From Alchemy to Oncology: The Evolutionary Journey of Catalysts in Science and Medicine

This article traces the transformative journey of catalyst development from its origins in ancient alchemy to its pivotal role in modern drug development and clean energy.

From Alchemy to Oncology: The Evolutionary Journey of Catalysts in Science and Medicine

Abstract

This article traces the transformative journey of catalyst development from its origins in ancient alchemy to its pivotal role in modern drug development and clean energy. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of catalysis, examines methodological breakthroughs from industrial to biomedical applications, analyzes troubleshooting and optimization strategies for modern catalytic systems, and validates performance through advanced characterization techniques. The synthesis provides a comprehensive historical and technical framework to inform future innovations in catalytic processes for biomedical research and therapeutic development.

From Ancient Transmutations to Scientific Foundations: The Origins of Catalysis

Alchemy, often misunderstood as mere mysticism, was in fact a complex and systematic protoscientific tradition that laid the groundwork for modern chemistry and catalyst development [1]. Practised for over a millennium across China, India, the Islamic world, and Europe, alchemy represents humanity's early organized attempt to understand and manipulate matter through experimental processes [2]. While its spiritual and philosophical dimensions sought personal transformation and enlightenment, its practical laboratory work established fundamental principles of material transformation that directly prefigure contemporary catalytic science [3] [4]. This paper examines medieval alchemy not as a historical curiosity but as the intellectual and methodological precursor to modern catalyst research, tracing a direct lineage from the alchemist's laboratory to today's industrial catalytic processes.

The alchemical tradition developed a sophisticated conceptual framework for understanding chemical transformations, establishing laboratory techniques that remain central to chemical research, and creating an initial classification system for substances and their reactive properties [5] [2]. Within this tradition, we find the earliest systematic investigations into substances that facilitate transformations without being consumed—the fundamental principle of catalysis. By examining alchemical practices through the lens of modern catalyst science, we can appreciate their substantive contributions to the development of this critical field.

Philosophical and Theoretical Foundations

Alchemical philosophy was rooted in the concept of transformation at both material and spiritual levels. The famous alchemical dictum "as above, so below," from the Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus, expressed the belief that processes in the microcosm reflected those in the macrocosm [1] [2]. This principle guided alchemists in their belief that base metals could be transformed into noble ones, just as the human soul could achieve perfection [6]. The theoretical framework rested on several key concepts that, while different from modern scientific understanding, provided a systematic approach to investigating material transformations.

Central to alchemical theory was the concept of the Philosopher's Stone, a substance believed to possess the power to transmute base metals into gold and, in some traditions, to produce the Elixir of Life for immortality [1] [2]. This pursuit, while never achieving its mythical goal, drove centuries of experimental work that developed practical laboratory techniques and discovered numerous substances with genuine catalytic properties. The conceptualization of a substance that could facilitate profound transformations without being consumed itself represents a prescient understanding of what would later be recognized as catalytic action [3].

Alchemical practice also incorporated Aristotelian philosophy, particularly the theory that all matter was composed of four elements—earth, air, fire, and water—each possessing qualities of hot, cold, wet, or dry [4]. Transmutation was theorized to occur through the rearrangement of these fundamental qualities. This theoretical framework, while ultimately incorrect, provided alchemists with a systematic approach to experimenting with material transformations that established patterns of investigation that would later evolve into proper scientific methodology.

Key Alchemical Substances and Processes

Medieval alchemists developed a sophisticated inventory of substances and laboratory processes that advanced material science and established techniques fundamental to chemical research. Their work identified and characterized numerous compounds that would later be recognized as having genuine catalytic properties, while their experimental methods established procedural approaches that remain relevant to contemporary catalyst research.

Alchemical Substances with Catalytic Significance

Table 1: Key Alchemical Substances and Their Modern Correlates

| Alchemical Name | Modern Identification | Alchemical Function | Catalytic Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sal ammoniac | Ammonium chloride (NH₄Cl) [7] | Flux in metalworking [7] | Acidic catalyst; metal salt precursor |

| Quicksilver | Mercury (Hg) [7] | Principal material for transmutation [7] | Amalgamation; reduction reactions |

| Butter of Antimony | Antimony trichloride (SbCl₃) [7] | Transmutation agent [7] | Lewis acid catalyst |

| Oil of Vitriol | Sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) [7] | Solvent; reactive medium [7] | Acid catalyst; dehydrating agent |

| Luna Cornea | Silver chloride (AgCl) [7] | Material transformation [7] | Light-sensitive catalyst precursor |

| Nix Alba | Zinc oxide (ZnO) [7] | Pigment; medicinal [7] | Heterogeneous catalyst; semiconductor |

These substances were employed in increasingly sophisticated laboratory procedures that allowed alchemists to pursue their transformative goals while simultaneously building practical knowledge about chemical processes. The preparation and purification of these materials represented significant technical achievements that expanded the available toolkit for experimental investigation.

Fundamental Laboratory Processes

Alchemists developed and refined numerous laboratory techniques that would become standard procedures in chemistry laboratories. These processes were not merely mechanical operations but were viewed as stages in the transformative work that had both physical and spiritual dimensions:

Calcination: The heating of substances to high temperatures in air or oxygen to induce thermal decomposition, remove volatile components, or induce phase transitions [6]. This process was used to produce metal oxides from metals or carbonates.

Distillation: The purification or separation of mixture components through evaporation and condensation, greatly advanced by Arabic alchemists like Jabir ibn Hayyan [5] [2]. This technique enabled the production of concentrated acids and other reagents.

Sublimation: The transition of a substance directly from solid to gas phase, used particularly with compounds like ammonium chloride and arsenic trioxide [7].

Solution and Precipitation: The dissolution of materials in solvents followed by selective precipitation, used for purification and material separation [7].

Fermentation: Biological transformation processes studied not only for alcohol production but as a model for other transformative processes [5].

These operations formed a comprehensive experimental methodology that allowed alchemists to manipulate matter systematically, observing patterns of reactivity and transformation that would later inform the development of modern chemistry.

Experimental Protocols in Alchemy

Medieval alchemical research followed systematic experimental approaches that, while often shrouded in symbolic language, represented methodical investigations into material transformations. The following reconstructed protocols illustrate the sophistication of alchemical experimental design and its relevance to catalyst development.

Preparation of Aqua Fortis (Nitric Acid)

Objective: To produce a strong mineral acid capable of dissolving nearly all metals except gold, used in assaying and material processing [7].

Materials Required:

- Saltpetre (potassium nitrate, KNO₃) [7]

- Oil of Vitriol (sulfuric acid, H₂SO₄) [7]

- Aludel or glass retort with receiver vessel

- Heat source (furnace or sand bath)

Experimental Procedure:

- Combine two parts saltpetre with one part oil of vitriol in the retort [7].

- Assemble the distillation apparatus with tight seals to prevent gas escape.

- Apply gradual heat, increasing temperature until red fumes appear.

- Collect the distilled liquid in the receiver vessel.

- Observe the production of a fuming, highly corrosive liquid that dissolves copper and silver.

Significance: This process represented one of the earliest productions of a pure mineral acid, creating a powerful reactive medium that enabled numerous other chemical investigations and material processes. The ability to produce such reactive species was fundamental to advancing experimental chemistry.

The Cementation Process for Metal Purification

Objective: To separate gold from lesser metals or to produce surface modifications on metals through solid-state diffusion [7].

Materials Required:

- Metal sheets or objects to be treated

- Powdered cementation compound (typically salts, minerals, or other reactive solids)

- Layered ceramic or metal container

- Controlled-temperature furnace

Experimental Procedure:

- Alternate layers of metal and powdered cementation material in the container.

- Seal the container to limit gas exchange while allowing pressure regulation.

- Heat the assembly in a furnace for extended periods (typically days to weeks).

- Maintain consistent temperature below the melting point of the metals.

- After cooling, remove the metal objects and observe surface modifications or purification.

Significance: Cementation represented an early form of heterogeneous catalysis and materials processing, demonstrating how solid-phase reactions could effect material transformations—a principle fundamental to modern heterogeneous catalyst systems.

