From Precursor to Performance: Mastering Catalyst Transformation for Advanced Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive examination of catalyst precursor transformation into the active phase, a critical process in developing efficient and sustainable catalysts for pharmaceutical applications.

From Precursor to Performance: Mastering Catalyst Transformation for Advanced Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of catalyst precursor transformation into the active phase, a critical process in developing efficient and sustainable catalysts for pharmaceutical applications. It covers the foundational principles of precursor design and phase evolution, explores innovative synthetic methodologies and real-world biomedical applications, addresses common optimization challenges, and outlines advanced validation and comparative analysis techniques. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current literature and emerging trends to serve as a practical guide for rational catalyst design, aiming to accelerate drug discovery and process optimization.

The Blueprint of Activity: Understanding Precursor Chemistry and Phase Evolution

Defining Catalyst Precursors and the Active Phase in Pharmaceutical Contexts

In the landscape of pharmaceutical manufacturing, the efficient and selective synthesis of complex molecules is paramount. Catalysis stands as a cornerstone technology in this endeavor, enabling routes that are more sustainable, cost-effective, and selective. The journey of a catalyst from an inactive, stable state to a highly reactive one is a critical process, yet it is often overlooked. This transformation, from a catalyst precursor to the active phase, is not merely an academic curiosity but a practical necessity that dictates the success of catalytic cycles in drug development and production [1]. A precursor, in the broadest chemical sense, is a substance from which another substance is derived [2]. Within catalysis, this definition narrows to a compound that contains the essential elements of the future active catalyst but in a stable, often unreactive form. This stability allows for storage, characterization, and controlled activation under specific conditions. The subsequent active phase is the state of the catalyst that actually interacts with reactants, lowering the activation energy of the desired reaction and steering it toward the target pharmaceutical intermediate or product.

Understanding this genesis is crucial for researchers and development professionals. The selection of the precursor, the method of its deposition on a support, and the specific protocol for its activation directly influence critical performance metrics such as activity, selectivity, and lifetime [3] [1]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of catalyst precursors and their transformation, detailing fundamental concepts, characterization methodologies, and the direct implications for pharmaceutical synthesis.

Core Definitions and Conceptual Framework

What is a Catalyst Precursor?

A catalyst precursor is a carefully synthesized and characterized compound that can be transformed into the active catalyst through a defined chemical or thermal process [4] [3]. It is the pre-catalyst state, designed for practicality in handling and preparation before being subjected to conditions that generate the true catalytic sites.

In the context of pharmaceutical production, precursors are often coordination complexes or metal salts that provide a controlled source of the catalytic metal. For instance, chloroplatinic acid (CPA) or platinum tetraammine (PTA) are simple and prevalent precursors used to prepare supported platinum metal catalysts [3]. The term "well-defined catalyst precursors" underscores the importance of precise synthesis and thorough characterization, as knowing the exact structure of the precursor is a prerequisite for understanding and controlling the resulting catalyst's activity and selectivity [4].

What Constitutes the Active Phase?

The active phase is the state of the catalyst material under operational reaction conditions that is responsible for its catalytic function. It is characterized by its ability to facilitate the chemical reaction without itself being consumed. This phase is not always a static, pre-formed entity; it often emerges dynamically as the precursor interacts with the reaction environment (e.g., reactants, temperature, pressure) [5]. A critical concept in modern catalysis is that the solid-state chemistry of the material is strongly coupled with the chemistry of the catalytic reaction. The stability of surface and bulk phases under reaction conditions is determined by the fluctuating chemical potential, meaning the catalyst can undergo restructuring. Thus, the active state is often a "working state" that may be difficult to observe under ambient conditions [5].

The Critical Distinction: Precursors vs. Reagents vs. Catalysts

In chemical synthesis, the terms precursor, reagent, and catalyst hold distinct meanings, and conflating them can lead to confusion in experimental design.

- Precursor: A starting material that is transformed into the active catalyst. It participates in the catalyst's preparation but is not the catalyst itself. Example: Platinum hexachloride,

[PtCl6]^2-, is a precursor that is reduced to form active platinum metal nanoparticles [3]. - Reagent: A substance that is consumed in a chemical reaction to bring about a chemical change in the reactant molecule. Unlike a catalyst, a reagent is not regenerated. Example: A diagnostic reagent used to detect the presence of a specific functional group in a pharmaceutical intermediate [2].

- Catalyst: A substance that increases the rate of a reaction without being consumed. It participates in the reaction cycle but is regenerated at the end. The catalyst exists in its active phase during this process. Example: The reduced platinum metal nanoparticles that catalyze a hydrogenation step in an API synthesis [2].

The relationship between these components is foundational: a precursor is activated to form a catalyst, which then acts upon reagents to transform them into desired products.

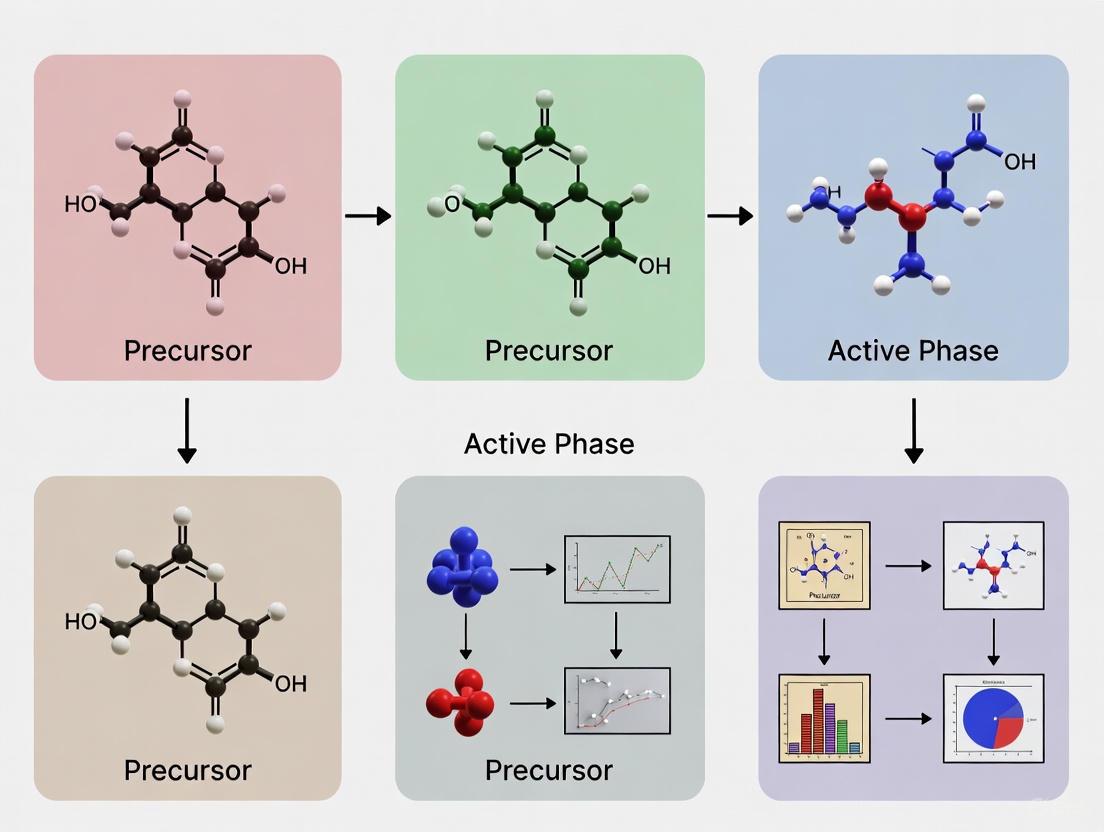

Diagram 1: Conceptual relationship between a catalyst precursor, the active phase, and reagents in a catalytic cycle. The reagent is consumed, while the catalyst is regenerated.

The Transformation Journey: From Precursor to Active Phase

The activation of a catalyst precursor is a complex process involving physical and chemical changes that create the catalytically active sites. This transformation is seldom a single step but a sequence of events dictated by the precursor's nature and the activation environment.

Common Activation Mechanisms

The pathway from precursor to active phase is typically triggered by thermal or chemical treatment. The most common mechanisms include:

- Thermal Decomposition (Calcination): The precursor is heated in an oxidizing or inert atmosphere to decompose the molecular structure, remove volatile components (like ligands or anions), and often form a metal oxide phase. This is a crucial step for creating dispersed oxide species on a support [3].

- Reduction: For metal precursors, this is a fundamental step where the metal ion is reduced to its metallic state (often zero-valent) using a reducing agent like hydrogen gas. The reduction process is sensitive; an "appropriately mild reduction treatment will preserve the high dispersion of the precursor in the reduced metal particles" [3]. The temperature and rate of reduction are critical to avoid sintering, which would decrease the active surface area.

