From Structure to Function: How Descriptors Predict Catalytic Activity and Selectivity

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of how molecular and material descriptors serve as powerful predictors for catalytic activity and selectivity, crucial for advancements in drug development and chemical synthesis.

From Structure to Function: How Descriptors Predict Catalytic Activity and Selectivity

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of how molecular and material descriptors serve as powerful predictors for catalytic activity and selectivity, crucial for advancements in drug development and chemical synthesis. We first establish the foundational principles of descriptors, from historical energy-based models to modern electronic and data-driven approaches. The discussion then progresses to methodological applications, detailing how researchers extract and utilize diverse descriptors in machine learning models to design novel catalysts and optimize reactions. The article further addresses key challenges in descriptor selection and model interpretation, offering strategies for troubleshooting and optimization. Finally, we present rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses of different descriptor types, equipping researchers with the knowledge to select appropriate tools and build reliable, predictive models for targeted catalytic outcomes.

The Language of Catalysis: Understanding Descriptor Fundamentals

In the fields of catalytic chemistry and drug discovery, the ability to predict molecular behavior from structure alone represents a fundamental paradigm. This whitepaper examines how computational descriptors serve as quantitative bridges connecting molecular structure to catalytic activity and selectivity. By translating complex molecular architectures into mathematically manipulatable numerical values, descriptors enable the construction of predictive models through quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) frameworks and machine learning approaches. We explore the development, classification, and application of molecular descriptors, presenting quantitative data on their predictive performance, detailed experimental protocols for their implementation, and visualization of the workflows connecting descriptors to functional outcomes. The insights provided herein establish descriptor-based modeling as an indispensable toolkit for researchers seeking to accelerate catalyst design and therapeutic development through computational prediction.

The central challenge in molecular design lies in predicting how structural features dictate functional behavior—whether catalytic turnover, pharmaceutical activity, or material properties. Molecular descriptors address this challenge by providing mathematical representations of molecular structures that quantify characteristics relevant to biological activity and catalytic function [1]. These descriptors form the foundation of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) and Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) models, which statistically correlate descriptor values with experimental outcomes [1].

The development of descriptors has evolved significantly from early physicochemical parameters to thousands of computed chemical descriptors leveraged through complex machine learning methods [1]. This evolution reflects the growing recognition that molecular function emerges from a complex interplay of structural features that can be captured mathematically. In catalysis research specifically, descriptors have enabled researchers to move beyond trial-and-error approaches toward rational design by identifying key property-performance correlations [2]. For drug development, descriptors facilitate the optimization of pharmacological profiles while predicting adverse effects and pharmacokinetic properties [3].

The "quantitative bridge" metaphor is particularly apt—descriptors transform qualitative structural concepts into numerical values that can be processed statistically, creating a passage from molecular input to functional output that is both predictable and mechanistically interpretable.

Classifying Molecular Descriptors: A Multi-Dimensional Toolkit

Molecular descriptors span multiple dimensions of structural representation, each with distinct advantages and limitations for predicting catalytic activity and selectivity. A comprehensive classification system organizes descriptors based on their information content and computational derivation.

Table 1: Classification of Molecular Descriptors by Dimension and Application

| Dimension | Description | Example Descriptors | Best Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0D | Constitutional descriptors requiring no structural information | Molecular weight, atom count, bond count | High-throughput screening, initial categorization | Limited structural insight |

| 1D | Fragments and functional groups | Presence/absence of pharmacophores, functional group counts | Similarity screening, toxicity prediction | No spatial arrangement |

| 2D | Topological descriptors from molecular connectivity | Molecular connectivity indices, Wiener index, graph representations | QSAR for congeneric series, drug discovery | Limited stereochemical information |

| 3D | Geometrical descriptors from 3D structure | Surface area, volume, polarizability, 3D-MoRSE descriptors | Catalytic site modeling, enzyme-substrate interactions | Conformational dependence |

| 4D | Incorporates ensemble of conformations | Interaction energy fields, molecular dynamics trajectories | Flexible docking, reaction mechanism studies | High computational cost |

The information content of descriptors ranging from 0D to 4D gradually enriches, with higher-dimensional descriptors capturing increasingly complex structural and electronic features [1]. Topological descriptors (2D) derived from molecular graph theory have proven particularly valuable in drug discovery, encoding connectivity patterns that correlate with biological activity [1]. For catalysis applications, electronic descriptors such as Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) charges and steric parameters including Sterimol values provide critical insights into reaction mechanisms and selectivity determinants [4].

Recent advances have introduced tailored descriptors for specific applications. In CO₂ cycloaddition catalysis, descriptors such as anion nucleophilicity and buried volume have been developed to capture the unique mechanistic requirements of the ring-opening and CO₂ insertion steps [5]. In electrocatalysis, traditional descriptors like hydrogen adsorption energy have been refined with surface charge information to improve predictive accuracy for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER) [6].

Mathematical Frameworks: From Descriptors to Predictive Models

The transformation of descriptor data into predictive models employs diverse mathematical frameworks, ranging from traditional regression techniques to advanced machine learning algorithms. The fundamental relationship can be expressed as:

Activity/Selectivity = f(D₁, D₂, ..., Dₙ)

Where D₁ to Dₙ represent the numerical values of n molecular descriptors.

Traditional Statistical Approaches

Early QSAR models primarily utilized multiple linear regression (MLR), principal component regression (PCR), and partial least squares (PLS) regression. These methods remain valuable for interpretable models with limited datasets. For example, in the development of acylshikonin derivatives as anticancer agents, PCR achieved impressive predictive performance (R² = 0.912, RMSE = 0.119) using electronic and hydrophobic descriptors [3].

Machine Learning and Deep Learning

Modern QSAR leverages both linear and nonlinear machine learning methods, with random forest, support vector machines, and neural networks demonstrating particular utility for complex descriptor-activity relationships [1]. The application of machine learning to CO₂ cycloaddition catalysis has yielded remarkable predictive accuracy (R² > 0.94, MAE = 2.2–2.8%) for catalyst performance [5].

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Descriptor-Based Predictive Models Across Applications

| Application Domain | Model Type | Key Descriptors | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticancer drug discovery (shikonin derivatives) | Principal Component Regression | Electronic, hydrophobic | R² = 0.912, RMSE = 0.119 | [3] |

| CO₂ cycloaddition catalysis | Random Forest | Anion nucleophilicity, buried volume | R² > 0.94, MAE = 2.2-2.8% | [5] |

| Enantioselective biocatalysis | Multivariate Linear Regression | NBO charges, Sterimol parameters, dynamic descriptors | Training R² = 0.82, MAE = 0.19 kcal/mol | [4] |

| Oxidative Coupling of Methane (OCM) | Meta-analysis with regression | Thermodynamic stability descriptors | p < 0.05 for performance difference | [2] |

| Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER) | Gaussian process microkinetic models | H binding energy, surface charge | Improved prediction of outliers (Pt, Cu) | [6] |

Mechanistically Explainable AI

Recent advances address the "black-box" nature of complex models through mechanistically explainable AI approaches. For predicting synergistic cancer drug combinations, Large Language Models (LLM) with retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) integrate biological knowledge graphs with experimental data to provide mechanistic rationales alongside predictions (F1 score = 0.80) [7]. Similarly, in enantioselective biocatalysis, statistical models relate structural features of both enzyme and substrate to selectivity, enabling predictions for out-of-sample substrates and mutants while maintaining interpretability [4].

Experimental Protocols: Implementing Descriptor-Based Workflows

Protocol 1: QSAR Model Development for Drug Discovery

This protocol outlines the workflow for developing predictive QSAR models for pharmaceutical applications, demonstrated in the evaluation of shikonin derivatives [3].

