Rational Catalyst Design and Synthesis: Principles, Strategies, and Applications in Sustainable Chemistry

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the modern principles of rational catalyst design, a paradigm shift from traditional trial-and-error approaches.

Rational Catalyst Design and Synthesis: Principles, Strategies, and Applications in Sustainable Chemistry

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the modern principles of rational catalyst design, a paradigm shift from traditional trial-and-error approaches. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores foundational concepts including electronic structure modulation and active site engineering. The scope extends to advanced methodological applications in key reactions like CO2 hydrogenation and nitro compound reduction, troubleshooting common stability and selectivity challenges, and the critical role of AI and machine learning in high-throughput validation. By integrating foundational science with cutting-edge computational and experimental validation techniques, this review serves as a strategic guide for developing high-performance, sustainable catalysts for biomedical and industrial applications.

Deconstructing the Catalyst Blueprint: From Atomic Structure to Interfacial Microenvironments

Rational design represents a paradigm shift in scientific research and development, moving from traditional trial-and-error approaches to mechanism-driven strategies informed by fundamental principles. This methodology leverages deep understanding of underlying mechanisms—whether in chemical reactions, biological systems, or material properties—to deliberately engineer solutions with predictable outcomes. In the context of catalyst design and synthesis research, rational approaches utilize computational modeling, advanced characterization techniques, and systematic design principles to accelerate discovery and optimization processes while reducing resource expenditure.

The framework of rational design relies on establishing clear structure-function relationships that enable researchers to manipulate system components with precision. By understanding how molecular structure influences catalytic activity, selectivity, and stability, scientists can propose targeted modifications rather than relying on exhaustive experimental screening. This approach has transformed multiple fields, including heterogeneous catalysis, pharmaceutical development, and genome engineering, where traditional methods often proved inefficient and time-consuming.

Fundamental Principles of Rational Design

Mechanism-Driven Development

At the core of rational design lies the principle of mechanism-driven development, which requires comprehensive understanding of the fundamental processes governing system behavior. In catalyst design, this involves elucidating reaction pathways, identifying rate-determining steps, and characterizing key intermediates that influence overall efficiency [1]. For electrocatalytic reduction of nitrogen oxides (NOx), for instance, mechanistic insights reveal how catalyst surface properties affect the binding energies of intermediates such as *NO, *N, and *NH, which ultimately determine selectivity toward ammonia production versus competing reactions [1].

Mechanistic understanding enables researchers to identify descriptors that correlate with performance metrics. These descriptors—which may include adsorption energies, d-band centers, or structural parameters—serve as quantitative indicators for predicting catalyst behavior before synthesis. Computational studies have demonstrated that the nitrogen binding energy serves as a crucial descriptor for NOx electroreduction, with optimal values balancing intermediate stabilization without poisoning the catalyst surface [2]. Such descriptors provide guiding principles for targeted material design rather than random exploration.

Integration of Computational and Experimental Methods

Rational design thrives on the synergistic integration of computational modeling and experimental validation. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations provide atomic-level insights into reaction mechanisms and active site properties, while microkinetic modeling bridges elementary steps with macroscopic performance [1]. This computational guidance significantly narrows the candidate space for experimental investigation, focusing resources on the most promising materials.

Recent advances have incorporated machine learning algorithms that identify complex patterns in high-dimensional data, further accelerating the discovery process [1]. These data-driven approaches can map composition-structure-property relationships with minimal prior assumptions, complementing physics-based models. The emerging synergy between theory and experiment has enabled data-driven catalyst discovery and mechanism-guided design, particularly for complex reactions like NOx electroreduction where multiple pathways compete [1].

Rational Design in Catalyst Development

Computational Approaches in Catalyst Design

Computational methods form the backbone of rational catalyst design, providing insights difficult to obtain through experimental techniques alone. First-principles calculations based on density functional theory (DFT) enable researchers to model surface reactions, predict intermediate stability, and calculate activation barriers for elementary steps [1]. These theoretical approaches have uncovered fundamental principles governing NOx electroreduction, including the competing reaction networks that dictate selectivity toward ammonia versus other products like N2 or N2O [2].

Microkinetic modeling extends beyond DFT by simulating the overall reaction rate and selectivity based on calculated parameters for individual steps. This multi-scale approach bridges the gap between quantum-level calculations and experimental observables, enabling prediction of catalytic performance under realistic conditions [1]. For NOx reduction, microkinetic analyses have revealed how operational parameters (potential, pH, concentration) influence the dominant reaction pathway and product distribution.

Advanced computational techniques now include high-throughput screening of material libraries, where thousands of candidate catalysts are evaluated virtually before laboratory synthesis. This approach has identified promising compositions for NOx reduction that might have been overlooked through conventional methods [1]. When combined with machine learning, these virtual screenings can navigate complex material spaces more efficiently than human intuition alone.

Descriptor-Based Catalyst Optimization

Descriptor-based approaches represent a powerful strategy in rational catalyst design, where easily computable or measurable parameters correlate with catalytic performance. These activity descriptors serve as proxies for more complex properties, enabling rapid assessment of material potential. For NOx electroreduction, key descriptors include:

- Nitrogen binding energy: Correlates with the stability of key intermediates like *N and *NH

- Oxophilicity: Influences catalyst susceptibility to oxidation and deactivation

- d-band center: Predicts adsorption strength of reaction intermediates on transition metal surfaces

Table 1: Key Descriptors for Rational Catalyst Design in NOx Electroreduction

| Descriptor | Correlation with Activity | Computational Method | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen Binding Energy | Volcano relationship with NH3 formation rate | DFT calculations | Electrochemical testing with in-situ spectroscopy |

| d-band Center | Determines intermediate adsorption strength | Electronic structure calculations | X-ray absorption spectroscopy |

| Surface Charge Density | Affects potential-dependent steps | Poisson-Boltzmann calculations | Impedance spectroscopy |

| Work Function | Correlates with electron transfer efficiency | Surface calculations | Kelvin probe measurements |

By optimizing these descriptors, researchers can systematically improve catalyst performance. For instance, engineering strained metal surfaces or alloying elements can tune the d-band center to achieve optimal binding of NOx intermediates [1]. Similarly, introducing oxygen vacancies in metal oxide supports can enhance catalyst oxophilicity, promoting nitrate activation while maintaining stability under operating conditions [2].

Rational Design in Pharmaceutical Development

Molecular Glue Degraders

Rational design has revolutionized pharmaceutical development, particularly in the emerging field of targeted protein degradation. Traditional drug discovery often relied on screening large compound libraries to identify inhibitors that block protein function. In contrast, rational approaches enable the mechanism-guided design of molecular glue degraders that induce interactions between target proteins and cellular degradation machinery [3].

The rational design of molecular glues involves appending chemical gluing moieties to established small molecule inhibitors, transforming them into degraders without requiring specific E3 ubiquitin ligase recruiters [3]. This approach was successfully demonstrated for cyclin-dependent kinase 12 and 13 (CDK12/13) dual inhibitors, where incorporating a hydrophobic aromatic ring or double bond enabled recruitment of DNA damage-binding protein 1 (DDB1), creating potent monovalent molecular glue degraders [3].

Similarly, attaching cysteine-reactive warheads to bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) inhibitors converted them into degraders by recruiting the DDB1 and CUL4-associated factor 16 (DCAF16) E3 ligase complex [3]. This rational strategy represents a significant advancement over traditional serendipitous discovery methods, offering a systematic approach to designing degraders with predictable properties.

Experimental Protocols for Molecular Glue Development

The development of molecular glue degraders follows a structured protocol that integrates computational design with experimental validation:

- Target Analysis: Identify surface features and binding pockets on the protein of interest using crystallographic data and molecular modeling.

- Gluing Moiety Selection: Choose appropriate chemical groups (hydrophobic patches, reactive warheads) that can potentially recruit E3 ligase complexes.

- Linker Optimization: Design chemical linkers of appropriate length and flexibility to connect the inhibitor with the gluing moiety without disrupting binding.

- Synthesis and Characterization: Prepare candidate compounds using iterative medicinal chemistry approaches.

- Cellular Activity Assessment: Evaluate degradation efficiency, selectivity, and potency in relevant cell lines.

- Mechanistic Validation: Confirm engagement with the ubiquitin-proteasome system through counter-screens with proteasome inhibitors and E3 ligase knockdown.

