Operando Characterization Techniques: Unlocking Dynamic Catalyst Behavior for Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advances and best practices in operando characterization techniques for catalyst analysis.

Operando Characterization Techniques: Unlocking Dynamic Catalyst Behavior for Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advances and best practices in operando characterization techniques for catalyst analysis. Tailored for researchers and scientists, it explores the fundamental principles distinguishing operando from in-situ methods, details the application of cutting-edge spectroscopic and microscopic tools, and addresses critical challenges in experimental design and data interpretation. By synthesizing insights from foundational concepts to troubleshooting and multi-technique validation, this review serves as an essential guide for elucidating dynamic structure-activity relationships in catalysts under working conditions, ultimately accelerating the development of next-generation catalytic systems for energy and biomedical applications.

Understanding Operando Characterization: Fundamental Concepts and Technical Significance

In the pursuit of sustainable energy solutions, understanding catalyst behavior under real-world operating conditions is paramount. Traditional ex situ characterization methods, which analyze materials before or after operation, provide valuable but fundamentally limited snapshots, as they miss the dynamic transformations occurring during catalytic processes [1]. The scientific community has therefore shifted towards advanced techniques that probe materials during experimentation, giving rise to the critical concepts of in situ and operando characterization. Within catalyst analysis research, particularly for applications like electrochemical CO₂ reduction (eCO₂RR), distinguishing between these two terms is not merely semantic but represents an epistemological shift towards functional realism [1]. This document delineates the critical distinctions between in situ and operando methodologies, providing structured protocols and application notes to guide researchers in the rigorous design and interpretation of experiments that capture catalyst structure-performance relationships under working conditions.

Terminological Foundations: In Situ vs. Operando

Core Definitions and Conceptual Evolution

The terms in situ and operando are often used interchangeably in literature, leading to ambiguity; however, formal definitions establish a clear hierarchical relationship where operando is a specific, demanding subset of in situ techniques [1] [2].

- In Situ Characterization: This approach involves performing measurements on a catalytic system while it is subjected to simulated reaction conditions (e.g., elevated temperature, applied voltage, or presence of reactants) [2]. The key differentiator is that the catalyst is in a relevant environment, but its catalytic activity is not necessarily being measured simultaneously. An example is heating a catalyst sample within an X-ray diffractometer to study its thermal stability without monitoring a catalytic reaction in real-time [1].

- Operando Characterization: This methodology represents a more advanced paradigm. It involves probing the catalyst under conditions that mimic a real-world operational environment while simultaneously measuring its catalytic activity/performance in real-time [2]. The term itself is derived from Latin, meaning "in the act of working" or "during operation" [1]. The quintessential goal is to make direct structure-function correlations under working conditions [3]. For instance, using X-ray absorption spectroscopy on a catalyst bed while it is actively converting CO₂ and quantifying the product formation rates with an integrated mass spectrometer would constitute an operando experiment [4].

Critical Distinction: The Simultaneous Performance Measurement

The defining boundary between in situ and operando studies is the simultaneous assessment of catalytic performance. As summarized in the table below, operando characterization explicitly links structural or electronic data with performance metrics.

Table 1: Core Conceptual Distinctions Between Ex Situ, In Situ, and Operando Characterization

| Aspect | Ex Situ | In Situ | Operando |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis Environment | Idealized, static (e.g., glovebox, bench-top) | Simulated reaction environment | Realistic, working device or reactor environment |

| Catalyst State | Pre- or post-operation | Under relevant conditions (T, P, environment) | During active operation and catalysis |

| Performance Data | Not measured during characterization | Not necessarily measured simultaneously | Measured simultaneously (e.g., current, product yield) |

| Primary Objective | Post-mortem analysis; initial structure | Structural/chemical evolution under conditions | Direct structure-activity-property relationships |

This distinction is critical because the catalyst's structure under operating conditions often differs significantly from its static state. For example, a study on copper-based catalysts for CO₂ reduction revealed that under operating potentials, the catalyst surface dynamically reconstructs, a state invisible to ex situ analysis [2].

Linguistic and Grammatical Usage

A common point of confusion in the literature is the phrasing "in operando." From a linguistic standpoint, the correct usage is "operando" without the preceding "in" [5]. The word "operando" is a Latin gerund (ablative case) that translates directly to "by working" or "while operating." Therefore, similar to terms like "operando spectroscopy," the standalone "operando" is grammatically correct, whereas "in operando" is considered redundant and an artifact of its juxtaposition with the established phrase "in situ" [5].

Experimental Protocols for Operando Catalyst Studies

Implementing a valid operando study requires meticulous design to ensure the collected data is both chemically significant and representative of true operating conditions.

Protocol 1: Baseline Operando Reactor Design and Setup

This protocol outlines the foundational steps for designing a reactor suitable for operando measurements, using an electrochemical flow cell for CO₂ reduction as a primary example.

1. Define Operational Conditions: - Objective: Establish the target operational parameters that the reactor must maintain. - Steps: - Determine the target current density (e.g., >100 mA/cm² for industrially relevant CO₂RR). - Define the electrolyte composition, flow rate, and temperature. - Specify the applied potential window and counter/reference electrode configuration. - Validation: The set parameters should match, as closely as possible, those used in benchmark performance testing outside the characterization tool [2].

2. Integrate Characterization Probe: - Objective: Design the reactor to allow a specific probe (e.g., X-ray beam, light source) to interact with the catalyst. - Steps: - Incorporate X-ray transparent windows (e.g., Kapton film, diamond) for X-ray-based techniques. - Use optical-grade windows (e.g., CaF₂ for IR, quartz for Raman) for spectroscopic techniques. - Precisely align the window and catalyst layer to ensure an unobstructed path and optimal signal. - Critical Consideration: Minimize the path length of the probe through the electrolyte or other cell components to reduce signal attenuation [2].

3. Integrate Performance Monitoring: - Objective: Incorporate tools for real-time activity measurement. - Steps: - Use an electrochemical potentiostat to apply potential and record current. - Integrate product analysis, such as online gas chromatography (GC) for gaseous products or liquid chromatography (LC) for liquid products. - For rapid detection of intermediates, employ differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS), where the catalyst is deposited directly onto a pervaporation membrane to minimize response time [2].

4. Mitigate Mass Transport Discrepancies: - Objective: Ensure reactor geometry and flow conditions do not artificially alter the catalyst's microenvironment. - Steps: - Avoid simple batch cells for reactions limited by gas diffusion. Instead, use gas diffusion electrodes (GDEs) in flow cells. - Design flow fields to ensure uniform electrolyte and reactant supply across the catalyst surface. - Pitfall Alert: Planar electrodes in batch cells can create large pH gradients and reactant depletion zones, leading to misinterpretation of intrinsic reaction kinetics [2].

Protocol 2: Multi-Technique Operando Data Acquisition and Correlation

The most powerful operando studies combine multiple techniques to gain a holistic view of the catalyst. This protocol describes the coupling of X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS) with electrochemical measurement.

1. Pre-Experiment Calibration and Alignment: - Objective: Ensure all systems are synchronized and calibrated. - Steps: - Calibrate the XAS energy scale using a standard foil (e.g., Cu foil for the K-edge). - Align the X-ray beam spot size to fully illuminate the electroactive catalyst area. - Synchronize the clocks of the potentiostat and the XAS data acquisition system.

2. Simultaneous Data Acquisition: - Objective: Collect structural and performance data concurrently. - Steps: - Begin electrochemical operation (e.g., apply a constant potential or initiate a linear sweep voltammogram). - Simultaneously initiate XAS data collection in quick-scanning or fluorescence mode. - Record electrochemical data (current, charge) and product stream data (from GC) with time stamps. - Key Parameter: The time resolution of the XAS measurement must be faster than the rate of the structural changes being investigated.

3. Data Correlation and Analysis: - Objective: Create direct structure-function relationships. - Steps: - Extract XAS-derived parameters (e.g., oxidation state from edge position, coordination number from EXAFS fitting) as a function of time or applied potential. - Plot these structural parameters directly against the simultaneously measured current density or product formation rate. - Example Insight: A sudden shift in oxidation state coinciding with a peak in ethylene production provides direct mechanistic evidence [4] [6].

