Overcoming Domain Shift: A Practical Guide for Applying Catalyst Generative AI in Drug Discovery

Catalyst generative models promise to revolutionize molecular design, but their real-world application is hampered by domain shift—the performance gap between training data and target domains.

Overcoming Domain Shift: A Practical Guide for Applying Catalyst Generative AI in Drug Discovery

Abstract

Catalyst generative models promise to revolutionize molecular design, but their real-world application is hampered by domain shift—the performance gap between training data and target domains. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals. We first define the core problem and its impact on predictive accuracy. We then explore advanced methodological approaches for model adaptation and deployment. A dedicated troubleshooting section addresses common pitfalls and optimization strategies. Finally, we establish rigorous validation protocols and comparative benchmarks to ensure model reliability. This guide synthesizes current best practices to bridge the gap between in-silico catalyst design and successful experimental validation.

Domain Shift Decoded: Why Catalyst AI Models Fail in Real-World Applications

This technical support center addresses key challenges in catalyst discovery, specifically the domain shift between in-silico generative model predictions and in-vitro experimental validation. This content supports the broader thesis on Addressing domain shift in catalyst generative model applications research.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our generative model predicts a high catalyst activity score, but the in-vitro assay shows negligible reaction rate. What are the primary causes? A: This is a classic manifestation of domain shift. Common causes include:

- Solvent & Environment Mismatch: The model was trained on quantum mechanics (QM) data in a vacuum or implicit solvent, while the experiment is in an aqueous or complex buffer.

- Descriptor Failure: The molecular descriptors/features used for training do not capture the critical physical-organic chemistry parameters relevant to the experimental condition (e.g., ionic strength, pH sensitivity).

- Hidden Deactivation Pathways: The catalyst decomposes or is poisoned by impurities under experimental conditions not modeled in-silico.

Q2: How can we diagnose if poor in-vitro performance is due to a domain shift versus a flawed experimental protocol? A: Implement a control ladder:

- Replicate a Known Catalyst: Test a literature-known catalyst with your protocol to confirm baseline functionality.

- Compute-Experiment Pairing: Run the exact experimental conditions (solvent, temperature, concentration) through a higher-level simulation (e.g., explicit solvent MD/DFT) for a small subset of candidates. Compare the trend (relative performance), not absolute values.

- Systematic Variation: If resources allow, perform a low-fidelity experimental screen (e.g., 24-well plate) varying one condition at a time (pH, solvent, additive) to see if performance aligns with model predictions under any condition.

Q3: What strategies can mitigate domain shift when fine-tuning a generative model for our specific experimental setup? A:

- Transfer Learning with Sparse Data: Use a pre-trained generative model and fine-tune its final layers on a small, high-quality dataset (even 10-20 data points) from your own lab.

- Multi-Fidelity Modeling: Train the model on a combination of high-fidelity (expensive, accurate) and low-fidelity (cheap, noisy) experimental data to learn the correction function.

- Domain Adversarial Training: During model training, incorporate a domain classifier that tries to distinguish between in-silico and in-vitro data. The primary network is trained to "fool" this classifier, learning domain-invariant features.

Q4: Which experimental validation step is most critical to perform first after in-silico screening to check for domain shift? A:Stability Assessment.* Before full activity assay, subject the top *in-silico candidates to analytical techniques (e.g., LC-MS, NMR) under the reaction conditions to check for decomposition. A stable but inactive catalyst narrows the shift to electronic/steric descriptor failure, while decomposition points to a stability domain gap.

Table 1: Common Sources of Domain Shift and Diagnostic Experiments

| Source of Shift | In-Silico Assumption | In-Vitro Reality | Diagnostic Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvation Effects | Implicit solvent (e.g., SMD) or vacuum. | Complex solvent mixture, high ionic strength. | Measure activity in a range of solvent polarities; compare to implicit solvent model trends. |

| Catalyst Stability | Optimized ground-state geometry. | Oxidative/reductive decomposition, hydrolysis. | Pre-incubate catalyst without substrate, then add substrate and measure lag phase. |

| Mass Transfer | Idealized, instantaneous mixing. | Diffusion-limited in batch reactor. | Vary stirring rate; use a smaller catalyst particle size or a flow reactor. |

| pH Sensitivity | Fixed protonation state. | pH-dependent activity & speciation. | Measure reaction rate across a pH range. |

Table 2: Performance Metrics Indicative of Domain Shift

| Metric | In-Silico Dataset | In-Vitro Dataset | Significant Shift Indicated by |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top-10 Hit Rate | 80% (simulated yield >80%) | 10% (experimental yield >80%) | >50% discrepancy. |

| Rank Correlation (Spearman's ρ) | N/A (compared to ground truth sim.) | ρ < 0.3 between predicted and expt. activity rank. | Low or negative correlation. |

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | MAE < 5 kcal/mol (for energy predictions) | MAE > 3 log units in turnover frequency (TOF). | Error exceeds experimental noise floor. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Catalyst Stability Pre-Screening (LC-MS) Objective: To identify catalyst decomposition prior to full activity assay. Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" below. Method:

- Prepare a 1 mM solution of the catalyst candidate in the planned reaction solvent.

- Incubate the solution at the planned reaction temperature in a vial.

- At t = 0, 15 min, 1 hr, and 6 hrs, withdraw a 50 µL aliquot.

- Quench the aliquot immediately (e.g., dilute 1:10 in cold acetonitrile) and store on ice.

- Analyze all quenched samples via LC-MS (ESI+/-) using a method suitable for the catalyst's polarity.

- Monitor the peak area of the parent catalyst ion. A decrease >20% over 1 hr indicates significant instability.

Protocol 2: Cross-Domain Validation via Microscale Parallel Experimentation Objective: To efficiently test the impact of a key experimental variable (e.g., solvent) predicted to cause shift. Method:

- Select 3-5 top in-silico candidates and 1-2 known reference catalysts.

- In a 96-well plate, set up reactions with each catalyst in 3 different solvents: one matching the in-silico condition (e.g., toluene), one polar aprotic (e.g., DMF), and one protic (e.g., methanol). Keep all other variables constant.

- Run reactions in parallel using an automated liquid handler or multi-channel pipette.

- Quench reactions at a fixed, early time point (e.g., 30 mins) to measure initial rates.

- Analyze yields/conversions via UPLC or GC.

- Analysis: If catalyst performance rankings change dramatically with solvent, a solvation-related domain shift is confirmed.

Diagrams

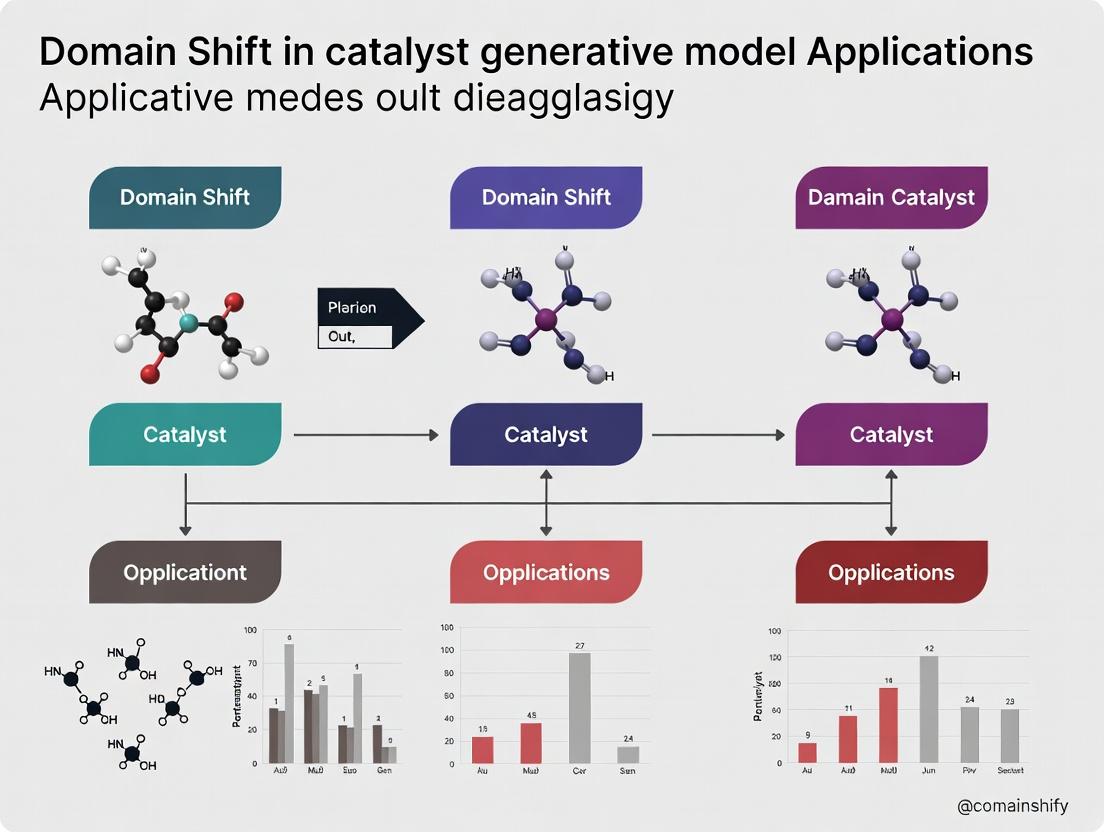

Diagram 1: Domain Shift in Catalyst Discovery Workflow

Diagram 2: Strategy to Mitigate Domain Shift

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Primary Function in Context | Notes for Domain Shift |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents (DMSO-d₆, CDCl₃) | NMR spectroscopy for reaction monitoring & catalyst stability. | Critical for diagnosing decomposition (shift) in real-time. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents (Acetonitrile, Methanol) | Mobile phase for analytical LC-MS to assess catalyst purity & stability. | Ensures detection of low-abundance decomposition products. |

