Validating Machine Learning Catalyst Predictions: Bridging AI Models and Experimental Data for Drug Discovery

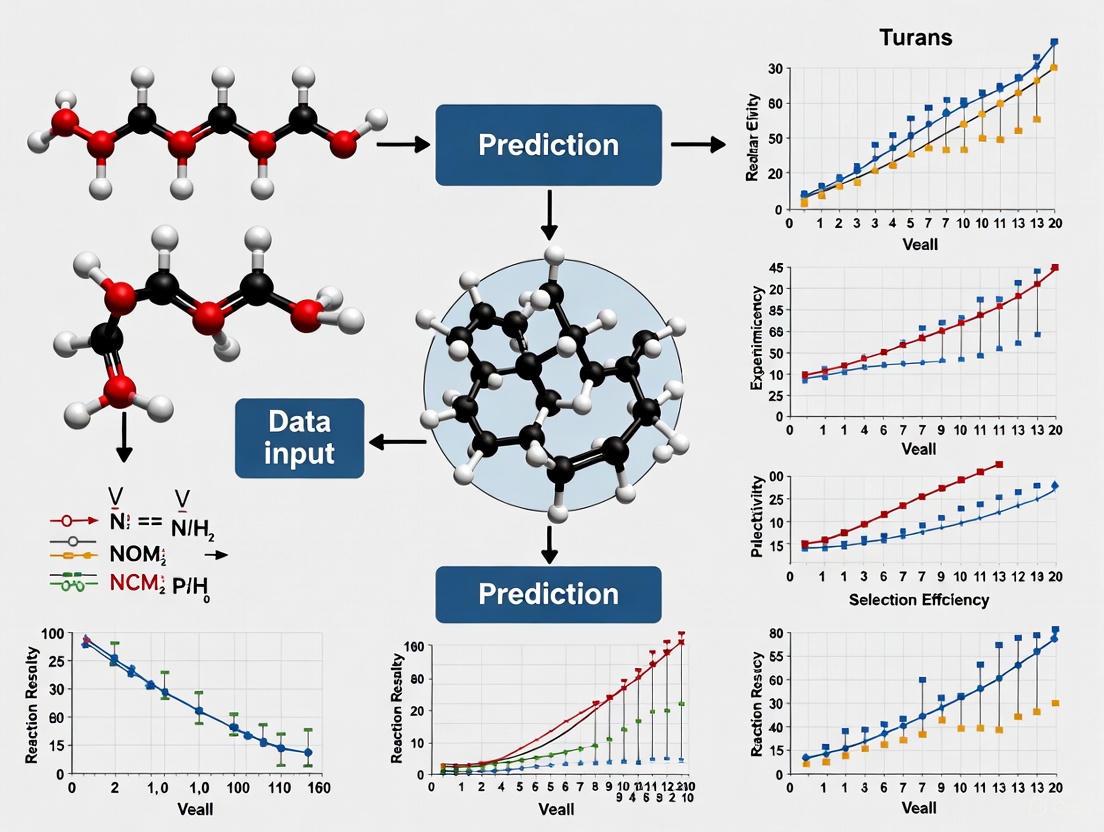

This article explores the critical process of validating machine learning (ML) predictions in catalyst design with experimental data, a key advancement for accelerating drug discovery and development.

Validating Machine Learning Catalyst Predictions: Bridging AI Models and Experimental Data for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the critical process of validating machine learning (ML) predictions in catalyst design with experimental data, a key advancement for accelerating drug discovery and development. It covers the foundational paradigm shift from trial-and-error methods to data-driven discovery, outlines core ML methodologies and their application in predicting catalytic activity and properties, and addresses central challenges like data quality and model interpretability. The piece provides a framework for the experimental verification of ML-guided catalysts, showcasing case studies with quantitative performance metrics. Finally, it synthesizes key takeaways and discusses future directions, including the role of regulatory science in fostering the adoption of these innovative approaches.

The New Paradigm: How Machine Learning is Transforming Catalyst Discovery

The development of new catalysts has long been a cornerstone of advances in chemical manufacturing, energy production, and pharmaceutical development. Traditionally, this process has relied heavily on empirical trial-and-error approaches guided by researcher intuition and prior knowledge—methods that are often time-consuming, resource-intensive, and limited by human cognitive biases [1] [2]. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is fundamentally transforming this paradigm, enabling a more systematic, data-driven approach to catalyst discovery and optimization.

This guide examines the evolution of catalysis research through three distinct stages empowered by ML: from data-driven prediction to generative design, and finally to experimental validation. We objectively compare the performance of different ML approaches and provide detailed methodologies for key experiments, highlighting how this integrated pipeline is accelerating the discovery of novel, high-performance catalysts.

Stage 1: Data-Driven Prediction and Optimization

The foundational stage in modern catalysis research involves using ML to extract meaningful patterns from existing experimental or computational data to predict catalytic performance and optimize reaction conditions.

Machine Learning Fundamentals in Catalysis

Machine learning applications in catalysis typically employ several key paradigms and algorithms [1]:

- Supervised Learning: Trains models on labeled datasets to map input features (e.g., molecular descriptors) to target properties (e.g., yield, enantioselectivity). Commonly used for classification and regression tasks.

- Unsupervised Learning: Identifies inherent patterns and groupings in unlabeled data, useful for clustering similar catalysts or reducing dimensionality of complex datasets.

- Key Algorithms: Frequently employed algorithms include Random Forest (an ensemble of decision trees), Linear Regression, and more complex deep learning models like Graph Neural Networks.

Table 1: Key Machine Learning Algorithms in Catalysis Research

| Algorithm | Learning Type | Typical Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | Supervised | Yield prediction, activity classification | Handles high-dimensional data, provides feature importance |

| Linear Regression | Supervised | Quantitative structure-activity relationships | Simple, interpretable, good baseline model |

| Graph Neural Networks | Supervised/Self-supervised | Predicting molecular properties, reaction outcomes | Naturally models molecular structure, high accuracy |

| Variational Autoencoders | Unsupervised/Generative | Novel catalyst design, latent space exploration | Enables inverse design, generates novel structures |

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

A representative example of this approach comes from research on asymmetric β-C(sp³)–H activation reactions, where researchers developed an ensemble prediction (EnP) model to predict enantioselectivity (%ee) [3]. The experimental workflow involved:

- Data Curation: Manually compiling a dataset of 220 experimentally reported reactions, each represented as concatenated SMILES strings of the catalyst precursor, chiral ligand, substrate, coupling partner, solvent, base, and reaction conditions.

- Model Training: Implementing a transfer learning approach where a chemical language model (CLM) was first pretrained on 1 million unlabeled molecules from the ChEMBL database, then fine-tuned on the reaction dataset.

- Ensemble Implementation: Creating 30 independently trained models (M1 to M30) on different random training set splits (70% of data each) to enhance prediction robustness on sparse, imbalanced data.

- Performance Validation: The EnP model demonstrated high reliability in predicting %ee for test set reactions, providing a robust foundation for guiding experimental efforts.

Stage 2: Generative Design of Novel Catalysts

Building on predictive models, the second stage employs generative AI to design novel catalyst structures beyond existing chemical libraries, moving from optimization to true discovery.

Generative Model Architectures

Recent advances have introduced several powerful frameworks for catalyst generation:

- CatDRX: A reaction-conditioned variational autoencoder (VAE) that generates catalysts and predicts performance based on reaction components (reactants, reagents, products, reaction time) [4]. The model is pretrained on diverse reactions from the Open Reaction Database (ORD) then fine-tuned for specific applications.

- Transfer Learning-Based Generators: Models pretrained on large molecular databases then fine-tuned on specific catalyst classes, such as the fine-tuned generator (FnG) for chiral amino acid ligands in C–H activation reactions [3].

- Conditional Generation: Approaches that incorporate reaction conditions as constraints during generation, enabling targeted exploration of catalyst space for specific transformations.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Generative Models in Catalyst Design

| Model/Approach | Architecture | Application Scope | Key Advantages | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CatDRX [4] | Reaction-conditioned VAE | Broad reaction classes | Conditions generation on full reaction context; competitive yield prediction (RMSE: 7.8-15.2 across datasets) | Case studies with knowledge filtering & computational validation |

| FnG Model [3] | Transfer learning (RNN) | Chiral ligands for C–H activation | Effective novel ligand generation from limited data (77 examples) | Prospective wet-lab validation with excellent agreement for most predictions |

| DEAL Framework [5] | Active learning + enhanced sampling | Reactive ML potentials for heterogeneous catalysis | Data-efficient (≈1000 DFT calculations/reaction); robust pathway sampling | Validated on NH₃ decomposition on FeCo; calculated free energy profiles |

Experimental Workflow for Generative Design

The standard workflow for generative catalyst design involves [3] [4]:

- Model Pretraining: Training on large, diverse reaction databases (e.g., Open Reaction Database, ChEMBL) to learn general chemical principles.

