Reviving Catalytic Power: Advanced Regeneration Strategies for Deactivated Catalysts

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of catalyst deactivation and regeneration, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Reviving Catalytic Power: Advanced Regeneration Strategies for Deactivated Catalysts

Abstract

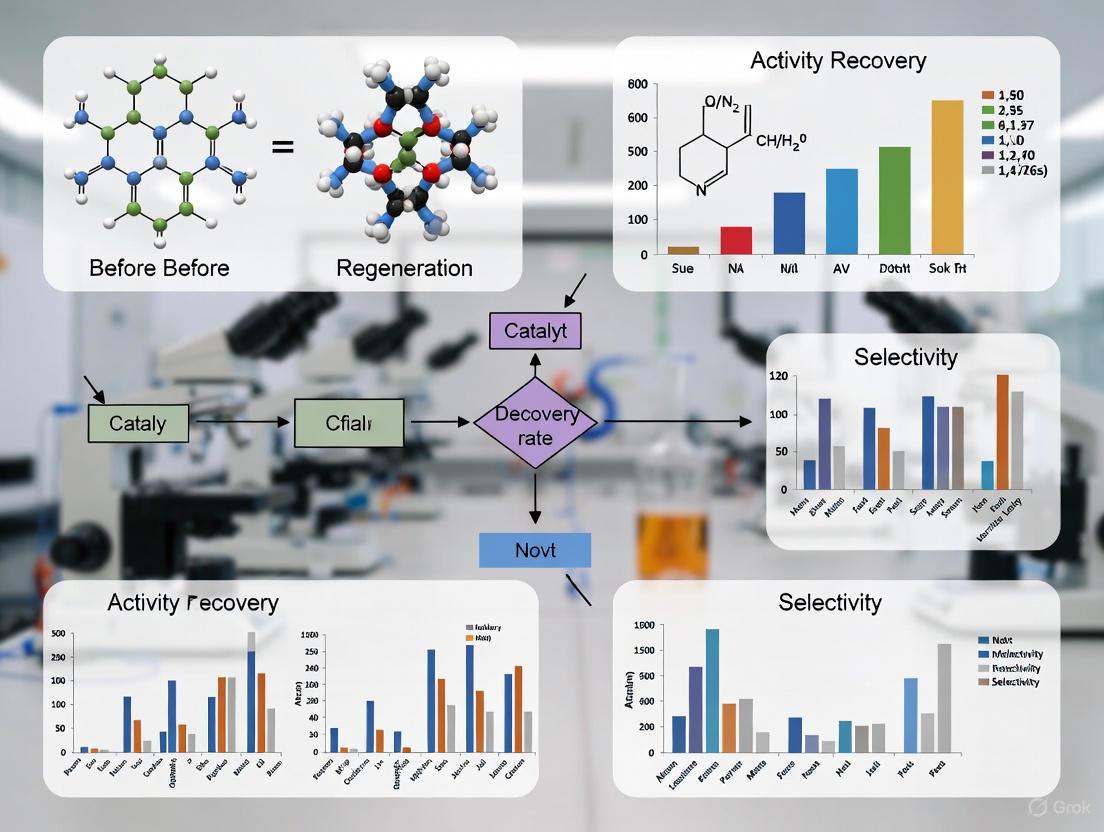

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of catalyst deactivation and regeneration, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental mechanisms of catalyst deactivation, including coking, poisoning, and thermal degradation. The scope covers both established and emerging regeneration methodologies, discusses common operational challenges and optimization strategies, and evaluates the techno-economic and environmental aspects of different approaches. By integrating foundational science with applied troubleshooting, this review serves as a strategic guide for selecting and implementing regeneration protocols to enhance catalyst longevity and support sustainable process development in biomedical and industrial applications.

Understanding Catalyst Deactivation: Mechanisms and Fundamental Pathways

The Inevitability of Catalyst Deactivation in Industrial Processes

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Common Catalyst Deactivation Mechanisms

Problem: A gradual but steady decline in catalyst activity is observed over time.

Diagnosis: This pattern often points to chemical poisoning or fouling [1] [2].

- Action: Analyze the feedstock for impurities. Common poisons include sulfur (e.g., H₂S), lead, mercury, phosphorus, and arsenic [1]. Elemental analysis techniques like XRF can identify these contaminants on the spent catalyst surface [2].

- Mitigation: Implement pre-treatment of reactant streams using guard beds (e.g., ZnO for sulfur removal) or catalytic hydrodesulfurization [1] [3].

Problem: A sudden, rapid drop in catalytic activity and/or a rise in pressure drop across the reactor.

Diagnosis: This is characteristic of coking or masking, where carbonaceous deposits or other substances physically block pores and active sites [1] [4].

- Action: Perform surface area analysis (BET). A significant reduction in surface area and pore volume confirms this mechanism [2]. Temperature-programmed oxidation (TPO) can characterize the type of coke.

- Mitigation: Optimize reaction conditions, such as increasing the steam-to-hydrocarbon ratio in reforming processes or adjusting temperature to minimize coking [1]. Consider catalysts designed with higher coke resistance [5].

Problem: Loss of activity following exposure to high temperatures, often accompanied by a permanent loss of surface area.

Diagnosis: This indicates thermal degradation (sintering), where catalyst particles agglomerate [1] [3].

- Action: Use chemisorption and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to measure the increased particle size of the active metal or support [6] [3].

- Mitigation: Operate at lower temperatures if possible. Use catalyst formulations with thermal stabilizers or supports that resist sintering [2].

Problem: Catalyst activity is inhibited in the presence of water vapor, but may be recovered under dry conditions.

Diagnosis: This is a reversible water inhibition effect. For example, Pd-based catalysts for hydrocarbon oxidation can be deactivated by hydroxyl groups that accumulate on the active PdO phase and at the metal-support interface [6].

- Action: In situ characterization like DRIFTS can identify the presence of surface hydroxyls [6].

- Mitigation: For some catalysts, periodic regeneration with hydrogen can remove the deactivating species [6].

Guide 2: Systematic Root Cause Analysis

When deactivation occurs, a systematic approach to identifying the root cause is essential. The following workflow outlines a logical diagnostic pathway, from initial observation to corrective actions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Is catalyst deactivation always unavoidable? Yes, deactivation is inevitable over time in industrial processes. All catalysts have a finite life, which can range from seconds (e.g., fluid catalytic cracking) to several years (e.g., ammonia synthesis) [7]. The high surface area of catalysts is thermodynamically unstable, driving processes like sintering. The key for industry is to slow the deactivation rate and develop effective regeneration protocols [1] [8].

Q2: What is the difference between a catalyst poison and coke? A poison is an impurity in the feed (e.g., H₂S, As, Hg) that chemically bonds strongly to the active sites, rendering them inactive [1] [2]. Coke is a carbonaceous material formed from the reaction feedstock or products that deposits on the surface, physically blocking active sites and pores (fouling) [1] [4]. Poisoning is a chemical effect, while coking is a physical blockage.

Q3: Can a sintered catalyst be regenerated? Sintering is often irreversible because it involves the agglomeration of small metal particles into larger, thermodynamically more stable ones, with a lower surface area [3]. While certain metal/support combinations (like Pt/CeO₂) can be redispersed with high-temperature oxidative treatment, this is not universally applicable [3]. For irreversibly sintered catalysts, the only options are replacement or recycling of precious metals [3].

Q4: How can I test for catalyst stability during early-stage research? It is critical to "deal with it early" [9]. Consider deactivation during R&D by:

- Using actual biomass-derived or industrial feedstocks that contain real-world impurities [9].

- Performing extended-duration experiments beyond the initial "break-in" period [9].

- Employing accelerated aging processes, which subject the catalyst to high-severity conditions or highly contaminated feeds to simulate long-term deactivation in a shorter time [4].

Q5: What are my options when a catalyst is deactivated? You have four main choices [10]:

- Regenerate: Restore activity through thermal, chemical, or reductive treatment (e.g., burning off coke with air, washing with water for soluble poisons like potassium [9], or using H₂ to remove surface hydroxyls [6]).

- Repurpose: Use the deactivated catalyst for a different application.

- Recycle: Recover valuable components, like precious metals, where refining recovery can approach 90% or higher [3].

- Dispose: The last resort, which should be done in an environmentally compliant manner.