This protocol emphasizes the importance of structure-based design throughout the development process, with each iteration informed by structural insights and mechanistic understanding.

Rational Design in Genome Engineering

Reverse Prime Editing (rPE) Systems

Rational design principles have propelled advances in genome editing technologies, particularly in developing precision editing tools with expanded capabilities. The recent creation of reverse prime editing (rPE) systems exemplifies how mechanistic understanding can drive technological innovation [4]. Traditional prime editing was limited to DNA modifications at the 3' direction of the RuvC-mediated nick site, constraining its application scope.

Through rational engineering of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, researchers developed rPE by converting Cas9-H840A to Cas9-D10A and redesigning the pegRNA to bind the DNA sequence adjacent to the 5' terminus of the HNH-mediated nick site [4]. This inverse design achieved a reverse editing window while potentially enhancing fidelity, as Cas9-D10A produces fewer unwanted double-strand breaks compared to Cas9-H840A [4].

The rPE system demonstrated substantial editing efficiency (up to 16.34%) across multiple genomic loci in human cells [4]. Further optimization through protein engineering using protein language models yielded enhanced variants (erPEmax and erPE7max) achieving editing efficiencies up to 44.41% without requiring additional gRNAs or positive selection [4]. This rational approach to expanding editing scope highlights how mechanistic insights can overcome limitations of existing technologies.

Workflow for rPE Implementation

The implementation of reverse prime editing follows a meticulously designed workflow that ensures precise genomic modifications:

Diagram 1: rPE Workflow

This workflow emphasizes the importance of rpegRNA design, with primer binding site (PBS) and reverse transcriptase template (RTT) lengths optimized between 10-16 nucleotides for maximum efficiency [4]. The system's versatility was demonstrated across multiple cell lines (HEK293T, HeLa, HepG2) and genomic loci, confirming its broad applicability for research and therapeutic purposes [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Rational design methodologies rely on specialized reagents and tools that enable precise manipulation of molecular systems. The following table summarizes essential research reagents used in the featured applications of rational design:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Rational Design Applications

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) Software | Computational modeling of electronic structure and reaction mechanisms | Catalyst screening; Reaction pathway analysis | First-principles calculations; Periodic boundary conditions |

| Reverse Prime Editor (rPE) Components | Precision genome editing beyond RuvC-nick site limitations | Therapeutic mutation correction; Gene insertion | Cas9-D10A nickase; Engineered reverse transcriptase; rpegRNA |

| Molecular Glue Degraders | Induce targeted protein degradation via ubiquitin-proteasome system | Oncology; Neurological disorders | Bifunctional compounds; E3 ligase recruiters |

| Microkinetic Modeling Software | Simulate reaction rates and selectivity from elementary steps | Catalyst optimization; Process condition screening | Multi-scale approach; DFT parameter integration |

| Protein Language Models | AI-driven protein engineering and optimization | Reverse transcriptase enhancement; Cas9 variants | Pattern recognition in protein sequences; Fitness prediction |

| (S,R,S)-Ahpc-peg3-NH2 | (S,R,S)-Ahpc-peg3-NH2, MF:C30H45N5O7S, MW:619.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Cbz-Phe-(Alloc)Lys-PAB-PNP | Cbz-Phe-(Alloc)Lys-PAB-PNP, MF:C41H43N5O11, MW:781.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

These research tools exemplify how rational design leverages both computational and experimental resources to achieve predictable outcomes. The integration of these components enables researchers to navigate complex design spaces efficiently, focusing experimental efforts on the most promising candidates identified through computational guidance.

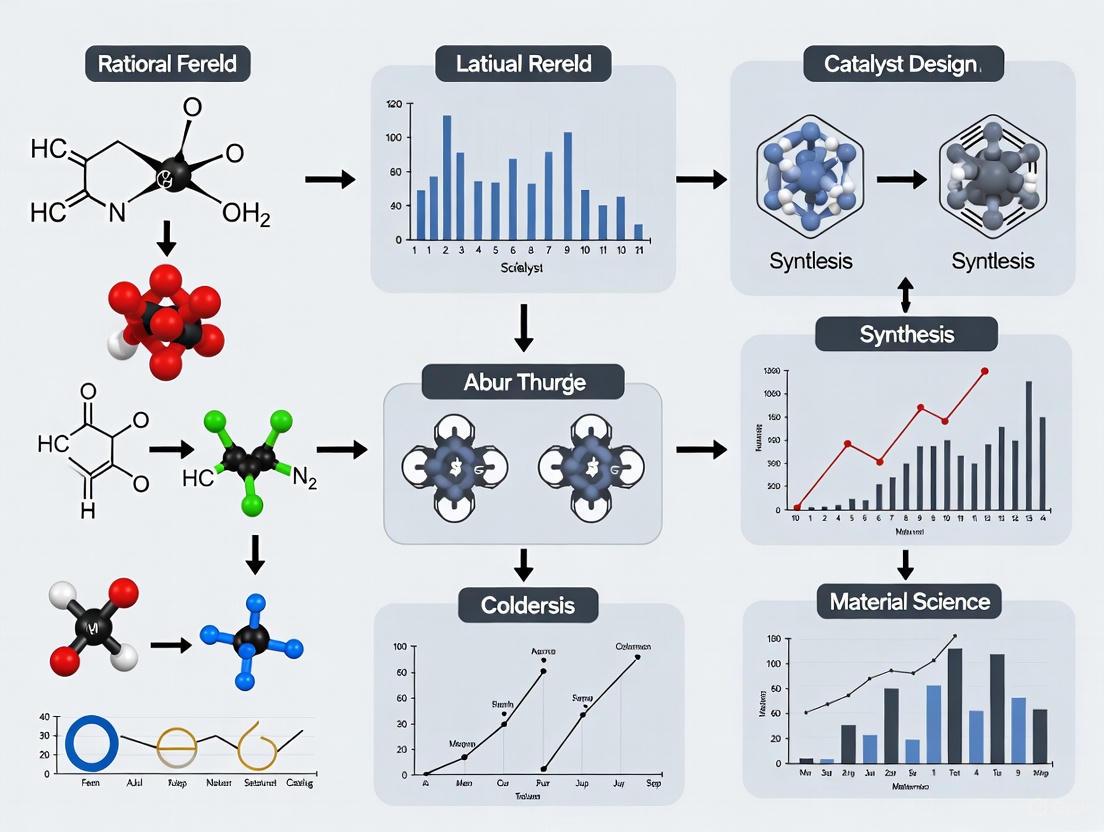

Visualization of Rational Design Framework

The rational design process follows an iterative cycle that integrates computational prediction with experimental validation, continuously refining models based on empirical data. This framework applies across diverse fields, from catalyst development to pharmaceutical design:

Diagram 2: Rational Design Cycle

This framework highlights the iterative nature of rational design, where each cycle enhances understanding of the system and improves predictive models. The feedback loop ensures continuous refinement of design principles, gradually reducing reliance on empirical optimization in favor of mechanism-driven predictions.

Future Perspectives and Challenges

Despite significant advances, rational design faces several challenges that must be addressed to fully realize its potential. In catalyst development, scalable synthesis of predicted materials remains a hurdle, as computational models often identify structures that are difficult to reproduce experimentally [1]. Similarly, predicting long-term catalyst stability and deactivation pathways requires more sophisticated models that account for dynamic surface reconstruction and leaching under operational conditions.

For pharmaceutical applications, the rational design of molecular glues must overcome selectivity challenges, as unintended protein degradation can lead to toxicity [3]. Advances in predictive modeling of protein-protein interactions and ligand-induced proximity will be crucial for designing more specific degraders. The integration of artificial intelligence with physics-based models promises to enhance prediction accuracy while reducing computational costs.

In genome engineering, further expansion of editing scope and enhancement of editing fidelity represent key objectives [4]. The development of PAM-free systems and more efficient reverse transcriptases will broaden therapeutic applications. Additionally, addressing delivery challenges remains critical for clinical translation of advanced editing technologies.

The convergence of rational design with automated experimentation and high-throughput characterization will likely accelerate the design-build-test-learn cycle across multiple domains. As computational power increases and algorithms become more sophisticated, rational approaches will continue to displace traditional trial-and-error methods, enabling more efficient and predictable development of advanced materials, therapeutics, and technologies.

