Density Functional Theory in Catalyst Design: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to AI-Driven Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of Density Functional Theory (DFT) in rational catalyst design, a paradigm shift from traditional trial-and-error approaches.

Density Functional Theory in Catalyst Design: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to AI-Driven Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of Density Functional Theory (DFT) in rational catalyst design, a paradigm shift from traditional trial-and-error approaches. It covers foundational principles, including the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems and Kohn-Sham equations, and details methodological considerations for modeling both homogeneous and heterogeneous catalytic systems. The review further addresses key challenges such as functional selection, treatment of dispersion forces, and system size limitations, while exploring advanced topics like coverage effects and microkinetic modeling. Finally, it examines the growing integration of DFT with machine learning and generative AI for accelerated catalyst discovery and optimization, highlighting its implications for developing next-generation catalysts in energy and biomedical applications.

DFT Fundamentals: From Quantum Principles to Catalytic Insights

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has emerged as the most widely used computational method for electronic structure calculations in materials science and heterogeneous catalysis, representing a fundamental shift from wavefunction-based approaches to density-based formalism [1]. This transformation has proven particularly valuable in catalyst design research, where it provides an optimal compromise between accuracy and computational cost compared to semi-empirical methods or more accurate but computationally expensive wavefunction-theory-based approaches like coupled-cluster [1]. For researchers investigating catalytic mechanisms, DFT enables the determination of crucial properties including adsorption energies, equilibrium structures, transition state structures, and activation barriers for elementary reaction steps—parameters often difficult or impossible to obtain experimentally [2]. The theory's foundation rests upon two revolutionary mathematical theorems developed by Hohenberg and Kohn, and the practical implementation scheme introduced by Kohn and Sham, which together form the cornerstone of modern computational approaches to catalyst design and characterization.

Theoretical Foundations: The Hohenberg-Kohn Formalism

The Hohenberg-Kohn Theorems

The entire field of density functional theory is built upon two fundamental mathematical theorems proved by Hohenberg and Kohn [1]. The first Hohenberg-Kohn theorem establishes that "the ground-state electron density uniquely determines all properties, including energy and wavefunction, of the ground state" [1]. More formally, this theorem states that the external potential ( v{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r}) ) is uniquely determined by the ground state electron density ( \rho(\mathbf{r}) ), and since ( v{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r}) ) fixes the Hamiltonian, the entire system is uniquely determined by ( \rho(\mathbf{r}) ) [3]. This represents a significant conceptual simplification, as the electron density depends on only three spatial coordinates, compared to the 3N coordinates required to describe the many-electron wavefunction.

The second Hohenberg-Kohn theorem provides the variational principle for the density functional. It states that the ground-state energy can be obtained through the minimization of the energy functional ( E[\rho] ), and the density that minimizes this functional is the exact ground-state density [3]. This theorem can be expressed mathematically as:

where ( F[\rho] ) is a universal functional of the density that accounts for the kinetic energy and electron-electron interactions [3]. The minimization is performed under the constraint that the density integrates to the total number of electrons N [1].

Mathematical Formulation of the Theorems

Levy provided a particularly simple proof of the Hohenberg-Kohn theorem by defining a functional ( F[\rho] ) as:

[ F[\rho] = \min{\Psi \rightarrow \rho} \langle \Psi | \hat{T} + \hat{V}{ee} | \Psi \rangle ]

where the minimization is over all wavefunctions Ψ that yield the density Ï [3]. For a given external potential ( v_{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r}) ), the total energy functional is:

[ E{v{\text{ext}}}[\rho] = F[\rho] + \int v_{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r}) \rho(\mathbf{r}) d\mathbf{r} ]

The ground state energy is found by minimizing this expression over all N-electron densities Ï:

[ E0 = \min{\rho} E{v{\text{ext}}}[\rho] ]

This formal structure, while mathematically rigorous, does not immediately suggest practical computation methods, as the exact form of the universal functional F[Ï] remains unknown [3].

Table 1: Key Components of the Hohenberg-Kohn Formalism

| Component | Mathematical Expression | Physical Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Density | ( \rho(\mathbf{r}) = \sum_i N | \varphi_i(\mathbf{r}) | ^2 ) [4] | Probability density of electrons at position r |

| Universal Functional | ( F[\rho] = T[\rho] + V_{ee}[\rho] ) | Contains kinetic and electron-electron interaction terms | ||

| Energy Functional | ( E[\rho] = F[\rho] + \int v_{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r}) \rho(\mathbf{r}) d\mathbf{r} ) | Total energy as a functional of density | ||

| Variational Principle | ( E0 = \min{\rho} E{v{\text{ext}}}[\rho] ) | Foundation for finding ground state |

The Kohn-Sham Approach: From Theory to Practical Implementation

The Kohn-Sham Equations

While the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems established the theoretical foundation, the practical implementation of DFT became feasible through the approach introduced by Kohn and Sham in 1965 [4]. The key insight was to replace the original system of interacting electrons with a fictitious system of non-interacting particles that generate exactly the same electron density as the physical system of interacting particles [4]. This clever reformulation avoids the difficulty of directly dealing with the complex electron-electron interactions.

In the Kohn-Sham framework, the kinetic energy functional, which is challenging to express directly in terms of the density, is computed exactly for the non-interacting system using orbitals. The Kohn-Sham equations take the form of a Schrödinger-like equation for these non-interacting particles:

[ \left(-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\nabla^2 + v{\text{eff}}(\mathbf{r})\right)\varphii(\mathbf{r}) = \varepsiloni \varphii(\mathbf{r}) ]

where ( \varphii(\mathbf{r}) ) are the Kohn-Sham orbitals and ( \varepsiloni ) are the corresponding orbital energies [4]. The electron density is constructed from these orbitals:

[ \rho(\mathbf{r}) = \sumi^N |\varphii(\mathbf{r})|^2 ]

The effective potential ( v_{\text{eff}}(\mathbf{r}) ) is given by:

[ v{\text{eff}}(\mathbf{r}) = v{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r}) + e^2 \int \frac{\rho(\mathbf{r}')}{|\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}'|} d\mathbf{r}' + \frac{\delta E_{\text{xc}}[\rho]}{\delta \rho(\mathbf{r})} ]

where the terms represent the external potential, the Hartree (Coulomb) potential, and the exchange-correlation potential, respectively [4].

The Kohn-Sham Self-Consistent Cycle

The solution of the Kohn-Sham equations follows an iterative self-consistent procedure, which can be visualized as follows:

Figure 1: The Kohn-Sham self-consistent cycle for solving the single-particle equations. The process iterates until convergence in the electron density or total energy is achieved, typically requiring 10-100 iterations depending on the system and initial guess.

Total Energy Expression in Kohn-Sham Theory

In the Kohn-Sham approach, the total energy of a system is expressed as a functional of the charge density:

[ E[\rho] = Ts[\rho] + \int d\mathbf{r} \, v{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r}) \rho(\mathbf{r}) + E{\text{H}}[\rho] + E{\text{xc}}[\rho] ]

where:

- ( T_s[\rho] ) is the kinetic energy of the non-interacting Kohn-Sham system

- ( \int d\mathbf{r} \, v_{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r}) \rho(\mathbf{r}) ) is the interaction with the external potential

- ( E{\text{H}}[\rho] ) is the Hartree (Coulomb) energy: [ E{\text{H}}[\rho] = \frac{e^2}{2} \int d\mathbf{r} \int d\mathbf{r}' \, \frac{\rho(\mathbf{r}) \rho(\mathbf{r}')}{|\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}'|} ]

- ( E_{\text{xc}}[\rho] ) is the exchange-correlation energy, which contains all the many-body effects [4]

The relationship between the total energy and the Kohn-Sham orbital energies is given by:

[ E = \sumi^N \varepsiloni - E{\text{H}}[\rho] + E{\text{xc}}[\rho] - \int \frac{\delta E_{\text{xc}}[\rho]}{\delta \rho(\mathbf{r})} \rho(\mathbf{r}) \, d\mathbf{r} ]

It is important to note that the Kohn-Sham orbital energies ( \varepsilon_i ) generally have limited direct physical meaning, except in the context of Koopmans' theorem [4].

Exchange-Correlation Functionals: Approximations and Limitations

The Local Density Approximation and Beyond

The only unknown term in the Kohn-Sham energy expression is the exchange-correlation functional ( E_{\text{xc}}[\rho] ), which must be approximated in practice. The most basic approximation is the Local Density Approximation (LDA), which assumes that the exchange-correlation energy at a point r can be approximated by that of a homogeneous electron gas with the same density:

[ E{\text{xc}}^{\text{LDA}}[\rho] = \int \rho(\mathbf{r}) \varepsilon{\text{xc}}(\rho(\mathbf{r})) d\mathbf{r} ]

where ( \varepsilon_{\text{xc}}(\rho) ) is the exchange-correlation energy per particle of a homogeneous electron gas of density Ï [3]. While LDA works surprisingly well for systems where the density varies slowly, it has significant limitations for strongly correlated systems and tends to overbind molecules and solids [3].