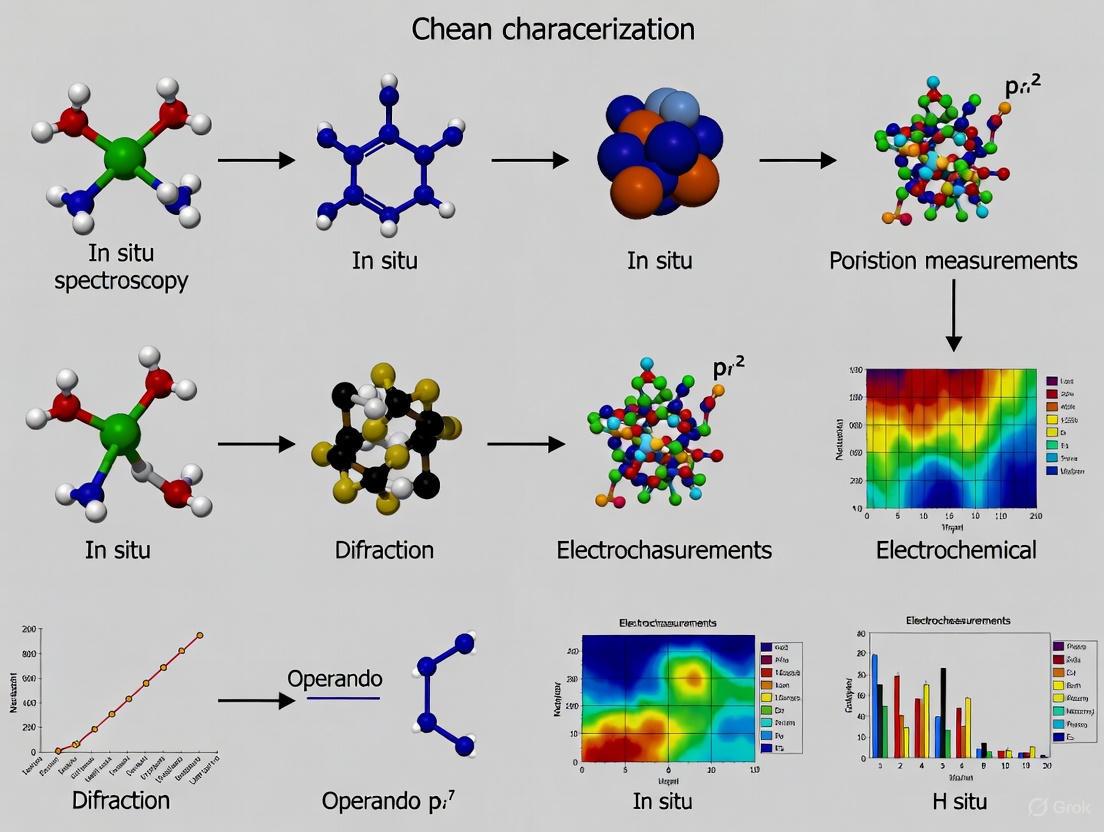

The logical workflow for establishing a rigorous operando study, from design to data interpretation, is summarized in the following diagram:

Figure 1: Logical workflow for designing and executing an operando characterization study.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful operando experimentation relies on specialized materials and reactor components that balance operational requirements with analytical capabilities.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Operando Catalyst Studies

| Item | Function & Application | Critical Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Gas Diffusion Electrode (GDE) | Provides a three-phase boundary for high-current-density gas-fed reactions (e.g., CO₂RR, O₂ Reduction). | Hydrophobic/hydrophilic balance; catalyst coating uniformity; mechanical stability under flow. |

| X-ray Transparent Window (e.g., Kapton, Diamond) | Allows penetration of the X-ray beam into the operating reactor for techniques like XRD and XAS. | Low X-ray absorption; chemical inertness; gas/liquid impermeability; pressure tolerance. |

| Optical Window (e.g., CaF₂, Quartz) | Serves as an optical port for vibrational spectroscopy (IR, Raman) within electrochemical cells. | High transmission in relevant IR/Raman range; minimal background signal; electrochemical inertness. |

| Ionomer/Catalyst Ink | Binds catalyst particles and facilitates ion transport within the catalyst layer. | Chemical compatibility; proton/hydroxide conductivity; minimal product selectivity impact. |

| Isotope-Labeled Reactant (e.g., ¹³CO₂, D₂O) | Traces reaction pathways and identifies the origin of products during operando spectroscopy. | High isotopic enrichment; chemical purity. |

| Pervaporation Membrane (for DEMS) | Separates the reactor from the mass spectrometer vacuum, allowing real-time detection of volatile intermediates/products. | Selective permeability to analytes of interest; low electrical resistance; catalyst adhesion. |

Data Presentation and Technique Selection

The selection of operando techniques is guided by the specific scientific question, as each method probes different aspects of the catalyst and its environment.

Table 3: Quantitative Overview of Common Operando Characterization Techniques

| Technique | Probed Information | Spatial Resolution | Time Resolution | Key Application in Catalysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operando XAS | Oxidation state, local coordination | ~μm (beam size) | Milliseconds-Seconds | Tracking dynamic changes in single-atom catalysts [4] |

| Operando XRD | Crystalline phase, lattice parameter | ~μm (beam size) | Seconds-Minutes | Identifying phase transitions in battery/electrode materials [1] |

| Operando Raman | Molecular vibrations, surface species | ~μm (laser spot) | Seconds | Detecting reaction intermediates on catalyst surfaces [2] |

| Operando IR | Surface functional groups, gas species | ~10s of μm | Milliseconds-Seconds | Monitoring electrolyte decomposition [1] |

| Operando DEMS | Volatile reaction intermediates/products | N/A (bulk measurement) | <1 Second | Identifying short-lived species in CO₂RR [2] |

The relationships between different characterization techniques and the specific catalyst properties they probe can be visualized as a hierarchical map, guiding researchers in selecting the appropriate tool for their investigation.

Figure 2: A technique selection map for operando characterization, linking common research questions to the most appropriate analytical methods.

The Critical Need for Real-Time Analysis in Catalyst Development

The relentless pursuit of sustainable chemical processes and clean energy technologies has placed catalyst innovation at the forefront of scientific research. Traditional catalyst characterization methods, which rely on pre- and post-reaction analysis (ex-situ), provide limited insights as they fail to capture the dynamic structural and chemical transformations catalysts undergo during operation. This critical gap has propelled the adoption of in-situ and operando characterization techniques—powerful methodologies that probe catalysts under simulated and actual working conditions, respectively [2]. While in-situ techniques are performed under simulated reaction conditions (e.g., elevated temperature, applied voltage), operando techniques go a step further by simultaneously measuring catalyst activity while characterizing its structure, thereby providing a direct link between structure and function [2].

The paradigm shift towards real-time analysis is driven by the urgent need to elucidate reaction mechanisms and establish concrete links between a catalyst's physical/electronic structure and its activity, selectivity, and stability [2] [4]. This understanding is paramount for the rational design of next-generation catalytic systems, which are essential for achieving United Nations Sustainable Development Goals related to affordable and clean energy, responsible consumption and production, and climate action [2]. This Application Note details the fundamental principles, experimental protocols, and practical implementation of key operando techniques, providing a structured framework for researchers to integrate these powerful methods into their catalyst development workflows.

Foundational Techniques and Protocols

This section outlines the core operando methodologies, including their underlying principles, standard operational procedures, and the specific insights they provide into catalytic systems.

Operando X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS)

- Principle and Application: Operando XAS is a cornerstone technique for elucidating the local electronic and geometric structure of catalytic active sites, including oxidation state, coordination chemistry, and bond distances [2] [4]. It is particularly powerful for studying non-crystalline materials and has become the backbone for investigating the stability and activity of advanced systems like Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs) during energy conversion processes such as electrochemical CO₂ reduction (eCO₂RR) [4].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Cell Design: Utilize an electro-chemical cell with X-ray transparent windows (e.g., Kapton film). For relevant conditions, modify zero-gap reactors with beam-transparent windows to minimize mass transport discrepancies [2].

- Sample Preparation: Deposit a uniform layer of the catalyst powder onto a conductive substrate like carbon paper or a gas diffusion layer. The loading should be optimized to achieve an appropriate edge jump while avoiding excessive absorption.

- Data Collection: Align the cell in the X-ray beam and acquire spectra in either fluorescence or transmission mode. Simultaneously apply the desired potential/current and record electrochemical data (e.g., current density, product distribution).