- Oxidation: In some cases, particularly for oxidation catalysts, the precursor may be treated in an oxygen-rich atmosphere to generate the desired metal oxide active phase.

- Dynamic Restructuring under Reaction Conditions: Increasingly, it is recognized that the active phase is not always formed in a pre-treatment step but evolves in situ under the reaction conditions. The material can dynamically restructure in response to the chemical potential of the reacting mixture, meaning the "active state" is a function of the specific catalytic environment [5].

Factors Governing the Transformation

The efficiency of this transformation is governed by several factors intrinsic to the precursor and the support system:

- Dispersion of the Precursor: A foundational principle is that "well dispersed metals are most easily produced from well dispersed metal precursors" [3]. The initial distribution of the precursor on the support material dictates the final dispersion of the active metal. Techniques like Strong Electrostatic Adsorption (SEA) are designed to maximize this initial dispersion by controlling the surface charge of the support and the precursor complex [3].

- Metal-Support Interactions: The support is not inert. It must have an adequate texture—sufficient surface area and appropriately sized pores—to lodge the active phase and allow for the diffusion of reactants and products [1]. The chemical interaction between the precursor/support can stabilize the dispersed metal particles and even create unique active sites at the interface.

- Kinetics of Active State Formation: The "kinetics of the formation of the active states of a catalyst" is a critical and often neglected factor in experimental design. The same catalyst system can follow different activation paths depending on the pre-treatment workflow, leading to different active states and compromising reproducibility [5]. Standardized activation protocols are therefore essential for consistent results.

Diagram 2: The transformation workflow of a catalyst precursor to the active phase, showing key activation pathways.

Experimental Protocols for Preparation and Characterization

Rigorous and standardized experimental procedures are the bedrock of reliable catalyst research. The following protocols outline key methodologies for preparing and characterizing catalyst precursors and their active phases.

Precursor Deposition via Strong Electrostatic Adsorption (SEA)

Objective: To achieve a high and uniform dispersion of a metal precursor on a support material by controlling electrostatic interactions [3].

Methodology:

- Determine the Point of Zero Charge (PZC): The PZC of the support material (e.g., alumina, silica) is first measured. This is the pH at which the surface net charge is zero.

- Prepare Precursor Solution: Dissolve the ionic metal precursor (e.g.,

[PtCl6]^2-for anionic adsorption,[Pt(NH3)4]^2+for cationic adsorption) in deionized water. - Adjust Solution pH: Modify the pH of the precursor solution. For a support with a PZC of 5:

- For anionic precursor adsorption, set the solution pH below the PZC (e.g., pH 3). This protonates surface hydroxyl groups, creating a positive surface charge that attracts anions.

- For cationic precursor adsorption, set the solution pH above the PZC (e.g., pH 10). This deprotonates surface groups, creating a negative surface charge that attracts cations.

- Impregnation: Contact the support with the pH-adjusted precursor solution for a defined period (e.g., 1 hour) with stirring.

- Washing and Drying: Filter the solid, wash it to remove weakly adsorbed ions, and dry it at a moderate temperature (e.g., 110°C).

Characterization: Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) analysis of the solution before and after contact confirms metal uptake. Electron microscopy (TEM/SEM) can later be used to confirm high metal dispersion after reduction [3].

Protocol for a "Clean" Catalyst Test and Kinetic Analysis

Objective: To generate consistent, high-quality functional data on catalyst performance while accounting for the catalyst's dynamic nature, thereby producing data suitable for AI and machine learning analysis [5].

Methodology:

- Rapid Activation: Expose the fresh catalyst precursor to harsh reaction conditions (e.g., high temperature, up to 450°C) for 48 hours to quickly drive it into a steady-state. This step identifies rapidly deactivating materials.

- Systematic Kinetic Testing:

- Step 1: Temperature Variation: Measure conversion and selectivity at different temperatures while holding other parameters constant.

- Step 2: Contact Time Variation: Measure performance at different gas flow rates (or catalyst weights) to understand the effect of residence time.

- Step 3: Feed Variation: Systematically alter the feed composition:

- (a) Co-dose a reaction intermediate.

- (b) Vary the reactant/oxygen ratios.

- (c) Change the water vapor concentration.

- Post-Reaction Characterization: Analyze the spent catalyst using techniques like XPS and Nâ‚‚ adsorption to link changes in physicochemical properties to performance data [5].

This "clean experiment" protocol, documented in an "experimental handbook," ensures that the kinetics of active state formation are consistently considered, mitigating reproducibility issues [5].

Essential Characterization Techniques

A multi-technique approach is vital for correlating precursor properties with the resulting active phase's performance. Key techniques are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Characterization Techniques for Catalyst Precursors and Active Phases

| Technique | Analytical Information | Application to Precursors | Application to Active Phase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nâ‚‚ Physisorption | Specific surface area, pore volume, pore size distribution | Textural properties of the support material [1] | Monitor textural changes (e.g., pore blocking, sintering) after reaction [1] |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Elemental composition, chemical state, oxidation state | Confirm identity of deposited precursor species | Determine oxidation state of the active metal in situ under reaction conditions [5] |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) | Elemental composition, metal loading | Quantify metal uptake after impregnation [3] | Check for metal leaching after catalytic use |

| Electron Microscopy (TEM/SEM) | Particle size, morphology, dispersion | Study the distribution of the precursor on the support | Directly image the size and shape of active metal nanoparticles [3] |

| In Situ/Operando Characterization | Structure and properties under reaction conditions | - | Identify the true active phase and dynamic restructuring processes [5] [1] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental study of catalyst precursors requires a suite of specialized reagents, supports, and analytical tools. The following table details key materials and their functions in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Catalyst Precursor Studies

| Item | Function in Research | Example in Pharmaceutical Context |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Salt Precursors | Source of the catalytic metal; choice dictates dispersion and ease of reduction. | Chloroplatinic Acid, Ammonium Metavanadate, Nickel Nitrate [3] [5] |

| High Surface Area Supports | Provide a scaffold to disperse the active phase, prevent sintering, and enable diffusion. | Alumina, Silica, Titania, Carbon [1] |

| Gases for Activation & Reaction | Used for precursor reduction, oxidation, and as reactants in catalytic tests. | Hydrogen (Hâ‚‚) for reduction, Oxygen (Oâ‚‚) for oxidation, Inert gases (Nâ‚‚, Ar) [5] [1] |

| Reference Catalysts | Benchmarks for comparing the activity and selectivity of newly synthesized catalysts. | Commercially available Pt/Al₂O₃, Ni/SiO₂ catalysts |

| Analytical Standards | Calibrate instruments for accurate quantification of reaction products and metal loadings. | ICP standards, GC/MS calibration mixes for pharmaceutical intermediates [3] |

| Propargyl-PEG3-triethoxysilane | Propargyl-PEG3-triethoxysilane|Click Chemistry Reagent | |

| Thalidomide-piperazine-Boc | Thalidomide-piperazine-Boc, MF:C22H26N4O6, MW:442.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implications for Pharmaceutical Precursors Production

The principles of catalyst precursor activation have direct and profound implications for the synthesis of pharmaceutical precursors—the intermediate compounds that are the essential building blocks for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) [6].

- Efficiency and Sustainability: Optimized catalysts, derived from well-designed precursors, directly impact the efficiency and sustainability of pharmaceutical precursor production. For example, metabolic engineering of microorganisms to produce pharmaceutical precursors can be enhanced by catalytic steps that reduce costs and environmental impact [6].

- Role of Biocatalysis: In pharmaceutical contexts, biocatalysis—using enzymes or whole cells as catalysts—is a prominent technology. Here, the "precursor" might be an proenzyme or a vitamin-derived cofactor that is activated within a biological pathway. Biocatalysis offers high selectivity under mild reaction conditions, improving product purity and aligning with green chemistry principles [6].

- Regulatory and Quality Compliance: The production of both catalyst precursors and pharmaceutical intermediates is subject to strict regulatory oversight. "Regulatory considerations play a critical role in pharmaceutical precursor production, requiring strict adherence to quality standards to ensure that intermediates are safe for further processing into drugs" [6]. This necessitates rigorous characterization and controlled activation protocols for catalysts used in these syntheses.

The journey from a defined catalyst precursor to a functional active phase is a sophisticated process at the heart of modern catalytic chemistry, especially in the demanding field of pharmaceutical synthesis. A deep understanding of the definitions, transformation mechanisms, and standardized experimental protocols is not merely academic but a practical requirement for innovation. Controlling this genesis allows researchers and drug development professionals to design catalysts with superior activity, selectivity, and stability. As the field moves towards more data-centric approaches, the generation of "clean," consistent data through rigorous protocols will be the foundation for unlocking new AI-driven discoveries [5]. This, in turn, will accelerate the development of more efficient and sustainable routes to the complex molecules that define the future of medicine.

