Strategies for Mitigating Catalyst Deactivation from Coking and Sintering: Mechanisms, Regeneration, and Stability Optimization

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of catalyst deactivation, focusing on the pervasive challenges of coking and sintering.

Strategies for Mitigating Catalyst Deactivation from Coking and Sintering: Mechanisms, Regeneration, and Stability Optimization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of catalyst deactivation, focusing on the pervasive challenges of coking and sintering. It explores the fundamental chemical mechanisms driving these processes, evaluates conventional and emerging regeneration technologies, and presents practical strategies for enhancing catalyst longevity. By integrating the latest research, including bibliometric trends and advanced mitigation approaches, this work serves as a strategic resource for researchers and development professionals seeking to design more durable and efficient catalytic systems for biomedical and industrial applications. The content bridges foundational science with application-oriented troubleshooting to address deactivation across various catalyst architectures.

Understanding the Enemy: Foundational Mechanisms of Catalyst Coking and Sintering

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in Catalyst Coking Experiments

FAQ 1: How can I determine if my catalyst is deactivating due to active site poisoning or physical pore blockage?

Answer: Distinguishing between these mechanisms requires a combination of characterization techniques. Active site poisoning occurs when coke molecules chemically bind to active sites, rendering them inaccessible for reaction. Pore blockage involves physical obstruction of catalyst pores by carbonaceous deposits, preventing reactant access to active sites deeper within the pore structure [1].

Diagnostic Protocol:

- Perform Temperature-Programmed Oxidation (TPO): Monitor CO₂ evolution during controlled temperature increase. Multiple distinct peaks indicate different types of coke (e.g., filamentous vs. graphitic), which suggest different deactivation mechanisms [2].

- Conduct Physisorption Measurements: Compare BET surface area and pore volume distributions between fresh and deactivated catalysts. Significant reduction in pore volume, especially in specific pore size ranges, indicates pore blockage [3] [4].

- Use Chemisorption Probes: Employ CO or H₂ chemisorption to quantify accessible active metal sites. A disproportionate loss of chemisorption capacity relative to surface area loss suggests active site poisoning [1].

- Analyze Kinetic Data: Measure reaction rates as a function of coke content. For pure site poisoning, activity typically decreases linearly with coke content, while pore blockage often shows exponential decay patterns [4].

Table 1: Characterization Techniques for Different Deactivation Mechanisms

| Technique | Active Site Poisoning Indicator | Pore Blockage Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| TPO | Single low-temperature CO₂ peak | Multiple CO₂ peaks at different temperatures |

| BET Surface Area | Minimal change relative to activity loss | Significant decrease in specific pore sizes |

| Chemisorption | Dramatic reduction in active site count | Reduced site count proportional to surface area loss |

| TEM/SEM | Thin, uniform coke layers on surfaces | Visible pore obstructions, carbon filaments |

FAQ 2: What are the most effective regeneration strategies for coke-deactivated catalysts?

Answer: Regeneration strategy selection depends on the coke type and catalyst stability. Traditional oxidation remains most common, but emerging techniques offer advantages for temperature-sensitive materials [2].

Regeneration Protocols:

Conventional Oxidation Method:

- Controlled Air Oxidation: Place deactivated catalyst in fixed-bed reactor. Heat gradually to 450-550°C under nitrogen. Introduce air diluted with nitrogen (2-5% O₂). Monitor temperature carefully to prevent hotspots exceeding 600°C that can damage catalyst structure [2].

- Stepwise Oxygen Increase: Begin with 1% O₂ in N₂ at 400°C, increasing to 5% O₂ after initial coke removal. Use online gas analyzer to monitor CO₂ production until baseline is stable [2].

Advanced Low-Temperature Methods:

- Ozone-Assisted Regeneration: For temperature-sensitive materials like ZSM-5, use 200-500 ppm ozone in oxygen at 150-250°C. Monitor for 2-6 hours until activity restored. This method preferentially removes hard-to-oxidize coke precursors [2].

- Supercritical CO₂ Extraction: Place catalyst in high-pressure cell. Pressurize to 150-300 bar with CO₂, heat to 40-80°C. Maintain for 1-4 hours with continuous flow for soluble coke species [2].

Table 2: Regeneration Methods for Different Coke Types

| Regeneration Method | Optimal Temperature Range | Coke Type Addressed | Potential Catalyst Damage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air Oxidation | 450-550°C | Amorphous & filamentous carbon | High (sintering above 600°C) |

| Ozone Treatment | 150-250°C | Polyaromatic/graphitic coke | Low |

| Supercritical CO₂ | 40-80°C | Soluble hydrocarbon deposits | Very Low |

| Hydrogenation | 300-400°C | Unsaturated carbon species | Medium |

Experimental Protocols for Coke Formation and Mitigation

Protocol 1: Accelerated Coking Test for Catalyst Screening

Purpose: Evaluate catalyst susceptibility to coking under controlled laboratory conditions.

Procedure:

- Reactor Setup: Load 0.5-1.0 g catalyst (60-80 mesh) into fixed-bed microreactor. Ensure uniform packing to avoid channeling.

- Pre-treatment: Activate catalyst under hydrogen or inert gas at specified activation temperature (typically 400-500°C) for 2 hours.

- Coking Reaction: Switch to reaction mixture containing 5-10% potential coke precursors (e.g., ethylene, propylene) in nitrogen at 500-600°C. Use weight hourly space velocity (WHSV) of 2-4 h⁻¹.

- Monitoring: Sample effluent gas periodically by GC analysis. Monitor pressure drop across catalyst bed to detect pore blockage.

- Termination: Stop experiment after predetermined time (typically 4-24 hours) or when conversion drops below 50% of initial value.

- Analysis: Cool reactor under nitrogen, recover catalyst for TPO, surface area, and elemental analysis [2] [4].

Protocol 2: Quantifying Coke Distribution in Catalyst Particles

Purpose: Determine spatial distribution of coke within catalyst particles to identify predominant deactivation mechanism.

Procedure:

- Sectioning: Carefully crush spent catalyst particles and separate by sieving to obtain different particle size fractions.

- Sequential Extraction: Use Soxhlet extraction with toluene for 24 hours to remove soluble coke precursors. Follow with dichloromethane for more refractory compounds.

- Temperature-Programmed Oxidation: Analyze each fraction separately using TPO with 5% O₂ in He, heating at 10°C/min to 900°C while monitoring CO₂.

- Elemental Analysis: Determine carbon content in each fraction using CHNS analyzer.

- Microtomy and TEM: For selected samples, prepare ultrathin cross-sections using microtome and analyze by TEM to visualize coke location [3] [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Coke Formation and Regeneration Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Diluted Oxygen (2-5% in N₂) | Controlled coke oxidation | Prevents runaway temperature during regeneration |

| Ozone Generator | Low-temperature oxidation | Suitable for temperature-sensitive materials like zeolites |

| Supercritical CO₂ System | Solvent extraction of coke | Effective for soluble hydrocarbon deposits |

| TPO Reactor System | Coke quantification and characterization | Identifies coke type by oxidation temperature |

| Model Coke Precursors (e.g., ethylene, propylene) | Accelerated coking studies | Provides reproducible coke formation conditions |

| Porous Model Catalysts | Fundamental mechanism studies | Controlled pore structures for isolation of variables |