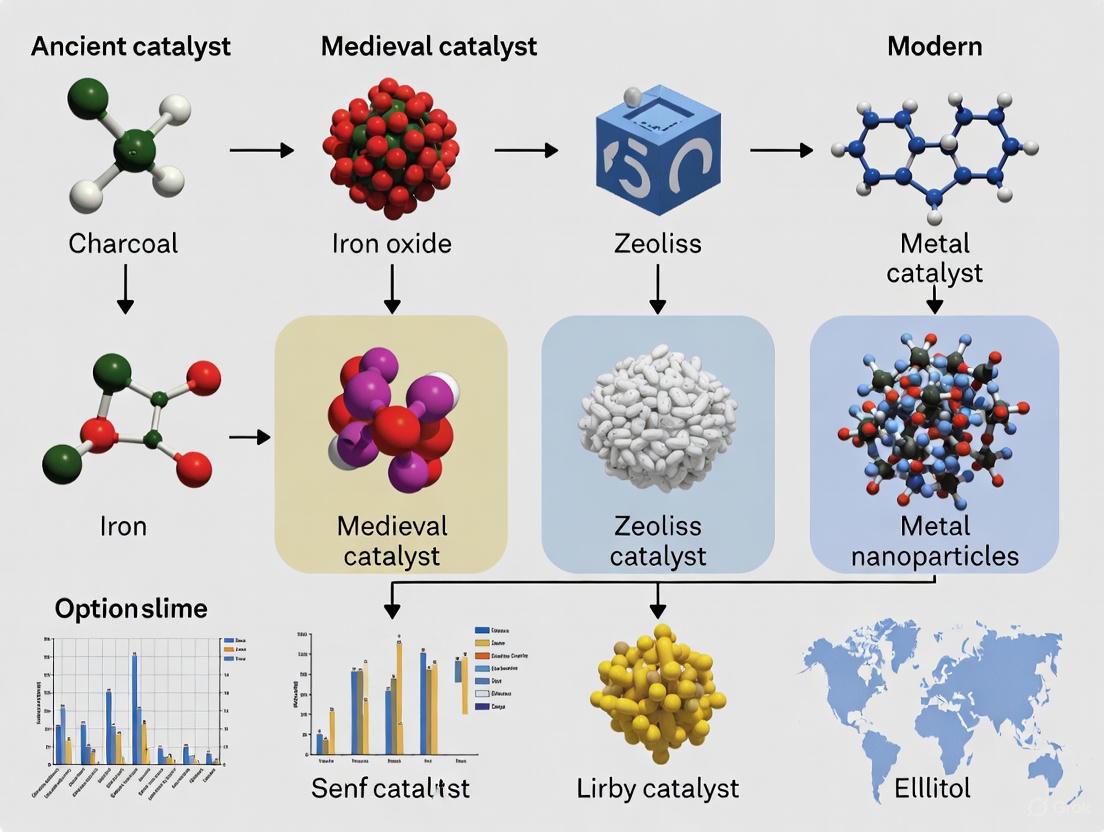

Figure 1: The Alchemical Experimental Methodology showing the transformation process workflow from input materials through various operations to output products, demonstrating the systematic approach to material transformations.

The Alchemical Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

The alchemical laboratory contained a sophisticated array of substances with specific functions, many of which would later be recognized as catalysts or catalyst precursors. This repertoire represented centuries of accumulated knowledge about material properties and reactivities.

Table 2: Essential Alchemical Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent Name | Composition | Primary Function | Modern Catalytic Analog |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aqua Regia | HCl:HNO₃ mixture (3:1) [7] | Dissolution of noble metals | Precious metal catalyst preparation |

| Mercurius Praecipitatus | Red mercuric oxide (HgO) [7] | Oxidizing agent | Oxidation catalyst precursor |

| Flowers of Antimony | Antimony trioxide (Sb₂O₃) [7] | Opacifier; medicinal | Solid acid catalyst component |

| Sugar of Lead | Lead acetate (Pb(CH₃COO)₂) [7] | Sweetening agent; glaze | Coordination compound; catalyst poison |

| White Arsenic | Arsenious oxide (As₂O₃) [7] | Medicinal; poison | Catalyst inhibitor/poison |

| Liver of Sulfur | Potassium polysulfide mixture [7] | Surface modification | Heterogeneous catalyst pretreatment |

| Sal Alembroth | Chlorides of ammonium and mercury [7] | Universal solvent (claimed) | Dual-component catalyst system |

This toolkit enabled alchemists to conduct a wide range of chemical transformations and material characterizations. The functional understanding of these substances—their selective reactivities, synergistic effects, and transformational capabilities—represented significant progress toward the conceptualization of catalytic action, even if the theoretical framework differed from modern understanding.

Historical Continuity: From Alchemy to Catalysis

The transition from alchemy to modern chemistry and catalysis was not a sharp break but a gradual evolution, with many key figures bridging these traditions. This continuity is evident in both conceptual frameworks and practical methodologies.

Conceptual Inheritance

The fundamental alchemical concept of a substance that could facilitate transformations without being consumed itself finds direct expression in the modern definition of a catalyst. The Philosopher's Stone, while mythologized beyond practical reality, conceptually prefigures the catalyst—a substance that enables transformations while remaining unchanged [3]. This parallel is not merely symbolic; the experimental pursuit of transmutation directly led to the discovery of substances with genuine catalytic properties.

The alchemical emphasis on process and transformation, rather than merely static composition, established a conceptual framework that would later prove essential to understanding catalytic cycles and reaction kinetics. The recognition that materials passed through different stages and states during transformations, a central feature of alchemical theory, anticipated modern understanding of reaction mechanisms and intermediate species in catalytic processes.

Methodological Continuity

The laboratory techniques refined by alchemists—distillation, sublimation, solution/precipitation, and temperature-controlled reactions—became the standard methodologies of chemical research [2] [4]. These processes remain essential in modern catalyst preparation and characterization. The development of specialized glassware, furnaces, and reaction vessels by alchemists created the physical infrastructure that enabled advanced chemical investigations.

The alchemical approach to systematic experimentation, while often incorporating symbolic and qualitative observations, established patterns of investigative methodology that would later be refined into proper scientific protocol. The careful documentation of procedures, materials, and observations—even when interpreted through pre-scientific theoretical frameworks—created a body of empirical knowledge that informed later scientific developments.

Influential Figures Bridging the Traditions

Several key figures demonstrate the direct lineage from alchemical traditions to modern chemical science:

Jabir ibn Hayyan (Geber): This 8th-century Persian alchemist introduced systematic experimentation and laboratory techniques such as distillation, crystallization, and sublimation [2]. His work with mineral acids and methodical approach to experimentation established foundational practices for chemical research.

Paracelsus (1493-1541): The Swiss physician-alchemist revolutionized medicine by introducing chemically-prepared medicines, moving beyond traditional herbal remedies [2] [8]. His concept of using prepared chemicals for therapeutic effect established principles that would inform both pharmacology and catalyst design.

Robert Boyle (1627-1691): Though critical of some alchemical traditions, Boyle's corpuscular theory of matter was influenced by alchemical concepts, particularly through his engagement with the work of Daniel Sennert [4]. His systematic approach to experimentation built upon alchemical methodologies while introducing greater rigor.

Isaac Newton (1642-1727): Newton's extensive alchemical researches, long overlooked, demonstrate the continued engagement with alchemical concepts even as modern science was emerging [2] [4]. His investigations into material transformations informed his broader scientific worldview.

The medieval pursuit of transformation through alchemy established conceptual, methodological, and technical foundations that directly informed the development of modern catalysis. While the mystical dimensions of alchemy have often obscured its substantive contributions, a rigorous examination reveals significant continuity between these traditions. The alchemical emphasis on transformation processes, development of laboratory techniques for material manipulation, and investigation of substances that facilitate change without being consumed all prefigure key aspects of contemporary catalyst science.

Modern industrial catalysis, with over 90% of industrial chemicals now produced using catalytic processes, stands as the direct descendant of these early investigations into material transformations [9] [10]. From the development of catalytic cracking of petroleum by Eugène Houdry in the 1930s to the Ziegler-Natta polymerization catalysts that revolutionized plastics production, the fundamental principle remains the same: substances that facilitate transformations while being regenerated [9]. This principle was presaged in alchemical investigations centuries before the term "catalyst" was formally coined in 1835 [3].

The historical narrative that positions alchemy as merely a pre-scientific superstition fails to acknowledge its substantive contributions to the conceptual and methodological toolkit of chemical research. By recognizing alchemy as a legitimate protoscientific tradition with direct relevance to catalyst development, we gain not only a more accurate historical understanding but also appreciation for the complex, non-linear nature of scientific progress. The alchemical pursuit of transformation, both material and spiritual, established investigative patterns and conceptual frameworks that continue to inform cutting-edge catalyst research today, including emerging fields such as biocatalysis, electrocatalysis, and photocatalytic processes for sustainable energy applications [10].