- Data Processing and Analysis: Pre-process the data (energy calibration, background subtraction, normalization) using software like Athena. Extract structural parameters (coordination numbers, bond distances, disorder) via EXAFS fitting in tools like Artemis.

Operando Vibrational Spectroscopy (IR and Raman)

- Principle and Application: Infrared (IR) and Raman spectroscopy are sensitive to molecular vibrations, making them ideal for identifying reaction intermediates and products adsorbed on catalyst surfaces or present in the reaction environment [2] [7]. Polarization-Modulation IR Reflection Absorption Spectroscopy (PM-IRAS) has been successfully employed to study SACs under reaction conditions [4].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Cell Design: Use a cell with an IR-transparent window (e.g., CaF₂, ZnSe) for IR spectroscopy, or a standard electrochemical cell with a quartz window for Raman. The working electrode should be a reflective disk (for IR) or the catalyst coated on a substrate.

- Control Experiments: Always perform control experiments without the reactant or catalyst to distinguish relevant signals from those of the support, solvent, or ambient atmosphere [2].

- In-situ Reaction Monitoring: Collect spectra at a series of applied potentials or temperatures while simultaneously tracking reaction rates. For mechanistic studies, isotope labeling (e.g., using ¹³CO₂) is a powerful complementary experiment to confirm the identity of intermediates [2].

- Data Interpretation: Correlate the appearance and disappearance of spectral bands with applied potential and reaction products to propose surface processes and reaction pathways.

Differential Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry (DEMS)

- Principle and Application: DEMS couples an electrochemical half-cell with a mass spectrometer, enabling the online, quantitative detection of volatile reaction products and intermediates [2]. This is crucial for determining product selectivity and identifying transient species.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Cell Assembly and Calibration: A key best practice is to minimize the path length between the catalyst surface and the mass spectrometer. This can be achieved by depositing the catalyst directly onto the pervaporation membrane of the DEMS cell, which drastically improves response time and sensitivity for detecting intermediates like acetaldehyde [2].

- Product Detection and Quantification: While applying potential, monitor the mass signals (m/z) corresponding to expected products and reactants. Use calibration procedures to relate ion current to quantitative reaction rates or Faradaic efficiencies.

- Kinetic Analysis: By tracking the formation rates of different products as a function of potential, insights into the reaction network and selectivity-determining steps can be obtained.

Reactor Design for Operando Analysis

A critical, often-overlooked aspect of operando studies is reactor design. The design must satisfy two key, and sometimes conflicting, requirements: it must be compatible with the analytical technique (e.g., have optical or X-ray transparent windows), and it must mimic the catalyst's environment in a real-world ("benchmarking") reactor as closely as possible [2]. Poor reactor design can introduce significant artifacts:

- Mass Transport Discrepancies: Many operando reactors are batch systems with planar electrodes, which suffer from poor reactant transport and the development of pH gradients. This creates a different microenvironment compared to flow cells or gas diffusion electrodes, potentially leading to misinterpretation of mechanistic data [2].

- Response Time and Signal-to-Noise: Sub-optimal design can increase the residence time of species, obscuring short-lived intermediates. It can also attenuate the analytical signal, leading to long acquisition times and poor data quality [2].

Best Practice: Co-design the electrochemical reactor and the operando cell to bridge the gap between characterization and real-world conditions. For techniques like DEMS and Grazing-Incidence XRD (GIXRD), careful optimization of the path length between the reaction event and the probe is essential for rapid and precise data collection [2].

Table 1: Key Operando Characterization Techniques and Their Applications.

| Technique | Key Applications | Probed Catalyst Properties | Example Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS) [2] [4] | Structure-activity relationships, active site evolution | Local electronic structure, oxidation state, coordination number, bond distance | Single-atom catalysts (SACs) for CO₂ reduction [4] |

| Vibrational Spectroscopy (IR, Raman) [2] [7] | Identification of reaction intermediates and surface species | Molecular vibrations, surface adsorption, reaction pathways | CO₂ reduction, hydrocarbon oxidation |

| Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry (ECMS/DEMS) [2] | Online product detection, reaction pathway deconvolution | Identity and quantity of volatile products/intermediates | CO₂ reduction to multi-carbon products [2] |

| Near-Ambient Pressure XPS (NAP-XPS) [4] | Surface composition and chemistry under reactive gases | Elemental composition, chemical states, adsorbates | Model catalysts, surface oxidation studies |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful execution of operando studies relies on a suite of specialized materials and instruments. The table below details key solutions and their functions in the context of catalyst research and development.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Operando Catalyst Studies.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function and Application in Catalysis |

|---|---|

| Catalyst Precursors (e.g., Metal salts, complexes) | Synthesis of heterogeneous catalysts, including supported nanoparticles and Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs) [4]. |

| High-Surface-Area Supports (e.g., Carbon black, TiO₂, Al₂O₃) | Dispersion of active metal phases, stabilization of SACs, and enhancement of electrical conductivity [4]. |

| Ion-Exchange Membranes (e.g., Nafion) | Serve as a proton-conducting electrolyte in electrochemical cells and as a separator in zero-gap reactor configurations [2]. |

| Isotope-Labeled Reactants (e.g., ¹³CO₂, D₂O) | Act as mechanistic probes in spectroscopic studies (e.g., IR, Raman) to track reaction pathways and confirm intermediate identity [2]. |

| Electrolyte Solutions (e.g., Aqueous KHCO₃, organic electrolytes) | Provide the ionic medium for electrochemical reactions, with pH and composition influencing activity and selectivity. |

| X-ray Transparent Windows (e.g., Kapton, Si₃N₄) | Enable the penetration of X-rays in operando XAS and XRD experiments while withstanding reaction environments [2]. |

Data Presentation and Quantitative Insights

Translating raw operando data into actionable knowledge requires rigorous data processing, cross-correlation between techniques, and quantitative analysis of catalytic performance. The following table synthesizes key performance metrics and structural information that can be derived from a multi-technique operando study.

Table 3: Correlating Operando Characterization Data with Catalytic Performance Metrics.

| Analytical Measurement | Data Output | Link to Catalyst Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Operando XAS | Oxidation state shift, changes in coordination number | Correlation with activation/deactivation phases; links electronic structure to turnover frequency (TOF). |

| Operando IR/Raman | Emergence/disappearance of spectral bands | Identification of key reaction intermediates linked to high selectivity pathways. |

| Operando DEMS/EC-MS | Faradaic efficiency (FE%) for products, rate of formation | Direct quantification of catalyst selectivity and stability under working conditions. |

| Electrochemical Kinetics | Tafel slope, apparent activation energy | Insight into the rate-determining step and mechanism, guided by structural data from spectroscopy. |

Advanced Applications and Future Outlook

The integration of operando characterization with automation and artificial intelligence is poised to revolutionize catalyst development. Data-rich experiments (DRE), facilitated by automated reaction platforms and real-time analytics, are generating the comprehensive, high-fidelity datasets needed to navigate the complexity of chemical synthesis [8]. These datasets, which capture full reaction kinetics rather than single time-point yields, are ideal for training machine learning (ML) and AI models. Such models can accelerate process optimization, classify reaction mechanisms from kinetic patterns, and even discover new synthetic pathways [8].

Furthermore, in-situ visualization microscopy techniques have made notable progress, enabling the imaging of ongoing catalytic reactions on SACs and revealing complex phenomena like facet-resolved catalytic ignition [4]. As these advanced data generation and interpretation methods mature, they will significantly shorten the development cycle for next-generation catalysts, paving the way for more sustainable chemical and energy technologies.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram summarizes the integrated, iterative workflow of modern catalyst development driven by operando characterization and data science.

Operando Catalyst Development Workflow: This diagram illustrates the iterative cycle of catalyst development, beginning with catalyst design and moving through operando experimental setup, real-time data acquisition, multi-modal data correlation, and the generation of mechanistic insights, which in turn inform the design of improved next-generation catalysts.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) is a highly versatile technique used to obtain high-resolution images and detailed surface information of samples, operating at a much greater resolution than optical microscopy [9]. The fundamental principle of SEM involves using a focused beam of high-energy electrons that is scanned across the surface of a specimen [10] [9]. The interactions between these electrons and the atoms within the sample generate various signals that carry different types of information about the sample's surface topography, composition, and other properties [10]. The resolution of SEM instruments can range from <1 nanometer up to several nanometers, making it an indispensable tool in fields ranging from materials science to catalyst research, particularly in the context of operando characterization for observing catalysts in their working states [4] [9].