Active site engineering represents the cornerstone of rational catalyst design, aiming to precisely control the atomic-scale environment where catalytic reactions occur. This paradigm shifts catalyst development from traditional trial-and-error approaches toward a principled methodology where structure-property relationships guide the creation of materials with tailored functionality. By manipulating the geometric arrangement and electronic properties of catalytic active sites, researchers can significantly enhance activity, selectivity, and stability across diverse chemical transformations. The emergence of sophisticated synthetic techniques coupled with advanced characterization methods has enabled unprecedented control at the atomic level, giving rise to distinct classes of engineered catalysts including single-atom catalysts (SACs), nanoclusters, and single-atom alloys (SAAs). These materials often exhibit dramatically different properties compared to their bulk or nanoparticle counterparts due to quantum confinement effects, optimized atom utilization, and synergistic interactions between multiple metal components. Framed within the broader context of rational catalyst design, active site engineering provides a systematic framework for bridging theoretical predictions with experimental realization, ultimately accelerating the development of next-generation catalytic materials for energy conversion, environmental remediation, and chemical production.

Fundamental Principles of Active Site Engineering

Coordination and Ligand Effects

The catalytic performance of an active site is predominantly governed by two fundamental phenomena: coordination effects and ligand effects. Coordination effects refer to the spatial arrangement of atoms within the active site, encompassing structural features such as crystal facets, defects, and corner sites that determine the number and geometry of adjacent atoms surrounding the catalytic center. These structural characteristics directly influence substrate adsorption strength and orientation. Ligand effects, conversely, describe the electronic interactions between the active metal center and its surrounding chemical environment, including support materials and neighboring heteroatoms, which modify electronic structure through charge transfer phenomena [5].

The intricate interplay between these effects creates the complex and diverse distribution of catalytic active sites found in real-world catalysts. In high-entropy alloy systems, for instance, the random spatial distribution of different elements combines with variations in local coordination environments to generate a vast spectrum of possible active site configurations, each with distinct catalytic properties [5]. Advanced topological analysis tools like persistent GLMY homology (PGH) have emerged as powerful mathematical frameworks for quantifying these three-dimensional structural sensitivities and establishing correlations with adsorption properties, enabling more precise manipulation of active site characteristics [5].

Synergistic Interactions in Multi-Component Systems

The strategic combination of multiple metal species at the atomic level can create synergistic effects that substantially enhance catalytic performance beyond what any single component could achieve. In dual-active site systems, such as Co/Cu single atoms and nanoclusters supported on nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes, the proximity between different metal centers enables cooperative reaction mechanisms where each site performs distinct functions within the catalytic cycle [6]. Experimental and theoretical studies have confirmed that the electronic structure modification caused by charge transfer between host and guest metals, combined with the unique geometric arrangement of the guest metal, is responsible for the high selectivity and catalytic activity observed in these systems [7].

These synergistic interactions often manifest as optimized adsorption energies for key reaction intermediates, which directly influence overall catalytic activity through linear scaling relationships and volcano-type correlations. In bimetallic CoCu catalysts, for example, the neighboring CoCu dual single-atom pairs in an anchored space create a unique electronic environment that significantly lowers the activation energy for ammonia borane hydrolysis (22.0 kJ·molâ»Â¹) while achieving exceptional hydrogen generation rates (41,974 mL·gâ»Â¹Â·minâ»Â¹) [6]. Similar principles apply to carbon-based heteronuclear metal atom catalysts, where the intricate interactions between different metal atom sites create multifunctional active centers capable of driving complex reaction networks with improved efficiency [8].

Categories of Engineered Active Sites

Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs)

Single-atom catalysts represent the ultimate limit of atom utilization, featuring isolated metal atoms stabilized on supporting substrates through covalent or ionic interactions with neighboring surface atoms (e.g., nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus) [6]. These materials exhibit superior reactivity and selectivity compared to nanoparticle-based catalysts in various reactions due to their unsaturated coordination environments and unique electronic structures. For instance, single platinum atoms supported on graphene nanosheets demonstrated 10 times higher activity than commercial Pt/C catalysts in methanol oxidation, attributed to the partially unoccupied 5d orbital of Pt [6]. Similarly, Pt single atoms on nitrogen-doped graphene showed 37 times higher activity for hydrogen evolution reactions [6].

The well-defined, uniform active sites in SACs make them ideal model systems for establishing precise structure-property relationships and mechanistic studies. Their maximized atom efficiency is particularly valuable for reactions involving expensive noble metals, significantly reducing catalyst costs while maintaining high performance. In hydrogen production and hydrogenation reactions, SACs have shown exceptional promise due to their high atomic utilization and uniform active sites, which can be systematically engineered to strengthen specific reaction steps [9]. The stability of SACs against agglomeration remains a key challenge, often addressed through strong metal-support interactions and appropriate coordination environments using nitrogen-doped carbon substrates [6].

Nanoclusters and Dual-Active Site Systems

Nanoclusters (NCs), typically consisting of a few to dozens of atoms, occupy an intermediate size regime between single atoms and nanoparticles, exhibiting distinct geometric and electronic structures that differ from both extremes. When strategically combined with single atoms in hybrid configurations, nanoclusters can create powerful dual-active site systems that leverage synergistic interactions between different types of active sites. In a notable example, a catalyst composed of CoCu nanoclusters and single-atom-doped carbon nanotubes demonstrated exceptional reactivity and stability for ammonia borane hydrolysis, achieving a remarkably high hydrogen generation rate of 41,974 mL·gâ»Â¹Â·minâ»Â¹ and maintaining performance over multiple cycles [6].

The enhanced performance in these systems arises from the complementary functions of different active sites: while single atoms often provide highly selective binding sites for specific reactants, neighboring nanoclusters can facilitate different steps in the reaction mechanism or stabilize key intermediates. Advanced characterization techniques including X-ray absorption near-edge spectroscopy (XANES) and high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) have been instrumental in identifying and analyzing the active sites within these complex architectures [6]. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations further elucidate the mechanisms underlying the enhanced activity, often revealing charge transfer phenomena and optimized adsorption energies at the interface between different catalytic components [6].

Single-Atom Alloys (SAAs)

Single-atom alloys represent a specialized class of bimetallic materials where guest metal atoms (typically noble metals) are atomically dispersed across the surface of a more abundant host metal (e.g., Ag, Cu) [7]. This configuration creates unique catalytic environments where the isolated guest atoms provide highly active sites for specific reaction steps, while the host matrix modulates selectivity and provides stability against poisoning. SAAs typically exhibit mean-field behavior with minimal energetic and spatial overlap between host and guest atoms, resulting in free-atom-like electronic structures on the guest elements that differ significantly from traditional nanoparticles [7].

The well-defined nature of SAA active sites, which lack the heterogeneity of vertices, steps, and interfaces found in conventional nanoparticles, contributes to exceptional selectivity in numerous catalytic transformations including selective hydrogenation, dehydrogenation, oxidation, and hydrogenolysis reactions [7]. The high dispersion of active sites also endows SAAs with superior intrinsic activity compared to monometallic catalysts, while the maximized utilization of precious metal atoms significantly reduces catalyst costs—particularly important for noble metal-based systems [7]. The thermal stability of SAAs, ensured by the formation of strong metal-metal bonds between guest and host atoms, addresses a key limitation of many single-atom systems prone to agglomeration under reaction conditions [7].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Engineered Active Site Architectures

| Active Site Type | Key Structural Features | Advantages | Common Synthesis Methods | Characterization Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs) | Isolated metal atoms on support; coordination with heteroatoms (N, O, P) | Maximum atom utilization; uniform active sites; high selectivity | One-pot pyrolysis; wet impregnation; atomic layer deposition | HAADF-STEM; XANES; in situ DRIFTS |

| Nanoclusters (NCs) | Few to dozens of atoms; sub-nanometer dimensions | Distinct electronic structure; synergy with SACs; multifunctionality | Co-reduction; sequential deposition; laser ablation | HAADF-STEM; XAFS; FT-EXAFS |

| Single-Atom Alloys (SAAs) | Guest metal atoms isolated on host metal surface | Poisoning resistance; high selectivity; tunable electronic structure | Initial wet impregnation; physical vapor deposition; galvanic replacement | AC-HAADF-STEM; CO-DRIFTS; XPS |

Synthesis Methodologies

Preparation of Single-Atom Alloys

The synthesis of single-atom alloys requires precise control to ensure atomic dispersion of guest metals while preventing their agglomeration into clusters or nanoparticles. Several sophisticated methodologies have been developed for this purpose:

Initial Wet Co-Impregnation: This widely employed method involves impregnating a support material with a precursor solution containing both host and guest metals, followed by adsorption, drying, and activation steps [7]. For example, Gong and colleagues successfully synthesized PtCu SAAs by dispersing γ-Al₂O₃ in a mixed H₂PtCl₆·6H₂O and Cu(NO₃)₂·3H₂O precursor solution, followed by static aging, drying in flowing air, and calcination at 600°C for 2 hours [7]. Characterization of the resulting material by AC-HAADF-STEM confirmed the presence of isolated Pt atoms continuously diluted within the Cu(111) surface, while in situ DRIFTS showed CO molecules linearly adsorbed on individually dispersed Pt atoms, confirming the SAA structure [7].