The dawn of industrial catalysis marked a pivotal transformation in chemical synthesis, enabling efficient large-scale production of essential compounds that shaped modern industry and medicine. Among these foundational processes, the synthesis of ethers stands as a cornerstone development that not only revolutionized industrial chemistry but also established principles that would later permeate therapeutic innovation. This transition from traditional alchemical practices to systematic catalytic processes represents a critical junction in the history of chemistry, where empirical knowledge converged with emerging scientific principles to create reproducible, scalable synthetic methodologies. The evolution of ether production exemplifies this paradigm shift, moving from simple distillation techniques to sophisticated catalytic systems that would eventually inspire entirely new fields of medical research, including contemporary advances in nanocatalytic medicine. By examining the birth and maturation of industrial catalysis through the lens of ether synthesis, we can trace the conceptual and technological lineage connecting early chemical manufacturing to cutting-edge therapeutic interventions that manipulate biological systems through catalytic principles.

Historical Foundations of Industrial Catalysis

The systematic application of catalysis in industrial processes began in the mid-18th century, with the first documented industrial use of a catalyst occurring in 1746 by J. Roebuck in the manufacture of lead chamber sulfuric acid [11]. This pioneering application established the foundational principle that catalysts could dramatically accelerate chemical transformations without being consumed in the process. For the following century and a half, industrial processes primarily relied on pure components as catalysts, but after 1900, multicomponent catalysts emerged and have since become standard in industrial applications [11]. This evolution reflected growing sophistication in understanding catalytic mechanisms and structure-activity relationships.

The development of porous materials with catalytic properties further advanced the field. Natural zeolites (aluminosilicate minerals with highly ordered pores) were first identified in 1756 by Swedish mineralogist Axel Fredrick Cronstedt, who observed their unique property of releasing steam upon heating—a phenomenon we now recognize as water desorbing from zeolitic pores [12]. However, it wasn't until the 20th century that synthetic zeolites emerged, with Richard Barrer establishing the field of modern synthetic zeolite research in the 1940s [12]. Robert M. Milton's subsequent work at Union Carbide demonstrated zeolites' potential as hydrocarbon cracking catalysts, leading to their industrial adoption by 1959 [12]. The parallel development of charcoal-based adsorption systems, with origins dating back to ancient Egyptian medical practices documented in the Ebers papyrus (circa 1500 BC), provided additional foundational knowledge about porous materials that would inform future catalytic system design [12].

Table 1: Key Historical Developments in Industrial Catalysis

| Year | Development | Key Figure/Company | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1746 | First industrial catalytic process | J. Roebuck | Lead chamber sulfuric acid production |

| 1756 | Discovery of natural zeolites | Axel Fredrick Cronstedt | Identification of porous aluminosilicates |

| 1862 | First synthetic zeolites (lévyne) | Henri Sainte-Claire-Deville | Proof that zeolites could be synthesized |

| 1900+ | Multicomponent catalysts | Various | Enhanced activity and selectivity |

| 1940s | Modern synthetic zeolite research | Richard Barrer | Systematic study and development |

| 1959 | Zeolite Y hydrocarbon isomerization | Union Carbide | Commercial application in petroleum industry |

The economic drivers behind catalytic innovation cannot be overstated. As noted in historical analyses, "If a company's catalyst is not continually improved, another company can make progress in research on that particular catalyst and gain market share" [11]. This competitive pressure fueled rapid advancement in catalytic technologies throughout the 20th century, with catalysts becoming increasingly sophisticated in their composition and application specificity. The professionalization of catalytic chemistry and engineering during this period established catalysis as a distinct scientific discipline bridging fundamental research and industrial application.

Ether Synthesis: The Prototypical Industrial Catalytic Process

Acid-Catalyzed Dehydration of Alcohols

The acid-catalyzed dehydration of alcohols to form ethers represents one of the most historically significant applications of industrial catalysis. This process is particularly valuable for producing symmetrical ethers from primary alcohols, with the synthesis of diethyl ether from ethanol serving as the classic example [13]. Industrially, this transformation is achieved by heating ethanol to 130-140°C in the presence of strong acid catalysts, most commonly sulfuric acid, with over 10 million tons of diethyl ether produced annually via this method [13]. The temperature control is critical, as elevation beyond 140-150°C promotes competing elimination pathways, resulting in ethylene formation rather than the desired ether product [13].

The reaction proceeds through a well-defined three-step mechanism that exemplifies fundamental principles of acid catalysis in organic synthesis. First, one equivalent of alcohol undergoes protonation by the acid catalyst to form its conjugate acid, converting the poor hydroxyl leaving group (OH⁻) into a significantly better leaving group (H₂O). Next, a second equivalent of alcohol performs nucleophilic attack at the electrophilic carbon in an SN2 displacement, forming a new C-O bond while displacing water. Finally, deprotonation of the product by another equivalent of solvent or weak base yields the final ether product [13]. This mechanism demonstrates how catalysts function to modify reaction pathways rather than merely accelerating existing ones.

Diagram 1: Acid-catalyzed ether synthesis mechanism

Williamson Ether Synthesis

While the acid-catalyzed approach excels for symmetrical ether production, the Williamson ether synthesis, discovered by Alexander Williamson in 1850, provides a more versatile route to both symmetrical and asymmetrical ethers [14]. This reaction employs an alkoxide ion (RO⁻) as a nucleophile attacking an organohalide electrophile through an SN2 mechanism. The reaction follows a concerted backside attack mechanism where the nucleophile approaches the electrophilic carbon from the opposite side of the leaving group, resulting in inversion of configuration at the reaction center [14].

The scope of the Williamson reaction is remarkably broad, though it functions most effectively with primary alkoxides and primary alkyl halides. Secondary systems suffer from competing elimination reactions, while tertiary systems are generally too prone to side reactions for practical application [14]. Modern innovations have enhanced this classical approach, with microwave-enhanced technology reducing reaction times from 1.5 hours of reflux to just 10 minutes at 130°C while increasing yields from 6-29% to 20-55% [14]. Additionally, high-temperature approaches (300°C and above) using weaker alkylating agents have demonstrated improved selectivity, particularly for industrial-scale production of aromatic ethers like anisole [14].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Industrial Ether Synthesis Methods

| Parameter | Acid-Catalyzed Dehydration | Williamson Ether Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Substrates | Primary alcohols | Primary alkyl halides + alkoxides |

| Ether Type | Symmetrical | Symmetrical and unsymmetrical |

| Key Limitations | Temperature-sensitive, elimination side products | Elimination with secondary/tertiary halides |

| Industrial Scale | >10 million tons/year (diethyl ether) | Widely used but smaller scale specialty ethers |

| Catalyst System | Homogeneous (H₂SO₄) | Homogeneous (alkoxide) or phase-transfer |

| Typical Yield | High for optimized systems | 50-95% (lab), near-quantitative (industrial) |

Alternative Etherification Pathways

Beyond these two primary methods, several specialized ether synthesis routes have been developed to address specific synthetic challenges. For tertiary ethers where Williamson synthesis fails due to elimination predominating, carbocation-mediated approaches offer a viable alternative [15]. By dissolving tertiary alkyl halides in alcohol solvents, leaving group dissociation generates carbocations that are trapped by nucleophilic attack from the alcohol solvent, following a classic SN1 pathway [15]. Similarly, treating alkenes in alcohol solvents with strong acids having poorly nucleophilic counterions generates carbocations via protonation following Markovnikov's rule, with subsequent trapping by alcohol nucleophiles yielding ether products [15].

To circumvent issues of carbocation rearrangements that often plague these approaches, alkoxymercuration provides a valuable alternative [15]. This method involves reacting alkenes with mercury(II) acetate in alcohol solvent, forming a "mercurinium" ion intermediate that undergoes regioselective attack by the alcohol at the more substituted carbon. Subsequent demercuration with sodium borohydride yields the ether product without rearrangement, effectively adding the elements of alcohol across the alkene double bond with Markovnikov selectivity [15].