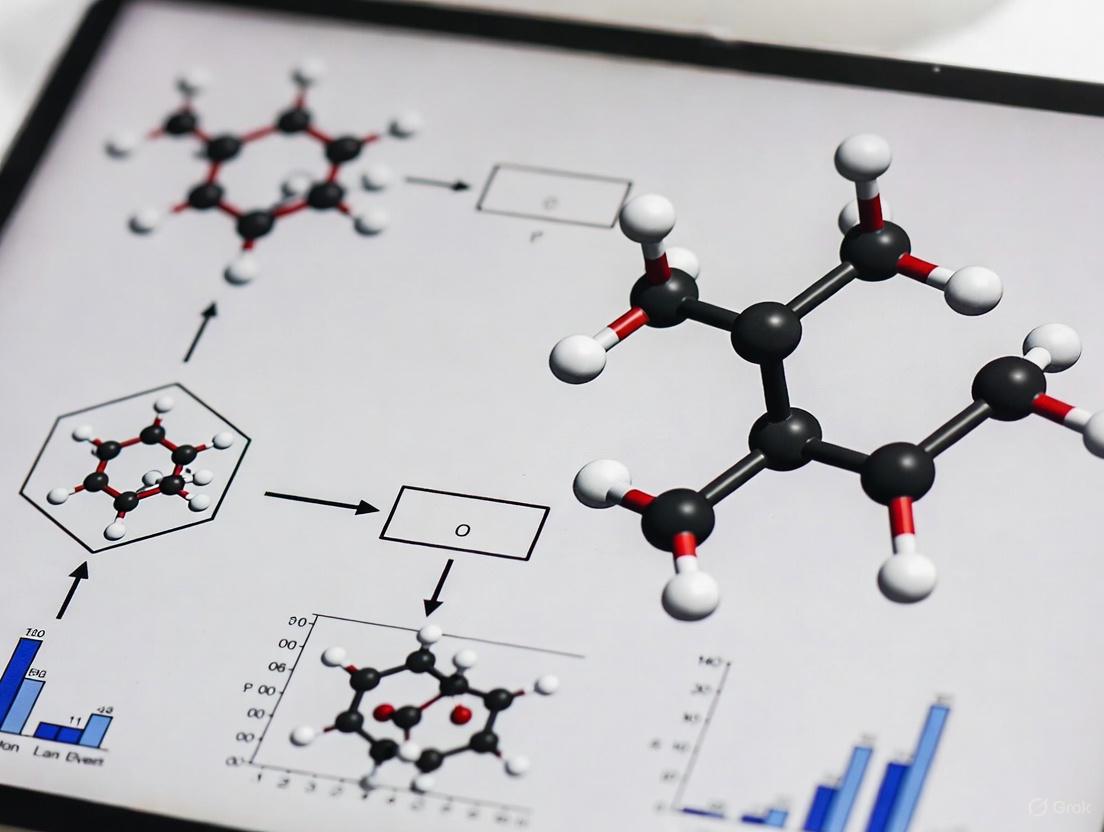

Visualization of Coke Formation Pathways and Diagnostic Approaches

Coke Formation Pathway

Coke Diagnosis Workflow

Thermodynamic and Kinetic Drivers of Metal Sintering and Particle Agglomeration

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers address metal sintering and particle agglomeration in catalytic applications, particularly within research focused on mitigating catalyst deactivation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary thermodynamic drivers behind particle agglomeration and sintering? Agglomeration and sintering are driven by the system's tendency to achieve a state of minimum free energy. This occurs primarily through:

- Reduction of Surface Energy: The process minimizes the total surface area and energy by replacing high-energy solid-vapor interfaces with lower-energy solid-solid interfaces [5] [6]. This is a dominant factor in sintering.

- Changes in Enthalpy and Entropy: The overall change in free energy (ΔG) is governed by the equation ΔG = ΔH - TΔS, where ΔH is the change in enthalpy (e.g., from binding energy or surface energy reduction) and ΔS is the change in entropy. For nanoparticles, the reduction in surface energy (a component of ΔH) is often the most significant driver [5].

2. What kinetic factors control the rate of sintering in metal catalysts? The kinetics of sintering are largely governed by atomic diffusion, which is highly dependent on several factors:

- Temperature: Atomic diffusion, whether through the lattice (volume diffusion) or along grain boundaries, relies heavily on temperature and typically follows an Arrhenius-type relationship [7] [6].

- Activation Energy: The energy barrier for diffusion dictates the sintering rate. For example, the activation energy for sintering ultrafine molybdenum powder was found to be 383.49 kJ/mol [7].

- Particle Size and Distribution: The rate of material transport is much higher for finer particles with high curvature. A uniform, fine particle size distribution can lead to faster pore elimination and densification [6].

3. How does sintering lead to catalyst deactivation? Sintering is a thermal degradation mechanism that causes a loss of active surface area in two main ways:

- Reduced Surface Area: The fusion of smaller particles into larger ones decreases the total catalytic surface area available for reactions [8].

- Phase Transformation: In some cases, the catalytic phases can shift into non-catalytic phases, further hindering the intended chemical reactions [8].

4. What operational conditions can accelerate sintering? Certain environments and impurities can significantly increase the sintering rate:

- High-Temperature Exposure: Operating above the catalyst's thermal threshold is a primary cause [8].

- Specific Atmospheres: The presence of steam or chlorine can accelerate the sintering process [8].

- Impurities: Alkali metals can speed up sintering, whereas oxides of Ba, Ca, or Sr can decrease the sintering rate [8].

5. How can I differentiate between agglomeration and sintering in my catalyst?

- Agglomeration involves particles clustering together, often through weak forces like van der Waals attraction. This can sometimes be reversed with sufficient energy input (e.g., ultrasonication) [9].

- Sintering involves the formation of strong metallic or ceramic bonds between particles via atomic diffusion at high temperature. This process is typically irreversible and leads to permanent growth of crystal grains [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Rapid Sintering of Catalyst at High Operating Temperatures

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inadequate Thermal Stability

- Cause: Operating Temperature Too High

- Solution: If possible, optimize the process to run at a lower temperature. Continuously monitor and control the temperature to avoid unexpected excursions [8].

- Cause: Presence of Sintering Promoters

- Solution: Use high-purity feedstocks to minimize contaminants like alkali metals. Alternatively, introduce sintering inhibitors, such as Ba or Ca oxides, into the catalyst formulation [8].

Problem: Particle Agglomeration in Liquid-Phase Reactions

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Dominance of Attractive Van der Waals Forces

- Solution: Modify the surface charge of the particles to introduce strong electrostatic repulsion. This can be achieved by adjusting the pH of the solution to move it away from the isoelectric point of the particles [9].

- Cause: High Particle Concentration

- Solution: Reduce the nanoparticle loading to increase the average distance between particles, thereby weakening the attractive potential [9].

- Cause: Lack of Steric Hindrance

- Solution: Use stabilizers or surfactants that adsorb onto the particle surface, creating a physical barrier that prevents particles from coming close enough to agglomerate [9].

Experimental Protocols for Analysis

Protocol: Analyzing Sintering Behavior via Dilatometry

This method tracks dimensional changes in a powder compact during heating to study sintering kinetics.

- Sample Preparation: Form a green body by pressing the catalyst powder into a well-defined shape (e.g., a bar or cylinder) [6].

- Instrument Setup: Place the sample in a dilatometer furnace. An probe rests on the sample to measure its change in length.

- Heating Cycle: Heat the sample at a controlled rate (e.g., 5-10°C/min) to a target temperature (e.g., 50-80% of the material's melting point) in a controlled atmosphere [6].

- Data Collection: Record the temperature and the corresponding change in length (shrinkage) of the sample in real-time.

- Data Analysis: Plot shrinkage versus temperature/time. The onset of shrinkage indicates the start of sintering. The shrinkage rate can be used to estimate activation energies for the process.

Protocol: Quantifying Agglomeration via Particle Size Distribution Analysis

This protocol compares the primary particle size to the agglomerated size to assess the degree of agglomeration.

- Sample Dispersion:

- For dry powders: Use a dry powder disperser on a laser diffraction particle size analyzer.

- For slurries: Prepare a dilute suspension in a suitable liquid (e.g., water, ethanol) and use ultrasonication to break up weak agglomerates.

- Measurement:

- Method A (Laser Diffraction): Measure the particle size distribution of the well-dispersed sample. This provides the size of agglomerates or primary particles, depending on the dispersion energy.

- Method B (BET Surface Area Analysis): Measure the specific surface area of the powder via gas adsorption. A lower surface area than expected for the primary particles indicates agglomeration or sintering.

- Calculation of Agglomeration Degree: Calculate the ratio of the agglomerate size (from laser diffraction after mild dispersion) to the primary particle size (from BET or electron microscopy). A ratio significantly greater than 1 indicates agglomeration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials and their functions in studying or mitigating sintering and agglomeration.

| Research Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Stabilized Zirconia | A high-temperature-resistant ceramic used as a catalyst support to inhibit sintering of active metal phases [10]. |

| Barium Oxide (BaO) | An inhibitor added to catalyst formulations to decrease the sintering rate of the active material [8]. |

| Silica (SiO₂) Coating | Used to encapsulate nanoparticles, imparting a negative surface charge that prevents agglomeration in aqueous environments via electrostatic repulsion [9]. |

| Zinc Oxide (ZnO) Guard Bed | A pretreatment material placed upstream of the main catalyst to adsorb poisons like H₂S, mitigating deactivation that can exacerbate sintering [8]. |

| Hydrogen-Donor Solvents | Chemicals like tetralin used in heavy oil upgrading to suppress coke formation, which is often linked to thermally induced sintering [10]. |

Visualization of Mechanisms and Workflows

Sintering and Agglomeration Drivers

Catalyst Deactivation Troubleshooting Workflow

Quantitative Data on Sintering

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from research on the sintering of ultrafine molybdenum powders, illustrating the impact of process parameters [7].

| Sintering Temperature | Holding Time | Relative Density Achieved | Hardness (HV1.0) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1600 °C | 8 h | Data Not Provided | 183.60 |

| 1800 °C | 4 h | 98.83 % | Data Not Provided |

Additional Quantitative Insight: The activation energy for sintering was determined to be 383.49 kJ/mol, and for grain boundary migration, it was 3.29 kJ/mol [7].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the fundamental mechanisms of coking and sintering?

Coking and sintering are two primary, yet distinct, mechanisms of catalyst deactivation.

