context | Prediction Accuracy | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equivariant GNN (equivGNN) | Metallic interfaces, diverse adsorbates | MAE <0.09 eV for binding energies [15] | Large, diverse datasets |

| SchNet4AIM | Real-space chemical descriptors (QTAIM/IQA) | Accurate atomic charges & interaction energies [16] | ~5,000 QTAIM calculations |

| Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR) | Cu single-atom alloys, CO adsorption | Test RMSE = 0.094 eV [14] | Hundreds to thousands of samples |

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) | Small-data settings (∼200 samples) | Test R² up to 0.98 [14] | Small, physics-informed datasets |

| Random Forest Regression | Monodentate adsorbates on ordered surfaces | MAE = 0.133 eV for CO adsorption [14] | Moderate dataset sizes |

| OCP equiformer_V2 MLFF | Adsorption energies across multiple facets | MAE = 0.16 eV vs DFT [2] | Pre-trained on OC20 database |

Experimental Protocols for Validating ML-Derived Descriptors

Protocol 1: Validating Novel Descriptor Concepts - The AED Framework

The development and validation of Adsorption Energy Distributions (AEDs) as comprehensive descriptors for CO₂ to methanol conversion catalysts exemplifies the rigorous experimental protocols required in ML-driven descriptor discovery [2] [17].

Workflow Implementation:

- Search Space Selection: 18 metallic elements with prior experimental relevance to CO₂ conversion were selected from the Open Catalyst 2020 (OC20) database to ensure prediction accuracy [2].

- Material Compilation: 216 stable phase forms (single metals and bimetallic alloys) were identified from the Materials Project database, with 22 excluded after failed DFT optimization, leaving 194 candidates [17].

- Adsorbate Selection: Key reaction intermediates (*H, *OH, *OCHO, *OCH₃) were identified from experimental literature on CO₂ thermocatalytic reduction [2].

- Surface Generation: Using fairchem repository tools from the Open Catalyst Project, surfaces with Miller indices ∈ {-2,-1,...,2} were created, with the most stable termination selected for each facet [2].

- High-Throughput Calculations: Over 877,000 adsorption energy calculations were performed using the OCP equiformer_V2 machine-learned force field, achieving a MAE of 0.16 eV against DFT benchmarks [2].

- Descriptor Validation: AEDs were treated as probability distributions, with similarity quantified using the Wasserstein distance metric and hierarchical clustering applied to identify catalysts with similar AED profiles to known high-performance materials [2] [17].

Experimental Outcome: This protocol identified promising candidate materials (ZnRh, ZnPt₃) with AED profiles similar to effective catalysts but potentially superior stability, demonstrating the power of ML-accelerated descriptor frameworks in practical catalyst discovery [17].

Protocol 2: Benchmarking Real-Space Chemical Descriptors with SchNet4AIM

The validation of explainable chemical artificial intelligence (XCAI) for real-space chemical descriptors addresses the critical challenge of interpretability in ML-driven chemistry [16] [18].

Workflow Implementation:

- Architecture Development: SchNet4AIM, a modified SchNet-based architecture, was designed to predict local one-body (atomic) and two-body (interatomic) real-space descriptors from quantum chemical topology (QTAIM/IQA) [16].

- Dataset Curation: A diverse collection of molecular systems was used to train the model on QTAIM descriptors including atomic charges (Q), localization (λ), and delocalization (δ) indices, plus IQA energetic terms [16].

- Model Training: The architecture was implemented in SchNetPack, with training focused on both global and local chemical properties through essential modifications to the standard SchNet approach [16].

- Performance Benchmarking: Prediction accuracy was validated against explicit QTAIM/IQA calculations, demonstrating the model's ability to break the computational bottleneck of these traditionally expensive computations [16].

- Chemical Insight Validation: The group delocalization indices, predicted by SchNet4AIM, were tested as reliable indicators of supramolecular binding events, confirming the retention of physical interpretability while achieving computational efficiency [16].

Experimental Outcome: SchNet4AIM provided physically rigorous atomistic predictions at negligible computational cost compared to explicit QTAIM/IQA calculations, enabling the tracking of quantum chemical descriptors along reaction pathways that were previously computationally prohibitive [16].

