Navigating Transport Phenomena: A Comprehensive Guide to Successful Catalyst Scale-Up

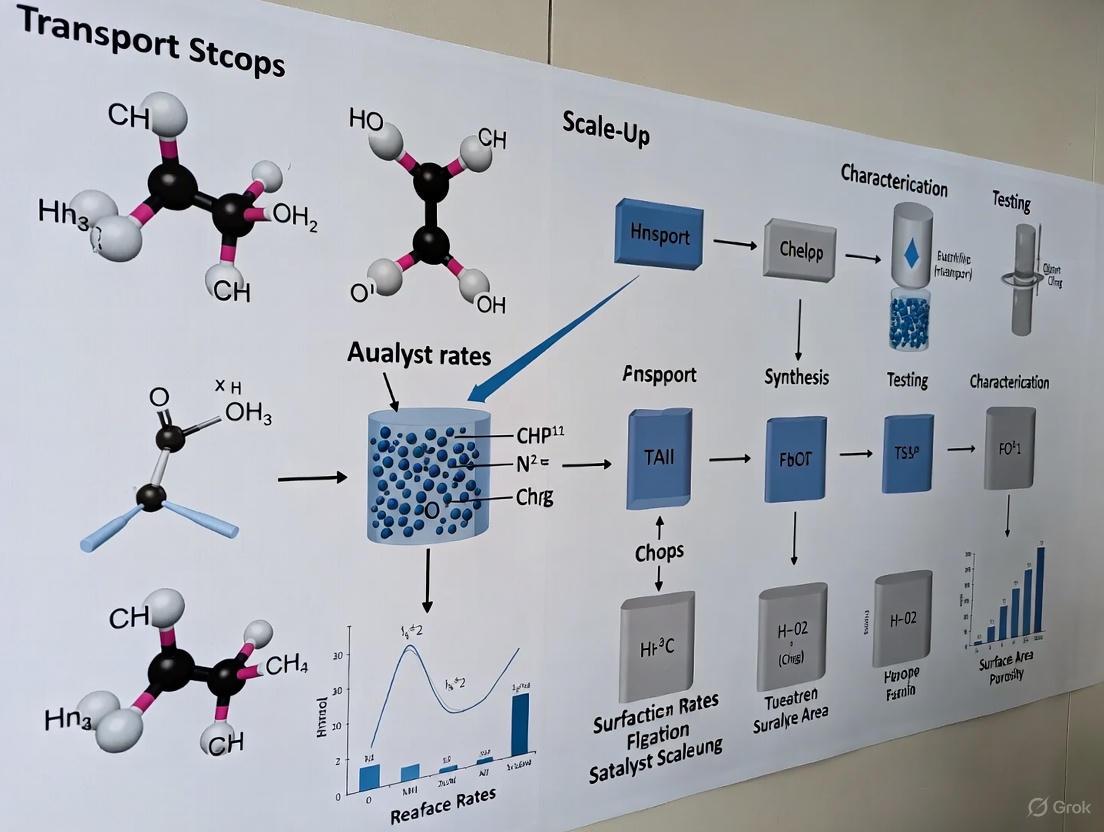

The scale-up of catalytic processes from laboratory to industrial scale presents significant challenges, primarily due to the complex interplay between reaction kinetics and transport phenomena.

Navigating Transport Phenomena: A Comprehensive Guide to Successful Catalyst Scale-Up

Abstract

The scale-up of catalytic processes from laboratory to industrial scale presents significant challenges, primarily due to the complex interplay between reaction kinetics and transport phenomena. This article provides a detailed framework for researchers and development professionals addressing mass and heat transfer limitations, mixing inefficiencies, and economic viability during scale-up. It explores foundational principles, advanced methodological tools like Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls, and validation techniques to ensure reproducible performance. By integrating theoretical knowledge with practical application guidelines, this resource aims to de-risk the scale-up process and accelerate the commercialization of robust catalytic processes, with particular relevance to pharmaceutical and biomedical applications where precision and reliability are paramount.

Understanding the Core Principles: Transport Phenomena in Catalytic Systems

The Critical Role of Mass and Heat Transfer in Heterogeneous Catalysis

FAQs: Core Concepts and Common Challenges

Q1: What are mass and heat transfer phenomena, and why are they critical in heterogeneous catalysis?

Mass transfer describes the physical movement of chemical species from one location to another, driven by potential gradients such as concentration or temperature differences [1]. Heat transfer involves the movement of thermal energy. In heterogeneous catalysis, these phenomena are critical because the reaction rate is often controlled not by the intrinsic chemical kinetics at the active site, but by the speed at which reactants can reach these sites or the efficiency with which reaction heat can be removed [2] [3]. In the kinetic region, the catalyst's intrinsic activity dominates. However, in subsequent light-off, thermodynamic, and homogeneous reaction regions, heat and mass transfer properties on the catalyst surface play a decisive role in the overall reaction rate [2].

Q2: How can I identify if my catalytic experiment is limited by mass or heat transfer?

Common indicators of transport limitations include:

- Activity Plateau: The reaction rate becomes independent of catalyst mass or stirring speed.

- Selectivity Shifts: Unexpected changes in product distribution, as some reaction pathways may be more sensitive to concentration gradients.

- Strong Sensitivity to Flow Dynamics: Significant changes in conversion or selectivity with variations in flow rate or stirring intensity [4]. For example, in one polyolefin hydrogenolysis study, different stirring strategies created differences of up to 85% in catalyst effectiveness [4].

- Temperature Dependence: An unusually low apparent activation energy can suggest that the process is dominated by diffusion, which has a weaker temperature dependence than chemical kinetics.

Q3: What is the "catalyst effectiveness factor," and how is it impacted by transport phenomena?

The catalyst effectiveness factor quantifies how effectively the internal surface area of a porous catalyst is being utilized. It is the ratio of the observed reaction rate to the rate that would occur if all interior active sites were exposed to the same conditions as the external surface. When internal mass transfer is slow, reactants cannot penetrate deep into the catalyst particle, leading to an effectiveness factor of less than 1 [3] [4]. Scaling up a catalyst from a laboratory powder to a formed technical body often introduces binders and creates complex pore networks, which can drastically alter this factor [3].

Q4: During catalyst scale-up, what are the most common transport-related pitfalls?

The primary pitfall is neglecting the profound impact of catalyst formulation and structuring. A catalytic powder tested in the lab is a very different material from a shaped technical catalyst body used in an industrial reactor. The process of forming the technical body with additives can drastically alter the mass and heat transfer properties, leading to performance that is not predictable from powder tests [3]. Other pitfalls include underestimating the power input required for effective mixing, especially in viscous systems [4], and failing to account for hot spot formation in highly exothermic or endothermic reactions.

Q5: How do advanced catalyst structures like POCS enhance mass and heat transfer?

Periodic Open Cellular Structures (POCS) are 3D-printed, ordered lattices (e.g., Tetrakaidekahedral or Diamond cells) designed to intensify transport processes. They enhance mass and heat transfer by:

- Creating Turbulence: Their complex solid matrix promotes intense mixing, thinning the boundary layer around the catalyst.

- Providing High Surface Area: They offer a large surface-to-volume ratio for reactions to occur.

- Ensuring Structural Uniformity: Their periodic nature allows for predictable flow and temperature fields, minimizing channeling and hot spots [5]. CFD studies show the Sherwood number (dimensionless mass transfer) for POCS follows a power-law dependence on the Reynolds number, confirming their enhanced transport capabilities [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Catalyst Effectiveness in a Slurry Reactor

Observed Symptom: Low conversion or unexpected product selectivity that changes significantly with stirring speed.

Investigation Protocol:

- Vary Agitation Rate: Conduct a series of experiments where you systematically increase the stirring rate (r.p.m.) while keeping all other parameters (temperature, pressure, catalyst loading) constant.

- Plot Results: Graph the reaction rate or conversion against the stirring rate.

- Interpret Data:

- If the reaction rate increases with stirring speed, your system is suffering from external mass transfer limitations. The mixing is insufficient to bring reactants to the catalyst surface efficiently [4].

- If the reaction rate plateaus and becomes independent of stirring speed, external mass transfer limitations have been overcome, and the system is likely operating in the kinetic regime or is limited by internal diffusion.

Solution:

- Increase Power Input: Switch from a magnetic stirrer to an overhead mechanical stirrer. Magnetic stirrers are typically unsuitable for highly viscous media (>\~1.5 Pa·s), while mechanical stirrers can handle viscosities up to 10^5 Pa·s [4].

- Optimize Impeller Design: Use impellers designed for high-viscosity mixing (e.g., helical ribbon impellers) to ensure the polymer melt or slurry is effectively mixed.