Experimental Protocols in Catalytic Ether Synthesis

Laboratory-Scale Diethyl Ether Synthesis

The synthesis of diethyl ether via acid-catalyzed dehydration of ethanol serves as a fundamental experiment demonstrating principles of industrial catalysis. The following protocol outlines the standard laboratory procedure:

Materials and Equipment:

- Ethanol (absolute, 200 proof)

- Concentrated sulfuric acid (catalyst)

- Heating mantle with temperature control

- Fractional distillation apparatus

- Separatory funnel

- Anhydrous calcium chloride (drying agent)

- Safety equipment: lab coat, gloves, eye protection, fume hood

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a 500mL round-bottom flask, combine 100mL of absolute ethanol with 100mL of concentrated sulfuric acid slowly with continuous stirring. The addition should be performed in an ice bath to control the exothermic reaction. Equip the flask with a fractional distillation apparatus.

Ether Production: Gradually heat the reaction mixture to 130-140°C using a heating mantle with precise temperature control. Maintain this temperature range throughout the reaction to minimize ethylene formation. The diethyl ether product will distill over as it forms.

Product Collection: Collect the distillate in an ice-cooled receiver. The crude ether will separate into a distinct layer in the receiving flask.

Purification: Transfer the crude ether to a separatory funnel and wash sequentially with:

- 50mL of 10% sodium hydroxide solution (to remove acidic impurities)

- 50mL of saturated sodium chloride solution (to remove water) Dry the ether layer over anhydrous calcium chloride for 30 minutes with occasional stirring.

Final Distillation: Decant the dried ether from the drying agent and perform a final distillation, collecting the fraction boiling at 34-36°C.

Safety Considerations: Diethyl ether is extremely flammable and forms explosive peroxides upon standing. All procedures must be conducted in a fume hood with no ignition sources present. The reaction temperature must be carefully controlled to prevent decomposition or excessive pressure buildup.

Williamson Ether Synthesis Protocol

The Williamson synthesis provides a general method for ether formation, particularly valuable for unsymmetrical ethers:

Materials and Equipment:

- Sodium metal or sodium hydride

- Anhydrous alcohol (ROH)

- Alkyl halide (R'X)

- Anhydrous solvent (e.g., THF, diethyl ether)

- Magnetic stirrer with heating capability

- Nitrogen or argon atmosphere setup

- Standard glassware for reflux and extraction

Procedure:

- Alkoxide Formation: In a flame-dried round-bottom flask under inert atmosphere, add 50mL of anhydrous solvent and 0.1 mol of sodium metal or sodium hydride. Slowly add 0.1 mol of the anhydrous alcohol with stirring, allowing hydrogen gas evolution to complete. Continue stirring until a homogeneous solution forms.

Alkylation: Add 0.1 mol of alkyl halide dropwise to the alkoxide solution. Heat the reaction mixture to reflux (typically 50-100°C) for 1-8 hours, monitoring reaction completion by TLC or GC.

Workup: Cool the reaction mixture to room temperature and carefully quench with water. Extract the product with diethyl ether (3 × 30mL), combine the organic extracts, and dry over anhydrous magnesium sulfate.

Purification: Remove solvents by rotary evaporation and purify the crude product by distillation or column chromatography as appropriate.

Modifications for Industrial Application: Industrial Williamson syntheses often employ phase-transfer catalysts (e.g., tetrabutylammonium bromide) to enhance reaction rates. For challenging substrates, soluble iodide salts may be added to catalyze the reaction through in situ halide exchange (Finkelstein reaction), generating more reactive iodide intermediates from chloride starting materials [14].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Catalytic Ether Synthesis

| Reagent/Catalyst | Function | Application Specifics | Safety Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfuric Acid | Brønsted acid catalyst | Dehydration of primary alcohols to symmetrical ethers (130-140°C) | Highly corrosive, causes severe burns |

| p-Toluenesulfonic Acid | Mild organic acid catalyst | Ether formation under milder conditions | Less corrosive than mineral acids |

| Sodium/Potassium Alkoxides | Strong base/nucleophile | Williamson synthesis with primary alkyl halides | Moisture-sensitive, flammable |

| Phase-Transfer Catalysts | Facilitate interphase transfer | Enhance reaction rates in biphasic systems | Generally low toxicity |

| Mercury(II) Acetate | Electrophilic mercury source | Alkoxymercuration of alkenes | Highly toxic, requires special disposal |

| Sodium Borohydride | Reducing agent | Demercuration step in alkoxymercuration | Moisture-sensitive, hydrogen gas evolution |

The Catalyst-Mediated Medical Revolution

Foundations of Catalytic Medicine

The principles governing industrial catalytic processes have transcended their origins in chemical manufacturing to establish entirely new paradigms in therapeutic intervention. This transition represents a conceptual bridge between traditional catalysis and emerging biomedical applications, where synthetic catalysts operate within biological systems to correct pathological processes. The field of catalysis medicine embodies this approach, utilizing "man-made catalysts as therapeutics" that directly participate in the chemical networks of living organisms [16]. This represents a fundamental shift from conventional pharmacology, moving beyond receptor-ligand interactions to actively modify biochemical pathways through catalytic intervention.

The theoretical foundation of catalysis medicine rests upon viewing living organisms as complex networks of chemical reactions, where disorders stemming from dysregulated enzymes can be treated by chemical catalysts that bypass these compromised biological catalysts [16]. This approach offers unique advantages, including the potential to address genetic diseases without genetic manipulation, introduce non-natural modifications that may be superior to natural enzymatic products, and create persistent therapeutic effects through stable chemical modifications not subject to biological regulation [16]. The development of catalysts for biomedical applications must satisfy stringent requirements, including operation under physiological conditions (aqueous solvent, body temperature, neutral pH), exceptional selectivity for target biomolecules with residue-level resolution, and appropriate ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) profiles [16].

Nanocatalytic Medicine: Industrial Principles in Therapeutic Applications

The convergence of industrial catalysis with nanotechnology has spawned the emerging field of nanocatalytic medicine, which applies nanocatalytic approaches to resolve medical problems [17]. This discipline systematically leverages knowledge from industrial catalytic processes to design therapeutic interventions that catalyze specific reactions within biological systems. The parallels between industrial and medical catalysis are striking, though significant adaptations are required to accommodate the drastic differences in operating conditions between chemical plants and physiological environments.

Diagram 2: Translation of industrial catalysis to medical applications

Several categories of industrial catalytic reactions have demonstrated particular promise for biomedical translation:

Fenton/Fenton-like Catalysis: Originally developed for environmental applications like wastewater purification and soil remediation, Fenton chemistry utilizes catalysts (typically Fe²⁺ or Cu²⁺) to decompose hydrogen peroxide into highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (·OH) [17]. The biomedical application capitalizes on the elevated hydrogen peroxide and lactic acid concentrations in tumor microenvironments, employing Fenton nanocatalysts like iron nanoparticles to selectively generate cytotoxic hydroxyl radicals within tumors while sparing healthy tissues [17]. This approach represents a direct translation of industrial oxidation chemistry to therapeutic ablation of pathological tissues.

Acid/Base Catalysis: Industrial acid catalysts like sulfuric acid (used in cellulose hydrolysis for bioethanol production) and base catalysts like NaOH (employed in biodiesel production via transesterification) have inspired the development of biomedical catalysts capable of similar transformations under physiological conditions [17]. Zeolites, widely used in crude oil processing and petrochemistry under harsh conditions, demonstrate potential as both drug carriers and therapeutic catalysts when engineered as nanoparticles [17]. Similarly, polyoxometalates (POMs) containing multivalent transition metal ions exhibit acid-responsive assembly behavior and enzyme-like catalytic activity with applications in anti-bacterial, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer therapies [17].

Transition Metal Catalysis: Industrial processes employing transition metals (e.g., Fe, Ni, Pd, Pt) and their oxides for redox reactions have informed the development of functional therapeutic agents [17]. For instance, transition metal nanoparticles can catalyze the in situ generation of therapeutic agents within pathological environments. Palladium and iron nanoparticles have been developed for tumor-targeted hydrogen delivery, leveraging their catalytic activity to modulate redox homeostasis in cancer cells [17]. The enhanced catalytic activity observed at nanoscale dimensions due to increased surface area and defect density makes nanomaterials particularly attractive for these applications.