Diagram 1: ML-enhanced descriptor discovery workflow illustrates how machine learning accelerates and expands traditional catalyst design approaches.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for ML-Driven Descriptor Discovery

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open Catalyst Project (OC20/OC25) | Dataset | 7.8M+ DFT calculations across explicit solvent/ion environments for training ML models [19] | Open access |

| Materials Project | Database | Crystal structures and properties of known materials for search space definition [2] | Open access |

| fairchem/OCP MLFF | Software Tools | Pre-trained machine-learned force fields for rapid adsorption energy calculations [2] | Open source |

| SchNetPack | Software Framework | Implementation of SchNet4AIM for real-space chemical descriptor prediction [16] | Open source |

| Equivariant GNNs | Algorithm | Advanced neural networks for resolving chemical-motif similarity in complex systems [15] | Research code |

| CombinatorixPy | Software Package | Generation of mixture descriptors for complex chemical systems [20] | Open access |

| SISSO | Algorithm | Sure Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator for descriptor identification [13] | Research code |

| CatDRX | Framework | Reaction-conditioned generative model for catalyst design and optimization [21] | Research code |

Emerging Frontiers and Future Directions

The experimental validation of ML-driven descriptor discovery has revealed several promising frontiers. The Open Catalyst 2025 (OC25) dataset represents a significant advancement by incorporating explicit solvent and ion environments, enabling more realistic simulations of solid-liquid interfaces with state-of-the-art models achieving energy MAEs as low as 0.060 eV [19]. For electrochemical applications particularly, this explicit solvation capability addresses a critical limitation of earlier gas-phase datasets.

Explainable Chemical Artificial Intelligence (XCAI) has emerged as a crucial framework for maintaining interpretability while leveraging deep learning. By combining accurate ML with physically rigorous real-space descriptors, approaches like SchNet4AIM enable researchers to "give us insight not numbers" in accordance with Coulson's maxim, addressing the paradox where molecular properties can be accurately predicted but remain difficult to interpret [16] [18].

The development of composite descriptors that integrate multiple electronic and geometric factors represents another active research frontier. For instance, the ARSC descriptor decomposes factors affecting catalyst activity into Atomic property, Reactant, Synergistic, and Coordination effects, providing a one-dimensional analytic expression that predicts adsorption energies with accuracy comparable to ~50,000 DFT calculations while training on fewer than 4,500 data points [14].

Finally, generative AI models like CatDRX are expanding the descriptor discovery paradigm beyond prediction to actual creation of novel catalyst structures. By using reaction-conditioned variational autoencoders pre-trained on broad reaction databases, these models can generate potential catalysts with desired properties while considering critical reaction components often overlooked in earlier approaches [21].

The data-driven evolution of descriptor discovery through machine learning represents nothing short of a revolution in computational catalysis. The experimental validations comprehensively demonstrate that ML-enhanced approaches achieve comparable accuracy to traditional DFT-derived descriptors while offering orders-of-magnitude improvements in computational efficiency, broader transferability across material classes, and enhanced capacity to capture complex, non-linear relationships in catalytic systems.

While challenges remain in data quality, model interpretability, and generalizability, the integration of ML in descriptor discovery has fundamentally reshaped the catalyst design pipeline. The emergence of explainable chemical AI, composite descriptors, and generative models points toward an increasingly sophisticated and automated future for catalyst discovery—one where data-driven insights and physical principles synergistically guide the development of next-generation catalysts for energy conversion and sustainable chemical manufacturing.

The Critical Role of Descriptors in Modern Research

In computational materials science and drug discovery, descriptors are quantitative representations that capture key physical, chemical, or structural properties of a system, enabling the prediction of complex behaviors without exhaustive experimentation. The evolution from single-value descriptors to sophisticated, multi-faceted representations marks a significant paradigm shift, allowing researchers to navigate vast design spaces efficiently. Framed within the broader thesis of experimental validation for computational catalyst descriptors, this guide objectively compares the performance of three innovative classes of descriptors: Adsorption Energy Distributions (AEDs), Multi-Descriptor Linear Regression Models, and Chemical-Motif Fingerprints. These approaches are revolutionizing high-throughput screening and quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) modeling by offering a more holistic view of system characteristics, directly impacting the discovery of catalysts and therapeutic compounds.

The table below summarizes the core applications and validation benchmarks for these descriptor classes.

Table 1: Overview of Novel Descriptor Classes and Their Primary Applications

| Descriptor Class | Primary Field of Application | Key Represented Features | Typical Validation Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED) | Heterogeneous Catalysis [2] | Energetic landscape across material facets/sites [2] | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) vs. DFT: ~0.16 eV [2] |

| Multi-Descriptor Linear Regression | Catalysis Informatics [22] | Correlation between adsorption energies of different adsorbates [22] | Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), Mean Absolute Error [22] |

| Chemical-Motif Fingerprints | Drug Discovery & ADMET Prediction [23] [24] | Topological, physicochemical, & substructural features [23] | Predictive MAE, R² on Caco-2 permeability [23] |

Comparative Analysis of Novel Descriptors

This section provides a detailed, data-driven comparison of the three descriptor classes, outlining their core principles, experimental validation protocols, and performance against traditional alternatives.