For catalyst analysis, especially in emerging applications like electrochemical CO(_2) reduction reaction (eCO2RR) using single-atom catalysts (SACs), understanding these core technical principles is fundamental to interpreting data obtained under reaction conditions [4].

Fundamental Beam-Sample Interactions

When the primary electron beam hits the sample surface, it penetrates to a depth of a few microns, interacting with atoms in a region known as the interaction volume [9]. The extent of this volume depends on the accelerating voltage of the primary electrons and the density of the sample material [9]. These interactions produce a variety of signals, the most critical of which for imaging and analysis are secondary electrons, backscattered electrons, and characteristic X-rays [10] [11].

Table 1: Key Signals Generated from Electron-Beam Interactions

| Signal Type | Origin & Energy | Information Provided | Primary Application in Catalyst Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary Electrons (SE) | Inelastic scattering; emitted from surface atoms (<50 eV) [9]. | High-resolution topographic contrast [10] [9]. | Visualizing catalyst surface morphology, porosity, and nanostructure [11]. |

| Backscattered Electrons (BSE) | Elastic scattering from atomic nuclei; high energy [10] [9]. | Compositional (atomic number, Z) contrast; heavier elements appear brighter [10]. | Differentiating catalyst support from active metal particles or identifying elemental phases [11]. |

| Characteristic X-rays | Emission from electron relaxation within sample atoms [10]. | Elemental composition and concentration [10] [9]. | Quantitative elemental analysis of catalysts via Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) [11]. |

The following diagram illustrates the generation of these key signals from the interaction volume.

Signal Detection and Information Decoding

The signals generated from beam-sample interactions are captured by specialized detectors, each designed to optimize the collection of specific signal types.

- Secondary Electron Detection: The most common device is the Everhart-Thornley detector [10]. It consists of a scintillator inside a Faraday cage, which is positively charged to attract the low-energy SE [10]. The scintillator converts electrons into light, which is then amplified by a photomultiplier to produce a usable signal for image formation [10]. This detector is typically placed at an angle in the chamber to maximize detection efficiency [10].

- Backscattered Electron Detection: BSE detectors are typically solid-state detectors containing p-n junctions [10]. They work on the principle of generating electron-hole pairs when backscattered electrons are absorbed by the detector, thereby generating an electrical current proportional to the number of absorbed BSE [10]. These detectors are placed concentrically above the sample in a "doughnut" arrangement to maximize collection and often consist of symmetrically divided parts to enable both compositional and topographical contrast [10].

- X-ray Detection (EDS): Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) detectors capture the characteristic X-rays emitted from the sample [11]. The energy of each X-ray is measured, producing a spectrum where peaks correspond to specific elements, allowing for qualitative and quantitative elemental analysis and mapping [11].

Table 2: Detector Types and Their Functions in Analytical SEM

| Detector Type | Signal Detected | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Everhart-Thornley (E-T) | Secondary Electrons (SE) | High-resolution topographic imaging [10]. | Sensitive to surface details; requires charge dissipation on insulators [9]. |

| Solid-State BSE Detector | Backscattered Electrons (BSE) | Compositional (Z-contrast) and crystallographic imaging [10] [11]. | Contrast depends on atomic number; less surface-sensitive than SE [10]. |

| Energy-Dispersive X-ray (EDS) | Characteristic X-rays | Elemental identification, quantification, and mapping [9] [11]. | Spatial resolution limited by interaction volume (~1-3 µm); detection limits ~0.1-1 wt% [11]. |

The Scanning Electron Microscope Column and Beam Control

The electron column is the core assembly that generates, shapes, and directs the electron beam onto the sample. Electrons are emitted from a filament in the electron source (gun) and collimated into a beam [10]. This beam travels through the column, which consists of a set of electromagnetic lenses that focus and condense it [10] [9].

- Electron Sources: The source significantly influences SEM performance. Common types include: (1) Tungsten Filament: A cost-effective option with moderate resolution; (2) Lanthanum Hexaboride (LaB₆): Offers higher brightness and longer lifespan; and (3) Field Emission Gun (FEG): Provides the highest resolution due to its small probe size and is ideal for nanoscale catalyst analysis [11].

- Electromagnetic Lenses: These lenses, which can be electrostatic or magnetic, use electric or magnetic fields to focus the electron beam [10]. Condenser lenses regulate beam current and spot size, while the objective lens performs the final focusing onto the sample, determining working distance and resolution [9] [11].

- Scan Coils: Situated above the objective lens, these coils deflect the beam in a raster pattern across the X-Y plane of the sample surface, allowing for image formation pixel by pixel [9].

The entire column and sample chamber are maintained under a high vacuum to prevent electron scattering by gas molecules [9] [11].

Experimental Protocols for SEM Analysis in Catalyst Research

Protocol A: Basic High-Resolution Topographical Imaging

Objective: To acquire high-resolution images of catalyst surface morphology using Secondary Electrons.

- Sample Preparation: For non-conductive catalyst supports (e.g., alumina, silica), sputter-coat with a thin layer (5-15 nm) of gold or platinum to prevent charging [9] [11]. For conductive samples, mount securely on a SEM stub using conductive tape or epoxy.

- Instrument Setup: Insert sample into the chamber and establish high vacuum. Select a working distance of 5-10 mm. Set the accelerating voltage to a low or medium value (5-10 kV) to enhance surface sensitivity and minimize penetration [11].

- Beam Alignment: Align the electron beam and aperture to ensure optimal focus and current.

- Image Acquisition: Using the SE detector, navigate to the region of interest. Adjust the spot size and scan speed to optimize signal-to-noise. Fine-focus and correct for astigmatism at high magnification. Acquire the image.

Protocol B: Compositional Contrast and Phase Distribution Mapping

Objective: To identify and map different elemental phases within a catalyst material.

- Sample Preparation: Ensure a flat, polished surface is ideal for BSE imaging. Coating, if necessary, should be uniform and thin to avoid masking underlying composition.

- Instrument Setup: Use a higher accelerating voltage (15-20 kV) to enhance BSE yield. Ensure the BSE detector is active.

- Image Acquisition: Acquire a BSE image. Heavier elements (e.g., active metal particles) will appear brighter than the lighter catalyst support [10] [11].

- Elemental Verification: Perform EDS point analysis or area mapping on bright and dark regions to correlate brightness with elemental composition.

Protocol C: Operando-Capable SEM Considerations for Catalyst Studies

Objective: To adapt SEM principles for studying catalysts under reactive conditions, bridging to true operando characterization.

- Environmental SEM (ESEM) / Variable Pressure (VP-SEM): Utilize these specialized SEMs that allow for the presence of gas in the sample chamber. This enables imaging of insulating or hydrated samples without coating and provides a pathway for introducing reactive gases [9] [11].

- Correlative Analysis: Integrate SEM imaging with other techniques. For instance, combine high-resolution SEM with ex-situ X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) to correlate morphology with surface chemistry [11].

- Beam Parameter Control: Use lower accelerating voltages and beam currents to minimize electron-beam damage to sensitive catalyst materials, which is crucial for obtaining representative data [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials and Components for SEM Analysis in Catalyst Research

| Item / Component | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Conductive Mounting Stubs & Tape | Provides a stable, electrically grounded platform for mounting solid samples. |

| Sputter Coater (Au, Pt, C targets) | Applies an ultra-thin, conductive metal layer to non-conductive samples to prevent surface charging during imaging [9] [11]. |

| Conductive Silver Epoxy / Paint | Creates a highly conductive path between the sample and the stub, essential for reliable analysis. |

| Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) System | Integrated detector and software for elemental analysis, quantification, and mapping of catalyst compositions [9] [11]. |

| Field Emission Gun (FEG) Electron Source | Provides a high-brightness, coherent electron source for ultimate spatial resolution (<1 nm) required for nanoscale catalyst characterization [11]. |

| Backscattered Electron (BSE) Detector | Essential for obtaining atomic number (Z)-contrast images to distinguish between different elemental phases in a catalyst [10] [11]. |

| Cryo-Preparation Stage | Allows for the preparation and analysis of beam-sensitive or hydrated materials (e.g., certain catalyst precursors) by freezing them in a vitreous state. |

Historical Evolution and Emerging Capabilities in Dynamic Characterization

The rational design of high-performance catalysts is intrinsically linked to a fundamental understanding of their active sites and reaction mechanisms. For decades, catalyst characterization was dominated by ex-situ methods, which analyzed materials before or after reactions, providing a static and often incomplete picture. The dynamic structural and electronic changes that occur under operational conditions were largely inferred rather than directly observed. The advent of in-situ and operando characterization techniques has revolutionized this paradigm, enabling real-time observation of catalysts during reaction. In-situ techniques probe the catalyst under simulated reaction conditions, while operando (Latin for "working") methods combine this real-time observation with simultaneous measurement of catalytic activity and selectivity [12] [2]. This evolution towards dynamic characterization has been crucial for elucidating complex reaction mechanisms, identifying true active sites, and understanding catalyst degradation pathways, thereby accelerating the development of next-generation catalytic systems for energy conversion and sustainable chemical synthesis [12] [13].