- Task-Specific Fine-Tuning: Adapting the pretrained model to specific catalytic transformations using smaller, curated datasets.

- Candidate Generation: Sampling novel catalyst structures from the model's latent space, often with optimization toward desired properties.

- Knowledge-Based Filtering: Applying chemical knowledge and synthesizability filters (e.g., SYBA score) to prioritize promising candidates.

- Computational Validation: Using DFT calculations or molecular dynamics to assess predicted performance before experimental testing.

Stage 3: Experimental Validation and Model Refinement

The critical final stage involves experimental testing of ML-generated catalysts, closing the loop between prediction and reality while providing essential feedback for model improvement.

Validation Methodologies Across Catalyst Types

Experimental validation approaches vary significantly between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalytic systems:

For Heterogeneous Catalysts [6]:

- Synthesis & Characterization: Predicted alloy catalysts (e.g., Pt₃Ru₁/₂Co₁/₂ for NH₃ electrooxidation) are synthesized as nanoparticles on supports like reduced graphene oxide. Characterization uses HAADF-STEM, XRD, XPS, and elemental mapping to confirm predicted structures.

- Electrochemical Testing: Performance evaluation through techniques like cyclic voltammetry under standardized conditions to measure mass activity and compare against baseline catalysts (e.g., Pt, Pt₃Ir).

- Stability Assessment: Long-term testing to verify catalyst stability under operational conditions, a crucial consideration for practical application.

For Homogeneous Catalysts [3]:

- Prospective Validation: ML-generated chiral ligands are synthesized and tested in target reactions (e.g., asymmetric β-C(sp³)–H functionalization).

- Performance Metrics: Precise measurement of yield and enantioselectivity (%ee) under controlled conditions, with comparison to ML predictions.

- Scope Evaluation: Testing successful catalysts across diverse substrates to assess generality and limitations.

Case Study: Prospective Validation of Generated Ligands

A comprehensive validation study on asymmetric β-C(sp³)–H activation demonstrated both the promise and challenges of ML-driven catalyst discovery [3]:

- Experimental Protocol: Researchers generated novel chiral amino acid ligands using a fine-tuned generator (FnG) model trained on only 77 known ligands. These were evaluated using the ensemble prediction (EnP) model for %ee, then synthesized and tested experimentally.

- Results: Most ML-generated reactions showed excellent agreement with EnP predictions, validating the overall approach.

- Critical Finding: The study emphasized that not all generated candidates performed well, highlighting the continued importance of domain expertise in selecting and refining ML suggestions before experimental investment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Guided Catalyst Discovery

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Salts | Catalyst precursors for heterogeneous and homogeneous systems | Pt, Pd, Ir, Cu, Fe, Co salts for alloy nanoparticles or molecular complexes [6] [3] |

| Chiral Ligand Libraries | Control enantioselectivity in asymmetric catalysis | Amino acid derivatives, phosphines, N-heterocyclic carbenes [3] |

| High-Throughput Screening Platforms | Rapid generation of consistent, large-scale datasets | Automated systems evaluating 20+ catalysts under 216+ conditions [7] |

| DFT Computational Resources | Generate training data and validate predictions | Calculate adsorption energies, transition states, reaction barriers [6] [5] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Tunable catalyst supports with defined structures | PCN-250(Fe₂M) for light alkane C–H activation [6] |

The evolution from trial-and-error experimentation through the three stages of ML-powered catalysis research represents a fundamental shift in approach. The most successful frameworks seamlessly integrate predictive modeling, generative design, and rigorous experimental validation into an iterative cycle where each stage informs and improves the others.

Current evidence demonstrates that ML approaches can significantly reduce experimental workload, enhance mechanistic understanding, and guide rational catalyst development [1]. However, challenges remain in data scarcity, model generalizability across reaction classes, and the need for closer integration between computational predictions and experimental execution. The future of catalyst discovery lies not in replacing human expertise with AI, but in developing synergistic workflows that leverage the strengths of both computational and experimental approaches to accelerate the development of more efficient, selective, and sustainable catalysts.

The integration of artificial intelligence into scientific research has catalyzed a paradigm shift from traditional trial-and-error approaches to data-driven discovery. Within this transformation, supervised, unsupervised, and hybrid learning represent distinct methodological frameworks for extracting knowledge from data. In fields such as catalyst prediction and drug development, where experimental validation is both crucial and resource-intensive, selecting the appropriate machine learning approach is critical for generating reliable, actionable insights. This guide objectively compares these core methodologies through their theoretical foundations, performance characteristics, and practical applications within scientific domains requiring experimental validation, providing researchers with a structured framework for methodological selection.

Core Conceptual Frameworks and Differences

The fundamental distinction between supervised and unsupervised learning lies in the use of labeled data. Supervised learning requires a dataset containing both input data and the corresponding correct output values, allowing the algorithm to learn the mapping function from inputs to outputs [8] [9]. In contrast, unsupervised learning identifies inherent structures, patterns, or relationships within unlabeled input data without any predefined output labels or human guidance [8] [10].

These fundamental differences inform their respective goals and applications. Supervised learning aims to predict outcomes for new, unseen data based on patterns learned from labeled examples, making it suitable for tasks like classification and regression [8] [11]. Unsupervised learning seeks to discover previously unknown patterns and insights, excelling at exploratory data analysis, clustering, and dimensionality reduction [10] [12]. The following table summarizes the key distinctions:

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Supervised and Unsupervised Learning

| Aspect | Supervised Learning | Unsupervised Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Data Requirements | Labeled input-output pairs [8] | Only unlabeled input data [8] |

| Primary Goals | Prediction, classification, regression [8] | Discovery of hidden patterns, clustering [10] |

| Model Output | Predictions for new data [8] | Insights into data structure [8] |

| Common Algorithms | Logistic Regression, Decision Trees, Neural Networks [11] | K-means, Hierarchical Clustering, PCA [10] [11] |

| Expert Intervention | Required for data labeling [8] | Required for interpreting results [8] |

The Hybrid Approach: Integrating Paradigms

Semi-supervised or hybrid learning leverages both labeled and unlabeled data, addressing limitations inherent in using either approach alone [8] [9]. This is particularly valuable in scientific domains where acquiring labeled data is expensive or time-consuming, but large volumes of unlabeled data are available. For instance, in medical imaging, a radiologist might label a small subset of CT scans, and a model can use this foundation to learn from a much larger set of unlabeled images, significantly improving accuracy without prohibitive labeling costs [8]. Hybrid models are gaining momentum in areas like oncology drug development, where they combine mechanistic pharmacometric models with data-driven machine learning to enhance prediction reliability [13].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The performance characteristics of supervised and unsupervised learning models differ significantly, influencing their suitability for specific scientific tasks. The following tables summarize quantitative performance data and key advantages and disadvantages.

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Catalytic Activity Prediction

| Model Type | Task | Performance Metrics | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning [14] | Predict catalytic performance (e.g., yield) | RMSE, MAE, R² | Achieves highly accurate and trustworthy results when trained on high-quality labeled data [15]. |

| Unsupervised Learning [14] | Cluster catalyst types or reaction conditions | Cluster purity, Silhouette score | Useful for initial data exploration and identifying natural groupings in catalyst data [10]. |

| Hybrid Model (CatDRX) [4] | Joint generative & predictive task for catalysts | RMSE, MAE | Demonstrates superior or competitive performance in yield prediction; performance drops on data far outside its pre-training domain [4]. |

Table 3: Advantages and Disadvantages at a Glance

| Approach | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning [15] [11] | 1. High accuracy and predictability with good data.2. Performance is straightforward to measure.3. Wide applicability to classification/regression tasks. | 1. High dependency on large, accurately labeled datasets.2. Prone to overfitting on noisy or small datasets.3. Time-consuming and expensive data labeling. |

| Unsupervised Learning [10] [11] | 1. No need for labeled data, saving resources.2. Can discover novel, unexpected patterns.3. Excellent for exploratory data analysis. | 1. Results can be unpredictable and harder to validate.2. Performance is challenging to quantify objectively.3. May be computationally intensive with large datasets. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for Supervised Learning in Catalysis

A typical workflow for developing a supervised model for catalytic property prediction involves several key stages [14]:

- Data Acquisition and Curation: Collect a high-quality dataset of catalysts with known target properties (e.g., reaction yield, enantioselectivity). Sources can include high-throughput experiments or computational databases like the Open Reaction Database (ORD) [4].