- Coking (or Fouling): This is the physical deposition of carbonaceous residues on the catalyst surface and within its pores. These deposits, which can amount to 15-20% of the catalyst's weight, physically block active sites and hinder the movement of reactants and products [11]. The nature of coke varies, from soft, hydrogen-rich polymers to hard, graphitic carbon structures [12].

- Sintering (Thermal Degradation): This is the loss of active surface area due to exposure to high temperatures. It causes the small, dispersed nanoparticles that constitute the active phase of the catalyst to agglomerate into larger, thermodynamically more stable particles. This process reduces the total number of active sites available for the reaction [12].

FAQ 2: How do coking and sintering interact to accelerate catalyst deactivation?

Coking and sintering do not occur in isolation; they can interact synergistically to cause more severe and rapid deactivation than either mechanism alone.

- Sintering Promotes Coking: The agglomeration of metal particles during sintering can create new, often less stable, crystalline facets that are more prone to catalyzing side reactions leading to carbon formation [11] [2]. Furthermore, sintering reduces the number of active sites, which can lead to increased residence time of reactants on the remaining sites, thereby increasing the likelihood of undesirable decomposition and coking reactions.

- Coking Exacerbates Thermal Damage: Carbon deposits can have low thermal conductivity, acting as an insulating layer. During coke combustion for regeneration, this can lead to the formation of localized "hot spots" where the temperature drastically exceeds the bulk gas temperature. These extreme local temperatures can severely accelerate the sintering of the underlying catalyst material, causing permanent damage [2].

FAQ 3: What experimental techniques are used to diagnose co-occurring coking and sintering?

Diagnosing this interplay requires a combination of techniques to characterize both the carbon deposits and the metallic active phase.

Table: Key Experimental Techniques for Diagnosing Coking and Sintering

| Technique | Acronym | Primary Function | Key Information Obtained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermogravimetric Analysis | TGA | Measures weight changes vs. temperature | Quantifies coke burn-off; estimates coke reactivity [12]. |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy | TEM | High-resolution imaging | Visualizes coke morphology (filaments, encapsulating) and measures metal particle size distribution [12]. |

| X-ray Diffraction | XRD | Determines crystalline structure | Identifies crystalline phases of catalyst and coke; estimates crystallite size growth due to sintering [12]. |

| Temperature-Programmed Oxidation | TPO | Profiles oxidation activity vs. temperature | Identifies different types of coke based on their oxidation temperatures [2]. |

| Physisorption | BET | Measures surface area and porosity | Quantifies loss of surface area and pore volume from blocking by coke and/or sintering [11]. |

FAQ 4: What strategies can mitigate the combined deactivation from coking and sintering?

Mitigation requires a holistic approach targeting both mechanisms simultaneously through catalyst design and process control.

- Catalyst Design: Using promoters (e.g., adding ZnO to Cu-based catalysts) can trap impurities like sulfur that catalyze coking [11]. Employing supports with Strong Metal-Support Interaction (SMSI) can anchor metal nanoparticles, preventing their migration and sintering at high temperatures [12].

- Process Optimization: Carefully controlling reaction temperature and feedstock purity is crucial. Lower temperatures can slow sintering rates, while removing coke precursors from the feed can reduce fouling [11].

- Advanced Regeneration: Emerging techniques like Low-Temperature Ozone Treatment can selectively remove coke without generating the exothermic heat that causes sintering, unlike traditional air combustion [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Rapid activity decline during high-temperature hydrocarbon reaction. Question: Is the deactivation due to pore blockage, active site loss, or both?

Diagnosis Protocol:

- Post-reaction Analysis: Conduct a TGA/TPO experiment on the spent catalyst. Multiple peaks in the oxidation profile indicate different types of carbon deposits (e.g., amorphous vs. graphitic) [2].

- Structural Inspection: Perform TEM and XRD on the fresh and spent catalysts. TEM will reveal the location and morphology of coke (e.g., filamentous vs. encapsulating) and provide direct images of metal particle size changes. XRD will show if the crystal structure of the active phase has changed or if graphitic carbon peaks are present [12].

- Surface Area Measurement: Use BET physisorption to measure the loss of surface area. A significant loss in micropore volume suggests pore blocking by coke, while a general loss in surface area can also indicate sintering [11].

Interpretation:

- High coke content + enlarged metal particles → Synergistic Coking & Sintering.

- High coke content + stable metal particle size → Coking is primary cause.

- Low coke content + enlarged metal particles → Sintering is primary cause.

Solution:

- If synergistic deactivation is confirmed, consider modifying the catalyst formulation to improve both coke resistance (e.g., by tuning acidity) and thermal stability (e.g., via a refractory support). Also, review process conditions to avoid temperature excursions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Materials for Studying and Mitigating Coking and Sintering

| Material / Reagent | Function / Application | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Cerium Oxide (Ceria) | Promoter / Support | Enhances oxygen mobility, facilitating gasification of surface carbon deposits before they polymerize into coke. Improves thermal stability of supported metals [13]. |

| Zinc Oxide (ZnO) | Guard / Trapper | Often used as a guard bed or co-catalyst to chemically trap sulfur poisons (e.g., H₂S) from the feed, preventing sulfur-induced coking and site blockage [11]. |

| Tungsten Oxide (WO₃) | Promoter / Stabilizer | Improves the dispersion of active metals (e.g., on Fe₂O₃ catalysts) and enhances surface acidity, which can be tuned to control reaction pathways and reduce coking. Also improves thermal stability [13]. |

| Refractory Oxides (e.g., Al₂O₃, SiO₂) | Catalyst Support | Provide high surface area and stable porous structure to disperse active metal particles. Their high melting point makes them resistant to structural collapse and pore degradation under high-temperature conditions [11] [12]. |

| Ozone (O₃) | Regeneration Agent | An advanced oxidant for low-temperature coke removal. It reacts with carbon deposits exothermically but at much lower temperatures than O₂, minimizing the risk of thermal runaway and sintering during regeneration [2]. |

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected pathways of coking and sintering and a general workflow for their experimental investigation.

Diagram 1: Synergistic Deactivation Cycle and Investigation Workflow. The red path shows the sintering pathway, the green shows the coking pathway, and the blue shows the experimental workflow. The yellow nodes represent key drivers or process changes.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How do the pore structure and acidity of a zeolite influence coke formation and deactivation? The pore structure and acidity are fundamental in controlling coke-induced deactivation. The characteristics and kinetics of coke formation are strongly influenced by the zeolite structure and acidity properties [14]. Coke formation typically involves stages like hydrogen transfer at acidic sites, dehydrogenation of adsorbed hydrocarbons, and gas polycondensation [2]. Theoretically, coke affects catalyst performance by poisoning active sites (overcoating them) and clogging the pores, making active sites inaccessible to reactants [2]. The specific type of coke produced depends on both the catalyst and the reaction parameters [2].

2. What are the primary strategies for designing zeolites to be more resistant to deactivation? Key strategies focus on modulating the hierarchical structure and the acidic sites:

- Hierarchical Structure Modulation: Introducing mesopores or macropores can create a multistage pore size system (hierarchical zeolite), which greatly improves molecular transport and diffusion rates, leading to better adsorption and catalytic behavior and potentially reducing pore blockage [15]. Strategies include using soft templates (e.g., surfactants, macromolecular polymers) or hard templates, post-synthesis atom removal, and using crystal seeds [15].

- Acidity Modulation: Regulating the distribution, density, and type of acidic sites (Brønsted Acid Sites, BAS and Lewis Acid Sites, LAS) is essential [15]. This can be achieved through in situ synthesis methods by changing raw materials or doping ions, or through post-synthesis treatments [15]. Since each framework aluminum (AlF) atom implies a BAS, regulating AlF also regulates the BAS density [15].

3. Can a deactivated zeolite catalyst be regenerated, and what methods are available? Yes, deactivation from coking is often reversible [2] [8]. Regeneration is both practically and economically valuable [2].

- Conventional Methods: Coke can be removed through oxidation using air/O₂, O₃, or NOₓ, or through gasification with CO₂ or H₂O vapor [2] [8]. However, the exothermic nature of coke combustion can lead to hot spots and damage the catalyst [2].

- Emerging Methods: Advanced techniques like supercritical fluid extraction (SFE), microwave-assisted regeneration (MAR), and plasma-assisted regeneration (PAR) can eliminate coke at milder temperatures, increasing regeneration efficiency while minimizing damage [2]. In cases where active components are leached (e.g., titanium in TS-1), vapor-phase supplementation has been shown to successfully restore catalyst selectivity [16].

4. Besides coking, what other mechanisms cause zeolite deactivation?

- Sintering: This is a thermal degeneration that leads to a reduced catalytic surface area and support area. It can be accelerated by steam, chlorine, and alkali metals [8].

- Poisoning: This is the reversible or irreversible chemical deactivation by contaminants, leading to loss of activity, stability, and selectivity. For example, potassium can poison Lewis acid sites on catalysts [17], and sulfur is a common poison for metal catalysts [8].