Step-wise Reduction Methods: These approaches involve initial synthesis of host metal nanoparticles followed by controlled deposition of guest metal atoms through various reduction techniques. The galvanic replacement (GR) method leverages differences in reduction potentials between guest and host metal precursors to drive spontaneous replacement reactions [7]. When the host metal possesses a lower reduction potential than the guest metal, the replacement occurs spontaneously, with high-intensity ultrasound often employed to facilitate the reaction rate and improve metal dispersion [7]. Other step-wise methods include successive reduction and electrochemical deposition, which provide additional control over the deposition process and final architecture [7].

Physical Vapor Deposition and Laser Ablation: Physical vapor deposition under ultra-high vacuum conditions allows for precise control over metal deposition at the atomic level, making it particularly suitable for model catalyst systems and fundamental studies [7]. Similarly, laser ablation in liquid techniques offers a versatile approach for generating SAA nanoparticles with controlled composition and size distribution [7].

Engineering Dual-Active Site Catalysts

The creation of catalysts with complementary active sites requires sophisticated synthesis strategies that precisely control the spatial distribution of different metal species:

One-Pot Pyrolysis Methods: These approaches involve the thermal decomposition of precursor mixtures containing metal salts and supporting materials to simultaneously generate both single-atom and nanocluster sites. In a representative synthesis for CoCu/Co-Cu-Nx-CNT catalysts, researchers first prepared melem-C₃N₄ (DCD-350) by heating dicyandiamide to 350°C for 2 hours [6]. This material was then mixed with Co(acac)₂ and Cu(acac)₂, ground thoroughly, and subjected to pyrolysis at 800°C under nitrogen atmosphere to form the final catalyst structure featuring both CoCu nanoclusters and atomically dispersed Co/Cu sites [6].

Sequential Impregnation Strategies: This methodology provides enhanced control over the distribution of different metal components by introducing them in a specific sequence. Studies on Fe-Mo-W/TiO₂ catalysts demonstrated that the impregnation order significantly influences active site formation and catalytic performance [10]. For instance, Mo-prioritized impregnation (Mo1st) followed by Fe+W co-impregnation generated catalysts with superior performance for multi-pollutant removal, achieving 93.86% NOx conversion between 260 and 420°C with over 94% removal efficiency for both benzene and toluene [10]. The sequence affects the interaction between metals and the support material, ultimately determining the nature and distribution of active sites.

Advanced Laser-Assisted Synthesis: Techniques such as pulsed laser liquid phase ablation enable the preparation of well-defined bimetallic systems with controlled atomic architecture. These methods offer unique advantages for creating metastable structures that might be inaccessible through conventional thermal synthesis routes [7].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Their Functions in Active Site Engineering

| Research Reagent | Function in Catalyst Synthesis | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Metal acetylacetonates (M(acac)â‚“) | Metal precursors providing controlled release during thermal treatments | Co(acac)â‚‚, Cu(acac)â‚‚ in CoCu/Co-Cu-Nx-CNT synthesis [6] |

| Dicyandiamide (C₂H₄N₄) | Nitrogen-rich precursor for carbon nitride supports and N-doped carbon materials | Preparation of melem-C₃N₄ intermediate [6] |

| Ammonia borane (H₃NBH₃) | Hydrogen storage material and reducing agent; substrate for hydrolysis reactions | Hydrogen production evaluation [6] |

| Metal chlorides (H₂PtCl₆, PdCl₂) | Precursors for noble metal incorporation | SAA synthesis via wet impregnation [7] |

| Metal nitrates (Cu(NO₃)₂, Fe(NO₃)₃) | Readily decomposable precursors for transition metal oxides | Preparation of host metal nanoparticles in SAA synthesis [7] |

Characterization and Analytical Techniques

Advanced In-Situ and Operando Methods

Understanding active site behavior under realistic reaction conditions requires characterization techniques that can probe catalysts during operation. Several advanced methods have proven particularly valuable:

Scanning Electrochemical Microscopy (SECM): This technique enables direct mapping of electrochemical activity with nanoscale resolution by scanning a miniaturized electrode tip close to the catalyst surface [11]. Richards and colleagues employed operando SECM with sub-20 nm spatial resolution to map oxygen evolution reaction (OER) activity on a semi-two-dimensional NiO catalyst, revealing that catalytic activity at the edge of NiO was significantly higher than at fully coordinated surfaces [11]. SECM has also been used to examine atom-utilization efficiency in single-atom catalysts, with studies on copper phthalocyanine-based SACs demonstrating Cu site utilization up to 95.6%, substantially higher than commercial Pt/C catalysts (34.6%) [11].

Scanning Electrochemical Cell Microscopy (SECCM): Developed to address limitations of SECM, this technique uses a nanopipette probe to confine the electrolyte, forming a highly localized electrochemical cell that enables higher spatial resolution (down to ~20 nm), higher temporal resolution (down to ~3 milliseconds), and greater flexibility in studying surfaces with higher roughness [11].

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS): Including both XANES and EXAFS, these methods provide element-specific information about oxidation states and local coordination environments, making them ideal for characterizing atomic dispersion in SACs and SAAs [6] [7]. For instance, Zhang et al. used Pd K-edge XANES to demonstrate charge transfer from Ag to Pd in Ag-alloyed Pd SAA samples, evidenced by lower white line intensity and shifts to lower energy compared to Pd foil [7].

High-Angle Annular Dark-Field Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (HAADF-STEM): This imaging technique provides direct visualization of atomic arrangements, allowing researchers to confirm the presence and distribution of isolated metal atoms in both SACs and SAAs [6] [7]. The technique was instrumental in characterizing 0.1Pt10Cu/Al₂O₃ SAA catalysts, where isolated Pt atoms were clearly observed diluted within the Cu(111) surface without evidence of Pt nanoparticle formation [7].

Computational Modeling and Machine Learning

The integration of computational approaches with experimental studies has dramatically accelerated active site engineering:

Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations: These quantum mechanical methods enable prediction of adsorption energies, reaction pathways, and activation barriers for specific active site configurations [6] [5]. DFT studies have been crucial for elucidating the mechanisms behind enhanced activity in bimetallic systems, such as the role of neighboring CoCu dual single-atom pairs in ammonia borane hydrolysis [6]. In high-entropy alloy systems, DFT calculations help navigate the vast compositional and structural space to identify promising active site configurations [5].

Topology-Based Variational Autoencoders (PGH-VAEs): This emerging machine learning framework combines persistent GLMY homology with deep generative models to enable interpretable inverse design of catalytic active sites [5]. The approach quantifies three-dimensional structural features of active sites and establishes correlations with adsorption properties, allowing researchers to understand how coordination and ligand effects shape the latent design space and influence adsorption energies [5]. This methodology has demonstrated remarkable predictive accuracy, achieving a mean absolute error of 0.045 eV in *OH adsorption energy predictions using only around 1100 DFT data points [5].

Microkinetic Modeling and Descriptor Analysis: These approaches bridge the gap between atomic-scale properties and macroscopic catalytic performance by establishing relationships between descriptor variables (e.g., adsorption energies, electronic structure parameters) and catalytic activity/selectivity [1]. Machine learning-guided descriptor analysis has been particularly valuable for predicting reaction pathways, overpotentials, and selectivity in complex reaction networks [12].

Diagram 1: Integrated Workflow for Rational Catalyst Design showing the cyclical process of synthesis, evaluation, computational analysis, and optimization that enables continuous improvement in active site engineering.