- Feature Engineering (Descriptor Extraction): Represent each catalyst using meaningful descriptors. These can be physical-chemical descriptors (e.g., adsorption energies, electronic properties) [14] or structural representations like molecular fingerprints (ECFP) [4] or graph-based features.

- Model Training and Validation: Split the labeled data into training and testing sets. Train a supervised algorithm (e.g., Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, or Neural Networks) on the training set. Performance is evaluated on the held-out test set using metrics like Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) [4].

- Experimental Validation: The model's predictions for new catalyst candidates are validated through controlled laboratory experiments or high-fidelity computational simulations like Density Functional Theory (DFT) [4].

Protocol for Unsupervised Learning in Catalyst Discovery

Unsupervised learning is often applied in the early stages of discovery to profile and understand the chemical space [14]:

- Data Collection: Assemble a diverse library of catalytic materials or molecular structures, which may be unlabeled.

- Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering: Apply techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the feature space and visualize the data. Then, use clustering algorithms (e.g., K-means, Hierarchical Clustering) to group catalysts based on inherent similarities in their descriptors [10] [12].

- Cluster Analysis and Interpretation: Researchers manually analyze the formed clusters to identify common structural or property motifs within each group. This can reveal novel catalyst families or design principles [8].

- Hypothesis Generation and Downstream Validation: The insights from clustering generate hypotheses about promising catalyst candidates, which are then tested and validated through supervised modeling or direct experimentation.

Workflow of a Hybrid Model (CatDRX)

The CatDRX framework exemplifies a modern hybrid approach, integrating both generative and predictive tasks [4]. The diagram below illustrates its core workflow.

CatDRX Hybrid Model Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The experimental application of these ML models relies on a suite of computational and data resources. The following table details key components of the modern computational researcher's toolkit.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for ML in Catalysis and Drug Discovery

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Role in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Databases | Open Reaction Database (ORD) [4] | Provides large, diverse datasets of chemical reactions for pre-training machine learning models, improving their generalizability. |

| Feature Extraction Tools | Reaction Fingerprints (RXNFP) [4], Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP) [4] | Converts molecular and reaction structures into numerical vectors that machine learning algorithms can process. |

| Validation & Simulation Software | Density Functional Theory (DFT) [4] | Provides high-fidelity computational validation of catalyst properties and reaction mechanisms predicted by ML models. |

| Core Machine Learning Algorithms | K-means Clustering [10], Decision Trees [11], Random Forest [14], Variational Autoencoders (VAE) [4] | The core computational engines for performing clustering, classification, regression, and generative tasks. |

| Hybrid Modeling Frameworks | hPMxML (Hybrid Pharmacometric-ML) [13], Context-Aware Hybrid Models [16] | Combines mechanistic/physical models with data-driven ML to enhance reliability and interpretability in domains like drug development. |

Supervised, unsupervised, and hybrid learning each occupy a distinct and valuable niche in the scientific toolkit. Supervised learning provides high-precision predictive models when comprehensive labeled data is available, while unsupervised learning offers powerful capabilities for exploratory analysis and pattern discovery in raw data. The emerging paradigm of hybrid learning, which strategically combines both approaches, is particularly promising for complex scientific domains like catalyst prediction and drug discovery. It leverages small amounts of expensive labeled data alongside vast, inexpensive unlabeled data, creating models that are both data-efficient and powerful. As the field progresses, addressing challenges related to data quality, model interpretability, and robust validation will be key to further integrating these machine learning concepts into the iterative cycle of scientific prediction and experimental validation [14] [13].

The integration of machine learning (ML) into catalyst discovery has fundamentally reshaped traditional research paradigms, offering a low-cost, high-throughput path to uncovering complex structure-performance relationships [14]. However, the performance of ML models is highly dependent on data quality and volume, and their predictions often remain just that—predictions—until confirmed through rigorous experimental validation [14] [17]. This article demonstrates why experimental verification is a non-negotiable final step in the computational workflow, serving as the critical bridge between theoretical potential and practical application. Without this step, even the most sophisticated algorithms risk generating results that are computationally elegant but practically irrelevant. The following sections provide a comparative analysis of ML-driven catalytic research, detail essential experimental protocols, and present a structured framework for validating computational predictions, offering researchers a roadmap for integrating robust validation into their discovery pipelines.

Comparative Analysis: Machine Learning Predictions vs. Experimental Reality

Performance Benchmarking of ML Approaches

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of ML Model Performance in Catalysis

| Study Focus | ML Model Type | Reported Performance Metric | Key Experimental Validation Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enantioselective C–H Bond Activation [18] | Ensemble Prediction (EnP) Model with Transfer Learning | Highly reliable predictions on test set | Prospective wet-lab validation showed excellent agreement for most ML-generated reactions |

| CO₂ to Methanol Conversion [17] | Pre-trained Equiformer_V2 MLFF | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 0.16 eV for adsorption energies on benchmarked materials (Pt, Zn, NiZn) | Outliers and noticeable scatter for specific materials (e.g., Zn) highlighted need for validation |

| General Catalyst Screening [14] | Various Supervised Learning & Symbolic Regression | Performance dependent on data quality & feature engineering | Identified data acquisition and standardization as major challenges for real-world application |

Case Studies in Prospective Validation

Ligand Design for C–H Activation: A molecular machine learning approach for enantioselective β-C(sp³)–H activation employed a transfer learning strategy. An ensemble of 30 fine-tuned chemical language models (CLMs) was created to predict enantiomeric excess (%ee). The model was trained on 220 known reactions and then used to predict outcomes for novel, ML-generated ligands. Subsequent wet-lab experiments confirmed that most of these proposed reactions exhibited excellent agreement with the EnP predictions, providing a compelling proof-of-concept for a closed-loop ML-experimental workflow [18].

Descriptor Development for CO₂ Conversion: In a study aimed at discovering catalysts for CO₂ to methanol conversion, a new descriptor—the Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED)—was developed. The underlying machine-learned force fields (MLFFs) were first benchmarked against traditional Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations. While the overall MAE was an impressive 0.16 eV, the performance was not uniform; predictions for Pt were precise, but results for Zn showed significant scatter. This material-dependent variation in accuracy necessitated a robust validation protocol to affirm the reliability of the predicted AEDs across the entire dataset of nearly 160 materials before any conclusions could be drawn [17].

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Validation

Workflow for Validating ML-Derived Catalysts

The following diagram illustrates a robust, generalized workflow for the experimental validation of ML-predicted catalysts, integrating steps from successful case studies.

Detailed Methodological Steps

Computational Candidate Selection & Model Benchmarking:

- Novel Candidate Generation: Use generative models (e.g., fine-tuned language models on known chiral ligands) to propose new molecular structures. Filter generated candidates based on practical chemical constraints (e.g., presence of a chiral center, key functional groups) [18].

- Model & Descriptor Validation: Before experimental synthesis, benchmark the computational method's accuracy. For MLFFs, this involves calculating adsorption energies for a subset of materials with known DFT values to establish a mean absolute error (MAE), as demonstrated with Pt, Zn, and NiZn [17].

Wet-Lab Synthesis & Catalytic Testing:

- Reaction Setup: Assemble reactions using the ML-proposed components (catalyst precursor, generated ligand, substrate, coupling partner, solvent, base) under specified conditions (e.g., temperature, atmosphere) [18].

- Performance Measurement: For catalytic reactions, key metrics include:

- Enantiomeric Excess (%ee): Determined using chiral chromatography or other analytical techniques to quantify stereoselectivity [18].

- Conversion and Yield: Quantified using methods like gas chromatography (GC) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [17].

- Adsorption Energy Validation: For descriptor-based studies, compare the computationally derived AEDs with experimental catalytic activity and selectivity data to establish a correlation [17].