Adsorption Energy Distributions (AEDs) for Catalyst Screening

Principle: The Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED) is a powerful descriptor developed to characterize complex, non-uniform catalytic surfaces. It moves beyond the traditional use of a single, minimum adsorption energy by aggregating the binding energies of key reaction intermediates across a multitude of surface facets and binding sites. This creates a statistical "fingerprint" of the material's energetic landscape, which is more representative of real-world catalysts that often exist as nanoparticles with diverse exposed facets [2].

Experimental Protocol for AED Construction:

- Search Space Selection: Identify a set of candidate materials, often from databases like the Materials Project, ensuring they consist of elements covered by the chosen machine-learning force field (e.g., the Open Catalyst Project) [2].

- Surface Generation: For each material, generate a variety of surface facets within a defined range of Miller indices (e.g., {-2, -1, 0, 1, 2}) and identify the most stable terminations [2].

- Adsorbate Configuration Engineering: Create surface-adsorbate configurations for the selected key intermediates (e.g., *H, *OH, *OCHO for CO₂ to methanol conversion) on the stable surfaces [2].

- Energy Calculation: Optimize the geometries and calculate the adsorption energies for all configurations. This is efficiently done using pre-trained machine-learned force fields (MLFFs) like the OCP equiformer_V2, which can accelerate calculations by a factor of 10⁴ or more compared to DFT while maintaining quantum mechanical accuracy [2].

- Data Cleaning & Validation: Clean the data by removing configurations that are computationally infeasible. Critically, validate the MLFF-predicted adsorption energies against explicit DFT calculations for a subset of materials (e.g., Pt, Zn, NiZn) to ensure a low MAE (e.g., ~0.16 eV) [2].

- Descriptor Construction & Analysis: Aggregate the validated adsorption energies for each material into a histogram or probability distribution, creating the AED. These distributions can then be compared using statistical metrics like the Wasserstein distance and analyzed with unsupervised learning (e.g., hierarchical clustering) to identify promising candidates with AEDs similar to known high-performing catalysts [2].

Table 2: Performance of the AED Workflow in Identifying CO₂ to Methanol Catalysts

| Workflow Step | Key Metric | Reported Outcome | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Calculation | Computational Speed-up | >10,000x vs. DFT [2] | Comparison of calculation time |

| Energy Validation | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | 0.16 eV overall [2] | MLFF vs. explicit DFT on Pt, Zn, NiZn |

| Candidate Identification | New Proposed Catalysts | ZnRh, ZnPt₃ [2] | Clustering analysis of AEDs |

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational workflow for constructing and applying AEDs.

Multi-Descriptor Linear Regression and Bayesian Framework

Principle: This approach extends the concept of simple linear scaling relations in catalysis. Instead of predicting the adsorption energy of a target species based on a single descriptor (e.g., the adsorption energy of a central atom), it leverages a multi-descriptor linear regression model. The model expresses the chemisorption energy of one adsorbate as a linear combination of the adsorption energies of other relevant species, thereby capturing more complex correlations in the data [22].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Compilation: Assemble a large dataset of computed adsorption energies for various adsorbates (e.g., C, H, N, O, CH, OH, NH) on a wide range of catalytic surfaces from databases like Catalysis-Hub.org [22].

- Model Construction: For a target adsorbate (e.g., *AHₓ), construct multiple candidate linear regression models using different subsets of other adsorbate energies as predictors:

ΔE_AHₓ = β₀ + β_AΔE_A + β_BΔE_B + ...[22]. - Bayesian Model Selection: Use the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) as model evidence to select the best-performing multi-descriptor linear model from the candidate pool, optimizing the bias-variance trade-off [22].

- Robust Prediction with Sparse Data: For small or sparse datasets, employ Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA). Instead of relying on a single model, BMA makes a robust prediction by averaging over a set of the best models, significantly reducing model uncertainty [22].

- Residual Learning with Gaussian Processes (Optional): For large datasets, further improve the prediction accuracy to levels comparable to standard DFT error (~0.1 eV) by using Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) to learn and predict the residual (error) of the selected linear model [22].

Table 3: Performance of Bayesian Multi-Descriptor Framework for Adsorption Energy Prediction

| Modeling Scenario | Core Methodology | Reported Advantage | Achieved Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large Dataset | Model Selection with BIC + Residual Learning with GPR [22] | Captures complex correlations beyond single descriptors [22] | Comparable to standard DFT error (~0.1 eV) [22] |

| Sparse/Small Dataset | Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA) [22] | Robust prediction by averaging multiple models, reducing uncertainty [22] | Improved over single-model conditioning [22] |

Chemical-Motif Fingerprints for Molecular Property Prediction

Principle: Chemical-motif fingerprints are numerical representations that encode the presence or absence of specific substructures, fragments, or physicochemical properties within a molecule. They are a cornerstone of traditional QSAR and modern machine learning in drug discovery. Recent advances involve systematically evaluating a wide array of these fingerprints and descriptors to build robust predictive models for properties like Caco-2 permeability, a key indicator of oral drug absorption [23] [24].

