High-Throughput Screening for Catalyst Discovery: Integrating Computational and Experimental Methods

This article provides a comprehensive overview of high-throughput screening (HTS) methodologies accelerating catalyst discovery.

High-Throughput Screening for Catalyst Discovery: Integrating Computational and Experimental Methods

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of high-throughput screening (HTS) methodologies accelerating catalyst discovery. It explores the foundational shift from traditional trial-and-error approaches to integrated computational and experimental paradigms, detailing specific applications of density functional theory, machine learning, and automated experimental setups. The content addresses critical challenges in data quality, assay validation, and hit identification, while presenting a comparative analysis of screening strategies. Aimed at researchers and development professionals, this review synthesizes current advancements and future directions for developing cost-competitive, high-performance catalytic materials for energy and chemical applications.

The Paradigm Shift in Catalyst Discovery: From Trial-and-Error to High-Throughput Methodologies

Catalysis, the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction without itself being consumed, is fundamental to the chemical industry, with an estimated 90% of all commercially produced chemical products involving catalysts at some stage of their manufacture [1]. The systematic study of catalysis began in the 1700s, with Elizabeth Fulhame providing its theoretical foundation and Jöns Jakob Berzelius coining the term "catalysis" in 1835 [2] [1]. Research methodologies have evolved through three distinct stages: from early empirical discovery, through a computational and high-throughput screening phase, to the emerging paradigm of autonomous and data-driven research. This evolution has been driven by the need to develop more efficient, selective, and sustainable chemical processes, particularly those supporting renewable energy and environmental goals [2] [3]. Within this context, high-throughput screening methods have become indispensable for accelerating the discovery and optimization of novel catalysts, enabling researchers to efficiently navigate the vast multi-dimensional space of possible catalytic materials [4].

The Empirical Foundations Stage (1700s–Late 20th Century)

The first stage of catalysis research was characterized by experimental observation and serendipitous discovery. Researchers identified catalytic materials through trial-and-error experimentation, with theoretical understanding lagging behind practical application.

Key Methodological Approaches

The empirical stage relied heavily on observation of natural processes and laboratory experimentation with systematic variation of reaction conditions. Paul Sabatier's work in the late 19th and early 20th centuries exemplified this approach, leading to the discovery of many metal catalysts, particularly nickel and platinum group metals, through meticulous experimentation [2]. This period also saw the development of bulk characterization techniques such as X-ray diffraction and basic spectroscopy, which provided limited insights into catalyst structure.

Classic Experimental Protocols

A representative experimental protocol from this era involved the systematic testing of catalyst formulations:

- Catalyst Preparation: Materials were prepared using standard synthesis methods like precipitation, impregnation, or fusion. For example, heterogeneous catalysts for the Haber process were described as iron but were actually complex mixtures of iron-potassium-calcium-aluminum-oxide [1].

- Reactor Testing: Catalysts were tested in fixed-bed or batch reactors under varying conditions of temperature, pressure, and reactant concentrations.

- Product Analysis: Researchers used techniques like gas chromatography, titration, or spectroscopy to quantify reaction products and calculate conversion and selectivity.

- Kinetic Modeling: Reaction rates were measured and fitted to kinetic models to understand reaction mechanisms.

Table 1: Landmark Empirical Discoveries in Catalysis

| Time Period | Catalyst Discovery | Methodological Approach | Industrial Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Late 1700s | Acids for ester hydrolysis | Systematic solution chemistry | Various chemical processes |

| Early 1900s | Nickel catalysts | Gas-solid reaction testing | Hydrogenation reactions |

| Early 1900s | Vanadium(V) oxide | Oxide screening | Contact process (SO₂ to SO₃) |

| Mid-1900s | Zeolites | Crystal structure analysis | Petroleum refining |

Limitations and Legacy

The empirical approach suffered from several limitations: the high cost and slow pace of experimentation, limited fundamental understanding of reaction mechanisms, and the inability to predict catalyst performance from first principles. Despite these constraints, this era established foundational catalytic processes still in use today, including the Haber process for ammonia synthesis and the contact process for sulfuric acid production [5] [1]. The phenomenological "Seven Pillars" of oxidation catalysis proposed by Robert K. Grasselli—encompassing lattice oxygen, metal-oxygen bond strength, host structure, redox properties, multifunctionality of active sites, site isolation, and phase cooperation—represented a high point of empirical knowledge, summarizing the essential features for designing metal oxides for selective hydrocarbon oxidation [6].

The Computational and High-Throughput Screening Stage (Late 20th Century–Present)

The second stage of catalysis research emerged with advances in computational power and the adoption of parallel experimentation techniques. This paradigm shift enabled researchers to move beyond trial-and-error approaches toward more rational catalyst design.

Methodological Advances

The computational screening stage introduced several transformative approaches:

- First-Principles Calculations: Density functional theory (DFT) allowed researchers to predict catalytic properties by calculating electronic structures, adsorption energies, and reaction pathways [4] [6].

- Descriptor-Based Screening: Electronic structure descriptors such as the d-band center and related parameters enabled the prediction of catalytic activity and selectivity trends [4] [6].

- High-Throughput Experimentation: Automated synthesis and testing platforms enabled the parallel preparation and evaluation of hundreds to thousands of catalyst candidates [4].

High-Throughput Screening Protocol for Bimetallic Catalysts

A representative high-throughput protocol for discovering bimetallic catalysts involves the following steps [4]:

Computational Prescreening

- Define reference material (e.g., Pd for H₂O₂ synthesis)

- Generate candidate structures (4,350 bimetallic alloys in demonstrated study)

- Calculate formation energies (ΔEf) to assess thermodynamic stability

- Filter candidates with ΔEf < 0.1 eV/atom

Electronic Structure Analysis

- Calculate density of states (DOS) patterns for stable candidates

- Quantify similarity to reference catalyst using ΔDOS metric: where g(E;σ) is a Gaussian weighting function centered at the Fermi energy

- Select top candidates with lowest ΔDOS values

Experimental Validation

- Synthesize screened candidates (e.g., via impregnation, co-precipitation)

- Evaluate catalytic performance (e.g., H₂O₂ synthesis from H₂ and O₂)

- Measure activity, selectivity, and stability under working conditions

- Compare with reference catalyst and computational predictions

This protocol successfully identified several promising Pd-free catalysts, including Ni₆₁Pt₃₉, which exhibited a 9.5-fold enhancement in cost-normalized productivity compared to conventional Pd catalysts [4].

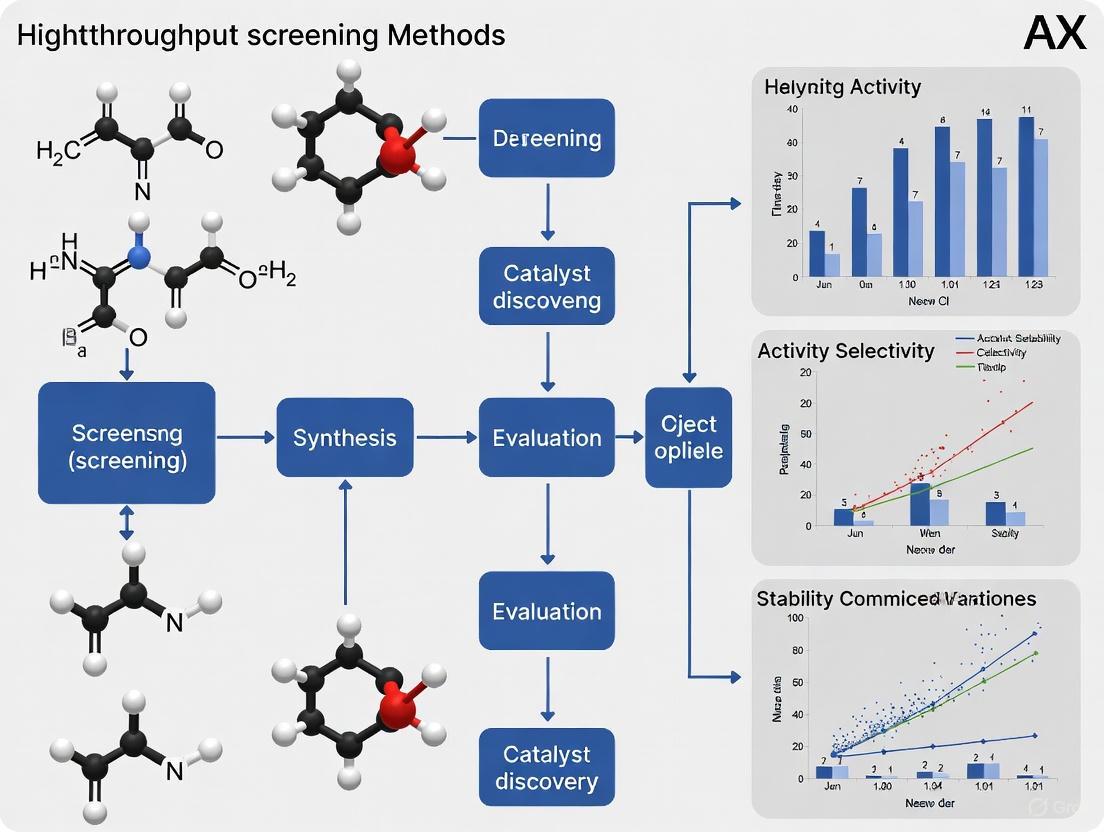

Diagram 1: High-throughput screening workflow for bimetallic catalyst discovery. The protocol combines computational screening with experimental validation to identify promising catalysts efficiently [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for High-Throughput Catalyst Screening