| Solid-Supported Reagents (Scavengers) | Remove impurities in-situ that may poison catalysts. | Can rescue in-vitro performance if shift is due to trace impurities. |

| Inert Atmosphere Glovebox | Enables handling of air/moisture-sensitive catalysts & reagents. | Eliminates oxidation/hydrolysis shifts not modeled in-silico. |

| High-Throughput Screening Kits (e.g., catalyst plates) | Enables rapid parallel testing of candidates under varied conditions. | Essential for generating small, fine-tuning datasets. |

| Calibration Standards (for GC/UPLC) | Quantifies reaction conversion/yield accurately. | Provides the reliable experimental data needed for model correction. |

| Stable Ligand Libraries | Provides a baseline for comparing novel generative candidates. | A known-performing ligand set helps isolate shift to the catalyst core. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Section 1: Chemical Space Shift

Q1: My generative model, trained on organometallic catalysts for C-C coupling, performs poorly when generating suggestions for photocatalysts. What is the issue and how can I address it? A: This is a classic chemical space domain shift. The model has learned features specific to transition metal complexes (e.g., coordination geometry, d-electron count) which are not directly transferable to organic photocatalysts (e.g., conjugated systems, triplet energy). To troubleshoot:

- Diagnose: Perform a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or t-SNE on the learned latent representations of your training set versus target photocatalyst structures. You will likely see minimal overlap.

- Mitigate: Implement a domain adaptation technique. Use a small set of known photocatalysts (~100-200 structures) and employ a gradient reversal layer (GRL) during fine-tuning to learn domain-invariant features, forcing the encoder to extract representations common to both catalyst types.

Q2: How do I quantify the chemical space shift between my training data and target application? A: Use calculated molecular descriptor distributions. Key metrics are summarized below.

Table 1: Quantitative Descriptors for Diagnosing Chemical Space Shift

| Descriptor Class | Specific Metric | Typical Range (Training: Organometallics) | Typical Range (Target: Photocatalysts) | Significant Shift Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elemental | Presence of Transition Metals | High (>95%) | Very Low (<5%) | Yes |

| Topological | Average Molecular Weight | 300-600 Da | 200-400 Da | Potentially |

| Electronic | HOMO-LUMO Gap (calculated DFT) | 1-3 eV | 2-4 eV | Yes |

| Complexity | Synthetic Accessibility Score (SAScore) | Moderate-High | Moderate | Possibly |

Protocol for Descriptor Calculation:

- Generate a representative sample (n=500) from both your training dataset and your target domain of interest.

- Use RDKit (

rdkit.Chem.Descriptors) or a DFT package (e.g., ORCA for HOMO-LUMO) to compute descriptors. - Perform a two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test on each descriptor distribution. A p-value < 0.01 indicates a statistically significant shift.

Section 2: Reaction Conditions Shift

Q3: The model predicts high yields for reactions in THF, but experimental validation in acetonitrile fails. How can I condition my model for solvent effects? A: Your model lacks conditioning on critical reaction parameters. You need to augment the model input to include condition vectors.

- Solution: Retrain or fine-tune your model using a dataset where reactions are annotated with condition tags (e.g., solvent one-hot encoding, temperature, concentration).

- Implementation: Append a condition vector

C(e.g., [solvent_type, temp, conc]) to the latent vectorzbefore the decoder. This allows generation conditional on specified parameters.

Q4: What are the minimum experimental data required to adapt a generative model to a new set of reaction conditions? A: The required data depends on the number of variable conditions. A designed experiment (DoE) is optimal.

Table 2: Minimum Dataset for Conditioning on Solvent & Temperature

| Condition 1 (Solvent) | Condition 2 (Temp °C) | Number of Unique Catalysts to Test | Replicates | Total Data Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent A, Solvent B | 25, 80 | 10 (sampled from model) | 3 | 10 catalysts * 4 condition combos * 3 reps = 120 reactions |

Protocol for Condition-Aware Fine-Tuning:

- Data Collection: Run the small experimental matrix from Table 2, measuring yield or turnover number (TON).

- Data Encoding: Create a paired dataset:

(Catalyst SMILES, Condition Vector, Yield). - Model Update: Freeze the encoder. Fine-tune the decoder and the conditioning layers on the new paired dataset using a mean-squared error loss on the predicted yield.

Section 3: Biological Context Shift

Q5: My catalyst model for in vitro ester hydrolysis fails to predict effective catalysts in cellular lysate. What could be causing this? A: This is a biological context shift. The in vitro assay lacks biomolecular interferants (e.g., proteins, nucleic acids) that can deactivate catalysts or compete for substrates.

- Troubleshoot: Run a control experiment to test for catalyst deactivation. Incubate the catalyst in lysate, then remove biomolecules via size-exclusion chromatography. Test the recovered catalyst's activity in the pure in vitro assay. A loss of activity suggests irreversible binding or decomposition.

- Adaptation: Incorporate "biological context" descriptors during training. Use catalyst SMILES to predict simple properties like logP (lipophilicity) and charge, which correlate with non-specific protein binding. Use these as negative conditioning signals.

Q6: How can I screen generative model outputs for potential off-target biological activity early in the design cycle? A: Implement a parallel in silico off-target screen as a filter.

Protocol for Off-Target Screening Filter:

- Generate: Produce a batch of 1000 candidate catalysts from your generative model.

- Filter (Step 1): Use a rule-based filter (e.g., PAINS filter) to remove motifs known to promiscuously bind proteins.

- Filter (Step 2): For remaining candidates, run a similarity search (Tanimoto fingerprint) against a database of known bioactive molecules (e.g., ChEMBL). Flag candidates with high similarity (>0.85) for manual review before synthesis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Evaluating Catalyst Domain Shift

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents Set (CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆, etc.) | NMR spectroscopy for reaction monitoring and catalyst integrity verification. | Confirming catalyst stability under new reaction conditions. |

| Size-Exclusion Spin Columns (e.g., Bio-Gel P-6) | Rapid separation of small molecule catalysts from biological macromolecules. | Testing for catalyst deactivation in biological lysates (FAQ #5). |

| Common Catalyst Poisons (Mercury drop, P(4)-Bu₃, CS₂) | Diagnostic tools for homogeneous vs. heterogeneous catalysis pathways. | Understanding catalyst failure modes in new chemical spaces. |

| Computational Ligand Library (e.g., the Cambridge Structural Database) | Source of diverse 3D ligand geometries for data augmentation. | Mitigating chemical space shift by expanding training set diversity. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Kit (e.g., 96-well reactor block) | Enables rapid empirical testing of condition matrices. | Generating adaptation data for reaction condition shift (FAQ #4). |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Chemical Space Shift Causing Model Failure

Diagram 2: Model Conditioning for Reaction Parameters

Diagram 3: Biological Context Shift from In Vitro to Complex Media

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Generative Model Performance in Catalyst Discovery

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our generative model, trained on heterocyclic compound libraries, performs poorly when generating candidates for transition-metal catalysis. What is the likely cause? A1: This is a classic case of scaffold distribution shift. Your training domain (heterocycles for organic catalysis) differs fundamentally from the target domain (ligands for transition metals). The model lacks featurization for d-orbital geometry and electron donation/back-donation properties.

Q2: We validated our catalyst generator using a random train/test split from a public dataset, but all synthesized candidates showed low turnover frequency (TOF). Why? A2: Random splitting within a single source dataset fails to detect temporal or provenance shift. Your test set was likely from the same literature period or lab as your training data, sharing hidden biases. Real-world application introduces new synthetic conditions and purity standards not represented in the training corpus.