Experimental Framework for Catalytic Medicine

The translation of catalytic principles from industrial chemistry to medical applications requires specialized experimental approaches that account for the unique challenges of biological systems:

In Vivo Catalyst Evaluation Protocol:

Materials:

- Functionalized nanocatalyst (e.g., tumor-targeting moieties)

- Animal disease model (e.g., tumor-bearing mice)

- Appropriate analytical techniques (HPLC, MS, imaging)

- Control groups (untreated, catalyst-only, substrate-only)

Procedure:

- Catalyst Administration: Administer the therapeutic catalyst via appropriate route (IV, IP, etc.) at predetermined dosage based on preliminary toxicity studies.

Substrate Delivery: If required, deliver catalyst substrate (e.g., H₂O₂ for Fenton catalysts) either simultaneously or sequentially based on reaction kinetics.

Biodistribution Analysis: Quantify catalyst accumulation in target tissues versus non-target organs using appropriate imaging or analytical techniques.

Therapeutic Assessment: Monitor disease progression/regression using established biomarkers, imaging modalities, and histological analysis.

Safety Evaluation: Assess potential off-target effects through comprehensive blood chemistry, histopathology of major organs, and behavioral observations.

Case Study: Epigenetic Modulation via Synthetic Catalysts

A compelling example of catalysis medicine involves the development of chemical catalysts for epigenetic modulation. Researchers have created synthetic catalysts that directly acylate histone proteins in living cells, complementing or bypassing endogenous enzymatic activities [16]. For instance, the DMAP-SH (DSH) catalyst promotes regioselective acylation at specific lysine residues using physiological acetyl donors like acetyl-CoA [16]. When conjugated with targeting ligands like LANA (which binds histone acidic patches), these catalysts achieve remarkable selectivity—LANA-DSH catalyzes acetylation at H2BK120 with approximately 90% yield in mononucleosome systems [16].

This catalytic approach to epigenetic modification demonstrates several advantages over conventional small-molecule enzyme inhibitors: (1) it can introduce persistent epigenetic marks not subject to natural erasure mechanisms; (2) it enables incorporation of non-natural acyl groups simply by providing alternative acyl donors; and (3) it can compete with pathological enzymatic activities, as demonstrated by synthetic acetylation at H2BK120 suppressing the pro-leukemic ubiquitination at the same residue [16]. This final application represents a promising strategy for treating mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL)-rearranged leukemia, demonstrating the therapeutic potential of catalytic epigenetic interventions.

The historical trajectory from industrial ether synthesis to contemporary catalytic medicine illustrates a fundamental paradigm in technological evolution: principles refined in industrial contexts frequently transcend their original applications to enable transformative advances in seemingly unrelated fields. The catalytic strategies developed for efficient ether production—including acid catalysis, nucleophilic displacement, and regioselective addition—have established conceptual frameworks that now inform therapeutic interventions at the molecular level. This intellectual and methodological migration between chemical engineering and biomedical science exemplifies the interdisciplinary nature of modern scientific progress.

As catalytic medicine continues to evolve, principles honed through decades of industrial catalyst optimization—including structure-activity relationships, kinetic optimization, and catalyst stabilization—will undoubtedly accelerate its development. Similarly, emerging challenges in catalytic medicine, such as achieving precise targeting in complex biological environments and minimizing off-target activity, may inspire innovations that feedback into industrial catalytic processes. This continuous cross-pollination between industrial chemistry and therapeutic science ensures that the legacy of early catalytic advances, including ether synthesis, will extend far beyond their original applications to address increasingly complex challenges at the interface of chemistry, materials science, and medicine.

The 19th century marked a transformative period for catalysis, shifting it from an unexplained chemical art to a formal scientific discipline. Prior to this era, catalytic processes such as fermentation, soap making, and ether production were employed without a theoretical understanding of the underlying mechanisms [3] [18]. This paper examines the pivotal 19th-century developments that established the terminology, theoretical frameworks, and kinetic principles of catalysis, providing the foundation for all subsequent catalytic science and its immense applications in modern industry, including drug development.

The conceptualization of catalysis required a move from purely empirical observations to systematic, quantitative experimentation. This was facilitated by the period's burgeoning interest in reaction velocities, energy, and molecular dynamics—key concerns of the emerging field of physical chemistry [18]. The work of several key scientists, culminating in the award of the Nobel Prize to Wilhelm Ostwald in 1909, successfully defined the core principles that distinguished catalytic action from other chemical phenomena [19].

The Pre-Scientific Landscape of Catalytic Practices

Long before the term "catalysis" was coined, human industry unconsciously relied on catalytic processes. The production of wine, beer, soap, and cheese involved biochemical catalysts whose modes of action remained a mystery [3] [18]. A significant early medicinal achievement was Valerius Cordus's 1552 synthesis of ether using sulfuric acid as a catalyst, which revolutionized surgery by introducing a reliable anaesthetic [3]. These processes were effectively the "alchemy" of their time—practical arts without a coherent scientific theory [3].

The early industrial era also saw the application of catalytic-type processes. The lead chamber process for producing sulfuric acid, which utilized nitrogen oxides to catalyze the oxidation of sulfur dioxide, was a forerunner to more sophisticated catalytic industrial methods [18]. However, these applications were developed through trial and error, lacking the predictive power that a fundamental theory would provide.

Foundational Experiments and the Birth of a Concept

The early 19th century witnessed a series of critical experiments that isolated and highlighted the peculiar phenomenon that would become known as catalysis. Table 1 summarizes the key quantitative observations from these foundational studies.

Table 1: Key 19th Century Experimental Observations Preceding Formalization

| Investigator(s) | Year(s) | System Studied | Key Catalytic Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gottlieb Kirchhoff | Early 19th C. | Starch and Sugar | Acids enhanced the conversion of starch to sugar [18]. |

| Sir Humphry Davy | ~1812-1817 | Gaseous Combustion | Platinum hastened the combustion of a variety of gases [18]. |

| Multiple Scientists | Early 19th C. | Hydrogen Peroxide | Stability in acid, but decomposition in presence of alkali & metals (Mn, Ag, Pt, Au) [18]. |

| Michael Faraday | 1834 | Hydrogen/Oxygen Recombination | A clean platinum plate promoted gas recombination; activity suppressed by ethylene/CO [18]. |

| P. Phillips | 1830s | SO₂ Oxidation | Patented use of platinum to oxidize SO₂ to SO₃; process abandoned due to catalyst poisoning [18]. |

These experiments shared a common thread: the acceleration or modification of a chemical reaction by a substance that itself remained unaltered. Sir Humphry Davy's work was particularly insightful, as he recognized the importance of a clean metallic surface, a concept that would later become central to heterogeneous catalysis and the understanding of catalyst poisons [18]. Similarly, Michael Faraday's meticulous study of the platinum-induced recombination of hydrogen and oxygen provided clear evidence that the catalytic activity could be suppressed by the presence of other gases, suggesting a competitive process at the metal's surface [18].

The Formal Coining of Terminology: Berzelius and Ostwald

In 1835, the renowned Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius synthesized these disparate observations into a single unifying concept. He derived the term catalysis from the Greek words kata- (down) and lyein (loosen) [18] [20]. Berzelius postulated the existence of a special "catalytic force" to explain the ability of certain substances to awaken the "slumbering affinities" of bodies by their mere presence [18].

While Berzelius's "force" was a metaphysical construct, it successfully categorized a genuine class of chemical behavior. The term itself, however, endured. The subsequent development of chemical kinetics in the latter half of the 19th century, notably by J.H. van 't Hoff and Svante Arrhenius, provided the tools to move beyond Berzelius's formulation [18] [19]. The Arrhenius equation, which quantitatively links reaction rate to temperature, became a cornerstone for describing catalytic reactions [19].

It was Wilhelm Ostwald, a founder of physical chemistry, who delivered the modern, kinetic definition of a catalyst. In 1901, he stated, "A catalyst is a material that changes the rate of a chemical reaction without appearing in the final product" [19]. His systematic and quantitative investigations led to a profound understanding that catalysis was a kinetic phenomenon, not the result of a mysterious force. For this work, Ostwald was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1909, an accolade that cemented catalysis's place in mainstream science [19].

The Ostwald Workflow: From Observation to Kinetic Formalization

The following diagram illustrates the logical progression of thought, from early empirical observations to Ostwald's kinetic formalization of catalysis, which critically displaced the earlier concept of a "catalytic force."

Core Theoretical Principles Established in the 19th Century

The experimental and theoretical work of the 19th century culminated in the establishment of several non-negotiable principles that define catalytic action to this day.