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Precursors (Salts, Complexes) | Active phase components | Ni, Pt, Pd, Au salts for bimetallic catalysts [4] |

| Support Materials (Alumina, Zeolites, Carbon) | High-surface-area carriers | Catalyst dispersion and stabilization [1] |

| DFT Simulation Software | Electronic structure calculation | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO for property prediction [4] |

| High-Throughput Reactor Systems | Parallel reaction testing | Simultaneous evaluation of multiple catalysts [4] [7] |

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 3: Experimental Results for Screened Bimetallic Catalysts [4]

| Catalyst Composition | DOS Similarity (ΔDOS) | Catalytic Performance | Cost-Normalized Productivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pd (Reference) | 0 (Reference) | Baseline | 1.0 (Reference) |

| Ni₆₁Pt₃₉ | 1.72 | Comparable to Pd | 9.5 × Pd |

| Au₅₁Pd₄₉ | 1.45 | Comparable to Pd | Not specified |

| Pt₅₂Pd₄₈ | 1.52 | Comparable to Pd | Not specified |

| Pd₅₂Ni₄₈ | 1.63 | Comparable to Pd | Not specified |

| FeCo (B2) | 1.63 | Not validated | Not validated |

| CrRh (B2) | 1.97 | Not validated | Not validated |

The Autonomous and Data-Driven Stage (Emerging Paradigm)

The emerging third stage of catalysis research integrates artificial intelligence, autonomous laboratories, and standardized data frameworks to create self-optimizing catalyst discovery systems.

Methodological Innovations

The autonomous research paradigm introduces several groundbreaking approaches:

- Machine Learning and AI: Advanced algorithms identify complex patterns in high-dimensional data, enabling predictive models for catalyst design without complete mechanistic understanding [7] [6].

- Autonomous Laboratories: Robotic systems coupled with AI-driven decision-making can plan, execute, and analyze experiments with minimal human intervention [7].

- Standardized Data Handbooks: Community-wide adoption of standardized measurement protocols and data reporting ensures high-quality, reusable datasets for AI training [6].

Autonomous Workflow Protocol

An autonomous catalyst discovery workflow integrates multiple advanced methodologies:

Hypothesis Generation

- AI analysis of existing literature and experimental data

- Identification of promising compositional and structural spaces

- Prediction of novel catalyst candidates with desired properties

Autonomous Computation

- Robotic DFT calculations to screen candidate materials

- Reinforcement learning to optimize calculation strategies

- Automatic detection of promising candidates for experimental validation

Autonomous Experimentation

- Robotic synthesis of predicted catalysts

- High-throughput testing under realistic conditions

- Real-time adaptive optimization based on incoming data

Closed-Loop Learning

- Experimental results fed back to improve computational models

- Continuous refinement of prediction accuracy

- Expansion of chemical space exploration based on accumulated knowledge

This integrated approach significantly reduces the human cost and time required for catalyst development while potentially discovering non-intuitive catalyst formulations that might be overlooked by human researchers [7].

Diagram 2: Autonomous catalysis research cycle. This closed-loop system integrates AI, automated computations, and robotic laboratories to accelerate catalyst discovery [7].

Experimental Handbook Framework

The implementation of autonomous research requires standardized data collection protocols. A proposed handbook framework for catalytic oxidation includes [6]:

- Minimum Reporting Standards: Compulsory documentation of catalyst history, pretreatment conditions, and structural evolution during operation.

- Reference Materials: Inclusion of benchmark catalysts in all experimental series to enable cross-laboratory data comparison.

- Stability Testing Protocols: Standardized procedures for assessing catalyst deactivation and regeneration.

- Data Formats: Uniform data templates ensuring compatibility with AI and machine learning algorithms.

Research Reagent Solutions for Autonomous Discovery

Table 4: Essential Tools and Reagents for Autonomous Catalysis Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Robotic Synthesis Platforms | Automated catalyst preparation | Liquid handling, impregnation, calcination robots [7] |

| AI/ML Software Suites | Predictive model development | TensorFlow, PyTorch with chemical informatics extensions [7] [6] |

| Standardized Catalyst Libraries | Reference materials and benchmarks | Certified oxide supports, metal precursors [6] |

| In Situ/Operando Characterization | Real-time monitoring of catalyst structure | XRD, XPS, spectroscopy during reaction [6] |

The evolution of catalysis research from empirical observations to computational screening and now toward autonomous discovery represents a fundamental transformation in methodological approaches. High-throughput screening serves as the critical bridge between the first and third stages of this evolution, enabling the rapid assessment of catalyst candidates predicted by computational methods. The emerging paradigm of autonomous catalysis research promises to significantly accelerate the discovery of novel catalysts for essential applications such as renewable energy conversion, carbon dioxide utilization, and sustainable chemical synthesis [2] [3] [7]. As these methodologies mature and become more widely adopted, they will likely transform catalyst development from a largely empirical art to a predictive science, ultimately supporting the transition to a more sustainable chemical industry.

Core Principles of High-Throughput Screening in Materials Science

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) is an indispensable technology that has transformed discovery processes across multiple scientific disciplines. In materials science, it enables the rapid testing of thousands to millions of material compositions, structures, or processing conditions to identify candidates with desirable properties. This approach is particularly valuable in catalyst discovery research, where it greatly speeds up the progress of identifying and optimizing new catalytic materials by systematically exploring vast parameter spaces that would be impractical to investigate through traditional one-at-a-time experimentation. The core principle involves using automation, miniaturized assays, and parallel processing to accelerate the discovery and optimization of functional materials, significantly reducing time, reagent consumption, and labor expenses compared to conventional methods [8].

The global HTS market, valued at approximately $18.8 billion for 2025-2029, reflects its critical role in industrial and academic research, with significant applications in pharmaceutical development, materials science, and catalyst discovery. Market analysis indicates that HTS can reduce development timelines by approximately 30% and improve forecast accuracy by up to 18% in materials science applications, demonstrating its transformative impact on research efficiency [9].

Core Principles and Quantitative Foundations

The implementation of HTS in materials science is governed by several interconnected principles that ensure efficient, reliable, and meaningful results. These principles encompass experimental design, data acquisition, and analysis methodologies specifically adapted for the unique challenges of material systems.

Digital Barcoding for Sample Multiplexing

A fundamental principle of modern HTS is the use of digital barcodes to label individual samples, enabling simultaneous processing and analysis of thousands of unique specimens. This multiplexing capability is the cornerstone of achieving high throughput. Four primary barcoding technologies have been successfully adapted for materials research, each with distinct characteristics and detection methodologies [8].