- Loss of Active Components: In some reactions, the acidic environment or specific reactants can cause the leaching of critical framework elements, such as titanium, leading to deactivation [16].

5. How does water in the reaction environment affect the acidity and activity of zeolites? The presence of water significantly alters the state of Brønsted acid sites (BAS). At low water content (1-2 water molecules per BAS), the acidic protons are shared between the zeolite and water. At higher water contents (n > 2), the protons become solvated within a localized water cluster, forming hydronium ions adjacent to the BAS site [18]. This transition impacts the acid strength and catalytic reactivity, with the free energy of the system being dominated by enthalpy at low water loadings and entropy at higher loadings [18].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Rapid Activity Loss Due to Coke Deposition

Problem: Your zeolite catalyst shows a rapid decline in conversion or selectivity during a hydrocarbon conversion reaction.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Confirm Coking: Use Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) to quantify the amount of coke deposited on the spent catalyst. A significant mass loss upon combustion in air confirms coke presence [2] [14].

- Check Process Conditions:

- Evaluate Catalyst Design:

- Acidity: Strong acid sites promote coking. Consider using a zeolite with a lower density of strong acid sites (e.g., higher Si/Al ratio) or passivate strong sites with modifiers [15] [14].

- Porosity: Micropores are easily blocked. Use a hierarchically structured zeolite with mesopores to facilitate the diffusion of coke precursors out of the catalyst, reducing blockage [15].

Regeneration Protocol (Oxidative Regeneration with Air):

- Purge: After reaction, purge the reactor with an inert gas (e.g., N₂) to remove any residual flammable reactants or products.

- Oxidation: Introduce a diluted air stream (e.g., 2-5% O₂ in N₂) at a low temperature (e.g., 350°C).

- Temperature Ramp: Slowly increase the temperature (e.g., 1-5°C/min) to a maximum of 450-550°C. A slow ramp rate is critical to manage the exothermic heat of coke combustion and prevent damaging hot spots [2].

- Hold: Maintain the maximum temperature until the CO₂ concentration in the effluent gas returns to baseline.

- Cool: Cool down in an inert atmosphere before subsequent use.

Issue 2: Permanent Deactivation and Loss of Surface Area

Problem: After multiple regeneration cycles or exposure to harsh conditions, the catalyst does not fully recover its activity.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Check for Sintering: Use N₂ physisorption to measure the BET surface area and pore volume of the fresh and regenerated catalyst. A permanent loss indicates sintering and structural collapse [8] [19].

- Identify Poisoning: Techniques like X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) or elemental analysis can detect the presence of poisons (e.g., S, K) on the catalyst surface [8] [17]. For example, sulfur poisoning by H₂S is a known issue for metal-containing catalysts [8].

- Mitigate Sintering:

- Avoid overheating the catalyst beyond its thermal stability limit. Monitor temperature carefully during exothermic reactions and regenerations [8].

- Operate in dry atmospheres where possible, as steam accelerates sintering [8].

- Consider catalyst formulations with structural promoters (e.g., Ba, Ca, Sr oxides) that lower the sintering rate [8].

Issue 3: Activity Loss in Aqueous-Phase Reactions

Problem: Catalyst performance is lower than expected in reactions involving water or steam.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Understand Acidity Modulation: Recognize that water solvates the Brønsted acid sites, converting them into hydronium ions (H₃O⁺). The catalytic activity of these hydronium ions is still high in confined zeolite pores [18].

- Select Appropriate Zeolite: Choose a zeolite topology with suitable hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity. Hydrophobic, high-silica zeolites may be preferable for certain aqueous-phase reactions to minimize competitive water adsorption [18].

- Optimize Water Content: The impact of water is concentration-dependent. The protonation state and acid strength can be tuned by the amount of water present [18].

Experimental Data and Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Common Zeolite Deactivation Mechanisms and Mitigation Strategies

| Deactivation Mechanism | Primary Cause | Observable Effect | Mitigation Strategy | Key Experimental Characterization Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coking / Fouling [2] [8] [14] | Deposition of carbonaceous species from side reactions. | - Pore blockage- Active site covering | - Optimize reaction T/P to minimize side reactions [8].- Design hierarchical pore structure [15].- Regenerate via controlled oxidation [2]. | - TGA (coke quantification)- N₂ Physisorption (surface area/pore loss) |

| Sintering [8] | Exposure to high temperatures, especially in steam. | - Loss of surface area- Crystallite growth | - Use thermal-stable supports/additives (e.g., Ba, Ca oxides) [8].- Avoid overheating and steam [8]. | - BET Surface Area analysis- XRD (crystallite size) |

| Poisoning [8] [17] | Strong chemisorption of contaminants (e.g., S, K, heavy metals). | - Permanent loss of active sites | - Use guard beds (e.g., ZnO for S-removal) [8].- Pretreat feedstock to remove impurities [8].- Water washing for reversible poisoning (e.g., K) [17]. | - XPS, EDX (elemental surface analysis)- ICP-MS (bulk elemental analysis) |

| Leaching of Active Species [16] | Acidic environment or specific reactants causing framework element loss. | - Change in product selectivity- Permanent activity loss | - Replenish active components via post-synthesis treatment (e.g., vapor-phase Ti supplementation) [16]. | - XPS, ICP-MS (to detect element loss) |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Zeolite Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Brief Explanation | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soft Templates (e.g., Surfactants like CTAB) [15] | Creating hierarchical mesopores in zeolites during synthesis. | Organic molecules self-assemble into micelles, around which the zeolite crystallizes, creating ordered mesopores after calcination. | Can be costly and may require removal via calcination, which can impact the framework [15]. |

| Hard Templates (e.g., Carbon nanoparticles) [15] | Creating hierarchical mesopores in zeolites. | Solid particles are embedded during zeolite synthesis; subsequent removal by combustion leaves behind mesoporous voids. | Allows for precise pore size control but involves an additional synthesis step for template removal [15]. |

| Ammonia (NH₃) / Pyridine | Probe molecules for acidity characterization via FTIR or TPD. | These basic molecules adsorb onto acid sites (Brønsted and Lewis). FTIR identifies site type, while TPD quantifies acid strength and density. | Standard method for qualitative and quantitative acidity measurement. |

| Platinum (Pt) / Nickel (Ni) | Active metal components for bifunctional catalysis (e.g., in DFMs for ICCU) [20]. | Provides hydrogenation/dehydrogenation functionality. Often dispersed on a support like Al₂O₃ or TiO₂. | Can be susceptible to sintering and poisoning (e.g., S, K) [8] [17]. |

| Titanium Tetrachloride (TiCl₄) | Reagent for post-synthesis regeneration of TS-1 zeolites [16]. | In vapor-phase supplementation, it re-inserts titanium into silanol nests created by Ti leaching, restoring active sites. | Requires high-temperature and controlled conditions for effective implantation [16]. |

Experimental Workflow and Deactivation Pathways

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Diagnosing Zeolite Deactivation

Diagram: Zeolite Deactivation Pathways and Interrelationships

Catalyst deactivation presents a fundamental challenge across numerous industrial processes, compromising performance, efficiency, and sustainability. This technical support center, framed within the broader thesis on mitigating catalyst deactivation from coking and sintering research, provides structured guidance for researchers confronting these issues in experimental settings. Between 2000 and 2024, research has steadily intensified, with bibliometric analysis revealing approximately 30,873 publications on "catalyst coke," 44,834 on "catalyst stability and deactivation," and 1,987 specifically on "catalyst regeneration" [2]. This growing body of literature underscores the field's importance while highlighting the necessity for clear, actionable troubleshooting resources. The following sections synthesize these bibliometric insights into practical experimental guidance, detailed protocols, and visual workflows to assist researchers in identifying, understanding, and resolving common catalyst deactivation problems.

Bibliometric analysis of catalyst deactivation literature reveals distinct productivity trends and focal points within the field. The data, sourced from Web of Science, illustrates a steady upward trajectory in publication output across all key categories from 2000 through early 2024 [2].

Table 1: Publication Output in Catalyst Deactivation Research (2000-May 2024)

| Research Focus Category | Total Publications | Sample Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Coke (CC) | 30,873 | "Coke," "Coking," "Coke deposition," "Carbon deposition" |

| Catalyst Stability & Deactivation (CSD) | 44,834 | "Catalyst deactivation," "Catalyst stability," "Deactivation mechanism" |

| Catalyst Regeneration (CR) | 1,987 | "Catalyst regeneration," "In situ regeneration," "Regeneration of catalysts" |

Network analysis of author keywords identifies "graph theory," "functional connectivity," "fMRI," "connectivity," "organization," "brain networks," "resting-state fMRI," "cortex," "small-world," and "MRI" as the most frequent terms, highlighting the interdisciplinary and methodological character of this research domain [21]. This analysis, utilizing tools like VOSviewer and CiteSpace, helps map the intellectual structure and evolving frontiers of the field [2] [22].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Problems & Solutions

This section addresses frequently encountered issues in catalyst deactivation experiments, providing diagnostic questions and evidence-based solutions grounded in recent research.