The Principle of Kinetic Acceleration and the Activation Energy Barrier

The primary function of a catalyst is to accelerate the rate of a chemical reaction. The modern understanding is that catalysts provide an alternative reaction pathway with a lower activation energy (Ea) than the non-catalyzed mechanism [20]. This principle is visually summarized in the energy profile diagram below, which contrasts the reaction pathways with and without a catalyst.

The Invariance of Thermodynamic Equilibrium

A cornerstone principle solidified by the work of Ostwald and others is that a catalyst does not affect the position of a chemical reaction's equilibrium [18] [20]. A catalyst only increases the rate at which equilibrium is attained. This is a direct consequence of chemical thermodynamics. Since a catalyst is regenerated at the end of the reaction cycle, it cannot change the free energy difference between reactants and products, which is the sole determinant of equilibrium [20]. This principle was elegantly demonstrated by Georges Lemoine (1877), who showed that the decomposition of hydriodic acid reached the same equilibrium point at 350°C, regardless of whether a platinum sponge catalyst was present [18].

The Catalyst Cycle and Regeneration

The 19th century saw the recognition of the catalytic cycle, in which the catalyst interacts with reactants to form intermediates but is regenerated in its original form at the end of the cycle [18] [20]. This is why only a small amount of catalyst is needed to transform a large quantity of reactants. A classic gas-phase example studied in this period was the nitric oxide-catalyzed oxidation of sulfur dioxide to sulfur trioxide [20].

Experimental Protocols of Landmark Studies

The formalization of catalysis relied on quantitative, reproducible experiments. The following methodologies were critical in shaping the theoretical understanding.

Protocol: Lemoine's Equilibrium Experiment (1877)

Objective: To demonstrate that a catalyst affects the reaction rate but not the final equilibrium position [18].

- Apparatus Setup: Prepare a sealed, temperature-controlled reaction vessel capable of withstanding high pressure. Incorporate sampling ports for periodic analysis.

- Reaction Preparation: Introduce a known quantity of hydriodic acid (HI) gas into the vessel.

- Control Experiment: Heat the vessel to a constant temperature of 350°C. Periodically sample the gas mixture and analyze the composition (e.g., via titration or density measurement) to determine the extent of the decomposition reaction 2HI ⇌ H₂ + I₂. Monitor until the composition remains constant, indicating equilibrium has been reached. Record the final equilibrium constant and the time taken to reach equilibrium.

- Catalyzed Experiment: Repeat Step 2. Introduce a small, known mass of platinum sponge catalyst into the reaction vessel. Heat the system to the same constant temperature of 350°C. Sample and analyze the gas mixture periodically as in Step 3.

- Data Analysis: Compare the time taken to reach equilibrium in the control versus the catalyzed experiment. Confirm that the final equilibrium concentrations of HI, H₂, and I₂ are identical in both experiments, regardless of the presence of the catalyst.

Protocol: Faraday's Surface Catalysis Experiment (1834)

Objective: To investigate the role of a clean metal surface in catalyzing gas recombination and the effect of inhibitor gases [18].

- Electrolysis: Use electrolysis of water to produce pure hydrogen and oxygen gases.

- Surface Preparation: Obtain a polished platinum plate. Clean the surface meticulously (e.g., with acid and heat) to ensure it is free of contaminants.

- Initial Observation: In a controlled atmosphere, expose the clean platinum plate to a mixture of hydrogen and oxygen. Observe the recombination into water (e.g., via formation of mist or temperature change on the surface).

- Introduction of Inhibitor: Introduce a small amount of a potential inhibitor gas, such as ethylene (C₂H₄) or carbon monoxide (CO), into the hydrogen-oxygen mixture.

- Comparative Analysis: Observe and record the marked decrease or complete cessation of the recombination reaction upon the introduction of the inhibitor gas.

- Conclusion: The experiment demonstrates that a clean surface is essential for this catalytic reaction and that other gases can compete for active sites, effectively "poisoning" the catalyst.

The 19th Century Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials in 19th Century Catalysis Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Research |

|---|---|

| Platinum Sponge/Metal | A versatile, high-surface-area heterogeneous catalyst for studying gas-phase reactions like oxidations and hydrogenations [18]. |

| Sulphuric Acid (H₂SO₄) | A common homogeneous acid catalyst used in reactions like esterification and the inversion of cane sugar [18]. |

| Nitrogen Oxides (NO, NO₂) | Catalysts for the lead chamber process and the oxidation of SO₂, serving as an early example of gas-phase homogeneous catalysis [18]. |

| Cane Sugar Solution | A model reactant for studying acid-catalyzed hydrolysis ("inversion"), with reaction progress easily monitored by measuring optical rotation [18]. |

| Hydriodic Acid (HI) Gas | The reactant in Lemoine's landmark equilibrium experiment to prove catalysts do not shift thermodynamic equilibrium [18]. |

The 19th century represents the definitive period of formalization for catalytic science. The journey from Berzelius's coining of the term "catalysis" and his postulate of a mysterious force to Ostwald's precise, kinetic-based definition marked a paradigm shift. The establishment of core principles—that catalysts operate by providing a lower-energy pathway, that they remain unchanged after the reaction, and that they cannot alter thermodynamic equilibrium—created a robust theoretical framework. This framework not only explained existing chemical phenomena but also empowered the deliberate design of catalytic processes in the 20th century, such as the Haber-Bosch process and catalytic cracking, which have profoundly shaped the modern world, including the field of pharmaceutical development. The 19th-century foundation turned catalysis from an art into a science, enabling its future as a discipline central to chemical innovation.

The development of catalysts represents a pivotal thread throughout human history, from ancient enzymatic processes to modern synthetic chemistry. Within this continuum, periods of conflict have consistently served as potent accelerants for technological innovation. The Haber-Bosch process, developed in the early twentieth century, stands as a paradigm of war-driven innovation that permanently altered global agriculture, industrial chemistry, and strategic military logistics. This whitepaper examines the Haber-Bosch process as a quintessential example of how catalytic science, propelled by strategic necessity, can generate transformative technological pathways with enduring societal impact. We analyze the technical parameters, experimental breakthroughs, and industrial implementation of this process, providing researchers and scientists with a detailed examination of its catalytic mechanisms and historical significance.

The Haber-Bosch Process: Technical Analysis

Historical Context and Strategic Imperative

Prior to the Haber-Bosch process, the world faced an impending nitrogen crisis. Natural nitrogen sources, primarily Chilean saltpeter deposits and guano, were being rapidly depleted amid growing demand for fertilizers and explosives [21]. By 1900, Chile produced two-thirds of the world's fertilizer, creating strategic vulnerabilities for nations dependent on these imports [21]. Germany, in particular, faced acute food security challenges due to poor soil quality and lacked a colonial empire for accessing natural nitrate deposits [21]. The German government recognized that without a new, economical method for ammonia synthesis, the nation would face both agricultural shortfalls and military vulnerability. This strategic imperative catalyzed intensive research into atmospheric nitrogen fixation, culminating in the Haber-Bosch process [21] [22].

Table 1: Pre-Haber Nitrogen Sources and Limitations

| Nitrogen Source | Annual Production (circa 1900) | Primary Limitations | Strategic Vulnerabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chilean Saltpeter | 350,000-900,000 tonnes (German imports) | Finite deposits, oligopoly control, rising costs | Naval blockade susceptibility, supply concentration |

| Guano Deposits | 12.5 million tons (total exhausted) | Completely depleted by late 19th century | Resource exhaustion, transportation challenges |

| Ammonia By-Product from Coke Production | Limited and insufficient for demand | Could not meet growing agricultural/military needs | Production capacity constraints |

| Birkeland-Eyde Process | 12,000 tonnes (1913) | Extremely high electricity consumption | Geographic constraints, energy intensive |

Fundamental Chemical Principles and Thermodynamics

The Haber-Bosch process synthesizes ammonia from elemental hydrogen and nitrogen through the following equilibrium reaction [23]:

N₂ + 3H₂ ⇌ 2NH₃ ΔH°₂₉₈K = -92.28 kJ/mol

This exothermic reaction presents significant thermodynamic challenges: while lower temperatures favor ammonia formation, they dramatically slow reaction kinetics. Additionally, the reaction results in a decrease in gas molecules (from 4 to 2), meaning higher pressures shift equilibrium toward ammonia production [23]. The triple bond in molecular nitrogen (N≡N) requires substantial energy to break, with a dissociation energy of 945 kJ/mol, creating a formidable activation barrier [23]. These competing factors necessitated precise optimization of temperature, pressure, and catalytic surfaces to achieve economically viable reaction rates and yields.

