Machine Learning for Catalytic Activity Prediction: A Comprehensive Guide for Accelerated Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in predicting catalytic activity, a critical task for researchers in drug development and materials science.

Machine Learning for Catalytic Activity Prediction: A Comprehensive Guide for Accelerated Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in predicting catalytic activity, a critical task for researchers in drug development and materials science. It explores the foundational shift from empirical, trial-and-error methods to data-driven discovery paradigms, detailing key ML algorithms and their specific applications in optimizing reaction conditions, elucidating mechanisms, and designing novel catalysts. The content further addresses central challenges such as data scarcity and model interpretability, offering troubleshooting strategies and validation frameworks. By synthesizing methodological insights with comparative analyses, this guide equips scientists with the knowledge to leverage ML for accelerating catalyst screening, enhancing predictive accuracy, and informing rational design in biomedical and clinical research.

From Trial-and-Error to Data-Driven Discovery: The New Paradigm in Catalysis

The integration of machine learning (ML) into catalysis research represents a transformative approach to accelerating catalyst discovery and optimization. ML techniques efficiently navigate vast, multidimensional chemical spaces, uncovering complex patterns and relationships that traditional experimental and computational methods can miss due to their time-consuming and resource-intensive nature [1] [2]. At the heart of this data-driven revolution are two fundamental learning paradigms: supervised learning, which predicts catalytic properties from labeled data, and unsupervised learning, which discovers hidden structures and patterns within unlabeled data [3] [4]. The choice between these paradigms is primarily dictated by the nature of the available data and the specific research objective, whether it is predicting a catalyst's performance or uncovering new classifications of catalytic materials [1].

This article provides a structured guide to applying these core ML concepts within catalytic activity prediction research. It details specific protocols, presents comparative data, and outlines essential computational tools, offering a practical framework for researchers to implement these techniques in their work.

Core Concepts and Comparative Analysis

Supervised vs. Unsupervised Learning: Definitions and Catalytic Applications

Supervised learning operates like a student learning with a teacher. The algorithm is trained on a labeled dataset where each input example (e.g., a catalyst's descriptor set) is paired with a known output value (e.g., adsorption energy or reaction yield). The model learns the mapping function from the inputs to the outputs, which it can then use to make predictions on new, unseen catalyst data [3] [4]. Its applications in catalysis are predominantly predictive, including forecasting catalyst efficiency, reaction yields, and selectivity [5] [1].

Unsupervised learning, in contrast, involves a machine exploring data without a teacher-provided answer key. The algorithm is given unlabeled data and must independently identify the inherent structure, patterns, or groupings within it [3] [6]. This approach is primarily used for knowledge discovery in catalysis, such as identifying novel catalyst families through clustering or reducing the dimensionality of complex feature spaces for visualization [7] [1].

Structured Comparison of ML Techniques

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of these two learning approaches in a catalytic research context.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Supervised vs. Unsupervised Learning

| Parameter | Supervised Learning | Unsupervised Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Input Data | Labeled data (input-output pairs) [3] [4] | Unlabeled data (inputs only) [3] [6] |

| Primary Goal | Prediction of known catalytic properties [1] | Discovery of hidden patterns or groups [1] |

| Common Tasks | Regression (e.g., yield prediction), Classification (e.g., high/low activity) [3] | Clustering, Dimensionality Reduction [3] [1] |

| Catalysis Examples | Predicting adsorption energy of single-atom catalysts [5]; Forecasting reaction yield [8] | Grouping ligands by similarity [1]; Identifying catalyst trends via PCA [7] |

| Feedback Mechanism | Direct feedback via prediction error against known labels [4] | No feedback mechanism; success is based on utility of findings [3] |

| Advantages | High predictive accuracy; interpretable results [1] | No need for labeled data; reveals previously unknown insights [3] |

| Disadvantages | Requires costly, well-labeled datasets; risk of overfitting [3] | Results can be harder to interpret; lower predictive power [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Catalytic Activity Prediction

This section outlines detailed methodologies for implementing supervised and unsupervised learning in catalytic research, using published studies as a guide.

Protocol 1: Supervised Learning for Adsorption Energy Prediction

This protocol is adapted from studies predicting key properties of single-atom catalysts (SACs), such as adsorption energy for CO~2~ reduction [5].

Objective: To train a supervised learning model capable of predicting the adsorption energy of molecules on single-atom catalyst surfaces.

Materials & Data Sources:

- Dataset: A curated set of SAC structures with corresponding adsorption energies, often derived from Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations [5].

- Descriptors: Features (inputs) include elemental properties of the metal center, local coordination environment, and electronic structure descriptors [7].

- Target Variable: The adsorption energy (output) from DFT [5].

Procedure:

- Data Collection & Curation: Compile a dataset from computational databases like the Materials Project (MP) or Catalysis-Hub.org. The dataset should include final energy per atom, band gap, and other relevant DFT-calculated properties [5].

- Feature Engineering: Calculate and select meaningful catalyst descriptors. These can be geometric, electronic, or compositional features that are hypothesized to influence adsorption strength [7].

- Model Training & Selection:

- Model Evaluation: Assess the final model's performance on the held-out test set using metrics like Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) to quantify prediction accuracy against DFT-calculated values [5] [8].

Protocol 2: Unsupervised Learning for Catalyst Classification

This protocol describes using clustering to identify groups of catalysts with similar characteristics without prior knowledge of performance labels [1].

Objective: To identify inherent groupings within a library of catalysts or ligands based on their molecular descriptors.

Materials & Data Sources:

- Dataset: A collection of unlabeled catalyst or ligand structures (e.g., a set of organometallic complexes) [1].

- Descriptors: Molecular fingerprints or features capturing steric and electronic properties (e.g., feature vectors from RDKit, electronic parameters, steric maps).

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Compile structural data for all catalysts in the study. Generate molecular descriptors or fingerprints for each catalyst to create a feature matrix [1].

- Dimensionality Reduction (Optional): Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the feature space dimensionality. This simplifies clustering and allows for visualization of the catalyst landscape in 2D or 3D plots [7] [1].

- Clustering Algorithm Application:

- Apply a clustering algorithm such as K-means to the descriptor data.

- Determine the optimal number of clusters (K) using methods like the elbow method or silhouette analysis [6].

- Cluster Interpretation & Validation:

- Analyze the formed clusters to identify common structural or electronic traits within each group.

- Validate the chemical relevance of the clusters by comparing them to known catalyst classifications or by examining their performance in catalytic reactions post-hoc [1].