Experimental Protocol for ADMET Prediction:

- Dataset Curation: Collect a dataset of molecules with experimentally measured properties (e.g., Caco-2 Papp values). Use scaffold-based splitting to evaluate generalization to novel chemical structures [23].

- Multi-Representation Featurization: Compute a comprehensive set of molecular representations for each compound. This includes:

- Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) Modeling: Feed each feature set into an AutoML framework (e.g., AutoGluon). The AutoML system automates feature preprocessing, model selection (e.g., LightGBM, XGBoost, CatBoost), and hyperparameter optimization [23].

- Performance Evaluation & Interpretation: Evaluate models based on Mean Absolute Error (MAE), R², and RMSE. Use interpretability tools like SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) analysis to determine the most important features driving the predictions [23].

- Feature Optimization: Based on the importance analysis, select the top-ranked features and retrain the model with hyperparameter optimization via Bayesian methods to produce the final, best-performing model [23].

Performance Data: A systematic study (CaliciBoost) comparing eight molecular representations for Caco-2 permeability prediction found that PaDEL, Mordred, and RDKit descriptors were particularly effective when combined with an AutoML model. Crucially, the incorporation of 3D descriptors with PaDEL and Mordred led to a 15.73% reduction in MAE compared to using 2D features alone, highlighting the value of richer structural information [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The experimental protocols for developing and validating novel descriptors rely on a suite of computational tools and data resources. The following table details key components of the modern computational researcher's toolkit.

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Descriptor Research and Validation

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Descriptor Research |

|---|---|---|

| VASP [25] | Software Package | Performing first-principles DFT calculations for descriptor calculation (e.g., adsorption energies) and model validation. |

| Open Catalyst Project (OCP) [2] | Database & ML Models | Providing pre-trained MLFFs (e.g., equiformer_V2) for rapid, near-DFT-accurate energy calculations on massive scales. |

| Catalysis-Hub.org [22] | Database | Curated repository of adsorption energies and reaction pathways for training and testing predictive models. |

| Materials Project [2] | Database | Source of crystal structures and stability data for defining computational search spaces. |

| AutoGluon [23] | Software Library | AutoML framework for automating the process of building and optimizing ML models with diverse molecular features. |

| PaDEL, Mordred, RDKit [23] | Software Library | Generating comprehensive sets of 2D and 3D molecular descriptors and fingerprints from molecular structures. |

| SHAP [25] [23] | Software Library | Interpreting ML model outputs and quantifying the contribution of individual descriptors to a prediction. |

The transition from single, simplistic descriptors to complex, multi-dimensional representations like AEDs, multi-descriptor regression models, and optimized chemical-motif fingerprints marks a significant leap forward in computational materials science and drug discovery. The experimental data and protocols detailed in this guide demonstrate that these novel descriptors offer a more realistic, comprehensive, and information-rich picture of the systems under study.

AEDs effectively capture the intrinsic heterogeneity of real catalysts, enabling high-throughput screening with validated accuracy. The Bayesian multi-descriptor framework provides a robust statistical method to leverage correlations in adsorption data, reducing reliance on expensive quantum calculations. In drug discovery, systematic benchmarking of chemical-motif fingerprints combined with AutoML identifies optimal feature sets for predicting critical ADMET properties, with 3D structural information proving to be a key performance driver. Collectively, these approaches, underpinned by powerful computational tools and databases, create a validated and efficient pathway for accelerating the discovery of next-generation catalysts and therapeutics.

High-Throughput Frameworks for Accelerated Catalyst Discovery and Validation

The accurate computational screening of catalysts is pivotal for advancing sustainable energy technologies. While machine learning force fields (MLFFs) promise to deliver quantum-level accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost, their performance has historically been limited by the scarcity of training data that captures the complexity of real-world electrochemical environments. Prior Open Catalyst datasets (OC20 and OC22) provided foundational data for solid-gas interfaces but lacked the explicit solvent and ion representations critical for modeling electrocatalytic processes. The Open Catalyst 2025 (OC25) dataset represents a paradigm shift by introducing the largest and most diverse dataset for solid-liquid interfaces, enabling the development of MLFFs that realistically model electrocatalytic phenomena for energy storage and sustainable chemical production [26] [27] [19].

This advancement is particularly significant within the broader thesis of experimental validation of computational catalyst descriptors. While traditional MLFFs trained solely on density functional theory (DFT) data often inherit DFT's inaccuracies and fail to quantitatively match experimental observations [28], OC25's scale and environmental specificity provide a pathway toward models that bridge this fidelity gap. By encompassing explicit solvent environments, diverse ion types, and off-equilibrium configurations, OC25 establishes a new benchmark for developing experimentally-relevant MLFFs.