Data Analysis & Model Refinement:

- Quantitative Comparison: Compare experimental results directly with ML predictions using pre-defined metrics (e.g., accuracy of %ee prediction, correlation with adsorption energy).

- Iterative Feedback: Discrepancies between prediction and experiment are not failures but valuable data points. These results should be fed back into the ML model to retrain and improve its accuracy and generalizability for future discovery cycles [18] [17].

Visualization of the Benchmarking and Validation Logic

A robust validation strategy requires more than a single workflow; it needs a structured framework for comparing methods and interpreting results. The following diagram outlines the critical decision points in a benchmarking study, from purpose definition to final recommendation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Catalytic Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Validation |

|---|---|

| Chiral Amino Acid Ligands | Key components for asymmetric induction in enantioselective catalysis (e.g., C–H activation). Both known and ML-generated variants are tested [18]. |

| Aryl Halide Coupling Partners | Electrophilic reaction components in cross-coupling reactions (e.g., p-iodotoluene). Diversity is crucial for testing reaction scope [18]. |

| Catalyst Precursors | Metal salts or complexes (e.g., Pd, Ir, Rh) that generate the active catalytic species in situ [18] [17]. |

| Metallic Alloy Catalysts | Heterogeneous catalysts (e.g., ZnRh, ZnPt₃) screened for reactions like CO₂ hydrogenation to methanol. Surfaces with multiple facets are critical [17]. |

| Key Reaction Intermediates | Molecules like *H, *OH, *OCHO (formate), and *OCH₃ (methoxy). Their adsorption energies on catalyst surfaces are used to calculate activity descriptors like AEDs [17]. |

| Stable Base Additives | Used to deprotonate substrates and facilitate critical steps in catalytic cycles, such as C–H deprotonation [18]. |

The journey from a computational prediction to a validated scientific discovery is complex and non-linear. As demonstrated, even models with high overall accuracy can produce outliers or exhibit material-specific weaknesses [17]. Therefore, experimental verification is not a mere formality but the cornerstone of credible and reliable research in machine learning for catalysis. It grounds digital insights in physical reality, confirms the practical utility of novel discoveries like ML-generated ligands [18], and, most importantly, provides the high-quality data necessary to refine the next generation of models. By adhering to rigorous benchmarking principles [19] and integrating robust validation protocols into their core workflows, researchers can ensure that the promise of data-driven catalyst discovery is fully realized.

ML in Action: Predictive Models and Generative Design for Catalysts

The integration of machine learning (ML) into catalysis research represents a paradigm shift, moving beyond traditional trial-and-error approaches to a data-driven methodology that accelerates catalyst discovery and optimization. Catalysis informatics employs advanced algorithms to decipher complex relationships between catalyst composition, structure, reaction conditions, and catalytic performance. This guide provides an objective comparison of four pivotal ML algorithms—Random Forest, Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), XGBoost, and Linear Regression—within the critical context of experimental validation. As research demonstrates, the ultimate value of these computational models lies in their ability to not just predict but to guide and be confirmed by tangible laboratory results, creating a virtuous cycle of computational prediction and experimental verification [20] [21].

The unique challenge in catalytic applications lies in the multi-faceted nature of catalyst performance, which often encompasses yield, selectivity, conversion, and stability under specific reaction conditions. Machine learning algorithms must navigate high-dimensional parameter spaces including metal composition, support materials, synthesis conditions, and operational variables like temperature and pressure. This complexity necessitates algorithms capable of handling non-linear relationships and complex interactions while providing insights that researchers can leverage for rational catalyst design. The validation of these models through experimental synthesis and testing remains the gold standard for establishing their predictive power and utility in real-world applications [20] [22].

Algorithm Comparison: Performance Metrics and Catalytic Applications

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Algorithms in Catalysis Research

| Algorithm | Key Strengths | Limitations | Validated Catalytic Applications | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | Handles high-dimensional data; Robust to outliers; Provides feature importance | Limited extrapolation capability; Black-box nature | Reduction of nitrophenols and azo dyes [23]; Lung surfactant inhibition prediction [24] | Best performance for TNP, MB, RHB reduction (RF) [23]; 96% accuracy in surfactant inhibition (MLP superior) [24] |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) | Excellent non-linear modeling; Pattern recognition in complex data | Large data requirements; Computationally intensive | VOC oxidation over bimetallic catalysts [20]; Kinetic modeling of n-octane hydroisomerization [25] | Accurate prediction of toluene (96%) and cyclohexane (91%) conversion [20]; Proper kinetics modeling as alternative to mechanistic models [25] |

| XGBoost | High predictive accuracy; Handles missing data; Computational efficiency | Parameter sensitivity; Potential overfitting without proper regularization | HDAC1 inhibitor prediction [26]; QSAR modeling [27]; Nitrophenol reduction prediction [23] | Best performance with NP and DNP reduction [23]; Strong QSAR performance vs. LightGBM and CatBoost [27]; R²=0.88 for HDAC1 inhibition [26] |

| Linear Regression | Interpretability; Computational efficiency; Mechanistic insight | Limited to linear relationships; Cannot capture complex interactions | Asymmetric reaction optimization [22]; Steric parameter analysis in catalysis [22] | Multivariate linear regression relates steric parameters to enantioselectivity [22] |

Table 2: Data Requirements and Implementation Considerations

| Algorithm | Data Volume Requirements | Feature Preprocessing Needs | Hyperparameter Tuning Complexity | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | Medium to Large | Low (handles mixed data types) | Low to Medium | Medium (feature importance available) |

| ANN | Large (avoids overfitting) | High (normalization critical) | High (multiple architecture choices) | Low (black-box nature) |

| XGBoost | Medium to Large | Low (handles missing values) | Medium to High | Medium (feature importance available) |

| Linear Regression | Small to Medium | Medium (collinearity concern) | Low | High (transparent coefficients) |

Experimental Validation: Case Studies and Methodologies

ANN-GA Hybrid Modeling for VOC Oxidation

Experimental Objective: To develop and validate a hybrid artificial neural network-genetic algorithm (ANN-GA) model for predicting optimal bimetallic catalysts for simultaneous deep oxidation of toluene and cyclohexane [20].

Catalyst Synthesis and Testing:

- Catalyst Preparation: Bimetallic catalysts (alloy and core-shell structures) were supported on almond shell-based activated carbon via heterogeneous deposition-precipitation (HDP). Metals (copper and cobalt) were dispersed with different ratios (Cu/Co: 1:1, 1:3, 3:1) at 8 wt% total metal loading [20].

- Reaction Testing: Catalytic oxidation performed in a tubular fixed-bed reactor with VOC concentrations ranging from 1000-8000 ppmv at temperatures of 150-350°C. Products were analyzed using GC-MS with a 30m HP-5MS column [20].

- Performance Metrics: Conversion efficiency calculated using the formula: Removal Efficiency (%) = [(Ci - Ce)/Ci] × 100, where Ci and C_e are inlet and exit VOC concentrations respectively [20].

Characterization Techniques:

- Surface Area Analysis: BET and BJH methods using N₂ adsorption/desorption at 77K [20].

- Structural Properties: XRD analysis with Cu Kα radiation at scanning rate of 3° min⁻¹ [20].

- Morphology: TEM and FESEM at 100 keV and 15 kV respectively [20].

- Composition: Inductively coupled plasma (ICP) analysis for exact metal content determination [20].

Model Validation Results: The optimal catalyst predicted by the ANN-GA model contained 2.5 wt% copper oxide and 5.5 wt% cobalt oxide over activated carbon. Experimental validation confirmed 96% toluene conversion (model predicted 95.50%) and 91% cyclohexane conversion (model predicted 91.88%), demonstrating remarkable predictive accuracy [20].

XGBoost for Environmental Catalysis and Inhibitor Prediction

Water Purification Catalyst Study:

- Objective: Predict catalytic reduction performance of PdO-NiO for environmental pollutants including nitrophenols and azo dyes [23].

- Methodology: Multiple ML algorithms (Linear Regression, SVM, GBM, RF, XGBoost) were evaluated for predicting catalytic activity against various contaminants including 4-nitrophenol, 2,4-dinitrophenol, and methylene blue [23].

- Performance Metrics: Model performance assessed using Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) [23].

- Results: XGBoost demonstrated best performance for nitrophenol (NP) and dinitrophenol (DNP) reduction prediction, while Random Forest excelled for trinitrophenol (TNP), methylene blue, and Rhodamine B [23].