Q3: After fine-tuning a protein-ligand interaction model on new assay data, its prediction accuracy for our target class dropped significantly. How do we diagnose this? A3: This indicates fine-tuning shift or "catastrophic forgetting." The fine-tuning process has likely caused the model to lose generalizable knowledge from its original pre-training. You must implement elastic weight consolidation or perform parallel evaluation on the original task during fine-tuning.

Q4: Our generative model produces chemically valid structures, but they are consistently unsynthesizable according to our medicinal chemistry team. What shift is occurring? A4: This is an expert knowledge vs. data shift. The model is optimizing for statistical likelihood learned from published data, which over-represents novel, publishable (often complex) structures. It has not learned the tacit, unpublished heuristic rules (e.g., step count, protective group complexity) used by synthetic chemists.

Q5: How can we detect a potential domain shift before committing to expensive synthesis and testing? A5: Implement a pre-deployment shift detection battery:

- Statistical: Compare latent space distributions (e.g., using Maximum Mean Discrepancy - MMD) between training data and generated candidate pools.

- Proxy Model: Train a simple classifier to distinguish between training and generated data. If it succeeds with high accuracy, significant shift exists.

- Property Drift Analysis: Compare key physicochemical property distributions (e.g., molecular weight, logP, ring count) between datasets.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor External Validation Performance After Successful Internal Validation Symptoms: High AUC/ROC during internal cross-validation, but poor correlation between predicted and actual pIC50/TOF in new external test sets. Diagnostic Steps:

- Check Data Provenance: Create a table of metadata for your training and new test data.

| Data Source Characteristic | Training Data | New Test Data | Shift Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Literature Year (Avg.) | 2010-2015 | 2018-2023 | High (Temporal) |

| Assay Type (e.g., FRET vs. SPR) | FRET-based | SPR-based | High (Technical) |

| Organism (for protein targets) | Recombinant Human | Rat Primary Cell | High (Biological) |

| pH of Assay Buffer | 7.4 | 7.8 | Medium |

- Protocol for Covariate Shift Correction (Importance Reweighting):

- Step 1: Concatenate your training features (Xtrain) and new application/data features (Xnew).

- Step 2: Label the source (0 for train, 1 for new).

- Step 3: Train a probabilistic classifier (e.g., logistic regression) to distinguish between the two sources.

- Step 4: For each training sample i, calculate its probability of coming from the new distribution: P(source=1 | xi).

- Step 5: Compute the importance weight: wi = P(source=1 | xi) / P(source=0 | xi).

- Step 6: Retrain your primary generative or predictive model using these weights on the training data. This forces the model to pay more attention to training samples that resemble the new domain.

Issue: Model Generates Physically Implausible Catalytic Centers Symptoms: Generated molecular graphs contain forbidden coordination geometries or unstable oxidation states for the specified transition metal (e.g., square planar carbon, Pd(V) complexes). Root Cause: Knowledge Graph Shift. The training data's implicit rules of inorganic chemistry are incomplete or biased towards common states, failing to constrain the generative process. Mitigation Protocol:

- Constrained Generation Workflow:

- Step 1: Define explicit valency and coordination number rules for the target metal as a "hard" filter in the generation loop.

- Step 2: Integrate a rule-based post-processing checker using SMARTS patterns or a lightweight quantum mechanics (QM) calculator (e.g., GFN2-xTB) to screen all generated structures.

- Step 3: Implement reinforcement learning with a penalty term in the reward function that severely punishes physically implausible structures.

Visualizations

Title: Workflow Showing Point of Failure Due to Temporal Shift

Title: Representational Shift in Catalyst Cycle Modeling

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item & Vendor Example | Function in Addressing Shift | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets with Metadata (e.g., Catalysis-Hub.org, PubChemQC with source tags) | Provides multi-domain data for testing model robustness. Enables controlled shift simulation. | Critical: Must include detailed assay conditions, year, and lab provenance metadata. |

| Domain Adaptation Libraries (e.g., DANN in PyTorch, AdaBN) | Implements algorithms to align feature distributions between source (training) and target (new) domains. | Works best when shift is primarily in feature representation, not label space. |

| Constrained Generation Framework (e.g., Reinvent 3.0 with custom rules, PyTorch-IE) | Allows imposition of expert knowledge (e.g., valency rules, synthetic accessibility) as hard constraints during generation. | Prevents model from exploiting gaps in training data to generate implausible candidates. |

| Explainable AI (XAI) Tools (e.g., SHAP, LIME for graphs) | Diagnoses which features drive predictions, revealing if model relies on spurious correlations from source domain. | Helps distinguish between true catalytic drivers and dataset artifacts. |

| Fast Quantum Mechanics (QM) Calculators (e.g., GFN2-xTB, ANI-2x) | Provides rapid, physics-based validation of generated structures (geometry, energy) before synthesis. | Acts as a "reality check" against data-driven model hallucinations or extrapolations. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting for Catalyst Generative Models

Thesis Context: This support center is designed to assist researchers in Addressing domain shift in catalyst generative model applications. Domain shift occurs when a model trained on one dataset (e.g., homogeneous organometallic catalysts) underperforms when applied to a related but different domain (e.g., heterogeneous metal oxide catalysts), limiting generalization.

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: Our generative model, trained on transition-metal complexes, produces invalid or unrealistic structures when we shift to exploring main-group catalysts. What is the primary cause? A1: This is a classic input feature domain shift. The model's latent space is structured around the geometric and electronic parameters of transition metals. Main-group elements exhibit different common coordination numbers, bonding angles, and redox properties not well-represented in the training data.

- Solution: Implement a feature alignment strategy. Retrain the model's encoder using a contrastive loss on a mixed dataset containing both transition-metal and main-group complexes, forcing it to learn a more unified representation.

Q2: When using a pretrained catalyst property predictor to guide our generative model, the predicted activity scores become unreliable for a new catalyst family. How can we correct this? A2: This is a label/prediction shift. The property predictor's performance degrades due to changes in the underlying relationship between catalyst structure and target property (e.g., turnover frequency) in the new domain.

- Solution: Apply transfer learning with sparse data. Freeze the early layers of the predictor network and fine-tune the final layers using a small, high-fidelity dataset (10-50 samples) of the new catalyst family. This recalibrates the prediction head.

Q3: Our generative model exhibits "mode collapse," generating only minor variations of a single catalyst scaffold when tasked with exploring a new chemical space. How do we overcome this? A3: This often stems from a narrow prior distribution in the model's latent space, compounded by a reward function (from a critic/predictor) that is too strict or poorly calibrated for the new domain.

- Solution:

- Diversity Regularization: Add a penalty term to the loss function that maximizes the pairwise distance between generated structures in a batch.

- Adversarial Validation: Train a classifier to distinguish between your original training set and newly generated samples. Use the classifier's outputs to reward the generator for producing samples that "fool" it into thinking they belong to the original domain, effectively exploring its boundaries.

Q4: We lack any experimental data for the new catalyst domain we want to explore. How can we assess the reliability of our generative model's outputs? A4: In this zero-shot generalization scenario, rely on computational validation tiers.

- Solution Protocol:

- Tier 1 (Structural): Filter all generated structures using hard chemical rules (e.g., valency, unfavorable steric clashes via molecular mechanics).

- Tier 2 (Electronic): Perform low-level DFT (e.g., GFN2-xTB) on filtered candidates to assess stability and basic electronic structure.

- Tier 3 (Performance): Run high-fidelity DFT (e.g., hybrid functionals, solvation models) on the top 1% of Tier-2 candidates to predict key catalytic descriptors (e.g., adsorption energies, activation barriers).

Table 1: Performance Drop Due to Domain Shift in Catalyst Property Prediction (MAE on Test Set)

| Model Architecture | Training Domain (Source) | Test Domain (Target) | Source MAE (eV) | Target MAE (eV) | % Increase in Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Pt/Pd-based surfaces (OCP) | Au/Ag-based surfaces | 0.15 | 0.42 | 180% |

| 3D-CNN | Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Covalent Organic Frameworks | 0.08 | 0.31 | 288% |

| Transformer | Homogeneous Organocatalysts | Homogeneous Photocatalysts | 0.12 | 0.28 | 133% |

Table 2: Efficacy of Generalization Techniques for Catalyst Design

| Technique | Base Model | Generalization Metric (Top-10 Hit Rate*) | Source Domain | Target Domain | Relative Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vanilla Fine-Tuning | G-SchNet | 15% | Enzymes | Abzymes | Baseline |

| Domain-Adversarial Training | G-SchNet | 38% | Enzymes | Abzymes | +153% |

| Algorithmic Robustness (MAML) | CGCNN | 41% | Perovskites | Double Perovskites | +141% |

| Zero-Shot with RL | JT-VAE | 22% | C-N Coupling | C-O Coupling | N/A |

*Hit Rate: Percentage of top-10 generative model suggestions later validated by high-throughput screening or experiment to be high-performing.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Domain-Adversarial Training of a Catalyst Generator Objective: To train a model that generates valid catalysts across two distinct domains (e.g., porous materials and dense surfaces).