Compound Selection and Activity Data Collection

- Curate a structurally diverse set of 24 compounds with experimentally determined cytotoxic activities

- Ensure coverage of relevant chemical space for intended application

Descriptor Calculation

- Compute molecular descriptors using cheminformatics software (Dragon, RDKit, or OpenBabel)

- Include constitutional, topological, geometrical, and electronic descriptors

- Apply feature selection to reduce dimensionality (e.g., principal component analysis)

Model Building and Validation

- Split data into training and test sets (typically 70:30 or 80:20 ratio)

- Apply multiple modeling approaches (PLS, PCR, MLR) for comparison

- Validate models using cross-validation and external test sets

- Evaluate based on R², RMSE, and predictive accuracy metrics

Virtual Screening and Hit Identification

- Apply validated model to screen virtual compound libraries

- Prioritize compounds with predicted high activity for synthesis and testing

Mechanistic Interpretation

- Interpret significant descriptors in context of biological target

- Guide structural optimization based on descriptor-activity relationships

Protocol 2: Descriptor-Driven Catalyst Optimization for CO₂ Utilization

This protocol details the machine learning approach for optimizing catalysts for CO₂ cycloaddition, achieving yields >90% under ambient conditions [5].

Dataset Curation

- Compile experimental data from literature and high-throughput experimentation

- Include catalyst composition, reaction conditions, and performance metrics (yield, selectivity)

- Incorporate negative data (unsuccessful catalysts) to avoid bias

- Target dataset size >1000 entries for robust modeling

Descriptor Engineering

- Calculate catalyst-specific descriptors (e.g., ionic radius, electronegativity, coordination number)

- Compute reaction-condition descriptors (temperature, pressure, solvent environment)

- Apply domain knowledge to create tailored descriptors (e.g., buried volume for confinement effects)

Machine Learning Model Training

- Implement diverse algorithms (Random Forest, Neural Networks, Gaussian Processes)

- Utilize nested cross-validation to optimize hyperparameters

- Apply ensemble methods to improve predictive stability

Validation and Iterative Refinement

- Validate predictions through targeted experimentation

- Incorporate new data to retrain and improve models (active learning cycle)

- Assess transferability to related catalytic systems

Mechanistic Insight Extraction

- Apply feature importance analysis to identify critical descriptors

- Relate statistical models to fundamental catalytic principles

- Guide discovery of next-generation catalyst materials

Case Studies: Descriptors in Action

Predicting Enzyme Function and Mechanism

A quantitative analysis of functionally analogous enzymes (non-homologous enzymes with identical EC numbers) revealed that only 44% of enzyme pairs classified similarly by the Enzyme Commission had significantly similar overall reactions when comparing bond changes [8]. However, for those with similar overall reactions, 33% converged to similar mechanisms, with most pairs sharing at least one identical mechanistic step. This demonstrates how reaction similarity descriptors based on bond changes can refine functional classification and guide annotation of newly discovered enzymes.

Optimizing Biocatalyst Selectivity

In the engineering of Gluconobacter oxydans "ene"-reductase (GluER-T36A) for enantioselective radical cyclization, descriptors capturing electronic (NBO charges), steric (Sterimol values), and dynamic properties of both enzyme and substrate enabled the construction of predictive models (training R² = 0.82, validation R² = 0.73) [4]. The descriptors identified specific residue positions (W66, Y177) that modulated selectivity through flexibility and electronic effects, providing actionable guidance for protein engineering.

Oxidative Coupling of Methane (OCM) Catalyst Discovery

A meta-analysis of 1802 distinct OCM catalyst compositions revealed that high-performing catalysts provide two independent functionalities under reaction conditions: a thermodynamically stable carbonate and a thermally stable oxide support [2]. By developing physico-chemical descriptors that could be computed as a function of temperature and pressure, the analysis identified statistically significant property-performance correlations (p < 0.05) that explained why specific elemental combinations outperformed others.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Descriptor-Based Research

| Category | Item/Resource | Function/Application | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Platforms | Cheminformatics Suites | Calculate molecular descriptors | Dragon, RDKit, OpenBabel |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Compute electronic structure descriptors | Gaussian, ORCA, VASP | |

| Machine Learning Libraries | Build predictive QSAR models | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch | |

| Experimental Resources | Compound Libraries | Provide structural diversity for model training | ZINC, Enamine, in-house collections |

| High-Throughput Screening Systems | Generate experimental activity data | Automated reactors, robotic fluid handling | |

| Data Resources | Catalytic Databases | Source reaction performance data | Citeline Trialtrove, DrugComboDb |

| Knowledge Graphs | Provide biological context for interpretation | PrimeKG (proteins, pathways, diseases) | |

| Descriptor Types | Constitutional Descriptors | Basic molecular properties | Molecular weight, atom counts |

| Topological Descriptors | Capture connectivity patterns | Molecular connectivity indices | |

| Electronic Descriptors | Quantify charge distribution | NBO charges, Fukui indices | |

| Steric Descriptors | Measure spatial requirements | Sterimol parameters, buried volume |

The field of molecular descriptors continues to evolve toward increasingly sophisticated representations that capture complex structural and electronic features. Current research focuses on addressing key challenges including data scarcity (datasets often contain <1000 entries, leading to overfitting) and limited applicability domains (models performing poorly on structurally novel compounds) [1] [5]. Emerging approaches include the development of universal descriptor frameworks like UniDesc-CO2, which standardizes descriptors across studies and incorporates active learning to strategically expand datasets [5].

The integration of descriptors with mechanistically explainable AI represents another frontier, combining predictive power with biochemical insight [4] [7]. As demonstrated by the LLM-based framework for predicting synergistic drug combinations, future descriptor platforms will increasingly provide not just predictions but mechanistic rationales grounded in biological knowledge graphs [7].

In conclusion, molecular descriptors provide an essential quantitative bridge between molecular structure and function across diverse applications from catalytic chemistry to drug discovery. As descriptor design becomes more sophisticated and modeling approaches more powerful, these mathematical representations will play an increasingly central role in accelerating the design of novel catalysts and therapeutics through computational prediction. The researchers and drug development professionals who master descriptor-based methodologies will lead the next generation of rational molecular design.

The quest to understand and predict catalytic activity has long been a central pursuit in surface science and heterogeneous catalysis. This scientific journey has evolved from measuring macroscopic experimental parameters to elucidating fundamental electronic interactions at the atomic level. The field has progressively developed and utilized various descriptors—quantifiable properties that correlate with and predict catalytic performance—to guide catalyst design. This evolution represents a paradigm shift from trial-and-error experimentation toward rationally designed catalytic systems based on fundamental principles.

The progression of descriptors in catalysis research has followed a logical path from simple thermodynamic quantities to sophisticated electronic structure parameters. Initial reliance on experimental adsorption energy measurements has given way to computational approaches using density functional theory (DFT) and, ultimately, to electronic structure descriptors like the d-band center that provide deeper insight into the origin of catalytic behavior. This historical development has fundamentally transformed how researchers approach catalyst design, enabling more targeted and efficient discovery of materials for applications ranging from industrial chemical production to energy conversion and environmental remediation.

Foundational Concepts: Adsorption Energy as the Primary Descriptor

Defining Adsorption Energy

Adsorption energy represents the fundamental thermodynamic quantity describing the interaction strength between an adsorbate and a catalyst surface. Calculated using the formula:

Eads = E(A+B) - EA - EB [9]

where E(A+B) represents the total energy of the adsorption system, EA denotes the energy of the substrate, and E_B signifies the energy of the adsorbate. A negative adsorption energy value indicates a thermodynamically favorable adsorption process [9]. The magnitude of this energy allows researchers to distinguish between physisorption (characteristic of weak van der Waals forces, typically < 0.3 eV/atom) and chemisorption (involving stronger covalent or ionic bonding) [9] [10].

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

The determination of adsorption energies employs both experimental and computational approaches:

Experimental Approaches:

- Temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) measures adsorption strength through thermal desorption profiles

- Calorimetry directly measures heats of adsorption

- Kinetic analysis of reaction rates under varying conditions

Computational Approaches using Density Functional Theory:

- DFT simulations calculate adsorption energies via the difference between the total energy of the adsorbate-substrate complex and the sum of energies of the isolated components [9]

- Geometric relaxation of the adsorption system follows three convergence criteria: energy, force, and atomic displacement [9]

- Adsorption site testing identifies the lowest energy configuration where adsorbates are most likely to adhere [9]

Table 1: Methodologies for Adsorption Energy Determination

| Method Type | Specific Technique | Key Output | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Temperature-Programmed Desorption | Desorption energy profiles | Reflects weakest binding energy in complex systems |

| Experimental | Calorimetry | Heat of adsorption | Direct thermodynamic measurement |

| Computational | Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Adsorption energy from first principles | Requires appropriate exchange-correlation functionals |

| Computational | Site Testing | Identification of preferred adsorption sites | Computationally intensive for large systems |

The Advent of Electronic Structure Descriptors

Limitations of Adsorption Energy

While adsorption energy provides crucial thermodynamic information, it presents significant limitations as a standalone descriptor. As a macroscopic parameter, it offers limited fundamental insight into the electronic origins of catalytic behavior. Each adsorption energy calculation is computationally expensive, making high-throughput screening of candidate materials challenging. Additionally, adsorption energy measurements and calculations often show considerable oscillations with cluster size and shape in computational models [11], requiring careful convergence testing. These limitations motivated the search for more fundamental electronic descriptors that could provide predictive capability and deeper theoretical understanding.