FAQ 1: Why has my catalyst's activity rapidly declined during a hydrocarbon conversion reaction?

- Diagnosis: Rapid activity loss is often symptomatic of coke fouling. Carbonaceous deposits physically block active sites and pore channels, preventing reactant access [2] [8].

- Experimental Confirmation:

- Measure catalyst mass change post-reaction; a significant increase suggests coke formation.

- Perform Temperature-Programmed Oxidation (TPO) to characterize the type and burn-off temperature of the coke.

- Conduct surface area and porosity analysis (e.g., BET method) to quantify the loss of accessible surface area [2].

- Mitigation Strategies:

FAQ 2: My catalyst shows a gradual and irreversible loss of surface area and activity. What is the cause?

- Diagnosis: This is characteristic of thermal sintering, a process where catalyst nanoparticles agglomerate into larger crystals, reducing the total active surface area [8].

- Experimental Confirmation:

- Use Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) or X-ray Diffraction (XRD) to compare the particle size distribution of fresh and spent catalysts. An increase in average particle size confirms sintering.

- Mitigation Strategies:

- Stabilize with Supports: Employ thermally stable supports like alumina, silica, or cerium-zirconia mixed oxides.

- Utilize Structural Promoters: Incorporate additives like Ba, Ca, or Sr oxides, which have been shown to decrease sintering rates [8].

- Control Atmosphere: Avoid moist and chlorine-containing atmospheres, as they accelerate sintering [8].

FAQ 3: How can I distinguish between catalyst poisoning and coking?

- Diagnosis:

- Poisoning involves strong chemisorption of specific contaminants (e.g., S, K, Pb, As) onto active sites, selectively destroying their functionality [17] [23] [8]. It is often specific to the chemical nature of the poison and active site.

- Coking is a more physical blockage by carbon deposits, affecting site accessibility and often leading to pore plugging [2].

- Experimental Differentiation:

- Regeneration Test: Attempt to burn off coke in a controlled oxygen atmosphere (e.g., 2% O2 in He). Activity recovery suggests coking. Poisoning is often irreversible without specific treatments (e.g., water washing for potassium [17]).

- Surface Analysis: Techniques like X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) can detect the presence of poisonous elements (S, K, etc.) on the spent catalyst surface [23].

FAQ 4: My regenerated catalyst never fully recovers its initial activity. Why?

- Diagnosis: Incomplete regeneration can result from several factors:

- Solutions:

- Milder Regeneration: Explore advanced regeneration techniques like ozone (O3) treatment or supercritical fluid extraction, which can remove coke at lower temperatures and prevent thermal damage [2].

- Prevention: Focus on operational strategies and catalyst formulations that minimize the formation of hard-to-remove coke in the first place.

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies for Deactivation Studies

Protocol for Accelerated Catalyst Deactivation Testing

Principle: Simulate long-term operational deactivation in a condensed timeframe to rapidly screen catalyst durability and identify failure modes [17].

Workflow:

- Catalyst Pre-treatment: Activate the catalyst in a fixed-bed reactor under specified gas flow (e.g., H2 for reduction).

- Introduction of Poison/Precursor: Introduce a controlled concentration of a known poison (e.g., SO2 for sulfur poisoning, potassium salts for alkali poisoning [23]) or coking precursor (e.g., olefins) into the reactant stream.

- Accelerated Aging: Run the reaction at elevated temperatures (e.g., 50-100°C above standard operating temperature) to intensify deactivation kinetics.

- Periodic Activity Monitoring: At regular intervals, pause the aging process and standardize reaction conditions to measure catalytic activity and selectivity.

- Post-mortem Analysis: Characterize the spent catalyst using techniques like TPO, BET, TEM, and XPS to determine the dominant deactivation mechanism [17] [23].

Diagram 1: Accelerated Deactivation Testing Workflow

Protocol for Catalyst Regeneration via Controlled Coke Oxidation

Principle: Remove carbonaceous deposits through controlled gasification with oxygen to restore catalytic activity, while carefully managing exothermic heat to prevent sintering [2].

Workflow:

- Spent Catalyst Unloading: Unload the deactivated catalyst from the reactor, ensuring an inert atmosphere to prevent uncontrolled pyrophoric oxidation.

- Oxidative Regeneration: Place the catalyst in a controlled atmosphere furnace or reactor. Slowly ramp the temperature (e.g., 2-5°C/min) under a dilute oxygen stream (e.g., 2% O2 in N2).

- Temperature Monitoring: Carefully monitor the bed temperature. A sudden temperature "kick" indicates the exothermic combustion of coke. The maximum temperature should be kept below the catalyst's sintering threshold.

- Burn-off Completion: Hold at the final temperature until CO/CO2 evolution in the off-gas ceases, indicating complete carbon removal.

- Post-Regeneration Conditioning: Cool the catalyst in an inert atmosphere. Often, a final reduction step (in H2) is required to re-reduce any metal oxides formed during regeneration before returning to service [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Deactivation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Zeolite-based Catalysts (e.g., HZSM-5) | Acidic microporous catalysts widely used in hydrocarbon transformations; excellent model systems for studying coking and regeneration [2] [8]. |

| Supported Metal Catalysts (e.g., Pt/TiO2, Ni/Al2O3) | Model catalysts for studying sintering and poisoning mechanisms. Pt/TiO2 is a key system for understanding metal-support interactions and poison (e.g., K) deposition [17]. |

| Dilute Oxygen Mixtures (e.g., 2% O2 in N2) | Essential for safe and controlled regeneration studies, preventing runaway exotherms during coke oxidation that can sinter the catalyst [2]. |

| Ozone (O3) Generator | Provides a source of ozone for low-temperature regeneration studies, enabling coke removal without thermal damage [2]. |

| Model Poison Solutions (e.g., KNO3, (NH4)2SO4) | Used to synthetically poison catalysts in a controlled manner to study specific poisoning mechanisms (e.g., K poisoning of acid sites [17] [23]). |

| Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA) | Critical instrument for quantifying coke content (via mass gain) and studying coke combustion kinetics (via TPO) [2]. |

Research Gaps and Future Pathways

Bibliometric analysis not only maps existing knowledge but also illuminates critical gaps for future exploration. Key research needs identified in the literature include:

- Holistic Deactivation Understanding: Many studies focus on specific catalysts or single deactivation mechanisms. A significant gap exists in comprehensively integrating knowledge across multiple deactivation pathways (coking, sintering, poisoning) and regeneration routes to develop universal principles [2].

- Environmental Impact of Regeneration: The environmental implications and trade-offs associated with different regeneration methods are often overlooked and require systematic evaluation [2].

- Advanced Regeneration Techniques: While traditional oxidation is common, emerging methods like supercritical fluid extraction, microwave-assisted regeneration, and plasma-assisted regeneration show promise for lower-temperature, more efficient reactivation but need further development [2].

- Predictive Stability Models: There is a pressing need for multiscale, realistic computational models to demystify catalyst deactivation and, more importantly, predict catalyst stability for long-term operation [17].

Combating Deactivation: Regeneration Methodologies and Anti-Coking Catalyst Design

Technical FAQ: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: What are the primary indicators that my catalyst requires regeneration? A noticeable decline in catalytic activity and selectivity is the primary indicator. In industrial steam methane reforming (SMR), this often manifests as an abnormal increase in reactor pressure drop, which can be caused by excessive carbon deposition (coking) blocking catalyst pores and gas flow channels. Other signs include the development of localized hot spots and changes in product gas composition, such as reduced hydrogen yield [24].

FAQ 2: How do I choose between oxidation, gasification, and hydrogenation for coke removal? The choice depends on the type of carbon species present on your deactivated catalyst.

- Oxidation using air or oxygen is highly effective for removing amorphous carbon but requires careful temperature control to avoid catalyst damage from runaway exothermic reactions [24] [25].

- Gasification with steam (H₂O) or carbon dioxide (CO₂) is a milder alternative that helps prevent over-heating. It is particularly suited for removing graphitic carbon deposits [24].

- Hydrogenation with H₂ is most effective for less organized, reactive carbon forms. It gasifies carbon into methane (CH₄) and is less likely to damage the catalyst's active metal phase compared to oxidation [25].

FAQ 3: My catalyst's activity is not fully restored after regeneration. What could be the cause? This is often due to irreversible deactivation mechanisms that occur alongside coking. The most common is sintering, where high temperatures (either during reaction or regeneration) cause the growth of small, active metal particles into larger, less active ones. Other causes include permanent poisoning by impurities like sulfur or chlorine, or a loss of mechanical strength leading to catalyst powdering [24].

FAQ 4: What are the key parameters to monitor during oxidative regeneration? Precise control of temperature and oxygen concentration is critical. A gradual increase in temperature and the use of diluted oxygen (e.g., 1-2% in an inert gas) are recommended to manage the heat released from burning off carbon deposits, thereby preventing thermal damage to the catalyst [25].