HDAC1 Inhibitor Research:

- Objective: Develop predictive QSAR models for histone deacetylase 1 inhibitors using GA-XGBoost approach [26].

- Methodology: Combined genetic algorithm feature selection with XGBoost modeling on diverse heterocycle datasets, with validation using SHAP analysis for interpretability [26].

- Performance Metrics: Training performance showed R² value of 0.8797, explaining 87.97% of variance in training data, with strong cross-validation and external validation results [26].

Linear Regression for Mechanistic Analysis in Asymmetric Catalysis

Experimental Objective: Utilize multivariate linear regression (MLR) models with physically meaningful molecular descriptors for reaction optimization and mechanistic interrogation [22].

Methodology:

- Descriptor Selection: Employed steric parameters (Sterimol values, Tolman cone angle, percent buried volume) and electronic parameters derived from computational chemistry and experimental measurements [22].

- Model Development: Correlated molecular descriptors with reaction outcomes including enantioselectivity, turnover number, and yield [22].

- Validation Approach: Compared predicted versus experimental outcomes across diverse catalyst structures, with emphasis on mechanistic interpretability [22].

Key Applications: Successfully applied to asymmetric catalysis including desymmetrization of bisphenols, Nozaki–Hiyama–Kishi propargylation, and nickel-catalyzed Suzuki C-sp³ coupling, demonstrating the ability to extract meaningful structure-function relationships from limited datasets [22].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Catalysis ML Validation

Table 3: Key Experimental Reagents and Characterization Techniques

| Reagent/Technique | Function in Experimental Validation | Specific Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Activated Carbon Support | High-surface-area support for dispersing active metal sites | Almond shell-based AC for bimetallic Cu-Co catalysts [20] |

| Bimetallic Precursors | Source of active catalytic sites | Cobalt and copper nitrate solutions for HDP synthesis [20] |

| Fixed-Bed Reactor System | Controlled environment for catalytic testing | VOC oxidation at 150-350°C with variable concentration [20] |

| GC-MS Analysis | Quantitative and qualitative analysis of reaction products | Agilent system with 5975C mass detector for VOC conversion [20] |

| BET/BJH Analysis | Surface area and pore structure characterization | N₂ adsorption at 77K for textural properties [20] |

| XRD | Crystalline structure and phase identification | STOE instrument with Cu Kα radiation for catalyst structure [20] |

| TEM/FESEM | Morphology and particle size distribution | EM208-Philips and Hitachi S-4160 instruments [20] |

| ICP-OES | Precise elemental composition analysis | PerkinElmer Optima 8000 for metal loading verification [20] |

Workflow Diagram: Integrating Machine Learning with Experimental Catalysis Research

Machine Learning-Experimental Workflow Integration

The diagram illustrates the critical integration between computational prediction and experimental validation in modern catalysis research. The process begins with dataset creation from historical experimental data, typically containing 50+ data points encompassing catalyst compositions, synthesis parameters, and performance metrics [20]. This data fuels model training using algorithms such as ANN, XGBoost, Random Forest, or Linear Regression, each selected based on dataset size and complexity. Optimization techniques like Genetic Algorithms then identify promising catalyst formulations by navigating the multi-dimensional parameter space [20] [26].

The predicted optimal catalysts proceed to experimental validation through carefully controlled synthesis protocols such as heterogeneous deposition-precipitation [20]. Performance testing under realistic conditions (e.g., fixed-bed reactors for VOC oxidation) generates crucial validation data, while advanced characterization techniques (BET, XRD, TEM, ICP) provide structural insights correlating with performance [20]. The final validation phase compares predicted versus experimental results, creating a feedback loop for model refinement that enhances predictive accuracy for future iterations, ultimately yielding validated models that significantly accelerate catalyst development cycles.

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that algorithm selection in catalysis research depends critically on specific research objectives, data resources, and validation requirements. Artificial Neural Networks excel in modeling complex non-linear relationships in catalysis, particularly when hybridized with optimization algorithms like Genetic Algorithms, as evidenced by their successful prediction of bimetallic catalyst performance for VOC oxidation [20]. XGBoost provides robust performance for QSAR modeling and virtual screening applications, offering an optimal balance between predictive accuracy, computational efficiency, and feature importance interpretability [26] [27]. Random Forest serves as a versatile tool for various classification and regression tasks in catalysis, particularly when dealing with diverse data types and requiring inherent feature selection [23] [24]. Linear Regression remains valuable for mechanistically interpretable modeling, especially when leveraging physically meaningful molecular descriptors in multivariate analysis [22].

The critical consensus across studies emphasizes that algorithmic predictions must undergo rigorous experimental validation to establish true predictive power. This validation requires comprehensive catalyst characterization and performance testing under relevant conditions. As the field advances, the integration of these algorithms into hybrid approaches—combining the strengths of multiple methods—represents the most promising path toward accelerating catalyst discovery and optimization while deepening our fundamental understanding of catalytic processes.

The discovery and development of catalysts and therapeutic compounds have long been constrained by traditional trial-and-error methodologies, which are notoriously time-consuming and resource-intensive. The emergence of generative artificial intelligence (AI) represents a paradigm shift from purely predictive models to systems capable of inverse design, where desired properties guide the creation of novel molecular structures. Framed within the broader thesis of validating machine learning predictions with experimental data, this guide objectively compares the performance of cutting-edge generative frameworks, including the recently developed CatDRX (Catalyst Discovery based on a ReaXion-conditioned variational autoencoder). Unlike conventional models limited to specific reaction classes, CatDRX introduces a reaction-conditioned approach that generates potential catalysts and predicts their performance by learning from broad reaction databases, thus enabling a more comprehensive exploration of the chemical space for researchers and drug development professionals [4].

Comparative Analysis of Key Generative AI Frameworks

The landscape of generative AI for scientific discovery includes several distinct architectural approaches. The table below provides a high-level comparison of three prominent frameworks.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Generative AI Frameworks in Molecular Design

| Framework | Core Architecture | Primary Application | Key Innovation | Model Conditioning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CatDRX [4] | Reaction-Conditioned Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | Catalyst Design & Optimization | Integrates reaction components (reactants, reagents) for catalyst generation | Reaction conditions (reactants, products, reagents, time) |

| VGAN-DTI [28] | Hybrid VAE + Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) | Drug-Target Interaction (DTI) Prediction | Combines VAE's feature encoding with GAN's generative diversity | Drug and target protein features |

| MMGX [29] | Multiple Molecular Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Property & Activity Prediction | Leverages multiple molecular graph representations for improved interpretation | Atom, Pharmacophore, JunctionTree, and FunctionalGroup graphs |

Experimental Performance and Quantitative Benchmarking

A critical measure of a model's utility is its performance on benchmark tasks. The following table summarizes the published quantitative results for the featured frameworks, providing a basis for objective comparison. CatDRX's performance is noted in yield prediction, whereas VGAN-DTI excels in binding affinity classification.

Table 2: Summary of Experimental Performance Metrics

| Framework | Dataset(s) | Key Performance Metrics | Reported Performance | Comparative Baselines |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CatDRX [4] | Multiple downstream reaction datasets (e.g., BH, SM, UM, AH) | Yield & Catalytic Activity Prediction (RMSE, MAE) | Competitive or superior performance in yield prediction; challenges with datasets outside pre-training domain (e.g., CC, PS) | Compared against reproduced existing models from original publications |

| VGAN-DTI [28] | BindingDB | Drug-Target Interaction Prediction (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1) | 96% Accuracy, 95% Precision, 94% Recall, 94% F1 Score | Outperformed existing DTI prediction methods |

| MMGX [29] | MoleculeNet benchmarks, pharmaceutical endpoint tasks, synthetic binding logics | Property Prediction Accuracy, Interpretation Fidelity | Relatively improved model performance, varying by dataset; provided comprehensive features consistent with background knowledge | Validated against ground truths in synthetic datasets |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

CatDRX Model Training and Validation [4]:

- Pre-training: The model is first pre-trained on a diverse set of reactions from the Open Reaction Database (ORD) to learn general representations of catalysts and their associated reaction components.

- Fine-tuning: The pre-trained model, including its encoder, decoder, and predictor modules, is subsequently fine-tuned on specific, smaller downstream datasets relevant to the target catalytic reactions.

