H-ZSM-5 vs. H-Beta: A Comprehensive Comparison of Catalytic Performance for Researchers

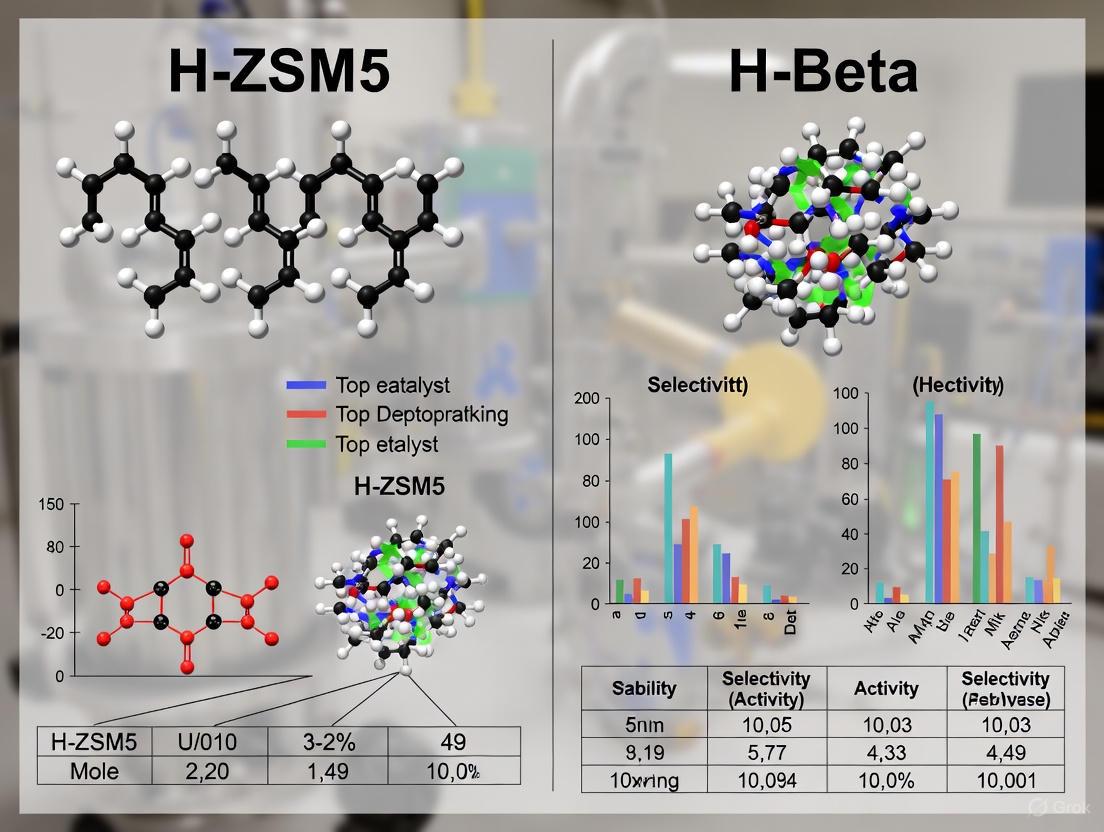

This article provides a systematic comparison of H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta zeolite catalysts, addressing the critical factors that influence their performance in chemical processes relevant to pharmaceutical and industrial applications.

H-ZSM-5 vs. H-Beta: A Comprehensive Comparison of Catalytic Performance for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta zeolite catalysts, addressing the critical factors that influence their performance in chemical processes relevant to pharmaceutical and industrial applications. We explore the foundational structural and acidic properties of these catalysts, their efficacy in key reactions like methylation and hydrocarbon conversion, and strategies for optimizing performance and mitigating deactivation. By synthesizing validation data and direct performance comparisons, this review serves as a guide for researchers and scientists in selecting and tailoring zeolite catalysts for specific catalytic challenges, with implications for process development in fine chemicals and pharmaceutical synthesis.

Understanding the Blueprint: Core Structural and Acidic Properties of H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta

Zeolites are crystalline, microporous aluminosilicates that are indispensable in industrial applications as catalysts, adsorbents, and ion exchangers [1]. Their catalytic performance is profoundly influenced by their framework topology, which governs the size, shape, and connectivity of the internal pore system. Among the numerous known zeolite frameworks, MFI (ZSM-5) and BEA (Beta) are two of the most industrially significant and widely studied. The MFI framework, exemplified by H-ZSM-5, and the BEA framework, exemplified by H-Beta, possess distinct architectural features that dictate their mass transport properties, active site accessibility, and ultimate shape selectivity. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these two framework structures, focusing on their pore architecture and its direct impact on catalytic performance, to aid researchers in selecting the appropriate catalyst for their specific processes.

Structural Comparison: MFI vs. BEA

The fundamental differences between the MFI and BEA frameworks originate from their unique crystalline structures and the geometry of their pore systems.

MFI (H-ZSM-5) Framework: The MFI topology features a bidirectional, 10-membered ring (10-MR) pore system. This system consists of straight channels (apertures of approximately 5.4 × 5.6 Å) running parallel to the b-axis, which intersect with sinusoidal channels (apertures of approximately 5.1 × 5.4 Å) running parallel to the a-axis [2] [3]. This creates a three-dimensional network with medium pore size. The crystals often exhibit a coffin-like morphology, and the straight channels open at the [010] facet, while the sinusoidal channels open at the [100] and [101] facets [2] [3].

BEA (H-Beta) Framework: The BEA topology is characterized by a tridirectional, 12-membered ring (12-MR) pore system. It possesses larger pores than MFI, with each channel direction having an aperture of approximately 6.7 × 6.7 Å [3]. A key structural complexity of BEA is that it is not a single polymorph but an intergrowth of two distinct polymorphs (A and B) [4]. This intergrowth, along with the presence of stacking faults, can further restrict molecular movement through the sinusoidal pores [3]. BEA crystals commonly have a truncated bipyramidal morphology [3].

Table 1: Fundamental Structural Properties of MFI and BEA Zeolites.

| Property | MFI (H-ZSM-5) | BEA (H-Beta) |

|---|---|---|

| Pore System Dimensionality | 3D | 3D |

| Pore Channel Types | Straight & Sinusoidal | Straight & Sinusoidal |

| Pore Ring Size | 10-Membered Ring | 12-Membered Ring |

| Straight Channel Aperture | 5.4 × 5.6 Å [2] | ~6.7 × 6.7 Å [3] |

| Sinusoidal Channel Aperture | 5.1 × 5.4 Å [2] | Smaller effective diameter due to zig-zag shape [3] |

| Typical Crystal Morphology | Coffin-like [2] | Truncated Bipyramidal [3] |

| Key Structural Feature | Bidirectional channel system | Polymorphic intergrowth |

The following diagram illustrates the distinct pore architectures and their connectivity in the two frameworks.

Catalytic Performance and Shape Selectivity

The structural differences between MFI and BEA directly translate to distinct catalytic behaviors, particularly in activity, selectivity, and deactivation resistance. The smaller pore apertures of MFI impose significant mass transfer limitations and confer a pronounced shape selectivity, favoring reactions involving linear molecules or preventing the formation and egress of bulky products. In contrast, the larger pores of BEA facilitate access and diffusion for a wider range of reactants and products, including aromatic and branched species.

Case Study: Benzene Methylation by Methanol

A combined experimental-theoretical study provides a direct, quantitative comparison of the methylation of benzene by methanol over H-ZSM-5 (MFI) and H-Beta (BEA) catalysts with similar acid site densities and crystal sizes [5].

- Activity: The study found a consistently higher benzene methylation rate on H-ZSM-5 versus H-Beta [5]. This was attributed to more favorable host-guest interactions within the MFI pores, which outweighed the greater loss of entropy compared to the larger-pore BEA framework.

- Reaction Relevance: Methylation is a key elementary step in the Methanol-to-Hydrocarbons (MTH) process. While both zeolites show MTH-activity, the product distribution differs significantly. H-Beta, due to its large-pore structure, produces predominantly larger components like hexamethylbenzene, which are too heavy for gasoline and act as coke precursors, leading to rapid deactivation. This makes H-Beta unsuitable for industrial MTH applications despite its academic interest [5].

Table 2: Catalytic Performance Comparison in Benzene Methylation and MTH Chemistry.

| Performance Metric | H-ZSM-5 (MFI) | H-Beta (BEA) |

|---|---|---|

| Benzene Methylation Rate | Higher [5] | Lower [5] |

| Host-Guest Interactions | More Favorable [5] | Less Favorable [5] |

| Typical MTH Products | Light olefins (C2-C4), Gasoline-range hydrocarbons [5] | Predominantly larger aromatics (e.g., Hexamethylbenzene) [5] |

| Deactivation (Coking) Tendency | More resistant [5] | Rapid deactivation [5] |

| Industrial MTH Suitability | High (archetypal catalyst) [5] | Low (academic interest) [5] |

Case Study: Olefin Catalytic Cracking (OCC) and Diffusion

The catalytic cracking of C4 olefins (OCC) to produce ethylene and propylene on H-ZSM-5 highlights the critical role of morphology and diffusion anisotropy. Research shows that regulating the crystal morphology of H-ZSM-5, specifically by controlling the length along the c-axis, directly impacts catalytic activity and stability [2].