Quantitative Data on Deactivation

Common Catalyst Poisons and Their Effects

| Poison Category | Specific Examples | Primary Effect on Catalyst | Common Industrial Processes Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfur Compounds [1] | H₂S, Thiophene | Strong chemisorption on metal sites (e.g., Ni), blocking active centers. | Steam reforming, Hydrotreating |

| Heavy Metals [1] | Pb, Hg, As | Forms alloys or strong complexes with active metal sites. | Reforming, Automotive exhaust |

| Group 15 Elements [1] | P, As, Sb, Bi | Electron lone pairs form dative bonds with transition metals. | Various hydrogenation reactions |

| Halogens [10] | Chlorine species | Can form volatile metal chlorides or stable surface compounds. | VOC Oxidation |

| Alkali & Alkaline Earth Metals [9] | Potassium (K) | Poisons Lewis acid sites on catalyst supports. | Biomass Fast Pyrolysis |

Comparison of Regeneration Methods

| Regeneration Method | Typical Application | Mechanism | Limitations / Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Oxidation | Coke removal [4] [10] | Burns off carbon deposits using air or oxygen at high temperature. | Risk of thermal damage and sintering if temperature is not controlled [3]. |

| Reductive Treatment | Water/OH group removal [6] | H₂ reduces surface species (e.g., hydroxyls on PdO) to restore active sites. | Requires a safe process for handling H₂; may need subsequent re-oxidation [6]. |

| Water Washing | Removal of soluble poisons [9] | Leaches out deposited poisons (e.g., potassium) from the catalyst surface. | Effective only for water-soluble deposits; may not restore all activity [9]. |

| Chemical Treatment | Specific poison removal | Uses a chemical agent to react with or compete with the poison for active sites. | Can be expensive and may introduce other impurities [1]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Accelerated Deactivation Testing for Hydrotreating Catalysts

This protocol is designed to simulate months of industrial catalyst deactivation in a laboratory setting, based on methodologies used for CoMo/γ-Al₂O₃ and NiMo/γ-Al₂O₃ hydrotreating catalysts [4].

Objective: To rapidly assess catalyst stability and susceptibility to coking. Materials:

- Reactor: Fixed-bed flow reactor capable of high-pressure operation.

- Feedstock: Industrial feed (e.g., gas oil) or a model compound spiked with known coke precursors (e.g., polyaromatics) or poisons.

- Conditions: Operate at higher-than-normal severity:

- Load the fresh catalyst into the reactor and activate under standard sulfiding conditions.

- Switch to the accelerated aging feed and conditions.

- Monitor catalyst performance over time (e.g., hydrodesulfurization conversion).

- Terminate the test once a target conversion loss (e.g., 20-50%) is reached.

- Characterize the spent catalyst using BET surface area, TPO for coke quantification, and elemental analysis for metal deposits [4].

Protocol 2: Regeneration of a Water-Deactivated Pd/θ-Al₂O₃ Catalyst

This protocol details the regeneration of a Pd-based catalyst deactivated by water during propane oxidation, as demonstrated in recent literature [6].

Objective: To restore the activity of a PdO catalyst poisoned by surface hydroxyl groups. Materials:

- Deactivated Catalyst: Pd/θ-Al₂O₃ catalyst after exposure to wet propane oxidation feed.

- Gases: 10% H₂/Ar (or N₂), pure O₂, inert gas (Ar or N₂).

- Reactor: Tubular reactor with temperature control. Procedure:

- Flush: After reaction, cool the reactor under inert gas flow.

- Reductive Regeneration: Heat the catalyst to 350-450°C under a flow of 10% H₂/Ar (e.g., 30 mL/min) and hold for 1-2 hours. This step removes the deactivating hydroxyl groups [6].

- Flush: Cool and flush the reactor with inert gas to remove residual H₂.

- Re-oxidation: Heat the catalyst to the standard reaction temperature (e.g., 250-350°C) under a flow of pure O₂ or air and hold for 1 hour to re-form the active PdO phase [6].

- Activity Test: Return to standard reaction conditions to evaluate the recovery of catalytic activity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Deactivation & Regeneration Studies | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Model Poison Compounds (e.g., H₂S, Thiophene, PH₃) [1] | To deliberately and controllably poison catalysts in laboratory studies to understand poisoning mechanisms and test resistance. | Doping a reactant stream with low ppm levels of H₂S to study sulfur tolerance of a reforming catalyst. |

| Guard Bed Adsorbents (e.g., ZnO) [1] | Used upstream of the main catalyst to remove specific poisons from the feed, extending catalyst life. | A ZnO guard bed protects a Ni-based steam reforming catalyst from sulfur poisoning. |

| Temperature-Programmed (TP) Gases | Gases like O₂ (TPO), H₂ (TPR), and NH₃ (TPD) are used to characterize deactivated catalysts. | TPO measures the temperature and amount of CO₂ released when burning coke off a catalyst, informing regeneration parameters [10]. |

| Characterization Standards | Certified reference materials for calibrating instruments like XPS, XRF, and BET analyzers. | Essential for ensuring quantitative and comparable data when analyzing fresh vs. deactivated catalysts [2]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is catalyst coking and how does it differ from general carbon deposition?

Coking is a specific type of catalyst deactivation characterized by the deposition of carbonaceous materials (coke) on the catalyst surface or within its pores. This is a subset of the broader phenomenon of carbon deposition. Coking specifically leads to deactivation by blocking active sites and pores, while carbon deposition can sometimes be benign or even beneficial in certain reactions. The carbonaceous species formed can range from amorphous carbon to highly structured graphitic carbon and carbon filaments (whiskers) [11].

Q2: What are the primary mechanisms by which coke deactivates a catalyst?

Coke deactivates catalysts through three principal mechanisms:

- Site Blocking (Encapsulation): Carbonaceous species adsorb strongly on the catalyst's active sites, rendering them unavailable for the intended reaction [11] [12].

- Pore Blocking: Coke deposits physically block the micro- and mesopores of the catalyst, preventing reactant molecules from accessing the internal active sites [11] [12].

- Mechanical Destruction: In severe cases, such as whisker carbon formation, the growth of carbon filaments can generate significant mechanical force, leading to the disintegration of the catalyst pellet itself [11] [13].

Q3: Are all forms of carbon deposition reversible?

No, the reversibility depends on the type of carbon and the regeneration method. Coking is often considered a reversible deactivation mechanism [12] [14]. Carbonaceous deposits can frequently be removed through processes like oxidation (burning with air/O2 or O3) or gasification (with H2O or H2) [12] [14]. However, the regeneration process must be carefully controlled, as the exothermic nature of coke combustion can cause localized hot spots and thermal damage (sintering) to the catalyst, which is an irreversible form of deactivation [12].

Q4: What are the main types of coke formed on catalysts?

The structure and formation temperature of coke vary significantly, impacting the deactivation phenomenon and regeneration strategy. The table below summarizes three common types.

Table 1: Common Types of Carbon Deposits on Catalysts

| Carbon Type | Formation Mechanism | Typical Formation Temperature | Impact on Catalyst |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whisker/Filamentous Carbon | Diffusion of carbon through metal crystals (e.g., Ni), leading to nucleation and filament growth with the metal crystal at the tip [11] [13]. | >300°C [11] | Causes gradual deactivation, can increase pressure drop, and may physically break down catalyst particles [11] [13]. |

| Encapsulating Carbon/Polymers | Slow polymerization of hydrocarbon radicals on the metal surface into an encapsulating film [11]. | <500°C [11] | Leads to gradual deactivation by coating (encapsulating) the active metal particles, blocking access to active sites [11]. |

| Pyrolytic Carbon | Thermal cracking of hydrocarbons in the gas phase, leading to the deposition of carbon precursors on the catalyst [11]. | >600°C [11] | Results in encapsulation of entire catalyst particles, causing rapid deactivation and increased pressure drop [11]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosis and Analysis

A systematic approach to diagnosing coking involves a combination of reaction monitoring and advanced characterization techniques.

Step 1: Monitor Reaction Performance

A decline in catalyst performance is the first indicator of deactivation. Track conversion, selectivity, and system pressure drop over time. A sudden increase in pressure drop often suggests massive pore blocking or whisker carbon growth [11].

Step 2: Select Appropriate Characterization Techniques

Post-mortem analysis of the deactivated catalyst is crucial to confirm coking as the root cause. The following table outlines key techniques and the specific information they provide.

Table 2: Key Characterization Techniques for Diagnosing Coking

| Technique | Function in Coking Diagnosis | Key Information Provided |

|---|---|---|

| BET Surface Area Analysis | Measures the reduction in specific surface area and pore volume [2]. | Quantifies the loss of accessible surface area and indicates pore blockage [2]. |

| Temperature-Programmed Methods (TPO/TPD) | Analyzes the oxidation (TPO) or desorption (TPD) behavior of carbon species as temperature increases [2]. | Identifies the type and reactivity of coke by its oxidation/desorption temperature; helps understand poisoning strength [2]. |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Probes the vibrational modes of carbon-carbon bonds [15]. | Distinguishes between different carbon structures (e.g., disordered "D band" vs. graphitic "G band") [15]. |

| Electron Microscopy (SEM/TEM) | Provides high-resolution imaging of the catalyst surface and structure [11]. | Directly visualizes carbon morphology (e.g., filaments, encapsulating layers) and their location [11]. |

| Hard X-ray Nanotomography (PXCT) | Generates quantitative 3D maps of electron density within entire catalyst particles [15]. | Visualizes and localizes coke deposition in 3D at the nanoscale, revealing severity and distribution within the particle [15]. |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Detects elemental composition and chemical states on the catalyst surface [2]. | Identifies the presence of surface contaminants and can characterize surface carbon species [2]. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical process for diagnosing and addressing catalyst coking:

Experimental Protocols for Studying Coking

Protocol 1: Accelerated Coking and Operando Raman Spectroscopy

This protocol is used to simulate coking and monitor carbon formation in real-time [15].