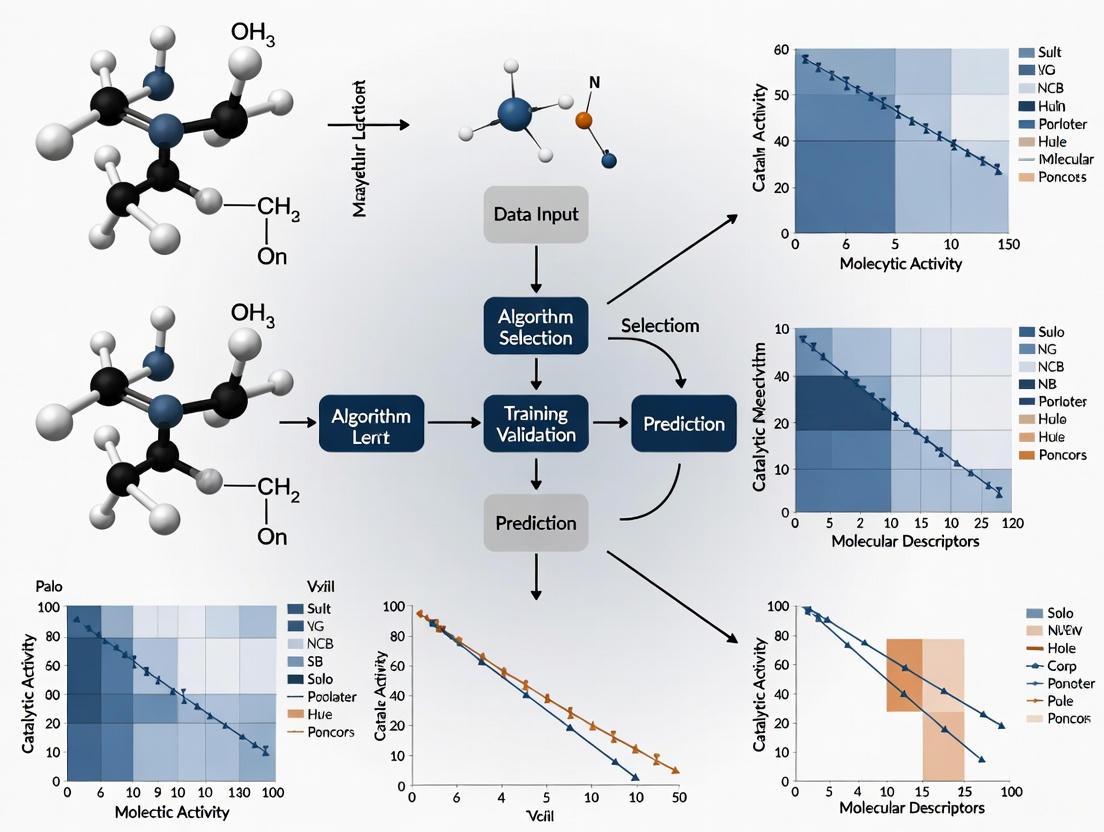

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a generalized ML workflow for catalytic activity prediction, integrating both supervised and unsupervised elements.

Successful implementation of ML in catalysis relies on a suite of software tools and data resources.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for ML in Catalysis

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn [10] | Software Library | Provides robust implementations of classic ML algorithms (RF, SVM, PCA). | Building and evaluating a Random Forest model for yield prediction [9]. |

| TensorFlow/PyTorch [10] | Software Library | Frameworks for building and training deep neural networks. | Developing a complex model for catalyst property prediction [8]. |

| pymatgen [7] | Software Library | Python library for materials analysis; helps generate material descriptors. | Processing crystal structures of catalysts to compute input features [7]. |

| Materials Project (MP) [5] [7] | Database | Repository of computed material properties for inorganic crystals. | Sourcing DFT-calculated formation energies and band structures for training [5]. |

| Catalysis-Hub.org [7] | Database | Specialized database for reaction and activation energies on surfaces. | Obtaining adsorption energies for catalytic reactions to use as training labels [7]. |

| Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) [7] | Software Library | Set of tools for setting up, controlling, and analyzing atomistic simulations. | Automating high-throughput DFT calculations to build a custom dataset [7]. |

| CatDRX Framework [8] | Generative Model | A variational autoencoder for generative catalyst design conditioned on reactions. | Generating novel catalyst candidates for a specific reaction type [8]. |

Supervised and unsupervised machine learning offer powerful, complementary pathways for advancing catalytic science. Supervised learning provides a direct route to predictive modeling of catalyst performance, while unsupervised learning excels at exploratory data analysis and uncovering intrinsic patterns within complex catalyst libraries. The choice of approach is not rigid; a research workflow often benefits from combining both, for instance, using unsupervised clustering to segment data before building specialized supervised models for each cluster. As data availability continues to grow and algorithms become more sophisticated, the integration of these ML paradigms will undoubtedly play a central role in the rational and accelerated design of next-generation catalysts.

In the pursuit of sustainable energy and efficient chemical production, the rational design of high-performance catalysts is paramount. [11] Central to this endeavor are catalytic descriptors—quantitative or qualitative measures that capture the key properties of a system, enabling researchers to understand the fundamental relationship between a material's atomic structure and its catalytic function. [12] The advent of machine learning (ML) has revolutionized this field, providing powerful data-driven tools to navigate the vast complexity of catalytic systems and uncover intricate structure-activity relationships. [1] This Application Note details the core categories of catalytic descriptors and provides structured protocols for their application within ML frameworks, focusing on bridging atomic-scale structural information to macroscopic catalytic activity and selectivity.

Categories of Key Catalytic Descriptors

Catalytic descriptors can be broadly classified based on the fundamental properties they represent. The following table summarizes the primary types, their basis, and their applications.

Table 1: Key Categories of Catalytic Descriptors

| Descriptor Category | Physical/Chemical Basis | Example Descriptors | Primary Application in Catalyst Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Descriptors [12] | Thermodynamic states of reaction intermediates | Binding Energy, Adsorption Free Energy (e.g., ΔGH, ΔGO, ΔGOH) | Predicting catalytic activity trends via volcano plots; assessing stability of intermediates. |

| Electronic Descriptors [12] | Electronic structure of the catalyst material | d-band center, Density of States (DOS), HOMO/LUMO energy | Explaining and predicting adsorption strength and surface reactivity. |

| Geometric/Structural Descriptors [11] | Local atomic environment and coordination | Coordination Number (CN), Atomic Radius, Bond Lengths | Differentiating adsorption site motifs and capturing strain effects. |

| Data-Driven/Composite Descriptors [13] [14] | Multidimensional feature space from data or theory | ML-derived feature importance (e.g., ODI_HOMO_1_Neg_Average), "One-hot" encoded additives |

Capturing complex, non-linear structure-property relationships not evident from single descriptors. |

Quantitative Performance of ML Models Using Advanced Descriptors

The predictive accuracy of machine learning models is highly dependent on the richness and uniqueness of the atomic structure representations (descriptors) used. The following table compiles performance metrics from recent studies employing advanced descriptive methodologies.

Table 2: Performance of ML Models with Enhanced Structural Representations

| ML Model | Key Descriptor / Representation Strategy | Catalytic System | Performance (Mean Absolute Error - MAE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equivariant Graph Neural Network (EquivGNN) [11] | Equivariant message-passing enhanced representation resolving chemical-motif similarity. | Diverse descriptors at metallic interfaces (complex adsorbates, high-entropy alloys, nanoparticles). | < 0.09 eV across all systems |

| Graph Attention Network (GAT-wCN) [11] | Connectivity-based graph with atomic numbers as nodes and Coordination Numbers (CN) as enhanced features. | Atomic-carbon monodentate adsorption on ordered surfaces (Cads Dataset). | 0.128 eV (Formation energy of M-C bond) |

| GAT without CNs (GAT-w/oCN) [11] | Basic connectivity-based graph structure without coordination numbers. | Atomic-carbon monodentate adsorption on ordered surfaces (Cads Dataset). | 0.162 eV (Formation energy of M-C bond) |

| Random Forest with CNs [11] | Site representation supplemented with coordination numbers. | Atomic-carbon monodentate adsorption on ordered surfaces (Cads Dataset). | 0.186 eV (Formation energy of M-C bond) |

| XGBoost [13] | Composite descriptors from DFT and molecular features (e.g., ODI_HOMO_1_Neg_Average, ALIEmax GATS8d). |

Ti-phenoxy-imine catalysts for ethylene polymerization. | R² (test set) = 0.859 |

Experimental Protocol: Predicting Binding Energies with Graph Neural Networks

This protocol details the methodology for employing an Equivariant Graph Neural Network (EquivGNN) to predict binding energies of adsorbates on catalyst surfaces, a critical energy descriptor. [11]

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and machine learning workflow for descriptor prediction.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: System Definition and Dataset Curation

- Action: Define the scope of the catalytic system (e.g., monodentate adsorbates on pure metals, bidentate adsorbates on alloys, or nanoparticles). [11]

- Protocol: Assemble a dataset of atomic structures. Structures can be obtained from relaxed or unrelaxed Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations or crystallographic databases. Each structure must be paired with its target property (e.g., binding energy from DFT).

Step 2: Graph Representation of Atomic Structures

- Action: Convert each atomic structure into a graph. [11]

- Protocol:

- Nodes: Represent individual atoms.

- Edges: Connect pairs of atoms that are chemically bonded or within a specified cutoff radius.

- Node Features: Encode atom-specific information (e.g., atomic number, atomic weight). Enhanced models can include Coordination Number (CN) as a critical node feature to significantly improve accuracy. [11]

- Edge Features: Can include spatial information such as interatomic distance and vector direction, which is crucial for equivariant models.