- Descriptor: A diffusion anisotropy descriptor was introduced, linking the improved catalytic performance in samples with a longer c-axis to a higher proportion of straight channels being exposed on the crystal surface [2].

- Mechanism: Molecules like C4 olefins experience anisotropic diffusion within the MFI framework; their escape rates differ between the straight and sinusoidal channels. Crystals with a higher exposed degree of the [010] facet (where straight channels open) provide more facile diffusion pathways for reactants and products, leading to enhanced activity and reduced deactivation [2]. This underscores that for a given framework, catalytic performance can be optimized by engineering crystal morphology to leverage its intrinsic diffusion properties.

Experimental Protocols for Comparative Studies

To obtain the kinetic and catalytic performance data cited in this guide, specific and rigorous experimental protocols must be followed.

Protocol for Kinetic Measurement of Benzene Methylation

This protocol is derived from the study that compared methylation rates over H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta [5].

Catalyst Preparation and Characterization:

- Synthesis: H-ZSM-5 can be obtained commercially (e.g., from Süd Chemie). H-Beta is often synthesized in-house via hydrothermal synthesis using sources like sodium aluminate and sodium silicate in a tetraethylammonium hydroxide solution [5].

- Characterization: Confirm high crystallinity using X-ray Diffraction (XRD). Determine textural properties (BET surface area, pore volume) via Ar physisorption. Verify Si/Al ratio and acid site density using Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) analysis and Pyridine-adsorption FTIR, respectively. Ensure both catalysts have similar acid site densities and small, comparable crystallite sizes to minimize diffusion limitations [5].

Catalytic Testing:

- Reactor: Use a fixed-bed tubular reactor operating at high weight hourly space velocity (WHSV) to achieve low conversion [5].

- Reaction Conditions: Feed consists of benzene and methanol. Temperature is typically between 453-533 K [5].

- Product Analysis: Effluent is monitored using an online Gas Chromatograph (GC) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) [5].

Data Analysis:

- Kinetic Parameters: From the methylation rates at low conversion, determine apparent kinetic coefficients, reaction orders, and Arrhenius parameters. This allows for the direct comparison of the intrinsic methylation step while suppressing side reactions [5].

Protocol for Probing Pore Accessibility with Fluorescent Probes

This protocol uses confocal fluorescence microscopy (CFM) to spatially resolve the internal pore structure and accessibility of zeolite crystals [3].

- Probe Molecules: Employ a series of 4-(4-diethylaminostyryl)-1-methylpyridinium iodide (DAMPI) derived probes with increasing molecular sizes (e.g., from ~5.8 Å to 10.1 Å in diameter) [3].

- Staining Procedure: Submerse large zeolite crystals (e.g., 100×20×20 μm for MFI, 20×10×10 μm for BEA) in solutions of the probe molecules until equilibrium is reached [3].

- Washing: Collect the crystals and wash them thoroughly with ethanol. Note that for acidic zeolites like H-ZSM-5, probes are strongly bound to Brønsted acid sites and are not removed by washing, whereas for siliceous BEA, washing may remove some weakly adsorbed probes [3].

- Imaging and Analysis:

- Use Confocal Fluorescence Microscopy (CFM) to map the fluorescence intensity throughout the crystal volume. This reveals areas of high probe accessibility (e.g., structural imperfections, specific crystal faces) [3].

- Perform polarization-dependent CFM measurements. The rod-shaped DAMPI molecules will align within the zeolite pores, and their fluorescence will be polarized. This polarization dependence can be used to determine the orientation of the pore systems at different locations within the crystal [3].

The workflow for this powerful micro-spectroscopic method is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

This section details essential materials and reagents used in the synthesis, characterization, and catalytic evaluation of MFI and BEA zeolites.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Zeolite Studies.

| Reagent/Material | Function and Role in Research | Exemplary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| H-ZSM-5 Zeolites (Various Si/Al) | Acidic catalyst with shape-selective properties; Si/Al ratio tunes acid strength and site distribution. | Catalytic cracking, benzene methylation [5] [6]. |

| Sodium Aluminate (NaAlO₂) | Aluminum source for the hydrothermal synthesis of zeolite frameworks. | In-house synthesis of H-Beta zeolite [5] [1]. |

| Tetraethylammonium Hydroxide (TEAOH) | Structure-Directing Agent (SDA) or template for guiding the formation of specific zeolite topologies. | Synthesis of H-Beta zeolite [5]. |

| DAMPI Fluorescent Probes | Molecular probes of tunable size for mapping pore accessibility and orientation via CFM. | Probing internal pore structure of MFI and BEA crystals [3]. |

| H-Beta Zeolite | Large-pore acidic catalyst for reactions involving bulky molecules; susceptible to rapid coking. | Study of methylation kinetics and coke formation mechanisms [5]. |

In heterogeneous catalysis, the performance of zeolite catalysts is predominantly governed by the density, strength, and type of their acid sites. Brønsted acid sites are proton donors, while Lewis acid sites are electron pair acceptors; both play critical but distinct roles in catalyzing hydrocarbon reactions. [7] The precise quantification and characterization of these acid sites are fundamental to understanding and optimizing catalytic processes in petroleum refining and chemical production. This guide provides a detailed comparative analysis of two prominent zeolite catalysts: H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta (H-β). By examining their acidity through experimental data and established protocols, we aim to equip researchers with the knowledge to select the appropriate catalyst based on specific process requirements. The focus is on practical measurement techniques and the implications of acid site distribution on catalytic performance, framed within the broader context of catalyst design and selection.

Fundamental Concepts: Brønsted vs. Lewis Acidity

The concepts of acidity extend beyond the classical Arrhenius definition to the more generalized Brønsted-Lowry and Lewis theories.

- Brønsted-Lowry Acids and Bases: A Brønsted acid is a substance that donates a proton (H⁺), while a Brønsted base accepts a proton. In zeolites, Brønsted acidity arises from bridging hydroxyl groups (e.g., Si-OH-Al) in the framework. When a Brønsted acid donates a proton, it forms its conjugate base. Similarly, the relationship between the acid dissociation constant (Kₐ) and base dissociation constant (Kբ) is linked by the water dissociation constant (Kᵥ). [8]

- Lewis Acids and Bases: A Lewis acid is a substance that can accept an electron pair, whereas a Lewis base can donate an electron pair. Importantly, while all Brønsted acids are also Lewis acids, the reverse is not true. [9] Lewis acid sites in zeolites can include extra-framework aluminum species or introduced metal cations. [10]

- Reaction Mechanisms: The type of acid site dictates the reaction initiation mechanism. An olefin can form a carbenium ion by reacting with a proton from a Brønsted acid site. Conversely, an alkane can form the same carbenium ion by donating a hydride ion (H⁻) to a Lewis acid site. [7]

The diagram below illustrates the hierarchical relationship between these acid theories and the initiation of carbocation formation on solid catalysts.

Comparative Analysis of H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta Zeolites

H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta are medium and large-pore zeolites, respectively, with distinct structural and acidic properties that dictate their application.

Structural and Acidity Characteristics

The table below summarizes the fundamental properties of H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta zeolites.

Table 1: Structural and General Acidity Properties of H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta

| Property | H-ZSM-5 | H-Beta | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pore System | 3D, medium-pore | 3D, large-pore | H-Beta's larger pores facilitate diffusion of bulkier molecules. [11] |

| Channel Dimensions | 10-membered rings (~5.5 Å) | 12-membered rings (~7.0 Å x 6.0 Å) | |

| Typical Si/Al Range | 10 - ∞ | 5 - ∞ | A lower Si/Al ratio generally implies a higher density of Brønsted acid sites. |

| Brønsted Acid Site Origin | Framework Al in T-sites | Framework Al in T-sites | Strength and density depend on Al distribution in the framework. [12] [13] |

| Common Lewis Acid Sites | Extra-framework Al, Sn cations | Extra-framework Al | Sn-Lewis sites in H-ZSM-5 are primarily located at channel intersections. [10] |

Quantitative Acidity and Performance Data

Experimental data from catalytic pyrolysis of low-density polyethylene (LDPE) provides a direct comparison of the performance of these zeolites.

Table 2: Catalytic Performance of Zeolites in LDPE Pyrolysis for Aromatics Production [11]

| Catalyst | Pore Size | Relative Acid Site Concentration | Liquid Yield (wt%) | Main Aromatic Products | Selectivity for MAHs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H-ZSM-5 | Medium | High | 25.71% | BTX (Benzene, Toluene, Xylenes) | Very High |

| H-Beta | Large | Medium | 33.08% | Heavier Aromatics (C9-C13) | Moderate |

| HY | Large | Low | 41.11% | Waxes, Alkanes, Alkenes | Low |

| MCM-41 | Very Large | Very Low | 7.11% | Waxes, Alkanes, Alkenes | Very Low |

Key Performance Insights:

- H-ZSM-5 exhibits superior shape selectivity due to its medium pore size, effectively cracking polyethylene into valuable monocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (MAHs) like BTX. Its high acid strength and confined pore structure favor these reactions. [11]

- H-Beta, with its larger pores, allows for the formation and diffusion of larger aromatic molecules (C9-C13). While it produces a higher liquid yield than H-ZSM-5, its selectivity for the most desirable MAHs is lower. [11]

- The data underscores that a higher concentration of strong acid sites (as in H-ZSM-5) is more critical for selective aromatics production than pore size alone.