- Catalyst Activation: Place the catalyst (e.g., Ni/Al2O3) in a reactor and activate under a flow of 25% H2/He (20 mL/min) at the required temperature (e.g., 673 K).

- Apply Coking Conditions: Switch the gas feed to an artificial coking atmosphere, such as 4% CH4/He (20 mL/min), at the target temperature (e.g., 673 K) for a set duration (e.g., 30 minutes).

- Operando Raman Monitoring: During the coking step, use an operando Raman spectroscopy probe to collect spectra. The emergence of the D band (~1340 cm⁻¹) and G band (~1590 cm⁻¹) indicates the formation of disordered and graphitic carbonaceous species, respectively [15].

- Post-Analysis: Correlate the Raman data with online mass spectrometry of the effluent gas to quantify activity loss alongside coke formation.

Protocol 2: Post-Mortem Analysis via Ptychographic X-ray Computed Tomography (PXCT)

This advanced technique provides 3D nanoscale visualization of coke within a catalyst particle [15].

- Sample Preparation: Select a coked catalyst particle (diameter ~30-50 μm). Mount it on a tomography pin using a Focused Ion Beam-Scanning Electron Microscope (FIB-SEM) and deposit a protective Pt layer to minimize damage.

- Data Collection: Perform the PXCT experiment at a synchrotron beamline (e.g., I13-1, Diamond Light Source). Collect 2D ptychography projections from multiple angles by rotating the sample.

- Tomogram Reconstruction: Use iterative algorithms (e.g., ePIE) to reconstruct the 2D projections. Align and reconstruct them into a 3D tomogram, achieving a voxel size of ~37 nm and a resolution of ~80 nm.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the 3D quantitative map of local electron density (Nₑ). Segment the tomogram to distinguish pores, the catalyst body, and coke. Coke formation is identified by localized changes in electron density within the nanoporous solid, which is not detectable in the resolved macropores [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Coking Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Model Coke-Prone Catalysts (e.g., Ni/Al2O3) | A standard catalyst highly susceptible to coking; used to study mechanisms and test regeneration strategies in reactions like methane cracking or dry reforming [13] [15]. |

| Gas Mixtures (H₂/He, CH₄/He, Air/O₂) | H₂/He for catalyst activation (reduction); CH₄/He for simulating coking conditions; Air/O₂ for regeneration via controlled oxidation [15]. |

| Guard Beds (e.g., ZnO) | Used upstream of the main catalyst to remove potential catalyst poisons like H₂S from the feed, helping to isolate the coking deactivation mechanism [14]. |

| Reference Catalysts (e.g., Fe-based) | Used as comparative materials, as iron particles are known to form little to no carbon in certain conditions, helping to benchmark coking behavior [11]. |

| Hierarchical Meso-/Macroporous Supports | Catalyst supports engineered with interconnected pore networks to improve mass transport and mitigate pore blocking by coke, thereby enhancing catalyst stability [15]. |

Regeneration Strategies: From Principle to Practice

Regeneration aims to remove carbonaceous deposits while preserving the catalyst's intrinsic structure. The choice of method depends on the coke type and catalyst stability.

Table 4: Common Regeneration Methods for Coked Catalysts

| Regeneration Method | Principle | Experimental Considerations | Pros & Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidation with Air/O₂ | Coke is combusted to form CO/CO₂. C + O₂ → CO/CO₂ [12] [13] | Highly exothermic; requires precise temperature control to prevent sintering. Start with low O₂ concentrations [12]. | + Effective, widely used.- Risk of thermal damage, may not be selective. |

| Gasification with Steam (H₂O) | Coke reacts with steam to form CO/CO₂ and H₂. C + H₂O → CO + H₂ [14] [13] | Endothermic reaction, easier to control temperature than oxidation. Can be part of a chemical-looping process [13]. | + Milder, less risk of sintering.- Slower than oxidation. |

| Gasification with Hydrogen (H₂) | Coke is hydrogenated to methane. C + 2H₂ → CH₄ [12] [13] | Requires high H₂ pressure. Can be integrated into reaction cycles (e.g., in methane cracking) [13]. | + Produces valuable CH₄.- High cost of H₂, may not remove all coke types. |

| Advanced Oxidation (O₃, NOₓ) | Uses stronger oxidants to remove coke at lower temperatures [12]. | Ozone (O₃) can regenerate zeolites like ZSM-5 at low temperatures, minimizing thermal stress [12]. | + Low-temperature operation.- Higher cost of oxidants, complex handling. |

The diagram below illustrates the multi-step decision pathway for selecting and executing a catalyst regeneration strategy.

The information in this guide provides a foundation for troubleshooting coking issues. Successful long-term catalyst management requires integrating these diagnostic and regenerative practices into a holistic strategy that includes prudent catalyst selection, careful control of operating conditions, and continuous monitoring.

Catalyst Poisoning by Feedstock Impurities and Reaction By-products

Troubleshooting Guides

Why has my catalyst's activity dropped suddenly despite using the same feedstock source?

A sudden drop in catalytic activity is often a classic sign of catalyst poisoning due to impurities in the feedstock. This occurs when substances strongly adsorb to the catalyst's active sites, blocking reactants from accessing them [16].

Diagnosis Checklist:

- Step 1: Analyze Feedstock Composition. Check for recent changes or spikes in the concentration of common poisons in your feedstock. Use techniques like Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) or Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) to detect and quantify trace contaminants [16].

- Step 2: Characterize the Deactivated Catalyst. Perform surface analysis on a sample of the spent catalyst to identify adsorbed poisons.

- Step 3: Correlate Findings. Match the identified poisons on the catalyst with the impurities found in the feedstock to confirm the source.

Solution: If the poisoning is reversible, the activity can be recovered. For example, potassium poisoning on a Pt/TiO₂ catalyst was shown to be reversible via simple water washing [9]. If the poisoning is irreversible, such as strong sulfur chemisorption on nickel catalysts, the catalyst may need replacement [17] [18]. To prevent recurrence, implement a guard bed—a sacrificial bed of material placed upstream of the main reactor—to trap poisons before they reach your primary catalyst [19] [16].

How can I distinguish catalyst poisoning from other deactivation mechanisms like coking or sintering?

Correctly identifying the deactivation mechanism is crucial for selecting the right mitigation or regeneration strategy. The table below summarizes key diagnostic features.

Table 1: Differentiating Common Catalyst Deactivation Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Primary Cause | Effect on Catalyst | Common Diagnostic Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poisoning | Chemical binding of impurities (e.g., S, P, heavy metals) to active sites [18]. | Loss of active sites without necessarily changing the physical surface area; often selective [17]. | XPS, TPD, Elemental Analysis [2] [16]. |

| Coking | Deposition of carbonaceous materials [14]. | Pore blockage and physical masking of active sites; can be reversible [14] [20]. | BET (for surface area/pore volume loss), Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) [2]. |

| Sintering | Exposure to high temperatures, especially in steam [14] [2]. | Agglomeration of metal particles, leading to a permanent loss of active surface area [14]. | BET, Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) [2]. |

Experimental Workflow for Diagnosis: The following diagram outlines a systematic workflow to diagnose the root cause of catalyst deactivation.

My catalyst is in a continuous flow reactor and losing activity steadily. Is it poisoning and can it be recovered?

A steady decline in activity in a continuous system is highly indicative of progressive catalyst poisoning, often from trace impurities in the feed [17] [18].

Diagnosis Protocol: Switch to a purified feed (e.g., one that has passed through a guard bed or adsorbent) while monitoring the catalyst's activity. If the deactivation rate slows or the activity stabilizes, feedstock poisoning is confirmed [17].

Regeneration Strategies within the Context of a Broader Thesis: The regeneration strategy depends on whether the poisoning is reversible.

- Reversible Poisoning: For poisons that adsorb strongly but can be desorbed, Temperature-Programmed Desorption (TPD) can be used to determine the optimal regeneration temperature [18] [16]. The catalyst is heated in a stream of inert or reducing gas to desorb the poison without damaging the catalyst structure.

- Irreversible Poisoning: If the poison has formed a stable chemical compound with the active site (e.g., nickel sulfide), regeneration becomes challenging. High-temperature treatment with steam can remove sulfur but may cause sintering [17]. Oxidation in air can form sulfates, which are also undesirable [17]. Therefore, for irreversibly poisoned catalysts, prevention is more effective than regeneration. This underscores the thesis that while regeneration is a key research area, designing poison-tolerant catalysts and processes is paramount for long-term stability.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the most common catalyst poisons found in biomass-derived feedstocks?