FAQ 5: How can I prevent coking in my SMR experiments? Operational strategies are key. Maintain a high steam-to-carbon ratio in the feed to thermodynamically suppress carbon-forming reactions. Using promoted catalysts (e.g., with potassium) can also enhance resistance to coking by altering the surface acidity and improving carbon gasification [24].

Troubleshooting Guide for Regeneration Techniques

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid Temperature Spikes during Oxidation | Overly concentrated O₂ feed leading to uncontrolled, rapid combustion of carbon. | Dilute the O₂ stream with N₂. Implement a controlled, ramped temperature program to manage reaction rate [25]. |

| Incomplete Carbon Removal | Regeneration temperature is too low, or gas flow is insufficient to reach all deposits. | Optimize temperature within the safe operating window. Ensure proper gas distribution and consider a hold time at the target temperature [24]. |

| Catalyst Activity Declines After Multiple Regeneration Cycles | Progressive sintering of active metal particles (e.g., Ni) with each high-temperature cycle. | Lower the regeneration temperature if possible. Consider a final "re-reduction" step after carbon burn-off to re-disperse the active metal [24]. |

| Low Hydrogen Purity in Hydrogenation Regeneration | High concentration of methane and other gases in the product stream. | This may indicate the presence of highly reactive carbon. Optimize the H₂ flow rate and temperature to favor complete conversion to CH₄, which can then be purged [26]. |

| Pressure Drop Increase Post-Regeneration | Catalyst particle agglomeration or fragmentation due to harsh regeneration conditions. | Verify that temperature and gas composition stay within manufacturer recommendations. Avoid thermal shocks [24]. |

Quantitative Data on Regeneration Techniques

Table 1: Comparison of Conventional Regeneration Techniques for Coked Catalysts

| Technique | Operating Agents | Typical Temperature Range | Key Advantages | Key Limitations & Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidation | Air, O₂ (often diluted) | 450°C - 550°C | Highly effective; simple implementation; fast reaction kinetics. | High risk of thermal damage and sintering from exothermic heat; can oxidize active metal [24] [25]. |

| Gasification | Steam (H₂O), CO₂ | 700°C - 900°C | Milder than O₂; avoids metal oxidation; steam reforms heavy hydrocarbons/tar. | Endothermic, requiring energy input; slower kinetics; high temp can still promote sintering [24] [27]. |

| Hydrogenation | H₂ | 300°C - 500°C | Low-temperature process; minimizes thermal damage; reduces metal oxides. | High cost of H₂; can be less effective on graphitic carbon; may form methane [25] [26]. |

Table 2: Characterization Techniques for Pre- and Post-Regeneration Analysis

| Characterization Technique | Information Gained | Application in Regeneration |

|---|---|---|

| Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) | Quantifies amount and burn-off temperature of carbon. | Determines optimal regeneration temperature and confirms carbon removal efficiency [24]. |

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | Identifies crystalline phases, measures metal crystallite size. | Detects sintering (crystallite growth) and phase changes in support or active metal [24]. |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Reveals surface morphology, carbon nanostructures, and physical defects. | Visualizes carbon filaments, pore blockages, and surface degradation [24]. |

Experimental Protocol: Regeneration of a Coked SMR Catalyst

This protocol outlines a standard procedure for regenerating a nickel-based steam methane reforming catalyst deactivated by coke deposition, integrating techniques discussed in recent literature [24] [25].

Objective: To remove carbon deposits from a coked catalyst via controlled oxidation and restore catalytic activity while minimizing structural damage.

Materials and Equipment:

- Fixed-bed reactor system with temperature-controlled furnace

- Mass flow controllers for gases (N₂, air)

- Thermocouple for internal temperature monitoring

- Off-gas analyzer (e.g., for CO/CO₂)

- Coked catalyst sample (e.g., Ni/Al₂O₃ from SMR)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- System Purge: Load the coked catalyst into the reactor. Seal the system and purge with an inert gas (N₂) at a high flow rate (e.g., 100 mL/min) for 30 minutes at room temperature to displace any residual process gases.

- Controlled Heating under Inert Atmosphere: Begin heating the reactor to a safe initial oxidation temperature (e.g., 400°C) at a slow ramp rate (e.g., 5°C/min) under continuous N₂ flow (50 mL/min). This stabilizes the system.

- Diluted Oxidation: Once the temperature stabilizes at 400°C, introduce a carefully regulated stream of diluted air (1-2% O₂ in N₂). Monitor the off-gas for CO and CO₂, which indicate the onset of carbon combustion.

- Temperature Ramping and Hold: Gradually increase the reactor temperature to a target of 500°C at a very slow ramp rate (1-2°C/min) while maintaining the diluted O₂ flow. The slow ramp prevents runaway reactions. Hold the temperature at 500°C until the CO₂ concentration in the off-gas returns to baseline levels, signaling complete carbon removal. This may take several hours.

- Cool-down and Final Purge: Stop the air flow and switch back to pure N₂. Allow the reactor to cool slowly to room temperature under the N₂ blanket to prevent re-adsorption of oxygen or moisture on the freshly regenerated, active surface.

Safety Notes:

- Always use diluted O₂ for the initial oxidation step.

- Closely monitor the temperature to detect any sudden exotherms. Have a plan to switch to pure N₂ if the temperature rises too rapidly.

- Ensure proper ventilation as CO, a toxic gas, is a product of incomplete carbon oxidation.

Regeneration Technique Selection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting an appropriate regeneration technique based on catalyst properties and deactivation characteristics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Catalyst Regeneration Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Regeneration Research |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Gases (N₂, O₂, H₂, CO₂) | Used as regeneration agents and inert purges. Purity is critical to avoid catalyst poisoning. |

| Nickel-Based Catalyst (Ni/Al₂O₃) | A standard model catalyst for SMR and coking studies. Often promoted with K or Mg to enhance stability [24]. |

| Oxygen Carriers (e.g., BaFe₂O₄) | Used in chemical looping processes for partial oxidation and in-situ generation of pure H₂, which can aid regeneration cycles [26]. |

| Potassium Carbonate (K₂CO₃) | A common promoter/additive that improves catalyst resistance to coking and can enhance carbon gasification rates [24] [26]. |

Microwave-Assisted Regeneration (MAR)

FAQ: Microwave-Assisted Regeneration

Q1: Why does microwave heating sometimes cause damage to my catalyst or filter substrate?

A1: Damage is often due to uneven heating and "hot spot" formation, leading to thermal stress. Microwave energy deposition is inherently uneven and depends on the system's geometry and the material's dielectric properties [28]. For filters, this can cause areas of incomplete regeneration alongside spots of excessive exothermal heat release, which damages the substrate [28]. To mitigate this, ensure the microwave cavity is designed to promote a uniform field, and if possible, use a rotating platform or wave-stirring mechanisms to redistribute energy [28].

Q2: My catalyst doesn't seem to absorb microwave energy well. How can I improve heating efficiency?

A2: Heating efficiency depends on the material's dielectric loss factor (ε''). Materials with high loss factors (like diesel soot) are strong absorbers, while many ceramics (like cordierite) are transparent to microwaves [28]. If your catalyst is a weak absorber, consider:

- Adding a Microwave Susceptor: Introduce a secondary material with a high dielectric loss factor (e.g., specific carbon forms or silicon carbide) to absorb energy and heat the catalyst indirectly.

- Optimizing Field Frequency and Power: Adjust the microwave parameters (power, exposure time) to match your material's specific dielectric properties [28].

Experimental Protocol: Microwave Regeneration of Zeolite 13X for CO₂ Capture

This protocol is adapted from a study comparing microwave and conventional heating for regenerating a zeolite 13X fixed-bed reactor after CO₂ adsorption from air [29].

1. Objective: To regenerate a CO₂-saturated zeolite 13X adsorbent using microwave irradiation and evaluate its efficiency compared to conventional thermal regeneration.

2. Materials:

- Reactor System: Fixed-bed quartz reactor.

- Microwave System: Microwave generator with adjustable power (e.g., 300 W).

- Adsorbent: Zeolite 13X pellets, saturated with ~400 ppm CO₂ under ambient conditions.

- Analysis: Gas analyzer to measure desorbed CO₂ concentration.

3. Methodology: 1. Adsorption: Pass a gas stream with approximately 400 ppm CO₂ through the fixed bed of zeolite 13X at ambient temperature and pressure until saturation is achieved [29]. 2. Microwave Regeneration: * Place the saturated fixed-bed reactor into the microwave cavity. * Apply microwave irradiation at 300 W for 10 minutes. No carrier gas or external preheating is required. The temperature will reach approximately 350°C due to dielectric heating [29]. * Monitor the released CO₂ with the gas analyzer. 3. Conventional Regeneration (for comparison): * Place the saturated reactor in a conventional furnace. * Heat to 350°C for 30 minutes, typically with a carrier gas flow [29]. 4. Analysis: Calculate regeneration efficiency and measure the adsorption capacity of the regenerated zeolite over multiple cycles (e.g., three adsorption/desorption cycles).