To address the limitations of LDA, more sophisticated functionals have been developed, including Generalized Gradient Approximations (GGA) that incorporate the gradient of the density:

[ E_{\text{xc}}^{\text{GGA}}[\rho] = \int f(\rho(\mathbf{r}), \nabla \rho(\mathbf{r})) d\mathbf{r} ]

Popular GGA functionals include the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional, which is widely used in catalytic applications [2]. Further improvements include meta-GGA functionals that incorporate the kinetic energy density, and hybrid functionals that mix a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange.

Table 2: Common Exchange-Correlation Functionals in Catalysis Research

| Functional Type | Examples | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDA | SVWN | Simple, relatively fast | Overbinding, poor for molecules |

| GGA | PBE, PW91 | Better for molecules, widely used | Underestimates barriers, band gaps |

| Meta-GGA | SCAN, TPSS | Improved for diverse bonding | Higher computational cost |

| Hybrid | B3LYP, HSE06 | Better band gaps, barriers | High computational cost |

| Van der Waals | vdW-DF, DFT-D | Accounts for dispersion | Parameterization dependencies |

Limitations of Current Approximations

Despite the remarkable success of DFT, important limitations persist in its practical applications. For strongly correlated systems where an independent particle picture breaks down, such as transition metal oxides (e.g., FeO, MnO, NiO), standard functionals like LDA and GGA are very inaccurate [3]. These functionals also struggle with describing van der Waals bonding and provide only a poor description of hydrogen bonding, which is essential for most biochemical applications [3].

In the context of catalysis, standard GGA functionals tend to underestimate reaction barriers, band gaps of materials, and the energies of dissociating molecular ions [2]. These limitations have prompted the development of various correction schemes, including the DFT+U approach for strongly correlated systems [2] and specialized van der Waals functionals for dispersion interactions [2].

Computational Protocols for Catalytic Applications

Model Selection for Heterogeneous Catalysis

The reliability of DFT calculations in catalysis research depends critically on the appropriate selection of computational models. For heterogeneous catalysis, the most common approach involves using slab models to represent catalyst surfaces [2]. These models should:

- Include appropriate crystal facets based on the morphology of the real catalytic nanoparticles

- Be sufficiently thick to properly describe surface properties (typically 3-5 atomic layers)

- Use adequate vacuum separation between periodic images (typically 10-15 Ã…)

- Employ appropriate k-point sampling for Brillouin zone integration

For supported metal catalysts, model development becomes more challenging. Recent approaches include single-atom catalysts (SACs) models, where metal atoms are anchored to support surfaces [1], and models that attempt to capture metal-support interactions [5].

Calculation of Catalytic Properties

The application of DFT in catalysis research typically focuses on calculating several key properties:

Adsorption energies are calculated as: [ E{\text{ads}} = E{\text{surface+adsorbate}} - E{\text{surface}} - E{\text{adsorbate}} ] where more negative values indicate stronger adsorption [1].

Reaction energy barriers are determined through transition state search methods such as the nudged elastic band (NEB) method or dimer method, followed by frequency calculations to confirm the transition state (exactly one imaginary frequency) [1].

Electronic structure descriptors like the d-band center have been proved as promising descriptors for rationalizing electrocatalytic activity [1]. The d-band center model provides an approximate description of bond formation at transition metal surfaces, showing that adsorption becomes stronger with the upshift of the d-band center toward the Fermi level [2].

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Approaches for DFT in Catalysis Research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Application in Catalysis Research |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Software | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, Gaussian, CP2K | Electronic structure calculations with periodic or cluster models |

| Transition State Search | Nudged Elastic Band (NEB), Dimer Method | Location of transition states and reaction pathways |

| Basis Sets | Plane Waves, Atomic Orbitals, PAW Pseudopotentials | Representation of electronic wavefunctions |

| Analysis Tools | Bader Analysis, DOS, PDOS, Charge Analysis | Electronic structure analysis and descriptor extraction |

| Microkinetic Modeling | CATKIN, KMOS | Conversion of DFT energies to reaction rates |

Application to Catalyst Design: Case Studies and Protocols

Protocol: DFT Calculation of Adsorption Energies

Purpose: To determine the binding strength of molecules on catalyst surfaces, a crucial parameter in catalytic activity assessment.

Procedure:

- Geometry Optimization

- Build the clean surface model (slab) with appropriate Miller indices

- Fully optimize the slab structure until forces are below 0.01 eV/Ã…

- Place the adsorbate molecule at various plausible sites on the surface

- Optimize the adsorbate-surface system until convergence

Single-Point Energy Calculations

- Calculate the total energy of the optimized surface-adsorbate system

- Calculate the total energy of the clean surface with the same geometry

- Calculate the total energy of the isolated gas-phase molecule

Energy Analysis

- Compute adsorption energy using the formula above

- Perform Bader charge analysis to understand electronic redistribution

- Analyze electronic density of states to identify interaction mechanisms

Validation: Compare with experimental temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) data when available.

Case Study: Charge-Modulated Switchable CO2 Capture

DFT calculations have enabled the formulation of novel catalytic and capture strategies, such as the charge-modulated switchable CO2 capture using boron nitride (BN) nanosheets and nanotubes [1]. This approach, proposed based on DFT studies, demonstrates that:

- CO2 molecules weakly adsorb on neutral BN

- When excess electrons are injected, CO2 adsorption is dramatically enhanced

- As excess electrons are removed, adsorbed CO2 is easily released

- Charged BN nanomaterials show high selectivity in separating CO2 from gas mixtures like CO2/CH4 and CO2/H2 [1]

Subsequent DFT investigations explored conductive borophene nanosheets as a promising candidate for this application, overcoming the high band gap challenge of BN materials [1]. This case study illustrates how DFT calculations can guide the exploration of novel sorbent materials with higher selectivity, capacity, and ideal thermodynamics.

Protocol: Reaction Mechanism and Barrier Calculations

Purpose: To determine the complete reaction pathway and rate-determining steps for catalytic reactions.

Procedure:

- Reactant and Product State Identification

- Optimize geometry of initial reactant state (RS)

- Optimize geometry of final product state (PS)

- Confirm both are local minima through frequency calculations

Transition State Search

- Use NEB method to generate initial guess of reaction path

- Refine the transition state using climbing-image NEB or dimer method

- Verify transition state through frequency calculation (exactly one imaginary frequency)

Reaction Pathway Analysis

- Calculate reaction energy: ΔE = E(PS) - E(RS)

- Calculate activation barrier: Ea = E(TS) - E(RS)

- Perform electronic structure analysis along the reaction path

Microkinetic Modeling (Optional)

- Convert DFT energies to free energies using thermodynamic corrections

- Compute rate constants using transition state theory

- Solve kinetic equations to obtain turnover frequencies

The Hohenberg-Kohn theorems and Kohn-Sham approach together form the fundamental theoretical foundation underlying modern computational catalysis research. While the formal exactness of DFT is guaranteed by the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, the practical success of the method relies heavily on the Kohn-Sham scheme and the quality of approximate exchange-correlation functionals.

Despite limitations in describing strongly correlated systems and dispersion interactions, DFT has become an indispensable tool in catalyst design, enabling researchers to understand catalytic mechanisms at atomic resolution and screen potential catalyst materials without labor-intensive synthetic procedures [5]. Current research focuses on developing more accurate functionals, improving methods for modeling complex catalytic environments, and integrating DFT with machine learning approaches for accelerated catalyst discovery.

As computational power continues to grow and theoretical methods advance, DFT calculations are expected to play an increasingly important role in the rational design of catalysts for sustainable energy applications, environmental protection, and chemical synthesis, bridging the gap between theoretical chemistry and practical catalyst development.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a computational quantum mechanical modelling method widely used in physics, chemistry, and materials science to investigate the electronic structure of many-body systems, particularly atoms, molecules, and condensed phases [6]. By using functionals (functions of functions) that depend on the spatially dependent electron density, DFT provides a versatile framework for determining the properties of many-electron systems while avoiding the computational intractability of direct solutions to the many-electron Schrödinger equation [6]. This approach has become particularly valuable in catalyst design research, where understanding electronic behavior at the quantum level enables rational design of catalytic materials.

The foundational principle of DFT is that all ground-state properties of a quantum system, including the energy, are uniquely determined by the electron density distribution n(r) [6]. This revolutionary concept reduces the problem of solving for a wavefunction dependent on 3N spatial coordinates (for N electrons) to one of finding a density dependent on only three coordinates, dramatically simplifying computational demands while maintaining quantum mechanical accuracy in principle.