Essential Techniques for Acidity Quantification

Accurately measuring the number, strength, and type of acid sites is crucial for catalyst characterization. The following workflow outlines a multi-technique approach for comprehensive acidity assessment.

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

Ammonia Temperature-Programmed Desorption (NH₃-TPD)

Purpose: To quantify the total acid site density and profile the acid strength distribution.

Detailed Protocol: [13]

- Pre-treatment: Place ~0.1 g of catalyst in a quartz tube reactor. Dry the sample at 623 K (350 °C) for 1 hour under a flowing inert gas (e.g., Helium at 15-50 mL/min) to remove water and contaminants.

- Saturation: Cool the sample to 373 K (100 °C). Switch the flow to a gas mixture containing 10% ammonia in helium for 30-60 minutes to ensure complete saturation of acid sites.

- Physisorbed NH₃ Removal: Flush with pure helium at the same temperature for 30-60 minutes to remove weakly physisorbed ammonia from the catalyst surface and pores.

- Desorption: Heat the sample in a helium flow (e.g., 10 K/min ramp) from 373 K to 873 K (600 °C). Monitor the desorbed ammonia using a thermal conductivity detector (TCD).

- Data Analysis: The temperature of the desorption peak indicates acid strength (low vs. high temperature), while the area under the curve is proportional to the total number of acid sites.

Probe Molecule Infrared Spectroscopy (IR)

Purpose: To distinguish between Brønsted and Lewis acid sites.

Detailed Protocol (using Pyridine): [13]

- Sample Preparation: Press the zeolite powder into a self-supporting wafer and load it into an IR cell.

- Pre-treatment: Activate the wafer under vacuum (~10⁻⁵ mbar) at 723 K (450 °C) for 1-2 hours to clean the surface.

- Probe Adsorption: Expose the wafer to pyridine vapor at room temperature, then heat to ~423 K (150 °C) under vacuum to remove physisorbed species.

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect the IR spectrum. The band at ~1545 cm⁻¹ is characteristic of pyridine bound to Brønsted acid sites (pyridinium ion), while the band at ~1450 cm⁻¹ is indicative of pyridine coordinated to Lewis acid sites. The concentration of each site type can be calculated using the Beer-Lambert law and established molar extinction coefficients.

Inelastic Neutron Scattering (INS)

Purpose: To directly quantify and differentiate between various types of hydroxyl groups, providing a direct count of Brønsted acid protons.

Detailed Protocol: [13]

- Deuteration: A sample is treated with heavy water (D₂O) at elevated temperatures (e.g., 573 K) to exchange Brønsted acid sites (Si-OH-Al) with deuterium (Si-OD-Al).

- INS Measurement: INS spectra are collected for both the protonated and deuterated samples at very low temperatures (<20 K) to minimize thermal effects.

- Data Analysis: The difference in spectra allows for the direct identification and quantification of different hydroxyl groups, such as Brønsted acid sites, silanol groups (Si-OH), and hydroxyls on extra-framework aluminum. This technique confirmed that in a commercial H-ZSM-5, only about 50% of the total aluminum content formed active Brønsted acid sites, with the rest existing as extra-framework species. [13]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Acidity Quantification

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Ammonia (NH₃, 10% in He) | A basic probe molecule that adsorbs on both Brønsted and Lewis acid sites. | Used in NH₃-TPD to measure total acid site density and strength distribution. [13] |

| Pyridine (C₅H₅N) | A spectroscopic probe molecule that produces distinct IR fingerprints when bound to Brønsted or Lewis sites. | Used in Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy (DRIFTS) to quantify B/L ratios. [13] |

| Deuterated Water (D₂O) | Used for isotopic exchange of Brønsted acid protons. | Essential for INS spectroscopy to differentiate between types of hydroxyl groups via H/D exchange. [13] |

| Trimethylamine (N(CH₃)₃) | A strong Lewis base used in computational and experimental studies to assess Lewis acidity. | Used in theoretical calculations to compute electron transfer parameters correlating with Lewis acid strength. [14] |

| Zeolite H-ZSM-5 / H-Beta | The solid acid catalysts under investigation. | Commercial powders are typically calcined at 773-823 K in air before use to remove organic templates. [13] [11] |

The strategic selection between H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta catalysts hinges on a detailed understanding of their acid site density and distribution. H-ZSM-5, with its high concentration of strong Brønsted acid sites and shape-selective medium pores, is the superior catalyst for reactions demanding high selectivity to light aromatics like BTX. In contrast, H-Beta's larger pore structure accommodates reactions involving bulkier molecules but generally yields a broader, less selective product slate. A robust characterization strategy, combining quantitative techniques like NH₃-TPD with speciation methods like pyridine-IR, is indispensable for linking these fundamental acidic properties to catalytic performance. This guide provides the foundational protocols and data to empower researchers in making these critical distinctions for catalyst design and application.

Influence of Si/Al Ratio on Acidity and Thermal Stability

The strategic selection and optimization of zeolite catalysts are fundamental to advancing efficiency and sustainability in numerous industrial processes, from petroleum refining to pharmaceutical development. Among the critical parameters governing zeolite performance, the framework Si/Al ratio stands out for its profound influence on both acidity and thermal stability. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of two prominent zeolite catalysts, H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta, focusing on how the Si/Al ratio modulates their properties and, consequently, their performance in key applications. The analysis is framed within the context of catalytic cracking for light olefin production, a critical reaction pathway in the petrochemical industry, with insights relevant to researchers and scientists across fields.

Acidity and Catalytic Performance

The Si/Al ratio directly determines the concentration of Brønsted acid sites in the zeolite framework, as each aluminum atom introduces a proton for charge balance. This ratio also indirectly influences acid site strength and distribution, which are pivotal for catalytic activity and selectivity.

Acidity Characteristics of H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta

- H-ZSM-5 (MFI Framework): This zeolite possesses a three-dimensional network of medium-sized pores (10-membered rings, ~5.5 Å). Its acidity is characterized by strong Brønsted acid sites. A key feature of H-ZSM-5 is that its Al atoms are typically isolated; the formation of Al-O-(Si-O)n>-Al pairs with n=2 (next-next nearest-neighbors) is possible and can influence selectivity, but closer associations (Al-O-Si-O-Al) are generally absent [15]. The strength of individual Brønsted sites shows less variation with Si/Al ratio, with the primary effect being a change in the total number of active sites [15].

- H-Beta (*BEA Framework): This large-pore zeolite features a three-dimensional system of 12-membered ring channels (~6.5 Å). The distribution of Al atoms in its framework is not random, with certain T-sites (e.g., T7 and T9) being preferentially occupied, and this distribution is sensitive to both the Si/Al ratio and synthesis temperature [16]. The strength of its Brønsted acid sites has been shown to be comparable to, though potentially slightly lower than, that of H-ZSM-5 [17].

Table 1: Comparative Acidity and Performance in Model Reactions

| Feature | H-ZSM-5 | H-Beta |

|---|---|---|

| Pore System | 10-MR, medium pore (~5.5 Å) [15] | 12-MR, large pore (~6.5 Å) [18] [17] |

| Typical Si/Al Range in Studies | 20 to >300 [19] [15] | 19 to 360 [18] [20] |

| Acid Site Density | Higher at low Si/Al ratios, decreases as Si/Al increases | Higher at low Si/Al ratios, decreases as Si/Al increases |

| n-Hexane Cracking (Light Olefin Yield) | ~52.5% selectivity (ZSM-12, Si/Al=80) [19] | — |

| n-Dodecane Cracking (Light Olefin Yield) | ~45-47.8% [20] | Up to 74.3% in SCC (Si/Al=300) [20] |

| Propylene/Ethylene (P/E) Ratio | Can be tuned (e.g., 1.75 for ZSM-12) [19] | Higher selectivity to propylene possible [21] |

| Impact of High Si/Al | Increased shape selectivity, reduced coking [19] | Enhanced hydrophobicity, higher diffusion rates [21] |

Catalytic Performance in Hydrocarbon Cracking

The differential performance of H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta is clearly illustrated in the catalytic cracking of hydrocarbons, a vital reaction for light olefin production.

Reaction Pathways and Selectivity: The medium pores of H-ZSM-5 impose significant shape selectivity, favoring monomolecular cracking pathways that are conducive to producing ethylene and propylene. In contrast, the larger pores of H-Beta facilitate bimolecular reactions, such as hydrogen transfer, which can lead to higher yields of propylene and aromatics [21] [20]. For instance, in the catalytic cracking of n-hexane, a ZSM-12 zeolite (structurally similar to ZSM-5) with an optimal Si/Al ratio of 80 achieved a light olefin yield of 52.5% and a high P/E ratio of 1.75 [19].

Influence of Si/Al Ratio: The Si/Al ratio is a powerful tool to steer product distribution.

- In H-ZSM-5, a higher Si/Al ratio reduces the density of acid sites, which in turn suppresses undesired hydrogen transfer and aromatization reactions that lead to coke formation, thereby improving catalyst lifetime [19] [15].