- Reference Parameter: For polyolefin melts (viscosity ~1-1,000 Pa·s), CFD modeling suggests targeting a dimensionless power number between 15,000 and 40,000 to maximize the catalyst effectiveness factor [4].

Problem 2: Rapid Catalyst Deactivation or Uncontrolled Reaction

Observed Symptom: Catalyst sintering, coking, or runaway reaction temperatures.

Investigation Protocol:

- Measure Temperature Gradients: Use a multi-point thermocouple or infrared thermography to map temperatures across the catalytic fixed-bed or reactor zone.

- Check for Hot/Cold Spots: Look for localized temperature deviations from the set point.

- Analyze Hydrodynamics: Use Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations or tracer studies to identify poor flow distribution, channeling, or stagnant zones.

Solution:

- Enhance Heat Transfer: Implement a catalyst structure with high thermal conductivity. Metallic Periodic Open Cellular Structures (POCS) are excellent for this, as their continuous solid matrix efficiently conducts heat away from active sites [5].

- Improve Flow Distribution: Redesign the reactor inlet or catalyst bed packing to ensure uniform flow. Structured catalysts like honeycombs or POCS inherently provide more uniform flow than random packed beds [5].

- Dilute Catalyst Bed: Use an inert, thermally conductive diluent to spread the reaction heat over a larger volume.

Problem 3: Performance Drop During Catalyst Scale-Up

Observed Symptom: A catalyst powder performs excellently in the lab, but its performance (activity, selectivity) drops significantly when formed into a shaped technical body for a pilot or industrial reactor.

Investigation Protocol:

- Characterize the Technical Body: Measure the porosity, pore size distribution, and effective diffusivity of the shaped catalyst pellet and compare it to the original powder.

- Test Different Particle Sizes: Perform laboratory tests with crushed catalyst pellets of different size fractions to isolate the effect of internal mass transfer.

- Calculate the Thiele Modulus: This dimensionless number will help quantify the extent of internal diffusion limitations.

Solution:

- Rational Formulation: Work with a catalyst manufacturer to strategically use binders and porogens that create optimal macropore networks to facilitate reactant access to the micro- and mesopores where active sites reside [3].

- Design Hierarchical Porosity: Engineer the catalyst with a bimodal or multimodal pore structure—large pores for rapid transport and small pores for high surface area.

- Consider Advanced Structures: For severe diffusion limitations, explore designing the catalyst as a hollow structure. For example, hollow CeO2 microspheres significantly enhance heat and mass transfer, reducing the T90 (temperature for 90% conversion) for methane combustion by 118°C compared to a solid counterpart [2].

Quantitative Data on Transport Correlations

The table below summarizes key dimensionless numbers and correlations used to quantify and design for mass and heat transfer in catalytic systems.

Table 1: Key Dimensionless Numbers for Transport Phenomena Analysis

| Dimensionless Number | Formula | Physical Meaning | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sherwood (Sh) / Nusselt (Nu) | Sh = km * L / D | Ratio of convective to diffusive mass/heat transfer | Correlated to Re and Sc for POCS: Power-law dependence (Re^0.33 to Re^0.67) found [5]. |

| Reynolds (Re) | Re = ρ * v * L / μ | Ratio of inertial to viscous forces | Determines flow regime (laminar/turbulent) in catalyst pores or around particles [5]. |

| Thiele Modulus (φ) | φ = L * √(k / Deff) | Ratio of reaction rate to diffusion rate in a catalyst particle | φ << 1: No internal diffusion limitations; φ >> 1: Strong limitations, low effectiveness. |

| Power Number (Np) | Np = P / (ρ * N^3 * d^5) | Relates power consumption to stirrer speed and geometry | A key scale-up parameter; target 15,000–40,000 for effective polyolefin melt mixing [4]. |

Table 2: Mass Transfer Performance of Different Catalyst Structures

| Catalyst Structure | Key Mass/Heat Transfer Feature | Reported Impact on Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Hollow CeO2 Microspheres | Enhanced diffusion and rapid heat release due to thin shell [2]. | T90 for CH4 combustion 118°C lower than solid CeO2 [2]. |

| Periodic Open Cellular Structures (POCS) | Intense mixing from periodic lattice; high surface area with manageable pressure drop [5]. | Higher gas-solid transfer rates than state-of-the-art honeycombs [5]. |

| Shaped Technical Body (vs. Powder) | Altered porosity and diffusion pathways due to additives and forming [3]. | Often the primary cause of performance drop during industrial scale-up [3]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Evaluating External Mass Transfer Limitations in a Slurry Reactor

Aim: To determine if the observed reaction rate is limited by the transport of reactants from the bulk fluid to the external surface of the catalyst particle.

Materials:

- Reactor System: Autoclave with mechanical overhead stirrer (magnetic stirrers are insufficient for viscous media) [4].

- Catalyst: Ru/TiO2 (or other relevant catalyst) with controlled particle size.

- Reactants: High-density polyethylene (HDPE, Mw = 200 kDa) or other substrate, Hydrogen gas.

Method:

- Baseline Test: Charge the reactor with a standard load of polymer and catalyst. Initiate the reaction (e.g., at 498 K, 20 bar H2) with a baseline stirring speed (e.g., 50 rpm).

- Stirring Variation: Repeat the experiment under identical conditions (temperature, pressure, catalyst loading, reaction time) but systematically increase the stirring speed (e.g., 100, 200, 300 rpm).

- Analysis: Quantify the conversion and product distribution for each experiment via Gas Chromatography (GC) or Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC).

- Data Interpretation: Plot conversion or reaction rate versus stirring speed. A positive correlation indicates external mass transfer limitations. A plateau indicates these limitations have been minimized.

Protocol B: Assessing Internal Mass Transport in a Porous Catalyst

Aim: To investigate the impact of particle size and internal pore structure on catalyst effectiveness.

Materials:

- Catalyst Samples: The same catalyst composition prepared in different forms: a) fine powder, b) crushed particles of various sieve fractions (e.g., 0.1-0.3 mm, 0.3-0.6 mm), c) formed technical extrudates or spheres.

- Test Reaction: A standard, well-understood probe reaction (e.g., CO oxidation or a simple hydrocarbon hydrogenation).

Method:

- Kinetic Testing: Conduct the probe reaction with each catalyst sample under identical, well-controlled conditions in a plug-flow reactor.

- Measurement: Measure the apparent reaction rate for each particle size.

- Calculation: For each particle size, calculate the observed reaction rate per mass of catalyst. The catalyst effectiveness factor (η) can be estimated as the observed rate for a large particle divided by the observed rate for the finest powder (where η ≈ 1).

- Modeling: Use the Thiele modulus analysis to model the relationship between particle size and effectiveness factor, which allows for the estimation of the effective diffusivity (Deff) within the catalyst particle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Investigating Transport Phenomena

| Item | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Overhead Stirrer | Provides sufficient torque to mix highly viscous reaction media (e.g., polymer melts) [4]. | Critical for systems with viscosity > ~1.5 Pa·s; magnetic stirrers are ineffective. |

| Ru/TiO2 Catalyst | A state-of-the-art catalyst used for model reactions like polyolefin hydrogenolysis [4]. | Useful as a benchmark system for studying transport effects in complex media. |

| Cerium Nitrate Hexahydrate (Ce(NO3)3·6H2O) | Precursor for synthesizing model catalyst structures like hollow CeO2 microspheres [2]. | Allows investigation of how morphology (e.g., hollow vs. solid) impacts heat and mass transfer. |

| Silica Microspheres | Used as a sacrificial template in the synthesis of hollow catalyst structures [2]. | Template size and monodispersity control the final catalyst shell properties. |

| 3D-Printed POCS Supports | Periodic Open Cellular Structures used as structured catalyst supports to intensify transport [5]. | Enable the study of the relationship between defined geometry and transport coefficients. |

| Rheometer | Characterizes the viscosity of reaction media (e.g., polymer melts) as a function of shear rate and temperature [4]. | Essential data for accurate CFD simulation and reactor design. |

Diagnostic Visualization

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing common mass and heat transfer problems in catalytic experiments, based on the troubleshooting guides and FAQs.

Diagram: Diagnostic Pathway for Transport Limitations

Analyzing the Five Sequential Steps of Heterogeneous Reactions

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why does my catalyst's performance drop significantly when scaling up from a laboratory reactor to a pilot plant?

This is a common challenge often caused by changes in transport phenomena, the physical processes that move reactants and products. At a small scale, mixing is highly efficient, ensuring reactants easily reach the catalyst's active sites. In larger reactors, inadequate mixing can create mass transfer limitations, meaning reactants cannot access the interior of catalyst pellets fast enough, or heat transfer issues can lead to damaging hotspots [6] [7]. The intrinsic chemical reaction might be fast, but the overall rate becomes limited by these physical transport processes [8].