- Data Curation: Assemble datasets A (porous) and B (dense). Ensure consistent feature representation (e.g., Voronoi tessellation features, electronic density maps).

- Model Architecture: Build a generator (G), a domain critic (D), and a property predictor (P). G encodes structure to a latent vector

z. D tries to predict ifzcomes from domain A or B. P predicts the target property (e.g., adsorption energy). - Training:

- Step 1: Train P on labeled data from both domains to predict the property.

- Step 2: Jointly train G, D, and P. G aims to: (i) maximize property prediction from P, (ii) minimize the domain classification accuracy of D (gradient reversal layer), and (iii) produce realistic structures via a reconstruction loss.

- Validation: Generate structures for a target domain. Validate with Tier 1-3 computational checks (see FAQ A4).

Protocol 2: Few-Shot Adaptation of a Reaction Outcome Predictor Objective: Adapt a model trained on Cu-catalyzed reactions to predict outcomes for Ni-catalyzed reactions with <50 data points.

- Base Model: Use a pretrained message-passing neural network (MPNN) on a large dataset of Cu-catalyzed C-N couplings.

- Adaptation Data: Collect a small, high-quality dataset of 30 Ni-catalyzed analogous reactions.

- Fine-Tuning: Freeze 70% of the MPNN's early layers (responsible for general bond and functional group understanding). Unfreeze and train the later layers and the final regression head on the Ni dataset. Use a low learning rate (1e-5) and strong regularization (e.g., dropout, weight decay).

- Evaluation: Test the adapted model on a held-out set of Ni-catalyzed reactions. Compare MAE/R² against the base model and a model trained from scratch on the small dataset.

Visualizations

Domain-Adversarial Training Workflow for Catalysts

Generalization Problem Diagnostic Tree

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools & Datasets for Generalization Research

| Item Name & Provider | Function in Addressing Domain Shift | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Open Catalyst Project (OCP) Dataset (Meta AI) | Provides massive, multi-domain (surfaces, nanoparticles) catalyst data. Serves as a primary source for pre-training and benchmarking generalization. | Training foundation models for heterogeneous catalysis; evaluating cross-material performance drop. |

| Catalysis-Hub.org (SUNCAT) | Repository of experimentally validated and DFT-calculated reaction energetics across diverse catalyst types. Enables construction of small, targeted fine-tuning datasets. | Sourcing sparse data for transfer learning to specific, novel catalyst families. |

| GemNet / SphereNet Architectures (KIT, TUM) | Advanced GNNs that explicitly model directional atomic interactions and 3D geometry. More robust to geometric variations across domains. | Core model for property prediction and generative tasks where spatial arrangement is critical. |

| SchNetPack & OC20 Training Tools | Software frameworks with built-in implementations of energy-conserving models, domain-adversarial losses, and multi-task learning. | Rapid prototyping and deployment of generalization techniques like DANN on catalyst systems. |

| DScribe Library (Aalto University) | Computes standardized material descriptors (e.g., SOAP, Coulomb matrices) for diverse systems. Enforces consistent feature representation across domains. | Input feature engineering and alignment for combining molecular and solid-state catalyst data. |

Bridging the Gap: Methodologies to Adapt and Deploy Robust Catalyst AI

Transfer Learning & Fine-Tuning Strategies for Limited Target Domain Data

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: I am fine-tuning a pre-trained generative model on a small dataset of catalyst molecules (<100 samples). The model quickly overfits, producing high training accuracy but poor, non-diverse validation structures. What are the primary strategies to mitigate this? A: This is a classic symptom of overfitting with limited data. Implement the following protocol:

- Stronger Regularization: Increase dropout rates (e.g., from 0.1 to 0.3-0.5) within the model architecture during fine-tuning. Apply weight decay (L2 regularization) with values between 1e-4 and 1e-6.

- Progressive Unfreezing: Do not fine-tune all layers simultaneously. Start by fine-tuning only the final 1-2 decoder/classifier layers for a few epochs, then progressively unfreeze earlier layers while reducing the learning rate.

- Data Augmentation on Graphs: For molecular graphs, employ domain-informed augmentation such as bond rotation, atom/functional group masking, or valid substructure replacement to artificially enlarge your training set.

- Early Stopping with a Strict Patience: Monitor the validation loss (e.g., negative log-likelihood of valid structures) and stop training when it fails to improve for 5-10 epochs.

Q2: During transfer learning for catalyst design, how do I quantify and address the "domain shift" between my source dataset (e.g., general organic molecules) and my small target dataset (specific catalyst complexes)? A: Quantifying and addressing domain shift is critical. Follow this experimental protocol:

- Quantification: Use a domain classifier. Take the latent representations (embeddings) of molecules from both source and target domains from a fixed pre-trained model. Train a simple classifier (e.g., logistic regression) to distinguish between the two domains. High classification accuracy indicates significant domain shift in the latent space.

- Addressing Shift via Adversarial Adaptation: Incorporate a Gradient Reversal Layer (GRL) during fine-tuning. The primary objective remains to generate valid target catalyst structures, while the GRL trains the feature encoder to produce latent representations that cannot be classified by the domain classifier, thereby aligning the source and target feature distributions.

Diagram Title: Adversarial Domain Adaptation with a Gradient Reversal Layer

Q3: What are the best practices for selecting layers to freeze or fine-tune when adapting a pre-trained molecular Transformer model? A: The strategy depends on data similarity. Use this comparative guide:

| Target Data Size & Similarity to Source | Recommended Fine-Tuning Strategy | Rationale & Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Very Small (<50), Highly Similar | Feature Extraction: Freeze all pre-trained layers. Train only a new, simple prediction head (e.g., FFN). | Pre-trained features are already highly relevant. Prevents catastrophic forgetting. Protocol: Attach new layers, freeze backbone, train with low LR (~1e-4). |

| Small (50-500), Moderately Similar | Partial Fine-Tuning: Use progressive unfreezing (bottom-up). Fine-tune only top 2-4 decoder layers. | Higher layers are more task-specific. Allows adaptation of abstract representations without distorting general chemistry knowledge in lower layers. |

| Moderate (500-5k), Somewhat Different | Full Fine-Tuning with Discriminative Learning Rates. | All layers can adapt. Protocol: Apply lower LR to early layers (e.g., 1e-5) and higher LR to later layers (e.g., 1e-4) to gently shift representations. |

Q4: My fine-tuned model generates chemically valid molecules, but they lack the desired catalytic activity profile. How can I integrate simple property predictors to guide the generation? A: You need to implement a conditional generation or RL-based optimization loop.

- Train a Property Predictor: Train a separate, simple QSAR model on your small target data to predict the activity (e.g., adsorption energy, turnover frequency).

- Conditional Generation: Use this predictor as a guidance signal. During the fine-tuning or generation process, condition the model on a desired property value, or use the predictor's gradient to bias the sampling toward higher-scoring molecules (e.g., via Bayesian optimization or REINFORCE).

Diagram Title: Property-Guided Optimization of Catalyst Generation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Pre-trained Molecular Foundation Model (e.g., ChemBERTa, MoFlow) | Provides a robust, general-purpose initialization of chemical space knowledge, enabling transfer to data-scarce target domains. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Library (e.g., PyTorch Geometric, DGL) | Essential toolkit for implementing and fine-tuning graph-based molecular generators and property predictors. |

| Quantum Chemistry Dataset (e.g., OC20, CatBERTa's source data) | A large-scale source domain dataset for pre-training, containing energy and structure calculations relevant to catalytic surfaces. |

| Differentiable Domain Classifier | A simple neural network used in conjunction with a GRL to quantify and adversarially minimize domain shift during fine-tuning. |

| Molecular Data Augmentation Toolkit (e.g., ChemAugment, SMILES Enumeration) | Software for generating valid, varied representations of a single molecule to artificially expand limited training sets. |

| High-Throughput DFT Calculation Setup (e.g., ASE, GPAW) | Used to generate the small, high-fidelity target domain data for catalyst properties, which is the gold standard for fine-tuning. |

| Reinforcement Learning Framework (e.g., RLlib, custom REINFORCE) | Enables the implementation of property-guided optimization loops for generative models using predictor scores as rewards. |

Data Augmentation Techniques for Expanding the Training Chemical Space

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: After applying SMILES-based randomization, my generative model produces chemically invalid structures. What is the primary cause and solution?