- In H-Beta, optimizing the Si/Al ratio is critical for maximizing light olefin yield. In the steam catalytic cracking (SCC) of n-dodecane, a model compound for diesel and kerosene, H-Beta with a very high Si/Al ratio of 300 yielded an exceptional 74.3% light olefins [20]. This is attributed to the optimal balance of acid site density and enhanced diffusion properties in a highly siliceous framework.

The following diagram summarizes the logical relationship between the Si/Al ratio and the resulting catalyst properties.

Figure 1: Logical impact of the Si/Al ratio on zeolite catalyst properties. An increasing Si/Al ratio directly enhances stability and hydrophobicity while reducing acid site density, which collectively optimizes light olefin yield and selectivity.

Thermal and Hydrothermal Stability

Thermal stability is a cornerstone of catalyst durability, especially in processes involving high temperatures or steam. The Si/Al ratio is a primary determinant of a zeolite's resilience.

Structural Stability and Dealumination

- H-ZSM-5: The H-ZSM-5 framework is renowned for its high thermal stability. This robustness stems from its silica-rich nature, which allows it to maintain structural integrity even at very high Si/Al ratios. Dealumination—the removal of aluminum from the framework—can occur under severe conditions, but the framework often remains stable [22].

- H-Beta: The thermal stability of H-Beta is more directly and strongly influenced by its Si/Al ratio. First-principles studies show that dealumination energy varies significantly with the specific framework T-site, with sites T7 and T9 being more prone to dealumination than T1 and T2 [16]. This implies that the stability of a given H-Beta catalyst depends not only on the overall Si/Al ratio but also on the specific distribution of Al atoms within its framework. Lower Si/Al ratios (Al-rich frameworks) generally lead to lower stability due to the higher density of less stable Al-O bonds [22].

Table 2: Comparative Thermal Stability Indicators

| Aspect | H-ZSM-5 | H-Beta |

|---|---|---|

| Inherent Thermal Stability | High [22] | Good, but more dependent on Si/Al [22] |

| Hydrothermal Stability | Moderate to High | Can be optimized via dealumination (e.g., USY) [22] |

| Key Stabilizing Factor | High silica content, robust MFI framework [22] | High Si/Al ratio, specific Al siting (e.g., T1, T2 sites) [16] |

| Dealumination Tendency | Occurs under severe conditions | T7 and T9 sites are more susceptible [16] |

| Effect of Low Si/Al | Reduced stability, lower phase transition temperature [15] | Markedly reduced stability [22] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure the reproducibility of catalyst performance data, understanding the standard experimental protocols for synthesizing, characterizing, and testing these zeolites is essential.

Catalyst Synthesis and Modification

A common method for synthesizing both H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta zeolites with targeted Si/Al ratios is hydrothermal synthesis [21] [19]. A typical procedure involves:

- Gel Preparation: Preparing a precursor solution containing a silica source (e.g., colloidal silica), an aluminum source (e.g., sodium aluminate), an organic structure-directing agent (OSDA, e.g., tetraethylammonium hydroxide for Beta, tetrapropylammonium for ZSM-5), and a mineralizer (e.g., NaOH) in deionized water [21] [19].

- Crystallization: Transferring the mixture to an autoclave and crystallizing it at a specific temperature (e.g., 145-180 °C) for a defined period (e.g., 48-120 hours) [21] [19].

- Post-treatment: Washing, drying, and calcining the resulting powder to remove the OSDA. This is often followed by ion exchange with an ammonium salt (e.g., NH₄NO₃) and a final calcination to produce the protonated (H-) form of the zeolite [19].

The Si/Al ratio of the final product can be controlled by adjusting the Si/Al ratio in the initial gel composition [22]. Post-synthetic modifications like dealumination (e.g., via steam treatment) or desilication (with alkali solutions) can also be used to fine-tune the ratio and introduce mesoporosity [22] [20].

Core Characterization Techniques

- Acidity Measurement (NH₃-TPD): Temperature-Programmed Desorption of Ammonia (NH₃-TPD) is a standard method to quantify acid site density and strength. The catalyst is saturated with ammonia, and then the temperature is raised linearly while the desorbed ammonia is monitored, providing a profile of acid site strength distribution [19] [20].

- Framework Analysis (XRD): X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) is used to confirm the crystalline structure of the zeolite, identify impurity phases, and monitor changes in unit cell parameters that may occur with varying Si/Al ratio [21] [19] [15].

- Elemental Composition (ICP-AES): Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-AES) is employed to accurately determine the bulk Si/Al ratio of the synthesized zeolites [19].

- Porosity Analysis (BET): Nitrogen adsorption-desorption at 77 K is used to determine surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution using the BET (Brunauer-Emmett-Teller) and BJH (Barrett-Joyner-Halenda) methods [21] [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This table details key materials and reagents used in the zeolite research cited within this guide, along with their common functions.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Zeolite Synthesis and Testing

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Source |

|---|---|---|

| Tetraethylammonium Hydroxide (TEAOH) | Organic Structure-Directing Agent (OSDA) for Beta zeolite synthesis [21] | Sigma-Aldrich [21] |

| Tetrapropylammonium Bromide (TPABr) | OSDA for ZSM-5 synthesis [19] | Merck [19] |

| Colloidal Silica | Silica source for framework construction [21] [19] | Merck [19], Junsei Chemical [20] |

| Sodium Aluminate | Aluminum source for framework construction [21] | Nanochemazone [21], Junsei Chemical [20] |

| Ammonium Nitrate | For ion exchange to convert zeolite to active H-form [21] [19] | Sigma-Aldrich [21], Junsei Chemical [20] |

| n-Hexane / n-Dodecane | Model hydrocarbon feed for catalytic cracking tests [19] [20] | -- |

The optimal choice between H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta is not a matter of superiority but of application-specific suitability. The Si/Al ratio serves as a powerful and versatile design parameter for both.

- H-ZSM-5 excels in applications requiring strong shape selectivity and high thermal resilience, particularly for converting smaller hydrocarbon feeds. Its performance is optimized by using a high Si/Al ratio to minimize coking and enhance stability.

- H-Beta is the preferred candidate for processing larger molecules, where its substantial pore size offers a critical advantage. Its acidity and stability are more sensitive to the Si/Al ratio, requiring precise optimization, as demonstrated by the exceptional light olefin yields achieved with highly siliceous H-Beta in cracking heavy model feeds.

For researchers, the pathway to catalyst optimization is clear: a systematic investigation of the Si/Al ratio, combined with advanced characterization and testing, is essential to tailor the properties of H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta for peak performance in any given process.

Textural properties, including surface area, microporosity, and mesoporosity, are fundamental determinants of zeolite catalytic performance. These characteristics govern mass transfer efficiency, accessibility of active sites, and ultimately influence reaction kinetics, product selectivity, and catalyst longevity. Within the context of catalyst selection for research and industrial applications, understanding how these properties vary between common zeolite frameworks is crucial. This guide provides an objective comparison of two prominent zeolite catalysts—H-ZSM-5 (with MFI topology) and H-Beta (with *BEA topology)—synthesizing experimental data to elucidate how their distinct textural properties influence functionality in various catalytic processes.

Fundamental Structural Comparison

H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta possess fundamentally different pore architectures that define their respective textural properties and catalytic applications.

H-ZSM-5 features a two-dimensional pore system consisting of straight channels (5.4 × 5.6 Å) running along the b-axis and sinusoidal channels (5.1 × 5.4 Å) parallel to the a-axis [2]. This medium-pore zeolite has a pore structure formed by 10-membered oxygen rings.

H-Beta has a three-dimensional, interconnected channel system with larger 12-membered rings, creating two straight channel types (0.55 × 0.55 nm and 0.76 × 0.64 nm) [23]. This large-pore zeolite possesses a higher inherent pore volume but is more susceptible to diffusion limitations with bulky molecules despite its larger pore dimensions.

The following diagram illustrates the hierarchical structures and strategic site management in these zeolites:

Textural Properties and Modification Techniques

Porosity and Surface Area Characteristics

Table 1: Native Textural Properties of H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta Zeolites

| Property | H-ZSM-5 (MFI) | H-Beta (*BEA) | Experimental Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Channel Dimensionality | 2D | 3D | X-ray Diffraction [24] [23] |

| Pore Size | 5.1-5.6 Å (10-MR) | 5.5-7.6 Å (12-MR) | Structural Analysis [23] [2] |

| Typical Micropore Volume | ~0.15-0.18 cm³/g | ~0.20-0.22 cm³/g | N₂ Physisorption [25] |

| Framework Stability | High in alkaline solutions | Lower in alkaline solutions | Alkaline Treatment [23] [26] |

| Optimal Si/Al for Modification | 25-50 [26] | Framework-dependent | Compositional Analysis [26] |

Hierarchization Methods and Outcomes

Both zeolites benefit from the introduction of mesoporosity to overcome diffusion limitations, though their structural differences necessitate distinct optimization approaches.