The d-Band Center Theory

The development of the d-band center model by Hammer and Nørskov represented a transformative advance in catalytic descriptor theory [12] [13] [14]. This model connects the catalytic activity of transition metal surfaces to their electronic structure through a single parameter:

The d-band center (ε_d) is defined as the first moment of the d-band density of states, representing the average energy of the d-states relative to the Fermi level [12].

The fundamental premise of this theory states that an upward shift of the d-band center correlates with stronger adsorbate binding due to the formation of a larger number of empty anti-bonding states [12]. This relationship arises because the d-states of transition metals primarily govern their surface reactivity, particularly in forming bonds with adsorbates.

The theoretical foundation combines elements from:

- The Newns-Anderson model describing the interaction between adsorbate states and metal valence bands

- Effective medium theory relating adsorption energy to local electron density and changes in one-electron states of the surface [12]

Table 2: Comparison of Catalytic Descriptors

| Descriptor | Fundamental Basis | Computational Cost | Predictive Capabilities | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption Energy | Thermodynamic measurement of adsorbate-surface binding | High (direct DFT calculation) | Direct measurement of binding strength | Limited fundamental insight, computationally expensive |

| d-Band Center | Average energy of d-states relative to Fermi level | Moderate (requires DOS calculation) | Correlates with trends in adsorption strength across metals | Less accurate for magnetic surfaces, certain adsorbates |

| Generalized d-Band Center | d-Band center normalized by coordination effects | Moderate | Improved prediction for nanoparticles and alloys | More complex calculation |

| BASED Theory | Bonding/anti-bonding orbital electron intensity difference | High (requires detailed electronic analysis) | High precision for abnormal d-band cases | Very new approach, limited validation |

Methodological Protocols for Descriptor Determination

Computational Determination of the d-Band Center

The standard methodology for calculating the d-band center employs Density Functional Theory with the following protocol:

Computational Parameters:

- Use of projector augmented wave (PAW) method as implemented in VASP [13]

- Generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional [13]

- Gamma-centered k-points 3×3×1 for Brillouin zone sampling [13]

- Cutoff energy of 500 eV [13]

- Grimme's DFT-D3 method for van der Waals corrections [13]

- Convergence criteria: energy change < 0.001 eV/atom and force on each atom < 0.01 eV/Å [13]

Calculation Workflow:

- Bulk Optimization: Optimize the lattice constant of the bulk metal

- Surface Construction: Create surface slab models with appropriate thickness (typically 3-5 layers)

- Surface Relaxation: Fully relax the surface structure while fixing bottom layers

- Electronic Structure: Calculate the density of states (DOS) project onto d-orbitals of surface atoms

- Center Determination: Compute the d-band center as the first moment of the d-band DOS

Advanced Descriptor Development

Recent methodological advances have addressed limitations in the conventional d-band model:

Spin-Polarized d-Band Center: For magnetic transition metal surfaces, the conventional d-band model is inadequate. The generalized approach considers two d-band centers (εd↑ and εd↓) for majority and minority spin electrons, respectively [12]. The adsorption energy in this model incorporates competitive spin-dependent metal-adsorbate interactions [12].

BASED Theory: The recently proposed Bonding and Anti-bonding Orbitals Stable Electron Intensity Difference (BASED) theory addresses abnormal phenomena where materials with high d-band centers exhibit weaker adsorption capability [13]. This descriptor provides improved correlation with adsorption energies (R² = 0.95) compared to conventional d-band center models [13].

Evolution of Catalytic Descriptors

Applications and Validation Studies

Case Study: HMX Combustion Catalysis

Research on catalytic decomposition of HMX (octahydro-1,3,5,7-tetranitro-1,3,5,7-tetrazocine) demonstrates the practical application of adsorption energy descriptors. Studies calculated adsorption energies of HMX and oxygen atoms on 13 metal oxides using DMol³ [15]. The relationship between adsorption energy and experimental T₃₀ values (time required for decomposition depth to reach 30%) was depicted as a volcano plot, enabling prediction of T₃₀ values for other metal oxides based on their adsorption energies [15]. This approach successfully predicted apparent activation energy data for HMX/MgO, HMX/SnO₂, HMX/ZrO₂, and HMX/MnO₂ systems, validating the predictive capability of adsorption energy calculations [15].

Oxidative Coupling of Methane (OCM)

A comprehensive meta-analysis of OCM catalysis literature demonstrated the power of descriptor-based analysis. By combining literature data (1802 catalyst compositions) with physicochemical descriptor rules and statistical tools, researchers developed models dividing catalysts into property groups based on hypothesized descriptors [2]. The final model indicated that high-performing OCM catalysts provide, under reaction conditions, two independent functionalities: a thermodynamically stable carbonate and a thermally stable oxide support [2]. This study exemplified how descriptor-based analysis can extract fundamental design principles from large, heterogeneous datasets.

Machine Learning with Descriptors

The d-band center has emerged as a crucial feature in machine learning approaches to catalysis. In predicting CO adsorption on Pt nanoparticles, using a generalized d-band center energy normalized by coordination number as the sole descriptor achieved an absolute mean error of just -0.23 (±0.04) eV from DFT-calculated adsorption energies [14]. Similarly, incorporating d-band centers of bonding metal atoms in feature spaces has enabled screening of bimetallic catalysts for methanol electro-oxidation by predicting CO and OH adsorption energies [14]. These applications demonstrate how electronic structure descriptors facilitate high-throughput computational catalyst screening.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Descriptors in Catalysis Research

| Tool/Descriptor | Function/Role | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| VASP | Quantum mechanics DFT package for electronic structure calculations | Primary tool for calculating adsorption energies, d-band centers, and electronic properties |

| DMol³ | Density functional theory code for molecular and solid-state systems | Adsorption energy calculations for molecules on surfaces |

| Adsorption Energy (E_ads) | Quantitative measure of adsorbate-surface binding strength | Fundamental descriptor for catalytic activity; input for volcano relationships |

| d-Band Center (ε_d) | Average energy of d-states relative to Fermi level | Electronic descriptor for transition metal surface reactivity |

| Generalized d-Band Center | d-Band center normalized by coordination effects | Improved descriptor for nanoparticles and uneven surfaces |

| BASED Descriptor | Bonding/anti-bonding orbital electron intensity difference | Addressing abnormal cases where d-band theory fails |

| Spearman Correlation (ρ) | Non-parametric statistical measure of monotonic relationships | Assessing descriptor-performance correlations in heterogeneous datasets |

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant advances, descriptor-based catalysis research faces several challenges. The d-band center model shows limitations for surfaces with high spin polarization [12], materials with nearly full d-bands [12], and cases where the d-band is discontinuous such as in small metal particles [13]. These limitations have motivated development of more sophisticated descriptors like the spin-polarized d-band model and BASED theory [12] [13].

Future directions in descriptor development include:

Multi-Descriptor Approaches: Combining electronic, geometric, and thermodynamic descriptors in unified models to capture complementary aspects of catalytic behavior [16].

Machine Learning Integration: Using electronic structure descriptors as features in machine learning models to predict catalytic properties across vast compositional spaces [16] [14].

Dynamic Descriptors: Developing descriptors that account for catalyst evolution under operating conditions, moving beyond static surface models.

High-Throughput Computation: Leveraging descriptors for rapid screening of catalyst libraries, accelerating discovery cycles [14].

The historical progression from adsorption energy to electronic structure descriptors represents a fundamental maturation in catalysis science. This evolution has transformed catalyst design from empirical art toward predictive science, enabling more rational and efficient development of catalysts for addressing global energy and sustainability challenges.