A: The primary cause is the generation of SMILES strings that violate fundamental valence rules or ring syntax during augmentation. To resolve this:

- Implement a Validity Checker: Integrate a rule-based filter (e.g., using RDKit's

Chem.MolFromSmiles) immediately after augmentation to discard any SMILES that fail to parse into a molecule object. - Use Canonicalization: After a valid randomization, canonicalize the SMILES (e.g.,

Chem.MolToSmiles(Chem.MolFromSmiles(smiles))) before adding it to the training set. This ensures a standard representation. - Adopt a Grammar-Based Augmenter: Switch from random string manipulation to using formal molecular grammar systems (like a SMILES grammar) or toolkit-based augmentation (e.g., RDKit's

MolStandardizeorBRICSdecomposition/recombination) which inherently preserve chemical validity.

Q2: My catalyst property predictor performs well on the augmented training set but fails to generalize to real experimental data (domain shift). How can I improve the relevance of my augmented data?

A: This indicates the augmentation technique is expanding the chemical space in directions not aligned with the target domain's data distribution.

- Incorporate Domain-Knowledge Rules: Constrain your augmentation (e.g., fragment swapping, functional group addition) using rules derived from catalytic mechanisms. For example, only allow substitutions at sites known to be peripheral to the active metal center.

- Leverage Unlabeled Target Data: Use a small amount of unlabeled experimental data (target domain) to guide augmentation. Techniques like latent space interpolation between a training molecule and a target domain molecule can generate plausible, domain-relevant intermediates.

- Apply Adversarial Validation: Train a classifier to distinguish between your original/augmented training data and a small set of available target domain data. Use the features most important to this classifier to inform where your augmentation is deficient, and adjust protocols accordingly.

Q3: When using graph-based diffusion for molecule augmentation, the process is computationally expensive and slow for my dataset of 100k molecules. Are there optimization strategies?

A: Yes, computational cost is a known challenge for diffusion models.

- Optimized Sampling Steps: Reduce the number of diffusion sampling steps. Investigate faster sampling schedulers (like DDIM) instead of the default denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM) schedule, which can reduce steps from 1000 to ~50 without severe quality loss.

- Use a Pre-trained Model: Leverage a diffusion model pre-trained on a large, general chemical corpus (e.g., PubChem). Fine-tune this model on your specific catalyst dataset, which requires fewer epochs and steps than training from scratch.

- Batch Processing & Hardware: Ensure you are using GPU acceleration with CUDA and maximize batch sizes within memory limits. Consider using mixed-precision training (

float16) to speed up computations.

Q4: How do I choose between SMILES enumeration, graph deformation, and reaction-based augmentation for my catalyst dataset?

A: The choice depends on your data and goal. See the comparative table below.

| Technique | Core Methodology | Best For Catalyst Space Expansion When... | Key Risk / Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMILES Enumeration | Generating multiple valid string representations of the same molecule. | You have a small dataset of known, stable catalyst molecules and need simple, quick variance. | Does not create new chemical entities; only new representations. Limited impact on domain shift. |

| Graph Deformation | Adding/removing atoms/bonds or perturbing node features via ML models. | You want to explore "nearby" chemical space with smooth interpolations (e.g., varying ligand sizes). | Can generate unrealistic or unstable molecules if not constrained. Computationally intensive. |

| Reaction-Based | Applying known chemical reaction templates (e.g., from USPTO) to reactants. | Your catalyst family is well-described by known synthetic pathways (e.g., cross-coupling ligands). | Heavily dependent on the quality and coverage of the reaction rule set. May produce implausible products. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constrained Molecular Graph Augmentation for Catalyst Ligands

Objective: To generate novel, plausible ligand structures by swapping chemically compatible fragments at specific sites. Materials: RDKit, BRICS module, a dataset of catalyst ligand SMILES. Steps:

- Decomposition: For each ligand molecule in your dataset, apply RDKit's

BRICS.Decomposefunction. This breaks the molecule into fragments at breakable bonds defined by BRICS rules. - Site Identification & Tagging: Identify the fragment that contains the donor atom(s) that bind to the metal center (e.g., nitrogen for bipyridine-like ligands). Label this as the "core anchor" fragment. Tag all other fragments as "peripheral."

- Fragment Library: Compile all unique "peripheral" fragments from your entire dataset into a library, ensuring each is tagged with its BRICS connection points.

- Constrained Recombination: For a given ligand, detach a "peripheral" fragment. From the library, select a new fragment that has compatible BRICS connection points. Recombine it with the "core anchor" using

BRICS.Build. This ensures the donor pharmacophore is preserved. - Validity & Filtering: Check the resulting molecule for chemical validity (RDKit sanitization). Apply optional filters (e.g., molecular weight < 500, synthetic accessibility score).

Protocol 2: Latent Space Interpolation for Domain Bridging

Objective: To generate intermediate molecules that bridge the gap between the training (source) and experimental (target) chemical domains. Materials: A pre-trained molecular variational autoencoder (VAE) or similar model (e.g., JT-VAE), source domain dataset, small set of target domain molecule SMILES. Steps:

- Model Training/Loading: Train or obtain a pre-trained molecular encoder that maps a molecule to a continuous latent vector

z. - Encoding: Encode a representative source domain molecule (

M_source) and a target domain molecule (M_target) into their latent vectorsz_sourceandz_target. - Linear Interpolation: Generate

Nintermediate vectors using linear interpolation:z_i = z_source + (i / N) * (z_target - z_source)fori = 0, 1, ..., N. - Decoding: Decode each

z_iback into a molecular structure using the model's decoder. - Validation & Selection: Filter decoded molecules for chemical validity. Use a domain classifier (see FAQ Q2) or calculate similarity to both source and target to select the most plausible bridging structures for augmentation.

Visualizations

Title: Constrained Fragment Swapping Workflow

Title: Latent Space Interpolation for Domain Bridging

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Augmentation Experiments |

|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit. Core functions include SMILES parsing, molecular graph manipulation, BRICS decomposition, fingerprint generation, and molecular property calculation. Essential for preprocessing, validity checking, and implementing many augmentation rules. |

| PyTor Geometric (PyG) / DGL | Graph neural network (GNN) libraries built on PyTorch/TensorFlow. Required for developing and training graph-based generative models (e.g., GVAEs, Graph Diffusion Models) for advanced, structure-aware molecular augmentation. |

| USPTO Reaction Dataset | A large, publicly available dataset of chemical reactions. Provides the reaction templates necessary for knowledge-based, reaction-driven molecular augmentation, ensuring synthetic plausibility. |

| Molecular Transformer | A sequence-to-sequence model trained on chemical reactions. Can be used to predict products for given reactants, offering a data-driven alternative to rule-based reaction augmentation. |

| SAScore (Synthetic Accessibility Score) | A computational tool to estimate the ease of synthesizing a given molecule. Used as a critical filter post-augmentation to ensure generated catalyst structures are realistically obtainable. |

| CUDA-enabled GPU | Graphics processing unit with parallel computing architecture. Dramatically accelerates the training of deep learning models (e.g., diffusion models, VAEs) used in sophisticated augmentation pipelines. |

Incorporating Physics-Based and Expert Knowledge as Regularization

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My generative model produces catalyst structures that are chemically valid but physically implausible (e.g., unstable bond lengths, unrealistic angles). How can I regularize the output? A: Implement a Physics-Based Loss Regularization. Add a penalty term to your training loss that quantifies deviation from known physical laws.

- Protocol: For a generated catalyst structure with atomic coordinates, calculate its potential energy using a classical force field (e.g., UFF, MMFF94) or a fast, learned interatomic potential. Define the regularization term as

L_physics = λ * Energy, whereλis a tunable hyperparameter. This penalizes high-energy, unstable configurations. - Example Table: Effect of Physics Regularization on Generated Structures

Model Variant Avg. Generated Structure Energy (eV) % Plausible Bond Lengths DFT-Validated Stability Score Base VAE 15.7 ± 4.2 67% 0.41 + Physics Loss (λ=0.1) 5.2 ± 1.8 92% 0.78 + Physics Loss (λ=0.5) 3.1 ± 0.9 98% 0.85

Q2: When facing domain shift to a new reaction condition (e.g., high pressure), my model performance degrades. How can expert knowledge help? A: Use Expert Rules as a Constraint Layer. Incorproate known structure-activity relationships (SAR) or synthetic accessibility rules as a post-generation filter or an in-process guidance mechanism.

- Protocol: Define a set of allowable ranges for molecular descriptors (e.g., oxidation state of active metal, coordination number) based on literature and expert input. After generation, reject any candidate not meeting all rules. For iterative models, use these rules to bias the sampling process.