Table 2: Thermodynamic and Process Parameters for Ammonia Synthesis

| Parameter | Early Haber Process (1909) | Modern Industrial Process | Impact on Equilibrium & Kinetics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 550°C | 400-500°C | Higher temperatures increase rate but decrease equilibrium constant |

| Pressure | 175 atm | 150-300 atm | Higher pressures favor ammonia formation (fewer gas molecules) |

| Single-Pass Conversion | ~15% | ~15-20% | Limited by equilibrium; recycling enables >97% overall yield |

| Catalyst | Osmium/Uranium | Promoted Iron Catalyst | Lowers activation energy from ~420 kJ/mol to ~160 kJ/mol |

Catalyst Development and Experimental Protocols

The development of effective catalysts represented the most critical experimental challenge for the Haber-Bosch process. Fritz Haber's initial investigations employed osmium and uranium catalysts, which demonstrated sufficient activity but presented practical limitations due to scarcity and sensitivity [22]. The systematic investigation of alternative catalysts fell to Alwin Mittasch at BASF, who conducted approximately 20,000 screening experiments between 1909 and 1912 to identify an economically viable and highly active catalyst system [22].

Experimental Protocol: Catalyst Screening and Testing (Mittasch, 1909-1912)

- Catalyst Preparation: Various metal oxides (primarily iron-based) were mixed with promoters including K₂O, CaO, SiO₂, and Al₂O₃ in precise stoichiometric ratios

- Pre-treatment: Catalysts were subjected to reduction under hydrogen atmosphere at elevated temperatures (400-500°C) to activate the metallic surfaces

- Reaction Testing: Small-scale high-pressure reactors constructed of forged steel operated at 175-200 atm and 500-600°C

- Performance Evaluation: Ammonia concentration in effluent gases measured by absorption in standardized acid solutions followed by titration

- Lifetime Testing: Continuous operation over hundreds of hours to assess catalyst stability and resistance to poisoning

- Characterization: Surface area measurements, crystallinity assessment, and microscopic examination of spent catalysts [22] [23]

This exhaustive experimental campaign yielded the promoted iron catalyst (primarily Fe₃O₄ with Al₂O₃, K₂O, and CaO promoters) that remains the industrial standard today. The alumina (Al₂O₃) structural promoter prevents sintering of iron crystallites at operating temperatures, while potassium oxide (K₂O) electronic promoter facilitates nitrogen dissociation by enhancing electron donation to antibonding orbitals of N₂ [23].

Engineering Challenges and Reactor Design Innovations

Carl Bosch's scale-up of Haber's laboratory process confronted monumental engineering challenges, particularly in reactor design and materials science. Early reactors failed catastrophically due to hydrogen embrittlement—a phenomenon where hydrogen atoms diffuse into steel, reacting with carbon to form methane and creating brittle fissures [22]. Bosch's engineering breakthrough was the development of a double-walled reactor featuring a low-carbon steel liner surrounded by a high-strength pressure-bearing shell [22].

Reactor Design Protocol (Bosch, 1910-1913)

- Material Selection: Development of specialized chromium-tungsten steel alloys resistant to hydrogen permeation

- Liner Implementation: Thin soft steel liner inside pressure vessel to absorb hydrogen diffusion

- Pressure Relief System: Strategic perforations in outer shell allowing diffused hydrogen to escape safely

- Internal Heating: Novel internal heating elements avoiding external temperature gradients that create stress concentrations

- Safety Systems: Rapid-acting safety valves and emergency pressure relief systems enabling shutdown within seconds

- Process Instrumentation: Custom-designed temperature, pressure, and gas composition monitoring systems where none previously existed [22]

This reactor design, coupled with progressive improvements in compressor reliability and heat exchanger efficiency, enabled the first industrial-scale Haber-Bosch plant to commence operation at BASF's Oppau facility in 1913, producing 20 tonnes of ammonia daily by 1914 [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Ammonia Synthesis Research

| Reagent/Material | Composition/Type | Function | Historical Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Formulations | Fe₃O₄ promoted with Al₂O₃, K₂O, CaO, SiO₂ | Lowers activation energy for N₂ dissociation; ~160 kJ/mol vs ~420 kJ/mol uncatalyzed | Mittasch's 20,000 tested formulations [22] |

| High-Pressure Reactor | Forged steel with double-wall construction | Contains reaction at 150-300 atm; prevents hydrogen embrittlement | Bosch's lined reactor design [22] |

| Synthesis Gas | 3:1 H₂:N₂ mixture, purified from S, O₂, CO contaminants | Feedstock; purity critical to prevent catalyst poisoning | Water-gas shift process developed by BASF [22] |

| Promoters | K₂O (electronic), Al₂O₃ (structural) | Enhance activity and stability of iron catalyst | Alwin Mittasch systematic promoter studies [23] |

| Temperature Control | External/internal heating with precise thermocouples | Maintains optimal 400-500°C operating temperature | Novel internal heating elements by Bosch [22] |

Impact and Legacy: From Warfare to Global Food Security

The Haber-Bosch process yielded immediate strategic impacts during World War I, enabling Germany to produce explosives despite the Allied naval blockade that cut off Chilean saltpeter imports [21] [22]. By 1914, Germany's synthetic ammonia capacity provided the essential precursor for nitric acid production, extending the war by an estimated two years according to some historians [21].

The long-term agricultural impacts proved even more profound. Modern analysis indicates that approximately 50% of the nitrogen in human tissues originates from Haber-Bosch synthesis, and the process supports nourishment for an estimated two billion people worldwide [21]. The process fundamentally transformed global agriculture, enabling the development of nitrogen-based fertilizers that underpin intensive farming practices [22].

Contemporary research continues to refine the Haber-Bosch paradigm while exploring complementary approaches. Current investigations include electrocatalytic reduction of nitrogen, photocatalytic systems, plasma-catalytic processes, and biomimetic approaches inspired by nitrogenase enzymes [24]. These emerging technologies aim to decentralize ammonia production and integrate it with renewable energy sources, potentially enabling more sustainable nitrogen management in the 21st century [24].

The development of the Haber-Bosch process exemplifies how strategic imperatives, particularly during conflict, can accelerate fundamental technological breakthroughs. This analysis demonstrates how simultaneous innovations in catalytic science, materials engineering, and process design converged to solve a critical societal challenge. For contemporary researchers and drug development professionals, this historical case study offers enduring lessons about multidisciplinary collaboration, systematic experimental methodology, and the translation of laboratory discoveries to industrial-scale implementation. As catalytic science continues to evolve, the Haber-Bosch process remains a paradigm of how targeted investment in fundamental chemical research can yield transformative impacts across multiple domains of human endeavor.

The emergence of extractive metallurgy represents a pivotal technological revolution in human history, marking a fundamental transition from the Stone Age to metal ages and laying the foundational principles for materials science and catalyst development. This whitepaper examines the pyrometallurgical processes of early copper smelting through the lens of modern analytical techniques, focusing specifically on the analysis of 5,000-year-old slag remains. These vitrified waste materials serve as geochemical archives that encode critical information about ancient technological capabilities, material choices, and process efficiencies.

Within the broader context of catalyst development history, ancient metallurgy represents humanity's first deliberate manipulation of chemical processes at elevated temperatures—a precursor to modern heterogeneous catalysis. The high-temperature reactions involved in transforming copper minerals into metal required sophisticated understanding of redox chemistry, phase separation, and reaction kinetics that parallel fundamental concepts in contemporary catalyst synthesis and optimization. Recent advances in non-destructive analytical methods, particularly X-ray computed tomography (CT), have revolutionized our ability to decode these ancient materials without compromising their structural integrity, offering new insights into humanity's earliest forays into materials engineering [25].

Background: The Dawn of Extractive Metallurgy

Historical Context and Chronology

The development of copper metallurgy occurred independently across multiple regions, with current evidence pointing to early experimentation in the Balkans around 5000 BC and organized production in Iran by approximately 3000 BC [26]. This technological revolution emerged from centuries of prior experience with copper minerals used for beads and pigments, gradually evolving toward pyrometallurgical extraction. The Vinča culture site of Belovode in Serbia has provided the earliest securely dated evidence of copper smelting, with slag droplets dating to c. 5000 BC, challenging traditional models of a single Near Eastern origin for extractive metallurgy [26].