Table 1: Digital Barcoding Technologies for HTS in Materials Science

| Barcode Type | Encoded Information | Detection Method | Applications in Materials Science | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Barcode [8] | Presence/Absence of fluorescent dyes (1 bit/dye) | Flow Cytometry, Fluorescence Microscopy | Analysis of material-cell interactions, screening of functionalized nanoparticles | High detection speed, compatible with live-cell assays |

| DNA Barcode [8] | Nucleotide sequences (2 bits/nucleotide) | Second-Generation DNA Sequencing | Screening of drug delivery vehicles (e.g., lipid nanoparticles, polymers), catalyst libraries | Extremely high multiplexing capacity (4N codes for N nucleotides) |

| Heavy Metal Barcode [8] | Isotopes of rare earth and transition metals | Mass Cytometry | High-dimensional analysis of material properties and effects | Minimal signal overlap, enables detection of >40 simultaneous labels |

| Nonmetal Isotope Barcode [8] | Stable isotopes (e.g., 13C, 15N) | Secondary-Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS) | Mapping material composition and chemical activity at high resolution | Enables highly multiplexed spatial imaging |

Quantitative Data Analysis and Curve Fitting

In quantitative HTS (qHTS), materials are tested across a range of concentrations or conditions, generating concentration-response relationships that are fitted to mathematical models to extract key parameters. The Hill equation (HEQN) is a widely used model for sigmoidal response data, though its application requires careful statistical consideration [10].

The logistic form of the Hill equation is:

( Ri = E0 + \frac{(E\infty - E0)}{1 + \exp{-h[\log Ci - \log AC{50}]}} )

Where:

- ( Ri ) is the measured response at concentration ( Ci )

- ( E_0 ) is the baseline response

- ( E_\infty ) is the maximal response

- ( AC_{50} ) is the concentration for half-maximal response (potency)

- ( h ) is the Hill slope (shape parameter)

The parameter estimates, particularly ( AC_{50} ), are highly sensitive to experimental design. Estimates are precise only when the tested concentration range defines both upper and lower asymptotes of the curve. Failure to capture these asymptotes can lead to confidence intervals spanning several orders of magnitude, greatly hindering reliable material ranking and selection [10].

Table 2: Impact of Experimental Design on Parameter Estimation Reliability

| True AC50 (μM) | True Emax (%) | Sample Size (n) | Mean & [95% CI] for AC50 Estimates | Implications for Materials Screening |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.001 [10] | 25 [10] | 1 [10] | 7.92e-05 [4.26e-13, 1.47e+04] [10] | Highly unreliable for ranking material potency |

| 0.001 [10] | 50 [10] | 5 [10] | 2.91e-04 [5.84e-07, 0.15] [10] | Improved but still variable for low-efficacy materials |

| 0.1 [10] | 50 [10] | 3 [10] | 0.10 [0.06, 0.16] [10] | Reliable estimation when asymptotes are defined |

| 0.1 [10] | 50 [10] | 5 [10] | 0.10 [0.05, 0.20] [10] | Excellent precision for high-confidence decisions |

Artifact Identification and Data Quality Control

HTS data, particularly in complex material systems, are susceptible to various artifacts that can compromise data quality. A robust HTS pipeline must incorporate protocols to identify and flag these artifacts. Major confounding factors include autofluorescence of materials and cytotoxic effects in cell-based assays. On average, cytotoxicity affects approximately 8% of compounds in screening libraries, while autofluorescence affects less than 0.5% [11].

Advanced data analysis pipelines adopt metrics like the weighted Area Under the Curve (wAUC) to quantify total activity across the tested concentration range. This metric has demonstrated superior reproducibility (Pearson’s r = 0.91) compared to point estimates like AC50 (r = 0.81) or point-of-departure (POD) concentration (r = 0.82), making it particularly valuable for robust material prioritization [11].

Experimental Protocols for HTS in Catalyst Discovery

The following protocol provides a framework for applying HTS principles to catalyst discovery research, incorporating best practices from established screening methodologies.

Protocol: High-Throughput Screening of Heterogeneous Catalyst Libraries

Objective: To rapidly identify and optimize solid-state catalyst materials for a target chemical reaction from a diverse library of compositions.

Principle: A library of catalyst candidates is synthesized in a miniaturized format (e.g., 96- or 384-well microplates). Each catalyst is evaluated in parallel using a high-throughput reactor system coupled to a rapid detection method (e.g., mass spectrometry, gas chromatography). Catalytic performance (e.g., conversion, selectivity) is measured and analyzed to select lead candidates for further validation [12] [9].

Step 1: Library Design and Miniaturized Synthesis

- Library Design: Define the compositional space to be explored (e.g., mixed metal oxides, supported metals). Use design of experiments (DoE) software to maximize coverage of the parameter space with a minimal number of discrete compositions.

- Substrate Preparation: Use functionalized wafer substrates or pre-fabricated microplates suitable for high-temperature reactions.

- Automated Synthesis: Employ robotic liquid handlers and inkjet printers to deposit precursor solutions in a combinatorial fashion onto the substrate.

- Reagent Solutions: Metal salt precursors (e.g., nitrates, chlorides), solvent (e.g., water, ethanol), stabilizing agents (e.g., polymers).

- Calcination: Programmable furnace to convert precursors to final catalytic materials (e.g., 400-800°C for 2-8 hours in air).

Step 2: High-Throughput Activity Screening

- Reactor System: Load the catalyst library into a parallel microreactor system where each catalyst spot is addressed individually or as part of a larger array.

- Reaction Conditions: Introduce reactant gases (e.g., CO + O₂ for oxidation, H₂ for hydrogenation) at controlled flow rates, temperatures (200-500°C), and pressures using mass flow controllers.

- Product Detection: Use a rapid-sampling mass spectrometer or a multiplexed gas chromatograph system to analyze effluent from each microreactor in sequence.

- Key Parameter: Measure conversion of key reactant and selectivity to desired product.

Step 3: Data Acquisition and Primary Analysis

- Data Collection: Automate the collection of raw analytical data (e.g., mass spectra, chromatographic peaks) and link them to specific catalyst compositions via a barcoding or positional mapping system [8].

- Data Processing: Convert raw signals into quantitative performance metrics (e.g., % conversion, % selectivity, turnover frequency).

- Quality Control: Apply noise-filtering and curation protocols to flag and exclude data from faulty reactors or contaminated samples [11]. Calculate the Z'-factor for the entire plate to assess assay quality.

- Formula: ( Z' = 1 - \frac{3(\sigmap + \sigman)}{|\mup - \mun|} ), where ( \sigma ) is standard deviation and ( \mu ) is mean of positive (p) and negative (n) controls. An assay with Z' > 0.5 is considered excellent.

Step 4: Hit Identification and Concentration-Response Analysis

- Primary Hit Selection: Rank catalysts based on primary performance metrics (e.g., top 10% by conversion or selectivity).

- Dose-Response Profiling: For selected hits, synthesize and test a series of concentrations or loadings of the active component to establish a concentration-activity relationship.

- Curve Fitting: Fit the activity data to a suitable model (e.g., Hill equation) to extract parameters like AC50 (concentration for half-maximal activity) and Emax (maximal efficacy) [10]. Use the weighted Area Under the Curve (wAUC) as a robust metric for overall performance [11].

- Lead Selection: Prioritize catalysts based on a combination of high efficacy (Emax), high potency (low AC50), and favorable wAUC.

Workflow Visualization and Data Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for a high-throughput screening campaign in catalyst discovery, from library preparation to lead candidate identification.

HTS Workflow for Catalyst Discovery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of HTS requires a suite of specialized reagents, materials, and instrumentation. The following table details key solutions essential for establishing a robust HTS pipeline in materials science.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HTS in Materials Science

| Category | Specific Reagent/Material | Function in HTS Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Library Synthesis [8] | Metal Salt Precursors (e.g., Nitrates, Chlorides) | Raw materials for combinatorial synthesis of catalyst libraries. |

| Library Synthesis [12] | Solvent Inks (Water, Ethanol, DMSO) | Vehicles for precise deposition of precursors via inkjet printing or robotic dispensing. |

| Barcoding [8] | Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., Alexa Fluor, Cy series) | Optical labels for tracking material samples or measuring reactions in cell-based assays. |

| Barcoding [8] | DNA Barcode Sequences | Unique molecular identifiers for ultra-high multiplexing of samples, decoded via sequencing. |

| Barcoding [8] | Heavy Metal Isotope Tags (Lanthanides) | Labels for mass cytometry-based detection, enabling high-plex, low-background screening. |

| Assay & Detection [9] | Microplates (96, 384, 1536-well) | Miniaturized platforms for parallel sample processing and analysis. |

| Assay & Detection [9] | Positive Control Compounds | Reference materials for assay validation and normalization of results across plates/runs. |

| Assay & Detection [10] | Detection Reagents (e.g., Luminescent Probes) | Reporters of catalytic activity or material property in a miniaturized format. |

| Data Analysis [11] | wAUC (Weighted Area Under Curve) | A robust quantitative metric for total activity, offering high reproducibility for ranking. |

The urgent need for sustainable energy technologies has placed electrochemical materials discovery at the forefront of scientific research. The traditional iterative approach to material investigation—preparing, testing, and analyzing samples sequentially—is often prohibitively time-consuming, especially given the nearly infinite permutations of potential materials of interest [13]. In response, high-throughput screening (HTS) methodologies have emerged as a powerful alternative, enabling the simultaneous testing of numerous samples in a single experimental setup [13].