Historical Evolution of Dynamic Characterization

The field of catalyst characterization has undergone a profound transformation, shifting from post-reaction analysis to real-time observation under working conditions.

The Paradigm Shift from Ex-Situ to Operando

Traditional ex-situ methods, while valuable, presented a significant limitation: catalysts often undergo dramatic changes when exposed to reaction environments (high temperature, pressure, electrochemical potential), meaning the pre- or post-reaction state may not reflect the active state. This led to misinterpretations, where spectator species were mistaken for active sites [12]. The growing recognition of this "materials gap" drove the development of in-situ cells and reactors that could accommodate realistic conditions inside characterization instruments. This evolved further into the operando philosophy, which rigorously links the structural data obtained spectroscopically or microscopically with quantitative activity data collected at the very same time [2] [14]. This paradigm shift has been essential for bridging the gap between model catalysts and real-world systems.

Key Technological Milestones

The historical evolution of dynamic characterization has been propelled by advancements in synchrotron radiation, probe microscopy, and mass spectrometry. The following table summarizes key technique developments and their impact on catalyst analysis.

Table 1: Key Technological Milestones in Dynamic Characterization

| Decade | Technological Advancement | Impact on Catalyst Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| 1980s-1990s | Early in-situ cells for XRD and IR spectroscopy | Enabled first glimpses of catalyst structure under controlled gas atmospheres and temperature. |

| 2000s | Proliferation of operando methodology; Synchrotron-based XAS | Established a rigorous framework connecting structure and activity; provided electronic and geometric structure of active sites under reaction. |

| 2010s-Present | High-spatial-resolution TEM/STEM; Ambient Pressure XPS (AP-XPS) | Directly imaged structural dynamics (e.g., particle migration, surface faceting) at atomic scale; probed surface chemistry in the presence of gases or liquids. |

| Present-Future | Multi-technique integration; Modulated Excitation Spectroscopy; Machine Learning | Deconvolutes complex reaction mechanisms; isolates active species from spectators; manages large datasets for pattern recognition [14]. |

Emerging Capabilities and Current State-of-the-Art

Modern operando characterization offers an unprecedented toolkit for probing catalysis, with techniques tailored to extract specific information about the catalyst's dynamic nature.

Advanced Probing Techniques and Their Applications

Current research leverages a suite of sophisticated techniques to build a holistic view of catalytic processes. Each technique provides a unique piece of the puzzle, from bulk structure to surface intermediates.

Table 2: Overview of Key Operando Characterization Techniques

| Technique | Information Provided | Application Example in Catalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Operando X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS) | Oxidation state, local coordination geometry, bond distances [15] [2]. | Tracking the dynamic evolution of single-atom catalysts (SACs) during electrochemical CO₂ reduction, identifying the reduction of metal centers [15]. |

| Operando X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | Crystalline phase, particle size, lattice parameters [12]. | Observing phase transformations in metal oxide OER catalysts, such as the formation of active (oxy)hydroxides from pristine oxides [12]. |

| Operando Vibrational Spectroscopy (IR, Raman) | Identity of surface-adsorbed reaction intermediates and poisons [2]. | Detecting *CO, *COOH, and other key intermediates during CO₂ electroreduction, helping to elucidate reaction pathways [2]. |

| Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry (EC-MS) | Identity and quantity of gaseous or volatile products in real-time [2]. | Coupling product detection with applied potential to determine Faradaic efficiency and probe reaction mechanism kinetics. |

| Near-Ambient Pressure XPS (NAP-XPS) | Surface elemental composition and chemical state in the presence of a reactant gas [15]. | Studying the surface of Cu-based catalysts during the CO₂ reduction reaction, revealing the role of subsurface oxygen [2]. |

Elucidating Complex Reaction Mechanisms

The application of these techniques has been instrumental in moving beyond oversimplified models. For instance, in the Oxygen Evolution Reaction (OER), operando studies have revealed multiple competing mechanisms, such as the Adsorbate Evolution Mechanism (AEM), Lattice Oxygen Mechanism (LOM), and Oxide Path Mechanism (OPM) [12]. Furthermore, a Cooperative Solid-Molecular Mechanism (SMM) has been identified on NiFe-based catalysts, where dissolved FeO₄²⁻ species act as molecular co-catalysts with the solid surface [12]. Such insights, which defy traditional paradigms, are only accessible through dynamic characterization.

Tracking the Dynamic Evolution of Active Sites

A paramount capability of operando techniques is tracking the often-reversible transformations of catalysts. For example, single-atom catalysts (SACs) can dynamically evolve into clusters or nanoparticles under reaction conditions, and vice versa [13]. Operando XAS and microscopy have been critical in correlating these structural dynamics with catalytic performance, revealing that the initial pre-catalyst is often not the true active species. This understanding is vital for designing catalysts with optimal stability and activity [15] [13].

Application Notes and Detailed Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing core operando characterization techniques, focusing on practical considerations for obtaining reliable and interpretable data.

Protocol 1: Operando X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy for Electrocatalysts

Application: This protocol is used to determine the electronic structure and local coordination environment of metal centers in an electrocatalyst (e.g., for OER or CO₂ reduction) under working conditions [15] [2].

Workflow Diagram:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Electrode Preparation:

- Synthesize the catalyst material (e.g., a single-atom M-N-C catalyst).

- Prepare a catalyst ink by dispersing the powder in a mixture of solvent (e.g., isopropanol/water), Nafion binder (e.g., 5 wt%), and optionally, a conductive additive.

- Deposit the ink onto a conductive, X-ray transparent substrate (e.g., carbon paper or a glassy carbon disk) to achieve a uniform thin film with a known catalyst loading (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mg/cm²).

Operando Electrochemical Cell Assembly:

- Use a custom or commercially available operando XAS flow cell with X-ray transparent windows (e.g., Kapton or polyimide film).

- Assemble a standard three-electrode configuration: the prepared working electrode, a reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) as the reference, and a Pt-mesh or wire as the counter electrode.

- Ensure the cell design allows for efficient electrolyte flow and bubble removal to minimize mass transport artifacts [2].

- Connect the cell to a potentiostat and an electrolyte reservoir.

Data Collection:

- Mount the cell in the X-ray beamline and align the beam to strike the catalyst layer through the window.

- Introduce the electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M KOH for OER or 0.5 M KHCO₃ for CO₂RR) and purge with inert gas or reactant (e.g., CO₂).

- Simultaneously apply a sequence of electrochemical potentials (e.g., from open-circuit voltage to reaction potentials) and collect XAS spectra at each potential, typically in fluorescence mode for dilute samples.

- Critical Control: Collect a spectrum of a metal foil reference simultaneously with the sample spectra for precise energy calibration.

Data Analysis:

- Process the raw data to extract XANES (X-ray Absorption Near Edge Structure) and EXAFS (Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure) regions.

- XANES Analysis: Analyze the absorption edge position and shape to determine the average oxidation state of the metal absorber.

- EXAFS Analysis: Fit the EXAFS oscillations to obtain quantitative structural parameters: coordination numbers, bond distances, and disorder factors for the shells of atoms surrounding the absorber.

Correlation with Performance:

Protocol 2: Differential Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry (DEMS)

Application: DEMS is used for the online identification and quantification of volatile or gaseous reaction intermediates and products during electrocatalysis, providing crucial mechanistic information [2].

Workflow Diagram:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Preparation of the Porous Working Electrode:

- The catalyst is deposited directly onto a porous, hydrophobic membrane (e.g., PTFE or GORE-SELECT) that is permeable to volatile species but impermeable to liquid electrolyte. This minimizes the path length between the catalyst site and the mass spectrometer, ensuring a fast response time [2].