The journey from a synthetic catalyst material to a functional active phase is governed by the nature of its precursor. In heterogeneous catalysis, catalyst precursors are the initial, often inactive, forms of a catalyst that undergo chemical and physical transformations under specific conditions to generate the active phase responsible for catalytic activity [7]. Understanding these precursor classes—spanning simple salts and coordination complexes to structured solids—is fundamental to the rational design of high-performance catalysts. The transformation pathway, dictated by the precursor's chemical composition, structure, and stability, ultimately determines critical properties of the final catalyst, including active site density, dispersion, stability, and longevity [7]. This guide provides a comprehensive technical examination of major catalyst precursor classes, their transformation pathways to active phases, and the experimental methodologies essential for their characterization within broader catalyst precursor transformation research.

Fundamental Precursor Classes and Their Characteristics

Catalyst precursors can be systematically categorized based on their chemical nature and structure. The table below summarizes the key classes, their typical compositions, and the active phases they form.

Table 1: Key Catalyst Precursor Classes and Their Transformation Outcomes

| Precursor Class | Typical Composition Examples | Transformation Conditions | Resulting Active Phase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Salts | Nitrates (e.g., Fe(NO₃)₃), Chlorides, Ammonium Salts | Calcination, Reduction (in H₂ or CO) [7] | Metal Oxides, Reduced Metals (e.g., FeⰠfrom hematite) [7] |

| Coordination Complexes | Metal carbonyls, Ammines, Acetylacetonates | Thermal Decomposition, Oxidation | Dispersed Metal Nanoparticles, Metal Oxides |

| Structured Solids | Zeolites, Mixed Metal Oxides, Perovskites | Ion Exchange, Activation | Brønsted Acid Sites, Multifunctional Active Sites |

| Precipitated Hydroxides & Oxyhydroxides | FeOOH, Co(OH)â‚‚, Ni(OH)â‚‚ | Dehydration, Phase Transformation | Metal Oxides, Spinel Structures [8] |

The selection of a precursor class is critical, as it influences not only the final active phase but also the catalyst's deactivation behavior. For instance, catalyst deactivation through pathways like coking (carbon deposition), poisoning, and thermal degradation remains a fundamental challenge, and precursor design is a primary strategy for mitigating these issues [9].

Experimental Protocols for Precursor Synthesis and Characterization

Tracking the transformation of a precursor to its active phase requires a suite of advanced characterization techniques. The following workflow outlines a standard experimental approach, from synthesis to activity evaluation.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for studying catalyst precursor transformation.

Key Characterization Techniques

The following table details the core characterization techniques used to probe precursor transformation, along with their specific functions and applications as demonstrated in the search results.

Table 2: Essential Characterization Techniques for Precursor Analysis

| Technique | Acronym | Primary Function | Key Information Obtained | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-Ray Powder Diffraction [10] | XRPD / XRD | Phase identification and structure refinement. | Crystal structure, phase composition, crystallite size. | Identifying the transformation of hematite (Fe₂O₃) to active iron carbides (e.g., χ-Fe₅C₂) in Fe-based Fischer-Tropsch catalysts [7]. |

| Rietveld Analysis [10] | - | Quantitative phase analysis from XRD data. | Weight fractions of crystalline phases, unit cell parameters. | Refining the structure of microporous materials like zeolites and quantifying phase changes in mixed metal oxides [10]. |

| X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy | XAS (EXAFS/XANES) | Probing local atomic environment. | Oxidation state, coordination number, bond distances. | Used in operando studies to identify the atomic and electronic structure of active sites during the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) [7]. |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy [8] | SEM | Imaging morphology and particle size. | Particle morphology, size distribution, surface texture. | Observing the micro-spherical morphology and attrition strength of spray-dried Fe Fischer-Tropsch catalysts before and after reaction [8]. |

| Energy Dispersive X-Ray Analysis [11] | EDX | Elemental composition analysis. | Local chemical composition and element distribution. | Determining the chemical composition of catalyst-coated membranes and synthesized electrocatalysts [11]. |

Detailed Methodological Protocol

Based on the search results, a robust protocol for studying precursor transformation, particularly for a system like iron Fischer-Tropsch catalysts, involves the following steps:

- Precursor Synthesis and Shaping: Precipitate an iron catalyst precursor with a nominal composition of 100 Fe/3 Cu/5 K/16 SiO₂ (by weight). The silica acts as a structural promoter. The precursor can be shaped via spray-drying to form micro-spherical particles (5-40 μm) ideal for slurry reactor studies [8].

- Initial Characterization:

- Activation and In-Situ Characterization:

- Activate the precursor in a controlled atmosphere, typically Hâ‚‚, CO, or syngas (a mixture of Hâ‚‚ and CO) [7].

- Employ in-situ XAS to monitor the reduction of Fe³⺠and the subsequent formation of iron carbides in real-time, tracking changes in oxidation state and local coordination [7].

- Use in-situ XRD to identify the crystalline phases that appear and disappear during activation (e.g., the transition from Fe₃O₄ to χ-Fe₅C₂) [7] [10].

- Post-Reaction Analysis:

- Performance Correlation:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are fundamental for research in catalyst precursor transformation.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Precursor Transformation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Technical Note |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Salts (Nitrates, Chlorides) | Common starting precursors for impregnation and precipitation synthesis. | High purity is critical to avoid unintended poisoning; nitrates are often preferred over chlorides to avoid residual chlorine [9]. |

| Structural Promoters (e.g., Colloidal Silica) | Enhances mechanical strength and attrition resistance of catalyst particles [8]. | The type of silica (colloidal, silicate) significantly impacts the final catalyst's durability in slurry reactors [8]. |

| Reducing Gases (Hâ‚‚, CO, Syngas) | Activating precursors to their metallic or carbidic active phases [7]. | The choice of reductant (Hâ‚‚ vs. CO/syngas) dictates the active phase formed (Feâ° vs. FexCy) in iron-based catalysts [7]. |

| Calibration Standards (for XAS) | Essential for accurate energy calibration during synchrotron-based measurements. | Foil standards (e.g., Fe, Co) are used to align the energy scale of the monochromator. |

| Specialized Gaskets & Windows (for In-Situ Cells) | Enable the containment of samples under controlled environments (high T, P, reactive gases) during characterization. | Made from X-ray transparent materials (e.g., boron nitride, diamond) for in-situ XRD and XAS. |

| MC-Gly-Gly-Phe-Gly-NH-CH2-O-CH2COOH | MC-Gly-Gly-Phe-Gly-NH-CH2-O-CH2COOH, MF:C28H36N6O10, MW:616.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Rhodamine-N3 chloride | Rhodamine-N3 chloride, MF:C44H59ClN8O7, MW:847.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The systematic classification and detailed understanding of catalyst precursor classes—from simple salts to structured solids—provide the foundational knowledge required for advanced catalyst design. The transformation pathway from precursor to active phase is not merely a procedural step but a critical determinant of the catalyst's ultimate identity, functionality, and operational lifetime. By employing an integrated methodology that combines synthesis, advanced in-situ characterization, and performance evaluation, researchers can move beyond correlative observations to establish causal relationships in catalyst genesis. This rigorous approach is indispensable for tackling persistent challenges in catalysis, such as deactivation, and for pioneering the next generation of high-performance, durable catalytic materials.

The Thermodynamic and Kinetic Drivers of Phase Transformation

The transformation of a catalyst from its precursor phase to its active state is a complex process governed by fundamental thermodynamic and kinetic principles. In catalysis research, controlling this phase evolution is paramount to achieving high activity, selectivity, and stability. Metastable phases—structures with higher free energy than their thermodynamically stable counterparts but persisting due to kinetic constraints—often exhibit exceptional catalytic properties distinct from their stable forms [12]. This technical guide examines the drivers of phase transformation within the specific context of catalyst precursor activation, providing researchers with the theoretical frameworks and experimental methodologies needed to precisely control these processes for advanced catalytic applications across thermal, electro-, and photocatalytic systems.

Theoretical Foundations

Thermodynamic Driving Forces

Thermodynamics dictates the direction and equilibrium states of phase transformations through the minimization of Gibbs free energy. For any material, the phase with the lowest Gibbs free energy (G) under specific temperature, pressure, and compositional conditions is thermodynamically stable. Metastable phases possess higher free energy states but remain accessible through kinetic control of synthesis parameters [12].

The thermodynamic competition between phases can be quantified for a target phase k as [13]: ΔΦ(Y) = Φk(Y) - min[i∈Ic] Φi(Y) where Φi(Y) represents the free energy of phase i under intensive variables Y (e.g., pH, redox potential, concentration). The condition where thermodynamic competition is minimized occurs when this difference is maximized, favoring the nucleation and growth of the target phase over competing by-products [13].