Step 3: Model Architecture and Training

- Action: Construct and train the Equivariant Graph Neural Network.

- Protocol:

- Architecture: Utilize an equivariant message-passing framework. In this process, node features are updated by aggregating ("passing") information from their neighboring nodes. [11]

- Equivariance: The model is designed to be equivariant to rotation and translation, meaning its predictions are consistent regardless of the system's orientation in space. This is essential for capturing true physical relationships.

- Readout/Global Pooling: After several message-passing layers, the updated node features from the entire graph are aggregated into a single, graph-level representation. [11]

- Output Layer: This graph-level representation is passed through a final neural network layer to predict a scalar value, such as the binding energy.

Step 4: Validation and Prediction

- Action: Evaluate model performance and deploy for predictions.

- Protocol:

- Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold CV) to assess model generalizability. Compare predicted binding energies against DFT-calculated values using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE). [11]

- Prediction: Use the trained model to predict binding energies for new, unseen atomic structures, enabling rapid screening of candidate materials.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational and Experimental Tools for Descriptor-Driven Catalyst Research

| Item / Solution | Function / Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) [12] [13] | Computational method to calculate electronic structure properties, such as adsorption energies and d-band centers. | Generating training data and target values for energy and electronic descriptors. |

| Equivariant Graph Neural Network (EquivGNN) [11] | ML model architecture that respects physical symmetries (rotation/translation invariance) in 3D space. | Accurately predicting descriptors for complex systems with diverse adsorption motifs. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) [14] | Automated platforms for rapidly testing thousands of catalyst recipes or reaction conditions. | Generating large, consistent experimental datasets for building robust data-driven ML models. |

| One-Hot Vectors / Molecular Fragment Featurization (MFF) [14] | Method to convert categorical variables (e.g., presence of a functional group) into a numerical format ML models can understand. | Encoding catalyst recipe information (e.g., additives) as input descriptors for predictive models. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) Analysis [13] | A technique for interpreting the output of ML models by quantifying the contribution of each input descriptor to the final prediction. | Identifying the most critical descriptors governing catalytic activity or selectivity from a complex model. |

Advanced Application: Multi-Round Learning for Catalyst Optimization

For complex experimental systems, such as tuning catalyst selectivity with additives, a multi-round ML strategy is highly effective. The following protocol is adapted from a study on CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR) catalysts. [14]

This iterative learning process efficiently narrows down the optimal catalyst recipe from a vast possibility space.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Round 1: Initial Screening with Macro-Descriptors

- Objective: Identify the most impactful metal additives and broad functional groups.

- Protocol:

- Descriptor Definition: Use one-hot encoding to create descriptors indicating the presence or absence of specific metals (e.g., Sn, Cu) and functional groups (e.g., aliphatic -OH, -NH₂) in a catalyst recipe. [14]

- Model Training: Train classification (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost) and regression models to predict product selectivity (e.g., Faradaic Efficiency for CO, C₂⁺ products) from these descriptors. [14]

- Output: A ranked list of the most important metal and organic group features.

Round 2: Refinement with Local Structure Descriptors

- Objective: Understand the influence of specific molecular fragments.

- Protocol:

- Descriptor Definition: Transform the structural information of organic additives using Molecular Fragment Featurization (MFF) to create a more detailed feature matrix. [14]

- Model Training: Retrain ML models using these new, more granular descriptors.

- Output: Insights into how specific local structures (e.g., nitrogen heteroaromatic rings vs. aliphatic amines) influence selectivity.

Round 3: Synergistic Effect Analysis

- Objective: Discover non-linear, synergistic interactions between descriptor combinations.

- Protocol:

- Descriptor Definition: Use algorithms like Random Intersection Trees to find frequent and impactful combinations of the features identified in Rounds 1 and 2. [14]

- Model Application: Identify pairs or triplets of features that, when present together, have a positive or negative synergistic effect on the target property (e.g., aliphatic -OH combined with an aliphatic amine enhances C₂⁺ selectivity). [14]

- Output: A set of design rules for formulating high-performing catalyst recipes.

Final Step: Design and Experimental Validation

- Action: Propose and test new catalysts.

- Protocol: Design new catalyst compositions based on the derived ML rules. These candidates are then synthesized and tested experimentally to validate the model's predictions and confirm the discovery of improved catalysts. [14]

The field of catalysis research is undergoing a profound transformation, shifting from traditional trial-and-error experimentation and theoretical simulations toward a new paradigm rooted in data-driven scientific discovery. This transition is largely fueled by the integration of high-throughput experimentation (HTE) and machine learning (ML), which together are accelerating the design and optimization of catalysts for applications ranging from renewable energy to pharmaceutical development. However, the effectiveness of this approach is critically dependent on overcoming significant data challenges, including the generation of high-quality, standardized datasets and the implementation of robust database curation practices that ensure data findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability (FAIR). The historical development of catalysis can be delineated into three stages: the initial intuition-driven phase, the theory-driven phase represented by density functional theory (DFT), and the current emerging stage characterized by the integration of data-driven models with physical principles [15]. In this third stage, ML has evolved from being merely a predictive tool to becoming a "theoretical engine" that contributes to mechanistic discovery and the derivation of general catalytic laws.

The performance of ML models in catalysis is highly dependent on data quality and volume [15]. Although the rise of high-throughput experimental methods and open-access databases has significantly promoted data accumulation in catalysis, data acquisition and standardization remain major challenges for ML applications in this domain [15]. High-throughput experimentation (HTE) is a method of scientific inquiry that facilitates the evaluation of miniaturized reactions in parallel [16]. This approach advances the assessment of a range of experiments, allowing the exploration of multiple factors simultaneously in contrast to the traditional one variable at a time (OVAT) method. When applied to organic chemistry, HTE enables accelerated data generation, providing a wealth of information that can be leveraged to access target molecules, optimize reactions, and inform reaction discovery while enhancing cost and material efficiency. Additionally, HTE has proven effective in collecting robust and comprehensive data for machine learning (ML) algorithms that are more accurate and reliable [16].

Quantitative Landscape of Catalysis Data and ML Performance

The effectiveness of ML-driven catalysis research hinges on the quality and volume of available data, as well as the performance of the algorithms processing this information. The field has seen significant advancements in data generation and model accuracy, with specific benchmarks established for various catalyst types and predictive tasks.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of ML Models for Catalytic Activity Prediction

| Catalyst System | ML Model | Key Features | Performance (R²/MAE) | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-type HECs | Extremely Randomized Trees (ETR) | 10 minimal features including φ = Nd0²/ψ0 | R² = 0.922 | Catalysis-hub (10,855 structures) [17] |

| Metallic Interfaces | Equivariant GNN (equivGNN) | Enhanced atomic structure representations | MAE < 0.09 eV for binding energies | Custom datasets [11] |

| Binary Alloys | Random Forest Regression (RFR) | Coordination numbers as local environment feature | MAE: 0.186 eV (vs. 0.346 eV without CN) | Cads Dataset [11] |

| Transition Metal Single-Atoms | CatBoost Regression | 20 features | R² = 0.88, RMSE = 0.18 eV | Literature data [17] |

| Double-Atom Catalysts | Random Forest Regression | 13 features | R² = 0.871, MSE = 0.150 | Computational data [17] |

Table 2: Catalysis Database Characteristics and Applications

| Database Name | Data Content | Size | Primary Use Cases | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalysis-hub | Hydrogen adsorption free energies and corresponding adsorption structures | 11,068 HER free energies (10,855 after filtering) | Training ML models for HER catalyst prediction | Open-access, peer-reviewed [17] |

| Material Project | Material structures and properties | N/A | Discovery of new catalyst candidates | Open database [17] |

| High-Throughput Experimentation Databases | Reaction conditions, yields, and characterization data | 1536 reactions simultaneously (ultra-HTE) | Reaction optimization and discovery | Often institutional [16] |

The data in Catalysis-hub, which includes various types of hydrogen evolution catalysts (HECs) such as pure metals, transition metal intermetallic compounds, light metal intermetallic compounds, non-metallic compounds, and perovskites, exemplifies the diverse data sources available for ML training [17]. All data in this database are derived from DFT calculations and are sourced from published literature, peer-reviewed, and validated to ensure data accuracy. The distribution of free energies of the HECs in this dataset ranges from -12.4 to 22.1 eV, with 95.5% of the data falling within the range of [-2, 2] eV, which is particularly relevant for catalytic activity prediction [17].

High-Throughput Experimentation: Protocols and Workflows

High-throughput experimentation represents a foundational methodology for generating the extensive datasets required for robust ML model training in catalysis. Modern HTE originates from well-established high-throughput screening (HTS) protocols from the 1950s that were used predominately to screen for biological activity [16]. The adoption of HTE for chemical synthesis was limited until successful examples of its application were demonstrated between the mid-1990s and early 2000s, when automation was repurposed for chemical synthesis and reaction development with advancement in commercial equipment that are compatible with a range of different types of chemistry and in situ reaction monitoring [16].

HTE Experimental Protocol for Catalyst Screening

Objective: To rapidly screen multiple catalyst candidates and reaction conditions in parallel for catalytic activity assessment.

Materials and Equipment:

- Automated liquid handling systems

- Microtiter plates (96-well, 384-well, or 1536-well formats)

- Inert atmosphere chambers (for air-sensitive reactions)

- High-throughput analytical platforms (e.g., HPLC, GC-MS, LC-MS)

- Automated reaction monitoring systems

Procedure:

- Experimental Design: Strategically select variables to test (catalysts, solvents, ligands, substrates, temperatures) using statistical design of experiments (DoE) principles to maximize information gain while minimizing the number of experiments.

- Plate Preparation: Arrange reaction vessels in microtiter plates, considering spatial bias effects where center and edge wells may experience different conditions [16].

- Reagent Dispensing: Use automated liquid handlers to dispense reagents in microliter to nanoliter volumes with high precision. Account for solvent properties (surface tension, viscosity) that may affect dispensing accuracy [16].

- Reaction Execution: Conduct reactions under controlled conditions (temperature, atmosphere, mixing). For photoredox chemistry, ensure consistent light irradiation across all wells [16].

- Reaction Monitoring: Employ in-situ analytical techniques or quench reactions at predetermined timepoints.

- Product Analysis: Utilize high-throughput analytical methods to quantify reaction outcomes (yield, selectivity, conversion).

- Data Recording: Record all reaction parameters and outcomes in standardized formats with appropriate metadata.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Include control reactions and replicates to assess reproducibility

- Implement randomization to avoid systematic errors

- Validate miniaturized reaction outcomes against traditional scale reactions

- Account for evaporation effects in microscale reactions [16]

HTE-ML Integration Workflow

Today, HTE strategies for chemical synthesis can be broadly utilized toward different objectives depending on the research goals, including building libraries of diverse target compounds, reaction optimization where multiple variables are simultaneously varied to identify an optimal condition, and reaction discovery to identify unique transformations [16]. The introduction of ultra-HTE, which allows for testing 1536 reactions simultaneously, has significantly accelerated data generation and broadened the ability to examine reaction chemical space [16].

Database Curation Frameworks and Data Stewardship

Robust database curation is essential for transforming raw experimental and computational data into valuable, reusable resources for the catalysis community. Effective data stewardship ensures that datasets adhere to FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable), enabling their effective use in ML applications.

Data Curation Protocol for Catalysis Databases

Objective: To implement comprehensive data curation practices that enhance data quality, interoperability, and reusability for ML-driven catalysis research.

Procedure:

- Data Collection and Ingestion:

- Acquire data from diverse sources (experimental measurements, computational simulations, literature extracts)

- Implement automated data validation checks during ingestion

- Record provenance information including experimental conditions, computational parameters, and measurement techniques

Data Standardization:

- Apply standardized nomenclature for chemical structures (IUPAC names, SMILES, InChI identifiers)

- Use consistent units and measurement standards across datasets

- Implement metadata standards following frameworks such as MIAME (Minimum Information About a Microarray Experiment) and MIBI (Minimum Information in Biological Imaging) [18]

Quality Control and Validation:

- Perform outlier detection using statistical methods

- Validate computational data through convergence tests and method benchmarks

- Cross-validate experimental data through replicates and control experiments

Feature Engineering and Descriptor Calculation:

- Compute catalytic descriptors (e.g., d-band center, coordination numbers, adsorption energies)

- Generate structural features using atomic simulation environments [17]

- Implement feature selection algorithms to identify the most relevant descriptors

Data Storage and Management:

- Utilize structured databases with appropriate schema design

- Implement version control for dataset updates

- Establish data backup and preservation protocols

Data Access and Sharing:

- Implement access control mechanisms based on user roles

- Provide APIs for programmatic data access

- Apply FAIR data principles to maximize reusability [18]

Implementation Considerations:

- Develop Data Management Plans (DMPs) at project inception

- Utilize attribute-based access control for sensitive data

- Implement blockchain technology for enhanced data integrity and traceability in certain applications [19]

The integration of diverse data types—ranging from sequencing and clinical data to proteomic and imaging data—highlighted the complexity and expansive scope of AI applications in these fields [18]. The current challenges identified in AI-based data stewardship and curation practices include lack of infrastructure and cost optimization, ethical and privacy considerations, access control and sharing mechanisms, large scale data handling and analysis and transparent data-sharing policies and practice [18].

Data Curation Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The successful implementation of HTE and database curation in catalysis research relies on a suite of specialized tools, reagents, and computational resources. This toolkit enables researchers to generate high-quality data efficiently and process it effectively for ML applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Catalysis Data Science

| Category | Item | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| HTE Hardware | Automated Liquid Handling Systems | Precision dispensing of µL-nL volumes | High-throughput reaction setup [16] |

| Microtiter Plates | 96-well, 384-well, 1536-well formats | Parallel reaction execution [16] | |

| Inert Atmosphere Chambers | Control of oxygen and moisture levels | Air-sensitive catalytic reactions [16] | |

| Analytical Tools | High-Throughput LC-MS/GC-MS | Rapid analysis of reaction mixtures | Reaction outcome determination [16] |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | High-sensitivity detection and quantification | Reaction monitoring [16] | |

| Computational Resources | VASP (Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package) | DFT calculations for material properties | High-throughput computational screening [20] |

| Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) | Python module for atomistic simulations | Automated feature extraction [17] | |

| VASPKIT | Pre- and post-processing of VASP calculations | Automation of DFT workflows [20] | |

| Data Management | FAIR Data Infrastructure | Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable data | Database curation and sharing [18] |

| Data Management Plans (DMPs) | Documentation of data handling procedures | Project data governance [18] | |

| ML Algorithms | Random Forest Regression | Ensemble learning for property prediction | Catalytic activity prediction [17] [11] |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Learning from graph-structured data | Structure-property relationships [11] | |

| Extremely Randomized Trees (ETR) | High-performance regression with minimal features | Multi-type catalyst prediction [17] |

Case Study: ML-Driven Hydrogen Evolution Reaction Catalyst Discovery

The integration of HTE and curated databases with ML is powerfully illustrated by recent advances in hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) catalyst discovery. HER is an important strategy to cope with the global energy shortage and environmental degradation, and given the large cost involved in HER, it is crucial to screen and develop stable and efficient catalysts [20]. The development of an efficient ML model to predict HER activity across diverse catalysts demonstrates the potential of this integrated approach.

In one notable study, researchers obtained atomic structure features and hydrogen adsorption free energy (ΔGH) data for 10,855 HECs from Catalysis-hub for training and prediction [17]. The dataset included various types of HECs, such as pure metals, transition metal intermetallic compounds, light metal intermetallic compounds, non-metallic compounds, and perovskite. Using only 23 features based on atomic structure and electronic information of the catalyst active sites, without the need for additional DFT calculations, they established six ML models, with the Extremely Randomized Trees (ETR) model achieving superior performance with an R² score of 0.921 for predicting ΔGH [17].

Through feature importance analysis and feature engineering, the researchers reselected and identified more relevant features, reducing the number of features from 23 to 10 and improving the R² score to 0.922 [17]. This feature minimization approach introduced a key energy-related feature φ = Nd0²/ψ0, which correlates with HER free energy [17]. The time consumed by the ML model for predictions is one 200,000th of that required by traditional density functional theory (DFT) methods [17]. This case study exemplifies how the combination of curated data, appropriate feature engineering, and optimized ML algorithms can dramatically accelerate catalyst discovery while reducing computational costs.

The integration of high-throughput experimentation, rigorous database curation, and machine learning represents a transformative approach to addressing the data challenges in catalysis research. By implementing standardized protocols for data generation, curation, and management, researchers can build high-quality datasets that enable the development of accurate predictive models for catalytic activity. As these methodologies continue to evolve and become more accessible, they hold the potential to significantly accelerate the discovery and optimization of catalysts for sustainable energy applications, pharmaceutical development, and industrial processes. The future of catalysis research lies in the continuous refinement of these data-driven approaches, fostering collaboration between experimentalists, theoreticians, and data scientists to overcome existing limitations and unlock new opportunities in catalyst design.

ML Algorithms in Action: Techniques for Predicting Activity and Optimizing Catalysts

Accurately predicting catalytic descriptors with machine learning (ML) is paramount for accelerating catalyst design. The cornerstone of developing a universal, efficient, and accurate ML model is a unique representation of a system's atomic structure. Such representations must be applicable across a wide material domain, easily computable, and, crucially, capable of resolving the similarity and dissimilarity between atomic structures, a key challenge in complex catalytic systems ranging from simple adsorbates on pure metals to highly disordered high-entropy alloys and supported nanoparticles [21]. This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for generating and utilizing these atomic structure descriptors, framed within the broader objective of advancing machine learning for catalytic activity prediction.

Quantifying Descriptor Performance Across Catalytic Systems

The predictive performance of ML models is highly dependent on the chosen atomic structure representation and the complexity of the catalytic system. The following table summarizes the performance, quantified by Mean Absolute Error (MAE), of various models and representations across different system complexities.

Table 1: Performance of Structure Representations and ML Models on Various Catalytic Systems

| Catalytic System | Description / Adsorbate | ML Model / Representation | Key Performance Metric (MAE) | Reference / Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ordered Surfaces (Monodentate) | Atomic Carbon (Cads Dataset) | RFR (Basic Features) | 0.346 eV | [21] |

| Atomic Carbon (Cads Dataset) | RFR (Features + Coordination Numbers) | 0.186 eV | [21] | |

| Atomic Carbon (Cads Dataset) | GAT-w/oCN (Connectivity-based) | 0.162 eV | [21] | |

| Atomic Carbon (Cads Dataset) | GAT-wCN (Connectivity-based + CN) | 0.128 eV | [21] | |

| 3-fold Hollow Sites (Cads Dataset) | GAT-w/oCN (All training data) | 0.11 eV (Training MAE) | [21] | |

| Complex Catalytic Systems | Metallic Interfaces (Various) | Equivariant GNN (equivGNN) | < 0.09 eV for different descriptors | [21] |

| 11 Diverse Adsorbates | DOSnet (with ab initio features) | 0.10 eV | [21] | |

| CO* and H* | CGCNN / SchNet (with non-ab initio features) | 0.116 eV / 0.085 eV | [21] |

Protocol: Developing an ML Model for Catalytic Descriptor Prediction

This protocol outlines the key steps for developing a machine learning model to predict binding energies and other catalytic descriptors from atomic structures.

Materials and Computational Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ML in Catalysis

| Item / Reagent | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Generates high-quality training data (e.g., binding energies) for the ML model. Considered the computational equivalent of an experimental assay. | Used to calculate target properties for datasets like the Cads Dataset [21]. |

| Atomic Structure Representation | Converts the 3D atomic configuration into a numerical input for the ML model. This is the foundational "feature set." | Ranges from simple features (element type) to complex graph structures [21]. |

| Site Representation (with CN) | A specific representation that includes atomic numbers and coordination environments. | Improved RFR model MAE from 0.346 eV to 0.186 eV [21]. |

| Connectivity-Based Graph | Represents the atomic structure as a graph (nodes=atoms, edges=bonds) for graph neural networks. | Used as input for GAT models; requires enhancement to resolve chemical-motif similarity [21]. |

| Equivariant Graph Neural Network (equivGNN) | The ML model architecture that learns from graph-structured data while respecting physical symmetries. | The final model achieving high accuracy across diverse systems [21]. |

| Random Forest Regression (RFR) | A robust machine learning algorithm suitable for initial benchmarking with hand-crafted features. | Used to evaluate the importance of different representation levels [21]. |

Step-by-Step Experimental Methodology

Dataset Curation and Generation

- Objective: Assemble a set of atomic structures with their corresponding target properties (e.g., binding energies from DFT).

- Procedure: Perform high-throughput DFT calculations for a representative set of catalytic systems relevant to your research (e.g., monodentate adsorbates on alloy surfaces, complex bidentate motifs, HEA surfaces).

- Output: A curated dataset, such as the Cads Dataset used in the referenced study [21].

Atomic Structure Representation and Feature Engineering

- Objective: Convert each atomic structure in the dataset into a numerical representation.

- Procedure: a. Begin with simple site representations: Use basic features like elemental properties. b. Incorporate local environment descriptors: Add coordination numbers (CNs) for each atom, which has been shown to significantly improve performance [21]. c. Advance to graph-based representations: Represent the entire adsorption motif as a graph. Use atomic numbers as node features. For edges, start with a connectivity-based method (i.e., define edges based on atomic bonds).

- Output: A dataset of feature vectors or graph objects ready for ML model training.

Model Training, Validation, and Benchmarking

- Objective: Train and evaluate the performance of different ML models.

- Procedure: a. Benchmark with simpler models: Use a model like Random Forest Regression (RFR) with the site representations from Step 2a and 2b to establish a baseline performance. b. Progress to Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Train a Graph Attention Network (GAT) or similar GNN on the graph-based representations from Step 2c. c. Implement an Equivariant GNN (equivGNN): To achieve state-of-the-art performance and handle complex systems, develop or employ an equivariant GNN model. This model uses enhanced message-passing to create robust representations that can distinguish subtle chemical-motif similarities [21]. d. Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold CV) to ensure robust performance metrics and avoid overfitting.

- Output: Trained ML models with validated performance metrics (e.g., MAE).

Model Deployment and Prediction

- Objective: Use the trained model to predict descriptors for new, unknown catalytic systems.

- Procedure: Feed the atomic structure representation of the new system into the trained model (e.g., the equivGNN) to obtain a prediction for the binding energy or other catalytic descriptors.

- Output: Predicted catalytic descriptors for novel materials, enabling high-throughput computational screening.

Visualizing the Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for developing the ML model, from data generation to prediction, as described in the protocol.

Visualizing the Evolution of Atomic Structure Representations

The complexity of the atomic structure representation directly impacts the model's ability to resolve chemical-motif similarity. This evolution is summarized in the following diagram.

The integration of machine learning (ML) into the realm of organometallic catalysis represents a paradigm shift in how researchers approach catalyst design and reaction optimization. This is particularly true for the prediction of enantioselectivity and reaction yields, properties central to the synthesis of chiral pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals. Where traditional methods rely on labor-intensive experimental screening or computationally expensive quantum mechanics, ML offers a powerful, data-driven alternative. This case study, framed within broader thesis research on ML for catalytic activity prediction, examines the practical application of machine learning models to forecast complex catalytic outcomes, detailing specific protocols, key reagents, and data interpretation methods for research scientists.

Machine Learning Approaches in Catalysis: A Comparative Analysis

The application of ML in catalysis spans various model types and featurization strategies, each with distinct advantages. The table below summarizes the performance of different ML approaches as demonstrated in recent case studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Machine Learning Models for Predicting Catalytic Properties

| Catalytic System | ML Task | ML Model(s) Used | Key Descriptors/Features | Reported Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pd-catalyzed asymmetric β-C–H bond activation | Enantioselectivity (% ee) prediction | Deep Neural Network (DNN) | Molecular descriptors from a metal-ligand-substrate complex | RMSE of 6.3 ± 0.9% ee on test set; demonstrated high generalizability to other reactions. | [22] |

| Magnesium-catalyzed epoxidation & thia-Michael addition | Enantioselectivity (ee) prediction from small datasets | Multiple models evaluated | Curated experimental parameters and molecular descriptors | Best model achieved R² ~0.8; successful generalization to untested substrates. | [23] |

| Amidase-catalytic enantioselectivity | Classification of high/low enantioselectivity | Random Forest (RF) Classifier | Substrate "chemistry" (functional groups) and "geometry" (3D structure) descriptors | High F-score (>0.8) for classifying reactions with ee ≥ 90%. | [24] |

| Chiral Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs) for HER | Evaluation and prediction of HER performance | SISSO (Sure Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator) | Spatial and chiral effects from DFT calculations | Identified interpretable descriptors linking chirality to enhanced HER activity. | [25] |

| Generative catalyst design (CatDRX) | Catalyst generation & yield prediction | Reaction-conditioned Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | Structural representations of catalysts and reaction components | Competitive performance in yield prediction and novel catalyst generation. | [8] |

A critical step in building these models is the conversion of chemical structures into a numerical format that the algorithm can process, known as featurization or molecular representation. The choice of representation significantly impacts model performance and interpretability.

Table 2: Common Molecular Representation Strategies in Catalytic ML

| Representation Type | Description | Application Example | Advantages | Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Organic Descriptors | Pre-defined parameters like Sterimol values, NBO charges, HOMO/LUMO energies. | Multivariate linear regression models for enantioselectivity. | Chemically intuitive, directly related to mechanism. | Not easily transferable; requires redefinition for new systems. | [26] |

| Atomic-Centered Symmetry Functions (ACSFs) | Histograms describing the 3D atomic environment around each atom. | Random forest model for amidase enantioselectivity. | Captures complex 3D geometry; generalizable. | Requires geometry optimization; less chemically transparent. | [24] |

| Reaction-Based Representations | Representations encoding the 3D structure of key reaction intermediates or transition states. | Predicting DFT-computed ee in organocatalysis from intermediate structures. | Incorporates mechanistic insight; high accuracy. | Dependent on the identification of a relevant mechanistic species. | [26] |

| SLATM (Spectral London and Axilrod-Teller-Muto) | A comprehensive representation composed of two- and three-body potentials from atomic coordinates. | Quantum Machine Learning (QML) for predicting activation energies. | Physics-based; offers a good balance of accuracy and cost. | Computationally intensive to generate. | [26] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a DNN Model for Enantioselectivity Prediction in C–H Activation

This protocol is adapted from Hoque and Sunoj's work on Pd-catalyzed β-C–H functionalization [22].

1. Data Curation and Dataset Construction

- Source: Manually curate a dataset from published literature. The exemplary study used 240 unique catalytic reactions.

- Data Points: For each reaction, record the chiral ligand, substrate, coupling partner, catalyst precursor, additive, base, solvent, temperature, and the experimentally measured enantiomeric excess (% ee).

- Key Consideration: Ensure diversity in reaction components to build a robust model. The dataset contained 77 unique chiral ligands and 51 unique coupling partners.

2. Choice of Featurization Strategy

- Structurally-Based Featurization: Instead of featurizing individual components, select a mechanistically relevant species. For C–H activation, the metal-ligand-substrate complex prior to the enantiodetermining step is ideal.

- Descriptor Generation:

- Generate a reasonable 3D geometry for this complex for each reaction in the dataset.

- Use quantum chemistry software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA) for geometry optimization at a low-cost level (e.g., DFTB) if necessary.

- Calculate a set of molecular descriptors (e.g., steric, electronic, topological) from the optimized structure. Software like DRAGON or RDKit can be used.

3. Model Training and Validation

- Data Splitting: Split the dataset into training (~80%) and test (~20%) sets. Use stratified splitting to ensure the ee distribution is similar in both sets.

- Model Architecture: Implement a Deep Neural Network (DNN). A typical architecture may include:

- An input layer matching the number of descriptors.

- 2-4 hidden layers with activation functions like ReLU or Tanh.

- A linear output layer for regression (% ee prediction).

- Training: Use a loss function like Mean Squared Error (MSE) and an optimizer like Adam. Perform hyperparameter tuning (learning rate, layers, nodes) via cross-validation.

- Validation: Evaluate the final model on the held-out test set. The exemplary study achieved an RMSE of 6.3 ± 0.9% ee [22].

Workflow for building a DNN model to predict enantioselectivity in C–H activation reactions.

Protocol 2: Random Forest Classification for Biocatalytic Enantioselectivity

This protocol is based on the work by Li et al. for predicting amidase enantioselectivity [24].

1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

- Source: Collect a dataset of reactions with known enantioselectivity outcomes. The exemplary study used 240 substrates.

- Output Standardization: Convert all enantioselectivity data (ee of product or recovered substrate) into the enantiomeric ratio (E value) and subsequently into the free energy difference:

ΔΔG‡ = -RT ln E. - Classification: Define a classification threshold based on

-ΔΔG‡. For example, samples with-ΔΔG‡ ≥ 2.40 kcal/mol(corresponding to ee ≥ 90% at 303 K) are classed as "positive" (high enantioselectivity), and the rest as "negative".

2. Feature Calculation and Selection

- Descriptor Types: Calculate two types of descriptors for each substrate:

- Chemistry Descriptors: Based on functional group "cliques" derived from the 2D molecular structure.

- Geometry Descriptors: Atomic-Centered Symmetry Functions (ACSFs) obtained from the 3D optimized geometry of the substrate.

- Feature Selection: Perform a feature selection process (e.g., based on variance or correlation) to reduce dimensionality and prevent overfitting.

3. Model Building and Evaluation

- Algorithm: Train a Random Forest (RF) Classifier. RF is robust against overfitting and works well on small-to-medium-sized datasets.

- Validation: Use 5-fold cross-validation on the training set to tune hyperparameters (e.g., number of trees, tree depth).

- Performance Metrics: Evaluate the model on the test set using Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F-score, and AUC (Area Under the ROC Curve). The exemplary model achieved an F-score above 0.8 [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Driven Catalysis Research

| Reagent / Software Solution | Function / Purpose | Example in Use | Considerations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) | Performing Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations for descriptor generation and validation. | Used to calculate formation energies and spin densities of chiral single-atom catalysts. | Provides high-quality electronic structure data; computationally intensive. | [25] |

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit for calculating molecular descriptors and fingerprinting. | Generating 2D molecular descriptors for machine learning input. | Versatile and programmable; integral to many ML workflows in chemistry. | [26] [24] |

| Scikit-learn | Python library providing efficient tools for machine learning and statistical modeling. | Implementing Random Forest, SVM, and other classifiers/regressors. | Accessible for beginners with comprehensive algorithms; requires coding knowledge. | [24] |

| Gaussian 09/16 | Quantum chemistry software package for molecular geometry optimization and property calculation. | Optimizing 3D geometries of substrates for calculating geometry-based descriptors. | Industry standard for accurate quantum chemical calculations; commercial license required. | [24] |

| SISSO (Sure Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator) | A compressed-sensing method for identifying optimal descriptive parameters from a huge feature space. | Identifying interpretable descriptors linking chirality to HER activity from DFT data. | Powerful for model interpretation and descriptor identification; mathematically complex. | [25] |

Visualization of Chirality Effects in Catalysis

The study of chiral single-atom catalysts (SACs) provides a clear example of how ML can decode complex structure-property relationships. Song et al. used DFT and ML to show that chirality in carbon nanotube-based SACs significantly enhances Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER) activity [25]. The CISS effect causes a broken symmetry in the spin density distribution around the catalytic metal center (e.g., In, Sb, Bi). This asymmetry facilitates more efficient electron transfer, a key descriptor in the resulting ML model, thereby boosting catalytic activity. Right-handed M–N-SWCNT(3,4) structures were found to particularly benefit from this effect.

Logical relationship between chirality and enhanced catalytic activity through the CISS effect.

This case study demonstrates that machine learning is no longer a futuristic concept but a practical, powerful tool for addressing central challenges in organometallic catalysis. By leveraging well-curated datasets, informative molecular representations, and robust modeling protocols, researchers can now predict enantioselectivity and yields with remarkable accuracy, thereby streamlining the catalyst design cycle. The integration of ML with computational chemistry and experimental validation creates a virtuous cycle of discovery, promising to significantly accelerate the development of new catalytic transformations for the synthesis of complex molecules, especially in the pharmaceutical and fine chemical industries. Future directions will involve the wider adoption of generative models for de novo catalyst design and a greater emphasis on extracting chemically interpretable insights from complex ML models.

In enzyme research, a significant gap has persisted between computational tools that predict what reaction an enzyme catalyzes and those that identify where the catalysis occurs. This fragmentation severely limits our ability to fully characterize enzymatic function, particularly for unannotated proteins or complexes with quaternary structures [27]. The Catalytic Activity and site Prediction and Inalysis tool in Multimer proteins (CAPIM) addresses this critical need by integrating binding pocket identification, catalytic residue annotation, and functional validation into a unified, automated pipeline [27] [28].

CAPIM's development is situated within the broader paradigm shift in catalytic science, where machine learning (ML) is evolving from a purely predictive tool into a theoretical engine for mechanistic discovery [15]. By combining the capabilities of three established tools—P2Rank, GASS, and AutoDock Vina—CAPIM bridges the long-standing divide between residue-level annotation and functional characterization, providing a powerful resource for drug discovery and protein engineering [27].

Core Components and Workflow of the CAPIM Pipeline

The CAPIM pipeline integrates specialized computational tools into a coordinated workflow that transforms a protein structure input into validated functional predictions. Its architecture is designed to overcome the limitations of single-purpose tools by combining complementary analytical approaches.

Integrated Tools and Their Functions

Table 1: Core Computational Components of the CAPIM Pipeline

| Tool | Primary Function | Methodological Approach | Role in CAPIM |

|---|---|---|---|

| P2Rank | Binding pocket prediction | Machine learning (Random Forest) using physicochemical, geometric, and statistical features [27] | Identifies potential ligand-binding pockets on protein structures without requiring structural templates [27] |

| GASS | Catalytic residue identification & EC number annotation | Genetic algorithm-based structural template matching with non-exact amino acid matches [27] | Annotates catalytically active residues and assigns Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers across protein chains [27] |

| AutoDock Vina | Functional validation via substrate docking | Energy-based docking scoring binding affinity using hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic contacts, and van der Waals forces [27] | Validates predicted catalytic sites by assessing substrate binding affinity and spatial compatibility [27] |

Integrated Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the coordinated flow of data and analyses through the CAPIM pipeline:

Key Technological Advantages

CAPIM introduces several technological innovations that address critical limitations in existing tools:

- Multimeric Support: Unlike many structure-based tools restricted to single polypeptide chains, CAPIM supports any number of peptide chains in protein complexes, enabling analysis of enzymatic functions dependent on quaternary structures [27].

- Residue-Level Functional Annotation: By merging P2Rank's spatial predictions with GASS's functional templates, CAPIM generates residue-level activity profiles within predicted pockets, connecting structural features directly to mechanistic function [27].

- Template-Free and Template-Based Integration: The combination of P2Rank's template-free, machine learning approach with GASS's template-based method creates a complementary system that balances novelty detection with known catalytic motif recognition [27].

Performance and Validation

CAPIM has demonstrated robust performance through comprehensive case studies involving both well-characterized enzymes and unannotated multi-chain targets [27]. While the developers note that their aim is "not to outperform existing specialized EC predictors," but rather to provide residue-level functional annotation and binding site validation, the pipeline successfully bridges the critical gap between catalytic residue identification and functional annotation [27].

Comparative Performance Metrics

Table 2: Performance Assessment of CAPIM Component Technologies

| Tool/Component | Validation Method | Reported Performance | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GASS | Validation against Catalytic Site Atlas (CSA) | Correctly identified >90% of catalytic sites in multiple datasets [27] | Ranked 4th among 18 methods in CASP10 substrate-binding site competition [27] |

| P2Rank | Benchmarking against other pocket prediction tools | High-accuracy prediction through ML-based feature evaluation [27] | Used as reference grid for docking analysis within CAPIM [27] |

| AutoDock Vina | Binding pose and affinity prediction | Energy-based scoring accounting for key molecular interactions [27] | Provides quantitative measures of binding affinity and spatial compatibility [27] |

The utility of the integrated CAPIM pipeline is particularly evident for complex multimeric targets where traditional tools fail. By supporting analysis of polymeric structures such as amyloids, CAPIM enables investigations into enzymatic functions that emerge only at the quaternary structure level [27].

Experimental Protocol for CAPIM Implementation

This section provides a detailed methodology for implementing the CAPIM pipeline, from initial setup to result interpretation.

System Requirements and Installation

CAPIM is available both as a standalone application and as a hosted web service:

- Web Service: Accessible at

https://capim-app.serve.scilifelab.sefor users preferring a browser-based interface [27] - Standalone Application: Available at

https://git.chalmers.se/ozsari/capim-appfor local installation [27] - System Requirements: The pipeline has no limitation on the number of peptide chains analyzed, making it suitable for larger polymeric protein structures [27]

Input Preparation and Processing

Input Requirements:

- Protein structure files in PDB format

- For docking validation: user-defined ligand structures in appropriate chemical format

- Default parameters are provided for all components, with advanced options for customization

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Structure Preparation

- Obtain protein structure through experimental methods or homology modeling

- Ensure proper protonation states and structural integrity

- For multimeric proteins, include all relevant chains in the input file

Pipeline Execution

- Submit structure to CAPIM via web interface or command line

- P2Rank automatically identifies potential binding pockets using its machine learning approach [27]

- GASS concurrently identifies catalytically active residues using genetic algorithms and assigns EC numbers [27]

- The system merges outputs to generate residue-level activity profiles

Functional Validation

- Prepare substrate ligand files for docking validation

- Define docking grid based on P2Rank predictions

- Execute AutoDock Vina to assess binding affinity and spatial compatibility [27]

- Analyze docking poses and affinity scores to validate predicted catalytic function

Result Interpretation and Analysis

Key Outputs:

- Identified binding pockets with confidence scores

- Annotated catalytic residues with associated EC numbers

- Residue-level activity profiles connecting spatial predictions to functional annotations

- Docking results with binding affinities and interaction models

Validation Criteria:

- Consistency between predicted pockets and annotated catalytic residues

- Agreement between EC number assignments and docking results

- Structural plausibility of catalytic residue arrangements

- Comparative analysis with known enzymatic functions when available

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of integrated prediction pipelines requires specific computational resources and analytical components.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Catalytic Activity Prediction

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specialized Prediction Tools | P2Rank | Machine learning-based binding pocket identification using physicochemical and geometric features [27] | Template-free prediction of potential ligand binding sites |

| GASS (Genetic Active Site Search) | Identifies catalytic residues across protein chains and assigns EC numbers through structural template matching [27] | Functional annotation of catalytic activity beyond single-chain limitations | |

| Validation Resources | AutoDock Vina | Energy-based docking to validate substrate binding in predicted active sites [27] | Functional validation of predicted catalytic sites through binding affinity assessment |

| Reference Databases | Catalytic Site Atlas (CSA) | Reference database of catalytic residues for validation studies [27] | Benchmarking tool performance against known catalytic sites |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Source of protein structures for analysis and template identification [27] | Essential structural repository for input data and comparative analyses |

CAPIM represents a significant advancement in computational enzymology by integrating disparate analytical capabilities into a unified framework. By combining binding pocket identification, catalytic site annotation, and functional validation, it addresses the critical gap between residue-level annotation and functional characterization that has long limited computational enzyme research [27].

The pipeline's support for multimeric proteins extends its utility to complex biological systems that were previously difficult to analyze with conventional tools. As machine learning continues to transform catalytic science from trial-and-error approaches to principled prediction [15], integrated frameworks like CAPIM will play an increasingly vital role in accelerating drug discovery and protein engineering applications.

For researchers investigating enzymatic function, particularly for uncharacterized proteins or complex multimeric assemblies, CAPIM offers a powerful hypothesis-generation tool that bridges structural bioinformatics with functional mechanism analysis. Its development marks an important step toward comprehensive computational characterization of enzymatic function across the proteome.

Navigating Pitfalls: Overcoming Data Scarcity, Overfitting, and Model Interpretability

In machine learning for catalytic activity prediction, data quality is not merely a convenience—it is the fundamental foundation upon which reliable, accurate, and interpretable models are built. High-quality data ensures that models are trained on accurate and representative samples, which directly impacts performance, generalizability to unseen data, and the trustworthiness of predictions [29]. The presence of noisy data—containing inaccuracies, errors, or inconsistencies—and the challenge of small datasets—containing insufficient samples for robust model training—represent significant hurdles that can obscure underlying patterns and lead to inaccurate predictions and misguided scientific conclusions [30] [31]. In critical sectors, decisions based on faulty data can trigger costly miscalculations. This document outlines detailed application notes and protocols to overcome these data quality challenges, specifically framed within catalytic activity prediction research.

The tables below summarize the core challenges and the corresponding strategic approaches for handling small and noisy datasets in catalysis informatics.

Table 1: Taxonomy of Data Quality Issues and Their Impact on Catalysis ML Models

| Data Issue Type | Definition & Examples | Impact on Catalytic Model Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Noisy Data [30] [31] | Errors, inconsistencies, or irrelevant information. Includes random noise (sensor fluctuations), systematic noise (faulty instrument calibration), and outliers (data points far from the expected range). | Obscures true structure-activity relationships, reduces predictive accuracy, leads to models that learn incorrect patterns and fail to generalize [31]. |

| Small Datasets [32] | Insufficient data samples for the machine learning model to learn effectively. A common issue in high-throughput catalytic experimentation and specialized catalyst studies. | Models are prone to overfitting, where they memorize the training data instead of learning generalizable patterns, resulting in poor performance on new, unseen catalysts [32]. |

| Incomplete Data [33] | Missing feature values or labels (e.g., unmeasured adsorption energies, missing process conditions from experimental records). | Introduces bias, complicates the use of many standard ML algorithms, and can lead to incomplete understanding of catalytic descriptor importance. |

Table 2: Strategic Framework for Mitigating Data Quality Issues

| Core Challenge | Primary Strategy | Key Techniques & Algorithms |

|---|---|---|

| Noisy Data | Data Cleaning & Robust Model Selection [30] [31] | Statistical outlier detection (Z-scores, IQR), smoothing (moving averages), automated anomaly detection (Isolation Forest, DBSCAN), and using noise-robust algorithms like Random Forests [30] [31]. |

| Small Datasets | Data Augmentation & Efficient Model Design [32] | Feature engineering and selection [14], transfer learning, and employing specialized methods like few-shot learning [32]. |

| Incomplete Data | Data Imputation [30] [33] | Employing techniques such as mean/mode imputation or more advanced methods like K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) imputation to address missing data points [30] [33]. |

Experimental Protocols for Data Handling

Protocol 1: Handling Noisy Data in Catalytic Descriptor Sets

This protocol is designed to identify and remediate noise within datasets containing catalytic descriptors, such as those derived from experimental conditions, catalyst properties, or theoretical calculations.

3.1.1 Materials and Reagents

- Software Environment: Python 3.8+ with key libraries: pandas for data manipulation, scikit-learn for imputation and model building, and NumPy for numerical operations [30] [29].

- Input Data: A dataset of catalytic experiments, typically in CSV format, containing columns for various descriptors (e.g., ionic radius, electronegativity, heat of formation of oxides [14]) and target properties (e.g., faradaic efficiency, selectivity).

3.1.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Noise Identification:

- Visual Inspection: Generate visualizations including box plots to identify outliers in descriptor distributions and scatter plots to spot anomalies in bivariate relationships [30] [31].

- Statistical Methods: Calculate Z-scores or use the Interquartile Range (IQR) method to flag data points that deviate significantly from the mean. Data points with Z-scores beyond ±3 or those falling outside 1.5 times the IQR are typically considered outliers [30] [31].

- Domain Expertise Consultation: Critically review flagged data points with catalysis experts to distinguish between genuine measurement errors and valid, rare catalytic phenomena [31].

Data Cleaning and Imputation:

- Correct Errors: Fix typos and ensure consistent formatting of categorical data (e.g., catalyst names) using simple replacement functions [30].

- Handle Missing Values: Use imputation to fill missing descriptor values. The choice of method should depend on the nature of the data [30] [33].

- Remove Duplicates: Identify and remove duplicate experimental entries to prevent bias in the model [30] [29].

Data Transformation:

- Smoothing: For continuous data or time-series trends (e.g., catalyst deactivation profiles), apply smoothing techniques like moving averages to reduce short-term fluctuations [30].

- Feature Scaling: Scale features to a similar range to prevent models from being skewed by descriptors with large variances. Standardization is a common technique [30].

Protocol 2: Knowledge Extraction from Small Catalytic Datasets

This protocol outlines a methodology for maximizing information gain from a limited set of catalytic experiments, inspired by iterative learning approaches used in catalyst design [14].

3.2.1 Materials and Reagents

- Feature Engineering Tools: Libraries for molecular featurization (e.g., for organic additives [14]) and domain knowledge for creating descriptive features.

- ML Algorithms: Tree-based models (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost) are particularly effective for small datasets and provide inherent feature importance analysis [14].

3.2.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Intelligent Feature Engineering:

- Go beyond raw data by creating meaningful descriptors. For example, in a study on Cu catalysts for CO₂RR, the presence or absence of specific metal salts or functional organic groups in a catalyst recipe were used as initial binary (one-hot) descriptors [14].

- Leverage domain knowledge to create descriptors that capture critical physicochemical properties or structural motifs.

Iterative Learning and Feature Refinement:

- Round 1: Initial Analysis. Train a model (e.g., Random Forest) using the initial descriptor set. Perform descriptor importance analysis to identify the most critical features influencing the target catalytic property (e.g., faradaic efficiency for C₂⁺ products) [14].

- Round 2: Descriptor Enrichment. Refine the critical features identified in Round 1. For organic molecules, this could involve transforming the local molecular structure into a more detailed feature matrix using molecular fragment featurization (MFF) [14]. Repeat model training and importance analysis on this enriched set.

- Round 3: Synergistic Effects. Use techniques like "random intersection trees" to examine important variable combinations that have positive or negative synergistic effects on catalytic performance [14].

Model Validation for Small Data:

- Employ rigorous validation techniques like leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) to assess the model's performance and generalizability more reliably when data is scarce [34].

- Use the insights from the iterative learning process to guide the design of a minimal set of high-value validation experiments, effectively expanding the dataset with strategically chosen data points.

Workflow Visualizations

Noisy Data Management Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and decision points for identifying and handling noisy data in catalytic datasets.

Noisy Data Management Workflow

Small Dataset Knowledge Extraction

This workflow depicts the iterative paradigm for extracting maximum knowledge from a limited number of catalytic experiments.

Small Dataset Knowledge Extraction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational and Data Tools for Catalysis Informatics

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Data Handling |

|---|---|---|

| pandas (Python Library) [30] [29] | Software Library | Core data structure (DataFrame) for manipulation, cleaning (e.g., drop_duplicates(), dropna()), and transformation of tabular catalytic data. |

| scikit-learn (Python Library) [30] [29] | Software Library | Provides a unified interface for imputation (SimpleImputer, KNNImputer), feature scaling (StandardScaler), model training, and validation (cross-validation). |

| Isolation Forest Algorithm [31] | Algorithm | An unsupervised method for anomaly detection in high-dimensional datasets, useful for identifying outliers in complex descriptor spaces. |

| Random Forest / XGBoost [14] | Algorithm | Tree-based ensemble models robust to noise and effective for small datasets; provide native feature importance scores for descriptor analysis. |