Biomass feedstocks present a unique set of catalyst poisons, which are often biogenic in nature [17]. The table below lists the primary culprits.

Table 2: Common Poisons in Biomass Feedstocks and Their Effects

| Poison Category | Specific Examples | Mechanism of Poisoning | Affected Catalysts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkali Metals | Potassium (K), Sodium (Na) [17] [9] | Ion exchange with Brønsted acid sites; can also poison metal centers [17]. | Zeolites, ReOx-based catalysts, Ni catalysts [17] [9]. |

| Sulfur Compounds | Hydrogen Sulfide (H₂S), Sulfur-containing amino acids (e.g., cysteine) [17] | Strong, often irreversible chemisorption on metal sites [17] [18]. | Ni, Pt, Pd, other noble metals [17]. |

| Nitrogen Compounds | Amino acids (non-sulfur), Ammonia [17] | Reversible or weak adsorption on active sites [17]. | Metal catalysts (less severe than S) [17]. |

| Heavy Metals | Lead (Pb), Mercury (Hg), Arsenic (As) [19] [21] | Form stable complexes with active sites [19]. | Various metal catalysts. |

| Chlorine | HCl [21] | Can react with the catalyst surface, altering its properties [21]. | Various catalysts, can accelerate sintering [14]. |

How can I design an experiment to test the poisoning effect of a specific impurity?

To systematically assess the poisoning effect of a suspected impurity, you can design a controlled addition experiment.

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Baseline Activity Test: Conduct your target reaction (e.g., hydrogenation) using a pure feedstock under standard conditions (temperature, pressure, flow rate). Measure the key performance metrics, such as conversion and selectivity, to establish a baseline [17].

- Intentional Poisoning: Repeat the reaction under identical conditions, but deliberately add a known concentration of the suspected poison to the feed. It is insightful to conduct this in a continuous flow system to monitor the rate of deactivation over time [17].

- Post-Reaction Characterization: Analyze the spent catalyst from step 2 using techniques like XPS and TPD to confirm the adsorption and strength of binding of the poison [17] [2].

- Regeneration Test (Optional): Attempt to regenerate the poisoned catalyst using methods such as thermal treatment, oxidation, or chemical washing. Re-test the regenerated catalyst's activity to determine if the poisoning was reversible and to evaluate the effectiveness of the regeneration protocol [17] [22].

What are the advanced strategies for making catalysts more resistant to poisoning?

Beyond feedstock purification, advanced catalyst design is key to enhancing poison resistance.

- Poison-Tolerant Catalyst Formulations: This involves developing catalysts with active sites that are inherently less susceptible to poisoning. Strategies include:

- Alloying: Adding a second metal (e.g., Au, Cu, Bi to Ni) can shift the d-band center of the active metal, reducing its affinity for sulfur adsorption [17].

- Use of Mo-based Catalysts: Molybdenum-based catalysts are known for their high sulfur tolerance and can be used for direct methanation without the need for desulfurization [17].

- Promoter Addition: Additives like molybdenum oxide (MoO₃) can mitigate the poisoning effects of alkali metals on vanadium-based SCR catalysts [18].

- Core-Shell Structures: Designing catalysts with a protective shell can selectively filter out poison molecules before they reach the active sites in the core.

- Guard Beds and Poison Traps: As a process solution, integrating sacrificial materials like ZnO (for sulfur removal) upstream of the main catalyst can effectively protect it [14] [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Poisoning and Regeneration Studies

| Item | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Guard Bed Materials (e.g., ZnO) | Placed upstream of the main catalyst reactor to remove specific poisons like H₂S from the feedstream, protecting the valuable primary catalyst [14] [19]. |

| Poison Precursors (e.g., H₂S, (C₂H5)4Pb) | Used to deliberately introduce a known amount of poison in controlled laboratory experiments to study deactivation kinetics and mechanisms [17]. |

| Temperature Programmed Desorption (TPD) Setup | A key diagnostic tool that uses controlled heating under inert gas to study the strength and quantity of species adsorbed on a catalyst surface, helping to identify and quantify poisoning [18] [16]. |

| Regeneration Gases (e.g., O2, H2, Steam) | Used in catalyst regeneration protocols. O₂ can gasify carbon deposits (coking) or oxidize some poisons; H₂ can reduce oxidized metal sites; steam can remove sulfur (with caveats of potential sintering) [17] [14] [22]. |

| Supercritical Fluids (e.g., CO2) | An emerging regeneration technology (Supercritical Fluid Extraction) for removing coke and other deposits from catalyst pores with high efficiency and potentially less damage than thermal methods [18] [22]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary mechanisms of catalyst deactivation? Catalyst deactivation occurs through several primary mechanisms: poisoning, where strong chemical adsorption of impurities (e.g., H₂S, Hg) blocks active sites; coking or fouling, involving carbonaceous deposits that physically cover active sites and pores; and thermal degradation/sintering, where high temperatures cause irreversible loss of active surface area via crystallite growth and support collapse [12] [9] [1].

Q2: Is deactivation by sintering reversible? Typically, sintering is an irreversible process [1]. The loss of active surface area results from the thermodynamic driving force that reduces surface energy, causing crystallites to agglomerate and support structures to collapse [12] [1]. Recovery of the original, highly dispersed state is generally not feasible, though some activity may be recovered through re-dispersion techniques, which are often complex and only partially effective.

Q3: How can thermal degradation be experimentally detected? Key characterization techniques include:

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): To monitor increases in crystalline size and phase changes [23].

- Surface Area and Porosity Analysis (BET): To quantify the loss of specific surface area [23].

- Temperature-Programmed Reduction (TPR): To assess changes in metal-support interactions.

- Chemisorption: To directly measure the loss of active metal surface area [4].

Q4: What are the critical operational factors that accelerate thermal sintering? The primary factors are:

- High Temperature: Exceeding the Tammann temperature of the active phase or support.

- Oxidizing Atmosphere: Can enhance surface mobility of species.

- Presence of Steam: Often accelerates sintering and support degradation [9].

- Chemical Environment: Certain reactants or by-products can facilitate atom mobility.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing the Root Cause of Catalyst Deactivation

Follow this diagnostic workflow to identify the primary deactivation mechanism in your system.

Guide 2: Selecting a Regeneration Strategy for Thermally Degraded Catalysts

This guide helps select an appropriate regeneration pathway, though options for purely sintered catalysts are limited.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Accelerated Thermal Aging Study

This protocol simulates long-term thermal degradation in a condensed timeframe [4].

Objective: To rapidly assess the thermal stability of a catalyst formulation under controlled high-temperature conditions.

Materials:

- Fresh catalyst sample (accurately weighed)

- Tubular furnace or fixed-bed reactor system

- High-purity air or nitrogen gas stream

- Temperature controller and data logger

- Gas flow controllers

Procedure:

- Load a known mass of fresh catalyst into the reactor.

- Purge the system with an inert gas (N₂) at room temperature for 15 minutes.

- Ramp the temperature to the target aging temperature (e.g., 50-100°C above intended operating temperature) at a controlled rate (e.g., 5°C/min).

- Maintain the catalyst at the target temperature for a predetermined period (e.g., 24-120 hours) under a continuous gas flow.

- Cool the reactor to room temperature under the same gas atmosphere.

- Unload the thermally aged catalyst for characterization.

Characterization (Pre- and Post-Aging):

- BET Surface Area: To quantify surface area loss.

- XRD: To determine crystallite growth of the active phase.

- Pore Size Distribution: To assess changes in porosity.

- Chemisorption: To measure active metal surface area dispersion.

Protocol 2: Regeneration of a Coked and Sintered Catalyst

This protocol addresses a common scenario where coking and sintering occur simultaneously [23].

Objective: To remove carbonaceous deposits via controlled oxidation while minimizing further thermal damage.

Materials:

- Deactivated catalyst sample

- Muffle furnace or controlled reactor

- Diluted air or oxygen stream (1-5% O₂ in N₂)

- Temperature controller

Procedure:

- Load the spent catalyst into the furnace.

- Introduce a dilute oxygen stream (e.g., 2% O₂ in N₂) at a low flow rate.

- Slowly heat the sample to a moderate temperature (e.g., 400-500°C) to combust coke. A slow ramp (1-3°C/min) is critical to avoid hot spots.

- Hold at the target temperature for 2-6 hours, monitoring for completion (often indicated by a return to baseline CO₂ concentration).

- Cool the regenerated catalyst in an inert atmosphere.

- Characterize the regenerated catalyst (BET, XRD) to assess the success of coke removal and the extent of irreversible sintering.