DEMS Cell Assembly:

- The catalyst-coated membrane is pressed against the inlet system of the mass spectrometer to form a tight seal.

- The assembly is integrated into an electrochemical cell containing the electrolyte and counter/reference electrodes.

System Calibration:

- Before the experiment, the mass spectrometer must be calibrated for the species of interest (e.g., H₂, O₂, CO, C₂H₄). This involves introducing a known quantity of the gas and measuring the corresponding ion current signal.

Operando Measurement:

- The electrolyte is purged with an inert gas.

- An electrochemical technique (e.g., chronoamperometry or linear sweep voltammetry) is applied using the potentiostat.

- Simultaneously, the mass spectrometer continuously monitors selected ion currents (m/z ratios) corresponding to potential products.

Data Interpretation and Quantification:

- The Faradaic efficiency (FE) for a product is calculated using the equation: FE (%) = (z * F * Qₘ) / (Qₑ) * 100%, where

zis the number of electrons transferred to form one molecule of the product,Fis the Faraday constant,Qₘis the charge calculated from the calibrated mass signal, andQₑis the total electrochemical charge passed. - The temporal correlation between potential steps and the appearance of products can reveal kinetic information and reaction pathways.

- The Faradaic efficiency (FE) for a product is calculated using the equation: FE (%) = (z * F * Qₘ) / (Qₑ) * 100%, where

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Operando Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Critical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Transparent Windows (Kapton, Polyimide) | Allows X-rays to penetrate the operando reactor while sealing the electrochemical environment [2]. | Must be chemically inert, have consistent thickness, and withstand internal cell pressure. |

| Pervaporation Membranes (e.g., PTFE) | Used in DEMS to separate the electrolyte from the mass spectrometer vacuum while allowing gaseous products to pass [2]. | Hydrophobicity and pore size are critical for preventing electrolyte leakage and optimizing response time. |

| Isotope-Labeled Reactants (e.g., ¹⁸O₂, ¹³CO₂, D₂O) | Tracers for elucidating reaction mechanisms and the origin of atoms in products (e.g., O₂ from lattice oxygen vs. water) [12] [2]. | High isotopic purity is essential. Requires careful handling and specific safety protocols. |

| Custom Electrochemical Cells | Houses the catalyst and electrodes under controlled reaction conditions within the beamline or spectrometer. | Design must optimize for mass transport, electrode alignment, and signal-to-noise ratio for the specific technique [2]. |

| Stable Reference Electrodes (e.g., RHE) | Provides a stable and accurate potential reference for all electrochemical measurements. | Must be compatible with the electrolyte and reaction conditions to prevent drift or contamination. |

Common Pitfalls and Mitigation Strategies

Despite their power, operando techniques are susceptible to artifacts and misinterpretation. Key pitfalls and mitigation strategies include:

- Reactor Design Mismatch: In-situ reactors often have different mass transport characteristics (e.g., batch vs. flow) compared to benchmarking reactors, which can alter the catalyst's microenvironment and activity [2].

- Mitigation: Co-design reactors to more closely mimic benchmarking conditions, use thin-layer electrolyte configurations, and employ computational fluid dynamics to model transport [2].

- Beam-Induced Damage: High-flux X-ray or electron beams can locally heat the catalyst, reduce metal centers, or create radicals, thereby altering the very structure being studied [12].

- Mitigation: Use lower beam fluxes, defocus the beam, raster the beam across the sample, and perform control experiments to test for damage.

- Distinguishing Active from Spectator Species: Not all observed structural features or intermediates are catalytically relevant.

- Mitigation: Employ modulated excitation spectroscopy with phase-sensitive detection, which isolates signals from species that respond to a applied stimulus (e.g., potential, concentration) from the static background [14]. Correlate the kinetics of structural changes with activity metrics.

- Over-interpretation of Data: Extracting more information than the data or technique can reliably support is a common risk.

- Mitigation: Use a multi-technique approach to triangulate findings [14]. For example, combine XAS (electronic/geometric structure) with Raman spectroscopy (surface intermediates) to build a more robust mechanistic model.

Future Perspectives

The future of dynamic characterization lies in integration and intelligence. Key emerging trends include:

- Multi-Modal and Correlative Characterization: The simultaneous combination of multiple techniques (e.g., XAS + XRD + IR) in a single experiment is becoming more prevalent, providing a multi-faceted and concurrent view of catalytic mechanisms [14].

- Advanced Data Science and Machine Learning: The complex, high-volume datasets generated by operando studies are ideal for machine learning algorithms. These tools can identify subtle patterns, classify spectra, and help model complex structure-activity relationships that are not apparent through traditional analysis [2].

- Bridging the Pressure and Materials Gaps: Future innovations will focus on pushing operando techniques to higher pressures and more complex, real-world reactor geometries (e.g., zero-gap membrane electrode assemblies) to make mechanistic insights directly relevant to industrial application [2].

- Probing at Faster Time Scales: The development of techniques with ultra-fast time resolution (e.g., microsecond to millisecond) will allow for the direct observation of transient intermediates and the elementary steps of catalytic cycles.

Bridging the Gap Between Model Systems and Real-World Catalytic Environments

The transition from laboratory discovery to industrial application is a critical yet challenging journey in catalytic science. Often, catalysts that demonstrate exceptional performance under idealized, simplified laboratory conditions fail to maintain their activity, selectivity, and stability when deployed in real-world industrial environments. This performance gap stems from fundamental differences between well-controlled model systems and the complex, dynamic conditions of actual catalytic processes. Operando characterization techniques—methods that analyze catalysts under working conditions while simultaneously measuring activity—have emerged as powerful tools for bridging this divide [2]. By providing real-time insights into catalyst structure, active sites, and reaction intermediates during operation, these techniques enable researchers to understand and address the disparities between model and real-world systems, ultimately guiding the design of more robust and effective catalysts.

The core challenge lies in the simplified conditions typically employed in laboratory settings. Model systems often use pure reactants, absence of poisons, and idealized reactor configurations that differ substantially from industrial environments containing complex feedstocks, contaminants, and practical engineering constraints [2] [16]. For instance, studies comparing laboratory-aged and real-world aged Cu/SSZ-13 selective catalytic reduction (SCR) catalysts revealed that standard laboratory hydrothermal aging alone poorly mimics the properties of field-aged catalysts, particularly in critical performance metrics like high-temperature deNOx efficiency and NH₃ oxidation capacity [16]. This discrepancy underscores the necessity of developing more sophisticated aging protocols and characterization approaches that can accurately predict catalyst behavior in practical applications.

Experimental Protocols for Real-World Catalyst Assessment

Comparative Aging Study Protocol

Objective: To identify gaps between accelerated laboratory aging and real-world aging of commercial Cu/SSZ-13 catalysts through atomic-level characterization.

Materials and Equipment:

- Lab-degreened (DG), hydrothermally aged (HTA), hydrothermal+sulfur aged (HTA+SOx), and real-world aged (RWA) catalyst samples [16]

- X-ray diffractometer (XRD)

- H₂-temperature programmed reduction (TPR) system

- NH₃-temperature programmed desorption (TPD) apparatus

- Spectroscopic instruments (EPR, NMR)

- SCR reaction testing apparatus

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Obtain catalyst samples from both laboratory aging protocols and real-world deployments. Laboratory aging should include:

Textural Properties Analysis:

- Perform XRD analysis on gently crushed coated monolith samples via sieving

- Compare diffraction features with pure chabazite reference material

- Estimate relative crystallinity by comparing peak intensities [16]

Acidic Properties Assessment:

- Conduct NH₃-TPD measurements using approximately 100 mg catalyst samples

- Pre-treat samples in He at 500°C for 1 hour, then adsorb NH₃ at 100°C

- Perform TPD by heating from 100°C to 650°C at 10°C/min in flowing He [16]

SCR Kinetics Evaluation:

- Perform steady-state SCR reaction tests

- Measure NO conversion efficiencies across a temperature range (e.g., 150-550°C)

- Compare low-temperature and high-temperature deNOx efficiency between differently aged samples [16]

Spectroscopic Characterization:

- Utilize EPR and NMR spectroscopy to identify changes in Cu speciation

- Analyze framework integrity and detect amorphous phase formation [16]

Table 1: Key Characterization Techniques for Bridging the Model-Real World Gap

| Characterization Technique | Information Obtained | Relevance to Real-World Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | Crystallinity, phase changes, structural degradation | Detects support deterioration and amorphous phase formation in real-world aged catalysts [16] |

| NH₃-Temperature Programmed Desorption (TPD) | Acid site density, strength, and distribution | Reveals changes in acidic properties critical for SCR performance [16] |

| H₂-Temperature Programmed Reduction (TPR) | Reducibility, copper speciation, active site distribution | Identifies transformation of active Cu sites to less active or inactive species [16] |

| Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) | Oxidation states, coordination environment of metal sites | Tracks changes in active site geometry and electronic structure [16] |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Framework integrity, local atomic environment | Detects dealumination and framework degradation in zeolite-based catalysts [16] |

Operando Reactor Design Protocol

Objective: To design operando characterization reactors that minimize the gap between characterization conditions and real-world catalytic environments.