H-ZSM-5 demonstrates robust stability during desilication using NaOH solutions, with an optimal Si/Al range of 25-50 for effective mesopore generation without excessive framework damage [26]. The introduction of mesoporosity (approximately 8.6 nm average diameter) via post-synthetic treatment creates a fivefold increase in mesopore volume while preserving 80.6% relative crystallinity and comparable micropore volume [25]. This hierarchical structure significantly improves conversion and yield in Friedel-Crafts alkylation of toluene with ethene [24].

H-Beta requires modified hierarchization approaches due to its lower stability in alkaline solutions [23] [26]. Successful methods include:

- NH₄F treatment: Simultaneously removes silicon and aluminum, preserving the original Si/Al ratio and acidity [23]

- Protected desilication: Using pore-directing agents (PDAs) like tetraalkylammonium hydroxides to reduce surface exposure during NaOH treatment [23]

- Controlled conditions: Low temperatures (65-80°C) and short treatment durations (30 minutes) to preserve crystallinity [23]

Table 2: Hierarchization Agent Efficacy Comparison

| Modification Agent | Mesoporosity Generation | Acidity Preservation | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| NaOH (H-ZSM-5) | High | Moderate | Stable frameworks with optimal Si/Al [24] [26] |

| NaOH (H-Beta) | High | Lower | Requires protective agents [23] [26] |

| NH₄F | Moderate | High | Acid-sensitive reactions [23] |

| NH₄OH | Moderate | High | Beta zeolite preservation [23] |

| TAAOH with NaOH | Tunable | Moderate to High | Tailoring mesopore size [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Textural Characterization

Mesopore Generation via Alkaline Treatment

Objective: Introduce intracrystalline mesoporosity while preserving microporous framework integrity.

Materials:

- Parent zeolite (H-ZSM-5 or H-Beta)

- Alkaline solution (NaOH, NH₄OH, or TAAOH)

- Heating apparatus with temperature control

- Centrifuge and washing equipment

Procedure:

- Prepare a 0.2 M solution of the selected alkaline agent [23] [26]

- Suspend zeolite in the solution at a ratio of 1:30 solid:liquid (w/v) [26]

- Heat the mixture to 65°C with continuous stirring for 30 minutes [23] [26]

- Quench the reaction by rapid cooling and centrifugation

- Wash the solid product repeatedly with deionized water until neutral pH

- Dry at 100°C overnight and calcine at 550°C for 5 hours (if ammonium forms are used)

Critical Parameters:

- Si/Al ratio: Must be within optimal range (25-50 for H-ZSM-5) [26]

- Temperature control: Critical for Beta zeolite to prevent framework collapse [23]

- Treatment duration: Shorter times (0.5-2 hours) preserve crystallinity [23]

Acidity Measurement by DRIFT-FTIR Spectroscopy

Objective: Quantify Brønsted and Lewis acid site concentrations before and after modification.

Materials:

- FTIR spectrometer with diffuse reflectance attachment

- High-temperature reaction chamber

- Probe molecules (pyridine, ammonia)

Procedure:

- Activate zeolite sample at 400°C under vacuum for 1 hour

- Cool to room temperature and collect background spectrum

- Expose to probe molecule vapor (saturate)

- Physiosorbed molecules by heating at 150°C for 30 minutes

- Collect spectrum in the 1400-1700 cm⁻¹ range for pyridine

- Calculate acid site concentrations using extinction coefficients

Data Interpretation:

- Brønsted acid sites: ~1545 cm⁻¹ [2]

- Lewis acid sites: ~1450 cm⁻¹

- Total acidity: Combination of both sites

Catalytic Performance in Model Reactions

Friedel-Crafts Alkylation of Toluene with Ethene

H-ZSM-5 catalysts with introduced mesoporosity demonstrate superior performance in Friedel-Crafts alkylation:

- Conversion increase: Mesoporous H-ZSM-5 shows higher toluene conversion compared to purely microporous counterpart [24]

- Yield enhancement: Higher product yield (C9) obtained with hierarchical catalyst [24]

- Selectivity preservation: Minimal effects on mono- vs. dialkylation selectivity and ortho:meta:para ratio [24]

The experimental workflow for evaluating catalytic performance typically follows this pathway:

Esterification of Acetic Acid with Different Alcohols

Hierarchical H-Beta catalysts show size-dependent performance in esterification reactions:

- Small molecules (methanol): Activity depends primarily on acidity [23]

- Large molecules (n-butanol, benzyl alcohol): Activity influenced by both acidity and mesoporosity [23]

- Optimized systems: NH₄F-modified H-Beta, with lower mesoporosity but higher acidity, exhibited better performance with larger alcohols [23]

Hydrodeoxygenation of Fatty Acids

Spatially segregated hierarchical H-ZSM-5 catalysts demonstrate remarkable efficiency in biofuel applications:

- Activity enhancement: 30.6 vs 3.6 mol dodecane molPd⁻¹ h⁻¹ compared to conventional catalyst [25]

- Selectivity improvement: C12:C11 ratio of 5.2 vs 1.9 [25]

- Mechanism: Spatial segregation of Pd nanoparticles (in mesopores) and acid sites (in micropores) reduces undesirable side reactions [25]

Table 3: Catalytic Performance Comparison in Model Reactions

| Reaction | Optimal Catalyst | Key Performance Advantage | Structural Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Friedel-Crafts Alkylation | Mesoporous H-ZSM-5 | Higher conversion and yield | Enhanced diffusion without selectivity loss [24] |

| Esterification (Large Alcohols) | NH₄F-Modified H-Beta | Balanced acidity and accessibility | Preserved acidity with moderate mesoporosity [23] |

| Fatty Acid HDO | Spatially Segregated H-ZSM-5 | Enhanced activity/selectivity | Compartmentalization of catalytic sites [25] |

| Olefin Cracking | Morphology-Controlled H-ZSM-5 | Improved activity and stability | Diffusion anisotropy optimization [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Zeolite Modification and Characterization

| Reagent/Chemical | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| NaOH | Desilication agent | Mesopore generation in stable zeolites (H-ZSM-5) [24] [26] |

| NH₄F | Mild etching agent | Hierarchization with acidity preservation (H-Beta) [23] |

| Tetraalkylammonium Hydroxides | Pore-directing agents | Controlled mesopore size development [26] |

| Oxalic Acid | Dealumination agent | Pre-treatment for Si/Al ratio adjustment [26] |

| Cationic Polymers | Soft templates | Direct synthesis of hierarchical structures [24] |

| Pre-formed Pd Nanoparticles | Metal functionalization | Selective deposition in mesopores for cascade reactions [25] |

The comparative analysis of H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta textural properties reveals a fundamental trade-off in zeolite catalyst design. H-ZSM-5 offers superior framework stability for aggressive modifications and demonstrates exceptional performance in reactions requiring shape selectivity and controlled acidity. H-Beta provides larger innate pore dimensions beneficial for processing bulky molecules but requires more careful hierarchization approaches to preserve its structural integrity.

The optimal catalyst selection depends critically on the specific reaction requirements: H-ZSM-5 variants excel in hydrocarbon transformations and cascade reactions where site segregation is beneficial, while hierarchical H-Beta materials offer advantages in processing larger molecules when appropriate modification protocols are employed. Future catalyst development should focus on reaction-specific optimization of hierarchical structures, leveraging the distinct textural advantages of each framework type while mitigating their inherent limitations through advanced modification techniques.

Catalysts in Action: Performance in Key Reactions and Process Applications

The methylation of benzene with methanol is a critical reaction in the methanol-to-hydrocarbons (MTH) process, a prominent alternative to crude-oil cracking for the production of light olefins and other valuable chemicals. The kinetics of this elementary step are highly influenced by the catalyst's topology and acidity. This guide provides a direct comparison of two industrially relevant zeolite catalysts, H-ZSM-5 and H-beta, focusing on their performance in benzene methylation. We objectively summarize experimental kinetic data and provide detailed methodologies to aid researchers in catalyst selection and fundamental understanding.

Catalyst Comparison: H-ZSM-5 vs. H-Beta

Structural and Acidity Properties

The performance of a zeolite catalyst is governed by its structural and acidic characteristics. The table below summarizes the key properties of H-ZSM-5 and H-beta relevant to benzene methylation.

Table 1: Structural and Acidity Properties of H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta Catalysts

| Property | H-ZSM-5 (MFI) | H-Beta (BEA) |

|---|---|---|

| Pore Structure | 3D; intersecting medium-pore channels | 3D; intersecting large-pore channels |

| Channel Dimensions | Sinusoidal: 0.51 nm × 0.55 nmStraight: 0.53 nm × 0.56 nm [27] | Straight: 0.75 nm × 0.57 nmSinusoidal: 0.65 nm × 0.56 nm [27] |

| Typical Acidity (from characterized samples) | Strong Brønsted acidity | Strong Brønsted acidity [27] |

| Confinement Effect | Optimal host-guest interactions [5] [28] | Less confined environment [5] |

Experimental Kinetic Performance

Kinetic studies performed at 350 °C reveal significant differences in catalyst activity. The following table consolidates quantitative kinetic data for direct comparison.