Theoretical Foundations

The Electronic Structure Problem

In quantum chemistry, the electronic structure of a system with N electrons is described by a wavefunction Ψ(r1, …, rN) that satisfies the many-electron time-independent Schrödinger equation [6]:

ĤΨ = [T̂ + V̂ + Û]Ψ = EΨ

where T̂ represents the kinetic energy of the electrons, V̂ represents the external potential (typically electron-nucleus interactions), and Û represents the electron-electron interaction energy [6]. The complexity of solving this equation grows exponentially with the number of electrons, making direct solutions impossible for all but the smallest systems.

Traditional wavefunction-based methods, such as Hartree-Fock and post-Hartree-Fock approaches, attempt to approximate the many-electron wavefunction directly, but become computationally prohibitive for larger systems relevant to catalyst design [6].

The Hohenberg-Kohn Theorems

The theoretical foundation of DFT rests on two fundamental theorems proved by Hohenberg and Kohn [6]:

- Theorem I: The ground-state electron density n(r) uniquely determines the external potential V(r) (up to an additive constant), and thus all properties of the system.

- Theorem II: A universal functional for the energy E[n] in terms of the density n(r) exists, and the exact ground-state density minimizes this functional.

These theorems establish that the electron density alone is sufficient to determine all ground-state properties, without need for the full many-electron wavefunction [6]. For catalyst design, this means that relatively simple density-based calculations can, in principle, predict complex catalytic behaviors.

The Kohn-Sham Approach

Kohn and Sham introduced a practical computational scheme by mapping the interacting system of electrons onto a fictitious system of non-interacting electrons with the same density [6]. This approach leads to the Kohn-Sham equations:

(-½∇² + Veff(r))ψi(r) = εiψi(r)

where Veff(r) = Vext(r) + ∫(n(r')/|r-r'|)d³r' + V_xc(r)

The Kohn-Sham equations must be solved self-consistently because the effective potential Veff depends on the electron density, which in turn depends on the Kohn-Sham orbitals ψi [7]. This formulation decomposes the total energy into manageable components:

Etot^DFT = Tnon-int + Eestat + Exc + E_nn

where Tnon-int is the kinetic energy of the non-interacting system, Eestat includes electron-nucleus attraction and classical electron-electron repulsion, Exc is the exchange-correlation energy, and Enn is the nucleus-nucleus repulsion [8].

Exchange-Correlation Functionals

The Exchange-Correlation Energy

The exchange-correlation energy Exc contains all quantum mechanical effects not captured by the other terms, including exchange (due to the antisymmetry of the wavefunction) and correlation (due to electron-electron interactions beyond mean-field approximation) [8]. The exact form of Exc is unknown, and developing accurate approximations constitutes the central challenge in DFT development.

For catalytic applications, the treatment of exchange and correlation is particularly important for describing adsorption energies, reaction barriers, and electronic properties of transition metal complexes—all critical factors in catalyst performance.

Hierarchy of Functionals

Table 1: Classification of Exchange-Correlation Functionals

| Functional Type | Dependence | Examples | Computational Cost | Typical Applications in Catalysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Density Approximation (LDA) | Local density n(r) | Slater+Perdew-Zunger [7] | Low | Baseline calculations, homogeneous systems |

| Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) | Density n(r) and its gradient ∇n(r) | PBE [7], PW91 [9] | Low-medium | Structural optimization, surface adsorption |

| Meta-GGA | Density, gradient, and kinetic energy density Ï„(r) | SCAN [7], MCML [8] | Medium | Reaction energies, simultaneous bulk/surface properties |

| Hybrid | Mix of HF exchange with semi-local functionals | B3LYP [9], HSE06 [7] | High | Molecular systems, band gaps, reaction barriers |

| Machine Learning | Learned from high-level data | DM21 [8], MCML [8] | Varies | Specialized properties, uncertainty quantification |

Local Density Approximation (LDA)

LDA is the simplest approximation, where the exchange-correlation energy at each point in space is that of a homogeneous electron gas with the same density [10]:

Exc^LDA[n] = ∫ n(r) εxc(n(r)) d³r

The exchange component has an exact analytical form: E_x^LDA[n] = -¾(3/π)^{1/3} ∫ n(r)^{4/3} d³r [10]. The correlation component is derived from quantum Monte Carlo simulations of the homogeneous electron gas [10]. While LDA provides a reasonable starting point, it tends to overbind, making bond lengths too short and binding energies too large—a significant limitation for accurate catalyst modeling.

Generalized Gradient Approximations (GGA)

GGA functionals incorporate the gradient of the electron density to account for inhomogeneities in real systems [7]:

Exc^GGA[n] = ∫ εxc(n(r), ∇n(r)) d³r

The PBE (Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof) functional is widely used in solid-state physics and catalysis research for geometry optimization [7]. GGAs generally improve upon LDA for molecular properties and surface energies, making them suitable for preliminary catalyst screening.

Meta-GGA Functionals

Meta-GGAs include additional dependence on the kinetic energy density τ(r) = Σi^N (1/2)|∇ψi(r)|², enabling detection of local bonding character [8]:

Exc^MGGA[n] = ∫ εxc(n(r), ∇n(r), ∇²n(r), τ(r)) d³r

Functionals like SCAN and machine-learned functionals such as MCML can simultaneously describe diverse materials properties with good accuracy [8] [7]. For catalyst design, meta-GGAs offer improved performance for both reaction energies and lattice properties without the computational cost of hybrid functionals.

Hybrid Functionals

Hybrid functionals mix a fraction of exact Hartree-Fock exchange with semi-local DFT exchange [7]:

Exc^hybrid = α Ex^HF + (1-α) Ex^SL + Ec^SL

The HSE06 functional is particularly popular for periodic systems in catalysis research because it screens the long-range HF exchange, improving computational efficiency [7]. Hybrid functionals typically provide better band gaps and reaction barriers but at significantly higher computational cost.

Machine-Learned Functionals

Recent advances include machine-learning techniques to develop functionals trained on high-level theoretical data and experimental benchmarks [8]. For example, the MCML functional focuses on optimizing the semi-local exchange in a meta-GGA while keeping correlation in GGA form, showing improved performance for surface chemistry [8]. These approaches can also provide uncertainty quantification through Bayesian ensemble methods [8].

Specialized Corrections

van der Waals Corrections

Standard semi-local functionals poorly describe dispersion interactions (van der Waals forces), which are crucial for molecular adsorption on catalyst surfaces [6] [8]. Non-local van der Waals functionals like VV10 and optimized functionals like VCML-rVV10 incorporate these effects explicitly [8].

DFT+U

For strongly correlated systems (e.g., transition metal oxides with localized d- or f-states), the DFT+U approach adds an on-site Coulomb repulsion term to mitigate self-interaction errors [8] [7]. Machine learning approaches now enable site- and reaction coordinate-dependent U parameters for surface reactions [8].

Computational Protocols for Catalyst Design

Workflow for Catalytic Property Prediction

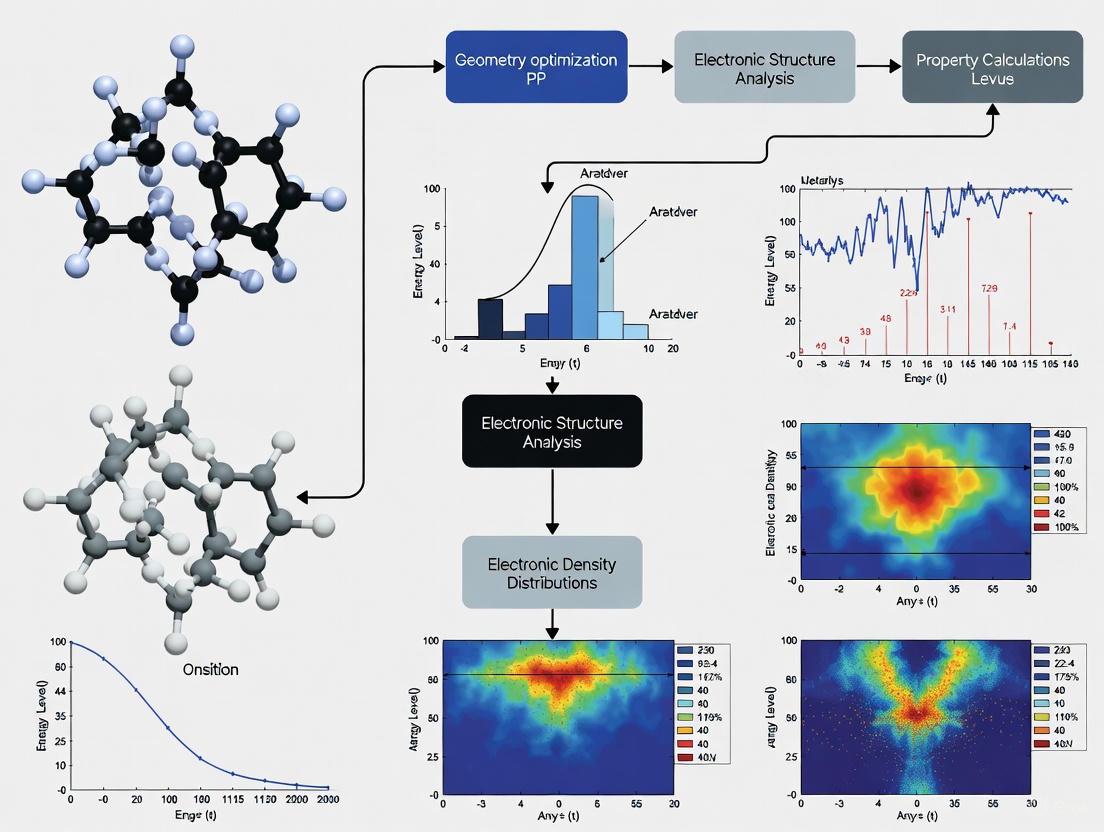

The following diagram illustrates a standardized computational workflow for evaluating catalytic properties using DFT:

Diagram 1: DFT workflow for catalytic property prediction.