Recent analyses reveal a significant paradigm shift: the field is now dominated by computational methods over experimental approaches. A comprehensive review of literature in this domain indicates that over 80% of published studies utilize computational techniques, primarily density functional theory (DFT) and machine learning (ML), with only a minority employing integrated computational-experimental workflows [14]. This review provides a detailed examination of this computational dominance, presenting quantitative analyses, experimental protocols, and visualization tools to guide researchers in leveraging these powerful approaches for accelerated materials discovery, particularly in the context of electrocatalyst development.

Quantitative Analysis of Methodological Distribution

Extensive analysis of current literature reveals distinct patterns in methodological approaches and research focus areas within high-throughput electrochemical materials discovery. The table below summarizes the quantitative distribution of these methodologies and their application areas based on recent publications.

Table 1: Distribution of Research Methodologies in Electrochemical Materials Discovery

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Approximate Prevalence (%) | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Screening | Density Functional Theory (DFT), Machine Learning (ML) | >80% [14] | Catalyst activity prediction, Stability assessment, Electronic structure analysis |

| Integrated Approaches | Automated setups combining computation & experiment [14] | <20% [14] | Closed-loop material discovery, Experimental validation |

| Experimental HTS | Scanning Electrochemical Microscopy (SECM), Scanning Droplet Cell (SDC) [13] | Minority of studies [14] | Direct performance measurement, Combinatorial library screening |

The research focus is heavily skewed toward certain material classes, creating significant gaps in understanding for other critical components:

Table 2: Research Focus Distribution by Material Type

| Material Type | Research Attention | Key Gaps Identified |

|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Materials | Dominant focus [14] | - |

| Ionomers/Membranes | Significant shortage [14] | Limited HTS studies on conductivity, stability |

| Electrolytes | Significant shortage [14] | Limited HTS studies on electrochemical windows, compatibility |

| Substrate Materials | Significant shortage [14] | Limited HTS studies on support effects, stability |

Furthermore, a critical analysis of screening criteria reveals that most current methodologies overlook crucial economic and safety factors, with fewer studies considering cost, availability, and safety—properties essential for assessing real-world economic feasibility [14].

Computational Methodologies and Protocols

Density Functional Theory (DFT) for Electrocatalysis

Protocol: DFT for Water Splitting Catalyst Evaluation

DFT has become indispensable for rationally designing electrocatalysts by providing atomic-level insights into reaction mechanisms and electronic structures [15]. The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for evaluating water-splitting catalysts (HER and OER):

System Setup

- Model Construction: Build a representative surface model of the catalyst (e.g., slab model for surfaces, cluster for nanoparticles).

- Software Selection: Choose a DFT code (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) with appropriate pseudopotentials and a plane-wave basis set.

- Functional Selection: Select an exchange-correlation functional (e.g., PBE for efficiency, RPBE for improved adsorption energies, HSE06 for hybrid accuracy).

Free Energy Calculation

- Utilize the Computational Hydrogen Electrode (CHE) model to calculate Gibbs free energy changes (ΔG) for reaction intermediates [15].

- Calculate the adsorption energy (ΔEH*) for hydrogen according to your system.

- Apply corrections for Zero-Point Energy (ΔZPE) and entropic effects (TΔS) to determine the final Gibbs free energy of adsorption (ΔGH*) [15]:

ΔG*H* = ΔE*H* + ΔZPE - TΔS

Activity Assessment

- Construct free energy diagrams for both HER and OER at U = 0 V vs. SHE.

- Identify the potential-determining step (PDS) as the step with the largest positive ΔG.

- The theoretical overpotential (η) can be derived from the free energy of the PDS.

This DFT-driven approach not only predicts activities of unsynthesized candidates but also elucidates the origins of observed catalyst performance, bridging the gap between experimental results and theoretical understanding [15].

Machine Learning Integration

Protocol: ML-Accelerated Material Screening

Machine learning models, particularly foundation models, are revolutionizing property prediction by leveraging transferable core components trained on broad data [16]. The following protocol describes their application:

Data Collection and Representation

- Data Sourcing: Extract and curate large-scale data from chemical databases (e.g., PubChem, ZINC, ChEMBL) or scientific literature using automated tools [16].

- Feature Representation: Convert molecular structures into machine-readable formats (e.g., SMILES, SELFIES) or crystal graphs for inorganic solids [16].

Model Selection and Training

- Encoder-Based Models (e.g., BERT architecture): Ideal for property prediction tasks [16].

- Decoder-Based Models (e.g., GPT architecture): Suitable for generative tasks like novel molecular design [16].

- Training Approach: Utilize pre-trained foundation models and fine-tune on specific, smaller datasets for downstream tasks [16].

Validation and Prediction

- Employ cross-validation techniques to assess model performance.

- Use SHAP or similar analysis for model interpretability.

- Integrate predictions with DFT for final validation in a closed-loop discovery pipeline.

This workflow is highly effective for populating large materials databases and enabling inverse design, where desired properties are used to generate candidate structures [16].

Experimental Validation Protocols

High-Throughput Electrochemical Screening

Protocol: Electrochemical HTS for Catalyst Libraries

While computational screening prioritizes candidates, experimental validation remains essential. High-throughput electrochemical screening allows rapid characterization of combinatorial material libraries [13].

Instrumentation Setup

- Core Equipment: Utilize a multichannel potentiostat capable of simultaneous measurements across multiple electrode positions [13].

- Electrode Configuration: Employ a multielectrode array or a scanning droplet cell (SDC) system [13].

- Cell Design: Implement a well-designed electrochemical cell compatible with your sample library format, ensuring minimal cross-talk between channels.

Library Fabrication

- Sample Deposition: Use automated deposition techniques (e.g., inkjet printing, sputtering) to create compositional gradients or discrete sample spots on a conductive substrate.

- Library Design: Plan the library to efficiently explore the compositional space of interest, often guided by prior computational predictions.

Electrochemical Characterization

- Technique Selection: Perform cyclic voltammetry (CV) or linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) across the array to assess activity.

- Data Acquisition: Run automated experiments controlled by software (e.g., using EC-Lab Developer Package) to collect current-voltage data for each library member [13].

- Data Analysis: Automate data processing to extract key metrics (e.g., onset potential, overpotential, current density, Tafel slope) for each sample.

Case Study: Quantitative Voltammetric Analysis

Protocol: Parameter Extraction for Multi-Electron Catalysts

For detailed mechanistic studies, a rigorous quantitative analysis of voltammetric data is essential. This protocol is adapted from studies on multi-redox molecular electrocatalysts [17] and paracetamol [18].

Experimental Conditions

- System: Three-electrode cell (Glassy Carbon working electrode, Pt counter electrode, SCE reference electrode).

- Solution: 1 × 10⁻⁶ M electroactive species (e.g., Paracetamol) with 0.1 M LiClO₄ as supporting electrolyte [18].

- Technique: Cyclic voltammetry at scan rates from 0.025 V/s to 0.300 V/s [18].

Data Analysis Workflow

- Determine Nature of Reaction: Assess peak separation (ΔEp) change with scan rate. An increase indicates quasi-reversible electron transfer [18].

- Calculate Transfer Coefficient (α): Use the Ep − Ep/2 method for reliable results [18].

- Calculate Diffusion Coefficient (D₀): Apply the modified Randles–Ševčík equation, which correlates peak current (Ip) with the square root of scan rate (ν¹ᐟ²) [18].

- Determine Heterogeneous Rate Constant (k₀): Use Kochi and Gileadi methods or a plot of ν⁻¹ᐟ² versus Ψ (from the Nicholson and Shain equation) for quasi-reversible systems [18].

Visualization of Workflows

Computational-Experimental Discovery Pipeline

The following diagram illustrates the integrated high-throughput computational and experimental workflow for accelerated materials discovery, highlighting the dominant role of computational methods.