Table 2: Experimental Kinetic Parameters for Benzene Methylation at 350°C [5]

| Kinetic Parameter | H-ZSM-5 | H-Beta |

|---|---|---|

| First-Order Rate Constant, k (m³·kg⁻¹·s⁻¹) | 1.9 × 10⁻⁶ | 4.6 × 10⁻⁷ |

| Apparent Activation Energy, Eₐ (kJ·mol⁻¹) | 99 | 109 |

| Reaction Order in Benzene | ~1 | ~1 |

| Reaction Order in Methanol | ~0 | ~0 |

| Relative Methylation Rate | Consistently higher [28] | Consistently lower |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and clarity, this section outlines the key experimental methodologies from the cited studies.

Catalyst Preparation and Characterization

The kinetic comparison relies on well-characterized H-ZSM-5 and H-beta catalysts with similar acid site densities and crystallite sizes to isolate the effect of topology [5].

- Synthesis & Preparation: The H-ZSM-5 catalyst was obtained commercially. The H-beta catalyst was synthesized in-house via a hydrothermal method. This involved homogenizing silica (Degussa Aerosil 380) into a 20% aqueous solution of tetraethylammonium hydroxide, adding sodium aluminate and NaOH, and crystallizing the gel in an autoclave. The resulting solid was calcined to remove the template [5].

- Characterization Techniques:

- X-Ray Diffraction (XRD): Used to confirm the high crystallinity of both catalyst samples.

- BET Surface Area Analysis: Determined the specific surface area, indicative of high-quality, crystalline materials.

- ²⁷Al MAS-NMR: Verified that the aluminum was predominantly in a tetrahedral framework coordination, confirming the quality of the Brønsted acid sites.

- NH₃-TPD (Ammonia Temperature-Programmed Desorption): A common technique for quantifying acid site concentration and strength.

Kinetic Measurement Setup

The kinetic measurements were designed to isolate the benzene methylation reaction from secondary reactions.

- Reactor System: Experiments were performed in a setup utilizing very high feed rates to achieve low conversion, thereby suppressing side reactions and allowing direct monitoring of the methylation rate [5].

- Standard Procedure:

- Catalyst Loading: The zeolite catalyst is loaded into the reactor.

- Pre-treatment: The catalyst is typically activated in-situ under an inert gas flow at elevated temperature to remove water and other adsorbates.

- Reaction Feed: A vaporized feed mixture of benzene and methanol in a carrier gas (e.g., nitrogen or argon) is passed through the catalyst bed at a controlled, high flow rate.

- Product Analysis: The effluent stream is analyzed using online Gas Chromatography (GC) to separate and quantify the reactants and products, primarily benzene, methanol, and toluene.

- Data Analysis: The methylation rate is determined from the conversion of benzene to toluene. Kinetic parameters like rate constants and reaction orders are extracted by varying feed concentrations and reactor temperature [5].

Reaction Mechanism and Visualization

The Concerted Methylation Mechanism

While two mechanistic pathways (stepwise and concerted) have been proposed, experimental kinetic data for benzene methylation are readily explained by a concerted mechanism [5]. In this mechanism, a physisorbed methanol molecule directly interacts with a benzene molecule in a single kinetic step, rather than proceeding through a stable surface-bound methoxy intermediate.

Figure 1: Catalytic Cycle for Concerted Benzene Methylation. The mechanism involves a direct reaction between adsorbed methanol and benzene, leading to a toluenium ion and water, followed by catalyst regeneration.

The Origin of Selectivity: Confinement Effects

The higher methylation rate observed on H-ZSM-5 is attributed to its pore topology. Theoretical simulations indicate that the medium pores of H-ZSM-5 provide optimal confinement for the reacting species. The more favorable host-guest interactions in H-ZSM-5's tighter channels stabilize the reaction intermediates and transition state, an effect that outweighs the greater entropy loss upon benzene adsorption compared to the larger-pore H-beta [5] [28].

Figure 2: Influence of Zeolite Topology on Methylation Kinetics. The superior performance of H-ZSM-5 is primarily due to pore confinement effects that stabilize the reacting species, outweighing entropy considerations.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| H-ZSM-5 Zeolite | MFI-topology catalyst with medium pores and strong Brønsted acidity; the benchmark for many acid-catalyzed reactions. |

| H-Beta Zeolite | BEA-topology catalyst with large pores and strong Brønsted acidity; suitable for reactions involving larger molecules [27]. |

| Methanol & Benzene | High-purity reactant feeds. Methanol acts as the methylating agent, while benzene is the aromatic core. |

| Gas Chromatograph (GC) | Essential analytical instrument for separating and quantifying reaction products (e.g., toluene, unreacted benzene/methanol). |

| Tube Furnace / Reactor | Provides controlled high-temperature environment for conducting vapor-phase catalytic reactions. |

| In-situ Cell / DRIFTS | Allows for characterization of adsorbed species and reaction intermediates under operational conditions [29]. |

Zeolite catalysts are pivotal in the conversion of renewable alcohols into high-value hydrocarbons, serving as sustainable pathways for fuel and chemical production. Among the various zeolites investigated, H-ZSM-5 (MFI topology) and H-Beta (BEA topology) have emerged as prominent catalysts for methanol-to-hydrocarbons (MTH) and ethanol-to-aromatics (ETA) processes. Understanding their comparative efficacy is essential for rational catalyst selection and process optimization. This guide provides a systematic comparison of H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta performance, drawing upon experimental data and mechanistic insights to inform researchers and development professionals in the field of catalytic reaction engineering.

The fundamental differences in pore architecture, acidity, and diffusion characteristics between these zeolites dictate their application-specific performance. While both catalysts possess three-dimensional pore systems, their structural distinctions lead to marked variations in product distribution, catalyst stability, and preferential conversion pathways. This analysis synthesizes current research to objectively evaluate their respective advantages and limitations within the context of alcohol-to-hydrocarbon conversion.

Structural and Acidic Properties Comparison

The catalytic performance of H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta zeolites is fundamentally governed by their distinct structural characteristics and acidic properties, which are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Structural and acidic properties of H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta zeolites

| Property | H-ZSM-5 | H-Beta | Impact on Catalysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pore Topology | 3D intersecting 10-membered rings (MR) [2] | 3D intersecting 12-membered rings (MR) [30] | H-Beta allows access/diffusion of larger molecules |

| Channel Dimensions | Straight: 5.4 × 5.6 Å; Sinusoidal: 5.1 × 5.4 Å [2] | 0.56 × 0.56 nm and 0.66 × 0.67 nm [30] | H-Beta experiences lower diffusion restrictions |

| Pore Size Classification | Medium-pore | Large-pore | H-Beta more prone to coking from bulky species |

| Typical Acidity (Brønsted) | Strong, tunable Si/Al ratio | Strong, but more susceptible to dealumination | Both provide sufficient acid strength for reactions |

| Diffusion Characteristics | Anisotropic, shape-selective [2] | Less restricted, superior mass transfer [31] | H-ZSM-5 offers superior shape selectivity |

The medium-pore architecture of H-ZSM-5 imposes significant diffusion limitations for bulky molecules but confers excellent shape selectivity and reduces deactivation rates in certain processes. In contrast, the large-pore system of H-Beta enables superior mass transfer of reactants and products, which is beneficial for converting larger feed molecules, though this comes at the cost of accelerated coking from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and other coke precursors [5] [31].

Catalytic Performance in MTH and ETA Reactions

The structural differences between H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta translate into distinct catalytic performances in alcohol conversion processes, as quantified by experimental studies summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Comparative catalytic performance of H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta in MTH and ETA reactions

| Reaction Process | Catalyst | Key Performance Metrics | Experimental Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzene Methylation | H-ZSM-5 | Higher methylation rate than H-Beta [5] | Low conversion, high feed rates [5] | [5] |

| Methanol-to-Olefins (MTO) | H-ZSM-5 | Main products: short olefins (ethylene, propylene) [32] | Not specified in detail [32] | [32] |

| Ethanol-to-Aromatics (ETA) | H-ZSM-5 | Larger olefins and aromatics dominate products [32] | Not specified in detail [32] | [32] |

| Catalytic Fast Pyrolysis | H-ZSM-5 | Highest selectivity to aromatic hydrocarbons (31.6%) [33] | Pyroprobe micro-reactor, GC/MS [33] | [33] |

| Transalkylation of Heavy Reformate | H-Beta | Better activity and selectivity to xylenes [30] | Fixed-bed reactor [30] | [30] |

Performance in Methanol-to-Hydrocarbons (MTH)

The MTH process encompasses several technology variants, including methanol-to-olefins (MTO) and methanol-to-gasoline (MTG). For MTO applications, H-ZSM-5 produces a product stream rich in short-chain olefins, particularly ethylene and propylene [32]. This selectivity stems from its medium-pore structure, which imposes shape-selective constraints that favor the formation and egress of lighter olefins.

In direct comparisons for benzene methylation with methanol—a key step in the hydrocarbon pool mechanism—H-ZSM-5 demonstrates a consistently higher methylation rate than H-Beta. A combined experimental-theoretical study attributed this enhanced activity to more favorable host-guest interactions within the H-ZSM-5 pores, which outweigh the greater loss of entropy compared to H-Beta [5]. Furthermore, H-Beta suffers from rapid deactivation through coke formation during MTH conversion, rendering it less suitable for industrial applications despite its high initial activity [5].