2. My reaction works with a model feedstock but fails with a complex, real-world mixture. What could be wrong?

This often points to catalyst deactivation or pore accessibility issues. Model feedstocks are pure and simple, while complex mixtures can contain species that poison the catalyst by strongly adsorbing to and blocking active sites [9] [10]. Furthermore, large molecules in a real feedstock might be physically unable to diffuse into the catalyst's pores where most active sites are located, a problem known as internal mass transport limitation [4] [9]. Testing with a model compound that has a similar molecular structure to key constituents in your complex feedstock can help identify this issue early [10].

3. How can I determine if my experiment is suffering from mass transfer limitations?

A key diagnostic method is to run the reaction at the same conditions but with varying stirring or agitation rates. If the reaction rate increases with faster stirring, you are likely experiencing external mass transfer limitations, where reactants are not reaching the catalyst particle's surface quickly enough [4]. Another method is to grind the catalyst to a finer powder and repeat the test. If the rate increases, it suggests internal mass transfer limitations within the catalyst pores are a problem [4] [9].

4. What is the difference between a "sensible" and an "insensible" reaction, and why does it matter?

A sensible reaction produces easily measurable changes, such as temperature, pressure, or composition, making it straightforward to monitor. An insensible reaction, however, involves subtle surface processes like the rearrangement of adsorbed species with no significant change in bulk properties, making it difficult to observe with conventional techniques [10]. This distinction is crucial for selecting the right analytical tools to study your catalytic system effectively [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Reaction Rates and Selectivity During Scale-Up

Description The catalyst demonstrates excellent activity and selectivity in small, laboratory-scale batch reactors but shows unpredictable and lower performance when moved to a larger continuous flow reactor.

Diagnosis and Solution

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Analyze Mixing | Evaluate the power number (a dimensionless parameter related to mixing intensity) in the new reactor. For highly viscous systems like polymer melts, a power number between 15,000–40,000 may be required for optimal performance [4]. | Maximizes the catalyst effectiveness factor by ensuring sufficient extension of the gas-liquid interface and access to catalyst particles, overcoming external mass transfer limitations [4]. |

| 2. Check Flow Regime | In continuous systems, verify the flow regime (e.g., laminar vs. turbulent). Use Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations to identify dead zones or channeling [8]. | Ensures a uniform residence time for all reactant molecules, preventing side reactions that degrade selectivity. Classical theories may not explain behavior in novel reactor geometries [7]. |

| 3. Pilot Testing | Conduct pilot-scale testing before full-scale production. This intermediary step helps identify and rectify scale-dependent issues [6]. | De-risks the scale-up process by providing invaluable data on heat and mass transfer at a larger scale, minimizing costly mistakes [6]. |

Problem: Rapid Catalyst Deactivation

Description The catalyst loses its activity and/or selectivity over a short period, leading to frequent shutdowns for regeneration or replacement.

Diagnosis and Solution

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Identify Poison | Analyze the feedstock for potential catalyst poisons. Common poisons include Group V, VI, and VII elements (S, O, P, Cl) and species with multiple bonds (e.g., CO) [9]. | Prevents active sites from being permanently blocked by strongly adsorbing species, thereby extending catalyst lifetime [9]. |

| 2. Check for Fouling | Examine spent catalyst for coking (deposition of carbonaceous solids) or fouling (deposition of other materials). This is common in hydrocarbon processing [9]. | Identifies if deactivation is due to physical blockage of pores and active sites, which can sometimes be reversed through regeneration cycles [9]. |

| 3. Verify Thermal Control | Monitor for hotspots in the reactor, which can accelerate sintering (migration and agglomeration of metal particles) [6] [9]. | Maintains the high dispersion of active metal sites. Sintering reduces the catalyst's surface area and number of active sites, leading to permanent deactivation [9]. |

Key Experimental Data and Protocols

Quantitative Parameters for Mixing in Viscous Systems

The table below summarizes critical parameters identified for effective mixing in high-viscosity polymer melt reactions, which is a key transport phenomenon challenge [4].

| Parameter | Typical Value / Range | Impact on Catalyst Effectiveness | Applicable Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power Number | 15,000 - 40,000 | Increases effectiveness factor by up to 85% by maximizing interface extension [4]. | Viscosity range of 1–1,000 Pa·s |

| Melt Viscosity | ~500 Pa·s (HDPE), ~320 Pa·s (PP) | High viscosity dictates laminar flow, requiring powerful mechanical stirring [4]. | Shear rates equivalent to >15 r.p.m. |

| Stirring Equipment | Mechanical Stirrer | Functional up to 105 Pa·s; essential for high Mw polyolefins [4]. | Viscosity > ~1.5 Pa·s |

Protocol: Diagnosing Mass Transfer Limitations

Objective: To determine if the observed reaction rate is limited by the intrinsic chemical kinetics or by mass transfer.

Materials:

- Standard laboratory stirred reactor

- Catalyst sample (two forms: powdered and pelletized)

- High-purity reactants

Method:

- External Limitation Test: Run the reaction at a standard set of conditions (temperature, pressure, catalyst mass). Repeat the experiment, systematically increasing the stirring rate while keeping all other parameters constant.

- Internal Limitation Test: Run the reaction with the standard catalyst pellet form. Then, repeat the experiment using the same catalyst that has been crushed into a fine powder.

- Data Analysis: Plot the reaction rate against the stirring rate and against the catalyst particle size.

Interpretation:

- If the reaction rate increases with stirring speed, the system is suffering from external mass transfer limitations [4].

- If the reaction rate is higher with powdered catalyst than with pellets, the system is suffering from internal mass transfer limitations [4] [9].

- If the rate remains unchanged, the system is likely operating in the kinetic regime, where the intrinsic chemical reaction is the rate-limiting step.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Stirrer | Provides the necessary power to mix highly viscous reaction media and ensure reactants reach catalyst surfaces [4]. | Magnetic stirrers are insufficient for viscosities > ~1.5 Pa·s; essential for polymer melts [4]. |

| Porous Catalyst Support (e.g., Alumina, Zeolite) | Maximizes surface area and disperses active metal sites, providing more locations for the reaction to occur [9] [10]. | Pore size must be selected to allow reactant and product molecules to access the interior active sites [4] [9]. |

| Model Feedstocks (e.g., n-Heptane, Phenol) | Pure compounds used for initial catalyst screening and mechanistic studies due to their well-defined reactivity [10]. | Allows for precise evaluation of catalyst performance before moving to more complex, real-world feedstocks [10]. |

| Promoters (e.g., Alumina in Ammonia Synthesis) | Substances added to the catalyst to improve its activity, selectivity, or stability [9]. | In ammonia synthesis, alumina promotes stability by slowing the sintering of the iron catalyst particles [9]. |

Process Visualization

The Impact of Scale on Mixing Regimes and Flow Dynamics

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How does reactor scale-up directly impact the mixing and flow within my reactor? As you move from a laboratory-scale reactor to a larger pilot or industrial-scale reactor, the interplay between chemical reactions and physical transport phenomena changes. The flow regime (e.g., segregated, vortex, or engulfment) is highly dependent on the reactor's geometry and the flow rate, characterized by the Reynolds number (Re) [11] [12]. During scale-up, maintaining the same Re is often not feasible or sufficient, as the increased dimensions can alter the flow regime, thereby affecting mixing efficiency, heat transfer, and ultimately, your reaction yield and selectivity [13].

2. I am achieving excellent yields in my lab-scale T-mixer, but the performance drops in the scaled-up pilot plant. What could be the cause? This is a common scale-up challenge. In microreactors, an "engulfment" flow regime, which significantly enhances mixing by increasing vorticity, is often achieved at specific Reynolds numbers (e.g., Re ~200 for a T-mixer) [12]. During scale-up, if the reactor geometry and flow rates are not carefully designed to maintain this engulfment regime, the system may fall back into a "segregated" regime where mixing is slow and relies solely on diffusion [11] [14]. This reduces the effective contact between reactants, lowering your yield.

3. What are the critical parameters to control when scaling up a catalytic reaction? The primary challenge is managing the coupling between reaction kinetics and transport phenomena (mass and heat transfer), which scales differently with reactor size [13] [15]. Key parameters to control include:

- Flow Regime: Ensure mixing is not compromised by maintaining dynamic similarity (e.g., via dimensionless numbers) [16].

- Heat Transfer: Avoid hot spots that can degrade your catalyst or product [6].

- Mass Transfer: Ensure reactants can efficiently reach the active sites on your catalyst, which becomes more difficult as particle size or reactor dimensions increase [15].