4. Key Parameters & Data: The table below summarizes the quantitative outcomes from the cited study [29].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Zeolite 13X Regeneration Methods

| Regeneration Method | Optimal Conditions | Regeneration Efficiency | Energy Consumption | Adsorption Capacity Loss (after 3 cycles) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microwave Heating | 300 W, 10 min (~350°C) | 95.26% | 0.06 kWh | ~9% |

| Conventional Heating | 350°C, 30 min | 93.90% | 0.62 kWh | Comparable to microwave |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Microwave Regeneration

Table 2: Essential Materials for Microwave-Assisted Regeneration Experiments

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Fixed-Bed Reactor (Quartz) | Holds the catalyst/sorbent. Quartz is often used as it is transparent to microwaves. |

| Mono-mode or Multi-mode Microwave Cavity | Generates and contains the electromagnetic field for heating. Mono-mode offers more precise control for small-scale research. |

| Dielectric Property Analyzer | Characterizes the dielectric constant (ε') and loss factor (ε'') of materials to predict their microwave absorption potential [28]. |

| Infrared Pyrometer/Thermocouple | Measures temperature during microwave irradiation without interfering with the field. |

| Silicon Carbide (SiC) | A common microwave susceptor used to indirectly heat materials that are poor microwave absorbers. |

Plasma-Assisted Regeneration

FAQ: Plasma-Assisted Regeneration

Q1: What is the main advantage of using non-thermal plasma (NTP) for catalyst regeneration in reactions like Dry Reforming of Methane (DRM)?

A1: The primary advantage is the ability to activate stable molecules under mild conditions. NTP operates at low bulk gas temperatures (often below 1000 K) while generating high-energy electrons that create reactive species (radicals, ions, excited molecules) [30]. This avoids the high temperatures (≥700 °C) required in thermal catalysis, which often cause catalyst sintering. The plasma effectively mitigates sintering and carbon deposition, extending catalyst life [30].

Q2: How should I integrate the catalyst with the plasma reactor for the best results?

A2: The integration method significantly impacts performance. There are two primary configurations [30]:

- In-Plasma Catalysis (IPC): The catalyst is placed directly within the plasma discharge zone. This offers strong synergistic effects but can be complex.

- Post-Plasma Catalysis (PPC): The catalyst is placed downstream of the plasma discharge. The catalyst interacts with the reactive intermediates generated by the plasma. This is often simpler to implement.

For DRM, the IPC configuration generally shows better performance due to the more intimate contact between the plasma-generated species and the catalytic active sites [30].

Experimental Protocol: Plasma-Assisted Dry Reforming of Methane (DRM)

This protocol outlines the setup for a Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) plasma reactor to regenerate and maintain catalyst activity during DRM [30].

1. Objective: To convert CH₄ and CO₂ into syngas using a plasma-catalytic system, minimizing carbon deposition and catalyst deactivation.

2. Materials:

- Plasma Reactor: Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) reactor, consisting of a high-voltage electrode, a ground electrode, and a dielectric barrier (e.g., quartz tube).

- Power Supply: High-voltage AC power supply.

- Catalyst: Ni-based or noble metal (e.g., Pt, Ru) catalysts are common, often supported on Al₂O₃ or CeO₂.

- Gases: CH₄, CO₂ (feedstock), and optionally Ar or He as a carrier gas.

- Analysis: Gas chromatograph (GC) for quantifying CH₄ and CO₂ conversion and syngas (H₂/CO) ratio.

3. Methodology: 1. Reactor Setup: Pack the catalyst within the DBD reactor's discharge zone (for IPC configuration). Connect the gas lines and power supply [30]. 2. Reaction: * Introduce the reactant gas mixture (CH₄:CO₂) at a set flow rate (e.g., 20-50 mL/min). * Apply high voltage to initiate the plasma discharge. The discharge power is a critical parameter (e.g., 30-100 W). * Maintain the reaction at room temperature or slightly elevated temperatures. 3. Analysis: Use online GC to sample the effluent gas and calculate conversion rates and selectivity. Monitor for carbon deposition via post-reaction characterization (e.g., TPO, TEM).

4. Key Parameters & Data: The table below summarizes the general performance of plasma-catalytic DRM based on the reviewed literature [30].

Table 3: Typical Performance of Plasma-Catalytic DRM

| Parameter | Typical Range/Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CH₄ Conversion | 30% - 80% | Highly dependent on catalyst, power, and feed flow rate. |

| CO₂ Conversion | 25% - 75% | Usually lower than CH₄ conversion due to reverse water-gas shift reaction. |

| H₂/CO Ratio | < 1.0 | The syngas ratio is typically less than 1, which is suitable for certain chemical syntheses. |

| Energy Efficiency | Variable | A key challenge; optimization is needed to improve the energy cost per molecule converted. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Plasma-Assisted Regeneration

Table 4: Essential Materials for Plasma-Assisted Catalysis Experiments

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| DBD Reactor & HV Power Supply | The core system for generating non-thermal plasma at atmospheric pressure. |

| Dielectric Material (e.g., Quartz) | Acts as a barrier between electrodes, stabilizing the discharge and preventing arcing. |

| Ni-based Catalyst | A common and cost-effective catalyst for DRM; active but can be prone to carbon deposition. |

| Noble Metal Catalysts (Pt, Ru) | More expensive but often show higher activity and better resistance to coking. |

| Gas Chromatograph (GC) | Essential for quantifying reactant conversion and product selectivity in real-time. |

Supercritical Fluid Regeneration

Note: While the search results confirm that Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) is recognized as an emerging regeneration method [25], they do not provide specific experimental protocols or quantitative data for catalyst regeneration in this context. The following section is based on general principles of the technology.

FAQ: Supercritical Fluid Regeneration

Q1: Why would I use a supercritical fluid for regeneration instead of a conventional solvent?

A1: Supercritical fluids, particularly supercritical CO₂ (scCO₂), offer a unique combination of liquid-like solvating power and gas-like diffusivity and low viscosity [25]. This allows for:

- Penetration into Microporous Structures: Efficient extraction of coke precursors and contaminants from the smallest catalyst pores.

- Reduced Energy Consumption: The regeneration process often occurs at lower temperatures than thermal methods, preserving the catalyst's structural integrity.

- Environmental Safety: scCO₂ is non-toxic, non-flammable, and easily separable from the extracted solutes.

Q2: What are the main limitations of this technology?

A2: The primary challenges are high initial investment in pressure-rated equipment and the optimization of process parameters (pressure, temperature, co-solvents) for specific catalyst-contaminant systems [25]. It may not be economically viable for all applications compared to established thermal methods.

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Guides

This section addresses common experimental challenges in developing catalysts resistant to deactivation. The following FAQs provide targeted solutions based on recent research.

FAQ 1: How can I enhance the oxygen activation capacity of my supported metal catalyst to prevent coking?

Answer: Coking, or carbon deposition, is a common deactivation mechanism where carbonaceous species block active sites and pores [31] [2]. A proven strategy is to use a reducible oxide support, such as CeO₂ (ceria), and enhance its functionality with single-atom promoters.

- Root Cause: Coking often proceeds through hydrogen transfer at acidic sites, dehydrogenation of adsorbed hydrocarbons, and gas polycondensation [2]. Without efficient oxygen species to gasify these carbon precursors, they polymerize into inert coke.

- Solution: Incorporate single-atom zirconium (Zr) promoters into the CeO₂ support. Recent studies show that synthesizing CeO₂ with atomically dispersed Zr (Zr1-CeO2) via an atom-trapping method creates an asymmetric Zr1-O-Pt1 structure when used to support Pt nanoparticles [32].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Synthesis: Prepare the Zr1-CeO2 support using the atom-trapping method to incorporate Zr cations into the CeO2 lattice, ensuring atomic dispersion without forming ZrO2 nanoclusters [32].

- Characterization: Use X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS), including EXAFS, to confirm the absence of Zr-Zr bonds and quantify the coordination number of oxygen atoms around Zr (approximately 4-5), confirming single-site dispersion [32].

- Testing: Evaluate catalytic performance in oxidation reactions (e.g., CO or propane oxidation). The Pt/Zr1-CeO2 catalyst has demonstrated a four-fold increase in Turnover Frequency (TOF) and significantly lower T50 (temperature for 50% conversion) compared to Pt/CeO2, due to enhanced activation of both surface lattice oxygen and chemisorbed molecular oxygen [32].

FAQ 2: What are the primary causes of activity loss in Pd-based catalysts during continuous CO2 hydrogenation, and how can I mitigate them?

Answer: In continuous processes like CO2 hydrogenation to formate, catalyst deactivation is often linked to the physical degradation of the active metal.