Performance in Ethanol-to-Aromatics (ETA)

In the ETA process, the inherent C-C bond in ethanol leads to a different conversion mechanism compared to methanol. Upon dehydration, ethanol readily forms ethylene, which subsequently undergoes oligomerization to form larger hydrocarbons [32]. When comparing the two zeolites for ETA conversion, larger olefins and aromatics dominate the product distribution over both catalysts [32].

The influence of crystal size differs significantly between MTO and ETA processes. For ETA conversion, the instantly available aromatics lead to fast coking, rendering only the outer layers of the zeolite crystals active. This diminishes the effectiveness of the catalyst's interior, making the benefit of reduced crystal size less pronounced than in MTO conversion [32].

Reaction Mechanisms and Pathways

The conversion of methanol and ethanol over acidic zeolites proceeds through complex mechanistic pathways that share common elements but differ in key aspects, largely influenced by the presence of an initial C-C bond in ethanol.

Methanol-to-Hydrocarbons (MTH) Mechanism

The MTH reaction mechanism involves several stages, beginning with the formation of the first C-C bond—a topic of ongoing research. Multiple mechanisms have been proposed, including the methoxymethyl cation mechanism, Koch carbonylation mechanism, and carbene mechanism [34]. Surface methoxy species (SMSs) formed from methanol or dimethyl ether (DME) on Brønsted acid sites are recognized as crucial intermediates in these initial steps [34].

Once initiated, the reaction enters a steady state governed by the hydrocarbon pool mechanism, which is often described by a dual-cycle concept [32] [34]. This concept involves two interwoven catalytic cycles: an alkene cycle, responsible for the formation and consumption of light olefins through repeated methylation and cracking steps, and an aromatic cycle, which involves polyalkylated aromatic hydrocarbons as active intermediates and contributes to both alkene production and the formation of heavier aromatics [34]. The topology of the zeolite catalyst significantly influences the relative propagation of these two cycles, thereby determining the final product distribution.

Ethanol-to-Aromatics (ETA) Mechanism

The ETA conversion mechanism differs fundamentally from MTH due to the presence of a pre-existing C-C bond in ethanol. The reaction pathway begins with rapid dehydration of ethanol to form ethylene, a C₂ species [32]. This ethylene then undergoes oligomerization to form higher molecular weight olefins, which can subsequently undergo cyclization and hydrogen transfer reactions to yield aromatic hydrocarbons [32].

While the MTH process relies heavily on methyl transfer reactions and the hydrocarbon pool mechanism, these pathways occur rather as side reactions in ETA conversion [32]. The immediate availability of C₂ species from ethanol dehydration directs the reaction pathway more directly toward the formation of larger olefins and aromatics, making the oligomerization activity of the catalyst particularly important for ETA performance.

Catalyst Design and Deactivation Behavior

Influence of Crystal Size and Morphology

The crystal size and morphology of zeolite catalysts significantly impact their catalytic performance by influencing diffusion path lengths and accessibility of active sites.

For H-ZSM-5 in MTO conversion, increasing crystal size decreases the catalyst's lifetime but can also alter product distribution by enhancing the propagation of the aromatic-based reaction cycle [32]. The diffusion anisotropy between the straight and sinusoidal channels of H-ZSM-5 becomes a crucial factor, with molecules such as C3-C4 olefins experiencing different diffusional resistances in each channel type [2]. Regulating crystal morphology to control the preferred orientation of pore openings can therefore significantly impact catalytic performance.

In ETA conversion, the effect of crystal size is less pronounced because the instantly available aromatics lead to rapid coking that primarily affects the outer layers of the crystals [32]. This results in only the external surface remaining active, regardless of the overall crystal dimensions.

Deactivation and Coke Formation

Both H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta experience deactivation during alcohol conversion processes, primarily due to coke formation that blocks pores and covers active sites. However, the rate and nature of deactivation differ significantly between the two catalysts.

H-Beta, with its larger pores, suffers from rapid deactivation through coke formation during MTH conversion, which has rendered it unsuitable for industrial applications despite its high initial activity [5]. The large-pore structure accommodates the formation and retention of bulky coke precursors, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which eventually lead to pore blockage.

H-ZSM-5's medium-pore structure imposes spatial constraints on the formation of large polycyclic aromatic species, resulting in generally slower deactivation rates compared to large-pore zeolites like H-Beta [5]. The narrower channels impose shape selectivity that limits the growth and mobility of coke precursors, thereby extending catalyst lifetime.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Catalytic Testing for Benzene Methylation

The comparative kinetics of benzene methylation by methanol over H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta catalysts can be evaluated using a fixed-bed reactor system operated at high feed rates to achieve low conversion, thereby suppressing side reactions and enabling direct measurement of the methylation rate [5].

- Catalyst Preparation: Zeolite catalysts are typically pelletized, crushed, and sieved to obtain specific particle size fractions (e.g., 100-300 μm). Prior to testing, catalysts are activated in situ under dry air flow at elevated temperature (e.g., 500°C) to remove moisture and impurities [5].

- Reaction Conditions:

- Temperature: 350-450°C

- Pressure: Near atmospheric

- Feed composition: Benzene and methanol in an inert carrier gas (e.g., N₂)

- High weight hourly space velocity (WHSV) to maintain low conversion [5]

- Product Analysis: Effluent stream is analyzed using online gas chromatography (GC) with appropriate detectors (FID/TCD) to quantify reactants and products. Key metrics include benzene conversion, methanol conversion, toluene selectivity, and byproduct formation [5].

- Kinetic Parameter Determination: Apparent kinetic coefficients, reaction orders, and Arrhenius parameters (activation energy, pre-exponential factor) are extracted from methylation rates measured at varying temperatures and partial pressures [5].

Catalyst Characterization Techniques

Comprehensive catalyst characterization is essential for correlating catalytic performance with physicochemical properties.

- Acid Site Quantification: Temperature-programmed desorption of ammonia (NH₃-TPD) measures total acid site density and strength distribution. In situ Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) using pyridine or collidine as probe molecules differentiates between Brønsted and Lewis acid sites [32].

- Textural Properties: N₂ physisorption at -196°C determines Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area, micropore volume, and mesoporosity. T-plot or αs-plot methods differentiate between microporous and non-microporous surface areas [32] [30].

- Crystallinity and Phase Purity: X-ray diffraction (XRD) confirms zeolite structure, phase purity, and relative crystallinity. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) reveals crystal morphology, size distribution, and intergrowth features [32] [2].

- Elemental Composition: Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) provides accurate measurement of bulk silicon-to-aluminum (Si/Al) ratio [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for zeolite catalysis studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Zeolite Catalysts | Solid acid catalyst for MTH/ETA reactions | H-ZSM-5 (SiO₂/Al₂O₃: 30-300), H-Beta (SiO₂/Al₂O₃: 25-150) [5] [30] |

| Alcohol Feedstocks | Reactant for hydrocarbon production | Methanol (≥99.9%), Ethanol (anhydrous, ≥99.8%) [32] |

| Probe Molecules | Acid site characterization | Ammonia (NH₃), Pyridine, Collidine [32] |

| Template Agents | Zeolite synthesis & morphology control | Tetrapropylammonium hydroxide (TPAOH), Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) [35] [30] |

| Metal Precursors | Catalyst modification for enhanced functionality | Nickel nitrate hexahydrate [Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O] for hydrogenation function [30] |

H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta zeolites demonstrate distinct catalytic efficacy in alcohol-to-hydrocarbon conversion processes, with their performance dictated by intrinsic structural properties. H-ZSM-5 exhibits superior performance in MTH processes requiring shape selectivity, offering higher methylation rates, enhanced stability against deactivation, and superior selectivity toward light olefins. Its medium-pore architecture provides optimal constraints for the hydrocarbon pool mechanism, particularly in methanol-to-olefins applications.

H-Beta's large-pore system affords superior mass transfer capabilities, making it more effective for reactions involving bulky molecules such as in transalkylation processes and ethanol-to-aromatics conversion where larger intermediates are involved. However, this structural advantage comes with the drawback of accelerated deactivation through coke formation, limiting its industrial applicability in continuous processes.

The choice between these catalysts ultimately depends on process objectives: H-ZSM-5 is preferred for selective production of light olefins from methanol, while H-Beta may be suitable for applications requiring conversion of larger feedstocks or where its superior initial activity can be leveraged in regeneration-equipped systems. Future research directions include the development of hierarchical composites combining the advantages of both materials and the precise control of crystal morphology to optimize diffusion pathways for specific conversion processes.

The Role of Catalyst Morphology and Diffusion Path Lengths in Reactivity

Zeolites, microporous aluminosilicate minerals, are among the most widely used solid acid catalysts in petroleum refining, petrochemical production, and fine chemical synthesis due to their well-defined pore structures, high surface areas, and tunable acidity. The catalytic performance of zeolites is intrinsically linked to their morphological characteristics, including crystal size, shape, and the resulting diffusion path lengths that reactant and product molecules must traverse. Catalyst morphology directly influences mass transfer efficiency, active site accessibility, and reaction selectivity, while diffusion path lengths determine the residence time of molecules within the pore system, thereby affecting both conversion and catalyst deactivation behavior.

This review comprehensively compares two prominent zeolite catalysts—H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta—focusing on how their distinct morphological features and diffusion characteristics govern reactivity across various chemical processes. Understanding these structure-performance relationships enables the rational design of superior catalysts through morphology optimization.