In computational materials science and drug discovery, descriptors are quantitative representations of a material's or molecule's key characteristics that determine its properties and performance. In the context of a broader thesis on predicting catalytic activity and selectivity, descriptors serve as crucial intermediary links between a catalyst's fundamental structure and its resulting catalytic function. The accurate prediction of catalytic behavior hinges on identifying descriptors that effectively capture the underlying physical and electronic properties governing adsorption energies, reaction pathways, and transition states. By establishing mathematical relationships between descriptors and catalytic performance, researchers can rapidly screen vast material spaces, identify promising candidates, and gain fundamental insights into reaction mechanisms, thereby accelerating the development of efficient catalysts for energy applications and pharmaceutical compounds.

This guide provides a comprehensive technical framework for categorizing and applying descriptors in catalytic research, focusing on three fundamental approaches: energy-based, electronic structure-based, and data-driven descriptor methodologies. Each category offers distinct advantages and captures different aspects of catalytic behavior, enabling researchers to select the most appropriate descriptors based on their specific catalytic system, available computational resources, and desired prediction accuracy. The following sections detail each descriptor category, present quantitative comparison data, outline experimental protocols, and provide visualization of workflows to facilitate practical implementation in catalytic activity and selectivity research.

Energy-Based Descriptors

Energy-based descriptors fundamentally capture the thermodynamic interactions between catalyst surfaces and reacting species. These descriptors directly quantify the energy landscape of catalytic processes, making them particularly valuable for predicting activity and selectivity based on the Sabatier principle, which states that optimal catalysts bind reaction intermediates neither too strongly nor too weakly.

Adsorption Energy

Adsorption energy is the most widely used energy-based descriptor, representing the strength of interaction between an adsorbate (reactant, intermediate, or product) and a catalyst surface. It is calculated as the energy difference between the adsorbed system and the sum of the clean surface and isolated adsorbate energies: Eads = E(surface+adsorbate) - Esurface - Eadsorbate.

Table 1: Characteristic Values of Adsorption Energies for Key Intermediates

| Catalyst Type | *O Adsorption (eV) | *H Adsorption (eV) | *CO Adsorption (eV) | *OH Adsorption (eV) | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt-based alloys | -3.2 to -4.1 | -2.7 to -3.3 | -1.4 to -2.1 | -2.9 to -3.6 | Fuel cell ORR |

| Cu/ZnO systems | -2.8 to -3.5 | -2.4 to -2.9 | -0.6 to -1.2 | -2.1 to -2.7 | CO₂ to methanol |

| Ni-Fe alloys | -3.5 to -4.3 | -2.6 to -3.1 | -1.8 to -2.4 | -3.1 to -3.8 | Water electrolysis |

| High-entropy alloys | -3.1 to -4.5 | -2.5 to -3.4 | -1.2 to -2.3 | -2.7 to -3.7 | Broad screening |

Advanced Energy Descriptors

Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED)

For complex catalysts with multiple facets and binding sites, the single adsorption energy value provides an incomplete picture. The Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED) descriptor addresses this limitation by capturing the spectrum of adsorption energies across various facets and binding sites of nanoparticle catalysts [17]. AED is particularly valuable for representing industrial catalysts that comprise nanostructures with diverse surface facets, as it fingerprints the material's catalytic properties by aggregating binding energies for different catalyst facets, binding sites, and adsorbates.

Methodology for AED Calculation:

- Surface Generation: Generate multiple surface terminations for a material across a defined range of Miller indices (e.g., {-2, -1, 0, 1, 2}).

- Configuration Engineering: Create surface-adsorbate configurations for the most stable surface terminations across all facets.

- Energy Optimization: Optimize these configurations using computational methods (DFT or MLFF).

- Distribution Construction: Aggregate the calculated adsorption energies to form a probability distribution representing the material's adsorption landscape.

In a recent study applying this methodology to CO₂ to methanol conversion, researchers computed an extensive dataset of over 877,000 adsorption energies across nearly 160 materials, focusing on key intermediates including *H, *OH, *OCHO, and *OCH₃ [17].

Activity Descriptors from Scaling Relations

Based on linear scaling relationships between adsorption energies of different intermediates, activity descriptors such as the theoretical overpotential for electrochemical reactions provide a simplified metric for catalyst activity. For the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR), the adsorption energy of *OH (ΔE_OH) often serves as an effective activity descriptor, with optimal values typically around 0.1-0.3 eV weaker than on Pt(111).

Electronic Structure Descriptors

Electronic structure descriptors capture the fundamental quantum mechanical properties of catalysts that govern their ability to form and break chemical bonds. These descriptors provide deeper insight into the origin of catalytic activity and often enable faster screening than direct energy calculations.

d-Band Theory Descriptors

For transition metal catalysts, d-band theory provides the most widely applied electronic structure descriptors. The central premise is that the electronic states derived from the d-levels of surface atoms primarily control chemisorption properties.

Table 2: Electronic Structure Descriptors for Transition Metal Catalysts

| Descriptor | Physical Meaning | Calculation Method | Correlation with Adsorption | Typical Range (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| d-band center (ε_d) | Average energy of d-states relative to Fermi level | Projected density of states | Higher ε_d → stronger adsorption | -4.0 to -1.5 |

| d-band width | Energy span of d-states | Second moment of d-projected DOS | Wider d-band → weaker adsorption | 3.0 to 7.0 |

| d-band filling | Fraction of occupied d-states | Integration of d-DOS up to E_F | Higher filling → weaker adsorption | 0.3 to 0.9 |

| d-band upper edge | Highest energy of d-states | Maximum of d-projected DOS | Direct impact on antibonding states | -2.0 to 0.5 |

The d-band center (ε_d) represents the average energy of the d-electron states relative to the Fermi level. A higher d-band center (closer to the Fermi level) correlates with stronger adsorbate binding, while a lower d-band center correlates with weaker binding [18]. Additional descriptors such as d-band width and the position of the upper d-band edge provide enhanced predictive understanding of catalytic behavior by capturing subtle variations in electronic structure [18].

Methodology for d-Band Descriptor Calculation:

- Perform DFT calculation on catalyst surface model

- Project electronic density of states onto d-orbitals of surface atoms

- Calculate d-band center: εd = ∫ E ρd(E) dE / ∫ ρ_d(E) dE

- Determine d-band width from second moment of d-projected DOS

- Compute d-band filling by integrating occupied d-states

Quantum Chemical Descriptors

For molecular catalysts and pharmaceutical applications, quantum chemical descriptors derived from molecular orbital theory provide valuable predictive power. The QUantum Electronic Descriptor (QUED) framework integrates both structural and electronic data of molecules to develop machine learning models for property prediction [19]. QUED incorporates molecular orbital energies, DFTB energy components, and other electronic features that have proven influential for predicting toxicity and lipophilicity in pharmaceutical applications.

Key quantum chemical descriptors include:

- Fukui indices: Measuring susceptibility to nucleophilic/electrophilic attack

- Molecular orbital energies: HOMO-LUMO gap, ionization potential, electron affinity

- Electrophilicity index: Overall electrophilic power of molecules

- Partial atomic charges: Charge distribution affecting binding interactions

SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis of predictive models has revealed that molecular orbital energies and DFTB energy components are among the most influential electronic features in QUED [19].

Data-Driven Descriptors

Data-driven descriptors leverage machine learning algorithms to identify complex, multidimensional relationships in high-dimensional data that may not be captured by traditional physical descriptors. These approaches are particularly valuable for navigating vast material spaces and capturing synergistic effects in complex catalyst systems.

Machine-Learned Descriptors

Machine learning models can automatically generate optimized descriptors from raw structural or compositional data. Graph neural networks directly operate on atomic structures, learning representations that capture both geometric and electronic features without requiring pre-defined descriptors [20] [18]. These models can predict catalytic properties with accuracy approaching DFT calculations but at a fraction of the computational cost.

The body-attached-frame descriptors represent an innovative approach that respects physical symmetries while maintaining a nearly constant descriptor-vector size as alloy complexity increases [20]. These easy-to-optimize descriptors enable efficient machine learning models for predicting electron density and energy across composition space.