Applications in Catalytic Reactions

Hydrogen Production and Storage

Active site engineering has led to remarkable advances in hydrogen production technologies, particularly through the development of high-performance catalysts for hydrogen release from chemical storage materials:

Ammonia Borane Hydrolysis: The hydrolysis of ammonia borane (AB) represents a promising approach for hydrogen storage and release, with catalysts playing a crucial role in determining reaction efficiency. Engineered catalysts featuring dual-active sites have demonstrated exceptional performance for this reaction. Specifically, CoCu nanoclusters with atomically dispersed Co and Cu sites on nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes achieved an extraordinary hydrogen generation rate of 41,974 mL·gâ»Â¹Â·minâ»Â¹ with a low activation energy of 22.0 kJ·molâ»Â¹ [6]. The synergistic interaction between CoCu single atoms and nanoclusters in this system was identified as the key factor enabling ultrafast hydrogen release, with density functional theory calculations revealing that neighboring CoCu dual single-atom pairs in anchored spaces create unique electronic environments that facilitate the reaction [6].

Water Electrolysis: The hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) represents another critical pathway for hydrogen production where active site engineering has made significant contributions. Single-atom catalysts have demonstrated exceptional performance for HER, with Pt single atoms on nitrogen-doped graphene showing 37 times higher activity than conventional catalysts [6]. Similarly, transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) like WSâ‚‚, WTeâ‚‚, and MoTeâ‚‚ have emerged as promising HER catalysts due to their tunable electronic structures and surface properties, with defect engineering and heterostructure formation enabling further optimization of their active sites [12].

Environmental Catalysis

The removal of pollutants through catalytic processes has benefited substantially from engineered active sites with enhanced selectivity and stability:

Multi-Pollutant Removal (MPR): The simultaneous removal of NOx and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from industrial flue gases represents a challenging catalytic application where traditional catalysts often suffer from competitive adsorption and poisoning. Sequential impregnation synthesis of Fe-Mo-W/TiO₂ catalysts has enabled the creation of optimized active site distributions that achieve remarkable MPR performance, with Mo-prioritized impregnation followed by Fe+W co-impregnation yielding catalysts that maintain over 94% removal efficiency for both benzene and toluene while achieving 93.86% NOx conversion between 260-420°C [10]. The impregnation sequence was found to critically influence active site formation, with Mo-prioritized impregnation reducing the TiO₂ support's band gap and enhancing electron transfer capabilities, thereby improving O₂ activation and oxidation efficiency [10].

NOx Electroreduction: The electrocatalytic reduction of nitrogen oxides (NOx) to ammonia represents a sustainable strategy for both pollution mitigation and valuable chemical production. Optimizing the efficiency and selectivity of NOx electroreduction remains challenging due to competing side reactions and complex reaction networks [1]. Rational catalyst design guided by computational modeling has identified promising active site configurations for these processes, with density functional theory studies and microkinetic simulations providing mechanistic insights into reaction pathways, key intermediates, and activity-determining descriptors [1].

Energy Conversion Systems

Advanced catalytic materials with engineered active sites play crucial roles in various energy conversion technologies:

Oxygen Evolution/Reduction Reactions (OER/ORR): These coupled processes are fundamental to fuel cells and metal-air batteries, with transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) emerging as promising non-precious metal catalysts [12]. The synergistic interplay between experimental validation and computational modeling has been particularly fruitful in unraveling the electrocatalytic potential of TMD materials like WSâ‚‚, WTeâ‚‚, and MoTeâ‚‚ [12]. Defect engineering, heterostructure formation, and phase transitions in these materials have enabled precise control over active site properties, leading to significant improvements in OER/ORR activity [12].

Photo-Reforming of Biomass: The conversion of biomass-derived compounds like glucose into biofuels and chemicals through photo-reforming represents a promising renewable energy pathway. The rational design of advanced functional catalysts for this application requires careful optimization of material structure and active site properties to enhance selectivity and efficiency in complex cascade catalytic processes [13]. Key considerations include reaction mechanism elucidation, product selectivity control, and reaction condition optimization, all of which benefit from fundamental understanding of structure-activity relationships at active sites [13].

Diagram 2: Active Site Engineering Architecture illustrating how support materials, dopant elements, and controlled synthesis create synergistic interfaces between atomic sites and nanoclusters that enhance catalytic performance.

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The field of active site engineering continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends and persistent challenges shaping its trajectory. The integration of machine learning and artificial intelligence with traditional computational and experimental approaches represents a particularly promising direction. Inverse design methodologies, such as the topology-based variational autoencoder framework (PGH-VAEs), enable the generation of catalytic active sites tailored to specific performance criteria rather than relying solely on empirical optimization [5]. This paradigm shift from trial-and-error to predictive design could dramatically accelerate catalyst development cycles.

The growing complexity of catalytic systems, exemplified by high-entropy alloys and multi-atom catalysts, presents both opportunities and challenges. While these materials offer unprecedented tunability through vast compositional and structural diversity, their rational design requires advanced characterization techniques capable of probing active sites under operational conditions [11] [5]. The development of more sophisticated in-situ and operando methods with higher spatial, temporal, and energy resolution will be crucial for elucidating the dynamic evolution of active sites during catalytic reactions.

Scalable synthesis methodologies represent another critical frontier, as many advanced active site engineering strategies currently demonstrate proof-of-concept at laboratory scale but face significant barriers to industrial implementation. Techniques that enable precise control over atomic arrangement while remaining compatible with large-scale production processes will be essential for translating fundamental advances into practical technologies [7] [10]. Additionally, the stability of engineered active sites under harsh reaction conditions remains a persistent challenge, particularly for single-atom systems prone to agglomeration and leaching [6] [7].

As active site engineering continues to mature, its integration with broader catalyst design principles will enable increasingly sophisticated approaches to controlling catalytic performance across multiple length scales—from atomic coordination environments to reactor-level integration. This holistic perspective, combining fundamental understanding with practical implementation, will ultimately drive the development of next-generation catalytic materials for sustainable energy and chemical production.

Active site engineering has emerged as a powerful paradigm within the broader framework of rational catalyst design, enabling unprecedented control over catalytic performance through atomic-scale manipulation of active site structures. The strategic development of single-atom catalysts, nanoclusters, and single-atom alloys has demonstrated how precise control of coordination environments and electronic properties can lead to dramatic enhancements in activity, selectivity, and stability across diverse catalytic transformations. The continued advancement of this field relies on the tight integration of sophisticated synthesis methodologies, advanced characterization techniques, and computational modeling approaches that together provide fundamental insights into structure-property relationships. As characterization methods with higher spatial and temporal resolution become more widely available, and as computational approaches including machine learning continue to mature, the rational design of catalytic active sites will increasingly shift from empirical optimization to predictive engineering. This evolution promises to accelerate the development of advanced catalytic materials addressing critical challenges in energy conversion, environmental protection, and sustainable chemical production.

Tailoring the Interfacial Microenvironment for Enhanced Reactivity

The interfacial microenvironment—the local chemical and physical environment at the catalyst-electrolyte interface—is paramount in determining catalytic activity, selectivity, and stability. Within the broader thesis of rational catalyst design, moving beyond sole consideration of the catalyst's intrinsic structure to actively engineer its immediate surroundings represents a paradigm shift. This approach tackles the challenge of inefficient catalytic systems by optimizing the local reaction conditions at the active site, thereby breaking traditional scaling relationships and kinetic limitations. This guide details the principles and methodologies for tailoring these microenvironments, a strategy crucial for advancing sustainable energy technologies such as electrocatalytic CO₂ reduction (eCO₂RR) and hydrogen energy conversion [14] [15].

Theoretical Foundations

The efficacy of a catalyst is not solely governed by the atomic structure of its active sites but is profoundly influenced by the local microenvironment. This encompasses the local pH, electrolyte composition, water structure, and the presence of COâ‚‚-philic functional groups or promoters at the catalyst-electrolyte interface.

In eCOâ‚‚RR, the poor solubility of COâ‚‚ in aqueous electrolytes often limits mass transport to active sites, constraining overall reaction rates [16]. Furthermore, competing side reactions, most notably the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), can dominate without precise control over the local conditions. Engineering the interface to preferentially adsorb and concentrate COâ‚‚ molecules is a key strategy to overcome these hurdles [14].

Similarly, for hydrogen electrocatalysis (HER/HOR), the kinetics in alkaline media are often sluggish. Creating a local acidic microenvironment around the active site within a bulk alkaline electrolyte can significantly accelerate the reaction by facilitating optimal adsorption and dissociation of reaction intermediates [15].