- Conditional Generation: For inverse design, a latent vector is sampled and concatenated with an embedded condition vector (derived from reactants, reagents, products, and reaction time). This combined vector guides the decoder to generate novel catalyst structures.

- Validation: Generated catalyst candidates undergo optimization towards desired properties and are validated using computational chemistry tools and background chemical knowledge, as demonstrated in case studies.

VGAN-DTI Model Training [28]:

- Feature Encoding: A VAE encodes molecular structures (e.g., from SMILES strings) into a latent distribution, learning compressed representations. The loss function combines reconstruction loss and Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence.

- Adversarial Generation: A GAN's generator creates new molecular structures from random noise, while a discriminator network learns to distinguish between real and generated molecules. The two networks are trained adversarially.

- Interaction Prediction: A Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) takes the generated molecular features and target protein information as input to predict binding affinities and classify drug-target interactions.

MMGX Model Workflow [29]:

- Multi-Representation Encoding: A single molecule is simultaneously converted into multiple graph representations: Atom graph, Pharmacophore graph, JunctionTree, and FunctionalGroup graph.

- Graph Neural Network Processing: Each graph is processed by a Graph Neural Network (GNN) to learn representation-specific embeddings.

- Feature Fusion: The embeddings from the different graphs are combined (e.g., through concatenation) to form a unified molecular representation.

- Prediction and Interpretation: The fused representation is used for property prediction. An integrated attention mechanism provides interpretations from the perspective of each graph representation, offering diverse and chemically intuitive insights.

Workflow and Architectural Visualizations

CatDRX Reaction-Conditioned Generative Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core architecture and process of the CatDRX model for inverse catalyst design.

Diagram 1: CatDRX's reaction-conditioned VAE architecture integrates catalyst and reaction context to generate novel catalysts and predict their performance [4].

Generalized Inverse Design Workflow

This diagram outlines a universal validation-centric workflow for generative AI in molecular design, applicable across different frameworks.

Diagram 2: An iterative workflow for generative molecular design, emphasizing experimental validation as a core component for model refinement and hypothesis testing [4] [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation and validation of generative models like CatDRX rely on a suite of computational and experimental resources.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Generative AI-Driven Discovery

| Category | Item / Resource | Brief Function Description | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Databases | Open Reaction Database (ORD) | Provides a broad set of reaction data for pre-training generalist generative models. | [4] |

| BindingDB | Curated database of measured binding affinities, essential for training and validating Drug-Target Interaction models. | [28] | |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Provides predicted protein structures, enabling structure-based drug and catalyst design. | [31] [32] | |

| Software & Tools | Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Computational method for modeling electronic structures, used for validating generated catalysts and calculating properties. | [4] [30] |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Libraries | Software frameworks for building and training models on graph-structured data like molecules. | [29] | |

| Rosetta (REvoLd) | Software suite for protein-ligand docking and design, useful for virtual screening. | [32] | |

| Molecular Representations | SMILES Strings | Text-based representation of molecular structure, commonly used as input for language-based models. | [4] [28] |

| Multiple Molecular Graphs (MMGX) | Alternative graph representations (e.g., Pharmacophore, Functional Group) that provide higher-level chemical insights for model learning and interpretation. | [29] | |

| Validation Assays | High-Throughput Screening (HTS) | Experimental method for rapidly testing the activity of thousands of candidate compounds. | [33] [28] |

| Enantioselectivity Measurement | Determines the stereoselectivity of a catalyst, a key performance metric in asymmetric synthesis. | [4] |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that generative AI models like CatDRX, VGAN-DTI, and MMGX are pushing the boundaries of inverse design in catalysis and drug discovery. Each framework offers distinct strengths: CatDRX through its reaction-conditioned generation for catalysts, VGAN-DTI with its high-precision interaction prediction, and MMGX via its interpretable, multi-perspective molecular representations. The critical differentiator for their successful application in real-world research and development lies in the rigorous validation loop that integrates in-silico predictions with experimental data. This process not only confirms the efficacy of generated molecules but also continuously refines the AI models, creating a virtuous cycle of discovery that accelerates the development of effective catalysts and therapeutics.

In the quest to develop more efficient, selective, and stable catalysts, researchers are increasingly turning to data-driven approaches. Descriptor engineering sits at the heart of this endeavor, creating quantifiable links between a catalyst's intrinsic molecular features and its macroscopic performance. The core principle involves identifying key physicochemical properties—descriptors—that can reliably predict catalytic activity, selectivity, and stability [34]. This paradigm is particularly powerful when combined with machine learning (ML), enabling the screening of vast material spaces in silico before committing resources to laboratory synthesis and testing [17]. The ultimate validation of this approach, however, rests on a closed loop of computation and experiment, where ML predictions guide experimental efforts, and experimental results, in turn, refine the computational models [18].

This guide objectively compares three dominant descriptor classes used in modern catalyst discovery: well-established theoretical descriptors, the emerging concept of Adsorption Energy Distributions (AEDs), and purely data-driven machine learning descriptors. We will dissect their underlying principles, present comparative performance data, and provide detailed experimental protocols for their validation, all framed within the critical context of bridging computational prediction with experimental reality.

Comparative Analysis of Descriptor Engineering Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Key Descriptor Engineering Approaches in Catalysis.

| Descriptor Approach | Fundamental Principle | Typical Input Features | Primary Performance Predictions | Experimental Validation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Descriptors (e.g., d-band center, OHP) | Links electronic structure to adsorption energetics based on quantum chemistry [34]. | d-band center, valence electron count, electronegativity, coordination number. | Intrinsic activity (overpotential, TOF), thermodynamic stability [34]. | Moderate (requires synthesis of predicted compositions and standard electrochemical testing). |

| Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED) | Characterizes the spectrum of adsorption energies across diverse surface facets and sites of a catalyst nanoparticle [17]. | Adsorption energies of key intermediates (*H, *OH, *OCHO, *OCH3) on multiple surface facets. | Overall catalytic activity, selectivity, and potential stability under operating conditions [17]. | High (requires synthesis of specific nanostructures and advanced characterization to confirm active sites). |

| Data-Driven ML Descriptors | Learns complex, non-linear relationships between a holistic representation of the catalyst and its performance from data [18]. | Learned representations from SMILES strings, graph-based molecular structures, or compositional fingerprints. | Enantioselectivity (%ee), reaction yield, multi-objective optimization [18]. | Variable (can be high for novel chemical spaces; requires synthesis and performance testing of proposed candidates). |

The choice of descriptor directly dictates the strategy for experimental validation. Theoretical descriptors like the d-band center provide a foundational understanding of electronic effects on activity, making them suitable for initial screening of catalyst compositions [34]. In contrast, the AED approach acknowledges the real-world complexity of catalysts, which present a multitude of surface facets and sites. This method has been applied to screen nearly 160 metallic alloys for CO₂ to methanol conversion, proposing new candidates like ZnRh and ZnPt₃ by comparing their AEDs to those of known effective catalysts [17]. Meanwhile, data-driven ML descriptors excel in navigating complex reaction landscapes, such as asymmetric synthesis, where they can predict nuanced outcomes like enantiomeric excess (%ee) by learning from a small dataset of ~220 reactions [18].

Table 2: Performance Summary of Descriptor-Engineered Catalysts from Case Studies.

| Catalyst System | Reaction | Descriptor Used | Key Performance Metric | Experimental Validation Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-based Catalysts (e.g., oxides, phosphides) [34] | Oxygen Evolution Reaction (OER) | d-band center, electronic configuration | Overpotential, stability | Guides design of vacancy engineering & doping strategies; performance confirmed via electrochemical testing. |

| ZnRh, ZnPt₃ (ML-proposed) [17] | CO₂ to Methanol Conversion | Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED) | Methanol yield, catalyst stability | Proposed as promising candidates; validation requires future synthesis and testing. |

| Ligand-Substrate Pairs (ML-generated) [18] | Enantioselective β-C(sp³)–H Activation | Learned representation from SMILES strings | Enantiomeric excess (%ee) | Wet-lab validation showed excellent agreement with predictions for most proposed reactions. |

Experimental Protocols for Validating Descriptor-Based Predictions

Validation of Thermocatalytic Performance (AED Approach)

The following protocol is adapted from high-throughput workflows for validating catalysts for CO₂ to methanol conversion, a critical reaction for closing the carbon cycle [17].