4. Can advanced modeling help me predict mixing issues during scale-up? Yes, modern model-assisted scale-up is a powerful strategy. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modeling can probe the hydrodynamics and predict flow regimes at different scales [17] [13]. This can be complemented by Phenomenological Models, which use simplified hydrodynamics to quickly scope process conditions. Using these tools, you can identify potential mixing issues and optimize the reactor design before building expensive pilot plants [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Product Yield and Selectivity After Scale-Up

Potential Cause: Change in Flow Regime Leading to Poor Mixing. The mixing quality in a reactor is dictated by its flow regime. Scaling up often changes the Reynolds number and the geometry, which can shift the system from an efficient mixing regime (e.g., engulfment) to an inefficient one (e.g., segregated) [11] [14].

Diagnosis and Verification:

- Calculate the Reynolds Number (Re): Compare the Re between your lab-scale and pilot-scale reactors. The Re is defined as (Re = \frac{\rho U d}{\mu}), where (\rho) is density, (U) is bulk velocity, (d) is hydraulic diameter, and (\mu) is dynamic viscosity [11].

- Use Tracer Experiments: Conduct flow visualization experiments, such as Planar Laser Induced Fluorescence (PLIF), to visually identify the flow pattern (segregated, vortex, engulfment) in your new reactor [14].

Solution:

- Optimize Reactor Geometry: Consider using mixer designs that promote better mixing at lower Reynolds numbers. For example, X-micromixers can exhibit an engulfment regime at a lower Re (e.g., as low as Re=48) compared to some T-mixers [11].

- Adjust Operational Parameters: If possible, modify the flow rate to move the operation into a more favorable flow regime for mixing. Be aware that a higher flow rate improves mixing but reduces residence time, which may require a trade-off [11].

Experimental Protocol: Mapping Flow Regimes in a T-Mixer

- Objective: To experimentally identify the transition between flow regimes (segregated, vortex, engulfment) in a T-jets mixer [14].

- Materials:

- T-shaped mixer (with a defined mixing chamber width

W, injector widthw, and chamber depthd). - Two syringe or piston pumps for precise fluid delivery.

- Deionized water.

- Rhodamine 6G fluorescent dye or a similar tracer.

- Planar Laser Induced Fluorescence (PLIF) setup, including a laser sheet and a high-resolution camera.

- T-shaped mixer (with a defined mixing chamber width

- Method:

- Set up the T-mixer and align the laser sheet to illuminate the mixing chamber's central plane.

- Pump clear water through one inlet and a Rhodamine 6G solution through the other at a fixed, low flow rate (low Re).

- Capture the PLIF image. You should observe two distinct, parallel streams with minimal interdiffusion—this is the segregated regime.

- Gradually increase the flow rate (and thus the Re) while capturing new PLIF images.

- Observe the onset of vortical structures within each stream. This characterizes the vortex regime.

- Further increase the Re until these structures evolve to engulf fluid from both streams, drastically increasing the interfacial area and mixing. This is the engulfment regime, marked by a sudden increase in mixing quality [14].

Problem: Catalyst Performance Drop at Larger Scale

Potential Cause: Intensified Heat and Mass Transfer Limitations. At a larger scale, the same chemical reaction may be limited by the rate at which reactants can diffuse to the catalyst surface (mass transfer) or the rate at which heat can be removed from the catalyst pellet (heat transfer). This can lead to lower observed reaction rates, hot spots, and altered selectivity [6] [15].

Diagnosis and Verification:

- Test for Mass Transfer Limitations: Perform an experiment with different catalyst particle sizes while keeping the total catalyst mass constant. If the reaction rate increases with smaller particle size, your process is likely suffering from internal mass transfer limitations [18].

- Monitor for Temperature Gradients: Use thermocouples at different radial and axial positions in the reactor to identify hot or cold spots that were not present at the smaller scale.

Solution:

- Redesign Catalyst Pellet: Use smaller catalyst pellets or design pellets with shapes and pore structures that enhance internal mass transfer [15].

- Improve Reactor Design: Modify the reactor internals or operating conditions to improve bulk fluid motion and heat exchange. Pilot-scale testing is crucial for identifying these issues [6].

Data Tables for Mixing Regimes and Reactor Performance

Table 1: Characteristic Flow Regimes and Mixing Performance in Different Microreactor Geometries

| Reactor Geometry | Flow Regime | Reynolds Number (Re) Range | Key Mixing Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-Microreactor [11] | Segregated | < 48 | Parallel streams; mixing by diffusion only; poor performance. |

| Engulfment | 48 - 300 | Single steady vortex; increased contact area; sharp rise in mixing quality. | |

| Unsteady | > 300 | Periodic oscillation; vortex merging/breakup. | |

| T-Mixer [14] [12] | Segregated | Low Re | Steady, parallel flow of jets after impingement. |

| Vortex | Medium Re | Existence of helicoidal vortices within each jet stream. | |

| Engulfment | ~200 (for some geometries) | Vortical structures engulf fluid from both streams; high mixing index. |

Table 2: Impact of Flow Regime on a Model Chemical Reaction in an X-Microreactor Based on the reaction between ascorbic acid and methylene blue with varying hydrochloric acid concentration and kinetic constant (k) [11].

| [HCl] (mol/L) | Kinetic Constant, k | Reynolds Number (Re) | Degree of Mixing (δm) | Observed Reaction Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.73 | Low | 50 | ~0.4 | Low |

| 0.73 | Low | 150 | ~0.9 | High |

| 2.19 | High | 50 | ~0.4 | Medium |

| 2.19 | High | 150 | ~0.9 | High (Kinetics-limited) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Flow Regime Studies

| Item | Function / Role in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Rhodamine 6G Dye | A fluorescent tracer used in Planar Laser Induced Fluorescence (PLIF) to visualize and quantify fluid streams and mixing efficiency [14]. |

| Aqueous Methylene Blue & Ascorbic Acid Solutions | A model redox reaction system where the colored methylene blue becomes colorless upon reaction. Used to visually monitor reaction progress and yield as a function of mixing [11]. |

| Precision Syringe Pumps | To deliver fluids at precisely controlled, pulsation-free flow rates, which is critical for maintaining stable flow regimes and achieving reproducible results [14]. |

| Microreactor Chips (T-, Y-, X-geometry) | The core test platform, often with square or rectangular channels, used to study the fundamental impact of geometry on flow hydrodynamics and mixing [11] [12]. |

Process Flow and Relationships

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers address common challenges in catalyst characterization, a critical foundation for tackling transport phenomena in catalyst scale-up.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary techniques for complete catalyst pore texture analysis? A complete characterization requires a combination of techniques to cover the full range of pore sizes [19]. No single method can effectively characterize micropores, mesopores, and macropores. The recommended suite of methods includes:

- Surface Area: BET method via gas adsorption (e.g., N₂ at 77 K).

- Pore Volume: Incipient wetness method or picnometry.

- Micropore Analysis: t-plot or as-plot methods.

- Mesopore Analysis: BJH method from gas adsorption or mercury porosimetry.

- Macropore Analysis: Mercury porosimetry.

FAQ 2: How does pore size impact mass transfer and catalyst effectiveness? Pore size directly governs mass transport mechanisms and effectiveness factors, especially when scaling up reactions [19] [4].

- Macropores (>50 nm): Bulk diffusion dominates; generally lower resistance to mass transfer.

- Mesopores (2-50 nm): Knudsen diffusion dominates; can create transport limitations for larger molecules.

- Micropores (<2 nm): Configural or molecular diffusion dominates; significant transport limitations can occur, and pore mouth blocking by coke is a common deactivation mechanism. For polymer melts, very high viscosities can exacerbate these limitations and reduce catalyst effectiveness [4].

FAQ 3: Why is catalyst texture important for scaling up polyolefin recycling processes? In highly viscous processes like polyolefin hydrogenolysis, ineffective mixing creates major transport limitations, reducing catalyst effectiveness by up to 85% [4]. The polymer melt's extremely high viscosity (up to 1000 Pa·s) hinders reactant access to active sites. Scaling up requires mechanical stirring strategies to extend the H₂–melt interface and ensure catalyst particles are accessible, which is unachievable with standard magnetic stirrers [4].

FAQ 4: What are common methods for determining total pore volume and particle density?

- Incipient Wetness Impregnation: The solid is impregnated with a liquid until pores are filled; pore volume equals the liquid volume adsorbed. This is a precise and practical method [19].

- Picnometry: Measures true density and particle density using different fluids [19].

- Helium Picnometry: Helium penetrates all cavities, measuring true density.