Materials and Equipment:

- Electrochemical cell with optical windows

- Mass spectrometry probe with pervaporation membrane

- X-ray transparent windows

- Gas/liquid delivery system

- Reference electrodes

Procedure:

- Reactor Configuration for Mass Transport:

- Implement electrolyte flow and gas diffusion electrodes to control convective and diffusive transport

- Avoid batch operation with planar electrodes when possible to prevent poor mass transport of reactants [2]

- Design flow cells that mimic hydrodynamic conditions of industrial reactors

Minimizing Response Time:

- For DEMS, deposit catalyst directly onto the pervaporation membrane to eliminate long path lengths [2]

- Position reaction event sites in close proximity to spectroscopic probes

- Optimize path length for rapid detection of transient intermediates

Signal-to-Noise Optimization:

- For grazing incidence X-ray diffraction, co-optimize X-ray transmission through liquid electrolyte and beam interaction area

- Minimize contact with aqueous electrolyte to prevent signal attenuation while ensuring sufficient catalyst surface area interaction [2]

Industrial Relevance Considerations:

- Modify end plates of zero-gap reactors with beam-transparent windows for operando XAS

- Design to accommodate current densities of high-performance operation [2]

- Incorporate realistic operating parameters (temperature, pressure, flow rates)

Visualization of Experimental Approaches

Diagram 1: Comprehensive workflow for bridging model and real-world catalytic systems through operando characterization, highlighting the iterative validation process essential for developing predictive models and improved catalysts.

Key Insights from Comparative Studies

Discrepancies Between Laboratory and Real-World Aging

Comparative studies between laboratory-aged and real-world aged catalysts provide crucial insights into the limitations of conventional accelerated aging protocols. Research on Cu/SSZ-13 SCR catalysts has demonstrated that standard laboratory hydrothermal aging only partially replicates the properties of field-aged catalysts. While hydrothermal aging alone reasonably mimics low- and high-temperature NH₃ storage capacities, it poorly reproduces critical performance metrics such as low-temperature deNOx efficiency, high-temperature deNOx efficiency, NH₃ oxidation capacity, and N₂O formation [16]. The inclusion of sulfur in aging protocols (HTA+SOx) shows substantial improvement in mimicking real-world aging but still fails to accurately reproduce NH₃ oxidation and high-temperature SCR properties.

Spectroscopic investigations reveal that these performance discrepancies originate from differences in copper speciation and zeolite framework degradation pathways between laboratory and real-world conditions. While laboratory aging primarily induces dealumination and conversion of active Cu ions to CuO clusters, real-world aging involves more complex transformations, potentially including additional poisoning elements beyond sulfur, multiple pathways for zeolite support degradation, and interactions between different deactivation mechanisms [16]. These findings highlight the necessity of developing more sophisticated multi-stress aging protocols that better simulate the complex chemical environment encountered in practical applications.

Table 2: Performance Discrepancies Between Laboratory-Aged and Real-World Aged Cu/SSZ-13 Catalysts

| Performance Metric | Lab Hydrothermal Aging vs. Real-World | Lab Hydrothermal + Sulfur Aging vs. Real-World |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Temperature deNOx Efficiency | Poor mimicry | Substantially improved but incomplete |

| High-Temperature deNOx Efficiency | Poor mimicry | Poor mimicry |

| NH₃ Oxidation Capacity | Poor mimicry | Poor mimicry |

| N₂O Formation | Poor mimicry | Not specified |

| Low-Temperature NH₃ Storage | Reasonable mimicry | Not specified |

| High-Temperature NH₃ Storage | Reasonable mimicry | Not specified |

Advanced Operando Techniques for Real-World Conditions

Operando characterization techniques have evolved significantly to address the challenges of studying catalysts under realistic conditions. In situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) has progressed to enable the observation of catalysts in gas or liquid environments at elevated temperatures and pressures, providing atomic-scale insights into dynamic processes such as nanoparticle sintering, surface reconstruction, and phase transformations [17]. These capabilities are crucial for understanding catalyst behavior under industrial conditions, as demonstrated by studies on Cu/SSZ-13 catalysts where operando techniques revealed the transformation of active Cu sites to less active or inactive species during real-world operation [16].

Multi-modal characterization approaches that combine complementary techniques are particularly powerful for bridging the model-real world gap. For instance, combining X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) with vibrational spectroscopy (IR, Raman) and electrochemical mass spectrometry (EC-MS) provides correlated information on electronic structure, molecular vibrations, and reaction products simultaneously [2] [12]. Such integrated approaches can distinguish active sites from spectator species—a critical challenge in operando studies of complex catalytic systems like those for the oxygen evolution reaction (OER), where catalyst surfaces often undergo significant reconstruction under operating conditions [12].

Diagram 2: Key design considerations for operando reactors that bridge the gap between characterization conditions and real-world catalytic environments, addressing mass transport, signal quality, and response time challenges.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Operando Characterization Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cu/SSZ-13 Catalysts | Standard SCR catalyst for comparative studies | Use both laboratory-synthesized and commercially formulated samples for aging comparison studies [16] |

| Nitronaphthalimide Probe | Fluorogenic reporter for nitro-to-amine reduction | Enables real-time monitoring of catalytic reduction reactions in well-plate readers [18] |

| Hydrazine Solution | Reducing agent for catalytic reduction studies | Use 1.0 M aqueous N₂H₄ with 0.1 mM acetic acid for nitro-to-amine reduction assays [18] |

| X-ray Transparent Windows | Enable spectroscopic probing during reaction | Materials such as Kapton, silicon nitride, or diamond for various energy ranges [2] |

| Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry Membrane | Interface between electrochemical cell and MS | Deposit catalyst directly onto pervaporation membrane to minimize response time [2] |

| Isotope-labeled Reactants | Mechanistic pathway elucidation | Use ¹⁸O-labeled water or oxygen for distinguishing OER mechanisms [12] |

Implementation Guidelines and Best Practices

Protocol Standardization for Machine Readability

The lack of standardization in reporting synthesis protocols and characterization data significantly hampers machine-reading capabilities and the development of comprehensive catalyst databases. Recent advances in natural language processing and transformer models demonstrate the potential for automated extraction of synthesis protocols from literature, with models capable of converting unstructured procedural descriptions into machine-readable action sequences with approximately 66% accuracy [19]. To enhance the reproducibility and machine-readability of catalytic studies, researchers should:

- Adopt structured reporting templates for synthesis procedures that clearly separate actions, parameters, and conditions

- Include detailed descriptions of aging protocols, including exact temperatures, atmospheres, durations, and contaminant exposures

- Report full characterization parameters alongside performance data to enable correlation analysis

- Provide raw data access for critical operando measurements to support community benchmarking

Mitigating Common Pitfalls in Operando Studies

Operando characterization, while powerful, introduces several potential pitfalls that can lead to misinterpretation of catalyst behavior. To strengthen the validity of conclusions drawn from operando experiments:

- Address Beam-Induced Effects: In techniques like XAS and TEM, high-energy beams can alter catalyst structure or reaction pathways. Implement dose-controlled experiments and validate with complementary techniques [17] [12].

- Control for Mass Transport Limitations: Operando reactor designs often differ substantially from industrial reactors in hydrodynamics and transport properties. Incorporate flow systems and gas diffusion electrodes where possible to better mimic practical conditions [2].

- Distinguish Active Sites from Spectator Species: Many operando signals originate from both active and inactive species. Use selective poisoning, isotope labeling, and correlation with activity measurements to identify true active sites [12].

- Validate with Multiple Techniques: Rely on multi-modal approaches to cross-validate findings, as each technique has inherent limitations and artifacts [2] [12].