- Step 1: Catalyst Synthesis via Incipient Wetness Impregnation. The predicted catalyst compositions (e.g., bimetallic alloys like ZnRh) are synthesized. For a supported catalyst, an aqueous solution containing stoichiometric amounts of the precursor metal salts (e.g., RhCl₃·xH₂O and Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) is added to a porous support material, typically γ-Al₂O₃, until the point of incipient wetness. The material is subsequently dried at 120°C for 12 hours and then calcined in air at 400°C for 4 hours to decompose the salts into their respective oxides.

- Step 2: Reduction and Activation. The calcined catalyst is reduced in a flow of H₂ (e.g., 50 mL/min) at a specified temperature (e.g., 400°C) for 2-4 hours to form the active metallic phase. The temperature and duration are optimized based on the specific metals used.

- Step 3: Catalytic Performance Testing. The reduced catalyst is tested in a high-pressure fixed-bed reactor system. A typical reaction gas mixture (CO₂:H₂:N₂ = 3:9:1) is fed into the reactor at a defined pressure (e.g., 30-50 bar) and temperature (e.g., 220-260°C). The weight hourly space velocity (WHSV) is carefully controlled.

- Step 4: Product Analysis and Data Collection. The reactor effluent is analyzed using an online gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) and a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). Key performance metrics are calculated:

- CO₂ Conversion (%) = [(CO₂in - CO₂out) / CO₂_in] × 100

- Methanol Selectivity (%) = [Carbon in methanol products / Total carbon in all products] × 100

- Methanol Yield (%) = (CO₂ Conversion × Methanol Selectivity) / 100

- Step 5: Stability Assessment. The catalyst is subjected to a long-duration run (e.g., 100 hours) under reaction conditions to monitor changes in conversion and selectivity over time, providing critical data for stability predictions made by descriptors.

Validation of Enantioselective Performance (Data-Driven ML Approach)

This protocol is designed for validating ML predictions of enantioselectivity in catalytic C–H activation reactions, which is crucial for pharmaceutical synthesis [18].

- Step 1: Reaction Setup with ML-Proposed Conditions. In an inert atmosphere glovebox, a Schlenk tube or a sealed microwave vial is charged with the substrate (e.g., 0.2 mmol), the ML-proposed chiral ligand (e.g., 10 mol%), catalyst precursor (e.g., Pd(OAc)₂, 5 mol%), base (e.g., Cs₂CO₃, 2.0 equiv), and solvent (e.g., 2.0 mL of 1,2-dichloroethane).

- Step 2: Catalytic Reaction Execution. The reaction vessel is sealed, removed from the glovebox, and heated with vigorous stirring to the specified temperature (e.g., 100°C) for a set time (e.g., 24 hours). The reaction is monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) or liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS).

- Step 3: Work-up and Product Isolation. After cooling to room temperature, the reaction mixture is diluted with a suitable solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate) and washed with water and brine. The organic layer is separated, dried over anhydrous MgSO₄, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure.

- Step 4: Determination of Enantiomeric Excess. The crude product is purified by flash column chromatography. The enantiomeric excess (%ee) is determined by chiral high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) or supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC). The sample is injected onto a chiral stationary phase column, and the enantiomers are separated. The %ee is calculated as:

- %ee = |[Major Enantiomer] - [Minor Enantiomer]| / ([Major Enantiomer] + [Minor Enantiomer]) × 100

- Step 5: Data Correlation. The experimentally measured %ee is directly compared to the value predicted by the ML model (e.g., the Ensemble Prediction or EnP model) to validate the accuracy of the descriptor-based prediction [18].

Workflow Visualization of Descriptor Engineering and Validation

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational-experimental workflow for descriptor-driven catalyst discovery, from initial design to experimental validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental validation of descriptor-engineered catalysts relies on a suite of specialized reagents, instruments, and computational tools.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Catalyst Validation.

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Precursors | Metal salts (e.g., RhCl₃, Zn(NO₃)₂, Pd(OAc)₂), Ligands (e.g., chiral amino acids) | The building blocks for synthesizing the active catalyst phase as predicted by the model [18] [17]. |

| Support Materials | γ-Alumina (γ-Al₂O₃), Carbon black, Silica (SiO₂) | High-surface-area materials used to disperse and stabilize active metal nanoparticles [17]. |

| Reaction Gases | CO₂ (high purity), H₂ (high purity), N₂ (carrier gas) | Feedstock and reactant gases for catalytic testing in reactions like CO₂ hydrogenation [17]. |

| Analytical Instruments | Gas Chromatograph (GC), High-Performance Liquid Chromatograph (HPLC), Chiral HPLC/SFC | Used for quantitative and qualitative analysis of reaction products, yield, and selectivity, including enantiomeric excess [18] [17]. |

| Reaction Systems | High-pressure Fixed-Bed Reactor, Schlenk line, Microwave reactor | Enable the execution of catalytic reactions under controlled conditions of temperature, pressure, and atmosphere [18] [17]. |

| Computational Tools | Density Functional Theory (DFT) codes, Machine Learning Force Fields (e.g., OCP equiformer_V2) | Used for the initial calculation of descriptors (e.g., adsorption energies, d-band centers) and for running ML prediction models [34] [17]. |

SAPO-34, a silicoaluminophosphate zeotype with a chabazite (CHA) structure, has emerged as a superior catalyst for the methanol-to-olefins (MTO) process due to its unique combination of mild acidity, small pore openings (~3.8 Å), and exceptional shape selectivity toward light olefins (ethylene and propylene) [35] [36]. These properties enable high selectivity for light olefins, but also introduce a significant limitation: rapid catalyst deactivation due to coke formation within its microporous structure [36]. Overcoming this limitation requires optimizing complex synthesis parameters and reaction conditions, a multi-dimensional challenge perfectly suited for artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) approaches.

AI-driven methods have revolutionized catalyst development by establishing surrogate models that generalize hidden correlations between input variables and catalytic performance [37]. This data-driven paradigm accelerates the discovery of optimal catalytic systems while reducing the resource-intensive experimentation that has traditionally constrained materials science. This case study examines how AI and ML models are being deployed to predict and optimize SAPO-34 catalyst properties, validating these predictions against experimental data to guide the development of high-performance MTO catalysts.

AI and Machine Learning Methodologies in Catalyst Prediction

The application of AI in SAPO-34 development primarily utilizes three computational frameworks, each with distinct strengths. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) operate through multilayer feed-forward structures with back-propagation, capable of modeling highly non-linear relationships between synthesis parameters and catalytic outcomes [38]. Genetic Programming (GP) employs evolutionary algorithms to generate and select optimal model structures based on fitness criteria, often demonstrating superior prediction accuracy compared to other methods [39]. Ensemble ML Methods - including Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDT), and Extreme Gradient Boost (XGB) - combine multiple models to improve prediction robustness and generalization, particularly effective when working with complex, multi-source datasets [37].

Table 1: Comparison of AI Modeling Approaches for SAPO-34 Catalyst Prediction

| Model Type | Key Features | Reported Advantages | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANN with Bayesian Regulation | 3-10-3 layer structure; Bayesian training rule | Best fit for ultrasound parameter optimization; Superior to multiple linear regression [38] | Linking ultrasonic power, time, temperature to catalyst activity [38] |

| Genetic Programming (GP) | Evolutionary algorithm; symbolic regression | Highest accuracy for training and test data among intelligent methods [39] | Predicting effects of crystallization time, template amounts on selectivity [39] |

| NSGA-II-ANN Hybrid | Multi-objective genetic algorithm combined with ANN | Finds Pareto-optimal solutions for multiple competing objectives [38] | Maximizing methanol conversion, light olefins content, and catalyst lifetime simultaneously [38] |

| Ensemble ML with Bayesian Optimization | Random Forest, GBDT, XGB with Bayesian optimization | Efficient navigation of complex parameter spaces; High prediction accuracy for novel composites [37] | Discovering novel oxide-zeolite composites for syngas-to-olefin conversion [37] |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated machine learning and experimental validation workflow for catalyst development, adapted from research on oxide-zeolite composites [37]:

Experimental Validation of AI Predictions

Synthesis Protocols for SAPO-34 Catalysts

Ultrasound-Assisted Hydrothermal Synthesis

The ultrasound-assisted method enhances catalyst properties through controlled sonication. In validated protocols, the initial gel with molar composition 1Al₂O₃:1P₂O₅:0.6SiO₂:xCNT:yDEA:70H₂O is prepared using aluminum isopropoxide, tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS), and phosphoric acid as Al, Si, and P sources respectively [39]. Diethylamine (DEA) serves as the microporous template, while carbon nanotubes (CNT) act as mesopore-generating agents. The solution undergoes ultrasonic irradiation (typically 20 minutes at 243 W/m²) before crystallization, promoting uniformity and enhancing initial nucleation [39]. The crystallized product is then centrifuged, washed, dried (100°C for 12 hours), and calcined (550°C for 5 hours) to remove organic templates.