In aqueous synthesis systems, the Pourbaix potential (Ψ) provides the free-energy surfaces needed to compute thermodynamic competition [13]: Ψ = (1/NM)[(G - NOμH₂O) - RT×ln(10)×(2NO-NH)pH - (2NO-NH+Q)E] where NM, NO, NH represent metal, oxygen, and hydrogen atom counts, Q is phase charge, R is the ideal gas constant, T is temperature, and E is redox potential.

Kinetic Barriers and Pathways

While thermodynamics determines the equilibrium state, kinetics governs the rate and pathway of phase transformation through energy barriers that must be overcome for nucleation and growth to proceed. The magnitude of the thermodynamic driving force serves as an effective proxy for phase transformation kinetics, appearing directly in the kinetic equations of nucleation, diffusion, and growth [13].

The Phase Transformation Graph theoretical framework reveals that the interconnectivity of multiple structural states through transformation pathways significantly impacts transformation reversibility and defect generation [14]. Martensitic transformations in shape memory alloys demonstrate that symmetry breaking during phase changes generates specific topological defects—dislocations and grain boundaries—that influence functional properties and cycling stability [14].

Table 1: Fundamental Parameters Governing Phase Transformation

| Parameter | Thermodynamic Role | Kinetic Influence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG) | Determines phase stability and driving force for transformation | Correlates with nucleation and growth rates; larger | ΔG | typically accelerates kinetics |

| Temperature | Affects relative phase stability through TΔS term | Governs atomic diffusion rates and thermal energy to overcome activation barriers | ||

| Composition | Determines stable phase fields in equilibrium diagrams | Influences diffusion paths and intermediate phase formation | ||

| Interface Energy | Contributes to total system energy, especially in nanoscale systems | Creates barriers to nucleation; critical nucleus size depends on interfacial terms | ||

| Symmetry Relationship | Group-subgroup relationships enable reversible transformations [14] | Determines number of transformation pathways and variant structures [14] |

Synthesis Methodologies for Controlled Phase Transformation

Thermodynamic Optimization via Minimum Thermodynamic Competition

The Minimum Thermodynamic Competition framework provides a systematic approach to identify synthesis conditions that maximize the free energy difference between target and competing phases [13]. This strategy minimizes the kinetic formation of undesired by-products even within the thermodynamic stability region of the target phase.

Experimental Protocol: MTC-Guided Synthesis Optimization

- Construct comprehensive phase diagrams using computational thermodynamics for the system of interest

- Calculate Pourbaix potentials for all competing phases using first-principles data [13]

- Identify optimal synthesis conditions where ΔΦ(Y) is maximized using gradient-based optimization algorithms [13]

- Validate experimentally by synthesizing across a range of conditions and characterizing phase purity

Application of this protocol to LiIn(IO₃)₄ and LiFePO₄ demonstrated that phase-pure synthesis occurs only when thermodynamic competition with undesired phases is minimized, not merely within the stability region of the thermodynamic Pourbaix diagram [13].

Metastable Phase Stabilization Strategies

Metastable phase materials can be stabilized through various synthesis techniques that leverage kinetic control over thermodynamic preferences [12]:

- Low-Temperature Aqueous Routes: Utilizing solution conditions that maximize driving force to target phase while minimizing competing pathways [13]

- Mechanochemical Synthesis: Applying mechanical energy to overcome nucleation barriers for metastable phases [12]

- Template-Directed Crystallization: Using surfaces or molecular templates to preferentially nucleate metastable structures

- Rapid Thermal Processing: Employing short-time, high-temperature treatments to form metastable intermediates before they convert to stable phases

Table 2: Metastable Phase Synthesis Techniques and Applications

| Synthesis Method | Key Controlling Parameters | Catalytic Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrothermal/Solvothermal | Temperature, pH, precursor concentration, filling degree | Metastable β-Fe₂O3 photoanodes [12], 2M-WS₂ topological superconductors [12] | Limited to stable precursors at reaction conditions |

| Electrochemical Deposition | Potential, electrolyte composition and concentration, pH | 3R-iridium oxide for oxygen evolution [12], Mo-doped Co₃O₄ [15] | Substrate-dependent, limited thickness control |

| Strong Electrostatic Adsorption | Solution pH relative to support PZC, precursor complex charge [3] | Highly dispersed Pt, Pd, Cu catalysts [3] | Requires precise pH control, limited to suitable precursors |

| Flame Spray Pyrolysis | Precursor concentration, flame temperature, quenching rate | High-temperature metastable oxides [12] | Requires specialized equipment, limited structural control |

Computational and High-Throughput Approaches

AI-Guided Discovery of Metastable Phases

Artificial intelligence approaches are revolutionizing the discovery of novel metastable phase materials by overcoming limitations of conventional thermodynamic phase diagrams [12]. Machine learning algorithms can predict synthesis conditions for metastable phases by learning from both successful and failed experiments, enabling inverse design of catalysts with tailored thermodynamic-kinetic profiles [12].

High-Throughput Screening of Bimetallic Catalysts

A proven high-throughput protocol for bimetallic catalyst discovery utilizes the similarity in electronic density of states patterns as a screening descriptor [16]. This approach successfully identified Pd-free Ni61Pt39 as a high-performance catalyst for Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ synthesis with 9.5-fold enhancement in cost-normalized productivity compared to conventional Pd catalysts [16].

Experimental Protocol: DOS Similarity Screening

- Calculate formation energies for 4350 candidate bimetallic structures using DFT [16]

- Filter thermodynamically feasible alloys (ΔEf < 0.1 eV) [16]

- Compute DOS similarity to reference catalyst using [16]: ΔDOSâ‚‚â‚‹â‚ = {∫[DOSâ‚‚(E) - DOSâ‚(E)]² g(E;σ)dE}¹áŸÂ² where g(E;σ) = (1/σ√2Ï€)e^(-(E-Ef)²/2σ²)

- Select top candidates with lowest ΔDOS values for experimental validation

This protocol demonstrates that including both d-states and sp-states in DOS comparisons is essential, as sp-band interactions often dominate adsorbate binding in catalytic reactions [16].

Characterization Techniques for Phase Analysis

In Situ and Operando Methods

Modern characterization techniques enable direct observation of phase transformations under realistic synthesis and reaction conditions:

- In Situ XRD: Tracks crystal structure evolution in real-time during thermal treatment or under reaction atmospheres

- Environmental TEM: Directly visualizes phase transformations at atomic resolution with gas or liquid environments

- XAS/EXAFS: Probes local coordination and electronic structure changes during transformation [15]

- AP-XPS: Monitors surface composition and oxidation states during catalytic reactions

Phase Quantification Methods

Accurate quantification of phase fractions is essential for correlating transformation extent with catalytic properties. Rietveld refinement of XRD patterns provides precise phase quantification, while electron backscatter diffraction statistically maps phase distributions at microstructural levels [17].

Applications in Catalytic Systems

Electrocatalyst Phase Transformations

In electrocatalysis, phase transformations can be intentionally induced to create highly active structures. Examples include:

- Local structural phase transition in cobalt fluoride-sulfide (CoFS) optimized electronic structure for oxygen evolution reaction, requiring only 270 mV overpotential at 10 mA cmâ»Â² [15]

- Phase transition from 2H to 1T MoSeâ‚‚ through doping created expanded interlayer spacing and enhanced metallic properties, improving hydrogen evolution activity by reducing overpotential by 168 mV at 10 mA cmâ»Â² [15]

- Gd₃Feâ‚…Oâ‚â‚‚ transformation from garnet oxide to peroxide and iron dramatically enhanced COâ‚‚ reduction selectivity to nearly 100% Faradaic efficiency for CO [15]

Thermal Catalyst Activation

The transformation of catalyst precursors to active phases under thermal treatment follows specific pathways influenced by support interactions, precursor dispersion, and atmosphere [3]. Strong Electrostatic Adsorption enables precise control over precursor dispersion, which preserves high metal dispersion during reduction to active metallic phases [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Phase Transformation Studies in Catalysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Chloroplatinic Acid (CPA) | Source of [PtCl₆]²⻠for strong electrostatic adsorption [3] | Preparation of highly dispersed Pt catalysts on oxide supports |

| Platinum Tetraammine (PTA) | Source of [(NH₃)₄Pt]²⺠for opposite-charge SEA [3] | Catalyst preparation on supports with high PZC |

| Transition Metal Ammines | Cationic precursors for electrostatic adsorption [3] | Cu, Pd, Ni catalyst preparation on low PZC supports |

| Oxide Supports with Controlled PZC | Enable selective precursor adsorption via pH control [3] | Al₂O₃ (PZC ~8), SiO₂ (PZC ~4) for selective deposition |

| Aqueous Buffers | Precise pH control during impregnation [3] | Optimization of electrostatic adsorption conditions |

Visualization of Phase Transformation Concepts

Thermodynamic Competition in Phase Selection

Phase Transformation Pathways Network

Catalyst Synthesis Workflow

Understanding the transformation of catalyst precursors into their active phases is a fundamental aspect of heterogeneous catalysis research. This structural evolution directly governs the formation of active sites, ultimately determining catalytic activity, selectivity, and stability. Characterization of these solid-state transformations requires techniques that probe bulk and local structure, composition, and reducibility. Among the most critical techniques for this purpose are X-ray Diffraction (XRD), X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS), and Temperature-Programmed Reduction (TPR). This technical guide details the application of these techniques within the specific context of tracking catalyst precursor transformations, providing researchers with methodologies, data interpretation frameworks, and practical protocols.