Dataset Comparison: OC25's Quantitative Leap Forward

OC25 constitutes a substantial expansion in scope and physical realism over its predecessors. The table below summarizes the key quantitative advances that make OC25 a transformative resource for the catalysis research community.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Open Catalyst Datasets

| Feature | OC20 | OC22 | OC25 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Interface | Solid-Gas | Solid-Gas | Solid-Liquid |

| Total Calculations | ~1.3 million | ~62,000 | 7.8 million |

| Key Environmental Features | Adsorbates on surfaces | Oxide surfaces, coverages | Explicit solvents, ions, solvation effects |

| Elemental Coverage | Extensive | Oxide materials | 88 elements |

| Unique Systems | Various surfaces & adsorbates | Oxide materials | ~1.5 million unique solvent environments |

| Average System Size | ~85 atoms | Information Missing | ~144 atoms |

| Critical Metrics | Adsorption energies | Adsorption on oxides | Energies, forces, and pseudo-solvation energy |

OC25's distinct value lies in its explicit treatment of the electrochemical interface. It incorporates eight common solvents (including water, methanol, acetonitrile) and nine inorganic ions (such as Li⁺, K⁺, SO₄²⁻), with ions present in approximately 50% of structures [26]. Furthermore, it introduces the pseudo-solvation energy metric (ΔE_solv), which quantifies the solvent's influence on adsorbate binding—a critical factor in electrocatalysis that was previously unaccounted for in large-scale benchmarks [26] [19]. The dataset was populated using off-equilibrium sampling from short ab initio molecular dynamics trajectories at 1000 K, ensuring a broad force-norm distribution that enhances ML model robustness [26].

Performance Benchmarks: OC25 vs. Established Baselines

The true measure of OC25's impact is evidenced by the performance of MLFFs trained on its data. The following table compares state-of-the-art models trained on OC25 against a previously established universal model, UMA-OC20.

Table 2: Model Performance Comparison on Energy, Force, and Solvation Metrics

| Model | Training Dataset | Energy MAE (eV) | Force MAE (eV/Å) | Solvation Energy MAE (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eSEN-S-cons. | OC25 | 0.105 | 0.015 | 0.045 |

| eSEN-M-d. | OC25 | 0.060 | 0.009 | 0.040 |

| UMA-S-1.1 | OC25 | 0.091 | 0.014 | 0.136 |

| UMA-OC20 (Reference) | OC20 | ~0.170 | ~0.027 | Not Applicable |

The results demonstrate that models trained on OC25 achieve a significant reduction in errors for energy and force predictions compared to the prior state-of-the-art, UMA-OC20 [26] [19]. For instance, the eSEN-M-d. model reduces force errors by more than 50% compared to UMA-OC20. More importantly, these models can now accurately predict the novel solvation energy metric, a capability essential for modeling in solution-phase environments. The best-performing models exhibit energy errors as low as 0.060 eV, force errors of 0.009 eV/Å, and solvation energy errors of 0.040 eV [26] [27]. This level of accuracy is a critical step toward performing reliable, large-scale molecular dynamics simulations of catalytic transformations at solid-liquid interfaces.

Experimental and Computational Protocols

DFT Methodology and Data Generation

The OC25 dataset was generated using rigorous, consistently applied Density Functional Theory protocols to ensure data quality and reliability [26]:

- Software and Functional: Calculations performed with VASP 6.3.2 using the RPBE exchange-correlation functional and Grimme's D3 zero-damping dispersion correction.

- Basis Set and Convergence: A 400 eV plane-wave cutoff with projector-augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials was employed. Electronic convergence was set to EDIFF = 10⁻⁴ eV for training data and a stricter 10⁻⁶ eV for validation/test sets.

- Sampling and Validation: Reciprocal density of 40 was used for k-point sampling. All calculations were non-spin-polarized. Force-drift filtering (total vector sum <1 eV/Å) was applied to enforce force-energy consistency.

ML Force Field Training Workflow

The development of MLFFs from the OC25 dataset follows a structured pipeline that integrates both computational and experimental validation. The workflow for creating and validating universal ML force fields involves multiple stages of data integration and training.

The training of baseline models for OC25 employed specific protocols to handle the dataset's complexity [26]:

- Model Architectures: Primarily Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) including eSEN (expressive smooth equivariant networks) and fine-tuned UMA (Universal Models for Atoms).

- Loss Function: A multi-task mean squared error loss balancing energy (E), force (F), and solvation energy (ΔE_solv) terms with typical weight ratios of 10:10:1.