High-Throughput Screening Classification

This diagram outlines the decision process for selecting the appropriate screening methodology based on research objectives and resources.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of high-throughput electrochemical discovery requires specific instrumentation and computational tools. The following table details key solutions and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for High-Throughput Discovery

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Software | DFT Codes (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) | Atomic-level calculation of electronic structure, binding energies, and reaction pathways [15]. |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Chemical Foundation Models (BERT, GPT architectures) | Pre-trained models for property prediction and molecular generation [16]. |

| Electrochemical Instrumentation | Multichannel Potentiostat (e.g., BioLogic) | Simultaneous electrochemical measurement across multiple samples in an array [13]. |

| Scanning Probe Workstations | Scanning Electrochemical Microscope (SECM) | Localized electrochemical measurements on combinatorial libraries with high spatial resolution [13]. |

| Data Extraction & Curation | Named Entity Recognition (NER) Tools | Automated extraction of materials data from scientific literature and patents [16]. |

| Reference Electrodes | Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) | Providing a stable, known reference potential in three-electrode experimental setups [18]. |

| Supporting Electrolytes | LiClO₄, KCl, etc. | Conducting current without participating in the electrochemical reaction, minimizing IR drop [18]. |

Application Note: Mapping the Landscape in High-Throughput Catalyst Discovery

High-throughput screening methods are revolutionizing catalyst discovery by accelerating the identification of novel materials. However, significant research gaps persist in both the categories of materials being investigated and the global distribution of research efforts. This application note details these gaps and provides validated experimental protocols to address them, enabling researchers to systematically explore underrepresented areas and foster more inclusive international collaboration.

Table 1: Underrepresented Material Classes in High-Throughput Electrochemical Research [14]

| Material Class | Research Focus Level | Key Unexplored Properties | Potential Impact Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionomers & Membranes | Shortage | Cost, Availability, Safety | Fuel Cells, Electrolysis |

| Electrolytes | Shortage | Durability, Safety | Batteries, Energy Storage |

| Substrate Materials | Shortage | Conductivity, Stability | All Electrochemical Systems |

| Non-Catalytic Materials | Shortage | Multi-property Optimization | System Integration |

| Catalytic Materials | Over 80% of publications [14] | --- | Energy Generation, Chemical Synthesis |

A review of high-throughput methodologies reveals a pronounced imbalance in research focus. Over 80% of publications are concentrated on catalytic materials, creating a significant shortage of research into other crucial material classes essential for full system integration, such as ionomers, membranes, and electrolytes [14]. Furthermore, the screening criteria for new materials often overlook critical economic and safety factors; less than 20% of studies consider cost, availability, and safety in their primary discovery metrics, which are crucial for assessing real-world economic feasibility [14].

Table 2: Global Distribution of High-Throughput Electrochemical Materials Research [14]

| Region/Country | Research Activity Level | Primary Focus Areas | Collaboration Opportunity |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | High | Catalysts, AI-Driven Discovery | Data Sharing, Policy Alignment |

| Select European Countries | High | Catalysts, Computational Methods | Cross-Border Facilities Access |

| Select Asian Countries | High | Catalysts, Battery Materials | Open Data Initiatives |

| Most Other Countries | Low or None | --- | Capacity Building, Resource Sharing |

The implementation of high-throughput electrochemical materials discovery is geographically concentrated, with research activity confined to a handful of countries [14]. This concentration reveals a substantial global opportunity for collaboration and data sharing to accelerate discovery. Simultaneously, diversity gaps in the scientific workforce present another challenge to innovation. For instance, in the U.S., Hispanic workers make up 17% of the total workforce but only 8% of the STEM workforce, and Black workers comprise 11% of all employed adults but only 9% of those in STEM occupations [19]. These representation gaps are particularly pronounced in fields like engineering and architecture, where Black workers comprise just 5% of the workforce [19].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Screening of Non-Catalytic Materials

This protocol provides a methodology for extending high-throughput screening to underrepresented material classes such as ionomers, membranes, and electrolytes.

Objective: To establish a reproducible high-throughput workflow for synthesizing and characterizing the properties of non-catalytic electrochemical materials, with integrated assessment of cost and safety.

Materials:

- High-Throughput Synthesizer: For parallel synthesis of material libraries (e.g., combinatorial inkjet printer or automated pipetting system).

- Robotic Characterization Suite: Includes impedance analyzers, gas permeation cells, and mechanical testers.

- Computational Resources: For Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations and data management.

- Chemical Database: Library of polymer precursors, salts, solvents, and inorganic particles.

Procedure:

- Design of Experiment (DoE):

- Define the compositional space for the target material (e.g., polymer blends for ionomers, salt concentrations for electrolytes).

- Use statistical software to generate a library of distinct compositions for synthesis, ensuring coverage of a wide property space.

Automated Synthesis:

- Program the high-throughput synthesizer to prepare material samples according to the DoE library.

- For ionomer membranes, this may involve automated casting and drying processes in a 96-well format.

Parallel Property Screening:

- Ionic Conductivity: Use a multi-channel impedance analyzer to measure conductivity across all samples.

- Chemical Stability: Expose samples to relevant environments (e.g., acidic/alkaline conditions) in parallel and assess degradation via automated imaging or weight tracking.

- Mechanical Integrity: Perform high-throughput tensile or puncture tests using a robotic system.

Integrated Cost & Safety Analysis:

- Integrate with cost databases of precursor materials to automatically calculate raw material cost per unit.

- Flag compounds containing critical raw materials or substances of very high concern (SVHC) based on regulatory lists.

Data Fusion and Down-Selection:

- Aggregate all property, cost, and safety data into a single database.

- Apply multi-objective optimization algorithms to down-select the top 5-10 candidate materials for further validation.

Protocol 2: Establishing an International Collaborative Screening Pipeline

This protocol outlines a framework for distributing high-throughput screening tasks across international research partners to leverage global expertise and resources.

Objective: To create a standardized and equitable workflow for distributing and reconciling high-throughput computational and experimental tasks among international collaborators.

Materials:

- Cloud-Based Data Platform: A centralized repository for computational models, experimental data, and standard operating procedures (SOPs).

- Standardized Material Kits: Pre-packaged and shipped kits of precursor materials to ensure experimental consistency across labs.

- Communication Infrastructure: Secure video conferencing and project management tools.

Procedure:

- Project Scoping & Task Division:

- Partner laboratories meet to define the research goal and divide the material space (e.g., by elemental composition or material class).

- Clearly assign computational and experimental responsibilities to each partner based on their expertise and infrastructure.

Standardization and Calibration:

- All partners adopt identical computational parameters (e.g., DFT functionals, convergence criteria).

- For experimental work, a "round-robin" test is conducted where all partners analyze the same control sample to calibrate equipment and techniques.

Distributed Execution:

- Computational Hub: One partner manages high-throughput DFT calculations, screening for thermodynamic stability and electronic properties.

- Experimental Hubs: Other partners focus on parallel synthesis and testing based on the computational predictions.

- All data is uploaded to the cloud platform in a pre-defined, standardized format in real-time.

Data Reconciliation and Model Refinement:

- Use machine learning to correlate computational predictions with experimental outcomes from the distributed network.

- Periodically refine the computational models based on the aggregated experimental data to improve prediction accuracy for subsequent screening rounds.

Validation and Intellectual Property (IP) Management:

- The most promising candidates from the distributed screening are validated independently by two or more partners.

- A pre-established IP agreement, defining contribution-based ownership, governs the management of any resulting discoveries.

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for High-Throughput Catalyst Discovery

| Item | Function in Protocol | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Salt Library | Provides elemental constituents for catalyst synthesis. | e.g., NiCl₂, H₂PtCl₆, AgNO₃ for bimetallic alloys [4]. |

| DFT Calculation Software | Predicts formation energy and electronic structure. | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO; used for initial stability screening [4]. |

| DOS Similarity Metric | Descriptor for identifying Pd-like catalysts. | Quantifies similarity to reference catalyst (e.g., Pd) [4]. |

| Phase-Change Materials (PCMs) | Thermal energy storage mediums for reactivity studies. | Paraffin wax, salt hydrates [20]. |

| Automated Synthesis Robot | Enables parallel synthesis of material libraries. | Crucial for creating compositional spreads for screening [14]. |

| Cloud Data Platform | Centralized repository for collaborative data sharing. | Essential for international collaboration pipelines [14]. |

| Standardized Material Kits | Ensures experimental consistency across partner labs. | Pre-measured precursors shipped to all collaborators. |

The Role of Autonomous Labs and Closed-Loop Discovery Processes

Autonomous laboratories, often termed "self-driving labs," represent a paradigm shift in scientific research, particularly in catalyst discovery and materials science. These systems integrate artificial intelligence (AI), robotic experimentation, and automation technologies into a continuous closed-loop cycle, enabling the execution of scientific experiments with minimal human intervention [21]. This approach fundamentally accelerates the exploration of vast chemical and material spaces, which is critical for developing sustainable technologies and new therapeutics.