X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) for Phase Identification and Structure

Theoretical Foundations and Application

X-ray Diffraction is a primary technique for bulk phase identification and structure determination in solid catalysts. The principle is based on Bragg's Law (nλ = 2d sinθ), where constructive interference of X-rays occurs when they are scattered by the periodic atomic planes in a crystalline material [18]. The angular positions (2θ) of the resultant diffraction peaks provide information on the unit cell dimensions and symmetry, while the peak intensities relate to the atomic arrangement within the unit cell, and peak broadening can indicate crystallite size and microstrain [10] [18].

For catalyst precursor transformation studies, XRD is indispensable for monitoring phase changes during calcination and activation treatments. It can identify the crystalline phases present in the precursor, detect intermediate phases formed during thermal processing, and confirm the formation of the desired final active phase [10]. This is crucial for establishing the correct thermal treatment protocols to ensure complete precursor decomposition and transformation without forming undesired, inactive phases.

Experimental Protocol for Phase Transformation Studies

Sample Preparation:

- For powder samples, ensure a flat, uniform surface to minimize preferred orientation.

- For in-situ studies, use a high-temperature stage or capillary reactor to simulate process conditions.

Data Collection Parameters:

- Use Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å) as the X-ray source.

- Set voltage and current to 45 kV and 40 mA, respectively [19].

- Perform 2θ scans from 5° to 90° at a scan speed of 0.02° to 0.05° per second [19].

- For in-situ experiments, collect patterns at set temperature intervals (e.g., every 50°C or 100°C) during heating under controlled atmosphere.

Data Analysis:

- Phase Identification: Compare collected patterns with reference databases (e.g., ICDD PDF) to identify crystalline phases.

- Quantitative Analysis: Use Rietveld refinement to quantify phase abundance, lattice parameters, and crystallite size [10].

- Crystallite Size Determination: Apply the Scherrer equation (D = Kλ / β cosθ) to estimate volume-weighted crystallite size from peak broadening, where K is the shape factor, λ is the X-ray wavelength, β is the integral breadth of the peak, and θ is the Bragg angle.

Table 1: Key XRD Parameters for Catalyst Characterization

| Parameter | Typical Value/Range | Information Obtained |

|---|---|---|

| Radiation Source | Cu Kα (λ = 1.54 Å) | Optimal balance of penetration and resolution |

| Scan Range (2θ) | 5° - 90° | Captures major diffraction lines for most materials |

| Scan Speed | 0.02° - 0.05°/s | Balance between data quality and collection time |

| Crystallite Size Range | 1 - 100 nm | Accessible via Scherrer equation analysis |

Advanced XRD Applications

The Rietveld method is a powerful tool for structure refinement of polycrystalline catalysts, allowing for the precise determination of atomic coordinates, site occupancies, and thermal parameters, even for complex mixed-phase systems [10]. Furthermore, in-situ XRD is increasingly used to track dynamic structural changes in real-time under reaction conditions, providing direct insight into the phase transitions that define the catalyst's activation pathway [20].

X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS) for Local Structure and Electronic State

Principles and Relevance to Precursor Transformation

While XRD provides long-range order, X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy probes the local electronic structure and coordination environment of a specific element, regardless of its crystallinity. This makes it exceptionally powerful for studying catalyst precursors and supported metal catalysts, where the active phase may be amorphous or highly dispersed [21] [22]. XAS is divided into two regions:

- XANES (X-ray Absorption Near Edge Structure): Provides information on the oxidation state and geometry of the absorbing atom.

- EXAFS (Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure): Provides quantitative data on interatomic distances, coordination numbers, and disorder in the local environment [19].

This technique is ideal for tracking the evolution of the local coordination and oxidation state of metal atoms during precursor decomposition, which often occurs before long-range crystalline order is established.

Experimental Protocol for In-Situ XAS

Sample Preparation:

- For transmission mode, homogenously mix and press the powdered catalyst with boron nitride to achieve an optimal absorption edge step (Δμx ≈ 1.0).

- For fluorescence mode (dilute samples), use a thin layer of powder on adhesive tape.

In-Situ Cell Setup:

- Use an electrochemical or flow reactor cell with X-ray transparent windows (e.g., Kapton) [19].

- For thermal transformations, incorporate heating and gas delivery systems to control the atmosphere (e.g., Hâ‚‚, He, Oâ‚‚).

Data Collection:

- Align the sample and position detectors (ion chambers for transmission, fluorescence detector for dilute samples).

- Collect spectra at the absorption edge of the element of interest (e.g., Mn K-edge at 6539 eV) [19].

- For in-situ studies, acquire spectra at a sequence of applied potentials or temperatures to track dynamic changes.

Data Analysis:

- XANES: Determine the average oxidation state by comparing the edge position of the sample with those of reference compounds with known oxidation states.

- EXAFS: Fourier transform the oscillatory data to obtain a radial distribution function. Fit the data to theoretical models to extract coordination numbers (CN), interatomic distances (R), and disorder factors (Debye-Waller factor, σ²).

Table 2: Key XAS Parameters for Catalyst Characterization

| Parameter | Information Obtained | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Edge Position (XANES) | Average oxidation state | Tracking Mn oxidation from Mn(II,III) to Mn(III,IV) during OER [19] |

| Pre-edge Features | Site symmetry, geometry | Distinguishing tetrahedral vs. octahedral coordination |

| Coordination Number (EXAFS) | Number of nearest neighbors | Determining metal dispersion or cluster formation |

| Interatomic Distance (EXAFS) | Bond lengths | Detecting metal-support interactions |

Case Study: Manganese Oxide Catalyst

In-situ XAS was used to study a bifunctional manganese oxide catalyst. Under an oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) potential (0.7 V vs. RHE), XANES and EXAFS revealed a disordered Mn₃O₄ phase. When the potential was switched to an oxygen evolution reaction (OER) condition (1.8 V vs. RHE), approximately 80% of the catalyst was oxidized to a mixed Mn(III,IV) oxide phase, identifying it as the active phase for OER [19]. This demonstrates the power of in-situ XAS in linking specific structural motifs to catalytic function.

Temperature-Programmed Reduction (TPR)

Fundamentals and Methodology

Temperature-Programmed Reduction is a vital technique for characterizing the reducibility of catalyst precursors and the interaction between active metal phases and their supports. In a TPR experiment, the catalyst sample is heated in a linear fashion under a flowing stream of reducing gas (typically Hâ‚‚ in an inert carrier). The consumption of hydrogen is monitored as a function of temperature, producing a TPR profile with characteristic reduction peaks. The temperature of these peaks indicates the reduction temperature of different species, while the area under the curve is proportional to the total amount of hydrogen consumed, which can be used to quantify the reducible species present.

Experimental Protocol

Apparatus Setup:

- Use a U-shaped quartz reactor placed inside a temperature-controlled furnace.

- Employ a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) to measure hydrogen consumption.

- Include a cold trap (e.g., isopropanol/liquid Nâ‚‚) before the TCD to remove water produced during reduction.

Standard Procedure:

- Pretreatment: Load 50-100 mg of catalyst precursor. Pre-treat in an inert flow (He/Ar) at 150-300°C to remove moisture and adsorbed contaminants.

- Baseline Stabilization: Switch to the reducing gas mixture (e.g., 5% H₂/Ar) and allow the baseline to stabilize at low temperature (e.g., 50°C).

- Temperature Ramp: Initiate a linear temperature ramp (typically 5-10°C/min) from 50°C to a final temperature (e.g., 800-900°C, depending on the material).

- Calibration: Quantify hydrogen consumption by calibrating with a known amount of a standard material, such pure CuO.

Data Interpretation:

- Peak Temperature (Tₘâ‚â‚“): Indicates the reducibility of a phase; a lower Tₘâ‚â‚“ suggests easier reduction.

- Peak Area: Quantifies the total amount of reducible species.

- Peak Shape and Number: Provides insight into the presence of multiple reducible species, their homogeneity, and the strength of metal-support interactions. Broad or multiple peaks can indicate a distribution of particle sizes or strong interactions.