Methodology for Machine-Learned Descriptor Development:

- Data Collection: Compile diverse dataset of catalyst structures and properties

- Representation Selection: Choose appropriate featurization (Coulomb matrices, graph representations, etc.)

- Model Training: Train neural networks to predict target properties

- Descriptor Extraction: Use latent space representations as learned descriptors

- Validation: Assess descriptor performance on hold-out datasets

Feature-Optimized Descriptors

Advanced feature selection techniques can identify optimal descriptor combinations from large pools of candidate features. The SISSO (Sure Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator) method combines sure independence screening with compressed sensing to identify optimal nonlinear descriptor expressions from enormous feature spaces [17].

In catalyst research, Bayesian Active Learning efficiently explores descriptor spaces by leveraging uncertainty quantification capabilities of Bayesian Neural Networks, significantly reducing training data requirements [20]. Compared to strategic tessellation of composition space, Bayesian Active Learning reduced the number of training data points by a factor of 2.5 for ternary (SiGeSn) and 1.7 for quaternary (CrFeCoNi) systems [20].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

Workflow for Descriptor-Based Catalyst Screening

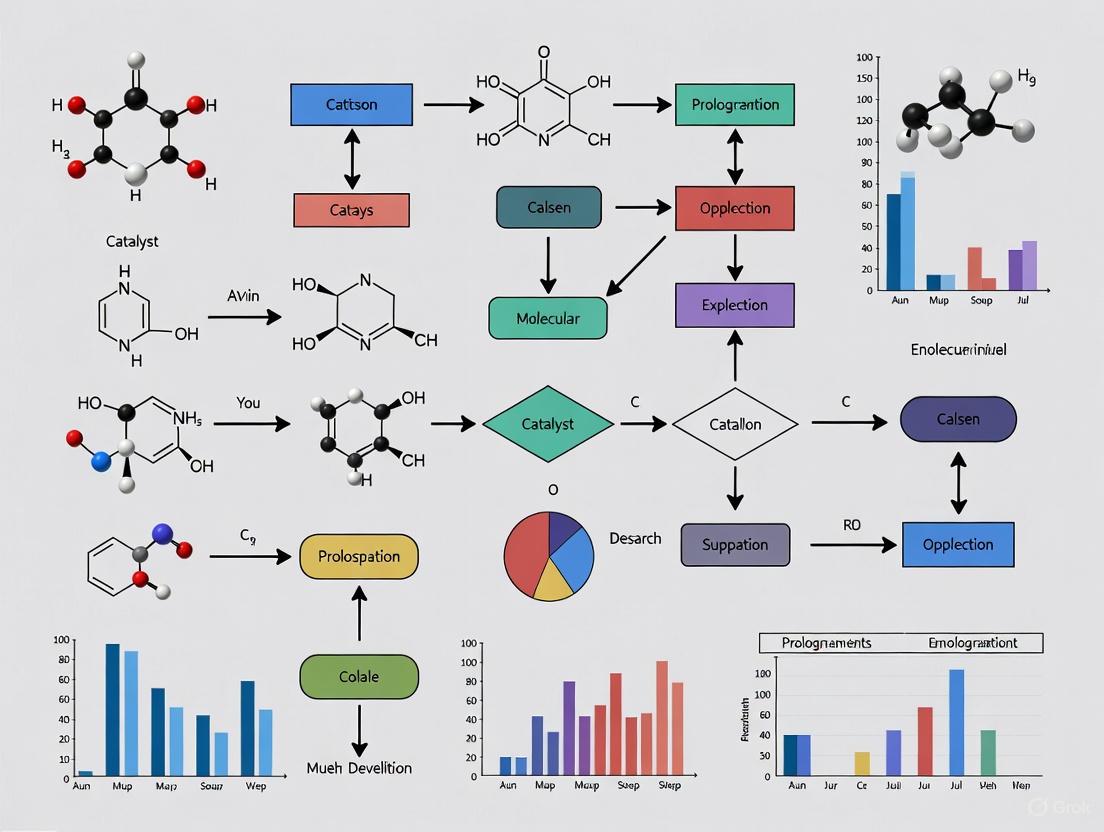

The following Graphviz diagram illustrates an integrated workflow for descriptor-based catalyst discovery, combining computational and experimental approaches:

Descriptor-Based Catalyst Discovery Workflow

Validation Protocols for Predictive Models

Robust validation is essential for ensuring the reliability of descriptor-based predictive models. The following protocols should be implemented:

Statistical Validation for QSAR Models [21]:

- Data Division: Randomly split compounds into training (∼66%) and test sets

- Internal Validation: Apply leave-one-out (LOO) or leave-many-out (LMO) cross-validation

- External Validation: Evaluate model on completely independent test set

- Statistical Metrics: Calculate R², Q², RMSE, and MAE for both training and test sets

- Applicability Domain: Define chemical space where model provides reliable predictions

Descriptor Validation for Catalytic Properties [17]:

- Benchmarking: Compare MLFF predictions with explicit DFT calculations for selected materials

- Error Analysis: Calculate mean absolute error (MAE) for adsorption energies (target: <0.2 eV)

- Statistical Sampling: Sample minimum, maximum, and median adsorption energies for each material-adsorbate combination

- Outlier Detection: Apply statistical methods (Random Forest, SHAP analysis) to identify critical electronic descriptors and anomalous predictions [18]

Table 3: Essential Resources for Descriptor-Based Catalysis Research

| Category | Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Databases | Open Catalyst Project (OCP) | Provides pre-trained ML force fields | Rapid adsorption energy calculation [17] |

| Materials Project | Database of crystal structures & properties | Initial catalyst screening space definition [17] | |

| QM7-X dataset | Quantum mechanical properties of molecules | Validation of quantum chemical descriptors [19] | |

| Software & Tools | QUED GitHub Repository | Quantum Electronic Descriptor framework | Pharmaceutical property prediction [19] |

| SISSO algorithm | Feature selection from large descriptor spaces | Identification of optimal descriptor expressions [17] | |

| OrbiTox platform | Read-across and QSAR modeling | Regulatory toxicology assessment [22] | |

| Experimental Validation | High-throughput synthesis platforms | Parallel catalyst preparation | Experimental validation of predictions |

| In situ/operando characterization | Monitoring catalyst under reaction conditions | Verification of predicted mechanisms |

The strategic categorization and application of descriptors—energy-based, electronic structure-based, and data-driven—provide powerful frameworks for predicting catalytic activity and selectivity. Energy-based descriptors like adsorption energy distributions offer direct thermodynamic insights, electronic structure descriptors such as d-band centers reveal fundamental quantum mechanical origins of catalytic behavior, and data-driven descriptors leverage machine learning to capture complex, multidimensional relationships. The integration of these complementary approaches, supported by robust computational workflows and validation protocols, enables accelerated discovery and optimization of catalysts for energy applications and pharmaceutical development. As descriptor methodologies continue to evolve through advances in machine learning and high-throughput computation, they will play an increasingly pivotal role in bridging the gap between fundamental catalytic principles and practical catalyst design.

In the rational design of catalysts, electronic descriptors provide a powerful bridge between a material's fundamental properties and its macroscopic catalytic performance. Among these, the d-band center theory stands as a cornerstone concept in heterogeneous catalysis, establishing a robust framework for predicting adsorption energies and reaction pathways. This guide examines the central role of electronic structure analysis, with specific focus on d-band center position, as a descriptor for predicting catalytic activity and selectivity. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these descriptors enables accelerated screening of catalytic materials and provides deeper mechanistic insights essential for designing targeted therapeutic agents and sustainable chemical processes.

The predictive power of electronic descriptors extends beyond fundamental science into practical applications. Modern approaches combine density functional theory (DFT) calculations with machine learning (ML) methods to rapidly screen bimetallic catalysts using readily available metal properties as features [23]. This synergy between electronic structure theory and data-driven modeling has significantly reduced the computational cost associated with traditional catalyst discovery, allowing researchers to navigate the vast compositional space of potential materials with unprecedented efficiency.