- Mercury Picnometry: At low pressure, mercury only penetrates pores larger than ~15,000 nm, measuring particle density. Total pore volume is calculated from these densities.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low catalyst effectiveness factor in a slurry-phase reactor. Potential Causes and Solutions:

- External Mass Transfer Limitation: Agitation may be insufficient to reduce the boundary layer around catalyst particles.

- Solution: Increase stirring rate or power input. For high-viscosity fluids like polymer melts, use mechanical stirring and aim for a high power number (e.g., 15,000-40,000) to maximize the gas-liquid-catalyst interface [4].

- Internal Mass Transfer Limitation: Reactants cannot access the interior of catalyst particles.

- Solution: Analyze pore size distribution. If most surface area is in micropores, consider developing catalysts with hierarchical pore structures or larger mesopores to improve diffusivity.

Problem: Inconsistent surface area measurements between different instruments. Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Sample Preparation: Incomplete outgassing leaves contaminants blocking pores.

- Solution: Standardize and rigorously document outgassing procedure (temperature, time, vacuum level) for all samples.

- Methodology Differences: Using different analytical gases or models.

- Solution: Use the same standard method, typically N₂ adsorption at 77 K with the BET model for surface area. For very low surface areas (<1 m²/g), Kr or Ar adsorption may be used [19].

Problem: Rapid catalyst deactivation by coking. Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Pore Mouth Blocking: Prevalent in microporous and mesoporous catalysts.

- Solution: Design catalyst texture with larger mesopores or macropores to facilitate access to acid sites and allow coke precursors to escape. Deactivation is greatly affected by pore size [19].

Experimental Protocols for Key Characterization Methods

Protocol 1: Determining Surface Area via BET Method

This protocol outlines the BET method for determining the specific surface area of a porous catalyst using nitrogen adsorption at 77 K [19].

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Nitrogen Gas | Analytical adsorbate gas for generating the adsorption isotherm. |

| Liquid Nitrogen | Cryogenic bath to maintain a constant temperature of 77 K during adsorption. |

| Helium Gas | Used for dead space volume measurement and potentially for picnometry. |

| Catalyst Sample | The porous solid material to be characterized. |

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Weigh an appropriate amount of catalyst sample into a clean, pre-tared analysis tube. The sample mass should be sufficient to provide a total surface area within the instrument's optimal range.

- Degassing: Seal the tube and heat it under vacuum to a predetermined temperature (e.g., 150-300°C) for a specified time to remove all physisorbed contaminants (water, vapors) from the surface and pores.

- Cooling and Immersion: After cooling, the analysis tube is immersed in a liquid nitrogen bath (77 K).

- Adsorption Isotherm: Admit known amounts of nitrogen gas into the sample tube. Measure the equilibrium pressure after each dose to construct the adsorption isotherm—the volume of gas adsorbed versus relative pressure.

- BET Calculation: Apply the BET equation to the linear region of the isotherm (typically between P/P₀ = 0.05 - 0.30) to calculate the monolayer capacity. The specific surface area is then calculated from this value.

Protocol 2: Determining Pore Size Distribution by Mercury Porosimetry

This protocol describes how to determine meso- and macropore volume and size distribution by forcing mercury into the pores of a solid under pressure [19].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Pre-dry the catalyst sample and place it into a sealed vessel called a penetrometer.

- Evacuation: The sample cell is evacuated to remove air from the sample's open pores.

- Mercury Filling: The cell is filled with mercury at low pressure. Due to mercury's high surface tension and non-wetting properties, it does not spontaneously enter the pores.

- Pressure Ramping: Apply increasing hydraulic pressure to the mercury, forcing it into the pores.

- Volume Intrusion: The volume of mercury intruded into the pores is measured as a function of the applied pressure.

- Data Analysis: The Washburn equation,

P=(2γcosθ)/rp, is used to convert pressure to pore radius, generating a pore size distribution.

Table: Comparison of primary techniques for catalyst pore texture characterization.

| Property | Primary Technique(s) | Typical Range | Key Principles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Area | BET Gas Adsorption [19] | 1 - 1000+ m²/g | Measures volume of gas adsorbed as a monolayer; based on N₂ physisorption at 77 K. |

| Micropore Volume | t-plot, as-plot [19] | < 2 nm | Analyzes adsorption data to distinguish micropore filling from surface coverage. |

| Mesopore Volume/Size | BJH Method, Hg Porosimetry [19] | 2 - 50 nm | Based on capillary condensation (BJH) or mercury intrusion under pressure (Hg). |

| Macropore Volume/Size | Mercury Porosimetry [19] | > 50 nm | Measures volume of mercury forced into large pores under high pressure. |

| Total Pore Volume | Incipient Wetness, Picnometry [19] | All pores | Pores filled with liquid; or calculated from particle and true density. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key reagents, materials, and instruments used in catalyst texture characterization.

| Item | Function / Role in Characterization |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Gases (N₂, Ar, Kr) | Adsorbates for surface area and pore volume measurements via physisorption [19]. |

| Liquid Nitrogen | Standard cryogen for maintaining 77 K temperature during N₂ adsorption experiments [19]. |

| Helium Gas | Used for dead space volume measurement in adsorption and for true density via pycnometry [19]. |

| Mercury | Non-wetting fluid used in high-pressure porosimetry to intrude into meso- and macropores [19]. |

| Micromeritics 3Flex/ASAP | Advanced gas adsorption instruments for surface area and micro/mesopore analysis [20]. |

| Micromeritics AutoPore | Mercury porosimeter for meso- and macropore size distribution [20]. |

| FT4 Powder Rheometer | Analyzes powder flow and fluidization characteristics, crucial for catalyst formulation and reactor design [20]. |

The Path from Pore Texture to Transport Phenomena

Understanding catalyst texture is the first step in diagnosing and solving transport limitations. Pore size distribution and surface area data directly feed into models for predicting catalyst effectiveness factors, especially when scaling up from ideal lab conditions to realistic process fluids like polymer melts [4]. The characterization protocols and troubleshooting guides provided here are essential for linking intrinsic catalyst properties to their performance in industrial applications.

Viscosity and Non-Newtonian Behavior in Complex Reaction Media

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Unexpected Flow Behavior During Reaction Scale-Up

Issue: A reaction mixture that was easily manageable in the laboratory exhibits poor flow, excessive pressure drop, or phase separation when scaled up to a pilot or production reactor.

Explanation: This is a classic symptom of a non-Newtonian fluid whose viscosity is dependent on the shear conditions, which change dramatically with scale. In a large reactor, shear rates can be significantly lower, causing the viscosity of a shear-thinning fluid to increase and resist flow [21] [6].

Solution:

- Characterize Rheology: Determine if your fluid is Newtonian or non-Newtonian by measuring its viscosity across a wide range of shear rates (e.g., from 1 s⁻¹ to over 10,000 s⁻¹) using a rotational rheometer or microfluidic viscometer [21] [22].

- Map Process Shear Rates: Calculate or estimate the shear rates present in your lab-scale setup and your large-scale reactor.

- Match Viscosity: Ensure you are comparing viscosities at the same, process-relevant shear rate, not just the same temperature [21]. A fluid that appears thin in a high-shear lab mixer may be very thick in a low-shear large tank.

Problem 2: Inconsistent Product Quality or Reaction Rates

Issue: Catalyst performance or product distribution varies between batches despite identical temperature and concentration profiles.

Explanation: Non-Newtonian flow can lead to poor mixing and mass transfer issues. In a shear-thinning fluid, stagnant zones with very high viscosity can form in parts of the reactor, preventing reactants from reaching the catalyst surface efficiently. This creates localized variations in concentration and reaction rate [6] [23].

Solution:

- Identify Mass Transfer Limitations: Conduct experiments at different agitation speeds. If the reaction rate or product yield changes with mixing speed, it indicates a mass transfer limitation exacerbated by the fluid's rheology.

- Optimize Mixing & Reactor Design: Use the fluid's viscosity profile to design agitators and baffles that ensure adequate mixing throughout the relevant shear rate range. Consider static mixers for continuous processes [6].

Problem 3: Difficulty in Pumping and Filtration

Issue: The reaction slurry or broth requires unexpectedly high pressure to pump or filter.

Explanation: The apparent viscosity of a non-Newtonian fluid is not a single value. Pumping and filtration impose specific, and often high, shear rates. A fluid characterized at low shear may behave completely differently under these conditions. Yield-stress fluids (a sub-class of non-Newtonians) require a minimum pressure to initiate flow at all [21] [23].

Solution:

- Measure Viscosity at High Shear: Use a capillary viscometer or a rheometer capable of high shear rates to characterize the fluid under conditions mimicking the pumping (shear rates of 100-10,000 s⁻¹) and filtration processes [22].