The core of an autonomous lab is a closed-loop experimental cycle where AI generates hypotheses, robotic systems execute experiments, and data analysis algorithms interpret results to inform the next cycle of experimentation [21] [22]. This continuous process minimizes downtime between experiments, eliminates subjective decision points, and enables rapid optimization strategies. For catalyst discovery—a field traditionally characterized by time-intensive trial-and-error approaches—this autonomous paradigm reduces discovery timelines from years to days or weeks [21] [23].

Table 1: Impact Assessment of Autonomous Laboratory Implementation

| Metric | Traditional Approach | Autonomous Lab Approach | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment Throughput | 20-30 screens/quarter | 50-85 screens/quarter | [24] |

| Condition Evaluation | <500 conditions/quarter | ~2000 conditions/quarter | [24] |

| Material Discovery Rate | Months to years | Weeks | [21] [23] |

| Development Cost Reduction | Baseline | ~25% reduction | [22] |

| R&D Cycle Time | Baseline | Reduction by >500 days | [22] |

Core Components and Technologies

Architectural Framework

Autonomous laboratories feature a modular architecture that physically and computationally integrates several key components. The hardware layer typically includes robotic automation systems (liquid handlers, mobile sample transport robots), analytical instruments (mass spectrometers, plate readers, NMR), and environmental control modules (incubators, gloveboxes) [25]. A notable feature of advanced systems like the Autonomous Lab (ANL) is their modular design with devices installed on movable carts, allowing reconfiguration to suit specific experimental needs [25].

The software layer consists of AI planning algorithms, data analysis tools, and integration middleware that controls hardware components. This layered architecture creates a continuous workflow where AI-driven experimental design directly interfaces with robotic execution systems, and analytical data feeds back to optimization algorithms [21] [25].

AI and Machine Learning Technologies

Artificial intelligence serves as the "brain" of autonomous laboratories, with several specialized technologies enabling closed-loop operation:

Experimental Planning and Optimization: AI systems employ algorithms such as Bayesian optimization to design experiments that efficiently explore parameter spaces. For instance, the ANL system used Bayesian optimization to adjust concentrations of medium components to maximize cell growth and glutamic acid production in E. coli [25]. Reinforcement learning further enables adaptive control based on experimental outcomes.

Large Language Models (LLMs): Systems like Coscientist and ChemCrow utilize LLMs with tool-using capabilities to plan and execute complex chemical experiments. These systems can design synthetic routes, control robotic hardware, and analyze results [21]. ChemAgents employs a hierarchical multi-agent system with role-specific agents (Literature Reader, Experiment Designer, etc.) coordinated by a central Task Manager [21].

Data Analysis and Interpretation: Machine learning models, including convolutional neural networks, process analytical data from various characterization techniques. The A-Lab system used ML models for precursor selection and X-ray diffraction phase analysis, enabling real-time interpretation of experimental outcomes [21].

Cross-Domain Foundation Models: Emerging AI approaches use foundation models trained on diverse scientific data to predict material properties and propose synthesis routes, creating synergy between computational prediction and experimental validation [22] [23].

Figure 1: Closed-loop workflow in autonomous laboratories showing the continuous cycle of AI-driven design, robotic execution, analytical measurement, and data-driven learning.

Application Notes for Catalyst Discovery

High-Throughput Computational-Experimental Screening

The integration of high-throughput computational screening with experimental validation has proven highly effective for discovering novel bimetallic catalysts. In one representative study, researchers developed a protocol to identify Pd-replacement catalysts using electronic density of states (DOS) similarity as a screening descriptor [4]. The workflow began with first-principles calculations screening 4,350 bimetallic alloy structures, followed by experimental validation of top candidates.

The computational phase employed density functional theory (DFT) to calculate formation energies and DOS patterns for each alloy. The similarity between each candidate's DOS pattern and that of Pd(111) surface was quantified using a specialized metric that applied greater weight to regions near the Fermi energy [4]. This approach identified eight promising candidates from the initial library, four of which demonstrated catalytic performance comparable to Pd in experimental testing for H2O2 direct synthesis. Notably, the Pd-free Ni61Pt39 catalyst exhibited a 9.5-fold enhancement in cost-normalized productivity compared to Pd [4].

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Selected Catalysts from High-Throughput Screening

| Catalyst | DOS Similarity to Pd | H2O2 Synthesis Performance | Cost-Normalized Productivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pd (Reference) | 0 (by definition) | Baseline | 1.0 (Baseline) |

| Ni61Pt39 | Low | Comparable to Pd | 9.5x enhancement |

| Au51Pd49 | Low | Comparable to Pd | Not specified |

| Pt52Pd48 | Low | Comparable to Pd | Not specified |

| Pd52Ni48 | Low | Comparable to Pd | Not specified |

Fluorogenic High-Throughput Kinetic Screening

For catalyst discovery and kinetic profiling, researchers have developed automated, real-time optical scanning approaches that leverage fluorogenic probes. One innovative platform screened 114 different catalysts for nitro-to-amine reduction using a simple "on-off" fluorescence probe that produces a strong fluorescent signal when the non-fluorescent nitro-moiety is reduced to its amine form [26].

This system utilized 24-well polystyrene plates with each reaction well containing catalyst, fluorogenic probe, and reagents, paired with reference wells containing the final amine product. A plate reader performed orbital shaking followed by fluorescence and absorption scanning every 5 minutes for 80 minutes, generating time-resolved kinetic data for each catalyst [26]. This approach collected over 7,000 data points, enabling comprehensive assessment of catalyst performance based on reaction completion times, selectivity, and the presence of intermediates.

The methodology enabled multidimensional evaluation incorporating not just catalytic activity but also material abundance, price, recoverability, and safety. The integration of environmental considerations directly into the screening process promotes selection of sustainable catalytic materials, moving beyond pure performance metrics [26].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Screening of Bimetallic Catalysts Using DOS Similarity

Objective: Identify bimetallic catalysts with performance comparable to precious metal catalysts using computational-experimental screening.

Materials:

- DFT computation cluster

- High-throughput synthesis platform

- Catalyst testing reactor system

- Analytical equipment (HPLC, GC-MS)

Procedure:

Computational Screening Phase:

- Select binary systems from transition metals in periods IV, V, and VI (435 binary systems at 1:1 composition) [4].

- For each system, evaluate 10 ordered crystal structures (B1, B2, B3, B4, B11, B19, B27, B33, L10, L11), totaling 4,350 structures.

- Calculate formation energy (ΔEf) for each structure using DFT. Filter systems with ΔEf < 0.1 eV to ensure thermodynamic stability.

- For thermodynamically stable alloys, compute density of states (DOS) patterns projected on close-packed surfaces.

- Quantify similarity to reference catalyst (e.g., Pd(111)) using ΔDOS metric with Gaussian weighting (σ = 7 eV) near Fermi energy [4].

- Select top candidates with lowest ΔDOS values for experimental validation.

Experimental Validation Phase:

- Synthesize selected bimetallic catalysts using appropriate methods (impregnation, co-precipitation, etc.).

- Evaluate catalytic performance for target reaction (e.g., H2O2 direct synthesis) under standardized conditions.

- Compare activity, selectivity, and stability to reference catalyst.

- Calculate cost-normalized productivity considering catalyst composition and precious metal content.

Troubleshooting:

- For immiscible elements with positive ΔEf, consider nonequilibrium synthesis methods.

- If experimental performance doesn't correlate with DOS similarity, verify surface composition matches computational models.

Protocol 2: Real-Time Fluorogenic Kinetic Screening of Catalyst Libraries

Objective: Simultaneously screen multiple catalysts for reduction reactions using real-time fluorescence monitoring.