- Key Research Reagent Solutions:

Item Function in Regularization Context RDKit Cheminformatics toolkit for calculating molecular descriptors (e.g., ring counts, logP) to enforce expert rules. pymatgen Python library for analyzing materials, essential for computing catalyst descriptors like bulk modulus or surface energy. ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) Used to set up and run the fast force field calculations for physics-based energy evaluation. Custom Rule Set (YAML/JSON) A human-readable file storing expert-defined constraints (e.g., "max_oxidation_state_Fe": 3) for model integration.

Q3: How do I balance the data-driven loss with the new physics/expert regularization terms? A: Perform a Hyperparameter Sensitivity Grid Search. The weighting coefficients (λ) are critical.

- Protocol: Train multiple model instances with different combinations of regularization weights. Use a small, held-out validation set from the target domain (if available) or a domain-shift simulation set to evaluate performance. Monitor both primary metrics (e.g., activity prediction error) and regularization-specific metrics (e.g., energy, rule violation count).

- Example Table: Hyperparameter Tuning for Regularization Balance

λphysics λexpert Target Domain MAE Rule Violation Rate Avg. Energy 0.0 0.0 1.45 34% 18.5 0.05 0.5 1.21 12% 9.8 0.1 1.0 1.08 5% 6.2 0.5 2.0 1.32 2% 4.1

Q4: I have limited labeled data in the new target domain. Can these regularization methods help? A: Yes, they act as a form of transfer learning. Physics and expert knowledge are often domain-invariant. By strongly regularizing with them, you constrain the model to a plausible solution space, reducing overfitting to small target data.

- Protocol: Pre-train your generative model on a large source dataset with the regularization terms. Fine-tune on the small target dataset, potentially with increased regularization weights to prevent catastrophic forgetting of the physical/expert constraints.

Experimental Protocol: Validating Regularization Efficacy Against Domain Shift

Objective: Assess if physics/expert regularization improves the robustness of a catalyst property predictor when applied to a new thermodynamic condition.

- Data Splitting: Split catalyst dataset into Source Domain (e.g., reactions at 300K, 1 atm) and Target Domain (e.g., reactions at 500K, 10 atm).

- Model Training: Train three graph neural network (GNN) models:

- Base Model: Trained on source data with standard MSE loss.

- Regularized Model: Trained on source data with MSE loss +

λ_physics*Energy+λ_expert*Rule_Violations. - Target Model (Oracle): Trained on target data (for reference).

- Domain Shift Evaluation: Apply all models to the held-out target domain test set. Evaluate prediction error (MAE) for target property (e.g., activation energy).

- Analysis: Compare MAE of Base vs. Regularized Model. Perform ablation studies on each regularization term.

Diagram Title: Protocol to Test Regularization Against Domain Shift

Diagram Title: Regularization Integration in a Generative Model Pipeline

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Q1: During the high-throughput screening cycle, our generative model fails to propose catalyst candidates outside the narrow property space of the initial training data. How can we encourage more diverse exploration to address domain shift? A: This is a classic symptom of model overfitting and poor exploration-exploitation balance. Implement a Thompson Sampling or Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) strategy within your acquisition function instead of standard expected improvement. Additionally, inject a small percentage (e.g., 5%) of purely random candidates into each batch to probe unseen areas of the chemical space. Ensure your model's latent space is regularized (e.g., using a β-VAE loss) to improve smoothness and generalizability.

Q2: The automated characterization data (e.g., Turnover Frequency from HTE) we feed back into the loop has high variance, leading to noisy model updates. How should we preprocess this data? A: Implement a robust data cleaning pipeline before the model update step. Key steps include:

- Statistical Outlier Removal: Apply the Interquartile Range (IQR) method for each experimental condition.

- Replicate Aggregation: Use the median value of technical replicates, not the mean.

- Uncertainty Quantification: Pass the measurement standard deviation as an explicit weight to the model during training. The following table summarizes a recommended protocol:

| Step | Action | Parameter / Metric |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Replicate Check | Flag runs with fewer than N replicates (N=3 recommended). | Success Flag (Boolean) |

| 2. Outlier Filter | Remove data points outside Q1 - 1.5IQR and Q3 + 1.5IQR. | IQR Threshold = 1.5 |

| 3. Data Aggregation | Calculate median and MAD (Median Absolute Deviation) of replicates. | Value = Median; Uncertainty = MAD |

| 4. Model Update Weight | Use inverse uncertainty squared as sample weight in loss function. | Weight = 1 / (MAD² + ε) |

Q3: Our iterative loop seems to get "stuck" in a local optimum, continually proposing similar catalyst structures. What loop configuration parameters should we adjust? A: This indicates insufficient exploration. Adjust the following parameters in your active learning controller:

- Increase the diversity penalty in your batch acquisition function (e.g., increase the λ coefficient in a batch greedy algorithm).

- Reduce the trust in model predictions for regions far from training data by implementing a dynamic uncertainty threshold. Reject candidates where the model's epistemic uncertainty is below a certain percentile, forcing characterization of more uncertain samples.

- Periodically retrain the model from scratch using the entire accumulated dataset, rather than performing continuous fine-tuning, to help escape pathological parameter states.

Q4: How do we validate that the model is actually adapting to domain shift and not just memorizing new data? A: Establish a rigorous, held-out temporal validation set. Reserve a portion (~10%) of catalysts synthesized in later cycles as a never-before-seen test set. Monitor two key metrics over cycles:

- Performance on Initial Test Set: Should decrease, indicating domain shift away from the original space.

- Performance on Temporal Hold-Out Set: Should increase, indicating successful adaptation to the new domain. The protocol is detailed below:

Protocol: Temporal Validation for Domain Shift Assessment

- Data Splitting: After each full cycle of experimentation (e.g., every 200 new catalysts), randomly select 10% of the newly acquired data points and place them in the Temporal Hold-Out Set. Do not use this set for training.

- Model Training: Train your primary model on the Training Set (all prior data not in hold-out sets).

- Validation & Metrics: Calculate the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) on both the Initial Static Test Set (from cycle 0) and the cumulative Temporal Hold-Out Set.

- Trend Analysis: Plot these MAE values versus active learning cycle number. Successful adaptation is shown by a rising line for the Initial Set and a falling line for the Temporal Set.

Q5: What is the recommended software architecture to manage data flow between the generative model, HTE platform, and characterization databases? A: A modular, microservices architecture is essential. See the workflow diagram below.

Active Learning Loop Architecture for Catalyst Discovery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Active Learning Loop for Catalysis |

|---|---|

| High-Throughput Parallel Reactor | Enables simultaneous synthesis or testing of hundreds of catalyst candidates (e.g., in 96-well plate format) under controlled conditions, generating the primary data for the loop. |

| Automated Liquid Handling Robot | Precisely dispenses precursor solutions, ligands, and substrates for reproducible catalyst preparation and reaction initiation in the HTE platform. |

| In-Line GC/MS or HPLC | Provides rapid, automated quantitative analysis of reaction yields and selectivity from micro-scale HTE reactions, essential for feedback data. |

| Cheminformatics Software Suite (e.g., RDKit) | Generates molecular descriptors (fingerprints, Morgan fingerprints), handles SMILES strings, and calculates basic molecular properties for featurizing catalyst structures. |

| Active Learning Library (e.g., Ax, BoTorch, DeepChem) | Provides algorithms for Bayesian optimization, acquisition functions (EI, UCB), and management of the experiment-model loop. |

| Cloud/Lab Data Lake | Centralized, versioned storage for all raw instrument data, processed results, and model checkpoints, ensuring reproducibility and traceability. |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: After fine-tuning a generative model on a proprietary catalyst dataset, the inference speed in our high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS) pipeline has dropped by 70%. What are the primary causes and solutions? A1: This is a common deployment bottleneck. Primary causes include: 1) Increased model complexity from adaptation layers, 2) Suboptimal serialization/deserialization of the adapted model weights, 3) Lack of hardware-aware graph optimization for the new architecture. Solutions involve profiling the model with tools like PyTorch Profiler, applying graph optimization (e.g., TorchScript, ONNX runtime conversion), and implementing model quantization (FP16/INT8) if precision loss is acceptable for the screening stage.

Q2: Our domain-adapted model performs well on internal validation sets but fails to generate chemically valid structures when deployed in the generative pipeline. How do we debug this? A2: This indicates a potential domain shift in the output constraint mechanisms. Follow this protocol:

- Isolate the Decoder: Run the adapted model's decoder separately with latent vectors from the pre-trained model to check if the issue is in the encoding or decoding step.

- Validity Checker Integration: Ensure the chemical validity checker (e.g., RDKit's

SanitizeMol) is correctly integrated post-generation. The adaptation may have altered the token/probability distribution, requiring adjusted post-processing thresholds. - Latent Space Audit: Perform a t-SNE visualization comparing latent vectors of valid vs. invalid generated molecules to identify cluster disparities.