Quantitative Data on Deactivation

Table 1: Characteristic Temperatures for Catalyst Thermal Degradation [4] [1]

| Material / Process | Critical Temperature | Observed Structural Change |

|---|---|---|

| Supported Metal Nanoparticles (e.g., Ni, Pt) | Tammann Temperature (~0.5 x Tmelt, K) | Onset of significant atomic mobility and sintering |

| γ-Al₂O₃ Support | >800°C | Phase transition to low-surface-area α-Al₂O₃ |

| Zeolites (e.g., HZSM-5) | >600°C | Dealumination, framework collapse, severe surface area loss |

| Coke Combustion (Regeneration) | 400-550°C | Exothermic oxidation risk; can cause local sintering |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Deactivation & Regeneration Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Diluted O₂ in N₂ (1-5%) | Controlled coke oxidation during regeneration | Prevents runaway exotherms and further sintering [23] |

| Acetic Acid Solution | Acid washing to remove inorganic deposits (e.g., CaCO₃) | Effective for regenerating catalysts deactivated in high-alkalinity wastewater [24] |

| Thermal Spray Coating Precursors | Application of protective coatings to enhance thermal stability | Can mitigate support degradation under cyclic operation |

| Chlorine-containing Compounds (e.g., CCl₄) | Re-dispersion agents for sintered metals | Used in high-temperature treatment to volatilize and re-spread metal phases |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Catalyst Deactivation and Regeneration Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Diluted O₂ in N₂ (1-5%) | Controlled coke oxidation during regeneration | Prevents runaway exotherms and further sintering [23] |

| Acetic Acid Solution | Acid washing to remove inorganic deposits (e.g., CaCO₃) | Effective for regenerating catalysts deactivated in high-alkalinity wastewater [24] |

| Chlorine-containing Compounds (e.g., CCl₄) | Re-dispersion agents for sintered metals | Used in high-temperature treatment to volatilize and re-spread metal phases |

| Steam Generator | Simulating hydrothermal aging conditions | Critical for testing catalyst stability in processes involving water vapor [9] |

| Nitric Oxide (NO) / Ozone (O₃) | Alternative oxidants for low-temperature coke removal | Can regenerate activity at lower temperatures than O₂, minimizing thermal damage [12] |

Mechanical Damage and Attrition in Catalyst Systems

Within catalyst regeneration research, mechanical damage and attrition present significant challenges to sustainable catalytic system design. Attrition, the gradual wear and tear of catalyst particles, leads to activity loss, pressure drop issues, and catalyst fines that can elude reactor containment [25]. This technical support center provides a foundational guide for diagnosing, quantifying, and mitigating these physical deactivation pathways, with content framed within the broader context of advancing regeneration strategies for deactivated catalysts.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between catalyst attrition and other common deactivation modes like coking or poisoning?

Catalyst attrition is a physical deactivation mechanism involving the mechanical wearing down of catalyst particles into fines, resulting in mass loss and reduced particle size. In contrast, coking (carbon deposition) and poisoning (chemical adsorption of impurities) are chemical deactivation mechanisms that block active sites without necessarily altering the physical integrity of the catalyst particle [12] [25]. While coking is often reversible through oxidation, attrition is an irreversible process that permanently removes catalyst material [12].

2. Why is understanding attrition crucial for the design of regeneration strategies?

Recognizing the dominant attrition mechanism is essential for developing targeted mitigation strategies. If abrasion is the primary mechanism, efforts should focus on hardening the particle surface and reducing abrasive interactions. If fracture dominates, improving the particle's bulk mechanical strength and minimizing high-impact events becomes the priority [26]. Furthermore, distinguishing between physical attrition and chemical deactivation prevents the misapplication of regeneration techniques; a chemically regenerated catalyst may still be prone to rapid re-deactivation if its mechanical strength has been compromised.

3. What are the standard laboratory methods for evaluating a catalyst's resistance to attrition?

The most common accelerated wear tests used in industry and research are the Air Jet Method (e.g., ASTM D5757) and the Jet Cup Method (e.g., the Davison Index) [26]. These tests subject catalyst samples to high-velocity air streams, generating fines through particle-to-particle and particle-to-wall collisions. The amount of fines generated is then measured and reported as an attrition index. While these methods provide valuable comparative data, they are accelerated proxies and do not perfectly mimic the exact conditions of a commercial reactor [26].

4. Can a catalyst that has undergone significant attrition be regenerated?

Attrition is generally considered an irreversible form of deactivation. Regeneration strategies like thermal treatment or chemical washing are designed to remove chemical poisons or deposits, but they cannot restore lost catalyst mass or the original particle size distribution [12] [27]. Therefore, the primary focus regarding attrition should be on prevention and management through robust catalyst design, appropriate reactor operation, and the use of filtration systems to recover and contain valuable catalyst fines [25].

Troubleshooting Guide

Symptom: High Catalyst Loss from Fluidized Bed Reactor

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Procedure | Recommended Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| High Fines in Fresh Catalyst | Perform particle size distribution (PSD) analysis on fresh catalyst feed. | Source fresh catalyst with a lower percentage of sub-20 micron fines [26]. |

| Poor Attrition Resistance | Conduct a standardized jet cup or air jet test (e.g., Davison Index); compare against known benchmarks [26]. | Select a catalyst formulation with higher mechanical strength and a better attrition index [26]. |

| Excessive Fluidization Velocity | Review and calibrate reactor flow rates and pressure drops. | Optimize fluidization gas velocity to maintain bed dynamics without causing excessive shear [25]. |

| Abrasion from Surface Contaminants | Perform elemental analysis (e.g., XRF) on collected fines; look for enrichment of surface contaminants like Ca, Fe, Ni [26]. | Improve feed pre-treatment to reduce contaminant ingress; use guard beds [26]. |

Symptom: Increased Pressure Drop Across Fixed-Bed Reactor

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Procedure | Recommended Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Bed Compaction from Fines | Measure PSD of catalyst sampled from the top of the bed. Shut down and inspect for plugged flow channels. | Ensure proper catalyst loading techniques; use graded beds with larger particles at the inlet. |

| Fines Migration | Install and monitor in-line particle filters or sample ports downstream of the reactor. | Install high-quality, high-temperature sintered metal filters to trap fines before they enter downstream sections [25]. |

| Mechanical Crushing | Inspect for damaged catalyst pellets or signs of excessive bed weight. | Ensure catalyst support structures are adequate; avoid over-tightening catalyst beds during loading. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Analysis

Protocol 1: Jet Cup Attrition Testing

This protocol outlines the method for determining the Davison Index (DI), a common measure of catalyst attrition resistance.

1. Objective: To quantify the propensity of a fresh catalyst to generate fines under accelerated, high-shear conditions.

2. Equipment and Reagents:

- Jet Cup apparatus (specific dimensions vary by standard)

- Drying oven

- Precision balance (0.1 mg accuracy)

- Sieve shaker and certified sieves (0-20 μm, 20-40 μm, etc.)

- Sample splitter

- Fresh catalyst sample (~50 cc)

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Dry the catalyst sample at 110°C for a minimum of 2 hours to remove moisture.

- Step 2: Weigh out a representative sample (e.g., 50.0 g) using a sample splitter.

- Step 3: Place the sample into the jet cup apparatus. Ensure the bottom gas distribution plate is clean and unobstructed.

- Step 4: Subject the catalyst to a high-velocity air jet for a specified duration (e.g., 1 hour at a controlled flow rate).

- Step 5: Carefully remove the catalyst from the cup. Gently separate the generated fines from the parent particles using a 20-micron sieve.

- Step 6: Weigh the mass of the fines collected on the sieve.

4. Data Analysis and Calculation:

Calculate the Davison Index (DI) using the formula:

DI = (Mass of Fines / Initial Catalyst Mass) × 100%

A lower DI value indicates a more attrition-resistant catalyst. For FCC catalysts, fresh catalyst DI values typically range from 3-10, while equilibrium catalyst (E-cat) values are below 2 [26].

Protocol 2: Fines Composition Analysis

This protocol helps diagnose the primary mechanism of attrition by analyzing the chemical composition of the generated fines.

1. Objective: To determine if attrition occurs primarily via abrasion (surface wear) or fracture (bulk breakage).

2. Procedure:

- Step 1: Collect attrited fines from a commercial unit or lab test, and obtain a representative sample of the bulk equilibrium catalyst (E-cat).

- Step 2: Perform elemental analysis on both the fines and the E-cat samples using techniques like X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) or Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP).

- Step 3: Calculate the concentration ratio for each element:

Ratio = [Element] in Fines / [Element] in E-cat.

3. Data Interpretation:

- Abrasion-Dominated Attrition: Fines will be enriched in elements concentrated on the particle surface (e.g., contaminants like Calcium, Iron, Nickel). Elements uniformly distributed in the particle (e.g., Aluminium, Silicon) will have a ratio close to 1 [26].

- Fracture-Dominated Attrition: The composition of the fines will be similar to the bulk E-cat for all elements, as the particle is breaking apart volumetrically.