Protocol: Surface Adsorption Energy Calculation

Objective: Determine the adsorption energy of a reaction intermediate on a catalytic surface.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Surface Model Preparation:

- Select appropriate Miller indices for the catalytic surface (e.g., Pt(111) for FCC metals).

- Create a slab model with sufficient thickness (typically 3-5 atomic layers).

- Add vacuum layer (≥15 Å) to separate periodic images in the z-direction.

- Fix bottom 1-2 layers at bulk positions while relaxing top layers.

Bulk Optimization:

- Perform full geometry optimization of the bulk catalyst material.

- Use PBE functional with high k-point mesh (e.g., 15×15×15 for metals).

- Converge forces to <0.01 eV/Ã… and energy to <10â»âµ eV/atom.

- Record the optimized lattice parameters for surface model construction.

Clean Surface Optimization:

- Optimize the slab structure using the same functional.

- Use k-point mesh appropriate for surface calculations (e.g., 5×5×1).

- Converge forces on relaxed atoms to <0.02 eV/Ã….

- Calculate the total energy E_slab.

Adsorbate Optimization:

- Optimize the gas-phase adsorbate molecule in a large box (e.g., 15×15×15 ų).

- Calculate the total energy Eadsorbategas.

Adsorption Complex Optimization:

- Place the adsorbate at appropriate surface sites (top, bridge, hollow).

- Optimize the full adsorption complex.

- Converge forces to <0.02 eV/Ã….

- Calculate the total energy E_slab+adsorbate.

Adsorption Energy Calculation:

- Compute adsorption energy: Eads = Eslab+adsorbate - Eslab - Eadsorbate_gas

- Include zero-point energy corrections from vibrational frequency calculations if required.

Functional Selection Guide:

- For initial screening: PBE GGA functional

- For accurate adsorption energies: meta-GGA (SCAN) or hybrid (HSE06)

- For dispersion-dominated adsorption: PBE+vdW or VCML-rVV10

Protocol: Catalytic Reaction Barrier Calculation

Objective: Determine the activation energy for an elementary reaction step on a catalyst surface.

Methodology:

Initial and Final State Optimization:

- Optimize reactant and product states using the protocol in Section 4.2.

- Confirm local energy minima through vibrational frequency analysis (no imaginary frequencies).

Transition State Search:

- Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) Method: Place 5-8 images along the reaction path and optimize until the maximum force on the climbing image is <0.05 eV/Ã….

- Dimer Method: Use for systems with known initial state but unknown reaction path.

- Verify transition state through single imaginary frequency corresponding to the reaction coordinate.

Energy Profile Construction:

- Calculate the electronic energy difference between transition state and initial state.

- Include zero-point energy corrections from vibrational analysis.

- For finite-temperature predictions, compute Gibbs free energy corrections.

Functional Considerations: Hybrid functionals (HSE06) are recommended for accurate barrier heights, though meta-GGAs provide reasonable compromise between cost and accuracy.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for DFT in Catalyst Design

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Catalyst Research |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Software Packages | VASP [7], Quantum ESPRESSO, CASTEP [10] | Core computational engines for solving Kohn-Sham equations and computing electronic properties |

| Visualization & Analysis | VESTA, JMOL, VMD | Structure building, charge density visualization, and computational result analysis |

| Workflow Management | ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment), AiiDA | Automation of complex computational workflows and data management |

| Specialized Functionals | PBE [7], HSE06 [7], SCAN [7], MCML [8] | Exchange-correlation approximations tailored for specific catalytic properties |

| Benchmark Databases | CatApp, NOMAD, Materials Project | Reference data for validation and high-throughput screening of candidate materials |

| Biotin-C1-PEG3-C3-amine TFA | Biotin-C1-PEG3-C3-amine TFA, MF:C22H38F3N3O7S, MW:545.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| pH-Low Insertion Peptide | pH-Low Insertion Peptide (pHLIP)|Research Use Only | pH-Low Insertion Peptide (pHLIP) targets acidic microenvironments for cancer research and drug delivery. This product is for Research Use Only and not for human use. |

Performance Assessment of Functionals

Table 3: Functional Performance for Catalytically Relevant Properties

| Functional | Binding Energies (MAE) | Reaction Barriers (MAE) | Lattice Constants (MAE) | Band Gaps (MAE) | Computational Cost Relative to LDA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDA | 1.5-2.0 eV (overbinding) [10] | Typically underestimated [6] | 1-2% underestimate [10] | Severe underestimate [6] | 1.0× |

| PBE (GGA) | 0.2-0.3 eV [9] | 0.1-0.2 eV [9] | ~1% overestimate [7] | Underestimated [8] | 1.2× |

| SCAN (meta-GGA) | 0.1-0.15 eV [7] | 0.08-0.15 eV | <0.5% [7] | Improved but still low [8] | 1.5× |

| HSE06 (hybrid) | 0.1-0.2 eV | 0.05-0.1 eV | ~0.5% [7] | Good agreement [8] | 10-100× |

| MCML (machine-learned) | 0.05-0.1 eV [8] | Not reported | <0.5% [8] | Varies [8] | 1.5-2.0× |

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its widespread success, DFT faces several challenges in catalyst design applications. The band gap problem—systematic underestimation of semiconductor and insulator band gaps—affects predictions of electronic properties in oxide catalysts and photocatalysts [6] [8]. Treatment of strongly correlated systems (e.g., transition metal oxides with localized d- or f-states) remains difficult without empirical corrections like DFT+U [8]. Accurate description of van der Waals interactions is crucial for molecular adsorption but requires specialized functionals [6] [8]. The quantitative prediction of reaction barriers is particularly sensitive to the exchange-correlation functional [6].

Future developments focus on machine-learned functionals that incorporate physical constraints while training on high-quality data [8], more sophisticated beyond-DFT methods for strongly correlated systems [8], and efficient implementations that make higher-level functionals accessible for routine catalytic screening [11]. For catalyst designers, these advances promise increasingly accurate predictions of catalytic activity, selectivity, and stability from first principles.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) stands as a cornerstone computational methodology in modern catalytic research, enabling scientists to probe the quantum mechanical foundations of catalytic processes at the atomic scale. This approach revolutionized computational materials science by reformulating the intractable many-electron Schrödinger equation into a tractable problem based on the electron density, a function of just three spatial coordinates [6]. For researchers in catalyst design, DFT provides a powerful virtual laboratory where catalytic systems can be investigated with unprecedented detail, from reaction energetics and electronic structure to surface dynamics and charge transfer processes.

The fundamental theorem underlying DFT states that all ground-state properties of a many-electron system, including energy and electronic structure, are uniquely determined by its electron density distribution Ï(r) [6] [12]. This conceptual breakthrough, pioneered by Hohenberg, Kohn, and Sham, forms the theoretical foundation upon which modern computational catalysis is built. The practical implementation of DFT occurs through the Kohn-Sham equations, which map the interacting system of electrons onto a fictitious system of non-interacting electrons moving within an effective potential [6] [11]. This effective potential incorporates the external potential from atomic nuclei, the classical Coulomb repulsion between electrons, and the quantum mechanical exchange-correlation effects that represent the most significant challenge in DFT approximations.

In contemporary catalyst design, DFT serves as an indispensable tool that bridges theoretical chemistry and materials engineering. By calculating critical parameters that are often difficult to measure experimentally, DFT provides fundamental insights into reaction mechanisms, active site characterization, and catalyst stability. The following sections detail the specific calculable properties in DFT, present structured protocols for their implementation, and demonstrate how these computations integrate into a comprehensive catalyst design workflow.