- Model the Process: Use the power-law or other rheological models to predict pressure drops in pipes and across filter cakes, ensuring your equipment is appropriately specified [23].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My medium is a complex mixture of cells, proteins, and nutrients. Is it Newtonian or non-Newtonian? Most complex biological and chemical mixtures are non-Newtonian [21]. For example, filamentous fermentation broths and concentrated protein solutions often exhibit shear-thinning (pseudoplastic) behavior, where viscosity decreases as the shear rate increases [24] [22]. The only way to be certain is through rheological characterization.

Q2: Why does my catalyst perform differently in the lab vs. the pilot plant, even when we control temperature and concentration? The primary reason is often differences in transport phenomena—heat and mass transfer—which are scale-dependent [6] [15]. On a small scale, mixing is highly efficient. Upon scale-up, if your reaction medium is non-Newtonian, mixing efficiency can drop significantly in certain zones of the reactor. This leads to hotspots, concentration gradients, and reduced access to catalytic sites, altering performance [6].

Q3: What is the most critical mistake in handling non-Newtonian fluids during scale-up? Assuming viscosity is a constant value. The most common error is reporting a "viscosity" measured at a single, arbitrary shear rate that does not represent the conditions in the large-scale process. This number is useless for design and troubleshooting. Always report the full flow curve (viscosity vs. shear rate) [21] [22].

Q4: How can I quickly screen for non-Newtonian behavior? A simple qualitative test is to measure the time for a fluid to drain from a pipette or cup at different suction or pressure levels. If the flow rate is not proportional to the applied force, the fluid is likely non-Newtonian. For quantitative data, a rheometer is required.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Determining Newtonian vs. Non-Newtonian Behavior

Objective: To characterize the fundamental flow behavior of a reaction medium and fit it to a rheological model.

Methodology:

- Instrument: Use a rotational rheometer with a cone-and-plate or parallel plate geometry, or a capillary viscometer [22].

- Sample Preparation: Ensure the sample is homogeneous and representative. Load carefully to avoid air bubbles.

- Shear Rate Ramp: Program the instrument to sweep through a range of shear rates relevant to your process (e.g., 0.1 s⁻¹ to 1000 s⁻¹). Allow sufficient time at each step for the stress to stabilize.

- Data Collection: Record the shear stress (τ) and calculated viscosity (η) at each shear rate (ẏ). Perform measurements at a constant, process-relevant temperature.

- Analysis: Plot viscosity vs. shear rate and shear stress vs. shear rate.

Data Interpretation:

- Newtonian: A horizontal line on the viscosity vs. shear rate plot. Shear stress is directly proportional to shear rate [21].

- Shear-Thinning: Viscosity decreases with increasing shear rate. The shear stress vs. shear rate plot is non-linear, curving downward [21].

- Shear-Thickening: Viscosity increases with increasing shear rate. The shear stress vs. shear rate plot curves upward [21].

Rheological Model Fitting: For shear-thinning fluids, the Power-Law (Ostwald-de Waele) model is often used: τ = m * (ẏ)ⁿ Where:

- τ = Shear Stress (Pa)

- ẏ = Shear Rate (s⁻¹)

- m = Consistency Index (Pa·sⁿ)

- n = Flow Behavior Index (dimensionless; n<1 for shear-thinning)

Quantitative Data from Representative Fluids

Table 1: Viscosity Measurements of a Sucrose Solution (Newtonian Surrogate) at 20°C [22]

| Shear Rate (s⁻¹) | Viscosity (cP) | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | 2.0 | Rotational Rheometer |

| 500 | 2.0 | VROC (Microfluidic) |

| 1000 | 2.0 | Capillary Viscometer |

| 5000 | 2.0 | Capillary Viscometer |

Table 2: Power-Law Parameters for Different Non-Newtonian Fluids

| Fluid Type | Consistency Index (m) | Flow Behavior Index (n) | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shear-Thinning Polymer Solution | 0.5 - 5.0 Pa·sⁿ | 0.3 - 0.7 | Fermentation broths, cosmetic gels [24] |

| Shear-Thickening Suspension | 1.0 - 10.0 Pa·sⁿ | 1.2 - 1.8 | Cornstarch-water mixtures [21] |

| Bingham Plastic (Mayonnaise) | Yield Stress: 50 - 100 Pa | ~1 (after yield) | Food products, drilling muds [21] |

Workflow Visualization

Experimental Workflow for Rheology

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Rheological Studies

| Item | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Standard Newtonian Fluids | Calibration and validation of viscometers. These fluids (e.g., certified viscosity oils, sucrose solutions) have a constant viscosity independent of shear rate, providing a known baseline [22]. |

| Power-Law Model Fluids | Used as non-Newtonian reference materials. Aqueous solutions of polymers like xanthan gum (shear-thinning) or cornstarch suspensions (shear-thickening) help validate rheometer performance for non-Newtonian analysis [21]. |

| Rotational Rheometer | The primary instrument for comprehensive rheological characterization. It applies controlled shear stress or shear rate to a sample and measures the response, ideal for determining flow curves and viscoelastic properties [22]. |

| Microfluidic Viscometer (VROC) | Provides absolute viscosity measurements with very small sample volumes (≤100 µL). Excellent for characterizing precious or hard-to-synthesize fluids, such as concentrated biopharmaceutical products, over a wide shear rate range [22]. |

| Capillary Viscometer | Measures viscosity by timing the flow of a fluid through a narrow tube. Well-suited for high-shear-rate testing, simulating conditions like pumping or filtration, based on the Hagen-Poiseuille law [22]. |

Advanced Tools and Techniques for Scale-Up Implementation

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) for Predicting Hydrodynamic Behavior

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is predicting hydrodynamic behavior so critical for chemical process scale-up?

The performance of a chemical process is governed by the complex interplay between reaction kinetics (the chemical reaction itself) and transport phenomena (the movement of mass, heat, and momentum) [13]. While a lab-scale reactor may exhibit excellent yields, simply enlarging its dimensions does not guarantee equivalent performance. This is because hydrodynamic behavior is inherently scale-dependent; factors like diffusion times, turbulent eddies, and heat transfer rates change with reactor size [13]. Accurately predicting this behavior is essential to avoid costly scale-up failures.

Q2: What is the role of CFD in a modern, model-assisted scale-up strategy?

CFD is a powerful numerical tool for solving the fundamental equations of fluid flow, heat transfer, and mass transfer [13]. In a model-assisted scale-up approach, CFD is used to:

- Probe Hydrodynamics: Create a detailed, three-dimensional map of velocity, temperature, and phase fractions at both pilot and commercial scales [13].

- Inform Phenomenological Models: Provide critical data, such as residence time distribution, to tune faster, system-level models [13].

- Reduce Physical Testing: By identifying potential scale-up gaps computationally, this approach can significantly reduce the need for expensive and time-consuming pilot and demonstration plants [13].

Q3: In a catalytic process, what key transport phenomena can CFD help investigate?

CFD can assess both external and internal mass transport limitations.

- External Transport: For catalytic reactions, CFD can simulate the access of reactants to the catalyst particle surface. For instance, in viscous systems like polymer melt hydrogenolysis, CFD simulations have been used to identify stirring parameters that maximize the extension of the gas-melt interface and catalyst contact, directly impacting catalyst effectiveness [4].

- Internal Transport: While CFD typically models flow around particles, its results can inform analyses of intra-particle diffusion. For example, the ability of large polymer chains to penetrate catalyst pores can be a significant limitation, and understanding the external flow field is a first step in a multi-scale analysis [4].

Q4: My CFD simulation has converged, but how do I effectively analyze and interpret the results?

A structured workflow is key to practical CFD analysis [25]:

- Plan: Before loading results, decide which variables (e.g., velocity, species concentration) and which locations (e.g., near catalyst surfaces, at the reactor outlet) are most relevant to your research question.

- Visualize Qualitatively: Use contour plots, vector plots, and streamlines to get a spatial understanding of the flow and transport processes.

- Analyze Quantitatively: Extract numerical data by creating charts, tables, and reports for key parameters, such as the average shear rate in a mixing vessel or the mass flux across a specific boundary.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inaccurate Prediction of Mixing Efficiency in a Stirred Tank

- Symptoms: Poor agreement between simulated and experimental tracer concentration data; inability to predict dead zones or short-circuiting.

- Methodology: A simplified CFD approach for modeling mass transport in complex structures, like catalytic open-cell foams or stirred reactors, can be employed [26]. This involves creating a representative geometry of the system and solving for flow and species transport.

- Solution:

- Geometry & Mesh: Ensure the impeller and tank geometry are accurately represented. Use a sufficiently refined mesh, especially in the impeller region and near tank walls. For complex geometries, a dedicated meshing tool may be required.