Materials:

- 24-well polystyrene plates

- Nitronaphthalimide (NN) fluorogenic probe

- Catalyst library (114 catalysts)

- Biotek Synergy HTX multi-mode plate reader

- Aqueous N2H4 (1.0 M)

- Acetic acid (0.1 mM)

Procedure:

Plate Setup:

- Prepare reaction wells: each contains 0.01 mg/mL catalyst, 30 µM NN, 1.0 M aqueous N2H4, 0.1 mM acetic acid, H2O (total volume 1.0 mL) [26].

- Prepare reference wells: identical composition but with NN replaced by reduced amine product (AN).

- Arrange plate with 12 reaction wells and 12 corresponding reference wells.

Kinetic Data Collection:

- Initiate reactions simultaneously.

- Place plate in pre-programmed multi-mode reader.

- Set cycle: 5 seconds orbital shaking → fluorescence scan (excitation 485 nm, emission 590 nm) → absorption spectrum (300-650 nm) [26].

- Repeat cycle every 5 minutes for 80 minutes.

- For fast-reacting systems, implement fast kinetics protocol with additional early timepoints.

Data Processing:

- Convert raw data to CSV format and import to database.

- Generate kinetic graphs for each catalyst: absorption decay at 350 nm (nitro form), growth at 430 nm (amine product), fluorescence intensity, and isosbestic point stability.

- Calculate reaction rates, completion times, and selectivity based on intermediate formation.

Catalyst Scoring:

- Evaluate catalysts based on multiple criteria: reaction completion time, material abundance, price, recoverability, and safety.

- Apply weighting factors emphasizing green chemistry principles where appropriate.

- Rank catalysts by cumulative score for further development.

Troubleshooting:

- If isosbestic point not stable, suspect side reactions or intermediate accumulation.

- For low fluorescence signal, verify probe concentration and catalyst dispersion.

Figure 2: Integrated computational-experimental screening protocol for accelerated catalyst discovery, showing the continuous feedback between simulation and validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Autonomous Catalyst Screening

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitronaphthalimide (NN) probe | Fluorogenic substrate for reduction reactions | Real-time kinetic screening of nitro-to-amine reduction catalysts [26] | Exhibits shift in absorbance and strong fluorescence upon reduction to amine form |

| Bimetallic alloy libraries | Catalyst candidates for high-throughput screening | Discovery of Pd-replacement catalysts for H2O2 synthesis [4] | Pre-screened for thermodynamic stability (ΔEf < 0.1 eV) |

| Aqueous hydrazine (N2H4) | Reducing agent for catalytic reduction reactions | Nitro-to-amine reduction screening platform [26] | Used at 1.0 M concentration in fluorogenic assay |

| M9 minimal medium | Defined growth medium for microbial biocatalyst studies | Optimization of E. coli culture conditions for glutamic acid production [25] | Enables precise control of nutrient concentrations during bioprocess optimization |

| Bayesian optimization algorithms | AI-driven experimental planning and parameter optimization | Autonomous optimization of culture medium components [25] | Efficiently explores multi-dimensional parameter spaces with minimal experiments |

| Modular robotic platforms (e.g., CHRONECT XPR) | Automated solid and liquid handling for HTE | High-throughput catalyst screening at AstraZeneca [24] | Enables dosing of 1 mg to several grams with <10% deviation at low masses |

Implementation Considerations and Challenges

While autonomous laboratories offer transformative potential for catalyst discovery, several practical challenges must be addressed for successful implementation. Data quality and scarcity present significant hurdles, as AI models require high-quality, diverse training data, while experimental data often suffer from noise and inconsistent sources [21]. Developing standardized experimental data formats and utilizing high-quality simulation data with uncertainty analysis can help mitigate these issues.

Hardware integration remains challenging due to the diverse instrumentation requirements for different chemical tasks. Solid-phase synthesis necessitates furnaces and powder handling, while organic synthesis requires liquid handling and NMR [21]. Developing standardized interfaces that accommodate rapid reconfiguration of different instruments is essential for flexible autonomous systems.

AI model generalization is another critical challenge, as most autonomous systems and AI models are highly specialized for specific reaction types or material systems. Transfer learning and meta-learning approaches can help adapt models to new domains with limited data [21]. Additionally, LLM-based decision-making systems sometimes generate plausible but incorrect chemical information, necessitating targeted human oversight during development [21].

Successful implementation, as demonstrated by AstraZeneca's 20-year HTE journey, requires close collaboration between automation specialists and domain scientists. Colocating these experts enables a cooperative rather than service-led approach, fostering innovation and practical problem-solving [24].

Implementing High-Throughput Screening: Computational and Experimental Approaches

The discovery and development of advanced materials, particularly catalysts, are pivotal for addressing global challenges in sustainable energy and green chemical production. Traditional research paradigms, reliant on empirical trial-and-error or theoretical simulations alone, are increasingly limited by inefficiencies when navigating vast chemical spaces [27]. The integration of Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Machine Learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative approach, creating accelerated, high-throughput workflows for catalyst discovery [14] [28]. This paradigm leverages the physical insights of first-principles computations with the pattern recognition and predictive power of data-driven models, enabling the rapid screening and design of novel materials with tailored properties [27]. This document outlines detailed application notes and protocols for implementing these integrated computational workflows, framed within the context of high-throughput screening for catalyst discovery research.

Foundational Concepts and Synergies

The Distinct Roles of DFT and ML

In integrated workflows, DFT and ML are not competing tools but complementary technologies that address each other's limitations.

- Density Functional Theory (DFT) serves as a high-fidelity data generator. It provides quantum-mechanical-level calculations of material properties, such as formation energies, electronic band structures, and adsorption energies of reaction intermediates [28] [29]. While highly insightful, DFT is computationally expensive, making exhaustive screening of large material databases prohibitive.

- Machine Learning (ML) acts as a fast, surrogate model. ML algorithms are trained on datasets derived from DFT calculations (or experiments) to learn the complex relationships between a material's composition, structure, and its properties [28] [27]. Once trained, an ML model can predict material properties instantaneously and at a fraction of the computational cost of DFT, enabling rapid exploration of vast chemical spaces.

Techniques for Integration

The synergy between DFT and ML is achieved through several technical approaches:

- Descriptor-Based Prediction: ML models use features (descriptors) derived from a material's composition (e.g., elemental concentrations, atomic numbers) or structure (e.g., symmetry, radial distribution functions) to predict target properties like catalytic activity or stability [27] [30].

- Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs): MLIPs are trained on DFT-generated energies and forces to create potentials that approach the accuracy of DFT but with the computational speed of classical force fields, enabling large-scale molecular dynamics simulations [28].

- Error Correction: ML can be employed to correct systematic errors in DFT. For instance, neural networks can learn the discrepancy between DFT-calculated and experimentally measured properties (e.g., formation enthalpies), thereby improving the reliability of first-principles predictions [30].

Application Notes and Protocols

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for a representative high-throughput screening workflow aimed at discovering novel solid-state catalysts.

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Screening of Catalytic Materials

Aim: To systematically identify promising catalyst candidates for a target reaction (e.g., hydrogen evolution reaction) from a large space of ternary alloys.

Workflow Overview: The following diagram illustrates the integrated DFT and ML screening pipeline.

Detailed Methodology:

Step 1: Define the Exploration Space and Initial Data Generation

- Objective: Select a constrained chemical space (e.g., Al-Ni-Pd ternary system) and generate an initial dataset for ML training [30].

- Procedure:

- Curate a list of potential binary and ternary compounds and alloys from existing materials databases.

- Perform high-throughput DFT calculations for these structures to compute key properties. Essential properties for catalysis include:

- Utilize high-throughput computational frameworks, ensuring consistent calculation parameters (e.g., k-point mesh, exchange-correlation functional) across all systems.

Step 2: Construct a Structured Materials Database

- Objective: Assemble DFT results into a structured and labeled database.

- Procedure:

- For each material, store its composition, crystal structure, and the computed DFT properties.

- Generate a set of machine-readable descriptors. Initial features can include:

- Normalize all features to prevent scaling biases in the ML model.

Step 3: Train Machine Learning Models

- Objective: Develop accurate surrogate models to predict material properties.

- Procedure:

- Model Selection: Begin with tree-based models (e.g., XGBoost) or neural networks (Multi-layer Perceptrons) for regression tasks [27] [30].

- Training: Use the structured database to train models to predict a target property (e.g., adsorption energy) from the input descriptors.