Calculable Properties in DFT for Catalysis

DFT enables the calculation of three fundamental categories of properties essential for understanding and predicting catalytic performance: energy landscapes, structural characteristics, and electronic properties. These computations provide the quantitative foundation for rational catalyst design.

Energy Calculations

Energy calculations form the predictive backbone of catalytic DFT studies, enabling the thermodynamic and kinetic assessment of reaction pathways.

Table 1: Energy Calculations in Catalytic DFT Studies

| Property | Catalytic Application | Key Outputs | Interpretation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption Energies | Active site characterization, binding strength assessment | ΔEads (eV) | More negative values indicate stronger adsorption; Sabatier principle optimization |

| Reaction Energies | Thermodynamic feasibility of catalytic steps | ΔErxn (eV) | Exothermic (negative) vs. endothermic (positive) processes |

| Activation Barriers | Kinetic profiling, rate-determining step identification | Ea (eV) | Higher barriers indicate slower elementary steps; determines turnover frequency |

| Transition States | Reaction mechanism elucidation | Energy saddle point (eV), Imaginary frequency | Confirms connection between reactants and products along minimum energy path |

| Free Energy Landscapes | Potential-dependent electroanalysis (GC-DFT) | ΔG (eV) at applied potential | Determines thermodynamic overpotentials; identifies potential-dependent selectivity |

For electrochemical processes such as CO2 reduction, grand-canonical DFT (GC-DFT) extends standard energy calculations to incorporate electrode potential explicitly. This approach has revealed key descriptors such as CH* binding energy as the governing factor for acetate selectivity in CO electroreduction, enabling the AI-guided discovery of Cu/Pd and Cu/Ag catalysts with Faradaic efficiencies of 50% and 47%, respectively [13]. Similarly, DFT-based screening of single-atom catalysts (SACs) identified Pd@C5N as a superior CO2-to-CH4 catalyst with a limiting potential of just 0.42 V [14].

Structural Properties

Structural computations provide atomic-level insights into catalyst morphology, stability, and active site configuration.

Table 2: Structural Properties in Catalytic DFT Studies

| Property | Catalytic Application | Methodological Approach | Information Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equilibrium Geometry | Stable catalyst configuration | Ionic relaxation, lattice optimization | Ground-state atomic coordinates, lattice parameters |

| Surface Energies | Catalyst stability, morphology prediction | Slab model energy vs. bulk reference | Wulff shape construction; relative stability of crystal facets |

| Defect Formation Energies | Point defect, vacancy, dopant stability | Energy comparison with perfect lattice | Dominant defect types under synthesis conditions |

| Vibrational Frequencies | Spectroscopic fingerprinting (IR, Raman) | Phonon dispersion, molecular vibrations | Identification of adsorbed species, thermal properties |

| Charge Density Distribution | Bonding characterization, active site localization | 3D spatial visualization | Ionic/covalent/metallic bonding analysis; polarization effects |

Structural optimization through force minimization allows DFT to predict stable catalyst configurations, including surface reconstructions and defect structures that often govern catalytic activity. For example, DFT investigations of Y2CF2 monolayers confirmed their dynamic and thermodynamic stability while revealing semimetallic behavior and favorable metal atom diffusion barriers (6.8-28.6 eV), suggesting potential applications in battery technologies and electrocatalysis [15]. Elastic constant calculations further provide mechanical property assessment through energy changes induced by small atomic displacements, yielding Young's modulus, bulk modulus, and shear modulus critical for evaluating catalyst durability under operating conditions [12].

Electronic Properties

Electronic structure calculations reveal the fundamental origins of catalytic activity through quantum mechanical analysis of electron behavior.

Band Structure: DFT-calculated band structures provide critical insights into conductive behavior by mapping electron energy versus momentum relationships. The bandgap width directly determines whether a material exhibits metallic, semiconducting, or insulating characteristics, which governs charge transport in electrocatalysis [12] [16]. For instance, DFT revealed that indium-doped MoS2 possesses a dramatically reduced bandgap (0.02 eV) compared to pure MoS2 (2.09 eV), explaining its enhanced conductivity and catalytic performance [16]. Functional selection significantly impacts accuracy, with LDA and GGA typically underestimating bandgaps by ~40%, while hybrid functionals like HSE06 provide experimental agreement.

Density of States (DOS): The total and projected density of states offers a energy-resolved picture of electron availability. Integrated DOS near the Fermi level estimates effective carrier concentration, while projected DOS (PDOS) decomposes contributions from specific atomic orbitals (e.g., transition metal d-states or non-metal p-states) [16]. Orbital hybridization, indicated by overlapping PDOS peaks, reveals bonding characteristics critical to catalytic function, such as sp2 hybridization in graphene facilitating conjugated π-bonds that promote electron localization [16].

Work Function (WF): Surface-dependent WF calculations quantify electron confinement strength, with higher values indicating tighter electron binding. WF differences between crystal facets or materials drive interfacial polarization in heterostructures, a crucial energy dissipation mechanism in catalytic systems [16]. Strategic interfacial engineering leverages substantial WF disparities to enhance electron localization at heterojunctions, improving charge separation and catalytic activity.

Computational Protocols

Protocol for Surface Reaction Energy Calculations

This protocol details the methodology for computing adsorption energies and reaction energetics on catalyst surfaces, based on approaches used in CO2 electroreduction studies [13] [14].

Step 1: Surface Model Construction

- Select the appropriate crystal facet (e.g., Cu(211) for stepped surfaces, Pt(100) for terraces)

- Create a slab model with sufficient thickness (typically 3-5 atomic layers)

- Implement a vacuum layer of at least 15 Ã… to separate periodic images

- For surface reactions, use a p(2×2) or p(3×3) supercell to minimize adsorbate interactions

Step 2: DFT Calculation Parameters

- Employ the GGA-PBE functional for surface reactions (or HSE06 for bandgap-critical systems)

- Use a plane-wave basis set with kinetic energy cutoff of 400-500 eV

- Implement PAW pseudopotentials to describe core-electron interactions

- Set force convergence criterion to < 0.01 eV/Ã… for ionic relaxation

- Use a k-point mesh of (3×3×1) for surface Brillouin zone sampling

Step 3: Energy Computation

- Calculate the total energy of the clean relaxed surface (Esurface)

- Calculate the total energy of the isolated molecule in the gas phase (Emolecule)

- Calculate the total energy of the adsorbed system (Eadsorbate+surface)

- Compute adsorption energy: Eads = Eadsorbate+surface - Esurface - Emolecule

Step 4: Transition State Location

- Employ the Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) method with 5-7 intermediate images

- Use the Dimer method for refined saddle point optimization

- Verify the transition state by vibrational frequency analysis (exactly one imaginary frequency)

Protocol for Electronic Structure Analysis

This protocol describes the methodology for calculating and interpreting electronic properties relevant to catalysis [12] [16].

Step 1: Band Structure Calculation

- Perform initial geometry optimization with high accuracy criteria

- Identify high-symmetry points in the Brillouin zone (Γ, K, M, X, L)

- Run a self-consistent field (SCF) calculation with dense k-point mesh

- Calculate band structure along predetermined high-symmetry paths

- Analyze direct vs. indirect bandgaps and band degeneracies

Step 2: Density of States Analysis

- Compute total DOS with enhanced k-point sampling (>1000 points in full Brillouin zone)

- Perform projected DOS (PDOS) onto atomic orbitals of interest

- Decompose contributions by angular momentum (s, p, d, f orbitals)

- Integrate DOS near Fermi level (-2 eV to +2 eV) to estimate carrier concentration

- Identify orbital hybridization through PDOS peak alignment

Step 3: Work Function Calculation

- Model the appropriate surface slab with sufficient vacuum

- Compute electrostatic potential throughout the simulation cell

- Determine the vacuum potential level far from the surface

- Calculate WF as difference between vacuum level and Fermi energy

- Repeat for different crystal facets to assess anisotropy

The Catalyst Design Workflow

The integration of DFT calculations into catalyst design follows a systematic workflow that connects computational predictions with experimental validation. This pipeline has proven particularly effective in electrocatalysis, where DFT-derived descriptors guide the discovery of advanced materials.