Quantitative Data from Industry Analysis:

| Element | Distribution in Particle | Concentration Ratio (Fines/E-cat) Indicates Abrasion |

|---|---|---|

| Aluminium, Silicon | Uniform | ~1.0 |

| Calcium, Iron, Nickel | Surface Concentrated | >>1.0 (Significantly Enriched) |

Source: Analysis of 94 commercial FCC units, showing fines enrichment in surface contaminants [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Key Reagents and Materials for Attrition Testing and Mitigation

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Jet Cup Apparatus | Standardized laboratory equipment for accelerated attrition testing and determining indices like the Davison Index (DI) [26]. |

| Sintered Metal Filters | High-temperature, corrosion-resistant filters used in reactor systems to trap catalyst fines, prevent their loss, and protect downstream equipment [25]. |

| Particle Size Analyzer | Instrument (e.g., laser diffraction) for measuring the particle size distribution (PSD) of fresh and used catalysts, critical for diagnosing attrition. |

| XRF Spectrometer | Analytical instrument for performing elemental composition analysis on catalyst fines and bulk samples to determine the attrition mechanism [26]. |

Diagnostic and Experimental Workflows

Catalyst Attrition Diagnostic Pathway

Laboratory Attrition Testing Workflow

Bibliometric Analysis of Research Trends (2000-2024)

Catalyst deactivation and regeneration represent a critical field of study, directly impacting the efficiency, cost, and sustainability of industrial processes ranging from petroleum refining to pharmaceutical manufacturing. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and foundational methodologies for researchers working within this domain, framed by a comprehensive bibliometric analysis of research trends from 2000 to 2024. The analysis reveals a steadily growing publication output across three focal areas: catalyst coke (CC), catalyst stability and deactivation (CSD), and catalyst regeneration (CR), with 30,873, 44,834, and 1,987 research articles respectively published in English during this period [12]. This expanding knowledge base underscores the importance of standardized protocols and problem-solving resources to support ongoing research efforts in catalyst longevity and performance restoration.

Table 1: Global Research Output in Catalyst Deactivation and Regeneration (2000-2024)

| Research Focus | Total Publications (2000-2024) | Key Research Countries | Prominent Institutions | Primary Application Areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Coke (CC) | 30,873 | China, USA, Germany | University of Witwatersrand, Chinese Academy of Sciences | Petrochemicals, biomass conversion, environmental catalysis |

| Catalyst Stability & Deactivation (CSD) | 44,834 | USA, China, Japan | Stanford University, CNRS, Max Planck Society | Pharmaceutical manufacturing, energy processes, chemical synthesis |

| Catalyst Regeneration (CR) | 1,987 | Germany, USA, South Africa | University of Cambridge, MIT, University of Tokyo | Catalyst recycling, sustainable process design, economic optimization |

Source: Web of Science Database Analysis [12]

Table 2: Key Catalytic Processes with Associated Deactivation Challenges

| Industrial Process | Primary Catalyst Type | Dominant Deactivation Mechanism | Typical Regeneration Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry Reforming of Methane (DRM) | Ni, Pt, Rh-based | Carbon deposition, sintering, sulfur poisoning | Oxidation, hydrogenation, supercritical fluid extraction |

| Fluidized Catalytic Cracking (FCC) | Zeolite-based | Rapid coke formation, metal deposition | Continuous regeneration via combustion |

| Pharmaceutical Synthesis | Homogeneous/heterogeneous metal catalysts | Poisoning, thermal degradation | Chemical treatment, recrystallization |

| Biomass Conversion | Acidic zeolites, supported metals | Coke fouling, structural deterioration | Ozone treatment, controlled oxidation |

Source: Integrated from Multiple Studies [12] [28] [29]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Data Collection and Methodology

Q: What bibliometric databases and analysis tools are most appropriate for catalyst regeneration research?

A: For comprehensive bibliometric analysis in this field, we recommend:

- Primary Database: Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection, which provides high-quality metadata and citation data essential for accurate trend analysis [12] [30].

- Analysis Tools: VOSviewer (version 1.6.20) for creating and visualizing bibliometric networks, and CiteSpace for analyzing, detecting, and visualizing emerging trends and research frontiers [12] [31].

- Search Strategy: Implement a structured keyword approach with terms such as "coke deposition," "catalyst deactivation," "catalyst regeneration," and "carbon deposition" to ensure comprehensive coverage [12]. The search should be limited to document type (article) and language (English) for consistency, with data exported as "tab-delimited files" for analysis [12].

Q: How should research trends be categorized for meaningful analysis in this field?

A: Based on successful methodologies employed in recent analyses:

- Categorize publications into three primary domains: (1) catalyst coke formation and characterization, (2) catalyst stability and deactivation mechanisms, and (3) catalyst regeneration technologies [12].

- Within each category, conduct co-occurrence analysis of keywords to identify research hotspots and emerging topics [31].

- Analyze collaboration networks through institutional and country co-authorship patterns to understand knowledge dissemination pathways [30].

Experimental Protocols

Q: What is the standardized protocol for catalyst deactivation experiments?

A: For reproducible deactivation studies:

- Accelerated Deactivation Testing: Subject catalysts to extreme but controlled conditions (elevated temperatures, high contaminant concentrations) to simulate long-term deactivation in shorter timeframes [29].

- Time-on-Stream (TOS) Analysis: Monitor activity decay as a function of time under constant reaction conditions, typically using fixed-bed or fluidized-bed reactor systems [32].

- Mathematical Modeling: Apply deactivation functions such as power-law models (a = Atⁿ) or exponential decay models (a = e⁻ᵏᵈᵗ) to quantify deactivation rates [32].

- Post-reaction Characterization: Employ techniques including TPO (Temperature Programmed Oxidation) for coke quantification, BET surface area analysis, XRD for crystallinity assessment, and TEM for morphological changes [12] [29].

Q: What methodological framework should guide regeneration efficiency studies?

A: A comprehensive regeneration assessment should include:

- Activity Restoration Measurement: Compare catalytic activity pre-deactivation and post-regeneration using standardized test reactions relevant to the catalyst's application [12].

- Selectivity Analysis: Evaluate not only activity recovery but also selectivity restoration, as regeneration processes may alter the nature of active sites [12].

- Multiple Cycle Testing: Subject catalysts to successive deactivation-regeneration cycles to assess long-term regenerability and structural stability [12] [29].

- Environmental Impact Assessment: Quantify energy consumption and emissions associated with the regeneration process for sustainability evaluation [12].

Technical Troubleshooting

Q: How can hot spots and thermal degradation during coke combustion regeneration be mitigated?

A: Several strategies have proven effective:

- Staged Temperature Programming: Implement controlled temperature ramping with holding periods at intermediate temperatures to manage exothermicity [12].

- Diluted Oxidizing Agents: Use oxygen concentrations below 5% in inert gas to moderate combustion intensity and prevent runaway temperatures [12] [29].

- Alternative Oxidants: Employ ozone (O₃) or NOx instead of oxygen for low-temperature coke removal, particularly effective with ZSM-5 catalysts [12].

- Process Intensification Technologies: Implement microwave-assisted regeneration (MAR) or plasma-assisted regeneration (PAR) for more controlled energy input and reduced thermal stress [12].

Q: What approaches prevent irreversible deactivation in dry reforming of methane (DRM) catalysts?

A: For DRM catalysis, implement these anti-deactivation strategies:

- Active Metal Selection: Utilize noble metals (Rh, Ru, Pt) or appropriately promoted Ni catalysts with enhanced carbon resistance [29].

- Support Optimization: Employ supports with strong metal-support interaction (e.g., CeO₂, ZrO₂, MgAl₂O₄) to stabilize metal dispersion and provide oxygen mobility for carbon removal [29].

- Alkaline Promoters: Incorporate elements like K, Ca, or Mg to enhance CO₂ adsorption and gasification of surface carbon [29].

- Bimetallic Formulations: Develop alloy catalysts (e.g., Ni-Fe, Ni-Co) that exhibit synergistic effects for enhanced stability and reduced coking [29].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Catalyst Deactivation and Regeneration Studies

| Reagent/Catalyst | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| HZSM-5 Zeolite | Acid catalyst for hydrocarbon conversion | Coke formation studies, regeneration testing | Framework Si/Al ratio determines acidity and coking tendency |

| Ni/MgO | Model reforming catalyst | DRM deactivation mechanisms, sintering studies | MgO support provides basic sites for CO₂ adsorption |

| Fe₃O₄ Nanoparticles | Fenton-like catalyst, nanozyme | Biomedical applications, oxidation studies | Particle size controls catalytic activity and stability |

| Pd/Al₂O₃ | Hydrogenation catalyst | Poisoning studies, regeneration evaluation | Noble metal loading affects dispersion and susceptibility to poisoning |

| Ozone (O₃) | Mild oxidant for regeneration | Low-temperature coke removal from zeolites | Concentration and temperature critical to prevent framework damage |

| Supercritical CO₂ | Extraction solvent | Coke removal without thermal degradation | Pressure and temperature above critical point (31°C, 73.8 bar) |

Source: Compiled from Research Applications [12] [33] [29]

Workflow Visualization

Catalyst Regeneration Research Workflow

Catalyst Deactivation Mechanisms Classification

Regeneration Methodologies: From Conventional to Cutting-Edge Techniques

Catalyst deactivation due to coke deposition, the accumulation of carbonaceous material on the catalyst surface and within its pores, is a fundamental challenge in industrial catalytic processes. This deactivation leads to diminished activity, selectivity, and overall process efficiency [22] [12]. Oxidative regeneration, the process of removing coke by reacting it with oxidizing agents, is a critical strategy for restoring catalytic activity and extending catalyst lifespan. This technical guide explores the application of various oxidants—Air, O₂, O₃, and NOₓ—within the broader context of regeneration strategies for deactivated catalysts. It provides researchers and development professionals with troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols to effectively implement these regeneration techniques in both research and industrial settings, emphasizing the operational principles, trade-offs, and technical considerations for each method.