- Training Details: Models were trained using the AdamW optimizer with decoupled weight decay for 40 epochs on NVIDIA H100 GPUs, with batch sizes of up to 76,800 atoms per step.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for OC25-Based Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| OC25 Dataset | Dataset | Training and benchmarking MLFFs for solid-liquid interfaces | Hosted on HuggingFace [19] |

| eSEN Models | Pre-trained MLFF | Baseline models for predicting energies, forces, and solvation effects | Available with the dataset [26] |

| AQCat25 | Supplementary Dataset | Spin-polarized and higher-fidelity DFT calculations for transfer learning | Integrated with OC25 [26] |

| FiLM Conditioning | Algorithmic Tool | Prevents catastrophic forgetting when training on multi-physics data | Recommended in training protocols [26] |

| DiffTRe Method | Algorithmic Tool | Enables training on experimental data with differentiable trajectory reweighting | For experimental fusion [28] |

The OC25 dataset represents a transformative advancement in the computational catalysis landscape, specifically addressing the critical need for large-scale data on solid-liquid interfaces that mirror experimental electrocatalytic conditions. By providing 7.8 million DFT calculations across explicit solvent and ion environments, OC25 enables the development of ML force fields with significantly improved accuracy for energy, force, and—most notably—solvation energy predictions.

This capability directly supports the broader thesis of experimental validation in computational catalyst descriptors. While challenges remain in fully reconciling computational predictions with experimental observables, OC25 provides an unprecedented foundation for this work. The integration of multi-physics data through techniques like FiLM conditioning and the availability of complementary datasets like AQCat25 further enhance the potential for developing MLFFs that are both computationally efficient and experimentally relevant. As these tools mature, they promise to accelerate the discovery of next-generation catalysts for energy storage and sustainable chemical production by providing researchers with increasingly reliable descriptors for catalyst performance.

The discovery and optimization of functional materials and catalysts are pivotal for advancing technologies in energy storage, drug development, and sustainable chemistry. Traditional empirical approaches, often reliant on trial and error, are increasingly being superseded by integrated workflows that combine computational prediction, data-driven modeling, and automated experimental validation. This guide objectively compares three dominant workflow methodologies based on their application, performance, and validation. The analysis is framed within a broader thesis on the experimental validation of computational descriptors, which are crucial for linking atomic-scale simulations to macroscopic material properties. We summarize quantitative performance data, provide detailed experimental protocols, and delineate the essential toolkit for researchers aiming to implement these synergistic approaches.

Comparative Analysis of Integrated Workflow Performance

The integration of Density Functional Theory (DFT), Machine Learning (ML), and High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) can be implemented through several distinct paradigms. The table below compares the core metrics, advantages, and limitations of three primary workflows: the Correction-Enhanced DFT/ML Workflow, the Pure ML Prediction Workflow, and the Automated HTE-Driven Workflow.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Integrated Workflow Strategies

| Workflow Strategy | Reported Accuracy/Performance | Computational/Experimental Efficiency | Key Supporting Evidence | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correction-Enhanced DFT/ML [29] | Periodic PBE DFT for 13C: RMSD improved with PBE0 correction.ML (ShiftML2) predictions showed minimal improvement with single-molecule correction. | DFT corrections are computationally efficient. ML model (ShiftML2) accelerates predictions by "orders of magnitude". | Validation against experimental NMR chemical shifts of amino acids, monosaccharides, and nucleosides [29]. | Limited transferability of corrections; ML model accuracy is constrained by its DFT training data. |

| Pure ML Prediction [30] [31] | R² = 0.922 for predicting HER free energy (ΔG_H) using Extremely Randomized Trees [31]. ML models link d-band features to adsorption energies [30]. | ML prediction time is 1/200,000th of traditional DFT methods [31]. Enables rapid screening of vast compositional spaces. | Prediction of 132 new HER catalysts; several validated with promising performance [31]. SHAP analysis identifies critical electronic descriptors [30]. | Dependent on quality and breadth of training data. May struggle with extrapolation to unseen material classes. |

| Automated HTE-Driven [32] | Enabled screening of ~2000 conditions per quarter, a 4x increase. Dosing deviations: <10% (sub-mg), <1% (>50 mg). | Automated solid dispensing reduced weighing time from 5-10 minutes/vial to <30 minutes for a full 96-well plate experiment. | Case study at AstraZeneca using CHRONECT XPR systems for catalyst and reagent dispensing in drug discovery campaigns [32]. | High initial capital investment. Requires significant software and hardware integration. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Workflows

Protocol 1: Correction-Enhanced DFT for NMR Crystallography

This protocol is designed to enhance the accuracy of NMR chemical shift predictions in molecular solids, as validated in studies of amino acid polymorphs [29].

- Periodic Calculation: Perform a full periodic DFT calculation (e.g., using the GIPAW method) on the crystal structure of interest using a GGA functional like PBE.

- Fragment Extraction: Extract a single molecule (or larger fragment) from the optimized periodic crystal structure.

- Dual-Level Single-Point Calculation: On the isolated fragment, perform two single-point NMR shielding calculations: a. At the same level as the periodic calculation (e.g., PBE). b. At a higher level of theory (e.g., using a hybrid functional like PBE0).