This workflow exemplifies the modern paradigm of computational catalyst design. For CO electroreduction to acetate, researchers identified CH* binding energy as the key descriptor through DFT-based microkinetic modeling [13]. Active learning optimization predicted Cu/Pd (2:1) and Cu/Ag (3:1) alloys as promising candidates, which were subsequently synthesized and tested, achieving Faradaic efficiencies of 50% and 47% respectively—more than double that of pure Cu (21%) [13]. Similarly, for CO2-to-CH4 conversion, a five-step DFT screening strategy identified nine single-atom catalysts superior to conventional Cu(211), with Pd@C5N exhibiting a remarkably low limiting potential of 0.42 V [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful implementation of DFT calculations requires both software tools and computational approaches tailored to catalytic applications.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Catalytic DFT

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Catalytic Application | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT Software Packages | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, CASTEP, GPAW | General catalyst screening | Electronic structure calculation with periodic boundary conditions |

| Electronic Structure Analysis | VESTA, VASPKIT, BAND | DOS, band structure, charge density analysis | Visualization and processing of DFT outputs |

| Transition State Location | CI-NEB, Dimer Method, ART | Reaction pathway mapping | Location of saddle points and minimum energy paths |

| Microkinetic Modeling | CATKINAS, KMOS, ZACROS | Reaction rate prediction | Connecting electronic structure to catalytic rates |

| Machine Learning Integration | AMP, SchNet, PhysNet | Accelerated catalyst screening | Learning structure-property relationships from DFT data |

| KRAS G13D peptide, 25 mer | KRAS G13D peptide, 25 mer, MF:C118H201N29O36S, MW:2634.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 4,5-Dioxodehydroasimilobine | 4,5-Dioxodehydroasimilobine, MF:C17H11NO4, MW:293.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The integration of artificial intelligence with DFT represents a transformative advancement in computational catalysis. AI algorithms can predict electronic responses under physical constraints, accelerate parameter screening, and enhance DFT interpretation reliability [16]. For instance, large language models have been combined with grand-canonical DFT to accelerate the discovery of efficient electrocatalysts, successfully guiding the synthesis of asymmetric FeN4 sites for oxygen reduction reaction with superior stability (>90% activity retention after 30,000 cycles) [17]. Similarly, machine learning models (XGBoost, Random Forest) trained on DFT-derived features have identified key catalyst parameters—d-electron count, first ionization energy, d-band center, and atomic radius—as dominant factors governing CO2 reduction performance [14].

DFT calculations provide an indispensable toolkit for mapping the catalytic landscape through precise computation of energies, structures, and electronic properties. The protocols and methodologies outlined herein enable researchers to quantitatively connect atomic-scale phenomena with macroscopic catalytic performance. As DFT continues to evolve through integration with machine learning approaches and advanced computational frameworks, its predictive power in catalyst design will further accelerate the discovery of next-generation materials for sustainable energy and chemical processes. The successful application of these computational strategies, demonstrated through the guided discovery of high-performance catalysts for CO and CO2 electroreduction, underscores the transformative potential of DFT-driven catalyst design in addressing pressing challenges in renewable energy and sustainable chemistry.

In the realm of density functional theory (DFT) calculations for catalyst design, the selection of an appropriate basis set is not merely a technical detail but a fundamental strategic decision that directly determines the accuracy, reliability, and computational feasibility of simulations. Basis sets—the mathematical functions used to represent electronic orbitals—form the very foundation upon which quantum chemical calculations are built. For researchers investigating catalytic processes, whether in homogeneous, heterogeneous, or enzymatic systems, the choice between two predominant paradigms—plane-wave (PW) and atomic-centered (localized orbital) basis sets—carries significant implications for predicting adsorption energies, reaction barriers, and electronic properties with the precision required for rational catalyst design.

The critical importance of this selection stems from its direct connection to two pivotal aspects of computational modeling: (1) the faithfulness of physical representation of the electronic structure in diverse chemical environments, and (2) the practical computational cost associated with modeling realistic catalyst systems. A poorly chosen basis set can introduce artifacts such as basis set superposition error (BSSE) or fail to adequately describe key electronic effects, leading to qualitatively incorrect predictions regarding catalytic activity or selectivity [18] [19]. Conversely, an optimally chosen basis set provides the optimal compromise between accuracy and computational efficiency, enabling high-throughput screening of catalyst candidates or detailed mechanistic studies with predictive reliability.

This application note provides a comprehensive framework for selecting between plane-wave and atomic-centered basis sets within the specific context of DFT calculations for catalyst design. By synthesizing current theoretical understanding with practical benchmarking studies, we establish structured protocols to guide researchers in making informed methodological choices tailored to their specific catalytic systems and research objectives.

Theoretical Foundations: Plane-Wave vs. Atomic-Centered Basis Sets

Fundamental Definitions and Mathematical Representations

Plane-wave (PW) basis sets expand the electronic wavefunctions as a superposition of periodic functions defined throughout the simulation cell:

[ \psii(\mathbf{r}) = \sum{\mathbf{G}} c_{\mathbf{G}} e^{i\mathbf{G} \cdot \mathbf{r}} ]

where (\mathbf{G}) represents the reciprocal lattice vectors, and the summation is truncated at a specific kinetic energy cutoff ((E_{\text{cut}} = \frac{\hbar^2 |\mathbf{G}|^2}{2m})) that determines the basis set quality [20] [19]. This uniform, spatially delocalized representation naturally embodies translational symmetry, making PWs the default choice for periodic systems.

Atomic-centered basis sets, also known as localized orbital basis sets, employ functions centered on atomic nuclei, typically as a linear combination of Gaussian-type orbitals (GTOs):

[ \phi\mu(\mathbf{r}) = \sump d{p\mu} Np r^{l} e^{-\alphap r^2} Y{lm}(\theta,\phi) ]

where (Y{lm}) are spherical harmonics, and the contraction coefficients (d{p\mu}) and exponents (\alpha_p) are optimized for specific elements [18] [21]. This atom-centered approach provides a chemically intuitive representation that naturally concentrates computational resources near atomic cores where electron density varies most rapidly.

Comparative Analysis of Fundamental Properties

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Plane-Wave and Atomic-Centered Basis Sets

| Property | Plane-Wave Basis Sets | Atomic-Centered Basis Sets |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Representation | Delocalized, uniform in real space | Localized on atomic centers |

| Systematic Improvability | Single parameter (cutoff energy) | Multiple parameters (cardinal number, diffuse functions) |

| Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE) | Virtually nonexistent [19] | Can be significant, requires counterpoise correction [18] [19] |

| Computational Scaling | Favorable for dense k-point sampling | More favorable for hybrid functionals [20] |

| Default Applicability | Periodic systems (bulk crystals, surfaces) | Molecular systems, clusters [1] [18] |

| Core Electron Treatment | Typically uses pseudopotentials | Can treat all-electron or use effective core potentials |

Basis Set Selection Protocol for Catalytic Systems

The selection between plane-wave and atomic-centered basis sets hinges primarily on the dimensionality and electronic structure of the catalytic system under investigation. The following decision protocol provides a systematic approach for researchers.

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for basis set selection in catalytic systems. BSSE refers to basis set superposition error.

Application-Specific Selection Guidelines

Heterogeneous Catalysis (Periodic Systems)

For metallic surfaces and solid catalysts, plane-wave basis sets typically offer significant advantages. Benchmarking studies on Fe(110) surfaces demonstrate that PW basis sets achieve faster convergence for small slab models while maintaining superior stability for larger supercells [20]. The absence of BSSE is particularly advantageous when studying molecular adsorption on catalytic surfaces, where weak interactions (e.g., physisorption) must be accurately characterized [19].

Protocol for Metallic Surface Calculations:

- Initial Setup: Construct slab model with appropriate vacuum spacing (≥15 Å)

- Plane-Wave Cutoff: Converge total energy with respect to cutoff energy (typically 400-600 eV for transition metals)

- k-point Sampling: Implement Monkhorst-Pack grid with density sufficient to converge adsorption energies (<0.01 eV)

- Validation: Compare surface energies with localized basis set (e.g., pob-TZVP) when feasible

Homogeneous and Molecular Catalysis

For discrete molecular systems, organometallic complexes, and enzyme active sites, atomic-centered basis sets provide superior computational efficiency and more natural representation of local electronic structure. The ability to employ hybrid functionals without prohibitive computational cost makes them particularly valuable for studying reaction mechanisms where accurate electronic exchange is critical [18].

Protocol for Molecular Catalyst Systems:

- Basis Set Selection: def2-TZVP or def2-SVPD for exploratory scans; def2-QZVPP for final single-point energies

- Dispersion Correction: Include D3(BJ) empirical dispersion corrections [18]

- BSSE Management: Apply counterpoise correction for weakly interacting complexes [19]

- Solvation Effects: Incorporate implicit solvation models (e.g., SMD, COSMO) for solution-phase catalysis

Hybrid and Multiscale Systems

Emerging catalyst architectures such as single-atom catalysts (SACs), metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and supported molecular catalysts present unique challenges that may benefit from mixed approaches. The Universal Model for Atoms (UMA) architecture recently introduced by Meta's FAIR team represents a promising direction, employing a Mixture of Linear Experts (MoLE) approach to unify diverse chemical datasets across multiple domains [22].