- Root Cause: Comprehensive characterization of fresh versus spent Pd/AC (Palladium on Activated Carbon) catalysts identified sintering and leaching of Pd nanoparticles as the primary deactivation mechanisms [33]. Sintering is a thermal degradation process where metal particles agglomerate, reducing the active surface area [31] [34] [2].

- Solution: Optimize process conditions and consider robust catalyst design.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Stability Testing: Conduct a long-term stability test in a trickle-bed reactor. Monitor formate productivity over time (e.g., a 20-hour test showed a 20% decline in productivity) [33].

- Post-Reaction Characterization: Systematically compare fresh and spent catalysts using:

- N₂ Physisorption: To confirm that pore structure and surface area of the support remain unchanged, ruling out pore blockage as a major deactivation route [33].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): To visually observe changes in Pd nanoparticle size distribution, providing direct evidence for sintering [33].

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) & XAS: To analyze the chemical state and local coordination of Pd, helping to identify leaching or oxidation [33].

- Mitigation: Avoid excessive operating temperatures. The cited study found more severe deactivation at 150°C compared to 120°C [33]. Using a support with stronger metal-support interactions (SMSI) can also help stabilize metal nanoparticles against sintering.

FAQ 3: My catalyst is deactivating rapidly. How can I model this deactivation kinetics for process optimization?

Answer: Accurate deactivation models are essential for reactor design and predicting catalyst lifespan [35]. The choice of model depends on the deactivation mechanism.

- Root Cause: Deactivation can be selective or non-selective, and its rate depends on process conditions, catalyst type, and contaminants [35].

- Solution: Apply a suitable mathematical deactivation model. The table below summarizes common models.

Table 1: Common Mathematical Models for Catalyst Deactivation Kinetics

| Model Type | Mathematical Form | Applicability | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-on-Stream (TOS) [35] | a(t) = e^(-α*t) or a(t) = t^(-n) |

Systems with fast deactivation (e.g., FCC). Does not account for temperature or coke content. | α: deactivation coefficient; n: decay order |

| Power Law Model [35] | -da/dt = k_d * a^n a = 1/(1 + k_d * t) (for n=2) |

Broad applicability. Can be integrated into reactor models. | k_d: deactivation rate constant; n: deactivation order |

| Coke-Dependent Model [35] | a(t) = f(C_coke) |

Deactivation primarily by coking (e.g., fluidized catalytic cracking). | C_coke: coke content on catalyst |

- Experimental Protocol:

- Data Collection: Run the catalytic reaction over an extended time-on-stream (TOS) and measure the reaction rate or conversion at regular intervals.

- Activity Calculation: Calculate instantaneous activity as

a(t) = r(t) / r(t=0), wherer(t)is the reaction rate at timet[35] [34]. - Model Fitting: Fit the collected activity-versus-time data to the proposed models in Table 1. The model with the best fit (e.g., highest R² value) most accurately describes your deactivation kinetics.

- Parameter Estimation: Determine the deactivation rate constants (

k_d,α) from the fitted model. These parameters are crucial for simulating reactor performance over the catalyst's lifetime [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential materials and their functions for engineering robust catalysts, as featured in the cited research.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Developing Coke- and Sintering-Resistant Catalysts

| Reagent / Material | Function in Catalyst Engineering | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Ceria (CeO₂) Support | A reducible oxide that provides mobile lattice oxygen, facilitating the gasification of carbon precursors before they form coke (Mars-van Krevelen mechanism) [32]. | Used as a support for Pt nanoparticles; its oxygen storage capacity is key for oxidation reactions [32]. |

| Zirconium (Zr) Precursor (e.g., Zr nitrate) | A single-atom promoter. When atomically dispersed in CeO₂, it creates a unique Zr1-O-Pt1 structure that enhances the activation of both lattice and molecular oxygen [32]. | Incorporation into CeO₂ via atom-trapping led to a ~4x increase in TOF for Pt-catalyzed CO oxidation [32]. |

| Palladium on Activated Carbon (Pd/AC) | A benchmark heterogeneous catalyst for hydrogenation reactions. The AC support provides high surface area for metal dispersion [33]. | Used in continuous CO₂ hydrogenation; its deactivation via Pd sintering and leaching was systematically studied [33]. |

| Activated Carbon (AC) Support | A high-surface-area support with microporous structure. It maximizes metal dispersion but may be susceptible to pore blockage by coke [2]. | Served as the support for Pd during continuous hydrogenation; its pore structure was found to be stable despite reaction conditions [33]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflow Visualization

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in the troubleshooting guides.

Protocol: Synthesizing and Characterizing a Single-Atom Promoted Catalyst

Objective: To synthesize a CeO₂ support with atomically dispersed Zr promoters and load Pt active sites, then characterize the local structure [32].

Materials: Cerium precursor (e.g., Ce nitrate), Zirconium precursor (e.g., Zr oxynitrate), Platinum precursor (e.g., Tetraammineplatinum(II) nitrate).

Procedure:

- Support Synthesis (Atom-Trapping):

- Impregnate CeO₂ powder with an aqueous solution of the Zr precursor to achieve the desired loading (e.g., 2 wt%).

- Dry and calcine at high temperature (e.g., 800°C in air) to drive the diffusion and trapping of Zr atoms into the CeO₂ lattice.

- Metal Deposition:

- Impregnate the Zr1-CeO2 support with an aqueous solution of the Pt precursor.

- Dry and calcine at a moderate temperature (e.g., 500°C) to form oxidized Pt species.

- Catalyst Reduction:

- Reduce the catalyst in a flow of H₂ at a suitable temperature (e.g., 300°C for 3 hours) prior to reaction testing [33].

- Critical Characterizations:

- X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS): Perform at the Zr K-edge and Pt L3-edge. Analyze the Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (EXAFS) to confirm the absence of Zr-Zr or Pt-Pt coordination shells, proving atomic dispersion. Use XANES to determine oxidation states [32].

- HAADF-STEM: Image the catalyst to visually confirm the absence of Zr or Pt nanoparticles [32].

- CO Chemisorption: Measure metal dispersion and estimate average particle size on the reduced catalyst [33].

Protocol: Analyzing Catalyst Deactivation in a Continuous Reactor

Objective: To evaluate the stability of a catalyst and identify deactivation mechanisms during continuous operation [33].

Materials: Catalyst, reactor system (e.g., trickle-bed, fixed-bed), reagents.

Procedure:

- Reactor Setup: Load the reduced catalyst into a continuous reactor (e.g., a trickle-bed reactor for hydrogenation).

- Stability Test: Operate the reactor at fixed conditions (temperature, pressure, feed composition) for an extended period (e.g., 20-100 hours). Continuously monitor product stream composition to track conversion/yield over time.

- Post-Mortem Analysis:

- N₂ Physisorption: Compare the BET surface area and pore volume of spent and fresh catalysts to check for pore blockage or structural collapse [33].

- Electron Microscopy (TEM/SEM): Analyze particle size distributions of the active metal on fresh and spent catalysts to quantify sintering [33].

- Spectroscopy (XPS/XAS): Investigate changes in the chemical state and coordination environment of the active metal to identify leaching, oxidation, or poisoning [32] [33].

- Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): Measure the amount of coke deposited on the spent catalyst by burning it off in air [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Catalyst Deactivation Issues and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Catalyst Deactivation from Coking and Sintering

| Problem Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Methods | Solution & Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid activity loss in Ni-based catalysts during acetylene semi-hydrogenation. | Formation of inactive NiOx species due to Ni interaction with support hydroxyl groups [36]. | H2-TPR-MS, in situ FT-IR, CO-DRIFTS [36]. | Modify support surface to weaken metal-support hydroxyl interaction [36]. |

| Insufficient intrinsic activity and selectivity in Ni-SACs for CO2 electroreduction (CO2RR). | Suboptimal electronic structure of Ni single atoms weakens *COOH binding [37]. | Electrochemical analysis, computational modeling. | Implement long-range coordination engineering via Cl/S doping in higher-order coordination shells (≥2) [37]. |

| Carbon deposition (coking) on Ni catalysts during dry reforming of methane (DRM). | Methane cracking and Boudouard reaction on Ni active sites [38]. | TEM, TPO (Temperature Programmed Oxidation). | Use La2O3 support to promote coke resistance via La2O2CO3 intermediate formation; enhance Metal-Support Interaction (MSI) [38]. |

| Agglomeration & Sintering of single-atom sites under operational conditions. | Weak metal-support interaction; thermodynamic instability [39]. | HAADF-STEM, operando spectroscopy. | Construct robust substrate and strong metal-support interaction; optimize active site coordination environment [39]. |

| Performance degradation of SACs in oxygen reduction/evolution reactions (ORR/OER). | Dissolution of metal atoms, corrosion of carbon support, particle agglomeration [40]. | Accelerated stress testing, in situ electrochemical IR spectroscopy. | Coordination environment tuning (e.g., Ni-N4); use stable graphitic carbon supports [40]. |

Advanced Deactivation Mechanisms and Mitigation