Table 3: Key TPR Parameters for Catalyst Characterization

| Parameter | Typical Value/Range | Impact on Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Mass | 50 - 100 mg | Prevents signal saturation and mass/heat transfer limitations |

| Gas Composition | 5 - 10% Hâ‚‚ in Ar | Standard reducing atmosphere, safe concentration |

| Heating Rate (β) | 5 - 10 °C/min | Balance between resolution and sensitivity |

| Flow Rate | 20 - 40 mL/min | Ensures efficient gas-solid contact and product removal |

Integrated Workflow and Technique Comparison

The true power of these techniques is realized when they are used in combination, providing a multi-scale view of the catalyst transformation process. A typical integrated workflow begins with TPR to identify the optimal temperature window for reducing the precursor. This is followed by in-situ XRD to monitor the crystalline phase evolution during this thermal treatment. Finally, XAS is applied to characterize the local structure and oxidation state of the reduced active phase, which may lack long-range order.

Figure 1: Integrated Workflow for Characterizing Catalyst Transformation.

Table 4: Comparative Overview of XRD, XAS, and TPR Techniques

| Characteristic | XRD | XAS | TPR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Information | Bulk crystal structure, phase ID, crystallite size | Local structure, oxidation state, coordination | Reducibility, metal-support interaction |

| Crystallinity Requirement | Crystalline (Long-range order) | Crystalline or Amorphous | N/A |

| Element Specificity | No (Probes all crystalline phases) | Yes (Element-specific) | Indirectly (via consumption of Hâ‚‚) |

| In-Suit/Operando Capability | Excellent [20] | Excellent [19] | Standard (the technique itself is in-situ) |

| Key Limitation | Insensitive to amorphous phases & surface species | Requires synchrotron for best quality | Does not provide structural details |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Characterization Experiments

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Boron Nitride (BN) | Chemically inert diluent and binder | Preparing homogeneous, self-supporting pellets for XRD and transmission XAS [19] |

| Reference Compounds | Standards for calibration and quantification | CuO for TPR calibration; MnO, Mn₂O₃, MnO₂ for XANES oxidation state analysis [19] |

| High-Purity Gases | Creating controlled atmospheres | 5% Hâ‚‚/Ar for TPR; Oâ‚‚, He for pretreatment; specific gas mixtures for in-situ studies |

| X-Ray Transparent Windows | Enabling in-situ analysis | Kapton or silicon nitride windows for in-situ XAS and XRD cells [19] |

| ICDD PDF Database | Reference for phase identification | Comparing acquired XRD patterns to known crystal structures for phase assignment [18] |

| 3-Iodo-L-thyronine-13C6 | 3-Iodo-L-thyronine-13C6 Stable Isotope | 3-Iodo-L-thyronine-13C6 is a C13-labeled internal standard for precise LC-MS/MS quantification of thyroid hormone metabolites in research. For Research Use Only. |

| Thalidomide-5-NH2-CH2-COOH | Thalidomide-5-NH2-CH2-COOH, MF:C15H13N3O6, MW:331.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The transformation of a catalyst precursor into its active state is a complex process involving changes in structure, composition, and oxidation state. A single characterization technique provides only a partial view. XRD delivers critical information on long-range order and phase identity, XAS offers unparalleled insight into the local coordination and electronic state of elements, and TPR quantifies reducibility and metal-support interactions. By integrating these techniques, particularly in in-situ or operando modes, researchers can construct a comprehensive, dynamic picture of the catalyst activation pathway. This multi-faceted understanding is the cornerstone of rational catalyst design and optimization, enabling the development of more efficient and sustainable catalytic processes.

The pursuit of efficient and stable heterogeneous catalysts is a central theme in chemical engineering, particularly for sustainable energy applications such as dimethyl ether (DME) synthesis and COâ‚‚ hydrogenation to methanol. The Cu-Zn-Al (CZA) catalyst system, a cornerstone of industrial methanol production, derives its ultimate catalytic performance not merely from its bulk composition but from the structural evolution of its precursor phases during synthesis and activation. The journey from a mixed hydroxide carbonate precursor to the active metallic catalyst involves complex phase transformations that critically define the catalyst's active site distribution, stability, and overall activity [23] [24]. This case study, situated within a broader thesis on catalyst precursor transformation, provides an in-depth examination of the deliberate phase transition from a hydrotalcite (HTl) to a zincian malachite (ZM)-rich structure in CZA catalysts. We explore how this transition, governed by synthesis parameters, directly dictates the final catalyst's physicochemical properties and its performance in the single-step synthesis of DME from syngas. Understanding and controlling this precursor chemistry is paramount for the rational design of next-generation catalysts with enhanced activity and longevity.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Catalyst Synthesis via Coprecipitation

The foundation of a high-performance CZA catalyst is a well-controlled coprecipitation process, which determines the nature of the precursor phase.

- Solution Preparation: Two aqueous solutions are prepared. Solution A contains metal nitrates—copper nitrate trihydrate (Cu(NO₃)₂·3H₂O), zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O), and aluminum nitrate nonahydrate (Al(NO₃)₃·9H₂O)—dissolved in deionized water in the desired molar ratios. Solution B is an alkaline precipitating solution, typically a mixture of sodium carbonate (Na₂CO₃) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH) [23].

- Precipitation Procedure: Both solutions are added dropwise, simultaneously, into a reactor containing a known volume of deionized water under vigorous stirring. The pH of the precipitation is a critical parameter and is maintained constant (±0.2 pH units) throughout the process by adjusting the relative addition rates of the two solutions [25].

- Aging and Washing: The resulting slurry is aged at a constant temperature (e.g., 338 K for 1 hour) to facilitate the crystallization of the precursor phases. The precipitate is then filtered and thoroughly washed with deionized water until the effluent is free of alkali metal ions (e.g., Naâº) [23].

- Drying and Calcination: The filter cake is dried overnight at 378 K to remove physisorbed water. The dried precursor is subsequently calcined in a static or flowing air atmosphere (typically at 573 K to 673 K for 4-6 hours) to decompose the hydroxycarbonates and form the corresponding mixed metal oxides (CuO, ZnO, Al₂O₃) [23] [25].

Hybrid Catalyst Formulation via Kneading Extrusion

For applications like direct DME synthesis, a bifunctional hybrid catalyst is required. A kneading extrusion process can be employed to intimately combine the methanol synthesis catalyst (CZA) with a dehydration component.

- Peptization: The calcined CZA powder is physically mixed with a dehydration catalyst precursor, most commonly boehmite (γ-AlO(OH)). A peptizing agent, such as dilute nitric acid (HNO₃, 1-3 wt%), is added to the mixture. The acid disperses the components and creates a homogeneous, plastic paste [23].

- Extrusion: The paste is transferred to a piston or screw extruder and forced through a die to form cylindrical extrudates of a specific diameter (e.g., 2 mm).

- Drying and Calcination: The wet extrudates are dried at 393 K and finally calcined at a higher temperature (e.g., 723 K for 4 hours). This step serves to mechanically strengthen the extrudates and, crucially, to convert the boehmite binder into the active dehydration catalyst, γ-Al₂O₃ [23].

Precursor Phase Control through Synthesis Parameters

The formation of either hydrotalcite or zincian malachite is not arbitrary but is exquisitely sensitive to synthesis conditions, particularly the Cu/Al molar ratio and the precipitation pH.

- pH Control: As demonstrated in a study on Cu-Zn-Al-Zr systems, precipitation at a low pH (e.g., 6.0-7.0) favors the formation of zincian malachite as the dominant phase. Conversely, carrying out the precipitation at a higher pH (e.g., above 8.0) selectively yields a pure hydrotalcite-like phase. At intermediate pH values (e.g., 8.0), a mixture of both phases is typically observed [25].

- Metal Composition: The aluminum content is a decisive factor. A high Al content (e.g., lower Cu/Al ratio) promotes the formation of the layered hydrotalcite structure, which requires trivalent cations like Al³⺠within its layers. A lower Al content (e.g., higher Cu/Al ratio) favors the formation of zincian malachite or aurichalcite phases [23] [25].

The following workflow summarizes the experimental pathway for catalyst synthesis and phase control:

Results: Correlating Precursor Phase to Catalyst Properties and Performance

Structural and Textural Properties

The choice of precursor phase has a profound impact on the structural and textural properties of the final calcined and reduced catalyst.