- Validation: Implement rigorous validation techniques such as k-fold cross-validation and leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) to prevent overfitting and ensure model generalizability [27] [30].

- Evaluation: Assess model performance using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) against a held-out test set.

Step 4: High-Throughput Screening and Validation

- Objective: Use the trained ML model to screen a vast virtual library of materials and validate top candidates.

- Procedure:

- Apply the ML model to predict the properties of thousands to millions of candidate materials within the defined chemical space.

- Filter and rank candidates based on desired property thresholds (e.g., high stability, optimal adsorption energy).

- Select the top-ranking candidates and perform higher-fidelity DFT calculations to validate the ML predictions. This step confirms the results and filters out false positives.

- The most promising candidates from DFT validation are recommended for experimental synthesis and testing.

Protocol 2: ML-Augmented DFT for Accurate Phase Stability

Aim: To improve the accuracy of DFT-predicted formation enthalpies and phase stability in ternary alloy systems using a neural network-based error correction method [30].

Workflow:

Step 1: Data Curation

- Compile a dataset of binary and ternary alloys with both DFT-calculated and experimentally measured formation enthalpies (Hf).

- Filter the data to exclude unreliable or missing values.

Step 2: Error Learning

- The target variable for the ML model is the error, defined as: ( \Delta Hf = H{f}^{(\text{exp})} - H_{f}^{(\text{DFT})} ).

- Train a neural network (e.g., a Multi-layer Perceptron with three hidden layers) to predict ( \Delta H_f ) using the same structured feature set described in Protocol 1 [30].

Step 3: Prediction and Correction

- For a new material, calculate ( H{f}^{(\text{DFT})} ) and use the trained NN to predict the error ( \Delta Hf^{(\text{pred})} ).

- The corrected, more accurate formation enthalpy is: ( H{f}^{(\text{corrected})} = H{f}^{(\text{DFT})} + \Delta H_f^{(\text{pred})} ).

- This corrected value is then used for constructing accurate phase diagrams and assessing phase stability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

The following table details key software and computational methods that form the essential "reagent solutions" for implementing integrated DFT-ML workflows.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DFT-ML Workflows

| Software/Method | Category | Primary Function | Key Application in Workflows |

|---|---|---|---|

| VASP [29] | DFT Code | Planewave-based electronic structure calculations. | High-throughput computation of formation energies, band structures, and adsorption energies for database generation. |

| Quantum ESPRESSO [29] | DFT Code | Open-source suite for DFT and molecular dynamics. | An accessible alternative for performing first-principles calculations in automated workflows. |

| XGBoost [27] | ML Algorithm | Supervised learning using gradient-boosted decision trees. | Rapid and accurate prediction of material properties from descriptors; often used for initial screening. |

| Multi-layer Perceptron (MLP) [30] | ML Algorithm | A class of feedforward artificial neural network. | Modeling complex, non-linear relationships in materials data, such as error correction in formation enthalpies. |

| SISSO [27] | ML Method | Compressed-sensing for identifying optimal descriptors. | Ascertaining the most relevant physical descriptors from a huge pool of candidate features. |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) [28] | ML Method | Potentials trained on DFT data for fast, accurate MD. | Enabling large-scale and long-time-scale simulations of catalytic surfaces and reaction dynamics. |

Quantitative Data and Performance Metrics

The efficacy of integrated DFT-ML workflows is demonstrated by key performance metrics, including accuracy and computational speed-up.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of DFT-ML Workflows in Catalysis Research

| Application Domain | ML Model Used | Key Performance Metric | Result / Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Screening [27] | Graph Neural Networks, Random Forest | High-accuracy prediction of adsorption energies. | Achieves predictive accuracy comparable to DFT at a fraction of the computational cost, enabling vast chemical space exploration. |

| Phase Stability [30] | Neural Network (MLP) | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) in formation enthalpy. | Significantly reduces error in DFT-predicted formation enthalpies for Al-Ni-Pd and Al-Ni-Ti systems, improving phase diagram reliability. |

| Band Gap Prediction [28] | Models trained on DFT data | Prediction accuracy vs. computational cost. | Predicts electronic properties with high accuracy at reduced computational costs, expanding the scope of screenable chemistries. |

| Workflow Efficiency [14] | Hybrid DFT/ML/Experiment | Acceleration of discovery timeline. | Closed-loop autonomous labs integrate computation, experiment, and AI to drastically reduce the time from hypothesis to new material identification. |

The exploration of complex chemical spaces for catalyst discovery necessitates a paradigm shift from traditional, labor-intensive experimental methods. Advanced High-Throughput Screening (HTS) platforms that integrate automation, miniaturization, and data science are now at the forefront of this transformation [31] [32]. These systems are specifically engineered to manage the high-dimensionality of material design spaces, which is a task that surpasses human capability for efficient exploration. By leveraging technologies such as microfluidics and automated robotics, these platforms enable the rapid and cost-effective screening of thousands of candidate materials or compounds, dramatically accelerating the innovation cycle [33] [32].

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) forms the intellectual core of modern HTS, creating a powerful feedback loop for experimental design and data analysis [31] [32]. This synergy is particularly potent in electro-catalyst discovery, where active learning techniques like Bayesian optimization guide the iterative process of proposing new experiments, synthesizing candidates, and characterizing their performance for reactions such as oxygen evolution, hydrogen evolution, and CO2 reduction [31]. Consequently, these platforms not only expedite the discovery of novel high-performance materials but also facilitate the extraction of fundamental chemistry-structure-property relationships that were previously inaccessible [31].

Microfluidic HTS Platforms

Microfluidic HTS revolutionizes traditional screening by miniaturizing and parallelizing laboratory processes onto a single chip. These systems manipulate tiny fluid volumes (often below 10 µl) within microscale channels and chambers to perform rapid, highly controlled experiments [10] [33]. The core strength of microfluidics lies in its ability to precisely deliver reagents, control local environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, pressure), and monitor reactions in real-time, all while operating with minimal reagent consumption [33]. This precision leads to more reliable and reproducible results compared to conventional methods. Furthermore, microfluidic devices can be designed to create conditions that closely mimic real biological or catalytic environments, thereby enhancing the physiological relevance of screening outcomes for biomedical and catalytic applications [33]. The technology is a cornerstone for the ongoing development of targeted, personalized therapies and efficient catalyst discovery.

Automated Robotic Assay Systems

Automated robotic systems represent a physical integration platform, combining robotic liquid handlers, automated synthesis reactors, and high-sensitivity detectors to execute extensive experimental workflows with minimal human intervention [31] [32]. A key application is Quantitative HTS (qHTS), which involves assaying complete compound libraries across a series of dilutions to generate full concentration-response profiles for every substance [10] [34]. These platforms operate reliably in high-density plate formats (e.g., 1536-well plates), enabling the vertical development of inter-plate titration series [34]. The true transformative power of these systems is unlocked when they are coupled with AI. This integration gives rise to autonomous or "self-driving" laboratories, often termed AI chemists or robotic AI chemists [32]. These systems can autonomously execute tasks ranging from the theoretical design of catalyst components and the optimization of synthesis conditions to high-throughput preparation and performance testing, effectively closing the loop between data acquisition and experimental decision-making [32].

Platform Comparison Table

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of these two HTS platform types.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Microfluidic and Automated Robotic HTS Platforms

| Feature | Microfluidic HTS Platforms [33] | Automated Robotic Assay Systems [31] [10] [34] |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | High, enabled by massive parallelization on a single chip. | High, enabled by robotic automation of standard plate-based assays. |

| Sample Volume | Very low (e.g., <10 µl per test). | Low (e.g., <10 µl per well in 1536-well plates). |

| Key Strengths | High precision control, low cost per test, mimics real environments. | High reliability, flexibility for complex workflows, seamless integration with AI. |

| Primary Applications | Drug screening, biomolecule analysis, condition optimization. | qHTS, catalyst discovery and optimization, electrolyte screening. |

| Automation & AI Integration | Platform for controlled data generation; can be part of a larger automated system. | Core component for creating closed-loop, autonomous discovery systems (AI chemists). |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Quantitative HTS (qHTS) in Catalyst Discovery

This protocol outlines the process for performing a qHTS assay to evaluate a library of catalyst candidates, adapted for automated systems [10] [34].

Step 1: Compound Library and Plate Preparation

- Prepare a master library of catalyst precursors or compounds in a 384-well format.