Green Synthesis Using Bio-Templates

Sustainable approaches utilize bio-derived templates to create hierarchical structures. In the dual-template method, okra mucilage (10% by volume) serves as a hard template due to its polysaccharide-rich, gel-like structure, while brewed coffee (10% by volume) acts as a soft template, providing small organic molecules that guide mesopore development [36]. The gel undergoes hydrothermal treatment at 180°C for 18 hours, facilitating stepwise formation of SAPO-34 particles through nucleation, crystallization, and nanoparticle aggregation [36]. This method aligns with green chemistry principles while creating beneficial hierarchical porosity.

Polyurea-Templated Hierarchical Synthesis

The CO₂-based polyurea approach introduces mesoporosity through a copolymer containing amine groups, ether segments, and carbonyl units that strongly interact with zeolite precursors [35]. Using a gel composition of 1.0 Al₂O₃:1.0 P₂O₅:4.0 TEA:0.4 SiO₂:100 H₂O:x PUa (where x=0-0.10), the polyurea inserts into the developing framework, creating defects and voids during crystallization [35]. Thermogravimetric analysis confirms appropriate calcination at 600°C for 400 minutes to completely remove both microporous and mesoporous templates.

Catalyst Performance Evaluation Methods

Catalytic performance is typically evaluated in fixed-bed or fluidized-bed reactors under controlled conditions. The standard MTO reaction protocol involves loading catalyst particles (250-500 μm diameter) in a reactor maintained at 400-480°C, with methanol fed at weight hourly space velocities (WHSV) of 2-10 gMeOH/gcat·h [40] [41]. Product streams are analyzed using online gas chromatography to determine methanol conversion and product selectivity. Catalyst lifetime is measured as time until methanol conversion drops below a threshold (typically 90-95%), while selectivity is calculated based on hydrocarbon product distribution at comparable conversion levels [39] [41].

Performance Comparison: AI-Optimized vs Conventional Catalysts

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data for SAPO-34 Catalysts Prepared by Different Methods

| Catalyst Type | Methanol Conversion (%) | Light Olefins Selectivity (%) | Catalyst Lifetime (min) | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional SAPO-34 | ~100 (initial) | 80-85 [36] | 210 [36] | Micropores only, moderate acidity |

| Ultrasound-Assisted (AI-optimized) | Improved with US power, time, temperature [38] | Significantly higher [39] | >210 [39] | High crystallinity, narrow particle distribution [39] |

| Hierarchical (Polyurea) | Maintained high conversion | Improved selectivity [35] | >2x conventional [35] | Micro-mesoporous structure, heterogeneous mesopores [35] |

| Green Bio-Template (Dual) | ~100 (initial) | 89.8 (at 240 min) [36] | Significantly extended [36] | Hierarchical micro-meso, smaller crystallites, moderated acidity [36] |

| CNT Hierarchical | High conversion | Enhanced light olefins [39] | Greatly improved [39] | Increased external surface, hierarchical structure [39] |

Catalyst Deactivation Behavior

The deactivation profiles of SAPO-34 catalysts vary significantly between reactor configurations and catalyst architectures. In fixed-bed reactors, catalyst deactivation follows a "cigar-burn" pattern, progressing sequentially through the bed and creating distinct zones of deactivation, methanol conversion, and olefin conversion [41]. In contrast, fluidized-bed reactors maintain spatially uniform coke distribution, with deactivation evolving uniformly with time-on-stream [41]. Hierarchical catalysts demonstrate superior resistance to deactivation, with the polyurea-templated SAPO-34 exhibiting more than twice the catalytic lifespan of conventional counterparts due to improved mass transport that reduces coke accumulation [35].

Research Reagent Solutions for SAPO-34 Synthesis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SAPO-34 Synthesis and Optimization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Aluminum Sources | Aluminum iso-propoxide (AIP) [39] [36] | Provides aluminum for framework formation |

| Silicon Sources | Tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS) [39] [36] | Silicon source for framework incorporation |

| Phosphorus Sources | Phosphoric acid (85%) [39] [36] | Provides phosphorus for framework formation |

| Microporous Templates | Tetraethylammonium hydroxide (TEAOH) [35] [36], Diethylamine (DEA) [39], Morpholine [36] | Structure-directing agents for CHA framework formation |

| Mesoporous Templates | Carbon nanotubes (CNT) [39], CO₂-based polyurea [35], Okra mucilage [36] | Create hierarchical mesoporous structures |

| Green Templates | Okra mucilage [36], Brewed coffee [36] | Eco-friendly alternatives for mesopore generation |

| Ultrasound-Assist Agents | - | Application of ultrasonic energy for enhanced nucleation [39] |

This case study demonstrates that AI-driven prediction models consistently identify SAPO-34 synthesis parameters that enhance catalytic performance beyond conventional formulations. The experimental validation confirms that AI-optimized catalysts—particularly those with hierarchical architectures achieved through ultrasound-assisted synthesis, polyurea templating, or green bio-templates—deliver superior light olefin selectivity and significantly extended catalyst lifetimes in MTO processes. The integration of machine learning with experimental catalysis creates a powerful feedback loop that accelerates catalyst development while providing fundamental insights into structure-performance relationships. As AI methodologies continue evolving and dataset sizes expand, these data-driven approaches promise to further revolutionize catalyst design, enabling more efficient and sustainable chemical processes.

Navigating Challenges: Data, Generalizability, and Interpretability in Catalytic ML

The integration of machine learning (ML) into catalyst discovery represents a paradigm shift from traditional trial-and-error experimentation to a data-driven discipline [14]. However, this transition faces a significant impediment: the data hurdle. The performance of ML models in catalysis is highly dependent on the quality, quantity, and standardization of training data [14]. Current catalytic datasets often suffer from incompleteness, heterogeneity, and high noise levels, creating bottlenecks that limit model accuracy and generalizability. This guide examines the core data challenges in machine learning for catalysis and systematically compares emerging computational and experimental strategies for overcoming these limitations, with a specific focus on validating predictions for catalytic performance in energy and chemical applications.

The Data Trilemma: Quality, Quantity, and Standardization

The fundamental challenge in catalytic ML resides in a trilemma between three interdependent data dimensions, each presenting distinct obstacles for researchers.

Data Quality Challenges: ML model performance is critically dependent on the quality of input data. Issues such as inconsistent experimental measurements, computational errors in density functional theory (DFT) calculations, and incomplete characterization of catalytic surfaces introduce noise that undermines model reliability [14]. The problem is particularly acute for complex catalytic systems where multiple facets, binding sites, and reaction pathways contribute to overall activity.

Data Quantity Limitations: Experimentally generating comprehensive catalytic datasets remains slow and expensive. While high-throughput experimental methods have accelerated data generation, they still cannot practically explore the vast combinatorial space of potential catalyst compositions and structures [14]. This data scarcity problem is especially pronounced for emerging catalytic reactions where limited prior knowledge exists.

Standardization Deficits: The absence of unified data standards across research groups impedes data aggregation and reuse. Variations in experimental protocols, reporting formats, and descriptor calculations create interoperability barriers that fragment the available data landscape [14]. Without standardized protocols for data collection and reporting, the catalytic community cannot effectively leverage collective data generation efforts.

Computational Solutions: Benchmarking Frameworks and Novel Descriptors

Simulation-Based Benchmarking with SimCalibration

For data-limited scenarios common in catalytic research, the SimCalibration meta-simulation framework provides a methodology for robust ML model selection [42]. This approach uses structural learners to infer data-generating processes from limited observational data, enabling generation of synthetic datasets for large-scale benchmarking.

Table 1: SimCalibration Framework Components and Functions

| Component | Function | Catalytic Application |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Learners (SLs) | Infer directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) from observational data | Map relationships between catalyst descriptors and activity |