- Calculation of Correction: Compute the correction factor as the difference between the higher-level and lower-level shielding values (δhigh - δlow).

- Application of Correction: Apply this correction factor to the original periodic calculation results to obtain the final, refined chemical shifts.

- Experimental Validation: Compare the corrected chemical shifts with experimental solid-state NMR data to validate the improvement. For the referenced study, this protocol significantly reduced the RMSD for 13C chemical shifts [29].

Protocol 2: ML-Driven Discovery of Hydrogen Evolution Catalysts

This protocol outlines the development of an ML model for predicting hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) activity across diverse catalyst types [31].

- Data Curation: Compile a dataset of catalyst structures and their corresponding hydrogen adsorption free energy (ΔG_H). Public databases like Catalysis-hub can be sources, containing data for pure metals, intermetallic compounds, and perovskites [31].

- Feature Engineering: Calculate a minimal set of features (e.g., ~10) based on the atomic and electronic structure of the catalyst's active site. A key engineered feature is φ = Nd0²/ψ0, which correlates strongly with ΔG_H [31].

- Model Training and Selection: Train multiple ML models (e.g., Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Extremely Randomized Trees) on the feature dataset. Select the best-performing model based on metrics like R² and RMSE on a held-out test set.

- Model Interpretation: Use techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis to identify which features are most critical for the model's predictions, providing physical insights [30].

- High-Throughput Screening: Deploy the trained model to screen large databases (e.g., the Materials Project) for new candidate materials with predicted ΔG_H close to the ideal value of zero.

- Validation: Synthesize and electrochemically test the top-ranked candidate materials to validate their HER performance, confirming the ML predictions [31].

Protocol 3: Automated High-Throughput Experimentation for Catalysis

This protocol describes the implementation of an automated HTE platform for catalyst screening, as deployed in pharmaceutical research [32].

- Workflow Design: Define the experimental goal, such as optimizing a catalytic reaction or building a library of analogues. Design a 96-well plate layout to systematically vary parameters like catalyst, solvent, and building blocks.

- Automated Solid Dispensing: Use an automated powder-dosing system (e.g., CHRONECT XPR). The system is loaded with up to 32 different solid reagents, catalysts, and additives. Target masses for each vial in the array are programmed.

- Liquid Handling: Employ an automated liquid handler to dispense solvents and liquid reagents into the vials containing the pre-dosed solids.

- Reaction Execution: Transfer the 96-well plate to a controlled environment (e.g., a heated/cooled manifold inside an inert-atmosphere glovebox) for the reactions to proceed.

- Automated Analysis and Sampling: Integrate with analytical systems (e.g., UPLC/MS) for high-throughput analysis of reaction outcomes.

- Data Integration: Compile the results into a database for analysis. Use data analytics to identify "hits" and inform the next round of experimentation, creating a closed-loop optimization cycle where possible.

Workflow Visualization and Logical Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the synergistic interaction between DFT, Machine Learning, and High-Throughput Experimentation, forming a continuous cycle for accelerated materials discovery.

Diagram 1: Integrated Workflow for Material Discovery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of the integrated workflows relies on specific hardware, software, and data resources. The following table details key components of the modern researcher's toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Integrated Workflows

| Tool Name / Category | Function / Application | Specific Example / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Powder Dosing | Precisely dispenses solid reagents, catalysts, and additives at milligram scales for HTE. | CHRONECT XPR Workstation. Dispensing range: 1 mg to several grams; handles up to 32 different powders; dosing time: 10-60 seconds per component [32]. |

| Computational Catalysis Database | Provides curated datasets of calculated material properties for training ML models and benchmarking. | Catalysis-hub. Contains 10,855+ hydrogen adsorption free energy (ΔG_H) data points for various catalyst types [31]. |

| Electronic Structure Descriptors | Serves as features in ML models to predict catalytic activity and chemisorption properties. | d-band center, d-band filling, d-band width. Critical for predicting adsorption energies of C, O, N, and H in heterogeneous catalysis [30]. |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Builds predictive models for material properties and identifies key descriptors from complex data. | Extremely Randomized Trees (ETR), XGBoost, SHAP analysis. ETR model achieved R² = 0.922 for predicting ΔG_H using only 10 features [31] [30]. |

| Quantum Mechanical Software | Performs DFT and DFPT calculations to obtain structural, electronic, and response properties. | DFPT for IR, piezoelectric, and dielectric properties; GIPAW for NMR chemical shifts [33] [29]. |

The objective comparison presented in this guide demonstrates that no single workflow is universally superior; each excels in specific contexts. The Correction-Enhanced DFT/ML workflow provides high-fidelity predictions for well-defined systems like molecular crystals. The Pure ML Prediction workflow offers unparalleled speed for screening vast chemical spaces, provided robust training data exists. The Automated HTE-Driven workflow delivers tangible, validated results in complex application environments like drug discovery. The future of catalyst and material design lies in the intelligent integration of these approaches, creating closed-loop systems where computational predictions guide automated experiments, and experimental results continuously refine the computational models, dramatically accelerating the path from hypothesis to validated discovery.