Theoretical Foundations of d-Band Center Theory

Basic Principles and Electronic Structure Origins

The d-band center theory fundamentally describes the energy position of the d-band electronic states relative to the Fermi level in transition metal systems. Mathematically, this is represented as the first moment of the d-band density of states (DOS):

[ \epsilond = \frac{\int{-\infty}^{\infty} E \cdot \rhod(E) dE}{\int{-\infty}^{\infty} \rho_d(E) dE} ]

where ( \epsilond ) represents the d-band center and ( \rhod(E) ) denotes the d-projected density of states at energy E. This descriptor powerfully correlates with adsorption strength because the d-band center position determines the energy alignment between metal d-states and adsorbate molecular orbitals. When the d-band center shifts closer to the Fermi level, stronger bonding occurs with adsorbates due to enhanced overlap and reduced antibonding state occupancy [23].

The theoretical foundation rests on the Newns-Anderson model of chemisorption, which describes the broadening and shifting of adsorbate states through hybridization with metal bands. In this framework, the d-band center serves as a simplified metric that captures essential physics of the surface-adsorbate interaction. For transition metals, the d-states primarily govern chemical bonding at surfaces, as they are more localized than sp-states and thus more sensitive to the local chemical environment. This localization makes the d-band center an exceptionally sensitive descriptor for catalytic properties across different metal compositions and structures.

Relationship to Catalytic Properties

The d-band center position exhibits systematic relationships with key catalytic performance metrics:

- Adsorption Energy Correlation: A higher-lying d-band center (closer to the Fermi level) typically strengthens adsorbate binding, while a lower-lying d-band center weakens it. This correlation applies across various adsorbates including CO, OH, O, and H [23].

- Reaction Pathway Determination: The selectivity of competing reaction channels often depends on the relative adsorption strengths of key intermediates, which are governed by d-band center positions.

- Activity Optimization: The Sabatier principle dictates that optimal catalysts bind reactants neither too strongly nor too weakly, creating a "volcano plot" relationship when activity is plotted against d-band center position.

For bimetallic systems, the d-band center provides crucial insights into ligand and strain effects. Alloying a host metal with a guest metal modifies the d-band center through both electronic ligand effects (direct electron donation/withdrawal) and geometric strain effects (changing interatomic distances). These combined effects enable precise tuning of adsorption properties for specific catalytic applications, such as minimizing CO poisoning while maintaining desired reaction activity [23].

Computational Methodologies and Protocols

Density Functional Theory Calculations

DFT serves as the foundational computational method for electronic descriptor calculation. The following protocol outlines key steps for determining d-band centers:

Structure Optimization:

- Build initial surface models (e.g., (111)-terminated slabs for FCC metals) with appropriate thickness (typically 3-5 atomic layers).

- Employ convergence tests for plane-wave cutoff energy and k-point sampling to ensure total energy convergence within 1 meV/atom.

- Relax atomic positions until residual forces are below 0.01 eV/Å.

Electronic Structure Calculation:

- Perform self-consistent field calculations to obtain converged charge density.

- Select appropriate exchange-correlation functional (PBE for structural properties, RPBE for adsorption energies).

- Calculate density of states with enhanced k-point sampling (至少 11×11×1 Monkhorst-Pack grid for surfaces).

d-Band Center Determination:

- Project density of states onto d-orbitals of surface atoms.

- Integrate d-projected DOS according to the d-band center formula.

- Reference energy values to the Fermi level of the system.

For accurate adsorption energy calculations, slab models should include sufficient vacuum spacing (至少 15 Å) to prevent periodic interactions, and the bottom layers may be fixed at bulk positions while relaxing the surface layers.

Machine Learning Approaches

Machine learning methods complement DFT by enabling rapid prediction of electronic descriptors and binding energies based on readily available features [23]. The following workflow describes the ML approach:

Table 1: Machine Learning Models for Descriptor Prediction

| Model Category | Specific Algorithms | Performance for CO Binding Energy (RMSE) | Performance for OH Binding Energy (RMSE) | Computational Time (for 25,000 fits) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Models | Linear Regression (LR) | 0.150-0.300 eV | 0.250-0.400 eV | ~5 minutes |

| Kernel Methods | SVR, KRR | 0.120-0.200 eV | 0.220-0.350 eV | ~15-30 minutes |

| Tree-Based Ensemble | RFR, ETR | 0.100-0.180 eV | 0.210-0.320 eV | ~20-40 minutes |

| Gradient Boosting | xGBR, GBR | 0.091 eV (CO), 0.196 eV (OH) | ~30-60 minutes |

Feature Selection: Utilize readily available elemental properties as input features, including:

- Atomic number, period, group

- Atomic radius, atomic mass

- Electronegativity, ionization energy

- Boiling point, melting point, heat of fusion

- Density, surface energy [23]

Model Training:

- Divide dataset into training and testing subsets (typical ratio: 70-80% training)

- Implement hyperparameter optimization via grid search or Bayesian optimization

- Employ k-fold cross-validation to prevent overfitting

Performance Validation:

- Evaluate models using root mean square error (RMSE) and coefficient of determination (R²)

- Compare ML-predicted binding energies with DFT-calculated values

- The extreme Gradient Boosting Regressor (xGBR) has demonstrated superior performance with R² scores of 0.970 and 0.890 for CO and OH binding energies, respectively [23]

Experimental Validation and Application Case Studies

Cu-Based Bimetallic Alloys for Formic Acid Decomposition

Formic acid decomposition represents a significant reaction for hydrogen storage, where catalyst selectivity between dehydrogenation (H₂ + CO₂) and dehydration (CO + H₂O) pathways is crucial. Pure copper exhibits selectivity for dehydrogenation but with limited activity, while Cu-based bimetallic alloys such as Cu₃Pt demonstrate enhanced performance while inhibiting CO poisoning [23].

In this application, CO and OH binding energies serve as key descriptors predicted through machine learning models trained on elemental properties. The ML-predicted binding energies showed remarkable agreement with DFT-calculated values, with mean absolute errors of just 0.02-0.03 eV [23]. These descriptor values were subsequently used in ab initio microkinetic models (MKM) to efficiently screen A₃B-type bimetallic alloys, significantly accelerating the catalyst discovery process.

The study employed eight different ML models classified as linear, kernel, and tree-based ensemble models. The extreme gradient boosting regressor (xGBR) outperformed all other models with RMSE values of 0.091 eV and 0.196 eV for CO and OH binding energy predictions, respectively, on (111)-terminated A₃B alloy surfaces [23]. This accuracy in descriptor prediction enables reliable forecasting of catalytic performance without resource-intensive DFT calculations for each candidate material.

Extension to Other Catalytic Systems

The application of d-band center and related electronic descriptors extends to numerous catalytic processes:

- CO₂ Reduction Reactions: Selectivity toward specific reduction products (CO, formate, methane, ethylene) correlates with d-band center position of copper-based catalysts [23].

- Methanol Electro-oxidation: Activity trends across platinum-based catalysts reflect d-band center modifications through alloying.

- Reverse Water Gas Shift Reactions: Cu-based catalysts with intermediate CO binding energy demonstrate optimal performance [23].

Table 2: Electronic Descriptors for Catalytic Reactions

| Reaction | Key Descriptors | Optimal Descriptor Range | Catalyst Materials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formic Acid Decomposition | CO binding energy, OH binding energy | Intermediate CO binding, Weak OH binding | Cu₃M (M = Pt, Pd, Ni) |

| CO₂ Reduction | CO binding energy, O binding energy | Moderate CO binding for C₁ products, Weak for C₂+ products | Cu, Cu-Ag, Cu-Au |

| Steam Methane Reforming | C binding energy, O binding energy | Weak C binding, Intermediate O binding | Ni, Ni-Fe, Co-Ni |

| Methanol Electro-oxidation | d-band center, CO binding energy | Lower d-band center for CO tolerance | Pt, Pt-Ru, Pt-Sn |

In each application, descriptor-based analysis enables rapid screening of candidate materials before experimental validation. The integration of electronic descriptors with microkinetic modeling creates a powerful framework for predicting not only catalytic activity but also selectivity patterns under realistic reaction conditions.

Advanced Electronic Descriptors and Machine Learning Integration

Beyond d-Band Center: Additional Electronic Descriptors

While the d-band center provides remarkable predictive power, recent research has identified supplementary electronic descriptors that offer enhanced accuracy for specific applications:

- d-Band Width: The second moment of the d-band DOS provides information about bandwidth and coupling strength between metal atoms.