Bridging the gap between model systems and real-world catalytic environments remains a formidable challenge in catalysis research, but significant progress is being made through advanced operando characterization techniques. The integration of sophisticated aging protocols, multi-modal characterization, and machine-readable data reporting provides a pathway to more predictive catalyst design and evaluation. Future advances will likely come from several directions: the development of more realistic aging protocols that incorporate multiple stressors simultaneously; improved operando reactor designs that better mimic industrial conditions while maintaining characterization capabilities; and the integration of machine learning approaches to extract deeper insights from multi-technique datasets. By embracing these approaches, the catalysis community can accelerate the development of high-performance catalysts designed for stability and activity under real-world operating conditions, ultimately enabling more efficient and sustainable chemical processes.

Advanced Operando Techniques: Methodologies and Cutting-Edge Applications

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS) is a powerful element-specific analytical technique that provides detailed information about the local electronic structure and atomic coordination environment of a selected element within a material. As a core technique at synchrotron facilities worldwide, XAS has become indispensable for materials characterization across diverse fields including catalysis, energy materials, and pharmaceutical sciences [20] [21]. The technique is particularly valuable for studying amorphous, disordered, or multicomponent systems where long-range order is absent [22].

For catalyst analysis, XAS offers unique capabilities for probing operando conditions, enabling researchers to capture the dynamic structural evolution of catalysts under actual working environments [4] [23]. This application note details the fundamental principles, experimental protocols, and data analysis methods for utilizing XAS in operando characterization of catalysts, with specific focus on electrochemical systems relevant to energy conversion technologies.

Fundamental Principles of XAS

Physical Basis

XAS measures the absorption coefficient (μ) of a material as a function of incident X-ray photon energy [21]. When the energy of incident X-rays reaches the binding energy of core-level electrons (e.g., 1s, 2s, or 2p orbitals) of a specific element, a sharp increase in absorption occurs known as the absorption edge [21]. This element-specific edge enables targeted study of selected elements through appropriate tuning of the excitation energy.

The ejected photoelectron scatters from neighboring atoms, creating interference patterns that encode structural information. The XAS spectrum is typically divided into two regions:

- X-ray Absorption Near Edge Structure (XANES): Extends from the pre-edge to approximately 50 eV above the absorption edge, providing information about oxidation state, electronic structure, coordination symmetry, and bond characterization [24].

- Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (EXAFS): Ranges from 50 to 1000 eV above the edge, yielding quantitative data on bond lengths, coordination numbers, and disorder factors of neighboring atoms [24].

Measurement Geometries

XAS measurements can be performed in several geometries, each with specific advantages for different sample types:

Table 1: XAS Measurement Modes and Applications

| Measurement Mode | Principle | Optimal Sample Characteristics | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transmission [21] | Measures intensity of radiation before (I₀) and after (I𝑡) passing through sample | Homogeneous samples with >10% target element concentration; powder pellets, solutions, solid materials | High-quality spectra with short acquisition time; direct measurement of absorption coefficient | Requires specific sample thickness and homogeneity |

| Fluorescence [21] | Measures characteristic X-ray radiation (I𝑓) emitted after atomic relaxation processes | Thin films, highly diluted solutions, or samples with low concentration of absorber element (<5 wt%) | High sensitivity for dilute elements; minimal sample preparation | Self-absorption effects can distort spectra |

| Electron Yield [21] | Measures electrons emitted as a result of absorption | Surface-sensitive studies; ultra-thin films | Extreme surface sensitivity (top 1-10 nm) | Requires ultra-high vacuum; not suitable for liquid samples |

For operando catalyst studies, fluorescence detection is often preferred due to its sensitivity to low metal loadings typical in supported catalysts, and its compatibility with electrochemical cell designs [25].

Experimental Protocols for Operando XAS

Specialized Electrochemical Cell Design

Operando XAS studies of electrocatalysts require specialized electrochemical cells that maintain functionality while allowing optimal X-ray transmission and detection. A recently developed cell design enables simultaneous XRD and XAS measurements in both fluorescence and transmission modes [25].

Key Design Features:

- Material Selection: Main components constructed from polyether ether ketone (PEEK) and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) for stability across pH range 0-14 [25].

- X-ray Windows: Kapton membranes provide low-absorption windows for X-ray transmission [25].

- Angled Geometry: 45° slope on X-ray receiving window enables both transmission and fluorescence detection, with near 90° angle between incident beam and fluorescence detector [25].

- Flow System: Integrated flow channels enable efficient removal of gas products during operation [25].

- Adjustable Electrolyte Thickness: Capability to minimize X-ray absorption by optimizing electrolyte layer thickness [25].

Electrode Configuration:

- Working electrode: Catalyst-coated carbon paper (typically 10×10 mm coating area) [25]

- Counter and reference electrodes inserted through 3 mm diameter access ports [25]

- Symmetrical design with rotating caps for secure sealing

Protocol: Operando XAS of Electrocatalysts

Materials Preparation:

- Catalyst Synthesis: Prepare supported nanocatalysts (e.g., 40 wt% Mn₃O₄/C, Co₃O₄/C) using colloidal approach [23].

- Working Electrode Preparation:

- Cut carbon paper to 10×20 mm strip

- Apply catalyst ink via drop-casting to create 10×10 mm active area

- Dry under inert atmosphere

- Electrolyte Preparation: Use 0.1 M KOH for alkaline conditions or other appropriate electrolyte depending on catalytic reaction

Data Collection Procedure:

Cell Assembly:

- Mount working electrode in cell holder

- Position reference and counter electrodes through access ports

- Assemble cell with Kapton windows, ensuring proper sealing with O-rings

- Fill electrolyte reservoir, ensuring no air bubbles in X-ray path

Beamline Alignment:

- Align X-ray beam to illuminate catalyst layer on working electrode

- Position fluorescence detector at 45° to sample surface normal

- Position transmission ion chambers before and after sample

- Optimize beam position for simultaneous fluorescence and transmission detection

Operando Measurement:

- Apply potentiostatic control to working electrode

- Collect XANES spectra at relevant applied potentials (e.g., 0.2-1.2 V vs. RHE)

- For time-resolved studies, utilize quick-scanning XAFS (QXAFS) with second-scale time resolution [24]

- Monitor electrochemical response (current) simultaneously with spectral acquisition

Data Collection Parameters:

- Energy range: -50 to +800 eV relative to absorption edge

- Integration time: 1-5 seconds per point for QXAFS [24]

- Multiple scans (3-5) for improved signal-to-noise ratio

- Reference foil spectrum collected simultaneously for energy calibration

Data Analysis Workflow

Processing and Interpretation

The analysis of XAS data follows a systematic workflow to extract quantitative structural and electronic information:

XANES Analysis for Electronic Structure

XANES spectra provide quantitative information about oxidation states and electronic configuration:

Linear Combination Fitting (LCF):

- Mathematical decomposition of spectra into reference components

- Quantifies phase composition changes under operando conditions

- Requires high-quality reference spectra of potential phases

Edge Position Analysis:

- Determine oxidation state from energy shift of absorption edge

- Calibrate using reference compounds of known oxidation state

- Typical sensitivity: ~1-2 eV per oxidation state change

Table 2: XANES Features and Their Structural Significance

| Feature | Energy Region | Structural Information | Analysis Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-edge | 10-20 eV below edge | Coordination symmetry, orbital hybridization | Peak position, intensity, shape analysis |

| Edge Position | At absorption edge | Formal oxidation state | Comparison to reference compounds |

| White Line | 0-30 eV above edge | Density of unoccupied states | Peak intensity, area measurement |

| Edge Shape | 0-50 eV above edge | Coordination geometry, bond covalency | Fingerprint comparison, PCA |

EXAFS Analysis for Local Coordination

EXAFS analysis provides quantitative local structural parameters:

Fourier Transform:

- Convert k-space oscillations to R-space for real-space interpretation

- Identify coordination shells and approximate interatomic distances

Theoretical Fitting:

- Fit experimental data with theoretical models generated from FEFF or similar codes

- Extract quantitative parameters: coordination number (N), bond distance (R), and disorder factor (σ²)

Key Parameters from EXAFS:

- Coordination numbers: Identify structural motifs (e.g., tetrahedral vs. octahedral)

- Bond distances: Precision of ±0.02 Å for first shell

- Disorder factors: Quantify structural disorder or static distortion