- Turbulence Model: Select an appropriate turbulence model (e.g., k-ε, k-ω SST) that is validated for your specific flow regime and reactor geometry.

- Boundary Conditions: Accurately define the impeller motion using a Moving Reference Frame (MRF) or Sliding Mesh technique. Set appropriate boundary conditions for inlets and outlets.

- Validation: Always validate your mixing simulation against experimental data, such as Residence Time Distribution (RTD) curves.

Problem 2: Failure to Capture Mass Transport Limitations in a Catalytic Packed Bed Reactor

- Symptoms: The model over-predicts reaction conversion; simulated concentration profiles do not match experimental measurements along the reactor length.

- Methodology: Model mass transport in catalytic systems by simulating the flow and species transport through a representative unit cell of the packed bed or foam structure [26].

- Solution:

- Reaction Model: Incorporate a heterogeneous reaction model that accounts for the kinetics at the catalyst surface. A simple surface reaction may not be sufficient.

- Porous Media: If modeling the entire bed, define the catalyst zone as a porous medium with correct permeability and inertial loss coefficients. For detailed analysis, model the interstitial flow around individual catalyst particles.

- Mass Transfer Correlation: Verify that the local mass transfer coefficients between the bulk fluid and the catalyst surface are being calculated correctly. The model should resolve the concentration boundary layer.

Problem 3: High Viscosity Fluid Simulation Diverges or Yields Unrealistic Results

- Symptoms: Simulation fails to converge; computed velocities are abnormally high or low; excessive shear rates.

- Methodology: As demonstrated in studies of polyolefin recycling (polymer melts with viscosities ~1-1,000 Pa s), a careful setup is required for highly viscous, often non-Newtonian fluids [4].

- Solution:

- Material Properties: Accurately define the fluid's viscosity. For non-Newtonian fluids, use the correct model (e.g., Power Law, Carreau) and input rheological data obtained from experiments [4].

- Solver Settings: Use a pressure-based solver suited for incompressible flows. Employ robust, first-order discretization schemes for initial simulations and switch to higher-order schemes only after the solution has stabilized.

- Wall Treatment: Ensure the near-wall mesh and turbulence model are appropriate for the expected low Reynolds number (laminar) flow often associated with highly viscous fluids [4].

Quantitative Data for Polyolefin Hydrogenolysis System

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from a CFD-assisted study on catalytic polyolefin hydrogenolysis, a process with highly viscous fluids [4].

| Parameter | Description / Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Melt Viscosity (μ) | 1 - 1,000 Pa s (at relevant shear rates) [4] | 3 orders of magnitude higher than honey; dictates laminar flow regime. |

| Power Number (Np) | 15,000 - 40,000 (Optimum range identified) [4] | Dimensionless number to maximize catalyst effectiveness via stirring. |

| Characteristic Polymer Dimension (Λ) | ~22 nm (for HDPE, Mw=200 kDa) [4] | Predicts accessibility of polymer chains to catalyst pores (>6 nm). |

| Hatta Number | ~5 (Estimated for the system) [4] | Indicates that the reaction rate is about five times the diffusion rate of H2. |

Experimental Protocol: CFD-Guided Stirrer Optimization for a Catalytic Reaction

Objective: To identify optimal stirring parameters (rate, impeller type) that maximize catalyst effectiveness in a three-phase (gas-liquid-solid) reaction system with a viscous fluid.

Materials:

- Reactor System: Bench-scale stirred tank reactor with temperature and pressure control.

- CFD Software: A commercial or open-source CFD package (e.g., ANSYS Fluent, OpenFOAM).

- Data Acquisition: Equipment for online/offline product analysis (e.g., GC-MS).

Methodology:

- Rheological Characterization: Experimentally measure the viscosity of the reaction fluid as a function of shear rate and temperature to define accurate material properties for the CFD model [4].

- Base Case Simulation: Develop a CFD model of the reactor with a baseline stirrer configuration. Include the multiphase flow (e.g., Volume of Fluid method) and solve for flow and species transport.

- Parameter Variation: Run a series of simulations varying the stirring rate and/or impeller geometry. Monitor key outputs like the power number and the computed gas-liquid interfacial area.

- Experimental Validation: Run the reaction in the physical reactor at the parameters identified by CFD as optimal (e.g., within the power number range of 15,000-40,000) and at sub-optimal parameters for comparison [4].

- Model Calibration: Compare experimental results (e.g., conversion, product yield) with CFD predictions. Calibrate the model (e.g., reaction kinetics) to improve its predictive accuracy for future scale-up studies.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated model-assisted scale-up approach, combining experiments and different levels of modeling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Material Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their functions for conducting CFD-informed experimental studies in catalytic reactor design.

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Mechanical Stirrer | Provides the necessary torque to agitate highly viscous fluids (up to 10^5 Pa s) where magnetic stirrers fail (max ~1.5 Pa s) [4]. |

| Bench-Scale Reactor System | A multi-parallel, pressurized reactor system allows for high-throughput testing of catalyst and process parameters under controlled conditions [4]. |

| Rheometer | An instrument used to characterize the viscosity of non-Newtonian fluids (e.g., polymer melts) as a function of shear rate, providing critical input data for the CFD model [4]. |

| Porous Catalyst Particles | The solid catalyst, often with tailored pore size and volume, where the reaction takes place. Its effectiveness is limited by internal and external mass transport [4]. |

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Software | A physics-based modeling tool used to simulate and visualize 3D flow, heat transfer, and mass transfer phenomena at different scales, reducing empirical testing [13]. |

Phenomenological Modeling for System-Level Analysis and Scoping

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is a phenomenological model and how does it differ from a mechanistic one? A phenomenological model is a scientific construct that captures the empirical relationships between observable phenomena, focusing on descriptive accuracy and macroscopic behaviors derived from experimental data. Unlike mechanistic models, which are derived from fundamental first principles and detailed microscopic explanations, phenomenological models prioritize practical predictions and often use adjustable parameters fitted to observations without resolving underlying causal mechanisms. [27] In the context of catalyst scale-up, they are reduced-order, fundamentals-based models that use simplifying assumptions about geometry and flow fields to enable rapid process scoping. [13]

2. When should I use a phenomenological model during catalyst scale-up? Phenomenological modeling is particularly valuable during the early stages of process scoping and design. Its simplicity and computational speed make it suitable for exploring a wide range of operating conditions, performing parametric studies, and generating initial design concepts before committing to more resource-intensive simulations or pilot plant testing. [13] It serves as an efficient tool for synthesizing data across different studies and generating initial hypotheses about system behavior. [28] [29]

3. What are the common pitfalls in developing a phenomenological model? Common pitfalls include oversimplification that ignores critical phenomena, reliance on empirical fitting which can hinder extrapolation to untested regimes, and the inability to provide deep causal insights. A model is not "fit-for-purpose" if it fails to define its context of use, lacks data of sufficient quality or quantity, or has unjustified complexity. Proper model verification, calibration, and validation are essential to avoid these issues. [30] [27]

4. How can I validate a phenomenological model for transport phenomena? Validation centers on predictive accuracy, where the model is assessed by its ability to forecast responses to unseen data. In catalyst scale-up, this often involves comparing model predictions against data from a pilot plant. Furthermore, a validated computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model can predict hydrodynamic behavior at different scales and provide data (e.g., residence time distribution) to inform and validate the simplified hydrodynamics within the phenomenological model. [13] [27]

5. Can phenomenological and mechanistic modeling be integrated? Yes, a powerful approach involves using more detailed simulations like Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) to probe local hydrodynamics and mass transfer, the results of which (e.g., a residence time distribution) can then be used to inform the simplified hydrodynamic relationships within a phenomenological model. This creates a multi-scale, model-assisted framework that leverages the strengths of both approaches. [13] [31]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Model Fails to Predict Performance Upon Scale-Up

Symptoms:

- Model predictions accurately match laboratory-scale data but deviate significantly at pilot or commercial scale.

- Key performance metrics (e.g., conversion, yield, catalyst effectiveness factor) are over- or under-estimated at larger scales.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate Capture of Transport Phenomena | Compare the relative time scales of reaction and diffusion (e.g., calculate the Thiele modulus for internal diffusion or the Hatta number for external mass transfer). [4] | Refine the model to incorporate fundamental criteria for mass/heat transfer. Use CFD simulations to quantify the reactor flow field and mixing times, then simplify these findings into correlations for your phenomenological model. [13] [4] |

| Improper Scaling Assumptions | Audit the model for assumptions that are scale-dependent, such as perfect mixing or uniform temperature. Check if the power input per unit volume is constant across scales. | Replace idealized assumptions (e.g., CSTR) with more robust ones (e.g., a series of CSTRs representing a residence time distribution). Incorporate scaling laws derived from dimensionless numbers (e.g., Reynolds, Power number). [13] [4] |

| Change in Flow Regime | Analyze the Reynolds number at both laboratory and target commercial scales. | Identify the flow regime (laminar, transitional, turbulent) at the commercial scale and ensure the phenomenological model's flow and mixing correlations are valid for that regime. [13] |

Problem 2: Model is Not "Fit-for-Purpose"

Symptoms:

- The model is too slow for the required scoping studies.