- Projected Crystal Orbital Hamilton Population (pCOHP): Enables direct quantification of bonding and antibonding interactions between specific atom pairs.

- Work Function: Particularly important for electrochemical systems where electron transfer plays a crucial role.

- Bader Charges: Quantify charge transfer in adsorption processes and alloy systems.

These advanced descriptors often provide complementary information to the d-band center, especially when dealing with complex reaction networks or multi-element catalyst systems. For example, the combination of d-band center and work function has successfully predicted trends in electrochemical CO₂ reduction across different transition metal surfaces.

Descriptor Selection and Model Optimization

The effectiveness of ML models in predicting catalytic properties depends critically on descriptor selection and feature engineering. The comprehensive study on Cu-based bimetallic alloys utilized 18 distinct features for both the main and guest metals, including period, group, atomic number, atomic radius, atomic mass, boiling point, melting point, electronegativity, heat of fusion, ionization energy, density, and surface energy [23].

For optimal model performance, researchers should consider:

- Feature Correlation Analysis: Identify and remove highly correlated descriptors to improve model stability.

- Domain Knowledge Integration: Prioritize features with established physical significance in catalytic processes.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Employ principal component analysis (PCA) or autoencoders for high-dimensional descriptor spaces.

- Model Interpretation: Utilize SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values to understand descriptor importance in predictions.

The implementation of ML algorithms for descriptor prediction typically utilizes open-source libraries such as Scikit-Learn [23]. For large datasets or complex architectures, deep learning frameworks like TensorFlow or PyTorch offer enhanced modeling capabilities, though with increased computational requirements.

Table 3: Computational Tools for Electronic Structure Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| VESTA | 3D visualization of structural models and volumetric data | Visualization of electron/nuclear densities, crystal morphologies, multiple format support | Free for non-commercial use [24] |

| Amsterdam Modeling Suite (AMS) | Atomistic and multiscale modeling | Fast electronic structure, ML potentials, reactivity prediction | Commercial with trial license [25] |

| Scikit-Learn | Machine learning library | Comprehensive ML algorithms, easy integration with Python workflows | Open source [23] |

| Dragon/AlvaDesc | Molecular descriptor calculation | 5000+ molecular descriptors, user-friendly interface | Commercial [26] |

| WIEN2k | Electronic structure calculations | Full-potential linearized augmented plane-wave (FP-LAPW) method | Academic licensing [24] |

Electronic structure descriptors, particularly the d-band center, provide an essential theoretical framework for understanding and predicting catalytic behavior. The integration of these fundamental descriptors with machine learning approaches has created powerful workflows for accelerated catalyst discovery, dramatically reducing the computational cost compared to traditional DFT screening methods [23].

Future advancements in this field will likely focus on several key areas: (1) development of more sophisticated descriptors that capture complex surface-adsorbate interactions with greater fidelity; (2) integration of temporal dynamics to describe catalyst evolution under operating conditions; (3) improved multi-scale modeling that connects electronic descriptors to reactor-scale performance; and (4) enhanced experimental validation through advanced characterization techniques that directly probe descriptor-activity relationships.

For researchers in catalysis and drug development, mastery of electronic descriptor concepts enables more targeted design of functional materials, whether for sustainable energy applications or pharmaceutical synthesis. The continued refinement of these theoretical frameworks, coupled with advances in computational power and machine learning algorithms, promises to further accelerate the discovery and optimization of next-generation catalytic materials.

The Role of Scaling Relationships and Their Limitations in Prediction

In computational catalysis, linear scaling relationships (LSRs) and Brønsted-Evans-Polanyi (BEP) relations have become fundamental tools for predicting catalytic activity and streamlining catalyst discovery. LSRs describe the linear correlations between the adsorption energies of different reaction intermediates on catalytic surfaces, while BEP relations connect activation energies to reaction thermodynamics [27] [28]. These relationships simplify the complex parameter space of catalyst design, enabling high-throughput computational screening by reducing the need for exhaustive density functional theory (DFT) calculations [28].

However, these scaling relations impose inherent thermodynamic limitations on catalytic performance, particularly for multi-step reactions where optimizing the binding strength of one intermediate often adversely affects others [29]. This review examines the fundamental role of scaling relationships in prediction, explores their limitations through quantitative error analysis, and presents emerging strategies to overcome these constraints through dynamic catalysis, machine learning, and advanced descriptor design—all within the broader context of improving predictive accuracy in descriptor-based catalytic research.

Fundamental Scaling Relationships in Catalysis

Theoretical Basis and Chemical Origins

Linear scaling relationships emerge from the fundamental principle that the bonding of different adsorbates to catalyst surfaces often involves similar chemical interactions. For instance, in the oxygen evolution reaction (OER), the adsorption energies of *OH, *O, and *OOH intermediates are linearly correlated because each additional oxygen atom in the sequence introduces similar bonding contributions [29]. These correlations arise because the number of metal-oxygen bonds changes predictably across different intermediates [28].

The universality of LSRs across different catalyst materials stems from the common bonding patterns between adsorbates and catalyst surfaces. On transition metal surfaces, the adsorption energy of an intermediate often correlates with the energy of the d-band center of the metal, leading to predictable relationships across different metal compositions [30]. Similarly, BEP relations originate from the observation that transition states often resemble either reactants or products along the reaction coordinate, creating linear dependencies between activation barriers and reaction energies [27].

Quantitative Formulations in Predictive Modeling

The mathematical formulation of LSRs typically follows the linear equation:

[ E{ads,B} = m \times E{ads,A} + c ]

Where (E{ads,A}) and (E{ads,B}) represent the adsorption energies of two different intermediates, (m) is the scaling slope, and (c) is the intercept. These parameters are typically derived from DFT calculations across a range of catalyst materials [28].

In microkinetic modeling (MKM), LSRs and BEP relations dramatically reduce computational cost. Instead of calculating all activation energies and adsorption energies individually, researchers can estimate these values from a limited set of DFT calculations, making complex reaction networks computationally tractable [28]. This approach has been successfully applied to numerous catalytic reactions, including CO₂ hydrogenation [27], oxygen evolution [29], and methane coupling [2].

Table 1: Common Scaling Relationships in Heterogeneous Catalysis

| Reaction | Scaling Relationship | Key Intermediates | Impact on Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Evolution Reaction (OER) | *OOH vs *OH | *OH, *O, *OOH | Limits theoretical overpotential to ~0.37V [29] |

| CO₂ Hydrogenation | Formate formation barriers vs thermodynamics | CO₂, H, HCOO | Constrains methanol synthesis activity [27] |

| Nitrate Reduction | Intermediate adsorption energies | NO₃, NO₂, NO* | Affects NH₃ selectivity prediction [31] |

Limitations and Prediction Errors in Scaling Relationships

Intrinsic Thermodynamic Limitations

The most significant limitation of LSRs is the thermodynamic ceiling they impose on catalytic performance. For OER, the scaling relationship between *OOH and *OH adsorption energies dictates a minimum theoretical overpotential of ~0.37 V, regardless of catalyst material [29]. This fundamental constraint emerges because strengthening *OOH binding to facilitate the O-O bond formation inevitably over-stabilizes *OH, making the O-H bond cleavage step more difficult [29].

Similar limitations affect CO₂ reduction, where scaling relationships between *COOH, *CO, and other intermediates restrict the theoretically achievable overpotentials and selectivities for desired products like methanol [30]. These intrinsic limitations create a "catalytic ceiling" that cannot be overcome by any single-site catalyst obeying conventional scaling relationships, regardless of how extensively researchers screen candidate materials [29].

Parametric Uncertainty and Error Propagation

The approximate nature of LSRs introduces significant uncertainty into predictive models. DFT calculations themselves contain inherent errors of approximately 0.2 eV or more compared to benchmark experimental measurements [28]. When these errors propagate through scaling relationships into microkinetic models, they can cause orders-of-magnitude uncertainty in predicted rates due to the exponential dependence of rates on activation barriers [28].

This parametric uncertainty affects not only activity predictions but also selectivity forecasts and the identification of optimal reaction pathways in complex networks [28]. For electrocatalytic reactions, DFT error can impart substantial uncertainty to volcano plot descriptors and associated activity predictions [28]. The problem is particularly acute in programmable catalysis, where the impact of parametric uncertainty on performance predictions remains largely unquantified [28].