The technological progression moved from cold-hammering of native copper to deliberate smelting of oxide and carbonate ores, and eventually to the processing of more complex sulfide minerals. This evolution required increasingly sophisticated furnace designs and process control, representing a remarkable development in human engineering capability. By the Early Bronze Age (approximately 3100-2900 BCE), sites like Tepe Hissar in Iran demonstrated specialized metal production within societies engaged in long-distance trade and highly organized social structures [25] [27].

Significance of Slag in Archaeometallurgy

Slag, the vitrified waste material produced during smelting, provides the most abundant and informative remnant of ancient metallurgical processes. These chemically complex byproducts form when siliceous gangue minerals from the ore combine with fluxing materials to separate from the molten metal. The mineralogical composition and internal microstructure of slag preserve a record of furnace conditions, raw materials, and technological choices [28].

As Antoine Allanore, professor of metallurgy at MIT, explains: "Even though slag might not give us the complete picture, it tells stories of how past civilizations were able to refine raw materials from ore and then to metal. It speaks to their technological ability at that time, and it gives us a lot of information" [25]. The study of slag remains essential for reconstructing the chaîne opératoire of ancient metal production, from ore selection and beneficiation to smelting and metal refinement.

Analytical Approaches to Ancient Slag

Traditional Characterization Methods

Prior to the advent of advanced imaging techniques, researchers relied on a suite of destructive analytical methods to characterize ancient slags. These approaches remain valuable for generating precise chemical and mineralogical data, typically applied after careful visual examination and sampling.

Table 1: Traditional Analytical Methods for Slag Characterization

| Method | Application | Information Obtained | Sample Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optical Microscopy | Examination of microstructure and phase distribution | Presence of copper prills, gas cavities, mineral phases, and crystallinity | Polished sections, destructive |

| X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) | Bulk elemental composition | Major and minor elements (Cu, Fe, Si, Ca, etc.) | Powdered or solid, minimal preparation |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDX) | High-magnification imaging and microchemical analysis | Phase composition, elemental mapping, inclusion characterization | Polished sections, conductive coating |

| X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) | Mineralogical phase identification | Crystalline phases (e.g., fayalite, magnetite, hercynite) | Powdered, minimal sample mass |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) | Trace element analysis | Low-concentration elements, isotopic ratios for provenance | Acid-digested, destructive |

These traditional methods have revealed that ancient copper slags are typically dominated by fayalite (Fe₂SiO₄) and magnetite (Fe₃O₄) crystal phases in a glassy matrix, with embedded droplets of copper or copper-arsenic alloy [28]. The presence of these phases indicates smelting temperatures exceeding 1200°C and controlled oxygen partial pressures to facilitate the reduction of copper oxides to metal while maintaining iron in silicate forms.

X-Ray Computed Tomography: A Non-Destructive Revolution

The recent application of industrial CT scanning to archaeometallurgical research represents a paradigm shift in non-destructive analysis. Originally developed for medical imaging, this technique generates high-resolution 3D models of the internal structure of slag samples, revealing features invisible to external examination [25] [27].

MIT researchers demonstrated this approach on slag from Tepe Hissar (3100-2900 BCE), using CT scanning to identify internal microstructures such as pores, cracks, metallic prills, and mineral inclusions before any destructive sampling [25]. This allows for precise targeting of subsequent analytical techniques and preserves the structural context of microsampling locations. As Benjamin Sabatini, a postdoc involved in the MIT study, noted: "The CT scanning shows you exactly what is most interesting, as well as the general layout of things you need to study" [25].

The CT scanning process involves rotating the sample while capturing multiple X-ray projections, which are computationally reconstructed into cross-sectional slices. These slices can be assembled into 3D visualizations that map variations in material density and composition, effectively creating a digital archive of the sample's internal geometry [27].

Diagram 1: CT Scanning and Analysis Workflow for Ancient Slag

Case Study: Tepe Hissar Slag Analysis

Archaeological Context and Sample Description

Tepe Hissar, located in northern Iran, was a major center of Early Bronze Age metalworking during the period of 3100-2900 BCE [27]. The site represents one of the earliest examples of organized metallurgy within a society engaged in long-distance trade and specialized craftsmanship. Slag samples from this site, loaned by the Penn Museum to MIT researchers in 2022, provided the material for the pioneering CT scanning study [25].

The slag samples exhibit heterogeneous composition, with some fragments containing visible copper prills while others show no metallic copper, creating puzzles about the exact smelting processes employed. Previous studies had also identified variable arsenic content in Tepe Hissar materials, leading to debates about whether arsenical copper was an intentional product or incidental result of the ore sources [25] [27].

Integrated Analytical Methodology

The MIT research team employed a complementary analytical approach, combining non-destructive CT scanning with targeted traditional methods:

- Initial CT scanning using industrial and medical scanners to map internal structures

- Identification of regions of interest including copper droplets, gas voids, and unusual inclusions

- Targeted sectioning of samples based on CT data

- Traditional analysis of sectioned samples using SEM-EDX, XRD, and optical microscopy

This integrated methodology addressed a fundamental challenge in archaeometallurgy: the need to maximize information recovery while minimizing damage to irreplaceable archaeological materials [25].

Key Findings and Interpretation

The CT scanning revealed several previously invisible features within the Tepe Hissar slag:

- Intact copper prills with diameters ranging from 10-500 micrometers, often concentrated in specific regions of the slag mass

- Complex void structures formed by gas evolution during smelting, providing information about viscosity and temperature profiles

- Arsenic-rich phases distributed heterogeneously, suggesting variable behavior of arsenic during smelting and cooling

- Secondary mineralization including calcite, atacamite, and scorodite formed during burial, revealing post-depositional alteration processes [27]

These findings clarified that arsenic existed in different phases across the samples and could migrate within the slag or escape entirely during smelting, complicating interpretations about the deliberate production of arsenical copper [25]. The distribution of copper prills provided new insights into the metal recovery efficiency of early smelting processes, while gas bubble structures shed light on furnace atmospheres and process dynamics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Analytical Resources for Slag Characterization

| Research Reagent/Equipment | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Industrial CT Scanner | Non-destructive 3D internal imaging | Resolution: 5-50 µm, Voltage: 50-200 kV |

| Scanning Electron Microscope | High-magnification imaging and microanalysis | Resolution: 1-10 nm, Accelerating Voltage: 5-30 kV |

| X-Ray Diffractometer | Mineralogical phase identification | Angular Range: 10-80° 2θ, Cu Kα radiation |

| Micro-XRF Spectrometer | Elemental mapping and composition | Spot Size: 20-100 µm, Elements: Na-U |

| Polarized Light Microscope | Petrographic examination of sections | Magnification: 50-1000x, With reflected and transmitted light |

| Reference Mineral Standards | Calibration and quantification | Certified copper minerals and synthetic phases |

Implications for Ancient Metallurgy and Modern Science

Reconstructing Ancient Technological Systems

The application of CT scanning to ancient slag has transformed our understanding of early copper production. By revealing the internal architecture of slag, researchers can now distinguish between different smelting strategies, assess the proficiency of ancient metallurgists, and trace technological evolution with unprecedented resolution [27]. The technique has proven particularly valuable for interpreting the role of arsenic in early metallurgy—an element that could be either a deliberate alloying component or an impurity from specific ore types [25].

The non-invasive nature of CT scanning also ensures the preservation of archaeological materials for future research, allowing contemporary analyses to be validated or revisited as analytical technologies continue to advance. This is particularly important for rare or unique samples from key archaeological contexts.

Methodological Workflow for Comprehensive Analysis

The most effective approach to studying ancient metallurgical materials combines both non-destructive and micro-destructive techniques in a logical sequence that maximizes information recovery while minimizing damage.

Diagram 2: Comprehensive Analytical Workflow for Ancient Slag

Connections to Modern Catalyst Development

The study of ancient metallurgical processes provides valuable historical context for modern materials science, particularly in the field of catalyst development. Ancient smelting represents one of humanity's earliest attempts to control heterogeneous chemical reactions at elevated temperatures—the same fundamental principles that underlie contemporary catalytic processes.

The phase separation between metal, slag, and gas phases in ancient furnaces parallels the interface phenomena critical in supported metal catalysts. Similarly, the management of redox conditions in copper smelting shares conceptual foundations with catalyst activation and regeneration protocols. Understanding how ancient metallurgists manipulated these processes with limited technological resources provides a historical perspective on the evolution of materials engineering.