The design of high-performance catalysts is a critical pursuit across the chemical and pharmaceutical industries, traditionally relying on costly, time-consuming experimental screening and intuition-driven approaches. Inverse design—which starts with desired catalytic properties and works backward to identify optimal structures—represents a paradigm shift in catalyst development. Among computational methods, generative artificial intelligence has emerged as a transformative technology for exploring the vast chemical space of potential catalysts. This guide focuses specifically on reaction-conditioned generative frameworks, a sophisticated class of models that design catalysts within the context of specific reaction environments [21].

These frameworks mark a significant evolution beyond earlier generative approaches that were limited to specific reaction classes or operated without considering critical reaction components. By conditioning the generation process on reaction-specific information—including reactants, products, reagents, and reaction conditions—these models demonstrate enhanced capability to identify novel, effective catalysts with practical relevance [21] [34]. This review provides an objective comparison of emerging reaction-conditioned platforms, examining their performance against traditional and contemporary alternatives, with particular emphasis on experimental validation and computational descriptors that bridge virtual design with practical application.

Comparative Analysis of Inverse Catalyst Design Platforms

Performance Benchmarking of Catalytic Activity Prediction

Quantitative evaluation of catalytic activity prediction reveals distinct performance patterns across platforms. The following table summarizes key metrics for reaction-conditioned frameworks alongside established alternatives:

Table 1: Performance comparison of catalytic activity prediction models across various datasets

| Model | Architecture | BH Dataset (RMSE) | SM Dataset (RMSE) | AH Dataset (RMSE) | CC Dataset (RMSE) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CatDRX [21] | Reaction-conditioned VAE | ~8.5 | ~7.2 | ~10.1 | ~15.3 | Competitive yield prediction, integrated generation & prediction |

| Inverse Ligand Design [34] | Transformer-based | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | High validity (64.7%), uniqueness (89.6%) |

| AEGAN [21] | Graph Neural Network | ~9.8 | ~8.1 | ~11.5 | ~14.2 | Multimodal (structure + sequence) |

| SCREEN [21] | Graph CNN + Contrastive Learning | ~10.2 | ~9.3 | ~12.8 | ~16.1 | Incorporates structural representations |

Performance analysis indicates that reaction-conditioned models achieve competitive results, particularly for yield prediction tasks where they frequently outperform specialized predictive models. The CatDRX framework demonstrates robust performance across BH, SM, and AH datasets, with RMSE values between 7.2-10.1, showcasing its generalization capabilities [21]. However, performance degradation on the CC dataset (RMSE: 15.3) highlights a critical limitation—these models struggle when applied to reactions with limited condition diversity or those residing outside the chemical space covered during pre-training [21].

For generative performance, validity and uniqueness metrics are equally crucial. The inverse ligand design model for vanadyl-based catalysts achieves 64.7% validity and 89.6% uniqueness, indicating strong capability to produce novel, chemically plausible structures [34]. Synthetic accessibility scores further support the practical feasibility of these generated ligands [34].

Experimental Validation and Performance Metrics

Beyond computational metrics, experimental validation provides the ultimate test for generative models. The following table summarizes experimental performance data for catalysts identified through generative approaches:

Table 2: Experimental validation of generative model outputs

| Generative Platform | Catalytic System | Key Experimental Metrics | Validation Approach | Experimental Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CatDRX [21] | Multiple reaction classes | Yield prediction accuracy | Computational chemistry validation | Competitive performance in downstream catalytic activity prediction |

| Inverse Ligand Design [34] | Vanadyl-based epoxidation catalysts | Reaction yield, synthetic accessibility | High synthetic accessibility scores | VOSO4 ligands consistent with high-yield reactions |

| CDVAE with Optimization [35] | CO2 reduction electrocatalysts | Faradaic efficiency | Synthesis & characterization of 5 alloy compositions | ~90% Faradaic efficiency for two generated alloys |

Experimental validation remains a significant challenge in the field, with many studies relying on computational validation or limited experimental verification. The CDVAE model exemplifies successful experimental translation, with generated alloy compositions actually synthesized and achieving Faradaic efficiencies of approximately 90% for CO2 reduction [35]. This highlights the potential for generative approaches to produce practically viable catalysts, not just computationally promising candidates.

Methodological Deep Dive: Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Core Architecture of Reaction-Conditioned Generative Models

Reaction-conditioned frameworks employ sophisticated architectures that jointly model catalyst structure and reaction context. The CatDRX implementation utilizes a conditional variational autoencoder (CVAE) with three specialized modules [21]: