Metal-Based vs. Carbon-Based Catalysts for Biomass Gasification: A Comprehensive Review of Performance, Optimization, and Future Directions

This article provides a systematic comparison of metal-based and carbon-based catalysts for biomass gasification, targeting researchers and scientists in sustainable energy and biofuel development.

Metal-Based vs. Carbon-Based Catalysts for Biomass Gasification: A Comprehensive Review of Performance, Optimization, and Future Directions

Abstract

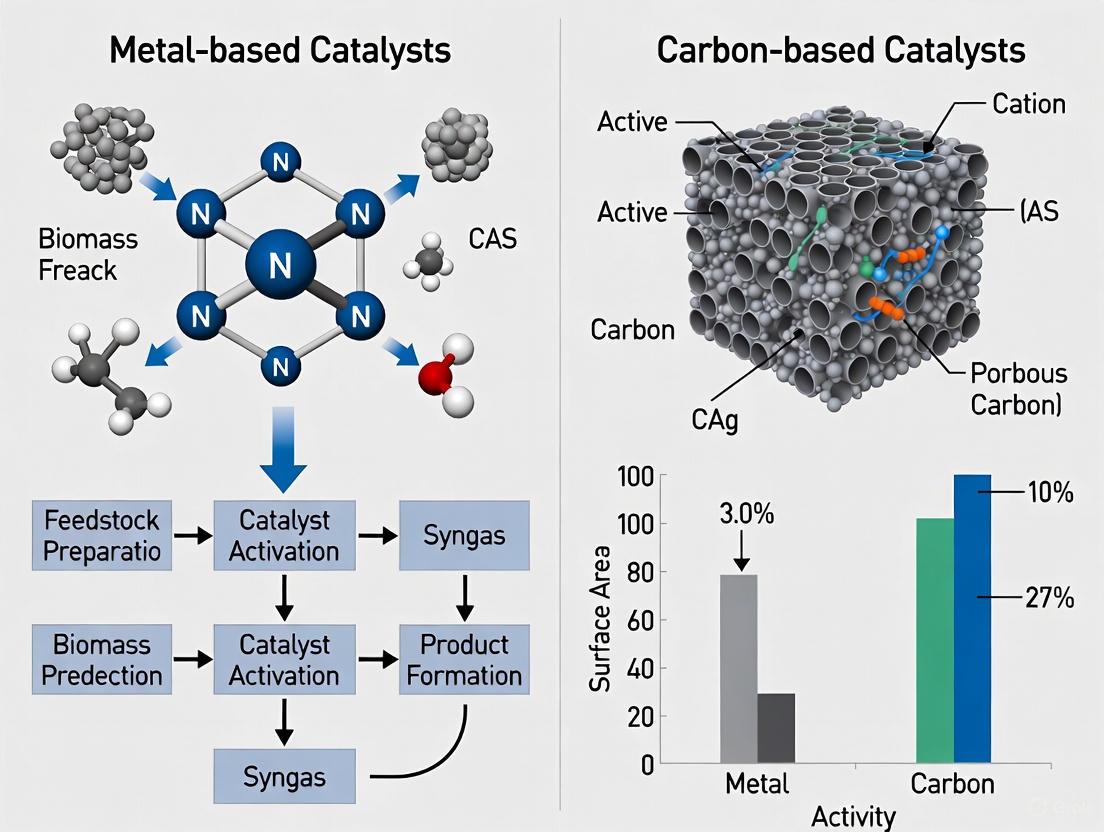

This article provides a systematic comparison of metal-based and carbon-based catalysts for biomass gasification, targeting researchers and scientists in sustainable energy and biofuel development. It explores the fundamental characteristics, catalytic mechanisms, and operational roles of both catalyst classes in key reactions like tar reforming and hydrogen production. The content covers advanced optimization strategies to combat catalyst deactivation, process integration techniques for enhanced efficiency, and a critical validation of performance through experimental data and sustainability metrics. By synthesizing the latest research, this review aims to guide the selection and development of robust, cost-effective catalysts for advancing carbon-neutral biorefining and sustainable fuel production.

Understanding Catalyst Fundamentals: Composition, Mechanisms, and Roles in Gasification

Biomass gasification represents a pivotal technology for sustainable energy and chemical production, transforming diverse biomass feedstocks into valuable syngas (CO + H2), a key precursor for fuels, chemicals, and power generation [1]. The efficiency and product quality of this process are critically dependent on catalyst performance, particularly in addressing the significant challenge of tar formation. Tars are complex, recalcitrant mixtures of hydrocarbons formed during gasification that cause operational issues such as equipment clogging and corrosion, while also degrading process efficiency and gas quality [1] [2]. Catalytic intervention is essential not only for tar abatement but also for enhancing gas yields, particularly hydrogen, and facilitating desirable shifts in gas composition [1].

Within this context, metal-based catalysts are extensively employed to catalyze key reactions including tar cracking/reforming, water-gas shift, and methane reforming. These catalysts can be broadly categorized into two groups: transition metals (such as Ni, Co, and Fe) and noble metals (including Pt, Pd, and Ru). This guide provides a objective comparison of these two catalyst classes, framing their performance within the broader research on metal-based versus carbon-based catalysts for biomass gasification. The comparison focuses on their activity, selectivity, resistance to deactivation, and cost-effectiveness, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies.

Fundamental Characteristics and Mechanisms

Transition metal catalysts, particularly those based on nickel (Ni), iron (Fe), and cobalt (Co), are widely utilized in biomass gasification due to their high catalytic activity for C-C bond cleavage and reforming reactions at a relatively lower cost compared to noble metals [3]. Their performance is often modulated by forming alloys or bimetallic systems; for example, the addition of Fe to Ni catalysts increases lattice oxygen content, which enhances carbon resistance by facilitating the removal of carbon deposits through oxidation [2]. The outermost electronic structure of Ni is similar to that of Pt, contributing to its good catalytic activity for steam reforming and methane decomposition [3].

Noble metal catalysts, including ruthenium (Ru), platinum (Pt), and palladium (Pd), are recognized for their superior catalytic activity and high resistance to poisoning [4] [5]. They often exhibit excellent performance at lower temperatures and demonstrate higher tolerance to carbon deposition (coking) and thermal sintering. Their activity is frequently enhanced by strong metal-support interactions (SMSIs) and the formation of alloyed structures, as seen in Ru-Ni architectures that synergistically suppress coke deposition and enhance hydrogen selectivity [1]. The interaction between the noble metal and its support, such as Pt with TiO2 or CeO2, plays a critical role in determining its overall activity and stability [5].

Quantitative Performance Comparison Table

The following table summarizes key performance metrics for transition and noble metal catalysts based on experimental studies from the literature.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Transition Metal and Noble Metal Catalysts

| Catalyst Type | Specific Example | Reaction Conditions | Tar Conversion (%) | H₂ Selectivity / Yield | Stability & Deactivation Resistance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal (Ni-Fe) | Ni₃-Fe₁/Al₂O₃ | Plasma-catalytic CO₂ reforming of toluene, 250°C | >90% (Toluene conversion) | High syngas (H₂+CO) selectivity | High carbon resistance due to strong basicity and redox capacity | [2] |

| Transition Metal (Ni) | Ni-Ce@SiC | Microwave-assisted cracking | >90% | Not Specified | 30% reduction in coke formation vs. conventional heating | [1] |

| Noble Metal (Ru) | Ru/Al₂O₃ | Toluene hydrogenation in liquid phase | High hydrogenation activity | Effective for hydrodearomatization | Performance affected by reduction procedure and oxide formation | [4] |

| Noble Metal (Pt) | Pt/TiO₂ | CO oxidation | Not Applicable (CO oxidation) | Not Applicable (CO oxidation) | 100% CO conversion at 100°C | [5] |

| Noble Metal (Pd) | Pd/CeO₂ | CO oxidation | Not Applicable (CO oxidation) | Not Applicable (CO oxidation) | 100% CO conversion at 150°C | [5] |

| Bimetallic (Noble-Transition) | Ru-Ni Alloy | Tar steam reforming | Not Specified | Enhanced hydrogen selectivity | Synergistically suppresses coke deposition | [1] |

Cost-Benefit Analysis Table

Beyond pure performance, the economic feasibility of catalysts is a critical factor for industrial application.

Table 2: Economic and Practical Considerations of Metal Catalysts

| Factor | Transition Metals (Ni, Fe, Co) | Noble Metals (Pt, Pd, Ru) |

|---|---|---|

| Raw Material Cost | Low cost and abundantly available [3]. | High cost due to scarcity and limited global supply [5]. |

| Primary Advantages | High activity for C-C bond breaking (Fe) [3]; good catalytic activity (Ni) [3]. | Excellent low-temperature activity, high stability, and superior resistance to poisoning [4] [5]. |

| Common Deactivation Issues | Prone to deactivation by coking and sintering [2] [3]. | Generally more resistant to carbon deposition and sintering [1]. |

| Regeneration Potential | Can be regenerated but may suffer from irreversible sintering. | Often maintain better dispersion and activity after regeneration cycles. |

| Ideal Application Context | Large-scale, cost-sensitive industrial gasification processes. | Applications requiring high stability, low-temperature operation, or where poisoning is a major concern. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Representative Experimental Protocol: Ni-Fe/Al₂O₃ Catalyst Testing

To illustrate the methodology behind generating such performance data, the following workflow details a standard protocol for preparing and evaluating a bimetallic transition metal catalyst, as used in recent research on plasma-catalytic CO₂ reforming of tar [2].

Diagram 1: Catalyst Preparation and Testing Workflow

Step 1: Catalyst Synthesis via Wet Impregnation

- Procedure: The catalyst is prepared using wet impregnation. Aqueous solutions of metal precursors (e.g., RuCl₃·xH₂O, PdCl₂, PtCl₂ for noble metals; Ni and Fe nitrates for transition metals) are used to impregnate the support material, typically γ-Al₂O₃ [4] [2]. The suspension is stirred continuously at a defined temperature and pH to ensure uniform dispersion of metal precursors on the support surface.

Step 2: Reduction and Activation

- Procedure: The impregnated solid is subjected to a reduction process to convert metal salts into their active metallic states. This can be done using liquid reducing agents like formaldehyde (H₂CO) or sodium borohydride (NaBH₄) under mild conditions, or via ex situ reduction under a H₂ flow at high temperatures (e.g., 500°C for 2 hours) [4] [2]. The reduction method significantly impacts metal dispersion and final catalytic activity.

Step 3: Catalyst Characterization

- Crystalline Structure: X-ray diffraction (XRD) is used to identify crystalline phases, metal oxides, and alloy formation [2].

- Texture Properties: N₂ adsorption-desorption analysis (BET method) determines surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution. Catalysts like Nix-Fey/Al₂O₃ typically exhibit type IV isotherms, indicating mesoporous structures [2].

- Morphology and Dispersion: Techniques like scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) are employed to visualize catalyst morphology, metal particle size, and distribution [1].

Step 4: Catalytic Performance Evaluation

- Reactor Setup: Testing is commonly performed in a fixed-bed quartz reactor or a dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma reactor [2]. The catalyst is packed in the reactor zone.

- Reaction Conditions: For tar reforming, a model compound like toluene is vaporized and fed into the reactor with a carrier gas (CO₂, steam, or N₂). Typical conditions include temperatures of 250-800°C and ambient pressure [2].

- Performance Metrics: The key metrics measured are:

- Tar Conversion:

X_tar (%) = [(C_tar,in - C_tar,out) / C_tar,in] × 100% - Gas Yield: The yield of H₂, CO, and CO₂ in the product gas is quantified.

- Syngas Selectivity: The selectivity towards H₂ and CO in the gaseous products is calculated.

- Tar Conversion:

Step 5: Product Analysis and Deactivation Study

- Gas Analysis: The composition of the product gas is routinely analyzed by gas chromatography (GC) or mass spectrometry (MS) [2].

- Tar Analysis: Condensable tars are captured and analyzed gravimetrically or using chromatographic techniques.

- Stability Assessment: Long-term runs (e.g., >5 hours) are conducted to monitor changes in conversion and selectivity, followed by post-reaction characterization of spent catalysts to study deactivation mechanisms like coking or sintering [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Catalyst Research and Testing

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| γ-Al₂O₃ (Alumina) | A common catalyst support material; provides high surface area and thermal stability [4] [2]. |

| Metal Precursors (e.g., Ni(NO₃)₂, Fe(NO₃)₃, RuCl₃, PdCl₂) | Sources of active metal components for catalyst synthesis via impregnation [4] [2]. |

| Reducing Agents (e.g., H₂, NaBH₄, H₂CO) | Used during catalyst activation to convert metal oxides or salts into their active metallic state [4]. |

| Tar Model Compounds (e.g., Toluene, Naphthalene) | Simpler compounds representing biomass tar components, allowing controlled studies of reforming mechanisms [2]. |

| Gasifying Agents (e.g., CO₂, Steam) | Reactive gases used in the reforming process to convert tars into syngas [1] [2]. |

| Characterization Gases (e.g., N₂ for BET) | High-purity gases used for analyzing the physical properties of the catalyst, such as surface area and porosity. |

The choice between transition metal and noble metal catalysts for biomass gasification involves a multi-faceted trade-off between activity, stability, and cost. Transition metals, particularly Ni and Fe, offer a compelling balance of high activity for tar reforming and low cost, making them strong candidates for large-scale applications, though their susceptibility to deactivation requires mitigation through alloying or process optimization [2] [3]. Noble metals excel in specific performance metrics, including superior low-temperature activity and enhanced resistance to deactivation, but their high cost may limit widespread industrial deployment [4] [5].

The ongoing research paradigm is increasingly focused on developing sophisticated hybrid and bimetallic systems that combine the advantages of both classes, such as Ru-Ni and Ni-Fe alloys, to create synergistic effects that suppress coke deposition and enhance hydrogen selectivity [1]. Furthermore, the integration of these metal-based catalysts with emerging carbon-based materials like functionalized biochars, which offer multifunctionality and potential cost benefits, represents a promising direction for next-generation, carbon-neutral biomass gasification systems [1].

In the quest for sustainable energy, biomass gasification has emerged as a pivotal technology for producing syngas—a mixture primarily of hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and methane. A significant challenge in this process is the formation of tar, a complex mixture of hydrocarbons that condenses at lower temperatures, causing blockages, corrosion, and catalyst deactivation [6]. Traditionally, metal-based catalysts, particularly Ni-based ones, have been effective in tar reforming but face issues like coking, sintering, and high cost [2]. This context has propelled the development of carbon-based catalysts, notably biochar and activated carbon, which offer a promising, sustainable, and cost-effective alternative.

Carbon-based catalysts present several inherent advantages: they are typically derived from abundant and renewable biomass waste, exhibit inherent resistance to sulfur poisoning, and can be engineered with high surface areas and tailored surface chemistry. Furthermore, their conductive properties and ability to be functionalized or doped with active metals make them highly versatile. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of biochar and activated carbon, framing their performance within the broader research context of metal-based versus carbon-based catalytic strategies for advanced biomass gasification.

Performance Comparison: Biochar vs. Activated Carbon

The selection of a catalyst involves balancing performance, economic, and environmental factors. The following tables summarize a quantitative comparison between biochar and activated carbon, drawing from life cycle assessment and performance studies.

Table 1: Environmental and Economic Performance (Production Phase)

| Parameter | Biochar | Activated Carbon | Reference Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential (GWP) | 1.53 - 2.36 kg CO₂eq/kg | 8.34 - 8.96 kg CO₂eq/kg | Gate-to-grave LCA, date palm waste source [7] |

| Cumulative Energy Demand (CED) | 20.3 MJ/kg | 119.5 MJ/kg | Gate-to-grave LCA, date palm waste source [7] |

| Production Cost | $1.06/kg | $1.34/kg | Average production cost [7] |

| Adsorption Capacity | Comparable to AC | Benchmark | Performance in water treatment/adsorption [7] |

Table 2: Catalytic Performance in Biomass Gasification and Tar Removal

| Parameter | Biochar & Modified Biochar | Activated Carbon (AC) | Reference Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tar Removal Efficiency | Up to ~91% (KOH-activated) [6] | High (specific % not provided) [6] | Catalytic gasification, model tar compounds |

| Syngas Yield Enhancement | Significant increase reported | Higher than unmodified biochar | Use as catalyst/support in gasification [6] |

| Surface Area (BET) | Improves with activation (e.g., KOH) | Generally superior to unmodified biochar | Physicochemical characterization [6] [8] |

| Active Metal Dispersion | Effective support for Fe, Ni-Fe | Effective support, but raw biomass may offer better reduction | Catalyst preparation for gasification [6] |

The data reveals a clear trend: biochar holds a significant advantage in terms of environmental footprint and cost, while possessing comparable adsorption and catalytic potential to activated carbon when properly engineered. The high CED and GWP of activated carbon are attributed to its more energy-intensive production process, often involving higher temperatures and chemical activators.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To contextualize the performance data, it is essential to understand the experimental methodologies used in preparing and evaluating these carbon catalysts.

Catalyst Preparation and Activation

1. Biochar and Activated Carbon Production:

- Pyrolysis: Biomass (e.g., sawdust, date palm waste) is pyrolyzed in an inert atmosphere at temperatures typically ranging from 400°C to 700°C to produce raw biochar [7] [6].

- Chemical Activation: To create activated carbon or activated biochar, the carbon material is impregnated with a chemical agent.

- KOH Activation: A common method involves impregnating biochar with KOH (e.g., at a 2:1 KOH-to-feedstock ratio) and heating to 800°C in an inert atmosphere [6]. The reactions produce gases (CO, CO₂) that etch pores, significantly increasing surface area.

- H₂O₂ Activation: For a milder activation, biochar can be stirred in a H₂O₂ solution (e.g., 1-10% w/v) for 24 hours at room temperature, then rinsed and dried [9].

2. Synthesis of Metal-Loaded Carbon Catalysts:

- Impregnation-Calcination: Carbon supports (raw biomass, biochar, or AC) are immersed in a solution containing metal precursors (e.g., Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O, Ni salts). The mixture is dried and then calcined at high temperatures (e.g., 300-500°C) in an inert atmosphere to decompose the salts and form metal oxide nanoparticles on the carbon surface [6] [2].

- Promoter Addition: Promoters like potassium (from K₂CO₃) can be co-impregnated with the active metals to enhance reducibility and catalytic activity, particularly in tar cracking and water-gas-shift reactions [6].

Catalytic Performance Evaluation

1. Tar Reforming Experiments:

- Setup: Experiments are conducted in a fixed-bed or fluidized-bed reactor system. A stream containing a model tar compound (e.g., toluene) is passed over the catalyst bed at controlled temperatures (e.g., 250-800°C) [6] [2].

- Plasma-Catalysis: Some advanced setups integrate a Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) non-thermal plasma reactor with the catalyst, allowing for high-efficiency tar reforming at lower temperatures (~250°C) [2].

- Analysis: The product gas is analyzed using gas chromatography (GC) to determine syngas composition (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄). Tar conversion efficiency is calculated based on the difference in tar concentration at the inlet and outlet [6] [2].

2. Adsorption Performance Evaluation:

- Batch Experiments: For water treatment applications, a known amount of adsorbent (biochar or AC) is added to a solution of a target pollutant (e.g., ciprofloxacin, methylene blue). The mixture is agitated for a set time [8].

- Analysis: The concentration remaining in the solution is measured using techniques like UV-Vis spectroscopy or Total Organic Carbon (TOC) analysis. Adsorption isotherms (e.g., Langmuir, Freundlich) and kinetic models are then applied to the data to quantify performance and understand mechanisms [8].

Emerging Architectures and Functionalization

The frontier of carbon catalyst research involves engineering their architecture and chemistry to surpass traditional performance limits.

Metal-Carbon Hybrids: A primary strategy is embedding transition metals like Fe and Ni into the carbon matrix. Bimetallic Ni-Fe catalysts on biochar supports have demonstrated exceptional performance, where Fe promotes the reduction of Ni and provides lattice oxygen to gasify carbon deposits, mitigating deactivation [6] [2]. The Ni/Fe molar ratio is a critical design parameter, with Ni₃-Fe₁/Al₂O³ showing high syngas selectivity and carbon resistance [2].

Chemical Functionalization: Activating biochar with agents like KOH or H₂O₂ creates oxygen-containing functional groups (e.g., carboxyl, hydroxyl) on its surface. These groups enhance hydrophilicity and provide anchoring sites for metals, improving dispersion and catalytic activity [8] [9]. Studies show that H₂O₂-activated biochar can achieve contaminant rejection rates as high as 92.4% when embedded in membranes [9].

Morphological Tuning: Controlling pyrolysis and activation conditions (temperature, heating rate) allows for tuning of porosity and surface area. Fast pyrolysis and chemical activation are preferred for developing high surface area and micro/mesopores crucial for reactant access and mass transfer [6] [10].

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected strategies for developing advanced carbon-based catalysts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

This table lists essential materials and their functions for researchers working in carbon-based catalysis for biomass gasification.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Biomass Precursors | Feedstock for producing biochar and activated carbon, determining initial porosity and ash content. | Woody sawdust, date palm waste, oak shells, rice husk [6] [8] [10]. |

| Chemical Activators | Agents used to etch and develop porosity in carbon materials, increasing surface area and functionality. | KOH, K₂CO₃, H₃PO₄, H₂O₂, CO₂ (physical activation) [6] [8] [9]. |

| Metal Precursors | Sources of active catalytic metals for impregnation onto carbon supports to enhance tar cracking. | Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O, Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O [6] [2]. |

| Promoter Precursors | Additives that improve metal dispersion, reducibility, or specific catalytic functions (e.g., WGS reaction). | K₂CO₃ [6]. |

| Model Tar Compounds | Simplified surrogates for complex biomass tar, enabling controlled and reproducible catalytic testing. | Toluene, benzene, naphthalene [2]. |

| Polymer Binders/Supports | Used to create composite materials, such as catalytic membranes for integrated reaction-separation processes. | Polysulfone (PSf), N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) solvent [9]. |

The comparative analysis underscores that the choice between biochar and activated carbon is not a simple declaration of a superior material, but a strategic decision based on application priorities. Biochar stands out as the more sustainable and economically viable option, with a significantly lower environmental footprint and cost. Its performance is comparable to activated carbon, especially when modified through activation or metal functionalization. Activated carbon, while more energy-intensive to produce, often provides a benchmark in porosity and, in some cases, catalytic activity.

The future of carbon-based catalysts lies in the design of emerging hybrid architectures. The integration of inexpensive, active metals like Fe and Ni, combined with precise control over porosity and surface chemistry, creates synergistic effects that can outperform traditional catalysts. These advanced carbon materials bridge the gap between the sustainability of pure carbon and the high activity of metal-based systems, offering a compelling pathway for making biomass gasification a more efficient and commercially viable technology for renewable energy and chemicals production.

Gasification stands as a pivotal thermochemical technology for converting carbonaceous feedstocks like biomass and municipal solid waste into syngas, a valuable mixture of hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and other gases [11]. However, the formation of tar—a complex mixture of condensable, high molecular weight hydrocarbons—poses a significant challenge by degrading downstream equipment and poisoning catalytic processes [11]. Catalytic interventions are therefore indispensable for efficient gasification, primarily focusing on three core reactions: tar cracking, tar reforming, and the water-gas shift reaction [1] [12].

This guide objectively compares the performance of metal-based and carbon-based catalysts in driving these critical reactions, framing the analysis within ongoing research debates about catalyst selection for sustainable biomass gasification. Metal-based catalysts, particularly those incorporating nickel, are renowned for their high activity, while carbon-based catalysts, such as engineered biochars, offer advantages in cost, resistance to poisoning, and multifunctionality [1] [12]. The following sections provide a detailed comparison of their mechanistic actions, summarized experimental data, and essential research protocols.

Catalytic Mechanisms and Pathways

Metal-Based Catalysts

Metal-based catalysts, especially those incorporating transition metals like nickel, operate primarily through heterogeneous catalysis on their active metallic surfaces [1]. The process for tar reforming typically involves several key stages, as illustrated in the catalytic cycle below.

Tar Reforming Cycle on a Ni-based Catalyst

Figure 1: The catalytic cycle of tar steam reforming on a Ni-based catalyst surface.

The mechanism begins with the adsorption of tar molecules and steam onto the active metal sites (e.g., Ni). The C-C bonds in the tar are cleaved on the metal surface, while steam dissociates into hydroxyl species and hydrogen [1]. Subsequent surface reactions involve the reformed carbon species reacting with oxygen from hydroxyl groups to produce CO, while hydrogen atoms recombine into H2. Finally, the product molecules (CO and H2) desorb from the catalyst surface, regenerating the active sites for the next cycle [13]. The water-gas shift reaction (CO + H2O CO2 + H2) often proceeds in parallel on the same catalyst, further adjusting the syngas composition [14] [12].

Carbon-Based Catalysts

Carbon-based catalysts (CBCs), such as activated biochar, function through a combination of physical adsorption and surface-mediated reactions. Their functionality is heavily dependent on their engineered structure.

Dual-Function Mechanism of Activated Biochar

Figure 2: The multifunctional mechanism of tar removal using an activated biochar catalyst.

The process involves two synergistic mechanisms [1]. First, porous adsorption captures heavy tar molecules (e.g., fluorene) within the hierarchical pore structure of the biochar. Second, catalytic reforming occurs where inherent metal species (e.g., Ca, Al) or other active sites on the biochar surface catalyze the reforming of lighter tar compounds (e.g., phenol) into syngas [1]. This dual functionality allows CBCs to efficiently process a wide range of tar compounds.

Comparative Performance Data

Tar Conversion and Hydrogen Yield

The performance of metal-based and carbon-based catalysts is quantified through key metrics such as tar conversion efficiency and hydrogen yield. The table below summarizes experimental data from recent studies.

Table 1: Comparative performance of metal-based and carbon-based catalysts in gasification reactions.

| Catalyst Type | Specific Catalyst | Experimental Conditions | Tar Conversion (%) | H₂ Yield / Concentration | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal-Based | Novel Ni-based (C&CS #1050 B) | 700-800 °C, GHSV: 6000 h⁻¹, 50-100 ppm H₂S | ~100% (at 700°C with 50 ppm H₂S) | Not Specified | Superior performance vs. commercial catalyst; high H₂S tolerance. | [15] |

| Metal-Based | Ni/Active Carbon | 800 °C, Steam/Biomass: 4 | Not Specified | 64.02 vol% | High Ni content (15%) crucial for maximizing H₂ yield. | [16] |

| Carbon-Based | Activated Biochar (A-Biochar) | 800 °C, coupled with SiC membrane | 96.4% | Not Specified | Hierarchical pores adsorbed heavy tar; inherent Ca/Al species reformed light tar. | [1] |

| Metal-Based | Red Mud (RM) | Not Specified | Not Specified | 50-55 vol% | Effective low-cost catalyst due to Fe₂O₃ and Al₂O₃ composition. | [16] |

| Homogeneous | K₂CO₃ | 600 °C, Batch Reactor | Not Specified | 28 mmol/g (from glucose) | Enhances water-gas shift reaction, limiting char formation. | [12] |

Catalyst Durability and Deactivation

Long-term stability is a critical differentiator between catalyst types.

Table 2: Comparison of catalyst deactivation mechanisms and regeneration strategies.

| Aspect | Metal-Based Catalysts | Carbon-Based Catalysts (CBCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Deactivation Mechanisms | Coke (carbon) deposition, Sintering (loss of active surface), Poisoning (e.g., by sulfur) [1]. | Pore blockage by coke/ash, Attrition, Oxidation [1]. |

| Coke Formation Example | Conventional heating can lead to stable graphitic coke [1]. | Coke formation is suppressed in systems like microwave-assisted cracking [1]. |

| Regeneration Strategies | Controlled combustion to remove coke [1]. | Controlled combustion, Steam activation [1]. |

| Resistance to Poisons | Susceptible to sulfur poisoning (e.g., H₂S) [1]. | Often exhibit superior resistance to sulfur poisons [1]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Catalyst Testing and Evaluation

Standardized experimental protocols are essential for comparing catalyst performance. A common setup involves a laboratory-scale packed bed reactor.

Typical Workflow for Catalytic Tar Reforming Experiments

Figure 3: Generalized experimental workflow for testing gasification catalysts.

Key steps include:

- Catalyst Preparation: Metal-based catalysts are often synthesized via impregnation, where a support material is infused with an aqueous solution of a metal salt (e.g., PtCl₄, Ni salts), followed by drying and reduction in a H₂ atmosphere at high temperatures (e.g., 1073 K) [14] [16]. Carbon-based catalysts may be derived from biomass precursors through pyrolysis and subsequent physical or chemical activation to develop porosity and surface functional groups [1].

- Reactor Setup: Experiments are frequently conducted in tubular fixed-bed quartz reactors [14] [15]. The catalyst is typically reduced in-situ under a H₂ flow before introducing reactants.

- Simulated Syngas Feed: To ensure reproducibility, model tar compounds like naphthalene and toluene are dissolved and vaporized into a carrier gas (e.g., N₂). Thiophene can be added as a source of H₂S to study poisoning [15]. Steam is co-fed as a reforming agent.

- Product Analysis: The composition of the outlet gas (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄) is analyzed using gas chromatography (GC). Tar conversion is calculated by quantifying the tar content before and after the catalytic reactor using standardized tar sampling protocols [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential materials and reagents for catalytic gasification research.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Nickel Salts (e.g., Ni(NO₃)₂) | Precursor for active metal in catalyst synthesis. | Impregnation of alumina or biochar supports to create Ni-based catalysts [16]. |

| Biochar / Activated Carbon | Catalyst support or catalyst itself. | Used as a low-cost support for Ni or as a standalone catalyst with inherent activity [1] [16]. |

| Alumina (Al₂O₃) | Stable, high-surface-area catalyst support. | A common support for Ni and other transition metals due to its stability and textural properties [16]. |

| Naphthalene / Toluene | Model tar compounds. | Used in simulated syngas feeds to study catalytic tar reforming efficiency under controlled conditions [15]. |

| Thiophene (C₄H₄S) | Source of H₂S for poisoning studies. | Added to the reactant stream to investigate catalyst resistance to sulfur poisoning [15]. |

| Calcium Oxide (CaO) | CO₂ adsorbent and catalyst. | Used in sorption-enhanced gasification to shift reaction equilibria and increase H₂ yield [16]. |

| Red Mud (RM) | Low-cost iron and aluminum-rich catalyst. | A waste-derived catalyst from aluminum processing used for tar reduction [16]. |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that the choice between metal-based and carbon-based catalysts is not a simple binary decision. Each class offers distinct advantages: metal-based catalysts, particularly advanced Ni formulations and bimetallics, provide exceptional activity and tar conversion efficiency [15] [1]. In contrast, carbon-based catalysts, such as engineered biochars, offer a compelling combination of multifunctionality, resistance to poisoning, and alignment with circular economy principles, often at a lower cost [1].

The optimal catalyst selection depends heavily on the specific gasification process conditions, feedstock composition, and economic constraints. Future research is trending towards hybrid and advanced material designs, such as nanostructuring, single-atom catalysts on carbon supports, and the use of AI-driven computational models to predict optimal catalyst formulations [1]. These innovations aim to bridge the performance gap between the two catalyst classes, ultimately leading to more robust, efficient, and economically viable biomass gasification systems.

In the quest for sustainable and carbon-neutral energy systems, biomass gasification stands out as a pivotal technology for converting biomass into syngas, a key precursor for fuels and chemicals. Within this field, the choice of catalyst is paramount, framing a central thesis of metal-based versus carbon-based catalysts. While traditional metal-based catalysts, such as nickel, are renowned for their high activity, particularly in C-C bond rupture and tar reforming, they often face challenges related to cost, sintering, coking, and deactivation [1] [16]. This comparison guide objectively explores the unique multifunctionality of carbon-based catalysts (CBCs), which present a compelling alternative by combining intrinsic catalytic activity with in-situ CO₂ adsorption capabilities. This dual functionality positions CBCs as robust, cost-effective, and environmentally benign candidates for next-generation gasification systems, aligning with the principles of a circular carbon economy [1] [17].

Comparative Performance Analysis: Carbon-Based vs. Metal-Based Catalysts

The performance of catalysts in biomass gasification is typically evaluated based on their tar conversion efficiency, hydrogen yield, resistance to deactivation, and additional functionalities such as CO₂ adsorption. The table below provides a structured comparison of carbon-based catalysts against common metal-based alternatives, synthesizing data from recent experimental studies.

Table 1: Performance comparison of carbon-based and metal-based catalysts in biomass gasification

| Catalyst Type | Specific Example | Tar Conversion Efficiency | H₂ Yield / Concentration | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon-Based Catalysts | Activated Biochar (A-biochar) | 96.4% [1] | – | Dual functionality (tar cracking & CO₂ adsorption), waste-derived, cost-effective, superior thermal & poison resistance [1] | Trade-offs between activity, adsorption capacity, and mechanical strength [1] |

| Ni/Active Carbon (15% Ni) | – | 64.02 vol% [16] | High H₂ production, activated carbon support enhances total gas yield [16] | Catalyst cost, potential Ni sintering [1] | |

| Metal-Based Catalysts | Ni-based Catalysts | >90% [1] | 60-70 vol% [16] | High activity for C-C bond rupture, widely used, effective for tar reduction [16] | Substantial cost, susceptibility to coking and sintering, deactivation [1] [16] |

| Red Mud (RM) | Effective in reduction [16] | 50-55 vol% [16] | Low-cost byproduct, composition of Fe₂O₃ and Al₂O₃ [16] | Limited number of studies, lower H₂ yield compared to Ni catalysts [16] | |

| CaO | – | Improved composition [16] | Excellent CO₂ adsorbent (shifts equilibrium for H₂ production) [16] | – |

The data indicates that CBCs, particularly activated biochar, can achieve performance on par with or even superior to traditional metal catalysts in key areas like tar conversion. Their defining advantage, however, lies in their multifunctionality. Unlike metal-based catalysts that primarily drive tar reforming, CBCs can simultaneously catalyze reactions like tar cracking and the water-gas shift while also adsorbing CO₂ in situ. This integrated approach simplifies process design and enhances overall system efficiency [1].

The Dual Functionality of Carbon-Based Catalysts: Mechanisms and Workflow

The superior performance of multifunctional carbon-based catalysts stems from their synergistic structural and chemical properties. The following diagram illustrates the concurrent processes and mechanisms within a gasification system employing a CBC.

Diagram 1: Multifunctional mechanisms of carbon-based catalysts in gasification.

Intrinsic Catalytic Activity

The catalytic activity of CBCs for tar cracking and reforming is a result of two primary factors:

- Hierarchical Pore Structure: Biomass-derived carbons possess a tunable pore structure, comprising micropores (<2 nm), mesopores (2-50 nm), and macropores (>50 nm) [17]. This hierarchy is critical, as macropores facilitate mass transfer, while micropores and mesopores provide a high surface area for reactions. For instance, hierarchical pores in activated biochar can physically adsorb heavy tars like fluorene [1].

- Active Sites: The inherent presence of alkali or alkaline earth metal species (e.g., K, Ca) and other inorganic impurities in the biochar matrix provides catalytic active sites [16] [17]. These sites, such as Ca/Al species, are highly effective in catalytically reforming light tars like phenol [1]. Furthermore, the carbon matrix can be functionalized or doped with heteroatoms (e.g., O, N) or transition metals (e.g., Ni) to significantly enhance active site density and stability for specific reactions [1].

In-Situ CO2 Adsorption

A unique property of CBCs is their ability to adsorb CO₂ generated during the gasification process. This occurs through two main mechanisms:

- Physicochemical Adsorption: The high surface area and porous structure enable physical adsorption of CO₂ molecules [1]. Additionally, surface oxygenated functional groups (e.g., carboxyl, carbonyl) can establish specific interactions with CO₂, facilitating chemisorption [1].

- Oxygen Vacancies and Defect Sites: In metal-oxide-functionalized carbons, surface defects and oxygen vacancies play a crucial role in CO₂ activation. These vacancies enrich transferable electrons and act as adsorption sites, promoting the transformation of the stable CO₂ molecule [18].

This in-situ CO₂ capture, particularly in processes like sorption-enhanced gasification (SEG), shifts the reaction equilibrium according to Le Chatelier's principle, leading to a significant increase in hydrogen yield and purity while simultaneously concentrating CO₂ for capture or utilization [1] [16].

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Carbon Catalysts

To objectively compare catalyst performance, standardized experimental protocols are essential. Below are detailed methodologies for synthesizing and testing carbon-based catalysts, as cited in recent literature.

Catalyst Synthesis and Characterization

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Activated Biochar (A-Biochar) for Integrated Tar and PM Removal This protocol is adapted from the work of Ding et al., which demonstrated concurrent tar reforming and particulate matter (PM) filtration [1].

- Carbonization: Subject a selected biomass feedstock (e.g., sawdust, pruning remains) to pyrolysis under an inert atmosphere (e.g., N₂) at a temperature typically between 500-800°C to produce raw biochar.

- Activation: Activate the raw biochar using a physical or chemical agent. Common activating agents include CO₂, steam, or bases like KOH. This step develops porosity and increases the specific surface area.

- Characterization:

- Textural Properties: Use N₂ adsorption-desorption at -196°C to determine the specific surface area (BET method) and pore size distribution. Complementary CO₂ adsorption at 0°C can characterize the smallest micropores [17].

- Surface Chemistry: Analyze surface functional groups using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR).

- Morphology and Composition: Examine the catalyst's morphology using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and determine elemental composition.

Protocol 2: Preparation of Ni/Active Carbon Catalyst This protocol is based on studies achieving high hydrogen production with Ni-supported on activated carbon [16].

- Support Preparation: Obtain or synthesize activated carbon with a high surface area, as detailed in Protocol 1.

- Metal Impregnation: Impregnate the activated carbon support with an aqueous solution of nickel nitrate (Ni(NO₃)₂) to achieve the desired metal loading (e.g., 15 wt% Ni).

- Drying and Calcination: Dry the impregnated catalyst followed by calcination in air at a specified temperature to convert the nickel salt to its oxide form.

- Reduction (Optional): Reduce the calcined catalyst in a H₂ stream at high temperature (e.g., 500-700°C) to form metallic Ni nanoparticles, which are the active sites for C-C bond rupture [16].

Catalytic Performance Testing

Protocol 3: Bench-Scale Gasification and Tar Conversion Test

- Reactor Setup: Conduct experiments in a fixed-bed or fluidized-bed reactor system. The reactor should be equipped with a temperature-controlled furnace, a biomass feeding unit, and a gasifying agent (steam, air) supply.

- Experimental Run: Load a specific amount of catalyst (e.g., 75 g of biomass mixture [16]) into the reactor. Initiate gasification at the target temperature (e.g., 800°C [1] [16]) with a controlled steam-to-biomass ratio (e.g., 4 [16]).

- Syngas Analysis: Analyze the product gas composition (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄) in real-time using online gas chromatography (GC).

- Tar Measurement: Collect tar samples from the syngas stream using a protocol such as the "Tar Protocol" [16]. Quantify tar species gravimetrically or using GC-MS.

- Performance Calculation:

- Tar Conversion Efficiency: Calculate as

(1 - (Tar output with catalyst / Tar output without catalyst)) * 100%. - H₂ Yield/Concentration: Determine from the GC data, reported as vol% in the product gas.

- Tar Conversion Efficiency: Calculate as

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for research and development in carbon-based catalysts for biomass gasification.

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for carbon catalyst development

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Characteristics & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Lignocellulosic Biomass | Feedstock for producing sustainable biochar and activated carbon [17]. | Composition (lignin, cellulose, hemicellulose) influences biochar yield and properties. Prefer terrestrial over aquatic materials [17]. |

| Activating Agents (KOH, CO₂) | Used in the chemical or physical activation of biochar to develop porosity [17]. | KOH creates uniform micropores; CO₂ activation is less corrosive. Choice affects final surface area and pore size distribution. |

| Metal Precursors (e.g., Ni(NO₃)₂) | For synthesizing metal-doped carbon catalysts to enhance tar reforming activity [1] [16]. | High-purity salts ensure consistent metal loading. Nitrates are common due to good solubility and decomposition properties. |

| Silicon Carbide (SiC) Membrane | Used in integrated reactor designs for simultaneous particulate matter (PM) removal, preventing catalyst fouling [1]. | High thermal stability and defined pore size (e.g., 2.6 μm) for efficient PM capture (>95.9%) at high temperatures [1]. |

| Model Tar Compounds | Used in controlled laboratory experiments to standardize the evaluation of catalytic tar cracking performance. | Phenol and fluorene are representative of light and heavy tars, respectively [1]. |

This comparison guide demonstrates that carbon-based catalysts are not merely substitutes for metal-based catalysts but represent a paradigm shift in catalyst design for biomass gasification. Their unique multifunctionality—integrating high catalytic activity for tar reduction with in-situ CO₂ adsorption—offers a pathway to more efficient, cost-effective, and environmentally sustainable gasification processes. While metal-based catalysts like Ni continue to be highly active, their limitations in cost and deactivation highlight the compelling advantages of CBCs. Future research, accelerated by computational tools like density functional theory (DFT) and machine learning, should focus on optimizing the trade-offs between catalytic activity, CO₂ adsorption capacity, and long-term stability under cyclic operations to fully realize the potential of carbon catalysts in enabling a circular carbon economy [1].

Strong Metal-Support Interactions (SMSI) and Alloying Effects in Advanced Catalytic Design

The pursuit of efficient and sustainable chemical processes, particularly in the realm of biomass gasification, hinges on advanced catalyst design. Two dominant paradigms have emerged: metal-based catalysts and carbon-based catalysts. Within metal-based systems, strategic engineering of Strong Metal-Support Interactions (SMSI) and deliberate alloying effects have proven to be powerful tools for enhancing catalytic performance, stability, and selectivity. SMSI describes a phenomenon where a reducible oxide support migrates onto supported metal nanoparticles under specific conditions, forming an encapsulating layer that modifies the electronic and geometric structure of the active metal sites [19]. This interaction can significantly alter adsorption strengths and reaction pathways. Concurrently, alloying—combining two or more metals—allows for the fine-tuning of electronic structures and the creation of unique active sites, with recent advances extending into high-entropy alloys (HEAs) that offer vast compositional space and synergistic effects [19]. This guide objectively compares the performance of catalysts leveraging these advanced design principles against more conventional alternatives, providing a foundational understanding for researchers and scientists developing next-generation solutions for biomass conversion and other critical processes.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Key Concepts

Strong Metal-Support Interactions (SMSI)

The classic SMSI effect is characterized by the encapsulation of metal nanoparticles by a partially reduced oxide support layer following high-temperature reductive treatment [20] [19]. This overlay induces both geometric and electronic modifications to the catalyst. Geometrically, the encapsulating layer can physically isolate active sites, altering selectivity by controlling access to reactants. Electronically, charge redistribution occurs at the metal-support interface, modulating the electron density of the metal sites and thereby influencing their binding strength with reaction intermediates [19]. Originally observed for Group VIII metals on reducible oxides like TiO2, Co3O4, and CeO2, the boundaries of SMSI have been expanded through innovative synthesis routes. These include treatments under oxidative atmospheres, wet chemistry approaches in aqueous solutions, and the use of strongly adsorbed molecules as mediators, making the effect accessible to a wider range of metals, including Au, Pt, Pd, and Rh [20].

A significant advancement is the concept of Strong Metal-Support Interaction via a Reverse Route (SMSIR). Unlike the conventional approach that starts from deposited metal nanoparticles and ends with encapsulation, SMSIR begins with a pre-formed core-shell structure (the final state of conventional SMSI) and applies a reductive treatment to create a porous yolk-shell structure. This "reverse" process results in a controlled, partial exposure of metal sites, offering an optimal balance between active site accessibility and nanoparticle stabilization [20].

Alloying and High-Entropy Alloy Effects

Alloying involves creating materials with two or more metallic elements. In catalysis, it is primarily used to tailor the electronic structure of active sites. Introducing a second metal can shift the d-band center of the primary active metal, thereby weakening or strengthening the adsorption of key intermediates and lowering energy barriers for catalytic reactions [21]. This electronic modulation is a key reason why Pt-based alloys often outperform pure Pt in reactions like the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) [21].

HEAs represent a frontier in alloy catalysis. Composed of five or more elements in near-equiatomic proportions, they offer an immense compositional space for discovering new catalysts with unique properties [19]. Their complex compositions lead to pronounced synergistic effects and a diverse array of active sites, enabling fine control over reaction pathways. A critical challenge, however, is synthesizing ultrasmall HEA nanoparticles (<5 nm) that are resistant to aggregation and phase segregation under high-temperature conditions. Recent work demonstrates that leveraging the SMSI effect is an effective strategy to stabilize these ultrasmall HEAs, preventing Ostwald ripening and maintaining compositional homogeneity [19].

Comparative Performance Analysis of Catalytic Systems

The following tables provide a quantitative comparison of catalyst performance across different reactions, highlighting the impact of SMSI and alloying.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Metal-Based Catalysts in Hydrogenation and Oxidation Reactions

| Catalyst | Reaction | Key Performance Metrics | Comparison / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pd–Fe₃O₄–H (SMSIR) [20] | Acetylene Semi-Hydrogenation | 100% Conversion, 85.1% Selectivity to Ethylene @ 80°C | Superior selectivity due to SMSIR favoring surface-H over hydride formation. |

| Ultrasmall HEA/TiO₂ (SMSI) [19] | Cinnamaldehyde Hydrogenation | High Conversion & Tunable Selectivity | SMSI layer stabilizes sub-3.7 nm particles and fine-tunes interfacial electronic structure. |

| Pt₁/FeOₓ (Single-Atom) [22] | CO Oxidation | Higher activity than Au Nanoparticle catalysts | Demonstrated the potential of single-atom catalysis with maximum atom utilization. |

| Ir₁/m-WO₃ (Single-Atom) [22] | CO-SCR (NO Reduction) | 73% NO Conversion @ 350°C; 100% N₂ Selectivity | Isolated active sites provide excellent selectivity for target products. |

Table 2: Performance of Catalysts in Biomass Gasification and Syngas Production

| Catalyst | Process / Reaction | Key Performance Metrics | Comparison / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ni/Active Carbon (15% Ni) [16] | Biomass Steam Gasification | 64.02 vol% H₂ Production @ 800°C, S/B=4 | High Ni content increases H₂ and gas yields; effective for tar reduction. |

| Red Mud (RM) Catalyst [16] | Biomass Gasification | 50-55 vol% H₂ Production | Effective low-cost catalyst due to Fe₂O₃ and Al₂O₃ composition. |

| Activated Biochar (A-Biochar) + SiC Membrane [1] | Syngas Purification (Tar & PM Removal) | 96.4% Tar Conversion, >95.9% PM Removal | Multifunctional carbon-based system for integrated syngas cleaning. |

| Ni–Ce@SiC (Microwave) [1] | Tar Reforming | >90% Tar Conversion, >30% Coke Reduction | Microwave heating suppresses coke deposition vs. conventional heating. |

Table 3: Advantages and Limitations of Catalyst Design Strategies

| Design Strategy | Key Advantages | Primary Challenges | Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMSI | Enhances thermal stability; suppresses sintering & dissolution; modulates selectivity [20] [19]. | Can over-encapsulate and block active sites; restricted to specific metal-support pairs [20]. | Ideal for high-temperature reactions where metal stability is critical. |

| Alloying & HEA | Vast tunability of electronic structure; synergistic effects; unique active sites [19] [21]. | Thermodynamic instability; aggregation & phase segregation (Ostwald ripening) [19]. | Optimal for reactions requiring precise adsorption energy tuning. |

| Carbon-Based Catalysts (e.g., Biochar) | Multifunctionality (catalyst & adsorbent); derived from waste resources; resistance to sulfur poisoning [1]. | Can suffer from pore blockage by coke/ash; lower activity for some reforming reactions [1]. | Excellent for integrated CO₂ capture and in syngas purification processes. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Inducing SMSI via the Reverse Route (SMSIR)

The SMSIR strategy represents a controlled method for constructing optimized metal-support interfaces [20].

- Synthesis of Core-Shell Nanoparticles: Begin with the synthesis of monodisperse Pd nanoparticles (∼5.5 nm) via the reduction of palladium(II) acetylacetonate (Pd(acac)₂) in oleylamine. Use these as seeds for a secondary growth step. Introduce iron(III) acetylacetonate to nucleate and grow an amorphous iron oxide (FeOₓ) shell around the Pd cores, resulting in core-shell Pd–FeOₓ nanoparticles.

- SMSIR Construction: Subject the pristine core-shell nanoparticles to a reductive annealing process. A typical protocol involves treating the material at 300°C under a gas mixture of 4% H₂ in Ar. This treatment triggers the crystallization of the shell into Fe₃O₄ and induces the formation of a porous yolk-shell structure (Pd–Fe₃O₄–H), characterized by abundant micropores (average ~0.73 nm) in the shell.

- Characterization: Use Aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM and EELS mapping to confirm the transformation from a core-shell to a porous yolk-shell morphology. XRD analysis will show the emergence of crystalline γ-Fe₃O₄ phases and intensified Pd (111) peaks after reductive treatment.

Synthesizing Ultrasmall High-Entropy Alloy Nanoparticles via SMSI

This quenching-based method stabilizes ultrasmall HEAs by leveraging SMSI [19].

- Support Pretreatment: Pre-calcine the anatase TiO₂ support in air. This step generates lattice defects and a controlled concentration of oxygen vacancies, which serve as anchoring sites for metal precursors.

- Quenching and Impregnation: Prepare an aqueous solution containing equimolar (e.g., 0.5 mmol each) salts of the target metals (e.g., Pt, Ni, Co, Cu, Fe) along with citric acid as a complexing agent. Rapidly quench the high-temperature TiO₂ support into this metal salt solution. The violent release of steam promotes the immediate and uniform adsorption of metal complexes onto the defect-rich TiO₂ surface.

- Reductive Annealing: Reduce the metal precursors under a H₂ atmosphere at high temperature (e.g., 500–700°C). This step forms the ultrasmall HEA nanoparticles and simultaneously induces the SMSI effect, resulting in the formation of a thin TiOₓ encapsulation layer that stabilizes the nanoparticles against aggregation.

- Characterization: Employ TEM to verify particle size (<3.7 nm) and dispersion. EDS and ICP-MS are used to confirm the homogeneous elemental distribution and composition of the HEA. XPS can be used to investigate the electronic interactions between the HEA and the support and the content of oxygen vacancies.

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

SMSI Engineering Pathways

Table 4: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in Catalyst Synthesis/Reaction | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Palladium(II) acetylacetonate (Pd(acac)₂) | Metal precursor for synthesizing well-defined seed nanoparticles. | Synthesis of Pd seed NPs for core-shell structures [20]. |

| Iron(III) acetylacetonate (Fe(acac)₃) | Precursor for forming the oxide shell in core-shell nanoparticles. | Formation of FeOₓ shell in Pd–FeOₓ core-shell NPs [20]. |

| Anatase TiO₂ Nanoparticles | A common reducible oxide support for inducing SMSI effects. | Support for stabilizing ultrasmall HEA nanoparticles [19]. |

| Citric Acid | Serves as a complexing agent in precursor solutions to promote uniform metal dispersion. | Used in quench synthesis of HEA catalysts to prevent segregation [19]. |

| Oleylamine (OAM) | Acts as both a solvent and a stabilizing ligand in colloidal synthesis of nanoparticles. | Synthesis of monodisperse Pd NPs [20]. |

| Red Mud (RM) | Low-cost, waste-derived catalyst containing catalytic Fe₂O₃ and Al₂O₃. | Catalyst for tar reduction and H₂ production in biomass gasification [16]. |

The strategic application of Strong Metal-Support Interactions and alloying effects provides a powerful framework for advancing catalytic design, particularly within the context of metal-based catalysts for processes like biomass gasification. The comparative data and protocols presented in this guide demonstrate that SMSI engineering can drastically improve catalyst stability and selectivity, while alloying—especially in the form of high-entropy alloys—offers unparalleled tunability of active sites. When compared to carbon-based catalysts, which excel in multifunctionality and cost-effectiveness for specific tasks like syngas purification, these advanced metal-based systems show superior performance in demanding catalytic transformations requiring high activity and precise control. Future research will likely focus on broadening the scope of SMSI to non-classical metal-support pairs, improving the synthetic control over HEA composition and size, and integrating these design principles with emerging carbon-based materials to create next-generation hybrid catalysts for a sustainable energy future.

Catalyst Applications and Process Integration: From Laboratory to System Design

Gasification represents a cornerstone thermochemical process for converting diverse biomass and waste feedstocks into syngas, a valuable mixture of hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and light hydrocarbons [23] [24]. The efficiency and output of this process are profoundly influenced by the gasification technology employed and the catalysts integrated within the system. Catalysts are pivotal for enhancing reaction rates, improving syngas quality and yield, and mitigating operational challenges such as tar formation and catalyst deactivation [25] [2]. Within the context of biomass gasification research, a central thesis involves the comparative analysis of metal-based versus carbon-based catalysts. Metal-based catalysts, particularly Ni-Fe bimetallic systems, are renowned for their high catalytic activity and effectiveness in tar reforming [2]. Carbon-based catalysts, such as biochar, offer advantages of low cost and high resistance to contaminants [25].

This guide provides an objective comparison of three advanced gasification technologies: Fluidized Bed, Supercritical Water (SCWG), and Plasma Systems. It synthesizes experimental data on catalytic performance, summarizes methodologies from key studies, and outlines essential research tools, offering a structured resource for researchers and scientists in the field.

The selection of gasification technology significantly impacts process conditions, syngas composition, and optimal catalyst choice. Fluidized bed gasifiers are characterized by excellent mixing, uniform temperature distribution, and flexibility in feedstock, typically operating between 800–1000 °C [23] [24]. Supercritical Water Gasification (SCWG) utilizes water above its critical point (374 °C, 22.1 MPa) as the reaction medium, which is particularly advantageous for processing high-moisture feedstocks like sewage sludge without an energy-intensive drying step [26] [27] [28]. The unique properties of SCW, including low dielectric constant and high diffusivity, facilitate the efficient dissolution and gasification of organic compounds into a hydrogen-rich syngas [27] [29]. Plasma gasification employs a high-temperature plasma arc (often exceeding 3000 °C) to decompose organic material completely and inertize inorganic components into a vitrified slag. This technology is highly effective for treating refractory wastes and achieving high carbon conversion rates [23] [25].

Table 1: Overview and Comparative Performance of Gasification Technologies.

| Technology | Typical Operating Conditions | Syngas Characteristics | Advantages | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluidized Bed | 800–1000 °C; Atmospheric to elevated pressure [23] [24] | H₂: ~20-40%; CO: ~20-40%; LHV: 4-18 MJ/Nm³ [23] | Good temperature uniformity, feedstock flexibility, high efficiency [24] | Tar management, bed agglomeration, particulate carryover [24] |

| Supercritical Water (SCWG) | 374-700 °C; 22-30 MPa [27] [28] [29] | H₂-rich (up to 60% or more); CO variable [26] [27] | Direct wet feed processing, high H₂ yield, compact reactors [28] [29] | Salt precipitation/clogging, corrosion, high-pressure operation [29] |

| Plasma | 500-3000+ °C; Atmospheric pressure [25] | High H₂ and CO; very low tar [25] | Very high conversion, handles diverse wastes, vitrified slag [25] | High electricity consumption, reactor durability, capital cost [25] |

Catalytic Performance: Metal-Based vs. Carbon-Based

Catalysts are essential for optimizing gasification, with metal-based and carbon-based catalysts representing two major categories. The following table summarizes key experimental findings for different catalyst types within each gasification technology.

Table 2: Experimental Catalytic Performance in Different Gasification Systems.

| Gasification System | Catalyst Type & Example | Experimental Conditions | Key Performance Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluidized Bed | Metal-based (Ni-Fe/Al₂O₃) | ~800-900°C; Steam or CO₂ as agent [2] | High tar conversion (>90%); Enhanced syngas yield and H₂ selectivity; Improved carbon resistance vs. Ni-only [2] | [2] |

| Supercritical Water (SCWG) | Metal-based (K₂CO₃) | ~500-600°C; ~25 MPa [27] | Increased H₂ yield and gasification efficiency; Catalyzes water-gas shift reaction [27] | [27] |

| Supercritical Water (SCWG) | Carbon-based (Biochar) | ~374-700°C; ~22-30 MPa [29] | In-situ tar cracking; Provides active sites for reforming; Low-cost and resistant to poisoning [29] | [29] |

| Plasma | Metal-based (Ni-Fe/Al₂O₃) | ~500-800°C; Non-thermal plasma [25] [2] | Synergy between plasma and catalyst; High tar conversion (~90%) at lower temperatures; Reduced coke formation [25] [2] | [25] [2] |

| Plasma | Carbon-based (Char) | High temp. (>1000°C); Plasma zone [25] | Acts as catalyst and reactant; Contributes to CO production via Boudouard reaction [25] | [25] |

Experimental Protocols for Catalytic Gasification

Protocol for Plasma-Catalytic Reforming of Tar using Ni-Fe/Al₂O₃

This protocol details the experimental method for non-thermal plasma-catalytic CO₂ reforming of toluene, a model tar compound, as described in the search results [2].

Catalyst Synthesis (Impregnation Method):

- Support Preparation: Use γ-Al₂O₃ as the catalyst support. Pre-treat it by calcining at 500°C for 4 hours to remove impurities and stabilize the surface.

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve appropriate amounts of nickel nitrate (Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) and iron nitrate (Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O) in deionized water to achieve the desired Ni/Fe molar ratios (e.g., 3:1, 2:1, 1:1).

- Impregnation: Slowly add the γ-Al₂O₃ support to the aqueous nitrate solution under continuous stirring. Allow the mixture to age for 12-24 hours at room temperature.

- Drying & Calcination: Recover the solid catalyst, dry it at 105°C for 12 hours, and then calcine in a muffle furnace at 500°C for 5 hours to decompose the nitrates into metal oxides.

Experimental Setup (Plasma-Catalytic Reactor):

- Employ a Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) non-thermal plasma reactor.

- The reactor typically consists of a quartz tube with a high-voltage electrode and a ground electrode.

- Load the synthesized catalyst into the discharge zone of the reactor.

- Use mass flow controllers to introduce gaseous feeds: CO₂ and a carrier gas (e.g., N₂) saturated with toluene vapor by passing through a bubbler.

- Maintain the reactor at ambient pressure and a temperature of around 250°C.

Reaction and Analysis:

- Apply a high-voltage AC power to the DBD reactor to generate plasma. Systematically vary the discharge power (e.g., 20-100 W).

- Analyze the inlet and outlet gas composition using an online Gas Chromatograph (GC) equipped with a Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD) for permanent gases (H₂, CO, CO₂) and a Flame Ionization Detector (FID) for hydrocarbons.

- Calculate key performance metrics:

- Tar (Toluene) Conversion (%):

(1 - [C₇H₈]_outlet / [C₇H₈]_inlet) * 100 - Syngas Selectivity (%):

(Moles of H₂ or CO produced / Total moles of gaseous products) * 100

- Tar (Toluene) Conversion (%):

Protocol for Catalytic Supercritical Water Gasification of Coal

This protocol is adapted from studies on SCWG of coal integrated with hydrogen oxidation for autothermal operation [27].

Feedstock Preparation:

- Pulverize the coal feedstock (e.g., Hongliulin coal) to a particle size of less than 100 μm.

- To prepare a pumpable slurry, mix the coal powder with water and a stabilizer like xanthan gum (e.g., 0.1 wt%).

Catalyst Addition:

- Use an alkali catalyst such as potassium carbonate (K₂CO₃). Add it directly to the coal-water slurry.

Experimental Setup (SCW Fluidized Bed with Oxidation Zone):

- Use a continuous-flow SCWG reactor system capable of operating above 22.1 MPa and 374°C.

- The reactor system should be divided into a gasification zone and an oxidation zone.

- Pump the coal slurry and supercritical water into the gasification zone using high-pressure pumps.

- In a separate stream, inject compressed air directly into the oxidation zone of the reactor.

- The heat released from the exothermic oxidation of hydrogen and other gaseous products in the oxidation zone provides the necessary energy for the endothermic gasification reactions.

Reaction and Analysis:

- Conduct experiments at varying temperatures (e.g., 500-600°C), mass ratios of coal to SCW, and oxidation equivalent ratios.

- After the system reaches steady-state, sample the gaseous effluent.

- Analyze the gas composition using GC. Key metrics include:

- Gas Yield: Moles of syngas produced per kilogram of feedstock.

- Hydrogen Yield: Specifically, the moles of H₂ produced per kilogram of feedstock.

- Carbon Gasification Efficiency (CE):

(Carbon in gaseous products / Total carbon in feedstock) * 100

Research Workflow and Catalyst Synergy

The experimental protocols for evaluating catalysts in advanced gasification systems follow a logical progression from catalyst design to performance assessment. The diagram below illustrates the workflow and synergistic relationship between plasma and catalysts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This section lists key reagents, materials, and equipment essential for conducting experimental research in catalytic gasification, as derived from the cited protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Catalytic Gasification Studies.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Nickel Nitrate Hexahydrate | Precursor for active metal in catalyst synthesis [2] | Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, for preparing Ni-based and Ni-Fe bimetallic catalysts. |

| Iron Nitrate Nonahydrate | Precursor for secondary active metal [2] | Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O, used with Ni to form bimetallic catalysts for enhanced activity and carbon resistance. |

| Gamma-Alumina (γ-Al₂O₃) | High-surface-area catalyst support [2] | Porous γ-Al₂O₃ pellets or powder, providing a stable structure for dispersing active metals. |

| Potassium Carbonate (K₂CO₃) | Homogeneous alkali catalyst for SCWG [27] | Anhydrous K₂CO₃, catalyzes water-gas shift reaction to increase H₂ yield in supercritical water. |

| Toluene | Model tar compound for catalytic reforming studies [2] | C₇H₈, used as a representative of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in biomass tar. |

| Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) Reactor | Core component for non-thermal plasma generation [2] | Laboratory-scale reactor with high-voltage power supply for plasma-catalytic experiments. |

| High-Pressure Pump | Feeds slurry or water into SCWG reactors [27] [29] | HPLC or syringe pump capable of delivering fluids against very high pressures (>22 MPa). |

| Gas Chromatograph (GC) | Analyzes composition of product syngas [27] [2] | GC system equipped with TCD for H₂, CO, CO₂ and FID for hydrocarbons. |

The choice of gasification technology and catalyst is highly application-dependent. Fluidized bed systems benefit greatly from robust metal-based catalysts like Ni-Fe/Al₂O₃ for efficient tar cracking in conventional syngas production. SCWG is ideal for high-moisture feedstocks, where alkali catalysts significantly boost hydrogen yield, though materials and clogging present R&D challenges. Plasma gasification offers ultimate destruction efficiency for complex wastes, with plasma-catalysis synergy enabling high performance at lower temperatures.

The ongoing research into metal-based versus carbon-based catalysts underscores a trade-off between high activity/resistance (metal) and cost/durability (carbon). Future work should focus on developing more robust, cost-effective catalysts and integrating these advanced gasification systems with downstream synthesis processes for a comprehensive biorefinery approach.

The optimization of hydrogen yield and syngas ratio (H₂/CO) is a critical frontier in biomass gasification research, directly impacting the economic viability and downstream applicability of the produced syngas. The choice between metal-based and carbon-based catalysts represents a fundamental strategic decision, involving trade-offs between activity, cost, stability, and resistance to deactivation. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these catalyst families, focusing on their application-specific performance in enhancing hydrogen yield and optimizing the H₂/CO ratio for targeted industrial processes. We synthesize recent experimental data and methodologies to offer researchers a clear framework for catalyst selection and development.

Performance Comparison: Metal-Based vs. Carbon-Based Catalysts

The following tables summarize the performance characteristics of prominent metal-based and carbon-based catalysts, based on recent experimental studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Metal-Based Catalysts

| Catalyst Type | Experimental Conditions | H₂ Yield / Production Rate | Syngas (H₂/CO) Ratio | Key Performance Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni₃-Fe₁/Al₂O₃ (Bimetallic) | Plasma-catalytic CO₂ reforming of toluene; 250°C | High H₂ selectivity | N/A (High CO selectivity also reported) | Highest toluene conversion & syngas selectivity; strong CO₂ adsorption & carbon resistance | [2] |

| PdFe/CeO₂-SiO₂ (Nano-interface) | CO₂-assisted oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane | 508.1 μmol·g⁻¹·min⁻¹ | ~0.58 (CO yield: 879.1 μmol·g⁻¹·min⁻¹) | Optimized Pd-O-Ce interface maximizes syngas yield; one of the highest reported rates | [30] |

| CoFe-Based (Non-noble) | Ammonia decomposition | Efficient H₂ production reported | N/A | Cost-effective alternative to noble metals for H₂ production from ammonia | [31] |

| Millimeter Al Sphere (Non-catalytic) | Reaction with sub/supercritical water | 1245 mL g⁻¹ (theoretical) | N/A | Achieves full H₂ yield without catalysts or additives; enables integrated H₂/electricity/heat | [32] |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Carbon-Based Catalysts

| Catalyst Type | Experimental Conditions | H₂ Yield / Production Enhancement | Syngas (H₂/CO) Ratio | Key Performance Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe/K on Raw Biomass | Catalytic biomass gasification | Significantly enhanced syngas yield | Optimizable | Superior tar removal (>95%); generates in-situ reducing agents to activate Fe | [6] |

| KOH-Activated Carbon (AC) | Biomass gasification (tar removal) | N/A | N/A | High tar decomposition efficiency (91.75%) due to high porosity and surface area | [6] |

| Activated Biochar (A-Biochar) | Coupled with SiC membrane at 800°C | N/A | N/A | 96.4% tar conversion; multifunctional: adsorbs heavy tar, reforms light tar | [1] |

| Ni-Fe/Biochar | Biomass gasification | Increased syngas yield | Optimizable | Biochar acts as adsorbent and facilitates reduction of metal oxides | [6] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Plasma-Catalytic CO₂ Reforming over Ni-Fe/Al₂O₃

This protocol details the methodology for evaluating bimetallic metal-based catalysts, as described in [2].

- Catalyst Synthesis (Impregnation Method): Support γ-Al₂O₃ is impregnated with aqueous solutions of nickel nitrate (Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) and iron nitrate (Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O) to achieve desired Ni/Fe molar ratios (e.g., 3:1, 2:1, 1:1). The mixture is stirred, dried at 100°C for 12 hours, and subsequently calcined in air at a specified temperature (e.g., 500°C for 5 hours).

- Catalyst Characterization: The fresh catalysts are characterized using:

- X-Ray Diffraction (XRD): To identify crystalline phases (e.g., γ-Al₂O₃, NiAl₂O₄, Fe₂O₃).

- N₂ Physisorption: To determine textural properties like surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution, which typically show type IV isotherms indicative of mesoporous structures.

- Basicity Measurement: Using techniques like CO₂-TPD to quantify catalyst basicity, which correlates with CO₂ adsorption capacity.

- Plasma-Catalytic Testing: The reaction is performed in a Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) non-thermal plasma reactor at low temperatures (e.g., 250°C) and ambient pressure. Toluoid is used as a tar model compound. The feed gas consists of a controlled mixture of CO₂, toluene, and an inert carrier gas (e.g., Ar). The key operational parameters varied are:

- Discharge Power (e.g., 20-60 W): To study its effect on tar conversion and syngas selectivity.

- CO₂/C₇H₈ Molar Ratio: An optimal ratio of 1.5 was found to enhance performance.

- Product Analysis: The effluent gas is analyzed using online Gas Chromatography (GC) equipped with a TCD and/or FID to quantify the concentrations of H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄, and other light hydrocarbons. Toluene conversion and syngas selectivity are calculated from these data.

Protocol for Carbon-Supported Iron Catalyst Testing

This protocol outlines the preparation and testing of carbon-based catalysts, as per the study in [6].

- Catalyst Preparation:

- Support Preparation: Carbon supports are prepared from raw biomass (e.g., woody sawdust), biochar (from pyrolysis of sawdust), and chemically activated carbon (AC) using KOH.

- Metal Loading: The supports are impregnated with an aqueous solution of iron nitrate (Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O), with or without a potassium promoter (K₂CO₃). The mixture is then dried and calcined under a nitrogen atmosphere.

- Catalyst Characterization:

- Ultimate and Proximate Analysis: To determine the elemental composition (C, H, O, N) and ash content of the supports and catalysts.

- Surface Area and Porosity (BET): To measure the specific surface area, which is significantly higher for AC than for raw biochar.

- X-Ray Diffraction (XRD): To identify the oxidation state of iron (e.g., Fe₂O₃, Fe₃O₄, Fe⁰), which is influenced by the carbon support.

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): To examine the surface morphology and dispersion of active metals.

- Catalytic Gasification Testing: The gasification experiments are performed in a fixed-bed or fluidized-bed reactor system. Biomass feedstock (e.g., sawdust) is fed into the reactor operating at high temperatures (e.g., 700-900°C). The catalyst is placed in a separate catalytic zone. The key parameters studied are:

- Reaction Temperature

- Catalyst-to-Feedstock Ratio

- Product Analysis:

- Syngas Composition: Analyzed by Micro-GC to determine the concentrations of H₂, CO, CO₂, and CH₄, from which H₂/CO ratio and syngas yield are calculated.

- Tar Content: Quantified using methods like the tar protocol (cold solvent trapping) or online measurement, to determine tar removal efficiency.

Visualization of Workflows and Mechanisms

Catalyst Synthesis and Testing Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the general experimental pathway for developing and evaluating both metal-based and carbon-based catalysts.

Catalytic Reaction Mechanisms in Syngas Production

This diagram outlines the key mechanistic pathways for tar reforming and syngas production over different catalyst types.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Catalyst Development and Testing

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Source of active catalytic metal phases. | Iron(III) nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O), Nickel(II) nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O), Potassium carbonate (K₂CO₃) as promoter [6] [2]. |

| Catalyst Supports | Provide high surface area, stabilize metal particles, and can possess intrinsic catalytic activity. | γ-Alumina (γ-Al₂O₃) [2], SiO₂ [30], Biochar, Activated Carbon (AC) [6]. |

| Activating Agents | Chemically modify supports to create porosity and enhance surface area. | Potassium hydroxide (KOH) for chemical activation of carbon [6]. |

| Biomass Feedstock | Raw material for gasification; also used as catalyst precursor. | Woody sawdust (sieved) as a representative biomass [6]. |

| Tar Model Compounds | Simplify the study of complex tar reforming mechanisms. | Toluene, benzene, naphthalene as model tar compounds [2]. |

| Process Gases | Act as gasifying agents, reactive media, or purge gases. | CO₂ (for dry reforming), high-purity N₂ (as carrier/calcination atmosphere), O₂ (for oxidative processes) [2] [33]. |

| Analytical Standards | Calibration and quantification in analytical instruments. | Certified calibration gas mixtures (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄ in N₂) for Gas Chromatography (GC) [6] [2]. |