Oxidant Comparison and Selection Guide

Selecting the appropriate oxidant is crucial for efficient, economical, and catalyst-friendly regeneration. The optimal choice depends on the coke characteristics, catalyst composition, and process constraints. The table below provides a structured comparison of the primary oxidative agents.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Oxidants for Catalyst Regeneration

| Oxidant | Operational Mechanism | Typical Operating Conditions | Key Advantages | Key Limitations & Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air | Complete combustion of coke to CO₂ and H₂O [12]. | Medium to High (400-550°C) [12] | Low cost, high availability, simple process design [12]. | High exothermicity risk (hot spots, thermal damage) [3] [12] [34]. |

| O₂ (Pure) | Enhanced oxidation kinetics for faster coke removal. | Medium to High (Similar to air) | Higher efficiency and faster regeneration than air [12]. | Increased cost; higher risk of runaway reactions and thermal damage [12]. |

| O₃ (Ozone) | Low-temperature oxidative decomposition of coke via highly reactive radicals [12]. | Low (< 300°C) [12] | Prevents thermal sintering; effective for delicate catalyst structures [12]. | High cost of O₃ generation; potential safety hazards; complex handling [12]. |

| NOₓ | Functions as an oxygen carrier, participating in redox cycles on the catalyst surface [12]. | Medium | Can offer alternative reaction pathways and selectivity [12]. | Handling toxic gases; risk of leaving nitrogen-containing residues on the catalyst [12]. |

Troubleshooting Common Oxidative Regeneration Challenges

Despite its widespread use, oxidative regeneration can present several operational challenges. The following guide addresses common issues and provides targeted solutions for researchers and engineers.

FAQ 1: Why is there a loss of catalyst activity after oxidative regeneration, even when coke analysis shows successful removal?

- Problem: Incomplete recovery of catalytic activity.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Irreversible Structural Changes. High temperatures during regeneration, especially with air or O₂, can cause sintering, where active metal particles agglomerate and reduce the total active surface area [3].

- Troubleshooting: Implement strict temperature control and use a gradual temperature ramp-up during regeneration to minimize thermal stress [34]. Consider switching to a lower-temperature oxidant like O₃ if sintering is confirmed via particle size analysis (e.g., TEM, chemisorption) [12].

- Cause: Incomplete Contaminant Removal. The regeneration process may have removed carbonaceous coke but left behind other poisons like sulfur or heavy metals [3].

- Troubleshooting: Conduct a full post-regeneration characterization (e.g., XPS, elemental analysis) to identify residual contaminants. Adjust the regeneration protocol or implement pre-treatment steps (e.g., guard beds) to manage feed impurities in subsequent cycles [3].

FAQ 2: How can we control the risk of thermal damage and runaway reactions during coke combustion?

- Problem: Uncontrolled exothermic reaction during regeneration.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Inadequate Temperature Monitoring and Control. The combustion of coke is highly exothermic, and localized hot spots can rapidly escalate [12].

- Troubleshooting: Invest in advanced temperature monitoring systems with multiple points along the catalyst bed. Use diluted oxygen streams (e.g., air instead of pure O₂) and ensure proper quench system design and operation to manage bed temperatures [3] [35].

- Cause: High Coke Load. A very thick layer of coke can lead to a massive heat release upon ignition.

- Troubleshooting: For heavily coked catalysts, employ a controlled, slow heating rate and lower initial oxygen concentration to manage the burn-front progression [12].

FAQ 3: Why are toxic by-products like HCN and NOₓ formed during regeneration, and how can their emission be mitigated?

- Problem: Emission of hazardous gases during regeneration.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Nitrogen-containing Coke. The coke deposited on catalysts processing nitrogen-rich feeds contains heteroatoms like pyrrolic (N-5) and pyridinic (N-6) nitrogen. Upon oxidation, these can form HCN and NOₓ as intermediates [36].

- Troubleshooting: Optimize regeneration conditions, particularly oxygen concentration and temperature, to promote the complete oxidation of HCN to N₂ [36]. Consider post-combustion De-NOₓ technologies (e.g., SCR, SNCR) or specialized catalyst additives designed to control these emissions [36].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Temperature-Programmed Oxidation (TPO) for Coke Characterization

TPO is a fundamental technique for quantifying coke and understanding its oxidation behavior.

- Objective: To determine the amount of coke on a spent catalyst and profile its reactivity towards oxygen.

- Materials:

- Reactor: Fixed-bed quartz reactor.

- Gas Supply: 2-5% O₂ in He/Ar, high-purity He/Ar.

- Analysis: Mass Spectrometer (MS) or Non-Dispersive Infrared (NDIR) detector for CO₂ and CO.

- Temperature Controller: Programmable furnace.

- Methodology:

- Loading: Place 50-200 mg of spent catalyst in the reactor.

- Purge: Flush the system with inert gas (He/Ar) at room temperature.

- Ramp: Heat the reactor at a constant rate (e.g., 5-10°C/min) from room temperature to 800°C under the oxidizing gas mixture.

- Analysis: Monitor the effluent gas stream continuously with the MS or NDIR to detect the production of CO₂ and CO as a function of temperature.

- Data Interpretation: The resulting TPO profile (CO₂ signal vs. temperature) provides information on coke "burn-off" temperature. Multiple peaks indicate different types of coke (e.g., soft vs. hard coke), with lower temperature peaks corresponding to more reactive carbon forms [36].

Protocol: Laboratory-Scale Oxidative Regeneration with O₃

This protocol details a low-temperature regeneration method suitable for thermally sensitive catalysts.

- Objective: To regenerate a coked catalyst using ozone while minimizing thermal degradation.

- Materials:

- Ozone Generator: UV-light or corona discharge generator.

- Reactor: Fixed-bed reactor, preferably glass or corrosion-resistant metal.

- Ozone Destruct Unit: To safely decompose excess O₃.

- Gas Supply: O₂ source for the generator, carrier gas (e.g., He).

- Methodology:

- Setup: Connect the O₃ generator to the reactor inlet. Ensure all exhaust O₃ is routed through the destruct unit.

- Loading: Place the coked catalyst in the reactor.

- Reaction: Pass a stream of O₃ (typically 1-5% in O₂ or air) over the catalyst at a low temperature (e.g., 150-300°C) for a predetermined time [12].

- Post-treatment: After regeneration, purge the system with an inert gas to remove any residual O₃.

- Safety Note: Ozone is a powerful oxidant and toxic gas. All operations must be conducted in a well-ventilated fume hood, and equipment must be checked for leaks.

Diagram 1: O3 regeneration workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Successful experimental work in catalyst regeneration relies on a set of essential materials and analytical techniques.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Oxidative Regeneration Studies

| Item | Function / Purpose | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Spent/Coked Catalyst | The subject of the regeneration study. | Characterize coke content (TPO, TGA) and catalyst properties (surface area, porosity, active site density) before and after regeneration. |

| Oxidant Gases | Reactive agents for coke removal. | Air/ O₂: For standard combustion. O₃: For low-temperature regeneration. NO/NO₂: For studying alternative pathways [12]. Use with appropriate mass flow controllers. |

| Inert Gases (He, Ar, N₂) | System purging, creating inert atmosphere, carrier gas. | Essential for safety purges before/after regeneration and for use in analytical techniques like TPO. |

| Fixed-Bed Microreactor System | Core platform for conducting controlled regeneration experiments. | System should include precise temperature control, gas delivery, and often is integrated with analytical equipment. |

| Temperature-Programmed Oxidation (TPO) Setup | Quantifying coke and profiling its reactivity. | Typically couples a microreactor with a mass spectrometer or NDIR detector [36]. |

| Analytical Instruments: BET, XRD, TEM, XPS | Characterizing catalyst physical and chemical properties. | BET: Surface area/pore volume. XRD/TEM: Crystallite size and sintering. XPS: Surface composition and chemical state [3] [36]. |

Diagram 2: Coke oxidation pathway.