Q3: We observe "catastrophic forgetting" of general chemical knowledge when deploying our catalyst-specific adapted model, leading to poor diversity in generated candidates. How can this be mitigated in the deployment framework? A3: This requires implementing deployment strategies that balance specialization and generalization.

- Solution A: Model Ensemble Deployment: Deploy both the base pre-trained model and the adapted model in parallel. Use a router that directs queries based on novelty scores derived from the input query's latent space distance to the catalyst domain.

- Solution B: Elastic Weight Consolidation (EWC) at Inference: Integrate an EWC-inspired penalty term during inference scoring to penalize generations that deviate strongly from the base model's important parameters. This requires configuring the serving API to apply this constrained scoring.

Q4: During A/B testing of a new adapted model in the live pipeline, how do we ensure consistent and reproducible molecule generation for identical seed inputs? A4: Reproducibility is critical for validation. Implement the following in your deployment container:

- Seed Locking: Enforce deterministic algorithms by setting all random seeds (Python, NumPy, PyTorch, CUDA) at the start of each inference call.

- Containerized Environment: Use a Docker container with frozen library versions (PyTorch, CUDA toolkit) for model serving.

- Versioned Artifacts: Log the exact model artifact hash, preprocessing script version, and inference configuration (batch size, sampling temperature) with every generated batch.

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Steps

Protocol: Deployed Model Latent Space Drift Measurement Objective: Quantify the shift in the latent space representation of the core molecular structures between the pre-trained and deployed adapted model. Method:

- Input: A standardized benchmark set of 1000 diverse drug-like molecules (e.g., from ZINC).

- Process: Encode each molecule using both the pre-trained and the adapted model's encoder.

- Analysis: Calculate the Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Cosine Similarity for each molecule's latent vector pair. Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to visualize the collective drift.

- Threshold: A mean cosine similarity of <0.85 across the set indicates significant drift requiring investigation.

Protocol: Throughput and Latency Benchmarking for Deployment Objective: Establish performance baselines for the integrated model within the pipeline. Method:

- Test Environment: Isolate the model serving instance (e.g., a dedicated GPU VM with TorchServe or Triton Inference Server).

- Workload: Simulate load with a representative dataset of 10,000 catalyst query scaffolds. Measure Time-to-First-Token (TTFT) and Time-Per-Output-Token (TPOT) for generative models, or total inference time for predictive models.

- Metrics: Record P95 latency, throughput (molecules/sec), and GPU memory utilization under concurrent request loads (e.g., 1, 10, 50 concurrent clients). Compare against pre-deployment benchmarks.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Model Integration Methods

| Integration Method | Avg. Inference Latency (ms) | Throughput (mols/sec) | Validity Rate (%) | Novelty (Tanimoto <0.4) | Required Deployment Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monolithic Adapted Model | 450 | 220 | 95.2 | 65.3 | High |

| API-Routed Ensemble | 320 | 180 | 98.7 | 58.1 | Very High |

| Quantized (INT8) Adapted Model | 120 | 510 | 94.1 | 64.8 | Medium |

| Base Pre-trained Model Only | 100 | 600 | 99.9 | 85.0 | Low |

Table 2: Common Deployment Errors and Resolutions

| Error Code / Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Diagnostic Step | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

CUDA OOM at Inference |

Adapted model graph not optimized for target GPU memory; batch size too high. | Run nvidia-smi to monitor memory allocation. |

Implement dynamic batching in the inference server; convert model to half-precision (FP16). |

Invalid SMILES Output |

Tokenizer vocabulary mismatch between training and serving environments. | Compare tokenizer .json files' MD5 hashes. |

Enforce tokenizer version consistency via containerization. |

High API Latency Variance |

Resource contention in Kubernetes pod; inefficient model warm-up. | Check node CPU/GPU load averages during inference. | Configure readiness/liveness probes with load-based delays; implement pre-warming of model graphs. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Deployment & Validation |

|---|---|

| TorchServe / Triton Inference Server | Industry-standard model serving frameworks that provide batching, scaling, and monitoring APIs for production deployment. |

| ONNX Runtime | Cross-platform inference accelerator that can optimize and run models exported from PyTorch/TensorFlow, often improving latency. |

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit used for post-generation molecule sanitization, validity checking, and descriptor calculation. |

| Weights & Biases (W&B) / MLflow | MLOps platforms for tracking model versions, artifacts, and inference performance metrics post-deployment. |

| Docker & Kubernetes | Containerization and orchestration tools to create reproducible, scalable environments for model deployment across clusters. |

| Molecular Sets (MOSES) | Benchmarking platform providing standardized metrics (e.g., validity, uniqueness, novelty) to evaluate deployed generative model output. |

Workflow & System Diagrams

Title: Model Adaptation and Deployment Workflow

Title: Inference Routing Logic for Model Deployment

Diagnosing and Fixing Domain Shift: A Troubleshooting Playbook for Researchers

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During our catalyst screening, the generative model's predictions are increasingly inaccurate. What are the first metrics to check for domain shift?

A: Immediately check the following quantitative descriptors of your experimental data distribution against the model's training data:

- Feature Space Mean/SD: Calculate the mean and standard deviation of key molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, logP, polar surface area) for your new batch of candidate catalysts and compare them to the training set.

- Prediction Confidence Drift: Monitor the model's average prediction entropy or confidence scores for new inputs. A steady increase in entropy or decrease in confidence suggests unfamiliar chemical space.

- t-SNE/UMAP Overlap: Perform a dimensionality reduction visualization. Lack of overlap between new data points and the training cloud is a visual red flag.

Q2: What is a definitive statistical test to confirm domain shift in our high-throughput experimentation (HTE) data before proceeding to validation?

A: The Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) test is a robust, kernel-based statistical test for comparing two distributions. A significant p-value (<0.05) indicates a detected shift.

Protocol: MMD Test for Catalyst Data

- Inputs: Feature vectors from the training set (T) and the new experimental batch (E).

- Feature Extraction: Use standardized RDKit or Mordred descriptors for all molecules in both sets.

- Implementation: Use the PyTorch or sklearn MMD implementation with a Gaussian kernel.

- Permutation Test: To obtain a p-value, perform permutation testing (e.g., 1000 permutations) by shuffling the labels of T and E and recomputing MMD each time.

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics for Domain Shift Detection

| Metric | Calculation Tool | Threshold for Concern | Interpretation for Catalyst Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Mean Shift | RDKit, Pandas | >2 SD from training mean | New catalysts have fundamentally different physicochemical properties. |

| Prediction Entropy | Model's softmax output | Steady upward trend over batches | Model is increasingly uncertain, likely due to novel scaffolds. |

| Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) | sklearn, torch |

p-value < 0.05 | Statistical evidence that data distributions are different. |

| Kullback-Leibler Divergence | scipy.stats.entropy |

Value > 0.3 | Significant divergence in the probability distribution of key features. |

Q3: We suspect a "silent" shift where catalyst structures look similar but performance fails. How can we detect this?

A: This often involves a shift in the conditional distribution P(y|x). Implement the following protocol for Classifier Two-Sample Testing (C2ST).

Protocol: C2ST for Silent Shift Detection

- Labeling: Label your training data as

0and new experimental data as1. - Train a Discriminator: Train a binary classifier (e.g., a small neural network or XGBoost) to distinguish between the two sets, using the molecular descriptors and the generative model's predicted performance scores as features.

- Evaluate: If the classifier can distinguish the sets with high accuracy (e.g., >70%), a silent shift is likely present. The classifier's feature importance reveals which latent factors are shifting.

Title: C2ST Protocol for Silent Domain Shift Detection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents & Tools for Domain Shift Analysis

| Item | Function in Detection Protocols |

|---|---|

| RDKit or Mordred | Open-source cheminformatics libraries for calculating standardized molecular descriptors from catalyst structures. |

| scikit-learn (sklearn) | Python library providing implementations for t-SNE/UMAP, MMD basics, and classifier models for C2ST. |

| PyTorch / TensorFlow | Deep learning frameworks essential for building custom discriminators and implementing advanced MMD tests. |

| Chemprop or DGL-LifeSci | Specialized graph neural network libraries for directly learning on molecular graphs, capturing subtle structural shifts. |

| Benchmark Catalyst Set | A small, well-characterized set of catalysts with known performance, used as a constant reference to calibrate experiments. |

Q4: What is a practical weekly monitoring workflow to catch domain shift early in a long-term project?

A: Implement a automated monitoring pipeline as diagrammed below.