- The model is too simplistic and misses key trends.

- Model outputs do not directly address the key questions of interest (e.g., it predicts conversion but not selectivity).

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unclear Context of Use (COU) | Clearly define the Question of Interest (QOI) the model must answer. For example: "What is the approximate reactor volume needed to achieve 90% conversion?" vs. "What is the precise local temperature profile inside the catalyst pellet?" | Re-scope the model's objective to align precisely with the QOI. A phenomenological model is excellent for the first question but unsuitable for the second. [30] |

| Incorrect Level of Complexity | Evaluate if the model has unnecessary mechanistic detail for a scoping exercise, or conversely, if it lacks a key phenomenon critical for even a preliminary assessment. | For scoping: simplify. Use the Manifold Boundary Approximation Method (MBAM) to systematically reduce complex models to their essential parameters. [31] For critical omissions: introduce a minimally complex term to capture the missing phenomenon, parameterized from available data. |

| Poorly Characterized Input Data | Review the quality and origin of the parameters in the model. Are they from your specific catalyst system, or from literature analogs? | Invest in targeted experimental work to determine critical parameters under relevant conditions. For example, perform rheological measurements on the polymer melt to accurately define viscosity for mass transfer calculations. [4] |

Problem 3: Inability to Reconcile Model with Experimental Data

Symptoms:

- Unable to achieve a satisfactory fit between model predictions and experimental data, even with parameter adjustment.

- Best-fit parameters take on physically unrealistic or impossible values.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Presence of Unaccounted Mass Transport Limitations | Conduct an experiment to assess the impact of mixing intensity (e.g., vary stirring rate in a slurry reactor). If the reaction rate or selectivity changes significantly with mixing, external transport limitations are likely present. [4] | Explicitly incorporate mass transfer steps into the reaction model. For example, model the reaction rate as being dependent on the H₂ concentration at the catalyst surface, which is itself determined by dissolution and diffusion rates from the gas-melt interface. [4] |

| Incorrect Reaction Network or Pathway | Analyze product distribution (selectivity) for clues about the dominant pathway. A model that only accounts for the main reaction may fail if significant side reactions are present. | Revisit the proposed reaction mechanism based on experimental evidence. Expand the phenomenological model to include key side or consecutive reactions, even if their kinetics are approximated. |

| Model Structural Error | Test the model's ability to predict data from experiments it was not fitted to, especially those conducted at different operating conditions (e.g., temperature, pressure). | If the structure is fundamentally wrong (e.g., assuming a zero-order reaction when it is first-order), no parameter adjustment will work. Return to experimental data to infer the correct functional form of the rate equations. |

Experimental Protocols for Model Development and Validation

Protocol 1: Quantifying Catalyst Effectiveness in a Slurry Reactor

Objective: To experimentally measure the catalyst effectiveness factor and diagnose external mass transport limitations for input into a phenomenological model.

Materials:

- High-pressure reactor with mechanical stirring capability

- Catalyst sample (e.g., Ru/TiO₂) [4]

- Polymer feedstock (e.g., High-Density Polyethylene, HDPE200) [4]

- High-purity hydrogen gas

- Gas Chromatograph (GC) or similar for product analysis

Methodology:

- Reactor Setup: Charge the reactor with a known mass of polymer and catalyst. Seal and purge the system with an inert gas before introducing H₂ to the desired reaction pressure. [4]

- Mixing Intensity Variation: Conduct a series of experiments at a constant temperature, pressure, and catalyst loading, but systematically vary the mechanical stirring rate (e.g., 50, 100, 200, 400 RPM).

- Reaction Monitoring: Heat the reactor to the target temperature (e.g., 498 K) and maintain for the specified reaction time. Monitor pressure drop or sample the gas/liquid phase periodically for product analysis. [4]

- Data Analysis:

- Plot key performance metrics (e.g., conversion, yield to desired products) against the stirring rate.

- If performance increases with higher stirring rates and then plateaus, the point of plateau indicates the minimization of external mass transfer limitations. The performance at this point can be considered the intrinsic kinetic regime.

- The catalyst effectiveness factor (η) can be quantified as the observed rate at a given stirring rate divided by the observed rate in the intrinsic kinetic regime. This data is directly used to parameterize the phenomenological model.

Protocol 2: Determining Regime of Internal Mass Transport Limitations

Objective: To assess whether polymer chains or reactants can access the interior pore structure of the catalyst.

Materials:

- Porous catalyst particles

- Solvents for physisorption analysis (e.g., N₂)

- Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) for polymer molecular weight analysis

- Rheometer

Methodology:

- Pore Structure Characterization: Use physisorption (e.g., BET method) to determine the catalyst's specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution. [4]

- Polymer Chain Dimension Estimation: Use the Freely Jointed Chain model to estimate the typical folded chain dimension (Λ) for your polymer feedstock. For HDPE with Mw = 200 kDa, Λ is approximately 22 nm. [4]

- Comparative Analysis: Compare the average catalyst pore diameter to the polymer's Λ.

- If the pore diameter is significantly smaller than Λ, internal mass transport limitations are severe, and the polymer cannot penetrate the pores. The reaction is confined to the external surface of the catalyst particle.

- This information must be built into the phenomenological model, for example, by basing the reaction rate on the external surface area of the catalyst rather than the total (internal + external) surface area.

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Diagram: Model-Assisted Scale-Up Workflow

Diagram: Transport & Kinetics in Catalyst Recycling

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Field of Study: Catalytic Hydrogenolysis of Polyolefins

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Mechanical Stirrer | Essential for agitating highly viscous polymer melts (μ ≥ 10 Pa s). Magnetic stirrers are unsuitable for high-molecular-weight polyolefins. [4] |

| Ru/TiO₂ Catalyst | A state-of-the-art catalyst for polyolefin hydrogenolysis. Provides a benchmark system for testing reactor and model performance. [4] |

| Commercial-Grade HDPE/PP | Representative, high-molecular-weight (Mw > 100 kDa) polymer feedstocks from consumer goods, ensuring industrial relevance of the research. [4] |

| Rheometer | Characterizes the non-Newtonian flow behavior of polymer melts, measuring viscosity as a function of shear rate and temperature. Critical for accurate mass transport calculations. [4] |

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Software | Models complex 3D hydrodynamics, shear rates, and phase interfaces in the reactor. Informs the development of simplified correlations for the phenomenological model. [13] [4] |

| Power Number (Np) Criterion | A dimensionless number identified as a key scaling parameter (Np = 15,000–40,000) to maximize catalyst effectiveness in viscous polymer melt systems. [4] |

Integrating Pilot Plant Data with Simulation Models

Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: Why is there a significant discrepancy between my pilot plant data and simulation model predictions, even with accurate kinetic parameters?

This commonly stems from unaccounted transport phenomena rather than chemical kinetics. In catalyst scale-up, the shift from ideal laboratory mixing to large-scale operations introduces mass and heat transfer limitations that dramatically impact catalyst effectiveness. [6] [4]

Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Assess External Mass Transfer: Calculate the Power number (Np) for your pilot reactor. For highly viscous systems like polymer melts, research indicates maintaining Np between 15,000–40,000 maximizes the catalyst effectiveness factor by ensuring adequate gas-liquid interfacial area and catalyst wetting. [4]

- Evaluate Mixing Efficiency: Confirm your impeller type and stirring rate are suitable for the fluid properties. Magnetic stirrers are ineffective for viscosities above ~1.5 Pa·s, necessitating mechanical stirring for systems like polyolefin melts (viscosities of 1–1,000 Pa·s). [4]

- Verify Data Collection Methodology: Ensure you are not making multiple changes simultaneously. Document every adjustment, valve position, and operating condition meticulously to avoid confusion during analysis. [32]

Q2: My catalyst performance is inconsistent between batches in the pilot plant. What could be causing this?

Batch-to-batch inconsistency often points to issues with reproducibility in mixing, heat management, or catalyst handling. [6]

Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Profile Temperature Distribution: Identify and measure for hotspots using thermocouples at multiple locations within the catalyst bed or reactor. These local temperature variations, often negligible at lab scale, can significantly alter selectivity and conversion rates at pilot scale. [6] [4]