The underlying principle across these applications is the strategic design of the interface to control the binding energy of intermediates, enhance mass transport, and suppress undesired parallel reactions, thereby achieving global optimization of the catalytic process [15] [16].

Key Tuning Strategies and Experimental Data

Catalyst Morphology and Surface Engineering

Precise control over the catalyst's physical architecture and surface chemistry directly shapes the interfacial microenvironment.

- Introduction of CO₂-philic Functional Groups: The introduction of surficial hydroxyl groups (-OH) on ZnO catalysts (ZnO–OH) via a MOF-assisted synthesis creates a CO₂-philic interface. Density functional theory calculations confirm a significantly more negative adsorption Gibbs free energy for CO₂ on ZnO–OH (-0.1466 eV) compared to pristine ZnO (-0.0028 eV), demonstrating enhanced CO₂ affinity. This leads to a high Faradaic efficiency for CO of 85% at -0.95 V vs. RHE, while simultaneously suppressing the HER [16].

- Constructing Triple Heterostructures: The design of a

Rusp/TiO₂–x-CeO₂–xelectrocatalyst creates a complex interface where Ru species are anchored on supports of TiO₂–x and CeO₂–x. This architecture serves a dual purpose: it generates electron-rich Ru sites that weaken the binding of intermediates (Had, OHad, CO*ad), and the CeO₂–x component, with its strong affinity for oxygen-containing species, adsorbs OH– ions to create a local acidic environment. This synergy results in exceptional HOR mass activity (4978 A/gRu) and high HER mass activity (3600 A/gRu at 50 mV overpotential) [15].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Catalysts with Engineered Microenvironments

| Catalyst | Reaction | Key Microenvironment Feature | Performance Metric | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO–OH [16] | eCO₂RR to CO | CO₂-philic -OH groups | Faradaic Efficiency (CO) | 85% @ -0.95 V vs. RHE |

| Rusp/TiO₂–x-CeO₂–x [15] | Alkaline HOR | Local acidic microenvironment & electron-rich Ru | Mass Activity | 4978 A/gRu |

| Rusp/TiO₂–x-CeO₂–x [15] | Alkaline HER | Local acidic microenvironment & electron-rich Ru | Overpotential @ 10 mA/cm² | 21 mV |

Electrolyte and Electrode Structure Engineering

The composition of the electrolyte and the macroscopic structure of the electrode are critical levers for defining the interfacial milieu.

- Electrolyte Engineering: Adjusting the buffer capacity, cation size (e.g., K⺠vs. Csâº), and ionic strength of the electrolyte can influence the local pH and the electric field at the electrode surface, thereby affecting product selectivity in eCOâ‚‚RR [14].

- Electrode Structure Design: The use of gas diffusion electrodes and three-dimensional porous frameworks can enhance COâ‚‚ mass transport to the active sites, addressing the critical limitation of COâ‚‚ solubility and increasing the overall conversion efficiency [14].

Table 2: Summary of Interfacial Microenvironment Tuning Strategies

| Tuning Strategy | Method | Primary Effect on Microenvironment | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Functionalization [16] | Grafting -OH groups | Increases local COâ‚‚ concentration & modulates intermediate binding | Enhanced COâ‚‚ adsorption; suppressed HER |

| Heterostructure Construction [15] | Coupling metals with metal oxide supports | Creates local acid-like regions & tailors electronic structure | Breaks pH-dependent kinetics; boosts HOR/HER |

| Defect Engineering [15] | Introducing oxygen vacancies | Alters local charge distribution and water network | Optimizes intermediate adsorption energy |

| Morphology Control [14] | Fabricating nanoporous, 3D structures | Improves reactant mass transport to the interface | Higher current densities and conversion rates |

Experimental Protocols

Synthesis of ZnO–OH with Surficial Hydroxyl Groups

This protocol details the creation of a COâ‚‚-philic catalyst surface [16].

- Synthesis of ZIF-8 Precursor: Dissolve 2-methylimidazole (1.230 g) in 50 mL of methanol. Separately, dissolve Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O (1.115 g) in 50 mL of methanol. Combine the two solutions with magnetic stirring and let react for 24 hours at room temperature without stirring. Recover the white precipitate by centrifugation, wash with methanol, and dry under vacuum.

- Transformation to Zn₅(OH)₈(NO₃)₂(H₂O)₂ Intermediate: Immerse 100 mg of as-synthesized ZIF-8 in 100 mL of an ethanol solution containing 0.5 g of Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O. Stir for 30 minutes. Recover the resulting sheet-shaped nanostructures, wash with ethanol, and dry under vacuum.

- Pyrolysis to ZnO–OH: Place the Zn₅(OH)₈(NO₃)₂(H₂O)₂ powder in a tube furnace. Pyrolyze at 400 °C for 90 minutes in air with a heating rate of 10 °C/min to yield the final ZnO–OH material.

Synthesis of Rusp/TiO₂–x-CeO₂–x Triple Heterostructure

This protocol creates a catalyst with a tailored electronic structure and local acidic microenvironment [15].

- Synthesis of Support and Incorporation of Ru: The

Rusp/TiO₂–x-CeO₂–xcatalyst is synthesized through a sequence involving hydrothermal treatment, ion exchange, and final high-temperature H₂/Ar annealing. This process anchors Ru species onto a composite TiO₂–x-CeO₂–x support. - Structural Characterization: The successful formation of the triple heterostructure with a cube-like morphology (average diameter ~80 nm) and the presence of electron-rich Ru sites should be confirmed using:

- Scanning Electron Microscopy

- Transmission Electron Microscopy

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy

Electrochemical Characterization for eCOâ‚‚RR

A standard setup for evaluating catalyst performance in COâ‚‚ reduction [16].

- Electrode Preparation (Ink-based): Create a homogeneous ink by dispersing 5 mg of catalyst powder and 100 μL of Nafion solution (5 wt.%) in 1 mL of ethanol via ultrasonication. Drop-cast 500 μL of the ink onto a 1 cm² carbon paper substrate (catalyst loading ~3 mg/cm²).

- H-cell Testing: Use a two-compartment H-cell separated by a Nafion N-117 membrane. Employ the prepared electrode as the working electrode, a Pt plate as the counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl electrode as the reference.

- Product Analysis: Purity COâ‚‚ gas into the cathode compartment at a constant flow rate (e.g., 20 mL/min). Analyze the gas-phase composition periodically using gas chromatography to determine Faradaic efficiency.

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Rational Catalyst Design Workflow

This diagram illustrates the integrated approach of rational catalyst design, where tailoring the microenvironment is a core component.

Local Acidic Microenvironment Creation

This diagram shows how a heterostructure catalyst can create a local acidic microenvironment to enhance reaction kinetics in a bulk alkaline electrolyte.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Microenvironment-Tailored Catalyst Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks | Sacrificial template and precursor for creating porous metal oxides with tailored surfaces. | Synthesis of ZnO–OH with surficial -OH groups [16]. |

| Ruthenium(III) Chloride Hydrate | Metal precursor for incorporating Ru active sites into heterostructure catalysts. | Preparation of Rusp/TiO₂–x-CeO₂–x electrocatalyst [15]. |

| Rare Earth Salts | Used to generate oxygen vacancies and modify the electronic structure of supports. | Ce(NO₃)₃·6Hâ‚‚O to create CeOâ‚‚â»Ë£ for enhanced OH– adsorption [15]. |

| Nafion Membrane & Solution | Serves as both an ion-exchange membrane in electrolysis cells and a binder in catalyst inks. | Standard component in H-cell setups and electrode preparation [16]. |

| Carbon Paper | Porous, conductive substrate for loading catalyst powders as a working electrode. | Used as the electrode support in both eCOâ‚‚RR and HOR/HER testing [16] [15]. |

| Boc-Phe-(Alloc)Lys-PAB-PNP | Boc-Phe-(Alloc)Lys-PAB-PNP, MF:C38H45N5O11, MW:747.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pholedrine hydrochloride | Pholedrine hydrochloride, CAS:877-86-1, MF:C10H16ClNO, MW:201.69 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Tailoring the interfacial microenvironment is a powerful and indispensable principle within rational catalyst design. Strategies such as implanting COâ‚‚-philic groups, constructing multi-component heterostructures, and engineering defect-rich supports have proven highly effective in enhancing reactivity and selectivity for critical energy conversion reactions. Moving forward, the field must focus on employing advanced in situ spectroscopic techniques to precisely elucidate the dynamic structural changes and intermediate interactions at the interface. Coupling these experimental insights with more sophisticated multi-scale modeling will enable the predictive design of next-generation catalytic systems, ultimately pushing the boundaries of conversion efficiency and selectivity for a sustainable energy future.