Table 2: Sources of Error in Scaling Relationship-Based Predictions

| Error Source | Typical Magnitude | Impact on Predictions | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT Computational Error | ~0.2 eV or greater [28] | Orders-of-magnitude rate uncertainty [28] | Hybrid functionals, error estimation [28] |

| Scaling Relation Regression Error | ~0.1-0.3 eV [28] | Incorrect activity trends, pathway misidentification [28] | Multi-descriptor models, uncertainty quantification [31] |

| Data Incompleteness | Variable | Failure to identify optimal catalysts [2] | High-throughput screening, active learning [32] |

Strategies for Overcoming Scaling Relation Limitations

Dynamic and Programmable Catalysis

Dynamic structural regulation of active sites presents a promising approach to circumvent scaling relationships. In OER, a Ni-Fe molecular catalyst demonstrated that dynamic evolution of Ni-adsorbate coordination driven by intramolecular proton transfer can simultaneously lower the free energy changes associated with O-H bond cleavage and O-O bond formation [29]. This dynamic dual-site cooperation breaks the conventional scaling relationship by enabling independent optimization of typically correlated steps [29].

The emerging field of programmable catalysis utilizes controlled temporal modulation of catalyst properties to achieve performance enhancements beyond static scaling limits [28]. By oscillating catalyst parameters such as potential, strain, or coverage, programmable catalysts can access transition states and intermediate stabilizations that violate conventional scaling relationships [28]. However, parametric uncertainty remains a significant challenge for predicting optimal waveform parameters in these systems [28].

Multi-Functional and Inverse Catalysts

Inverse catalysts—metal oxide nanoparticles supported on metal surfaces—have demonstrated exceptional ability to break linear scaling relations. In CO₂ hydrogenation to methanol, In₂O₃/Cu(111) inverse catalysts exhibit formate formation energy barriers that deviate significantly from BEP relations due to highly asymmetric active sites at the metal-oxide interface [27]. The structural complexity of these systems, with numerous possible active sites of different sizes and stoichiometries, creates diverse local environments that enable simultaneous optimization of multiple reaction steps [27].

Similar principles apply to high-entropy alloys (HEAs), where the immense chemical complexity of surfaces composed of five or more elements creates unique active sites capable of stabilizing intermediates in ways that violate conventional scaling relationships derived from pure metal surfaces [32]. The coordination environments in HEAs extend far beyond simple monodentate adsorption motifs, requiring more sophisticated descriptors to capture their unique catalytic behavior [32].

Machine Learning and Advanced Descriptors

Machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) enable efficient exploration of complex catalytic systems beyond the limitations of traditional scaling relationships. For inverse catalysts, Gaussian moment neural network (GM-NN) potentials can rapidly screen thousands of active sites at near-DFT accuracy, identifying those that break conventional scaling relations [27]. This approach dramatically reduces the computational cost of searching asymmetric active site motifs where scaling relationships typically fail [27].

Equivariant graph neural networks (equivGNNs) enhance atomic structure representations to resolve chemical-motif similarity in complex catalytic systems, achieving mean absolute errors <0.09 eV for descriptor prediction across diverse interfaces [32]. These models overcome limitations of simpler representations that fail to distinguish between similar adsorption motifs with different catalytic properties [32].

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

High-Throughput Experimentation and Data Collection

Advanced reactor systems enable high-throughput catalyst testing under well-defined, process-consistent conditions. Modern screening instruments can automatically evaluate dozens of catalysts under hundreds of reaction conditions, generating datasets with thousands of data points essential for understanding complex parameter spaces [33]. These systems reduce data variability compared to conventional experimentation, providing higher-quality data for ML model training [30].

Proper reactor selection and design are critical for generating scalable kinetic data. Chemical engineering principles dictate that test reactors should maintain relevant criteria such as concentration and temperature gradients, flow patterns, and pressure drops that accurately reflect commercial operation conditions [33]. For structured catalysts, scaled-down versions can effectively simulate commercial units, while for particulate systems, criteria like the Carberry number and Weisz-Prater criterion ensure absence of mass transfer limitations [33].

Computational Workflows for Descriptor Validation

ML-driven transition state search workflows combine the efficiency of machine learning potentials with the accuracy of DFT validation. For inverse catalyst systems, researchers first train neural network potentials on diverse cluster structures, then use these potentials to rapidly identify transition state guesses across numerous active sites [27]. Promising candidates are subsequently refined using higher-level DFT calculations with improved basis sets and k-point sampling [27].

Interpretable machine learning techniques like Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) enable quantitative analysis of feature importance in complex catalyst datasets. For single-atom catalysts in nitrate reduction, SHAP analysis identified that favorable activity stems from a balance between three critical factors: low number of valence electrons, moderate nitrogen doping concentration, and specific doping patterns [31]. This approach facilitates descriptor development that integrates intrinsic catalytic properties with structural features like intermediate bond angles [31].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Scaling Relationship Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Inverse Catalyst Systems (e.g., In₂O₃/Cu(111)) | Breaking scaling relations via interface sites [27] | Cluster size, stoichiometry, metal-support interactions |

| Single-Atom Catalysts (e.g., TM on BC₃) | Isolating active sites for fundamental studies [31] | Metal-center properties, coordination environment, stability |

| Dynamic Catalysts (e.g., Ni-Fe complexes) | Circumventing scaling via structural dynamics [29] | In situ activation, operando characterization, stability |

| High-Entropy Alloys | Creating unique sites beyond simple scaling [32] | Composition complexity, surface disorder, characterization |

The field of scaling relationship research is rapidly evolving beyond simple linear correlations toward multidimensional descriptor spaces that better capture the complexity of catalytic interfaces. The integration of computational and experimental ML models through suitable intermediate descriptors represents a promising research paradigm [30]. Spectral descriptors and operando characterization data provide additional dimensions for understanding catalyst behavior beyond traditional adsorption energy correlations [30].

Uncertainty-aware microkinetic modeling will play an increasingly important role in robust catalyst prediction. Monte Carlo frameworks that sample model input parameters from uncertainty distributions can quantify the reliability of performance predictions and identify parameters that require more accurate determination [28]. This approach is particularly valuable for emerging fields like programmable catalysis, where the impact of parametric uncertainty on optimal design parameters remains poorly understood [28].

In conclusion, while linear scaling relationships provide valuable simplifying principles for catalyst prediction, their limitations necessitate more sophisticated approaches that account for structural dynamics, multi-site cooperation, and complex local environments. The integration of machine learning, high-throughput experimentation, and advanced theoretical methods enables researchers to move beyond the constraints of simple scaling relationships toward more accurate prediction of catalytic activity and selectivity. Future advances will likely focus on developing dynamic, multi-functional catalyst systems whose performance is not bounded by traditional scaling limitations, ultimately enabling more efficient and sustainable chemical processes.

Descriptor Toolkits: Methods and Real-World Applications in Prediction

Constructing Computational Descriptors from Density Functional Theory (DFT)

In the pursuit of sustainable energy and efficient chemical production, the design of high-performance catalysts is a paramount research area for both experimentalists and theorists. Computational catalysis, particularly through descriptor-based approaches, has emerged as a powerful strategy for identifying promising catalyst candidates for essential reactions. Descriptors are quantifiable properties—derived from theory, calculation, or experiment—that serve as proxies for catalytic performance, enabling researchers to bypass expensive and time-consuming experimental screening. Within this paradigm, Density Functional Theory (DFT) has become the computational workhorse for obtaining accurate descriptor values, as it provides a balance between computational efficiency and quantum mechanical accuracy for predicting the electronic and structural properties of molecules and materials.

The fundamental thesis underpinning this guide is that catalytic activity and selectivity can be predicted through computational descriptors derived from the electronic structure and geometric environment of catalytic systems. By establishing quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSARs), descriptors act as a crucial link between a catalyst's inherent properties and its performance, thereby accelerating the rational design of new catalytic materials. This guide provides an in-depth technical framework for constructing such descriptors from DFT, detailing the core theoretical principles, practical classification, and advanced integration with machine learning (ML) that is reshaping modern computational catalysis.

DFT: The Theoretical Foundation for Descriptor Calculation

Core Principles of DFT