Troubleshooting Guide for Catalyst Deactivation

This guide addresses common catalyst issues in gasification and hydrogenation processes, framed within regeneration strategies for deactivated catalyst research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why has my catalyst lost activity after regeneration? A common issue is incomplete regeneration or exposure to high temperatures causing sintering, an often irreversible process where active metal particles agglomerate and reduce surface area [34] [2]. Ensure controlled temperature ramp-up during regeneration and verify the complete removal of contaminants like coke or sulfur [34] [3].

Q2: How can I diagnose the root cause of catalyst deactivation? Systematic characterization is essential. Key techniques and their applications are listed in the table below [2].

Table 1: Key Catalyst Characterization Techniques

| Technique | Acronym | Primary Function in Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Area Analysis | BET | Measures loss of active surface area, indicating sintering or fouling [2]. |

| Elemental Analysis | XRF / PIXE | Identifies foreign elements (poisons) deposited on the catalyst surface [2]. |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy | XPS | Detects chemical states of poisons on the catalyst surface [2]. |

| Temperature-Programmed Desorption | TPD | Determines the adsorption strength of species, indicating poisoning or fouling [2]. |

Q3: My catalyst is fouled by coke deposits. What is the standard regeneration protocol? Coke fouling is often addressed through controlled oxidative regeneration. This involves burning off the carbon deposits in an oxygen-containing atmosphere (e.g., air) at elevated temperatures [3]. Precise temperature control is critical to avoid thermal damage and sintering from the exothermic reaction [3].

Q4: When is catalyst regeneration not viable? Regeneration may be ineffective with severe irreversible sintering, certain strong poisonings (e.g., by heavy metals), or if the regeneration cost exceeds replacement [3]. In these cases, replacement with a new catalyst or recycling precious metals is recommended [3].

Q5: How can I prevent potassium poisoning from biomass feedstocks? Potassium, a common poison in biomass conversion, can deactivate Lewis acid sites. Research on Pt/TiO2 catalysts shows this poisoning can be reversed by water washing [9]. Mitigation strategies include feedstock pre-treatment and using guard beds [9].

Experimental Protocol for Root Cause Analysis

This methodology outlines the steps for diagnosing catalyst deactivation [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Catalyst Regeneration Research

| Material/Reagent | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Palladium (Pd) | Key component in dense metallic membranes for high-purity hydrogen separation from syngas [37]. |

| Ruthenium (Ru) | Promoter added to nickel catalysts to enhance activity and sulfur resistance in decomposition reactions [38]. |

| Alumina (Al₂O₃) & Ceria (CeO₂) | Common catalyst supports; Al₂O₃ can prevent agglomeration in gasification, while CeO₂-based supports can aid in redispersion of precious metals after sintering [3] [38]. |

| Guard Beds | Pre-reactor beds used to adsorb impurities like sulfur from feed streams, protecting the main catalyst from poisoning [2] [3]. |

| Potassium Carbonate (K₂CO₃) | A catalyst used in processes like supercritical water gasification (SCWG) of carbon-based feedstocks [38]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) Troubleshooting

Q: My SFE extraction yields are lower than expected. What could be the cause? A: Low yields in SFE often relate to solvent power or mass transfer issues. Key factors to check:

- Pressure and Temperature: Verify that your system pressure and temperature are within the optimal range for your target compound. For non-polar compounds, ensure pressure is sufficiently high (e.g., 300-400 bar for many oils). The "crossover phenomenon" means temperature increases can have opposite effects on yield depending on whether you are above or below the crossover pressure [39].

- Co-solvent Use: If extracting polar bioactive compounds, a co-solvent like ethanol is often necessary. Confirm the co-solvent percentage is optimized for your sample [40].

- Matrix Preparation: The raw material may require pre-treatment. Ensure your sample is properly ground and dried, as particle size and moisture content significantly impact diffusion and solubility [40].

- System Blockages: Check for blockages in the extraction vessel or tubing that may be restricting CO₂ flow.

Q: How can I improve the selectivity of my SFE process? A: Selectivity is a key advantage of SFE and can be enhanced by:

- Parameter Tuning: Precisely control pressure and temperature to exploit small differences in compound solubility [40].

- Sequential Extraction: Use a series of extraction steps with different parameters or solvents. SFE is often used first to extract oils, followed by Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE) to recover polar phenolics from the defatted biomass [40].

- Fractionation: Utilize on-line fractionation by employing separators at different pressures and temperatures to collect distinct compound fractions [40].

Q: I am concerned about safety when operating a high-pressure SFE system. What safeguards are in place? A: Industrial SFE systems are designed with multiple layers of safety:

- Certification: All components are certified for required pressures (e.g., PED in Europe, ASME in North America), and the entire assembly is certified by an independent body [41].

- Physical Protections: High-pressure pipes and fittings are placed behind protective stainless steel shields to protect the operator [41].

- Automated Safety Systems: The process control system often has SIL (Safety Integrity Level) 3 certification. This dedicated safety PLC can immediately halt the process, close valves, and isolate machine parts if a risk is detected [41].

Microwave-Assisted Regeneration (MAR) Troubleshooting

Q: The regeneration efficiency of my catalyst using MAR is inconsistent across cycles. Why? A: Inconsistent regeneration can stem from several factors:

- Hot Spot Formation: Microwaves can create localized "hot spots," leading to non-uniform heating. Ensure the catalyst bed is well-mixed and that the microwave cavity provides even exposure [42].

- Incomplete Contaminant Removal: If coke or poison is not fully removed in one cycle, it can lead to accelerated deactivation in the next. Confirm your MAR parameters (power, time, atmosphere) are sufficient for complete contaminant gasification. Coke can typically be removed with oxygen in 15-30 minutes at 300°C [43].

- Catalyst Sintering: While MAR is faster, excessively high power can still cause thermal degradation and metal sintering over multiple cycles, which is often irreversible. Monitor the catalyst's structural properties after each cycle [43].

Q: How does MAR compare to conventional thermal regeneration in terms of energy use? A: MAR is significantly more energy-efficient. A recent study on regenerating zeolite 13X for CO₂ capture found that MAR reduced energy consumption tenfold—0.06 kWh compared to 0.62 kWh for conventional heating—while also cutting regeneration time from 30 minutes to 10 minutes [42].

Q: My catalyst does not seem to heat effectively under microwaves. What is wrong? A: This is typically a material property issue. Effective microwave heating requires the catalyst or its support to be dielectric (lossy). Consider:

- Material Selection: Use catalyst supports like zeolites (e.g., 13X) that contain polar species (e.g., mobile Na⁺ ions) which couple well with microwave energy [42].

- Additives: Incorporating a microwave-susceptible material (e.g., graphitic carbon) into the catalyst mix can act as a heater, transferring heat to the active catalyst sites [42].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Microwave-Assisted Regeneration of Zeolite 13X

This protocol is adapted from a study investigating MAR for direct air CO₂ capture [42].

1. Objective: To regenerate a CO₂-saturated Zeolite 13X adsorbent and compare the efficiency of Microwave-Assisted Regeneration (MAR) against Conventional Thermal Regeneration.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- Fixed-Bed Reactor: Configured for microwave irradiation.

- Microwave Generator: Capable of precise power control (e.g., 300 W).

- Zeolite 13X: In pellet or powder form.

- Gas Supply: Synthetic air with ~400 ppm CO₂.

- CO₂ Analyzer: For measuring inlet and outlet gas concentrations.

- Thermocouple: To monitor bed temperature.

3. Experimental Procedure:

- Adsorption Saturation: Pack the fixed-bed reactor with Zeolite 13X. Expose the adsorbent to a continuous flow of synthetic air (400 ppm CO₂) at ambient temperature and pressure until the outlet CO₂ concentration equals the inlet concentration, indicating saturation.

- Microwave-Assisted Regeneration:

- Group 1: Subject the saturated zeolite bed to microwave irradiation at an optimized power of 300 W for 10 minutes. The bed temperature will reach approximately 350°C. No carrier gas is required.

- Parameter Optimization: Using a fresh saturated sample for each run, vary the microwave power (e.g., 200 W, 300 W, 400 W) and regeneration time (e.g., 5, 10, 15 min) to establish optimal conditions via statistical methods like ANOVA.

- Conventional Regeneration (for comparison):

- Group 2: Regenerate the saturated zeolite using a conventional furnace at 350°C for 30 minutes, typically with an inert purge gas.

- Performance Measurement: After each regeneration cycle, repeat the adsorption saturation step and measure the CO₂ adsorption capacity. Calculate the regeneration efficiency using the formula:

- Regeneration Efficiency (%) = (Adsorption capacity after regeneration / Initial adsorption capacity) × 100

Quantitative Data Comparison

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from a study comparing MAR and conventional regeneration for Zeolite 13X [42].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Regeneration Methods for Zeolite 13X

| Performance Metric | Microwave-Assisted Regeneration | Conventional Heating |