Support Interactions and Confinement Effects in Porous Materials

The rational design of catalysts represents a cornerstone in the advancement of sustainable energy and chemical processes. Within this framework, the interplay between support interactions and confinement effects in porous materials has emerged as a critical area of investigation. These phenomena collectively govern catalyst performance by influencing mass transport, transition states, and reaction kinetics within nanoscale environments. The strategic manipulation of these effects enables precise control over catalytic processes, bridging the gap between molecular-level understanding and macroscopic performance.

This technical guide examines the fundamental principles and experimental methodologies characterizing support interactions and confinement effects, with emphasis on their implications for rational catalyst design. We explore how nanoscale confinement alters thermodynamic properties and reaction pathways, how support materials dictate active site efficacy, and how advanced characterization and computational techniques provide unprecedented insights into these complex interactions. The integration of these concepts provides a robust foundation for designing next-generation catalytic systems with enhanced efficiency and selectivity.

Fundamental Principles of Confinement Effects

Thermodynamic Alterations under Confinement

Nanoscale confinement induces significant deviations from bulk phase behavior, profoundly impacting catalytic processes. Experimental investigations with ethane in MCM-41 nanoporous materials demonstrate that capillary condensation occurs at lower pressures than bulk saturation pressure, with the magnitude of this shift being pore-size dependent [17]. The following table summarizes key thermodynamic perturbations observed under confinement:

| Thermodynamic Property | Confinement-Induced Alteration | Experimental System | Impact on Catalysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capillary Condensation Pressure | Isothermally occurs at lower pressure than bulk saturation pressure [17] | Ethane in MCM-41 (6-12 nm pores) [17] | Alters reaction equilibrium, enables condensation at milder conditions |

| Critical Temperature | Reduction in pore critical temperature (TCp) compared to bulk fluid [17] | Ethane in controlled pore silica [17] | Modifies phase behavior, shifts supercritical boundaries |

| Hysteresis Behavior | Different capillary condensation and evaporation pressures under specific conditions [17] | Mesoporous materials with varying wettability [17] | Impacts reactant/product transport, catalyst regeneration |

| Molecular Mobility | Restricted diffusion affecting T1/T2 NMR relaxation ratio [18] | Water in MCM-41, SBA-3, KIT-6 silica [18] | Influences reaction rates, intermediate stability, product selectivity |

These thermodynamic alterations stem from the amplified influence of surface forces within nanoscale volumes. The pore critical temperature (TCp) delineates the boundary beyond which discrete capillary condensation and evaporation processes vanish, replaced by continuous pore-filling mechanisms [17]. This transition has profound implications for catalytic reactions occurring within porous architectures.

Classification of Porous Materials and Confinement Regimes

The evolution of porous materials classification provides critical insights into confinement effects. Porous Materials 1.0 encompass traditional frameworks with uniform pore size distribution at a single length scale, including zeolites, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and activated carbons [19]. While offering well-defined confinement environments, these materials often suffer from diffusion limitations that restrict catalytic efficiency [19].

The development of Porous Materials 2.0 introduced hierarchical architectures with multi-level pore structures, enhancing mass transport while maintaining confinement benefits [19]. This evolution necessitates advanced design principles, quantitatively described by Su's Law (the generalized Murray's Law), which establishes relationships between pore sizes across different hierarchy levels and their corresponding mass transport efficiencies [19].

The confinement regime experienced by molecules depends critically on the relationship between pore diameter and molecular dimensions, as illustrated below:

Figure 1: Classification of confinement regimes in porous materials based on pore size and dominant effects.

Support Interactions in Porous Materials

Mechanisms of Support-Active Site Interactions

Support interactions encompass the complex physicochemical relationships between catalytic active sites and their porous hosts. These interactions extend beyond mere physical anchoring to include electronic modulation, spatial organization, and stabilization of transition states. The interfacial microenvironment can be strategically engineered through several mechanisms:

Electronic Structure Modulation: Support materials directly influence the electronic properties of catalytic active sites through charge transfer phenomena. This modification alters the binding energy of reaction intermediates, potentially optimizing the energy landscape for specific catalytic pathways [20]. For instance, cationic and anionic doping in support structures creates electron-rich or electron-deficient environments that modulate intermediate adsorption/desorption kinetics [20].

Confinement-Induced Transition State Stabilization: The nanoscale architecture of porous supports can stabilize specific transition state geometries through spatial constraints, effectively lowering activation barriers for desired pathways while suppressing competing reactions [21]. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in microporous systems where pore dimensions approach molecular scales.

Interfacial Microenvironment Engineering: Functionalization with organic molecules creates tailored microenvironments around active sites that influence local pH, polarity, and substrate concentration [20]. These engineered environments can dramatically enhance catalytic efficiency by optimizing the immediate surroundings where reactions occur.

Wettability and Surface Chemistry Effects

The wettability of porous supports profoundly influences fluid distribution, molecular accessibility, and ultimately catalytic performance. Systematic investigations using MCM-41 materials with controlled surface chemistry reveal that hydrophilic nanoporous materials adsorb greater quantities of alkanes than their hydrophobic counterparts, with concomitant increases in capillary condensation pressures [17]. This wettability-dependent behavior directly impacts catalytic reactions where reactant concentration at active sites determines overall rates.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) relaxometry provides powerful insights into molecular mobility and interactions within confined spaces. The ratio of spin-lattice (T1) to spin-spin (T2) relaxation times serves as a sensitive probe of surface affinity and molecular mobility at solid-liquid interfaces [18]. Functionalized mesoporous silica materials exhibit distinct T1/T2 ratios that correlate with surface chemistry, enabling quantitative assessment of wettability effects on confined molecules [18].

Experimental Characterization Methodologies

Adsorption-Desorption Isotherm Analysis

The measurement of adsorption and desorption isotherms provides fundamental insights into confinement effects and support interactions. The following protocol details the experimental methodology for characterizing porous materials:

Protocol: Adsorption-Desorption Isotherm Measurement Using Nano-Condensation Apparatus

Objective: To determine capillary condensation pressures, hysteresis behavior, and confined phase properties of fluids in nanoporous materials.

Materials and Equipment:

- Nano-condensation apparatus with sensitive microbalance [17]

- Nanoporous materials with controlled pore geometry (e.g., MCM-41, SBA-15) [17]

- High-purity adsorbate (e.g., ethane, 99% purity) [17]

- Temperature-controlled chamber (±0.1°C stability)

- Vacuum system for degassing

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Pre-treat nanoporous materials under vacuum at elevated temperatures to remove contaminants and adsorbed species [17].

- System Calibration: Calibrate microbalance accounting for buoyancy effects using reference materials [17].

- Isotherm Measurement:

- Maintain constant temperature (±0.1°C) throughout experiment

- Incrementally increase pressure while measuring adsorbed mass

- Continue until saturation conditions are reached

- Reverse process with incremental pressure decreases for desorption branch

- Data Analysis:

- Identify capillary condensation pressure from adsorption branch inflection

- Determine capillary evaporation pressure from desorption branch

- Calculate hysteresis loop area between adsorption and desorption branches

- Compute pore critical temperature from series of isotherms at different temperatures

Key Parameters:

- Temperature range: -20°C to 20°C for ethane studies [17]

- Pressure resolution: ≤0.1 Pa

- Mass measurement accuracy: ±1 μg [17]

Data Interpretation:

- Capillary condensation pressure shifts relative to bulk saturation pressure indicate confinement strength [17]

- Hysteresis behavior reveals information about pore geometry and connectivity [17]

- Disappearance of hysteresis at elevated temperatures identifies hysteresis critical temperature (Th) [17]

NMR Relaxometry for Textural Characterization

NMR relaxometry enables characterization of porous materials in liquid-saturated states, providing complementary information to gas adsorption techniques:

Protocol: Surface Area and Pore Size Analysis via NMR Relaxometry

Objective: To determine specific surface area and pore size distribution of solvated porous materials using spin-spin relaxation measurements.