Table 1: Influence of Precursor Phase on Catalyst Properties

| Property | Hydrotalcite (HTl)-Derived Catalyst | Zincian Malachite (ZM)-Derived Catalyst |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Precursor Phase | Layered Double Hydroxide (e.g., (Cu,Zn)₆Alâ‚‚CO₃(OH)â‚₆·4Hâ‚‚O) [23] | Zincian Malachite (e.g., (Cu,Zn)â‚‚CO₃(OH)â‚‚) [23] |

| Typical Synthesis Condition | Higher Al content, Higher pH (e.g., >8.0) [23] [25] | Lower Al content, Lower pH (e.g., 6.0-7.0) [23] [25] |

| Metallic Surface Area (Cu) | Higher (e.g., ~45 m²/g) [23] | Lower (e.g., ~31 m²/g) [23] |

| Cu Crystallite Size | Smaller, better dispersed [23] [25] | Larger [23] |

| Acidity | Generates a significant amount of surface acidic sites [23] | Lower density of acidic sites [23] |

| Proposed Active Site Structure | Intimate contact between highly dispersed Cu nanoparticles and defective ZnOx species, potentially with Zn migration onto Cu surfaces [24] [26] | Cu sites with less intimate contact with Zn species [23] |

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis is indispensable for identifying these precursor phases. A pure hydrotalcite precursor shows characteristic reflections at 2θ ~ 11.8°, 23.8°, and 34.6°, while a zincian malachite-rich precursor shows peaks at 2θ ~ 32.5°, 35.5°, and 38.7° [23]. After calcination, the oxides derived from the HTl precursor often maintain a higher dispersion of copper, leading to a larger metallic copper surface area—a parameter frequently correlated with higher activity in methanol synthesis and related reactions [23] [25].

Catalytic Performance in Syngas to DME (STD)

The structural advantages of a specific precursor phase translate directly into catalytic performance. In a study on (Cu-Zn-Al)/γ-Al₂O₃ hybrid catalysts for direct DME synthesis, the catalyst derived from a precursor with a higher ZM content (CZA(3.0)) exhibited superior activity.

Table 2: Catalytic Performance in Single-Step Syngas to DME

| Catalyst | Dominant Precursor Phase | CO Conversion (%) | DME Selectivity (%) | DME Yield (mol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹) x 10³ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CZA(1.5) | Hydrotalcite (HTl) | ~20 | ~42 | ~2.2 |

| CZA(2.5) | Mixed (HTl + ZM) | ~32 | ~48 | ~4.2 |

| CZA(3.0) | Zincian Malachite (ZM) | ~38 | ~55 | ~5.8 |

Data adapted from [23].

The data shows a clear trend: as the precursor phase transitions from pure HTl to ZM-rich, both CO conversion and DME selectivity increase significantly, resulting in a dramatically higher DME yield [23]. This was attributed to an optimal balance between a sufficient copper surface area and the strength and density of acid sites provided by the γ-Al₂O₃ dehydration component. Although the HTl-derived catalyst had a higher Cu surface area, the ZM-rich catalyst appeared to offer a more effective synergy between its metallic and acidic functions for the overall STD reaction [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental work in this field relies on a set of well-defined reagents and materials, each serving a specific function in the synthesis and evaluation process.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Catalyst Research |

|---|---|

| Copper Nitrate Trihydrate (Cu(NO₃)₂·3H₂O) | Primary source of Cu²⺠ions; the active metal component for hydrogenation after reduction [23]. |

| Zinc Nitrate Hexahydrate (Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) | Primary source of Zn²⺠ions; forms ZnO, which acts as a structural promoter and spacer, and may create active sites at the Cu-ZnO interface [23] [26]. |

| Aluminum Nitrate Nonahydrate (Al(NO₃)₃·9H₂O) | Source of Al³⺠ions; promotes formation of HTl structure, acts as a structural stabilizer, and enhances catalyst dispersion [23] [25]. |

| Sodium Carbonate (Na₂CO₃) | Precipitating agent and source of CO₃²⻠anions, which are incorporated into the hydroxycarbonate precursor structure [23] [25]. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Precipitating agent used to control and maintain the pH of the solution during coprecipitation [23] [25]. |

| Boehmite (γ-AlO(OH)) | Used as a binder in extrusion and as a precursor to the dehydration catalyst γ-Al₂O₃, which provides acidic sites for methanol dehydration [23]. |

| Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | Peptizing agent used during the kneading process to disperse catalyst particles and form a plastic paste for extrusion [23]. |

| N-Arachidonoyl-L-Serine-d8 | N-Arachidonoyl-L-Serine-d8 | GC-/LC-MS Internal Standard |

| Raloxifene dimethyl ester hydrochloride | Raloxifene Dimethyl Ester Hydrochloride|CA S 84449-82-1 |

Discussion: Mechanistic Insights and Deactivation Pathways

Activation and Working State of the Catalyst

The precursor phase not only influences the initial oxide catalyst but also dictates the morphology and interaction of the active components in their reduced, working state. The activation of the CZA catalyst in hydrogen is a complex process involving "drastic events" and "gradual changes" [24].

- Reduction of Copper Oxide: The first major event is the reduction of Cu²⺠in CuO to metallic CuⰠnanoparticles. The temperature of this reduction is pressure-dependent, occurring at lower temperatures with higher H₂ pressure [24].

- Zinc Oxide Transformation and Interaction: Accompanying copper reduction, the zinc-containing component undergoes significant changes. Operando X-ray spectroscopy studies have shown evidence for the formation of a Cu-Zn alloy (α-brass) or the migration of partially reduced zinc species onto the copper surface at temperatures above 470 K under H₂ flow [24]. This intimate contact between Cu and ZnOx is widely considered a key feature of the highly active catalyst.

- Final Working Structure: The working catalyst is thus a dynamic system comprising metallic copper nanoparticles in intimate contact with a defective and potentially "reducible" zinc oxide phase. Catalysts derived from HTl precursors, with their initially higher dispersion, are often better poised to form and maintain this critical interfacial structure under reaction conditions [25] [24] [26].

The following diagram illustrates the structural evolution from precursor to the active working catalyst:

Deactivation Mechanisms in Operating Conditions

Understanding the precursor phase is also critical for predicting and mitigating catalyst deactivation. Spent catalyst analysis reveals several microstructural failure modes:

- Sintering and Phase Segregation: Under the demanding conditions of CO₂ hydrogenation (e.g., high H₂O partial pressure at 30 bar), severe microstructural transformations occur. These include the segregation of ZnO and Al₂O₃ phases and the migration of copper, leading to the growth of larger Cu particles and a consequent loss of active surface area [26].

- Water-Induced Deactivation: The high-pressure Hâ‚‚O generated as a byproduct is a primary driver of deactivation. It can favor sintering and strongly adsorb onto and deactivate the Lewis acid sites crucial for methanol dehydration to DME [23] [26].

- Carbon Deposition: Though less common, carbon deposition on copper sites from side reactions can also contribute to activity decline over time [26].

Catalysts with a robust initial microstructure, often afforded by a well-formed HTl precursor, may exhibit superior resistance to these deactivation mechanisms by virtue of their higher thermal stability and better-anchored metal particles.

This case study unequivocally demonstrates that the phase transition from hydrotalcite to zincian malachite in Cu-Zn-Al catalysts is not a mere structural curiosity but a fundamental lever controlling catalytic performance. By varying the Cu/Al ratio and precipitation pH, synthesis can be directed to favor a specific precursor, which in turn dictates the copper dispersion, surface area, and acidic properties of the final catalyst. For the one-step synthesis of DME from syngas, a ZM-rich precursor was shown to provide a more effective synergy between the methanol synthesis and dehydration functions, leading to superior DME yields. However, the HTl precursor offers advantages in terms of generating higher Cu surface area and potentially enhanced stability. The activation process further refines this structure, creating a dynamic interface between Cu and ZnOx that is the hallmark of the active site. Therefore, a deep understanding of precursor phase chemistry is indispensable for the rational design of CZA catalysts, enabling precise optimization of their activity, selectivity, and stability for a targeted chemical transformation. This knowledge forms a critical chapter in the broader thesis of catalyst precursor transformation, providing a validated framework for advancing catalyst technology in sustainable chemistry.

Synthesis in Action: Innovative Methodologies and Biomedical Applications

The journey from a designed catalyst precursor to its active phase is a critical determinant of its ultimate performance in applications ranging from renewable energy conversion to environmental remediation. Precursor transformation encompasses the strategic chemical processes—including thermal activation, chemical reduction, and templating—that convert a stable, often inert, precursor material into a catalyst with targeted active sites. In the context of atomically dispersed catalysts, this transformation must be meticulously controlled to prevent the aggregation of metal atoms into nanoparticles, thereby preserving the unique geometric and electronic structures that confer high activity and selectivity. The significance of these synthesis routes is profoundly evident in the development of single-atom catalysts (SACs) and dual-atom catalysts (DACs), where the precise coordination environment of each metal atom directly dictates catalytic properties such as binding energy, reaction pathway, and stability [27] [28].