Performance Benchmarking and Convergence Protocols

Quantitative Comparison for Representative Systems

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks for Plane-Wave vs. Atomic-Centered Basis Sets

| System Type | Property | Plane-Wave Results | Atomic-Centered Results | Experimental/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe(110) Surface [20] | Work Function | 4.70 eV | 4.92 eV | ~4.8 eV |

| Fe(110) Surface [20] | Surface Energy | 2.12 J/m² | 2.35 J/m² | 2.0-2.5 J/m² |

| Molecular Crystal [23] | THz Spectrum (RMSD) | - | PBE/pob-TZVP: 0.81 cmâ»Â¹ (H-bond) | Experimental reference |

| S22 Noncovalent Dimers [19] | MP2 Interaction Energy (MAE) | CBS Reference | aug-cc-pV5Z: 0.05 kcal/mol | - |

| Biomolecules [22] | Energy Accuracy (WTMAD-2) | - | OMol25-trained NNPs: near-DFT | High-level DFT reference |

Practical Implementation Protocols

Plane-Wave Convergence Protocol for Surface Calculations

Software: VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, CASTEP System: Transition metal surface (e.g., Pt(111), Fe(110))

Pseudopotential Selection:

- Use PAW (Projector Augmented Wave) pseudopotentials

- Verify consistent treatment of valence electrons across compared elements

Energy Cutoff Convergence:

- Perform single-point calculations with increasing ENCUT (300-700 eV)

- Select cutoff where total energy change < 1 meV/atom

- Typical values: 400-520 eV for 3d metals, 250-400 eV for main group elements

k-point Grid Convergence:

- Start with Γ-point only for structure relaxation

- Increase k-point density until adsorption energies converge to <0.01 eV

- Typical grids: 3×3×1 to 11×11×1 for surface calculations

Vacuum Thickness Verification:

- Ensure minimal interaction between periodic images (≥15 Å)

- Confirm dipole corrections implemented for asymmetric slabs

Atomic-Centered Basis Set Protocol for Molecular Catalysts

Software: Gaussian, ORCA, CP2K/Quickstep System: Organometallic catalyst (e.g., transition metal complex)

Basis Set Hierarchy:

- Geometry optimization: def2-SVPD or def2-TZVP

- Single-point energy: def2-QZVPP

- Spectral properties: aug-cc-pVTZ (main group), def2-TZVP (metals)

BSSE Management:

- Apply counterpoise correction for intermolecular interactions

- Use Boys-Bernardi counterpoise correction for supramolecular systems

Integration Grid Selection:

- Use "UltraFine" grid in Gaussian or equivalent in other packages

- Verify integration accuracy for metal centers with large grids (99,590 points) [22]

The Computational Catalyst Design Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Basis Set Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| VASP [20] | Software Package | Plane-wave DFT with PAW pseudopotentials | Periodic surfaces, solid catalysts, electrochemical interfaces |

| Gaussian [21] | Software Package | Molecular DFT with atomic-centered basis sets | Molecular catalysts, reaction mechanisms, spectroscopic properties |

| CRYSTAL [20] | Software Package | Periodic DFT with localized basis sets | Mixed-dimensionality systems, molecular crystals |

| def2 Basis Sets [18] | Atomic-Centered Basis Set | Balanced accuracy/efficiency for elements 1-86 | Molecular catalyst screening, mechanistic studies |

| cc-pVXZ Families [19] | Atomic-Centered Basis Set | Systematic correlation-consistent convergence | High-accuracy thermochemistry, noncovalent interactions |

| Pseudopotential Libraries | Pseudopotential Database | Consistent core electron treatment | Plane-wave calculations across periodic table |

| Basis Set Exchange [21] | Basis Set Repository | Access to standardized basis sets | Reproducible atomic-centered calculations |

| OMol25 Dataset [22] | Training Data | Neural network potential development | Large-scale catalyst screening with DFT accuracy |

| 2,4-Dichloro-6-phenyl-1,3,5-triazine-d5 | 2,4-Dichloro-6-phenyl-1,3,5-triazine-d5, MF:C9H5Cl2N3, MW:231.09 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| iso-Hexahydrocannabinol | iso-Hexahydrocannabinol | High-purity iso-Hexahydrocannabinol for research. A hydrogenated cannabinoid for pharmacological and metabolic studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

Emerging Methods and Future Directions

The historical dichotomy between plane-wave and atomic-centered approaches is increasingly being bridged by methodological advances. The eSEN (equivariant Scalar-Efficient Network) architecture and UMA (Universal Models for Atoms) framework demonstrate how neural network potentials trained on massive computational datasets (e.g., OMol25 with 100+ million calculations) can achieve DFT-level accuracy while dramatically reducing computational cost [22]. These approaches effectively learn optimal representations that capture the strengths of both basis set paradigms.

For high-throughput catalyst screening, composite methods like r2SCAN-3c and B97M-V/def2-SVPD with DFT-C corrections offer improved accuracy over outdated defaults like B3LYP/6-31G*, while maintaining computational efficiency [18]. The development of variational even-tempered basis sets provides promising avenues for system-specific optimization beyond standardized basis sets [24].

As catalytic systems grow increasingly complex—spanning hierarchical materials, interfacial environments, and dynamic non-equilibrium states—the strategic selection and potential combination of basis set approaches will remain essential for predictive computational catalyst design.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has emerged as a foundational computational tool in the design and optimization of sustainable technologies. By enabling researchers to probe material properties and reaction mechanisms at the atomic scale, DFT provides critical insights that guide the development of next-generation energy storage systems, energy conversion catalysts, and novel materials. This article details specific protocols and applications where DFT calculations are directly impacting the creation of sustainable technologies, from batteries with enhanced safety and performance to catalysts that drive critical energy conversion reactions. The integration of DFT with emerging machine learning (ML) methods is further accelerating this design process, creating a powerful toolkit for predictive materials science.

Application Note: Multi-scale Thermal Safety Framework for Lithium-Ion Batteries

Background and Objective

The safety of Lithium-Ion Batteries (LIBs) is paramount, especially under extreme operational conditions that can lead to hazardous thermal runaway. Traditional models often rely on empirical fitting, which can limit their predictive accuracy and mechanistic insight. A multi-scale framework that integrates DFT with empirical electrochemical modeling has been developed to fundamentally evaluate and predict the thermal behavior of electrodes, thereby enhancing both battery performance and safety [25].

Key Workflow and Findings

This framework employs DFT simulations to refine critical electrode properties—such as dielectric constants, bond strengths, and structural stability—which are subsequently transformed into temperature-dependent parameters for thermal runaway analysis. These atomistic descriptors are integrated into a lumped-parameter electrochemical–thermal model to account for coupled phenomena, including heat generation, ionic transport, and decomposition pathways [25]. A diagnostic protocol using the Finite Volume Method is then applied to evaluate electrode stability under thermal stress.

Table 1: DFT-Derived Electrode Properties for Thermal Modeling

| Property Category | Specific Properties | Role in Thermal Model |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure | Redox Potentials, Energy States, Dielectric Constants | Input for macroscopic heat generation terms |

| Bonding & Stability | Bond Strengths, Structural Stability | Determines decomposition pathways and thermal stability |

| Transport | Diffusion Barriers, Thermal Conductivities | Models ionic transport and heat dissipation |

The innovation of this approach lies in creating a physics-based link between atomic-scale insights and system-level cooling performance. This allows for a mechanistic prediction of instability with greater accuracy than traditionally possible. The methodology is not limited to LIBs and can be extended to emerging chemistries like sodium-ion and solid-state batteries [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Battery Thermal Safety Screening

| Research Reagent (Software/Code) | Function |

|---|---|

| DFT Simulation Package (e.g., CASTEP, VASP) | Calculates fundamental electronic structure and material properties. |

| Finite Volume Method Solver | Solves continuum-scale equations for heat and mass transfer. |

| Lumped-Parameter Electrochemical–Thermal Model | Integrates atomistic and continuum descriptions to predict system behavior. |

Application Note: Designing High-Performance Triatomic Catalysts for Energy Conversion

Background and Objective

Triatomic Catalysts (TACs), comprising three metal atoms as active sites, represent a frontier in catalysis due to their ultra-high atomic utilization and superior activity and selectivity in multi-electron reactions. DFT calculations are instrumental in screening and designing these complex materials, particularly by elucidating the critical role of the support material in modulating catalytic performance [26].

Key Workflow and Findings

DFT guides the rational design of TACs by enabling the computational screening of various metal atom combinations and their coordination environments on different supports. Key performance metrics calculated include the adsorption free energy of reaction intermediates, electronic structure (e.g., d-band center), and metal-support interaction strength [26]. This helps in optimizing TACs for crucial energy conversion reactions like the Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR), CO~2~ Reduction Reaction (CO~2~RR), and N~2~ Reduction Reaction (NRR).