Materials and Equipment:

- NMR spectrometer with relaxometry capabilities

- Ordered mesoporous silica model materials (MCM-41, SBA-3, KIT-6) with well-defined pore sizes [18]

- Deuterated solvent for locking signal

- Fully wetting fluid (e.g., water for hydrophilic surfaces)

Procedure:

- Sample Saturation: Immerse porous material in excess wetting fluid ensuring complete pore filling [18].

- Relaxation Measurement:

- Employ Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) pulse sequence for T2 measurements

- Acquire decay curves with sufficient signal-to-noise ratio

- Repeat measurements for statistical reliability

- Data Processing:

- Invert relaxation data to obtain T2 distribution

- Apply two-fraction-fast-exchange model adapted for cylindrical pore geometry [18]

- Calculate surface-to-volume ratio from surface relaxivity

Key Parameters:

- Echo time: Optimized for pore size range

- Number of echoes: Sufficient for complete decay characterization

- Temperature control: ±1°C during measurement

Data Interpretation:

- Surface relaxivity correlates with pore size and surface chemistry [18]

- T2 distribution directly relates to pore size distribution [18]

- T1/T2 ratios provide information on molecular mobility and surface affinity [18]

Limitations and Considerations:

- Model requires adaptation for pores <10 nm due to confinement effects on fluid properties [18]

- Surface relaxivity depends on material composition and fluid-surface interactions [18]

Advanced Characterization Techniques

The comprehensive understanding of support interactions and confinement effects requires multi-technique approaches:

| Characterization Technique | Information Obtained | Applications in Support/Confinement Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Argon 87 K Adsorption | Surface area, pore size distribution, pore volume [18] | Benchmark characterization for nanoporous materials [18] |

| Water Vapor Adsorption | Hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity, interaction strength [18] | Wettability assessment under realistic conditions [18] |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations | Adsorption energies, phase behavior prediction [17] | Modeling confined fluid behavior, validating experimental data [17] |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulations | Molecular-level transport phenomena, configuration analysis [17] | Studying capillary condensation mechanisms [17] |

| High-Throughput Electrochemical Testing | Catalyst activity, stability, selectivity [22] | Automated performance screening under varying conditions [22] |

Quantitative Framework for Confinement Effects

Critical Temperatures and Pore Size Thresholds

Experimental investigations with ethane in MCM-41 nanoporous materials reveal distinct critical pore sizes governing confinement effects. The lower critical pore diameter (dc) and upper critical pore diameter (DC) define the size range within which discrete vapor-liquid phase transitions occur [17]. Outside this range, fluids either exist in a supercritical state (D < dc) following continuous pore-filling processes, or exhibit bulk-like behavior (D > DC) [17].

The following table summarizes quantitative data on critical temperatures and pore size thresholds for ethane in controlled pore materials:

| Pore Size (nm) | Hysteresis Critical Temperature, Th (°C) | Pore Critical Temperature, TCp (°C) | Capillary Condensation Pressure Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 7.3 ± 0.5 | 18.2 ± 0.7 | 32.5 ± 1.2 |

| 8 | 4.1 ± 0.4 | 15.8 ± 0.6 | 28.7 ± 1.1 |

| 10 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 12.5 ± 0.5 | 22.4 ± 0.9 |

| 12 | -2.5 ± 0.4 | 9.3 ± 0.6 | 17.8 ± 0.8 |

Table 1: Experimentally determined critical temperatures and capillary condensation pressure reductions for ethane in MCM-41 with varying pore sizes [17].

Temperature exerts profound influence on confined phase behavior, with systems progressing from hysteresis to reversible transition and ultimately to supercritical states as temperature increases [17]. The hysteresis critical temperature (Th) marks the boundary between hysteretic and reversible capillary condensation, while the pore critical temperature (TCp) indicates the transition to supercritical behavior where discrete condensation processes vanish [17].

AI-Enhanced Prediction of Porous Material Properties

Recent advances in artificial intelligence provide powerful tools for predicting structure-property relationships in porous materials. Machine learning approaches have demonstrated that just four key microstructural features can accurately predict the mechanical behavior of porous materials: porosity, internal surface area, mean grain size, and connectivity [23]. This finding dramatically streamlines the design process for catalytic supports optimized for specific applications.

The integration of AI extends to inverse design problems, where models predict optimal microstructural features for desired strength characteristics [23]. These AI-generated designs have been validated through 3D-printing and mechanical testing, confirming the predictive capabilities of these approaches [23]. The workflow for AI-enhanced porous material design is illustrated below:

Figure 2: Workflow for AI-enhanced design of porous materials, integrating forward prediction and inverse design with experimental validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental investigation of support interactions and confinement effects requires specialized materials and methodologies. The following table details essential research reagents and their applications:

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MCM-41 Mesoporous Silica | Model nanoporous material with tunable pore size (2-10 nm) [17] | Hexagonal pore arrangement, high surface area, uniform pore size distribution [17] | Surface modification possible via silylation; pore size controlled by template selection [17] |

| SBA-15 Mesoporous Silica | Model material for larger mesopores (5-30 nm) [18] | Larger pores than MCM-41, thicker walls, higher hydrothermal stability [18] | Suitable for studying confinement in larger mesopore range [18] |

| KIT-6 Silica | 3D porous network for diffusion studies [18] | Cubic Ia3d structure, interpenetrating cylindrical pores, 3D connectivity [18] | Enables investigation of connectivity effects on confinement [18] |

| High-Purity Ethane (99%) | Model hydrocarbon for confinement studies [17] | Simple molecular structure, relevant to energy applications [17] | Enables precise measurement of capillary condensation pressures [17] |

| Surface Modification Agents | Wettability control (e.g., organosilanes) [17] | Convert hydrophilic surfaces to hydrophobic variants [17] | Allows systematic study of wettability effects on confinement [17] |

| Deuterated Solvents | NMR studies of confined fluids [18] | Enable lock signal stabilization while studying H-containing fluids [18] | Essential for high-resolution NMR relaxometry measurements [18] |

| Methyl 27-hydroxyheptacosanoate | Methyl 27-hydroxyheptacosanoate, CAS:369635-50-7, MF:C28H56O3, MW:440.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Kadsuric acid 3-Me ester | Kadsuric acid 3-Me ester, MF:C31H48O4, MW:484.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Implications for Rational Catalyst Design

Design Principles for Confinement-Optimized Catalysts

The integration of support interactions and confinement effects into catalyst design strategies enables unprecedented control over catalytic performance. Several foundational principles emerge:

Hierarchical Pore Architecture Optimization: The design of catalysts with multi-level pore structures (Porous Materials 2.0) balances the benefits of strong confinement in smaller pores with enhanced mass transport through larger interconnected channels [19]. This approach addresses the diffusion limitations inherent in single-scale porous materials [19].

Synchronized Diffusion-Reaction Kinetics: Optimal catalytic efficiency requires precise matching of diffusion behaviors with reaction rates across multiple steps in complex reaction networks [19]. Rapid diffusion over short distances may cause undesirable interactions between different active sites, while extended diffusion paths can promote side reactions [19].

Wettability-Engineered Reaction Environments: Strategic control over support surface chemistry enables creation of optimized microenvironments that enhance reactant concentration at active sites while facilitating product desorption [17] [18]. Hydrophilic surfaces preferentially adsorb polar species, while hydrophobic environments concentrate non-polar reactants.

Emerging Frontiers and Future Directions

The field of support interactions and confinement effects continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising research directions:

AI-Driven Porous Material Discovery: The integration of large-language models with machine learning approaches enables automated extraction of structure-property relationships from literature and high-throughput prediction of optimal material configurations [24] [23]. These approaches dramatically accelerate the discovery cycle for tailored catalytic supports.

Reaction-Conditioned Generative Models: Advanced AI frameworks such as CatDRX employ reaction-conditioned variational autoencoders to generate catalyst structures optimized for specific reaction environments [25]. These models learn the complex relationships between reaction components, catalyst structures, and performance outcomes.

Operando Characterization Techniques: The development of advanced characterization methods that probe support interactions and confinement effects under actual reaction conditions provides unprecedented insights into working catalysts, bridging the gap between idealized models and practical performance [18].

Murray Material Design: The application of Su's Law (generalized Murray's Law) enables quantitative design of hierarchical pore structures with optimized mass transport properties for specific reactant and product molecules [19]. This approach represents a shift from trial-and-error optimization to mathematically-precise pore engineering.