Title: Weekly Domain Shift Monitoring Workflow

Hyperparameter Optimization for Improved Out-of-Domain Generalization

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My generative model collapses to producing similar catalyst structures regardless of the input domain descriptor. Which hyperparameters should I prioritize tuning? A: This mode collapse is often linked to the adversarial training balance and latent space regularization. Prioritize tuning:

- Generator Loss Coefficient (λ_gen): Start with a lower value (e.g., 0.1) and increase incrementally to strengthen the generator's signal against the discriminator.

- Gradient Penalty Weight (λ_gp): For WGAN-GP architectures, values between 5.0 and 10.0 are typical. Insufficient penalty leads to unstable training.

- Latent Vector Dimension (z_dim): An overly small dimension (e.g., < 50) restricts expressiveness. Try increasing it to 128 or 256.

- Examine the discriminator's accuracy. If it reaches 100% too quickly, it's overpowering the generator. Adjust learning rates or architecture.

Q2: During out-of-domain testing, my model generates chemically invalid or unstable catalyst structures. How can hyperparameter optimization address this? A: This indicates a failure in incorporating domain knowledge. Focus on constraint-enforcement hyperparameters:

- Validity Regularization Weight (λ_val): This coefficient scales penalty terms for violating chemical rules (e.g., valency). Systematically increase it from 0.01 to 0.5 and monitor the valid fraction output.

- Reconstruction Loss Weight (β in β-VAE frameworks): A higher β (e.g., > 1.0) strengthens the latent bottleneck, potentially forcing the learning of more fundamental, domain-invariant chemical rules at the cost of detail.

- Fine-tuning Learning Rate: When fine-tuning a pre-trained model on a new domain, use a learning rate 1-2 orders of magnitude smaller than the pre-training rate to avoid catastrophic forgetting of underlying chemistry.

Q3: My model's performance degrades significantly on domains with scarce data. What Bayesian Optimization (BO) settings are most effective for this low-data regime? A: In low-data scenarios, the choice of BO acquisition function and prior is critical.

- Acquisition Function: Use Expected Improvement per Second (EIps) or Noisy Expected Improvement instead of standard Expected Improvement. They are more sample-efficient and account for evaluation noise.

- Initial Design of Experiments (DoE): Allocate a higher proportion of your budget to the initial random sampling (e.g., 30% instead of 10%) to build a better surrogate model.

- Kernel Selection: For categorical hyperparameters (e.g., activation function type), use a Matérn 5/2 kernel with automatic relevance determination (ARD). It handles non-stationarity better than the standard squared-exponential kernel in mixed search spaces.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Cross-Domain Validation for Hyperparameter Search This protocol is designed to evaluate hyperparameter sets for out-of-domain robustness.

- Data Partitioning: Split your multi-domain dataset into source domains (Dsrc) and a held-out *target domain* (Dtgt). D_tgt should simulate a novel application space.

- Training: Train the catalyst generative model only on D_src using a candidate hyperparameter set.

- Evaluation: Generate candidate structures for the specific task in D_tgt. Evaluate them using the primary metric (e.g., predicted catalytic activity via a surrogate model).

- Search Loop: Use a Bayesian Optimization (BO) loop to propose new hyperparameter sets, aiming to maximize the performance on Dtgt. The key is that Dtgt is never used for training, only for guiding the hyperparameter search.

- Final Assessment: The optimal hyperparameters found are used to train a final model on all available source data. Its generalization is tested on completely unseen test domains.

Protocol 2: Hyperparameter Ablation for Domain-Invariant Feature Learning This protocol isolates the effect of regularization hyperparameters.

- Baseline Model: Train a standard generative adversarial network (GAN) with default hyperparameters on a mixed domain dataset.

- Intervention: Introduce a domain-adversarial regularization term (λ_dann) to the generator's objective, aiming to learn domain-invariant features in the latent space.

- Controlled Experiment: Perform a 1-dimensional ablation: vary λ_dann across a logarithmic scale (e.g., [0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1.0, 10.0]) while keeping all other hyperparameters fixed.

- Measurement: For each λ_dann value, measure: (a) Domain Classification Accuracy (lower is better for invariance), and (b) Task Performance (e.g., average predicted turnover frequency) on a validation set containing all domains.

- Analysis: Plot the Pareto frontier to identify the λ_dann value that best balances domain invariance with task-specific performance.

Table 1: Impact of Latent Dimension (z_dim) on Out-of-Domain Validity and Diversity

| z_dim | In-Domain Validity (%) | Out-of-Domain Validity (%) | In-Domain Diversity (↑) | Out-of-Domain Diversity (↑) | Training Time (Epochs to Converge) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32 | 98.5 | 65.2 | 0.78 | 0.41 | 120 |

| 64 | 99.1 | 78.7 | 0.85 | 0.62 | 150 |

| 128 | 99.3 | 89.5 | 0.88 | 0.79 | 200 |

| 256 | 99.5 | 88.1 | 0.87 | 0.77 | 280 |

Diversity measured using average Tanimoto dissimilarity between generated structures. Out-of-Domain testing was performed on a perovskite catalyst dataset after training on metal-organic frameworks.

Table 2: Bayesian Optimization Results for Low-Data Target Domain

| Acquisition Function | Initial DoE Points | Optimal λ_val Found | Optimal β (VAE) Found | Target Domain Performance (TOF↑) | BO Iterations to Converge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected Improvement | 10 (10%) | 0.12 | 0.85 | 12.4 | 45 |

| Probability of Imp. | 10 (10%) | 0.08 | 1.12 | 14.1 | 50 |

| Noisy EI | 30 (30%) | 0.31 | 1.45 | 18.7 | 35 |

| EI per Second | 30 (30%) | 0.28 | 1.38 | 17.9 | 32 |

Total BO budget was 100 evaluations. Target domain had only 50 training samples. Performance measured by predicted Turnover Frequency (TOF) from a pre-trained property predictor.

Diagrams

Title: HPO Workflow for OOD Generalization

Title: Domain-Adversarial Regularization Path

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function in Hyperparameter Optimization for OOD |

|---|---|

| Ray Tune | A scalable Python library for distributed hyperparameter tuning. Supports advanced schedulers (ASHA, HyperBand) and seamless integration with ML frameworks, crucial for large-scale catalyst generation experiments. |

| BoTorch | A Bayesian optimization library built on PyTorch. Essential for defining custom acquisition functions (like Noisy EI) and handling mixed search spaces (continuous and categorical HPs) common in model architecture selection. |

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit. Used to calculate chemical validity metrics and structure-based fingerprints, which serve as critical evaluation functions during the HPO loop for out-of-domain generation quality. |

| DomainBed | An empirical framework for domain generalization research. Provides standardized dataset splits and evaluation protocols to rigorously test if HPO leads to true OOD improvement versus hidden target leakage. |

| Weights & Biases (W&B) / MLflow | Experiment tracking platforms. Vital for logging HPO trials, visualizing the effect of hyperparameters across different domains, and maintaining reproducibility in the iterative research process. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in Multi-Task & Foundational Model Pipelines

Q1: My multi-task model exhibits catastrophic forgetting; performance on the primary catalyst property prediction task degrades when auxiliary tasks are added. How can I mitigate this?

A: This is a common issue when task gradients conflict. Implement one or more of the following protocols:

- Experimental Protocol: Gradient Surgery (PCGrad)

- For each task t, compute the gradient gt of its loss.

- For each task pair (i, j), project the gradient gi onto the normal plane of gj if their dot product is negative: gi = gi - (gi · gj / ||gj||²) * g_j.

- Update the shared model parameters using the sum of the conflict-regularized gradients.

- Experimental Protocol: Uncertainty-Weighted Loss (Kendall et al., 2018)

- Model the homoscedastic uncertainty σt for each task t as a learnable parameter.

- Modify the total loss to: Ltotal = Σt (1/(2σt²) Lt + log σt).

- This allows the model to dynamically down-weight noisy or conflicting tasks during training.

Q2: When fine-tuning a pre-trained molecular foundational model (e.g., on a small, proprietary catalyst dataset), the model overfits rapidly. What strategies are effective?

A: Overfitting indicates the fine-tuning signal is overwhelming the pre-trained knowledge. Use strong regularization.

- Experimental Protocol: Layer-wise Learning Rate Decay (LLRD)

- Assign lower learning rates to layers closer to the input (pre-trained layers).

- For a model with N layers, fine-tuning learning rate λ, and decay factor d, set LR for layer k as: λ_k = λ * d^(N-k).

- Typical values: λ=1e-4, d=0.95. This gently adapts pre-trained features without erasing them.

- Experimental Protocol: Linear Probing then Fine-Tuning

- Freeze all backbone layers of the pre-trained model.

- Train only the newly attached task-specific prediction head on your target data for a full set of epochs.

- Unfreeze the backbone and conduct full model fine-tuning for a small number of epochs with a very low learning rate (e.g., 1e-5).