Emerging templating approaches provide a powerful means to exert this precise control during the precursor transformation process. These methods employ a sacrificial scaffold to dictate the morphology and local coordination structure of the final catalyst. A notable advancement is the use of low-cost, recyclable sodium chloride (NaCl) as a dynamic template. During high-temperature pyrolysis, the NaCl lattice confines metal atom migration to prevent aggregation. Upon melting, its ion dissociation facilitates the formation of specific asymmetric coordination environments, such as axial metal-chloride bonds, in addition to the in-plane metal-nitrogen coordination. This results in a well-defined active site, such as Cl1–Fe–N4, anchored within a 3D honeycomb-like carbon network, demonstrating how templating can simultaneously manage structure and coordination during precursor transformation [28].

Advanced synthesis methods are defined by their ability to achieve precise control over the atomic structure of catalytic active sites. The evolution from single-atom catalysts (SACs) to dual-atom catalysts (DACs) and beyond represents a frontier in catalysis research, driven by the need for more complex and cooperative active sites.

Dual-atom catalysts (DACs) represent a significant leap beyond SACs. While SACs feature isolated metal atoms, DACs consist of paired metal atoms, which can be homonuclear (e.g., Cu-Cu) or heteronuclear (e.g., Co-Cu). This configuration offers several distinct advantages rooted in the synergistic interaction between the two atoms. DACs provide a richer diversity of active sites, enabling more nuanced control over complex catalytic reactions. The metal-metal interaction in DACs can enhance electron and energy exchange, leading to optimized reaction pathways, improved catalytic efficiency, and superior selectivity. Furthermore, DACs allow for higher metal loading without sacrificing atomic dispersion, a key limitation of SACs where high metal content often leads to atom aggregation [27]. For instance, IrRu DACs achieve an exceptionally low overpotential of only 10 mV at 10 mA cmâ»Â² for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), while Co-Cu DACs reach a CO Faradaic efficiency of 99.1% at high current densities, underscoring their exceptional performance [27].

The synthesis of these advanced materials relies on a toolkit of sophisticated methods, each offering a different pathway for precursor transformation.

Table 1: Key Synthesis Methods for Atomically Dispersed Catalysts

| Synthesis Method | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Common Catalyst Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrolysis | High-temperature thermal decomposition of precursors in an inert atmosphere. | Scalable; wide applicability; enables graphitization of carbon supports. | SACs, DACs |

| Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) | Sequential, self-limiting surface reactions of gaseous precursors. | Atomic-scale precision over film growth and metal deposition. | SACs, DACs |

| Impregnation | Porous support is saturated with a metal-containing solution, followed by drying and activation. | Simple; cost-effective. | SACs |

| Templating (e.g., with NaCl) | Using a sacrificial material to control the morphology and coordination environment during synthesis. | Controls 3D morphology; tunes local metal coordination; some templates (e.g., NaCl) are recyclable. | SACs, High-Entropy SACs |

The choice of synthesis strategy is paramount in overcoming key challenges in DAC fabrication. These challenges include achieving precise control over metal atom placement on the support material, preventing aggregation or sintering during synthesis, and consistently producing high-quality materials. Methods like ALD offer exceptional control, while innovative approaches like the NaCl templating method provide a versatile and scalable route to create tailored coordination environments [27] [28].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Reproducibility is a cornerstone of scientific progress. The following section provides detailed, actionable protocols for key synthesis methods, enabling researchers to implement these advanced techniques in their own work.

NaCl-Templated Synthesis of Single-Atom Catalysts

This protocol outlines the synthesis of a Fe-based SAC with a Cl1–Fe–N4 coordination structure, as exemplified by the "Fe1CNCl" material [28].

- Primary Reagents: Iron(II) chloride tetrahydrate (FeCl₂·4H₂O, metal precursor), dicyandiamide (nitrogen and carbon precursor), glucose (additional carbon source), and sodium chloride (NaCl, template).

- Procedure:

- Precursor Solution Preparation: Dissolve FeCl₂·4H₂O, dicyandiamide, glucose, and NaCl in deionized water to form a homogeneous solution. The typical mass ratio can be adjusted, but a formulation with a high NaCl content (e.g., ~70-90 wt%) is used to act as the primary space-filler.

- Freeze-Drying: Subject the aqueous solution to freeze-drying (lyophilization) to remove water via sublimation. This process results in a solid, porous powder where the precursors are uniformly confined within the crystalline lattice of the NaCl template.

- High-Temperature Pyrolysis: Transfer the freeze-dried powder to a tube furnace and anneal under an inert atmosphere (e.g., argon) at a high temperature (e.g., 900°C) for a set time (e.g., 1-2 hours). The heating ramp rate should be controlled (e.g., 5°C/min).

- Key Transformation: Below its melting point (~801°C), the solid NaCl crystal lattice confines metal atoms, promoting the formation of in-plane M–Nx (x=4 or 6) coordination. Above 900°C, the molten NaCl dissociates into ions, facilitating the formation of an axial M–Cl bond, creating an asymmetric coordination sphere.

- Template Removal and Recovery: After the furnace cools to room temperature, the resulting composite is washed repeatedly with deionized water to dissolve and remove the NaCl template. The NaCl can be recovered from the wash water by evaporation with a reported recovery rate of up to 90.2%. The remaining solid is the desired SAC, which can be dried in an oven overnight.

- Characterization: The successful formation of atomically dispersed Fe sites in a Cl1–Fe–N4 configuration is confirmed by the absence of Fe-Fe bonds in EXAFS analysis and the presence of both Fe-N and Fe-Cl coordination paths. HAADF-STEM will show isolated bright spots, and XRD will show no crystalline metal nanoparticles [28].

Synthesis of Dual-Atom Catalysts via Pyrolysis

This protocol describes a general approach for preparing DACs using a pyrolysis-based method, which is a common and scalable strategy [27].

- Primary Reagents: Selected metal precursors (e.g., metal nitrates, chlorides, or acetylacetonates), nitrogen-rich organic ligands or polymers (e.g., phenanthroline, polyaniline), and a carbon support or carbon-generating precursor (e.g., carbon black, graphene oxide, ZIF-8).

- Procedure:

- Precursor Mixing: The metal precursors and nitrogen/carbon sources are thoroughly mixed. This can be achieved through:

- Impregnation: Incubating a porous carbon support with a solution containing the metal salts.

- One-Pot Synthesis: Co-dissolving or suspending all precursors (metal salts and organic ligands) in a solvent to form a homogeneous mixture or coordination polymer.

- Drying: The mixture is dried to remove the solvent, resulting in a solid precursor.

- Thermal Activation (Pyrolysis): The solid precursor is placed in a quartz boat and heated in a tube furnace under an inert (N₂, Ar) or reactive (NH₃) atmosphere. A typical pyrolysis temperature range for DACs is 700-1000°C, held for 1-4 hours. The specific temperature and time are critical and must be optimized to facilitate the formation of metal-nitrogen bonds while preventing the aggregation of metal atoms into clusters or nanoparticles.

- Post-Treatment: After pyrolysis, the material may be subjected to a mild acid wash (e.g., with dilute HCl or Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„) to remove any unstable, aggregated metal particles on the surface, leaving behind the more stable atomically dispersed DACs.

- Precursor Mixing: The metal precursors and nitrogen/carbon sources are thoroughly mixed. This can be achieved through:

- Characterization: Aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM is used to directly visualize diatomic pairs. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), including XANES and EXAFS, is essential for confirming the oxidation state and proving metal-metal coordination, which distinguishes DACs from isolated SACs [27].

Synthesis Workflow and Signaling Pathway Visualization

The transformation of precursors into active catalysts is a multi-stage process governed by specific chemical events. The following diagrams map these critical workflows and pathways.

SAC Synthesis via NaCl Templating

This diagram illustrates the step-by-step workflow for synthesizing single-atom catalysts using the recyclable NaCl template method.

Precursor to Active Phase Transformation

This pathway details the molecular-level events during the crucial pyrolysis stage, leading from a mixed precursor to an atomically dispersed active site.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The synthesis of advanced catalysts requires a carefully selected set of materials and reagents, each playing a specific role in the precursor transformation process.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Catalyst Synthesis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | FeCl₂·4Hâ‚‚O, Cobalt nitrate, Copper acetylacetonate | Source of catalytic metal atoms. The anion (Clâ», NO₃â») can influence the final coordination environment. |

| Nitrogen & Carbon Sources | Dicyandiamide (DCDA), Phenanthroline, Glucose | Forms the nitrogen-doped carbon matrix that stabilizes single metal atoms. Serves as the structural support. |

| Templating Agents | Sodium Chloride (NaCl), SiOâ‚‚ nanoparticles, MgO | Sacrificial material that controls the 3D morphology and porosity of the final catalyst. NaCl can also direct coordination. |

| Support Materials | Carbon Black, Graphene Oxide, Metal-Organic Frameworks (e.g., ZIF-8) | High-surface-area materials that can be impregnated with metals or pyrolyzed to create the conductive support. |