Structural and Morphological Comparison of H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta

Framework Architecture and Active Sites

H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta possess fundamentally different framework structures that dictate their respective morphological characteristics and diffusion properties.

Table 1: Fundamental Structural Properties of H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta Zeolites

| Property | H-ZSM-5 (MFI topology) | H-Beta (BEA topology) |

|---|---|---|

| Channel System | 3D with intersecting straight and sinusoidal channels | 3D with interconnected straight channels |

| Pore Size | 10-membered rings (~5.1-5.6 Å) | 12-membered rings (~6.6 × 6.7 Å) |

| Channel Dimensions | Straight: 5.4 × 5.6 Å (along b-axis)Sinusoidal: 5.1 × 5.4 Å (along a-axis) | 6.6 × 6.7 Å (all directions) |

| Typical Acidity | Strong Brønsted acid sites | Strong Brønsted acid sites |

| Si/Al Range | Wide range possible (e.g., 25-300) | Wide range possible (e.g., 25-300) |

H-ZSM-5 features a three-dimensional pore system with two distinct types of intersecting 10-membered ring channels: straight channels running along the b-axis (5.4 × 5.6 Å) and sinusoidal channels parallel to the a-axis (5.1 × 5.4 Å) [2]. This creates an anisotropic diffusion environment where molecule transport differs significantly depending on channel orientation and crystal morphology.

H-Beta possesses a fully three-dimensional system of 12-membered ring channels (approximately 6.6 × 6.7 Å) with interconnected straight channels in all directions, creating a more isotropic diffusion environment compared to H-ZSM-5 [36]. The larger pore size of H-Beta accommodates bulkier molecules but with reduced shape selectivity compared to H-ZSM-5.

Morphology Control and Hierarchical Structures

H-ZSM-5 Morphology Control: Synthesis conditions can produce H-ZSM-5 crystals with diverse morphologies. Sheet-like ZSM-5 with controlled c-axis lengths (548-1530 nm) but similar a-axis (~250 nm) and b-axis (~100 nm) dimensions demonstrated that longer c-axis correlates with higher [010] facet exposure (up to 68.9%) and increased straight channel accessibility [2]. Nanosheet ZSM-5 with extremely short b-axis thickness (~2 nm) significantly reduces diffusion path lengths along the sinusoidal channels [37]. Particle size variations from 0.13 μm to 13 μm dramatically affect reactivity, with smaller particles exhibiting enhanced activity due to shorter diffusion paths [37].

H-Beta Morphology Engineering: Beta zeolite can be synthesized with hierarchical porosity through organofunctionalization of zeolitic seeds, creating materials with enhanced textural properties [36]. This approach generates additional porosity in the supermicropore-mesopore region, improving diffusion for bulky molecules. Alkali treatments (e.g., NaOH) effectively shorten diffusion path lengths in Beta zeolites by creating intracrystalline mesoporosity while maintaining crystalline structure [38].

Diffusion Characteristics and Mass Transfer Limitations

Anisotropic Diffusion in H-ZSM-5

The intersecting channel system of H-ZSM-5 exhibits pronounced diffusion anisotropy, particularly for hydrocarbon molecules approaching the pore dimensions. Time-resolved in-situ FT-IR spectroscopy and molecular dynamics simulations reveal different intracrystalline diffusive propensities in straight versus sinusoidal channels [2]. For C4 olefins, this anisotropy significantly impacts catalytic cracking performance, with diffusion constraints more pronounced in the sinusoidal channels.

The morphology descriptor based on diffusion anisotropy links crystal shape to catalytic function: crystals with longer c-axes and higher [010] facet exposure provide greater straight channel accessibility, reducing diffusion limitations for linear olefins [2]. This explains the superior performance of Z-cL (long c-axis) samples in C4 olefin catalytic cracking, maintaining 40% conversion and 18% C2-3 yield after 50 hours compared to rapid deactivation of shorter c-axis counterparts.

Mass Transfer in H-Beta Zeolite

H-Beta's larger pore dimensions (12-membered rings) typically experience reduced mass transfer limitations for most hydrocarbon molecules compared to H-ZSM-5. However, significant diffusion constraints still occur in reactions involving bulky intermediates. In the Diels-Alder conversion of 2,5-dimethylfuran and acrylic acid to para-xylene, H-Beta exhibits substantial mass transfer limitations, which can be mitigated through alkali treatments that create mesopores and shorten diffusion path lengths [38].

For H-Beta catalyzed reactions, the Al distribution within the framework influences both acidity and structural stability. Theoretical studies indicate preferential Al siting at T7 and T9 positions, with these sites also being more prone to dealumination, potentially creating secondary porosity that modifies diffusion characteristics [39].

Catalytic Performance in Model Reactions

Hydrocarbon Conversion and Cracking

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Hydrocarbon Conversion Reactions

| Reaction | H-ZSM-5 Performance | H-Beta Performance | Key Morphology Influence |

|---|---|---|---|

| C4 Olefin Cracking | High initial activity, stability improves with longer c-axis morphology [2] | Not specifically reported | Diffusion anisotropy; straight channel accessibility |

| n-Heptane Cracking | Higher conversion with smaller particle sizes (0.13 μm > 13 μm) [37] | Not directly comparable | Crystal size; diffusion path length |

| LDPE Pyrolysis to Aromatics | Product range: C6-C13; limited by pore size [11] | Product range: C6-C20; accommodates larger molecules [11] | Pore diameter; shape selectivity |

| Ethylene Conversion to Propylene | Rate increases with decreasing particle size; nanosheet shows low activity due to short residence time [37] | Not specifically reported | Crystal size; confinement effects |

In catalytic cracking reactions, H-ZSM-5 with shorter diffusion paths (smaller particles or optimized morphology) demonstrates superior activity and stability. For example, in ethylene conversion, the reaction rate increases significantly with decreasing particle size (0.13 μm > 13 μm), though nanosheet ZSM-5 with 1.8 nm thickness shows unexpectedly low activity attributed to insufficient residence time within the ultrathin crystals [37].

In polyolefin pyrolysis, H-ZSM-5 produces lighter aromatics (C6-C13) due to pore size constraints, while H-Beta generates a broader carbon number distribution (C6-C20) compatible with its larger pores [11]. This highlights the critical role of pore architecture in product distribution.

Shape-Selective and Bifunctional Reactions

Bio-based Aromatization: In Diels-Alder conversion of 2,5-dimethylfuran and acrylic acid to para-xylene, H-Beta generally outperforms H-ZSM-5 due to better accommodation of reaction intermediates [38]. Within Beta zeolites, hierarchical porosity significantly enhances performance by reducing mass transfer limitations.

Aromatic Alcohol Conversion: In the tandem dehydration-isomerization of 3-phenylpropanol to 1-propenylbenzene, H-ZSM-5 exhibits superior shape selectivity (95.6% selectivity) compared to H-Beta (79.5%) and USY (68.1%) [40]. This demonstrates H-ZSM-5's advantage in sterically constrained reactions where transition state selectivity dominates.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Synthesis and Morphology Control Protocols

H-ZSM-5 with Controlled Morphology:

- Sheet-like H-ZSM-5: Synthesis from precursor solutions with structure-directing agents under hydrothermal conditions (typically 150-180°C for 24-72 hours) [2]. C-axis length control achieved through crystallization time, temperature, and template concentration.

- Nanosheet H-ZSM-5: Using diquaternary ammonium-type surfactants as structure-directing agents to create ultra-thin (2 nm) crystalline sheets [37].

- Small-particle H-ZSM-5: Controlled nucleation and growth conditions using tetrapropylammonium hydroxide (TPAOH) as template with limited crystal growth time [37].

Hierarchical H-Beta:

- Organofunctionalized Seeds Method: Precrystallization of Beta gel followed by seed silanization with organosilanes before final crystallization [36]. Creates hierarchical porosity with enhanced surface area and pore volume.

- Alkali Treatment: Controlled desilication of conventional H-Beta using NaOH solutions (0.1-1.0 M) at 40°C for 2 hours [38]. Creates intracrystalline mesoporosity while preserving crystalline structure.

Characterization Techniques for Morphology and Diffusion Analysis

- Time-resolved in-situ FT-IR Spectroscopy: Tracks molecular diffusion through zeolite crystals by monitoring characteristic IR bands over time [2].

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Models molecular trajectories through zeolite pore systems to predict diffusion coefficients and anisotropy [2].

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Determines crystal structure, phase purity, and relative crystallinity after modifications [38].

- Adsorption Measurements (N₂, Ar): Quantifies surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution [2] [40].

- Acidity Characterization (NH₃-TPD, Pyridine FT-IR): Measures concentration and strength of Brønsted and Lewis acid sites [11] [38].

Visualization of Morphology-Diffusion-Reactivity Relationships

Diagram 1: Morphology-Diffusion-Reactivity Relationships in H-ZSM-5 and H-Beta Zeolites

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Methods

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Solutions

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Catalyst Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Tetrapropylammonium hydroxide (TPAOH) | Structure-directing agent for ZSM-5 synthesis | Creating specific MFI morphology [41] [37] |