Carbon-based materials like graphene and carbon nanotubes are prominent supports, prized for their high conductivity and tunability. DFT studies have shown that introducing dopant atoms (e.g., N, B, S, P) or defects into the carbon lattice can significantly alter the electronic structure of the TAC, optimizing the binding of intermediates and enhancing catalytic performance [26]. The stability of TACs, a major challenge, is also assessed through DFT calculations of binding energies and diffusion barriers, which predict resistance to atomic aggregation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Components for Triatomic Catalyst Development

| Component / Reagent | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Carbon-Based Supports (Graphene, CNTs) | Provide high surface area, conductivity, and facilitate strong metal-support interactions. |

| Heteroatom Dopants (N, B, S, P) | Modify the electronic structure of the support and metal center to optimize intermediate adsorption. |

| Defect Engineering (e.g., vacancies) | Create anchoring sites to stabilize metal atoms and prevent agglomeration. |

Application Note: High-Throughput Screening of Azobenzene Derivatives for Solar Energy Storage

Background and Objective

Molecular Solar Thermal (MOST) fuels, particularly those based on azobenzene (AB) derivatives, can store solar energy in their molecular bonds via photoinduced E/Z isomerization. A key challenge is the high-throughput computational screening of AB derivatives to identify candidates with optimal energy storage density and thermal stability of the metastable Z-isomer. Standard DFT methods often fail to accurately describe the transition state region of the thermal isomerization pathway due to its multi-configurational character [27].

Key Workflow and Findings

A hybrid computational protocol was developed to achieve quasi-CASPT2 (a highly accurate multi-reference method) accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost. This protocol involves using DFT for initial structural scans, which is computationally efficient, and then applying high-level CASPT2/CASSCF calculations on key points along the reaction coordinate to correct the energies, particularly near the transition state [27].

Table 4: Key Properties for Azobenzene MOST Screening from DFT/Multi-reference Calculations

| Property | Description | Impact on MOST Performance |

|---|---|---|

| E/Z Energy Gap (ΔE) | Energy difference between E and Z isomers. | Determines the maximum energy stored per molecule. |

| Z → E Isomerization Barrier (E~a~) | Activation energy for the thermal back-reaction. | Governes the thermal half-life (stability) of the "charged" Z isomer. |

| Reaction Path (Inversion vs. Torsion) | The mechanism of thermal isomerization. | Affects the kinetics and can be tuned by chemical substitution. |

This combined approach successfully identified that "pull-pull" substitution (e.g., with nitro groups) in AB derivatives is a promising strategy for MOST applications [27]. The protocol enables accurate estimation of the energy barrier, which directly dictates the thermal half-life of the energy-storing Z-isomer, a critical parameter for practical applications.

Detailed Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol: DFT Investigation of Doped Chevrel Phase Cathode Materials

Application: Screening novel cathode materials (e.g., MgMo~6~S~8-y~Se~y~) for Mg-ion batteries. Objective: To predict structural, electronic, elastic, and electrochemical properties to assess viability before synthesis [28].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Initial Structure Acquisition:

- Obtain the crystal structure of the base compound (e.g., MgMo~6~S~8~) from experimental databases (e.g., ICSD). The Chevrel phase has a triclinic structure with space group \(P\overline{1}\) [28].

Model Construction and Doping:

- Build the doped model (e.g., MgMo~6~S~8-y~Se~y~) by systematically substituting S atoms with Se atoms in the crystal lattice. For a comprehensive study, create supercells to model different doping concentrations (y = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4) [28].

Computational Setup (Using CASTEP or similar plane-wave code):

- Functional: Employ the Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional for exchange-correlation.

- Pseudopotentials: Use ultrasoft Vanderbilt-type pseudopotentials.

- Plane-wave cutoff energy: Set to 350 eV.

- k-point mesh: Use a 4×4×4 Monkhorst-Pack grid.

- Geometry Optimization: Use the BFGS algorithm with convergence criteria of 5×10–6 eV/atom for energy, 0.01 eV/Å for maximum force, and 0.02 GPa for maximum stress [28].

Property Calculation:

- Formation Enthalpy (ΔH~f~): Calculate using the equation provided in [28] to confirm thermodynamic stability. A negative value indicates a stable phase.

- Electronic Properties: Compute the electronic band structure and Density of States (DOS) to determine if the material is metallic or semiconducting and to identify orbital hybridizations (e.g., between Mo-4d and S-3p/Se-4p states).

- Elastic Constants: Calculate the 21 independent elastic constants (C~ij~) using the stress-strain method. Verify mechanical stability using Born-Huang criteria. Derive polycrystalline elastic moduli (Bulk, Shear, Young's) using the Voigt-Reuss-Hill approximation [28].

- Redox Potential: Estimate the average voltage for Mg insertion from the total energy difference between the charged and discharged states.

Protocol: Combined DFT/Multi-reference Protocol for Azobenzene Characterization

Application: Accurate characterization of azobenzene derivatives for Molecular Solar Thermal (MOST) energy storage. Objective: To obtain accurate potential energy profiles for the thermal Z → E isomerization, determining the energy storage density (ΔE) and thermal half-life (via barrier E~a~) [27].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Initial Conformational Search:

- Use molecular mechanics or a cheap DFT method to generate low-energy starting geometries for both the E and Z isomers of the AB derivative.

DFT Pre-optimization and Scans:

- Functional: Use a GGA functional like BP86.

- Basis Set: Use a polarized double-zeta basis set like def2-SVP.

- Procedure: a. Fully optimize the E and Z minimum structures. b. Perform a relaxed surface scan to explore the isomerization pathway. Since pure DFT fails to locate the torsional transition state, perform constrained optimizations. c. For the torsion path, fix the central N=N-C angle (e.g., from 0° to 180° in steps) and optimize all other coordinates. d. For the inversion path, fix one of the C-N=N angles (e.g., from 110° to 180°) and optimize all other coordinates [27].

High-Level Single Point Energy Corrections:

- Method: Use a multi-configurational method: Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field (CASSCF) followed by second-order perturbation theory (CASPT2).

- Active Space: A typical choice is CASSCF(10,8) - 10 electrons in 8 orbitals.

- Basis Set: Use a high-quality basis set like ANO-R1.

- Procedure: Take the key structures from the DFT scans (minima, near-TS regions) and perform single-point energy calculations at the CASPT2 level on these DFT-optimized geometries (a protocol termed CASPT2//DFT) [27].

Data Analysis:

- Plot the CASPT2-corrected potential energy profiles along the torsion and inversion coordinates.

- Identify the lowest-energy transition state and its character (torsion-dominated or inversion-dominated).

- Report the adiabatic E/Z energy gap (ΔE, energy stored) and the Z → E activation barrier (E~a~, related to storage lifetime).

Protocol: AI-Enhanced Catalyst Design with CatDRX Framework

Application: Generative design of novel catalyst molecules conditioned on specific reaction environments. Objective: To move beyond screening and actively generate novel, high-performance catalyst structures for a given reaction [29].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Data Curation and Pre-training:

- Collect a large and diverse dataset of catalytic reactions, including reactants, products, reagents, catalysts, and outcomes (e.g., yield). Databases like the Open Reaction Database (ORD) are suitable.

- Pre-train a Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE) model, such as CatDRX, on this broad dataset. This model learns a latent representation of catalysts that is conditioned on the other components of the reaction [29].

Model Fine-Tuning:

- For a specific catalytic reaction of interest (e.g., a certain cross-coupling), fine-tune the pre-trained model on a smaller, specialized dataset. This adapts the model's knowledge to the specific domain.

Catalyst Generation and Prediction:

- Input: Define the reaction conditions (reactants, desired products, reagents).

- Generation: The conditioned decoder samples from the latent space to generate novel catalyst structures in the form of SMILES strings or molecular graphs.

- Prediction: The integrated predictor module estimates the catalytic performance (e.g., yield) for the generated candidates [29].

Validation and Optimization:

- Filtering: Use chemical knowledge (e.g., synthetic accessibility, functional group compatibility) to filter the generated candidates.

- Optimization: Use optimization techniques (e.g., Bayesian optimization) on the latent space to steer generation toward candidates with higher predicted performance.

- Computational Validation: Perform DFT calculations on top-generated candidates to validate stability and predicted mechanism before experimental testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 5: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for DFT-Guided Sustainable Technology Research

| Category / Name | Function / Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Plane-Wave DFT Codes (CASTEP, VASP) | Perform periodic boundary condition calculations for crystals and surfaces. | Calculating formation enthalpy and electronic structure of Chevrel phase cathode materials [28]. |

| Gaussian 09/16 | Performs quantum chemical calculations on molecules using localized basis sets. | Investigating the electronic properties of C~12~ nanorings for Na-ion batteries [30]. |

| ωB97XD Functional | A range-separated DFT functional including empirical dispersion correction. | Used for thermodynamic and electronic property analysis of molecular systems like carbon nanorings [30]. |